Abstract

Polycystic kidney (PKD) and liver (PLD) diseases cause significant morbidity and mortality. A large body of evidence indicates that cyclic AMP plays an important role in their pathogenesis. Clinical trials of drugs that reduce cyclic AMP levels in target tissues are now in progress. Secretin may contribute to adenylyl cyclase-dependent urinary concentration and is a major agonist of adenylyl cyclase in cholangiocytes. To investigate the role of secretin in PKD and PLD, we have studied the expression of secretin and the secretin receptor in rodent models orthologous to autosomal recessive (PCK rat) and dominant (Pkd2−/WS25 mouse) PKD; the effects of exogenous secretin administration to PCK rats, PCK rats lacking circulating vasopressin (PCKdi/di), and Pkd2−/WS25 mice; and the impact of a nonfunctional secretin receptor on disease development in Pkd2−/WS25:SCTR−/− double mutants. Renal and hepatic secretin and secretin receptor mRNA and plasma secretin were increased in both models, and secretin receptor protein was increased in the kidneys and liver of Pkd2−/WS25 mice. However, exogenous secretin administered subcutaneously via osmotic pumps had minimal or negligible effects and the absence of a functional secretin receptor had no influence on the severity of PKD or PLD. Therefore, it is unlikely that by itself secretin plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of PKD and/or PLD.

Keywords: polycystic kidney disease, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, secretin, secretin receptor, cyclic AMP, vasopressin

autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) are important causes of end-stage renal disease in children and in adults (1, 17, 36). Both are systemic diseases. Hepatic involvement (cystic disease in ADPKD and hepatic fibrosis in ARPKD) causes significant morbidity and mortality. There is no proven effective therapy for these diseases, but recently identified molecular mechanisms have been successfully targeted in preclinical studies. Treatments targeting hormonal receptors that control cAMP in a cell/tissue-specific manner are attractive because of relative safety and tolerability. Clinical trials of vasopressin V2 receptor (V2R) antagonists (19, 37) and of long-acting somatostatin analogs (21, 33, 39) are ongoing.

V2R antagonists have no effect on polycystic liver disease or hepatic fibrosis because V2 receptors are not expressed in the liver (13, 38). While vasopressin is a major agonist of adenylyl cyclase in the renal collecting ducts, secretin is a major agonist of adenylyl cyclase in cholangiocytes (2, 22, 26, 30). In addition, secretin may contribute to adenylyl cyclase-dependent urinary concentration and could promote renal cyst formation along with vasopressin (6, 9, 10). Therefore, inhibition of secretin action on the kidney and the liver could be protective in polycystic kidney and liver disease. The studies presented here were designed to examine this hypothesis and determine whether development of secretin receptor (SCTR) blockers would be valuable to treat polycystic kidney and liver disease.

METHODS

Experimental Animals

Colonies of Pkd2+/− and Pkd2WS25/WS25 mice on a C57/B6 background and of PCK rats on a Sprague-Dawley background were maintained in the Animal Facilities of the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Brattleboro rats were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). The F1 offspring of PCK Brattleboro crosses was intercrossed to generate PCKdi/di homozygous double mutants. The generation of SCTR-null (SCTR−/−) mice has been previously described (10). A breeding strategy was designed to generate SCTR+/+:Pkd2−/WS25 and SCTR−/−:Pkd2−/WS25 mice. The experimental protocols were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee.

Genotyping

Tissue samples for genotyping were collected by tail clipping at 2 wk of age into labeled microfuge tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from rat tail using QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen Valencia, CA).

PCKdi/di and PCK+/+ rats.

In PCK rats, the Pkhd1 exon 36 is skipped and genomic sequencing shows that the mutation is an A (labeled with VIC) →T [labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)] transversion at −2 position of IVS35. In Brattleboro rats, there is a single nucleotide deletion (G, labeled with VIC, and N labeled with FAM) in exon B of the vasopressin gene. Genotyping for a single nucleotide polymorphism in Pkhd1 gene and a single base deletion in vasopressin gene was performed using commercially available Premade TaqMan genotyping assays. Real-time TaqMan PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's standard PCR. Briefly, 10 ng total DNA were mixed with the 2× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix to a final volume of 10 μl. Each sample underwent 45 amplification cycles on an ABI thermocycler. Two fluorescent labeled TaqMan probes were used for each locus using the dyes FAM (excitation, 494 nm) and VIC (excitation, 538 nm), which are easily differentiated in the Applied Biosystems Prism 7900HT PCR system. The resulting cluster plot showed strong fluorescent signals for each allele and clear separation between the three clusters, easily discriminating homozygous and heterozygous genotypes.

SCTR+/+:Pkd2−/WS25 and SCTR−/−:Pkd2−/WS25 mice.

Pkd2+/− mice and Pkd2WS25/WS25 mice were crossed to generate double heterozygote Pkd2−/WS25 mice. The WS25 mutation is due to the integration of an exon 1 disrupted by the introduction of a selectable neocassette into the first intron of Pkd2 without replacing the wild-type exon 1. This causes an increased rate of somatic Pkd2 mutations (intragenic homologous recombinations between tandemly repeated portions of the wild-type and mutant exon 1). Genomic DNA was digested with ApaI and analyzed by Southern blot with DNA probes for exon 2 (wild-type locus, 10 kb; mutant locus, 12 kb) and exon 1 (a doublet at 12–12.5 kb indicating 2 copies of exon 1 is unique to the WS25 allele). SCTR−/− mice were generated by replacing exon 10 of the gene with a PGK-1 promoter-neomycin resistance gene cassette (10). This results in a nonfunctional receptor. Genotyping was performed by PCR (primers: jpxb, 5′-CCATGGCTCAGGCAAGCC-3′; neoF1, 5′-GCTACTTCCATTTGTCACGTCCTG-43′; and jpxh, 5′-GCCTGAGGTTTCATACTCAGGCCC-3′).

