Abstract

Resident muscle stem cells, known as satellite cells, are thought to be the main mediators of skeletal muscle plasticity. Satellite cells are activated, replicate, and fuse into existing muscle fibers in response to both muscle injury and mechanical load. It is generally well-accepted that satellite cells participate in postnatal growth, hypertrophy, and muscle regeneration following injury; however, their role in muscle regrowth following an atrophic stimulus remains equivocal. The current study employed a genetic mouse model (Pax7-DTA) that allowed for the effective depletion of >90% of satellite cells in adult muscle upon the administration of tamoxifen. Vehicle and tamoxifen-treated young adult female mice were either hindlimb suspended for 14 days to induce muscle atrophy or hindlimb suspended for 14 days followed by 14 days of reloading to allow regrowth, or they remained ambulatory for the duration of the experimental protocol. Additionally, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was added to the drinking water to track cell proliferation. Soleus muscle atrophy, as measured by whole muscle wet weight, fiber cross-sectional area, and single-fiber width, occurred in response to suspension and did not differ between satellite cell-depleted and control muscles. Furthermore, the depletion of satellite cells did not attenuate muscle mass or force recovery during the 14-day reloading period, suggesting that satellite cells are not required for muscle regrowth. Myonuclear number was not altered during either the suspension or the reloading period in soleus muscle fibers from vehicle-treated or satellite cell-depleted animals. Thus, myonuclear domain size was reduced following suspension due to decreased cytoplasmic volume and was completely restored following reloading, independent of the presence of satellite cells. These results provide convincing evidence that satellite cells are not required for muscle regrowth following atrophy and that, instead, the myonuclear domain size changes as myofibers adapt.

Keywords: BrdU, hindlimb suspension, muscle plasticity, Pax7, reloading

satellite cells are resident muscle stem cells located between the sarcolemma and the myofiber basal lamina. Following postnatal development they remain largely quiescent under resting conditions, but become activated in response to muscle injury, stretch, and mechanical load (29). Upon activation, satellite cells replicate and fuse into existing myofibers, providing a local self-renewing repair system. Their ability to self-renew and thus provide an ever ready pool of progenitor cells has logically placed them at the forefront of investigations concerning skeletal muscle plasticity. Given that skeletal muscle fibers are postmitotic, satellite cell fusion into existing myofibers has long been thought to be the main route of muscle adaptation and regeneration (29).

Until recently, direct manipulations of satellite cells to directly examine their role in adult skeletal muscle plasticity were unobtainable. Investigators often used γ-irradiation as a method to perturb DNA synthesis and thus block satellite cell proliferation (16), but the lack of specificity of this approach made it impossible to definitively determine the role of satellite cells in mature muscle adaptations. The identification of the paired box transcription factor, Pax7, as a marker specific to both activated and quiescent satellite cells (30) has enabled us to directly monitor the role of satellite cells during various modalities of muscle adaptation including mechanical overload and regeneration following injury. It is generally well-accepted that Pax7 plays a crucial role in development given that Pax7-null mice display abnormal growth and have a less than 10% survival rate to adulthood (21). Recent research has highlighted the differential genetic requirements for Pax7 in adult muscle stem cells versus embryonic progenitor cells, showing a clear dependency on Pax7 at embryonic stages, whereas, adult muscle stem cells have no such dependence on Pax7 for normal function (13).

Adult muscle regeneration is often described as a process that mirrors the embryonic sequence of events leading to nascent myofiber formation (18), and a series of recent papers using Pax7-driven Cre-dependent recombination to specifically ablate satellite cells clearly shows the absolute necessity of satellite cells for adult muscle regeneration following injury (14, 15, 19, 24). On the other hand, our lab recently demonstrated that adult mouse muscle displayed a normal hypertrophic response after satellite cell depletion using a compensatory overload model (15). These novel findings suggest that muscle regeneration following an acute injury and adult muscle growth (hypertrophy) in response to mechanical overload have different satellite cell requirements.