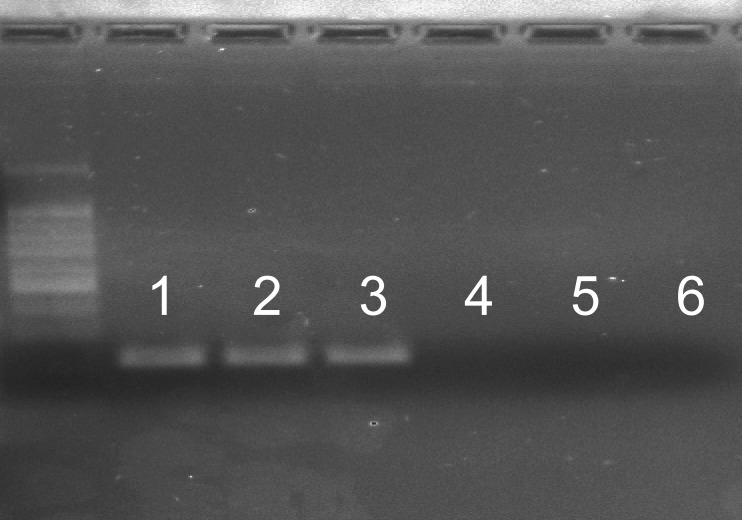

Confirmation of SCTR Transcripts with Deleted Exon 10

Total RNA was extracted from kidneys using an RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA synthesis was then performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A 1-μl aliquot of the RT reaction mixture was added directly to separate PCR mixtures. Each PCR mixture contained 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM (each) primer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 1.5 U of DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The primers were designed to span exon 10 to confirm its deletion: forward, primer 5′- CCATCTGGTGGGTCATTC-3′ in exon 9; and reverse, primer 5′- TCTGGGGAGAAGGCGAAG-3′ in exon 11. Amplification was performed with the following protocol: activation of the DNA polymerase at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s; final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were held at 4°C until analyzed. PCR products were confirmed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining under ultraviolet light.

Experimental Protocol

PCK rats were killed at 9–10 and Pkd2−/WS25 mice at 16 wk of age. 1-Deamino-8-d-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) and/or secretin were administered subcutaneously via osmotic minipumps starting at 3 wk of age. Dosing of the drugs, pump models and replacement schedules of the osmotic minipumps are described in results. During the course of the studies, the animals were placed in metabolic cages every 2–4 wk to measure urine output. At death, the animals were weighed and anesthetized with 60 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg ip xylazine. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture for determination of plasma urea and electrolyte levels. The right kidney and part of the liver were placed into preweighed vials containing 10% formaldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). These tissues were embedded in paraffin for histological studies. The left kidney and part of the liver were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for determination of cAMP and RNA and protein studies.

Histomorphometric Analysis

Four micrometers of transverse paraffin-embedded tissue sections of the kidney, including cortex, medulla, and papilla, and of the liver were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and used to measure cyst volumes. Renal and hepatic fibrosis was scored using the picrosirius red staining of collagen fibers. Image analysis procedures were performed with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). The MetaMorph software system includes a light microscope with a color digital camera (Nikon DXM 1200) and a Pentium IBM-compatible computer (Dell OptiPlex). The stained section was visualized under a Nikon microscope, and digital images were acquired using a high-resolution Nikon Digital camera and displayed on the monitor. The observer interactively applies techniques of enhancement for a better definition of interested structures and to exclude fields too damaged to be analyzed. A colored threshold is applied at a level that separate cysts from noncystic tissue and picrosirius red-positive material from background to calculate the volumes of renal and hepatic cysts or fibrosis. The areas of interest were expressed as a percentage of total tissue. All the histomorphometric analyses were performed blindly, without knowledge of group assignment.

Plasma Secretin Levels

Secretin levels were measured by enzyme immunoassay using a commercially available enzyme immunoassay rat and mouse secretin kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals) following the procedures recommended by the supplier. Briefly, 50 μl of a standard or a sample, 25 μl primary antiserum, and 25 μl biotinylated secretin were added to wells of 96-well immunoplates. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 h followed by five times of washing (300 μl/well) using assay buffer. Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase solution was then added (100 μl/well) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h, followed by six times of washing. Substrate solution (100 μl/well) was then added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, the reaction was terminated by addition 100 μl of 2 N HCl to each well. Optical density readings were obtained at 450 nm, and the amounts of secretin present were calculated.

Secretin and SCTR mRNAs

Total RNA was extracted from kidneys using an RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA synthesis was then performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Accumulation of PCR products was measured in real-time by using SYBR Green ER qPCR Supermix Universal kit (Invitrogen). Reaction was performed in ABI7900 (Applied Biosystems), starting with 10 min of preincubation at 95°C followed by 45 amplification cycles as follows: 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s. Primers used were as follows: rat secretin forward primer, 5′-ACTCAGGCCCTACAGGATTGGCTT-3′ and reverse primer, 5′- TCATCTGGGCTGCCTGGTTGTTTC-3′; mouse secretin forward primer ,5′- TCAGACGGAATGTTCACCAGCGAG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′- GGCTGTTCTCTGGGATATTTTCTG-3′; rat SCTR forward primer, 5′- AAGTGCAGTGTCCGAAGTTCCTCC-3′ and reverse primer, 5′- AAGGAGTTGTTTATGTTGACCCCA-3′; and mouse SCTR forward primer, 5′- TTTGTGCTCTTCGGATGGGGTTCT-3′ and reverse primer, 5′- TGGACAGAATCACAGGCCCTCGAA-3′. 18S was used as housekeeping gene for arbitrary unit calculation for every tested gene. Product identity was confirmed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining under ultraviolet light.

SCTR Protein

SCTR protein was measured by Western blot analysis using anti-SCTR antibody (Lifespan Biosciences). Kidneys were lysed in a RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined with BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Chemical). Kidney lysate were heated in a sample buffer, electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to PVDF membrane. The blots were blocked with 5% milk in TBS-T (0.1% Tween-20) at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C. After incubation, the membrane were washed and incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was performed using enhanced ECL (Pierce Chemical).

Renal cAMP Content

The kidneys were ground to fine powder under liquid nitrogen in a stainless steel mortar and homogenized in 10 vol of cold 5% TCA in a glass-Teflon tissue grinder. After centrifugation at 600 g for 10 min, the supernatants were extracted with 3 vol of water-saturated ether. After the aqueous extracts were dried, the reconstituted samples were processed without acetylation using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO). The results were expressed in picomoles per milligrams of protein.

Chemical Determinations

Plasma urea and electrolytes were measured with a Hitachi 977 analyzer.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons between the groups were performed by ANOVA. Since gender may have an effect on the development of polycystic kidney disease, a two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the main effect of gender and treatments and their interaction.

RESULTS

Tissue Secretin mRNA and Plasma Secretin

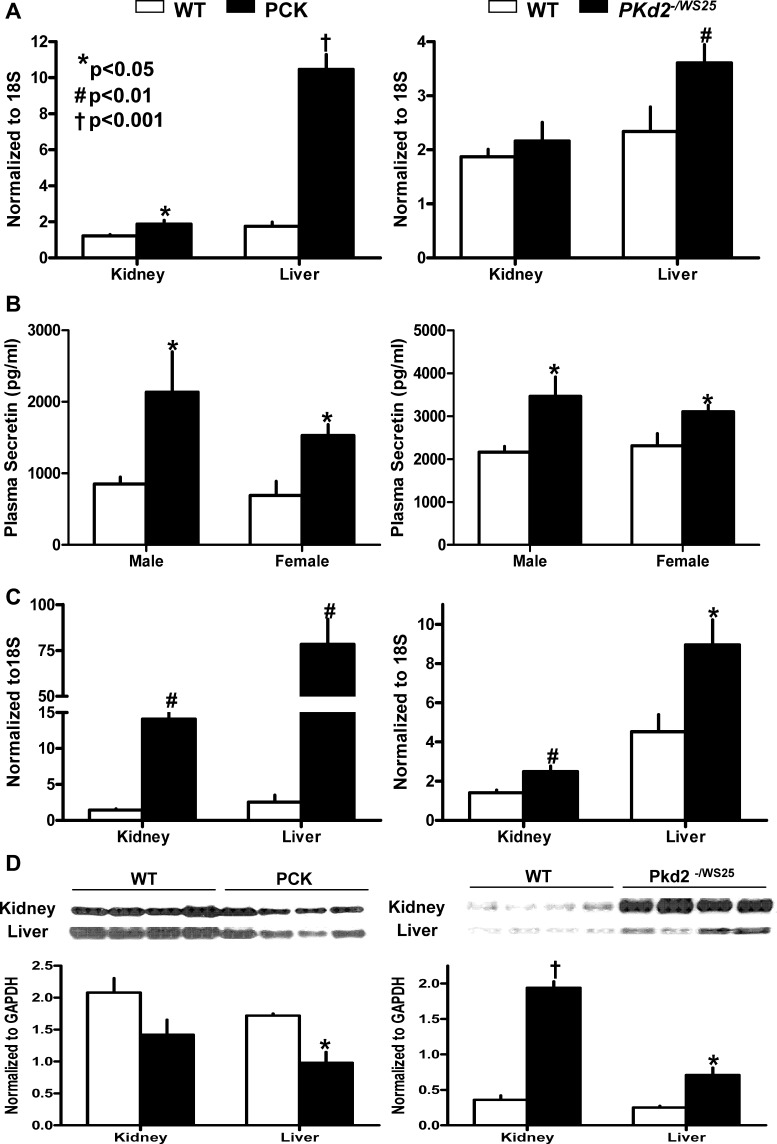

The expression of secretin mRNA is increased fivefold, compared with wild-type controls, in the liver of PCK rats and to a lesser extent in the kidney of PCK rats and in the liver of Pkd2−/WS25 mice (Fig. 1A). PCR products were confirmed by sequencing. Plasma secretin levels were also higher in PCK rats and Pkd2−/WS25 mice compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A: secretin mRNA expression in the kidneys and livers of PCK rats, Pkd2WS25/− mice, and wild-type (WT) rats and mice (n = 6 per group). B: plasma secretin levels in male and female and PCK rats and in Pkd2WS25/− mice, and wild-type rats and mice (n = 6 per group). C: secretin receptor mRNA expression in the kidneys and livers of male PCK rats, Pkd2WS25/− mice, and wild-type rats and mice (n = 6 per group). D: secretin receptor immunoblots in kidney and liver homogenates from male PCK rats, Pkd2WS25/− mice, and wild-type rats and mice (n = 4 per group). Columns represent means ± SD.

Tissue SCTR mRNA and Protein

The expression of SCTR mRNA was increased in the livers and kidneys of PCK rats and Pkd2−/WS25 mice compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1C). PCR products were confirmed by sequencing. Immunoblotting with an anti-mouse SCTR antibody showed markedly increased expression of the SCTR protein was in the kidneys and livers of Pkd2−/WS25 mice but not in those of PCK rats, compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1D). We found this antibody not adequate for immunohistochemical localization.

Administration of Secretin in PCK Rats

Secretin was administered subcutaneously (10 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) from 3 to 10 wk of age via an Alzet Osmotic pump model 2002 placed at 3 wk of age and replaced 2 and 5 wk later with an Alzet osmotic pump model 2ML4. At death, concentrations of secretin in plasma and cAMP in renal tissue were significantly higher than those in animals receiving vehicle alone (Table 1). The administration of secretin was accompanied by higher kidney weights, cyst and fibrosis scores, and plasma urea concentrations compared with those receiving vehicle. Nevertheless, these effects were of lesser magnitude than those previously reported with administration of DDAVP. To determine whether a higher dose of secretin would have more marked effects, secretin (200 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) was administered subcutaneously from 3 to 9 wk of age via an Alzet osmotic pump model 2002 replaced every 2 wk. At death, concentrations of secretin in plasma were significantly higher than those in animals receiving vehicle (Table 2). This was accompanied by a slight but significant increase in kidney weight, but no effects on renal cAMP, cyst, or fibrosis scores. Neither dose of secretin had a detectable effect on liver weight or on hepatic cyst and fibrosis scores.

Table 1.

Effect of subcutaneous secretin administration (10 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) on the development of polycystic kidney and liver disease in PCK rats

| Male |

Female |

P Value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 6) | SCT (n = 6) | Control (n = 6) | SCT (n = 6) | SCT | Gender | |

| Body wt, g | 422.3 ± 12.5 | 420.0 ± 17.8 | 261.5 ± 10.8 | 267.8 ± 8.2 | NS | <0.0001 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 1.44 ± 0.22 | 1.74 ± 0.24 | 1.20 ± 0.21 | 1.52 ± 0.28 | 0.0047 | 0.0287 |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 19.8 ± 5.4 | 31.8 ± 4.8 | 14.3 ± 8.1 | 24.5 ± 5.0 | 0.0002 | 0.0170 |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 2.44 ± 0.93 | 5.82 ± 1.20 | 3.05 ± 1.23 | 5.24 ± 2.71 | 0.0006 | NS |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 18.7 ± 7.0 | 23.3 ± 4.4 | 13.6 ± 4.7 | 18.2 ± 3.3 | 0.0362 | 0.0222 |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 0.85 ± 0.24 | 2.10 ± 1.05 | 0.69 ± 0.48 | 1.53 ± 0.37 | 0.0005 | NS |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 32.8 ± 2.6 | 37.1 ± 7.2 | 29.3 ± 1.8 | 33.2 ± 2.2 | NS | 0.0382 |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 15.3 ± 1.9 | 15.4 ± 4.4 | 6.60 ± 2.10 | 9.70 ± 2.50 | NS | <0.0001 |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 5.29 ± 0.13 | 5.13 ± 0.26 | 5.59 ± 0.24 | 5.62 ± 0.25 | NS | 0.0004 |

| Liver cyst score, % | 3.74 ± 0.88 | 4.06 ± 0.48 | 4.28 ± 0.82 | 4.47 ± 1.10 | NS | NS |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 4.76 ± 1.23 | 7.36 ± 1.67 | 6.11 ± 1.46 | 7.71 ± 2.18 | 0.0060 | NS |

Values are means ± SD.

SCT, secretin; NS, nonsignificant.

Table 2.

Effect of subcutaneous secretin administration (200 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) on the development of polycystic kidney and liver disease in PCK rats

| Male |

Female |

P Value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 4) | SCT (n = 5) | Control (n = 6) | SCT (n = 6) | SCT | Gender | |

| Body wt, g | 370.2 ± 30.9 | 359.0 ± 31.8 | 246.9 ± 25.4 | 244.8 ± 21.0 | NS | <0.0001 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 1.10 ± 0.17 | 1.25 ± 0.14 | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 1.21 ± 0.13 | 0.0269 | NS |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 18.3 ± 10.2 | 17.7 ± 5.28 | 17.8 ± 6.5 | 17.4 ± 6.1 | NS | NS |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 2.23 ± 1.86 | 3.42 ± 2.85 | 4.31 ± 4.04 | 3.34 ± 3.02 | NS | NS |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 11.7 ± 2.5 | 16.5 ± 6.2 | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 10.6 ± 1.9 | NS | NS |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 2.00 ± 1.43 | 4.09 ± 1.86 | 1.40 ± 0.51 | 2.90 ± 0.60 | 0.0025 | NS |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 46.3 ± 26.4 | 56.7 ± 31.6 | 50.4 ± 26.9 | 51.5 ± 31.2 | NS | NS |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 15.5 ± 4.1 | 17.7 ± 7.8 | 9.78 ± 2.8 | 11.5 ± 2.4 | NS | NS |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 4.66 ± 0.57 | 4.63 ± 0.61 | 5.42 ± 0.73 | 5.21 ± 0.80 | NS | 0.0074 |

| Liver cyst score, % | 4.65 ± 1.79 | 4.94 ± 2.21 | 4.97 ± 1.46 | 4.90 ± 1.48 | NS | NS |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 6.76 ± 1.68 | 6.53 ± 2.05 | 6.67 ± 2.44 | 5.49 ± 2.21 | NS | NS |

Values are means ± SD.

Administration of Secretin to PCKdi/di Rats

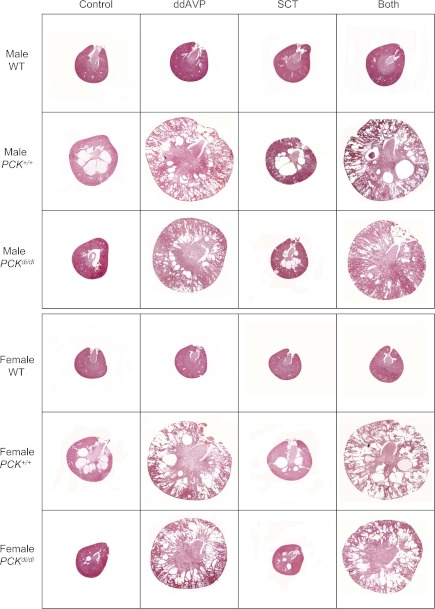

The constant presence of vasopressin in the circulation and its tonic action on the kidney could account for the inability to demonstrate a more pronounced effect of secretin on renal cystogenesis in the PCK rat, since vasopressin is more powerful than secretin as an agonist of cAMP generation in the collecting duct. Therefore, we studied the effect of secretin alone, vasopressin V2 receptor agonist DDAVP alone, and both combined on the development of cystic disease in PCK/Brattleboro double mutant rats (PCKdi/di) that lack circulating vasopressin, as well as in PCK rats with intact vasopressin (PCK+/+) and in wild-type Sprague-Dawley rats. In wild-type rats, DDAVP caused a small but significant increase in kidney weight, significant reductions in urine volume and plasma sodium, and an increase in plasma urea. None of these parameters was affected by secretin alone, and the effects of DDAVP and secretin combined were not different from those with DDAVP alone (results not shown). In PCK+/+ rats, DDAVP caused a significant increase in renal cAMP, which was accompanied by marked increases in kidney, renal cyst and fibrosis volumes and plasma urea concentrations, whereas the effects on urine volume and plasma sodium were not significant (Table 3; Fig. 2). Secretin alone had no significant effects and the effects of DDAVP and secretin combined were not different from those of DDAVP alone. In PCKdi/di, the administration of DDAVP increased renal cAMP, corrected the polyuria, lowered the plasma sodium, and rescued the cystic phenotype as reflected by marked increases in kidney weights, cyst and fibrosis scores, and plasma urea levels (Table 4; Fig. 2). Secretin alone had no significant effects and the effects of DDAVP and secretin combined were not different from those of DDAVP alone.

Table 3.

Effect of subcutaneous DDAVP (10 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) and/or secretin (20 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) administration on the development of polycystic kidney and liver disease in PCK+/+ rats

| Control (n = 8) | DDAVP (n = 8) | SCT (n = 8) | Both (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||

| Body wt, g | 408.8 ± 41.9 | 354.9 ± 23.9 | 384.6 ± 42.2 | 359.1 ± 22.7 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 1.46 ± 0.29 | 6.94 ± 3.23 | 1.42 ± 0.18 | 7.73 ± 2.62 |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 19.8 ± 11.3 | 42.6 ± 12.1 | 18.9 ± 8.3 | 43.0 ± 4.4 |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 0.70 ± 0.61 | 6.79 ± 3.57 | 0.97 ± 0.70 | 8.45 ± 10.32 |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 15.2 ± 3.7 | 29.9 ± 26.3 | 10.5 ± 1.2 | 18.5 ± 6.2 |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 0.35 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.56 ± 0.08 |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 34.9 ± 7.7 | 107.2 ± 28.6 | 40.9 ± 8.6 | 129.8 ± 25.7 |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 16.1 ± 9.7 | 13.5 ± 4.2 | 15.8 ± 6.1 | 18.1 ± 7.7 |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 5.19 ± 0.60 | 5.79 ± 0.26 | 7.07 ± 4.77 | 5.48 ± 0.59 |

| Liver cyst score, % | 3.49 ± 1.05 | 5.01 ± 2.29 | 12.3 ± 19.6 | 4.78 ± 2.44 |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 5.06 ± 1.97 | 5.80 ± 2.59 | 7.05 ± 7.05 | 4.3 ± 2.24 |

| Female | ||||

| Body wt, g | 269.0 ± 6.4 | 263.6 ± 19.2 | 259.8 ± 17.8 | 255.1 ± 19.7 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 1.42 ± 0.35 | 7.73 ± 5.89 | 1.30 ± 0.33 | 7.10 ± 1.91 |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 18.8 ± 4.4 | 46.6 ± 14.9 | 10.8 ± 4.6 | 39.4 ± 7.8 |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 1.25 ± 0.64 | 8.16 ± 9.17 | 0.76 ± 0.62 | 8.68 ± 9.55 |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 13.8 ± 3.9 | 28.5 ± 8.1 | 14.2 ± 3.5 | 28.1 ± 10.6 |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 0.53 ± 0.17 | 0.52 ± 0.21 | 0.66 ± 0.18 | 0.64 ± 0.16 |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 42.1 ± 2.6 | 107.9 ± 35.9 | 37.7 ± 4.9 | 102.6 ± 20.1 |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 10.1 ± 5.5 | 10.5 ± 4.3 | 11.1 ± 4.6 | 10.3 ± 2.2 |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 6.37 ± 0.96 | 6.66 ± 0.69 | 6.79 ± 2.17 | 5.97 ± 0.45 |

| Liver cyst score, % | 6.97 ± 3.23 | 7.07 ± 3.79 | 6.25 ± 2.67 | 5.16 ± 1.32 |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 6.88 ± 4.02 | 6.01 ± 2.70 | 6.92 ± 4.40 | 5.52 ± 2.01 |

| P Values | ||||

| DDAVP | SCT | Both | Gender | |

| Body wt | 0.0034 | NS | 0.0018 | <0.0001 |

| Kidney wt | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Kidney cyst score | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Kidney fibrosis score | 0.0065 | NS | 0.0050 | NS |

| Renal cAMP | 0.0079 | NS | 0.0012 | NS |

| Plasma SCT | NS | NS | 0.0065 | 0.0043 |

| Plasma urea | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| 24-h Urine | NS | NS | NS | 0.0006 |

| Liver wt | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Liver cyst score | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Liver fibrosis score | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Values are means ± SD.

DDVAP, 1-deamino-8-d-arginine vasopressin.

Fig. 2.

Cross-sections of kidneys stained with hematoxylin-eosin from male and female wild-type, PCK+/+ and PCKdi/di rats treated with vehicle, 1-Deamino-8-d-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP; 10 ng·100 g−1·h−1), secretin (20 ng·100 g−1·h−1), or both via osmotic minipumps.

Table 4.

Effect of subcutaneous DDAVP (10 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) and/or secretin (20 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) administration on the development of polycystic kidney and liver disease in PCKdi/di rats

| Control (n = 6) | DDAVP (n = 6) | SCT (n = 6) | Both (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||

| Body wt, g | 330.0 ± 37.9 | 357.2 ± 31.2 | 367.2 ± 25.6 | 356.0 ± 33.7 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 5.09 ± 1.60 | 1.11 ± 0.13 | 4.99 ± 1.91 |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 3.99 ± 3.61 | 29.6 ± 8.8 | 10.2 ± 8.3 | 31.9 ± 9.3 |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 1.52 ± 1.53 | 4.24 ± 4.85 | 1.47 ± 1.45 | 4.15 ± 4.28 |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 7.73 ± 2.67 | 32.7 ± 9.8 | 11.2 ± 5.5 | 21.7 ± 4.9 |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 0.42 ± 0.16 | 0.65 ± 0.25 | 0.90 ± 0.24 | 0.92 ± 0.48 |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 39.9 ± 11.2 | 131.3 ± 38.2 | 38.3 ± 7.24 | 113.0 ± 30.8 |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 70.8 ± 15.3 | 16.9 ± 7.5 | 82.9 ± 23.4 | 16.1 ± 5.3 |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 5.31 ± 0.63 | 6.27 ± 1.48 | 6.49 ± 1.83 | 7.36 ± 4.24 |

| Liver cyst score, % | 9.36 ± 4.47 | 8.40 ± 1.79 | 7.73 ± 2.87 | 9.80 ± 7.73 |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 10.1 ± 6.9 | 9.93 ± 5.10 | 8.82 ± 2.73 | 7.02 ± 3.49 |

| Control (n = 5) | DDAVP (n = 5) | SCT (n = 5) | Both (n = 4) | |

| Female | ||||

| Body wt, g | 234.8 ± 32.3 | 236.8 ± 19.5 | 226.2 ± 30.2 | 266.3 ± 34.0 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 1.06 ± 0.34 | 4.73 ± 1.58 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 4.54 ± 1.89 |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 8.45 ± 4.11 | 31.8 ± 7.16 | 10.0 ± 2.42 | 32.6 ± 12.9 |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 0.50 ± 0.50 | 5.82 ± 7.27 | 1.28 ± 0.91 | 3.38 ± 2.55 |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 7.84 ± 2.27 | 19.3 ± 2.9 | 11.1 ± 2.8 | 31.7 ± 28.1 |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 0.46 ± 0.15 | 0.43 ± 0.14 | 0.65 ± 0.18 | 0.56 ± 0.24 |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 40.0 ± 7.72 | 94.9 ± 23.8 | 48.4 ± 15.1 | 87.8 ± 26.2 |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 52.5 ± 21.5 | 12.6 ± 4.6 | 54.5 ± 33.4 | 12.8 ± 5.04 |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 6.45 ± 2.28 | 5.88 ± 1.05 | 8.03 ± 2.17 | 5.93 ± 0.92 |

| Liver cyst score, % | 8.23 ± 4.27 | 5.77 ± 1.84 | 8.21 ± 2.02 | 6.76 ± 1.90 |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 12.8 ± 6.1 | 6.58 ± 1.29 | 11.9 ± 4.8 | 6.07 ± 0.76 |

| P Values | ||||

| DDAVP | SCT | Both | Gender | |

| Body wt | NS | NS | NS | <0.0001 |

| Kidney wt | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Kidney cyst score | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Kidney fibrosis score | 0.0450 | NS | 0.0372 | NS |

| Renal cAMP | <0.0001 | NS | 0.0032 | NS |

| Plasma SCT | NS | 0.0006 | 0.0333 | 0.0040 |

| Plasma urea | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| 24-h Urine | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | 0.0146 |

| Liver wt | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Liver cyst score | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Liver fibrosis score | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Values are means ± SD.

Administration of Secretin in Pkd2−/WS25 Mice

Subcutaneous administration of secretin (20 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) from 4 to 16 wk of age via an Alzet osmotic pump model 1004 replaced every 4 wk had no effect on renal cAMP levels, kidney and liver weights, cyst and fibrosis scores, and plasma urea or sodium concentrations (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of subcutaneous secretin administration (20 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) on the development of polycystic kidney and liver disease in Pkd2−/WS25 mice

| Male |

Female |

Two-Way ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 11) | SCT (n = 11) | Control (n = 11) | SCT (n = 9) | SCT | Gender | |

| Body wt, g | 22.6 ± 2.2 | 22.0 ± 2.3 | 19.1 ± 1.3 | 19.4 ± 2.1 | NS | <0.0001 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 2.11 ± 0.66 | 1.98 ± 0.30 | 2.12 ± 0.64 | 2.02 ± 0.29 | NS | NS |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 19.2 ± 21.4 | 8.23 ± 7.08 | 18.6 ± 16.3 | 23.4 ± 15.5 | NS | NS |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 1.31 ± 1.54 | 0.91 ± 0.67 | 1.42 ± 1.72 | 1.06 ± 0.82 | NS | NS |

| Renal cAMP, pmol/mg protein | 5.93 ± 3.39 | 8.72 ± 3.36 | 6.78 ± 2.73 | 7.08 ± 4.12 | NS | NS |

| Plasma SCT, ng/ml | 1.33 ± 0.60 | 2.05 ± 1.38 | 1.16 ± 0.83 | 1.45 ± 0.93 | NS | NS |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 100.9 ± 27.9 | 89.2 ± 17.9 | 85.2 ± 23.9 | 91.8 ± 32.3 | NS | NS |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 1.82 ± 0.91 | 3.35 ± 2.16 | 1.59 ± 0.84 | 1.43 ± 0.83 | NS | 0.0131 |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 5.11 ± 0.36 | 5.14 ± 0.47 | 5.27 ± 0.43 | 5.46 ± 0.50 | NS | NS |

| Liver cyst score, % | 5.74 ± 5.53 | 2.69 ± 1.32 | 4.10 ± 1.94 | 5.30 ± 4.69 | NS | NS |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 1.19 ± 1.06 | 1.07 ± 0.81 | 0.70 ± 0.30 | 1.90 ± 2.27 | NS | NS |

Values are means ± SD.

Development on Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease in Pkd2−/WS25/SCTR−/− Mice

Since secretin is continuously present in the circulation and in the renal and hepatic tissues, the negligible effect of exogenous secretin on the development of cystic disease could have been due to the inability to achieve a sufficient increase in circulating or tissue levels of this hormone. Alternatively, secretin could exert an important, but just permissive, role on cystogenesis. To investigate whether disruption of the SCTR affects the development of polycystic kidney and/or liver disease, we crossed SCTR−/− and Pkd2 mutant mice to generate Pkd2−/WS25/SCTR−/− and Pkd2−/WS25/SCTR+/+ mice. SCTR−/− mice have been previously described and were generated by replacing exon 10 with a PGK-1 promoter-neomycin resistance gene cassette. Exon 10 encodes the third endoloop of the SCTR which is important for its cell surface presentation and maturation. Deletion of exon 10 was confirmed by RT-PCR in double mutants (Fig. 3). Kidney and liver weights, as well as cyst and fibrosis scores in both organs, were similar among the different groups (Table 6). Therefore, the lack of a secretin effect on the kidney or the liver does not protect against the development of polycystic kidney or liver disease.

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR amplification of secretin receptor (SCTR) mRNA from kidneys using primers spanning exon 10. Wild-type band (211 bp) was detected in WT (lane 1); Pkd2−/WS25:SCTR+/+ (lane 2) and Pkd2−/WS25:SCTR+/− (lane 3), but not in Pkd2−/WS25:SCTR−/− (lane 4), or SCTR−/− (lane 5) mouse kidney cDNA. Lane 6 is water control.

Table 6.

Polycystic kidney and liver disease in Pkd2−/WS25/SCTR+/+and Pkd2−/WS25/SCTR−/− mice

| Male |

Female |

Two-way ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCTR+/+ (n = 12) | SCTR−/− (n = 7) | SCTR+/+ (n = 9) | SCTR−/− (n = 15) | SCTR | Gender | |

| Body wt, g | 33.5 ± 3.1 | 34.0 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 1.7 | 25.5 ± 2.5 | NS | <0.0001 |

| Kidney wt, %body wt | 1.65 ± 0.21 | 1.58 ± 0.21 | 1.74 ± 0.55 | 1.47 ± 0.35 | NS | NS |

| Kidney cyst score, % | 15.5 ± 9.2 | 18.8 ± 10.0 | 20.5 ± 15.7 | 14.9 ± 12.4 | NS | NS |

| Kidney fibrosis score, % | 1.69 ± 1.06 | 2.08 ± 1.40 | 2.85 ± 3.30 | 2.97 ± 1.73 | NS | NS |

| Plasma urea, mg/dl | 62.0 ± 20.7 | 53.8 ± 11.8 | 57.1 ± 8.9 | 50.2 ± 10.4 | NS | NS |

| 24-h Urine, ml | 2.31 ± 0.87 | 2.29 ± 1.45 | 1.86 ± 0.63 | 2.62 ± 1.20 | NS | NS |

| Liver wt, %body wt | 5.31 ± 1.06 | 5.14 ± 0.72 | 5.43 ± 0.62 | 4.86 ± 0.60 | NS | NS |

| Liver cyst score, % | 5.83 ± 5.42 | 6.33 ± 7.06 | 4.17 ± 2.67 | 5.14 ± 2.39 | NS | NS |

| Liver fibrosis score, % | 0.87 ± 0.34 | 1.60 ± 1.76 | 1.02 ± 0.54 | 1.13 ± 0.60 | NS | NS |

Values are means ± SD.

DISCUSSION

There is significant agreement that cAMP plays an important role in the pathogenesis of polycystic kidney and liver disease (15, 35, 40). Clinical trials of drugs targeting hormonal receptors that control cAMP levels in cystic epithelia (vasopressin V2 antagonism and somatostatin analogs) are ongoing (19, 21, 33, 37, 39) after promising results in preclinical studies (13, 29, 38). The current study was designed to determine whether the administration of exogenous secretin, a hormone that stimulates the generation of cAMP in the distal nephron, collecting duct, and large (>15 μm in diameter) but not small bile ducts, or the knockout of the SCTR affect the development of polycystic kidney or polycystic liver disease in orthologous animal models (24, 42).

Secretin, a 27-amino acid peptide (molecular weight: 3055.5), is released by the duodenum in response to gastric acid and digested products of fat and protein (7, 11, 25). Plasma concentrations of secretin in humans, rats, and dogs are in the picomolar or low nanomolar range both at baseline and following maximal stimulation after a meal (8, 16, 23). Secretin acts on the SCTR, a G-protein-coupled receptor that signals through the activation of adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase A and is expressed in the gastric mucosa and smooth muscle, pancreatic ducts, and large bile ducts. Exogenous administration of secretin at rates 2.5–5 pmol·kg−1·h−1 achieves plasma concentrations comparable to those observed in the postprandial period (28). At physiological concentrations, secretin inhibits gastric acid secretion and motility and stimulates secretion of fluid and bicarbonate by pancreatic ductal epithelial cells and secretion of bicarbonate by cholangiocytes (20).

Secretin and its receptor are also expressed in extra-gastrointestinal organs including the kidney, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, and lung (7, 11, 25). In the kidney, the function of secretin and the location of the SCTR resemble those of vasopressin and the V2 receptor. The SCTR is mainly located in collecting ducts and thick ascending limbs of Henle (6, 10). Like AVP, secretin increases renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (18, 20). Microinjection of saline containing 1 nM secretin into the last convolution of the proximal tubule increased single nephron glomerular filtration rate from 25 ± 4 to 61 ± 8 nl/min, presumably through an effect on the macula densa and tubulo-glomerular feedback (32). At pharmacological doses, secretin stimulates adenylyl cyclase in outer medullary collecting ducts. Intravenous injection of pharmacologic doses of secretin activates adenylyl cyclase in the outer medulla and decreases the urine output in wild-type as well as in homozygous vasopressin-deficient Brattleboro rats (ED50 = 700 and ED25 = 120 nmol/kg body wt; Ref. 6). More recently, secretin (10 nM) has been shown to induce translocation of aquaporin-2 to the plasma membrane in isolated inner medullary rat collecting ducts, while the knockout of the SCTR downregulates the expression of aquaporin-2 and aquaporin-4, impairs the translocation of aquaporin-2 to the plasma membrane, and causes a moderate impairment in urinary concentration (1,897 ± 59 vs. 2,374 ± 57 mosmol/kgH2O) and polyuria (2.3 ± 0.1 vs. 1.7 ± 0.1 ml/24 h) compared with wild-type mice (10).

Based on the similarities between the actions of secretin and vasopressin on the kidney and our previous study (41) showing that vasopressin directly regulates cyst growth in PCK rats, we hypothesized that secretin would also have an effect on the development of PKD. In fact, secretin at pharmacological concentration (1 μM) has been shown to stimulate transepithelial fluid secretion by cyst derived cell monolayers and the proliferation of cultured kidney cells from patients with ADPKD (43). The results of the current study, however, do not support this hypothesis. While the administration of DDAVP markedly enhanced the development of PKD, administration of secretin at rates that increase blood levels within or above the physiological range had small (at 10 ng·h−1·100 g body wt−1) or negligible (at 200 ng/h/100 g body wt) effects in PCK rats. The small effect of secretin noted with the lower but not the higher dose may be consistent with its effect on exocytosis in isolated cholangiocytes that peaks at a concentration of 5 × 10−8 M and decreases at higher concentrations (22). Moreover, secretin failed to rescue the cystic phenotype in PCKdi/di rats that lack circulating vasopressin and the knockout of SCTR had no effect on the development of PKD in Pkd2−/WS25 mice. These results indicate that SCTR blockers are not likely to be an effective PKD treatment.

Secretin increases the content of cAMP and stimulates exocytosis in isolated rat cholangiocytes with half-maximal responses at 7 nmol/l (22). Administration of secretin into isolated perfused rat livers via the hepatic artery (that supplies blood to the bile ducts) increases biliary bicarbonate (but not bile flow) with a half-maximal response at 282 pmol/l (20). At pharmacological concentrations (100–200 nM), it stimulates fluid secretion in isolated bile duct units (2, 30). Secretin also increases bile flow in vivo in conditions associated with proliferation of large cholangiocytes, such as bile duct ligation, partial hepatectomy, feeding of bile acids, and administration of levels of carbon tetrachloride (3, 4, 27, 34). The cholangiocyte proliferative response in these animal models is associated with increased SCTR gene expression and elevated secretin-stimulated cAMP levels. Furthermore, administration of secretin (2.5 nmol·kg body wt−1·day−1) intraperitoneally by osmotic minipumps for 1 wk stimulates the proliferation of large cholangiocytes, while the knockout of the SCTR inhibits their proliferation following bile duct ligation by ∼50% (14).

Based on the role of secretin in cholangiocyte physiology and pathology, we hypothesized that secretin would have an effect on the development of polycystic liver disease. This hypothesis is supported by additional published observations. Intravenous administration of secretin increased the rate of fluid secretion in two of three percutaneously drained hepatic cysts while intracystic pressure was kept constant (12). The histamine H2 blocker cimetidine reduced the rate of surgical drainage following the fenestration of hepatic cysts, presumably by lowering gastric acid production and secretin secretion (31). The main transport proteins participating in bile secretion (i.e., the water channel aquaporin-1, the chloride channel cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, and the anion exchanger AE2) are overexpressed in livers from PCK rats, and 1 μM secretin stimulates the expansion of PCK liver cysts cultured between two layers of type I collagen (55). Our own results show that, as previously reported in other proliferative cholangiocyte disorders, SCTR is overexpressed in polycystic livers from PCK rats and Pkd2−/WS25 mice. Despite the evidence supporting the working hypothesis, we have not been able to demonstrate an aggravating effect of exogenous secretin or a protective effect from knocking out the SCTR on the development of polycystic liver disease. It is possible that failure to demonstrate small but statistically significant effects might have been due to the relatively small size of the groups. It is also possible that a higher pharmacological dose of secretin could have had an effect. Nevertheless, the lack of protection from the SCTR knockout indicates that SCTR blockers are not likely to be effective to treat polycystic liver disease.

In summary, the results of our study indicate that by itself secretin does not play a significant role in the pathogenesis of polycystic kidney and liver disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-44863, Mayo Translational PKD Center (DK-090728), and the PKD Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Adeva M, El-Youssef M, Rossetti S, Kamath PS, Kubly V, Consugar MB, Milliner DM, King BF, Torres VE, Harris PC. Clinical and molecular characterization defines a broadened spectrum of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Medicine (Baltimore) 85: 1–21, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alpini G, Glaser S, Robertson W, Rodgers RE, Phinizy JL, Lasater J, LeSage GD. Large but not small intrahepatic bile ducts are involved in secretin-regulated ductal bile secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 272: G1064–G1074, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alpini G, Glaser SS, Ueno Y, Rodgers R, Phinizy JL, Francis H, Baiocchi L, Holcomb LA, Galigiuri A, Lesage F. Bile acid feeling induces cholangiocyte proliferatio and secretion: evidence for bile acid-redulated ductal secretion. Gastroenterology 116: 179–186, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alpini G, Lenzi R, Sarkozi L, Tavoloni N. Biliary physiology in rats with bile ductular cell hyperplasia. Evidence for a secretory function of proliferated bile ductules. J Clin Invest 81: 569–578, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banales JM, Masyuk TV, Bogert PS, Huang BQ, Gradilone SA, Lee SO, Stroope AJ, Masyuk AI, Medina JF, LaRusso NF. Hepatic cystogenesis is associated with abnormal expression and location of ion transporters and water channels in an animal model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol 173: 1637–1646, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charlton CG, Quirion R, Handelmann GE, Miller RL, Jensen RT, Finkel MS, O'Donohue TL. Secretin receptors in the rat kidney: adenylate cyclase activation and renal effects. Peptides 7: 865–871, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chey WY, Chang TM. Secretin 100 years later. J Gastroenterol 38: 1025–1035, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chey WY, Lee YH, Hendricks JG, Rhodes RA, Tai HH. Plasma secretin concentrations in fasting and postprandial state in man. Am J Dig Dis 23: 981–988, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chu JY, Cheng CY, Lee VH, Chan YS, Chow BK. Secretin and body fluid homeostasis. Kidney Int 79: 280–287, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chu JY, Chung SC, Lam AK, Tam S, Chung SK, Chow BK. Phenotypes developed in secretin receptor-null mice indicated a role for secretin in regulating renal water reabsorption. Mol Cell Biol 27: 2499–2511, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chu JY, Yung WH, Chow BK. Secretin: a pleiotrophic hormone. Ann NY Acad Sci 1070: 27–50, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Everson G, Emmett M, Brown W, Redmond P, Thickman D. Functional similarities of hepatic cystic and biliary epithelium: studies of fluid constituents and in vivo secretion in response to secretin. Hepatology 11: 557–565, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gattone VH, Wang X, Harris PC, Torres VE. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med 9: 1323–1326, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glaser S, Lam IP, Franchitto A, Gaudio E, Onori P, Chow BK, Wise C, Kopriva S, Venter J, White M, Ueno Y, Dostal D, Carpino G, Mancinelli R, Butler W, Chiasson V, DeMorrow S, Francis H, Alpini G. Knockout of secretin receptor reduces large cholangiocyte hyperplasia in mice with extrahepatic cholestasis induced by bile duct ligation. Hepatology 52: 204–214, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grantham JJ. Lillian Jean Kaplan International Prize for advancement in the understanding of polycystic kidney disease. Understanding polycystic kidney disease: a systems biology approach. Kidney Int 64: 1157–1162, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Green GM, Taguchi S, Friestman J, Chey WY, Liddle RA. Plasma secretin, CCK, and pancreatic secretion in response to dietary fat in the rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 256: G1016–G1021, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guay-Woodford LM, Desmond RA. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: the clinical experience in North America. Pediatrics 111: 1072–1080, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gunnes P, Reikeras O. Distribution of the increased cardiac output secondary to the vasodilating and inotropic effects of secretin. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 47: 383–388, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higashihara E, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Grantham JJ, Bae K, Watnick TJ, Horie S, Nutahara K, Ouyang J, Krasa HB, Czerwiec FS. Tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: three years' experience. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2499–2507, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirata K, Nathanson MH. Bile duct epithelia regulate biliary bicarbonate excretion in normal rat liver. Gastroenterology 121: 396–406, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, Kubly VJ, Bergstralh EJ, Li X, Kim B, King BF, Glockner J, Holmes DR, III, Rossetti S, Harris PC, LaRusso NF, Torres VE. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1052–1061, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kato A, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF. Secretin stimulates exocytosis in isolated bile duct epithelial cells by a cyclic AMP-mediated mechanism. J Biol Chem 267: 15523–15529, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim MS, Lee KY, Chey WY. Plasma secretin concentrations in fasting and postprandial states in dog. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 236: E539–E544, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lager DJ, Qian Q, Bengal RJ, Ishibashi M, Torres VE. The pck rat: a new model that resembles human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. Kidney Int 59: 126–136, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lam IP, Siu FK, Chu JY, Chow BK. Multiple actions of secretin in the human body. Int Rev Cytol 265: 159–190, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lenzen R, Alpini G, Tavoloni N. Secretin stimulates bile ductular secretory activity through the cAMP system. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 263: G527–G532, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lesage G, Glaser SS, Gubba S, Robertson WE, Phinizy JL, Lasater J, Rodgers RE, Alpini G. Regrowth of the rat biliary tree after 70% partial hepatectomy is coupled to increased secretin-induced ductal secretion. Gastroenterology 111: 1633–1644, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu Y, Owyang C. Secretin at physiological doses inhibits gastric motility via a vagal afferent pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 268: G1012–G1016, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Masyuk TV, Masyuk AI, Torres VE, Harris PC, Larusso NF. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology 132: 1104–1116, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mennone A, Alvaro D, Cho W, Boyer JL. Isolation of small polarized bile duct units. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 6527–6531, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paliard P, Partensky C. [Polycystic liver disease with abdominal pain and jaundice treated by two successive “fenestration” procedure (author's transl)]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 4: 854–857, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Romano G, Giagu P, Favret G, Bartoli E. Dual effect of secretin on nephron filtration and proximal reabsorption depending on the route of administration. Peptides 21: 723–728, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi A, Ondei P, Fasolini G, Antiga L, Ene-lordache B, Remuzzi G, Epstein FH. Safety and efficacy of long-acting somatostatin treatment in autosomal dominant polcysytic kidney disease. Kidney Int 68: 206–216, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tietz PS, Marinelli RA, Chen XM, Huang B, Cohn J, Kole J, McNiven MA, Alper S, LaRusso NF. Agonist-induced coordinated trafficking of functionally related transport proteins for water and ions in cholangiocytes. J Biol Chem 278: 20413–20419, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Torres VE. Cyclic AMP, at the hub of the cystic cycle. Kidney Int 66: 1283–1285, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 369: 1287–1301, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Torres VE, Meijer E, Bae KT, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang JJ, Czerwiec FS. Rationale and design of the TEMPO (Tolvaptan Efficacy and Safety in Management of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and its Outcomes) 3–4 Study. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 692–699, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH. Effective treatment of an orthologous model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med 10: 363–364, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Vanslembrouck R, van Oijen MG, Hoffmann AL, Dekker HM, de Man RA, Drenth JP. Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 137: 1661–1668 e1661–1662, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wallace DP. Cyclic AMP-mediated cyst expansion. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 1291–1300, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang X, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Harris PC, Torres VE. Vasopressin directly regulates cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 102–108, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu G, D'Agati V, Cai Y, Markowitz G, Park J, Reynolds D, Maeda Y, Le T, Hou H, Jr, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W, Somlo S. Somatic inactivation of PKD2 results in polycystic kidney disease. Cell 93: 177–188, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yamaguchi T, Pelling J, Ramaswamy N, Eppler J, Wallace D, Nagao S, Rome L, Sullivan L, Grantham J. cAMP stimulates the in vitro proliferation of renal cyst epithelial cells by activating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Kidney Int 57: 1460–1471, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]