It remains to be determined if mature muscle regrowth following an atrophic stimulus is dependent on satellite cell participation. The need for satellite cells during muscle regrowth has been investigated in actively growing rodents, and satellite cells appear to play a role in regrowth following muscle atrophy (12, 16, 20). Although there is some debate in the field (9), considerable literature also supports the idea that satellite cells are required for muscle regrowth in adult animals. One proposed mechanism of regrowth is that satellite cells fuse into myofibers to replace myonuclei lost via apoptosis under atrophic conditions to maintain a stable myonuclear domain (1, 8, 10, 16, 25). The myonuclear domain theory posits that each myonucleus is responsible for a set amount of cytoplasm and that the ratio between myonuclei and cytoplasm remains relatively constant (1). Therefore, to preserve a stable myonuclear domain, nuclei would have to be lost with atrophy and gained with hypertrophy or regrowth after atrophy, presumably by satellite cell fusion. However, a recent study by Bruusgaard et al. (4) found that there was no loss of nuclei following hindlimb suspension, despite elevated apoptotic activity within the muscle. Furthermore, despite complete muscle recovery following unloading-induced muscle atrophy, there was no evidence of myonuclear accretion during the reloading period (4). To address this controversy, a mouse model of hindlimb unloading and reloading following satellite cell depletion was employed to test the hypothesis that satellite cells are required for muscle regrowth. The goal was to establish the role of satellite cells in muscle regrowth and determine if this process more closely resembles muscle hypertrophy, muscle regeneration, or is a distinct remodeling process.

METHODS

Animal model.

The Pax7-DTA mouse is a genetic mouse model that allows for the conditional and specific depletion of Pax7-expressing cells (satellite cells) upon tamoxifen administration. The Pax7-DTA mouse was generated by crossing the Pax7CreER/CreER and the Rosa26DTA/DTA as previously described (15). All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kentucky. Mice were housed in a temperature and humidity-controlled room and maintained on a 14:10-h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

Experimental design.

Young adult (4–5 mo) female Pax7-DTA mice (n = 7–13 per group) were randomly assigned to receive either an intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen at a dose of 2.5 mg/day for 5 days, or vehicle only, containing 15% ethanol in sunflower seed oil, followed by a 2-wk washout period. Vehicle- and tamoxifen-treated mice were divided into three groups: ambulatory, suspended for 14 days, or suspended 14 days-reloaded 14 days. Additionally, to identify proliferating cells and any subsequent fusion event, BrdU (5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine), a thymidine analog that is incorporated into newly synthesized DNA, was added to the drinking water (0.80 mg/ml) either during the 14-day ambulatory period, suspension period, or during the 14-day reloading period. Immediately following euthanasia, soleus and gastrocnemius muscles were either analyzed immediately or frozen and stored at −80°C for further analyses as described below.

Hindlimb suspension and reloading protocol.

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of 95% oxygen and 5% isoflurane gas and quickly attached, via cynoacrylate glue, to a tail suspension apparatus consisting of a 1-in. wire leader with a swivel end. The wire leader was then threaded through a metal rod attached to the top of a standard rodent cage. The mice were suspended at an angle that allowed for the complete removal of any hindlimb contact with the cage floor. The animals had free access to food and water ad libitum and were assessed twice daily for proper suspension position and wellness. Following the 14-day suspension period a subset of animals were reloaded by gently peeling away the wire leader from the tail allowing the hindlimbs to bear weight.

Immunohistochemistry.

Soleus muscles were dissected from surrounding connective tissue, weighed, pinned to a cork block at resting length, covered with a thin layer of OCT compound, and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and stored at −80°C before sectioning. Sections (7 μm) were immunohistochemically analyzed for Pax7 (satellite cells), and dystrophin (sarcolemma), BrdU (cell proliferation) and stained with DAPI (10 nM) (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to visualize nuclei. Images were captured using an Axioimager MI upright fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany), and all analyses were performed using AxioVision Rel software (version 4.8).

Pax7.

Pax7 detection was determined on sections fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently exposed to an epitope retrieval protocol using sodium citrate (10 mM, pH 6.5) at 92°C. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS, followed by incubation with the Mouse-on-Mouse Blocking Reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Following incubation with Pax7 antibody (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Study Bank, Iowa City, IA) at a 1:100 dilution, sections were incubated with a goat anti-mouse biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) in PBS followed by the streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (1:100) included as part of the Tyramide Signal Amplification kit (TSA) (Invitrogen). TSA-Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen) was used to visualize antibody-binding. Sections were then counterstained with DAPI (10 nM) (Invitrogen), washed, and mounted with Vectashield fluorescent mounting media (Vector Laboratories). Pax7+/DAPI+ nuclei were counted and normalized per fiber.

Dystrophin/DAPI/BrdU.

The dystrophin antibody (1:50) (Vector Laboratories) was applied to fresh-frozen sections followed by Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA). Sections were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then stained with DAPI, unless BrdU detection was performed. Following dystrophin detection, sections were fixed in absolute methanol, treated with 2 N HCl to denature DNA, and neutralized with 0.1 M borate buffer (BORAX), pH 8.5. BrdU antibody incubation (1:100 Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was followed by biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and streptavidin-FITC (1:150) (Vector Laboratories). The dystrophin-positive sarcolemma was traced and used to assess soleus fiber cross-sectional area (μm2). Approximately 200–800 fibers per animal were traced and used to calculate mean soleus fiber cross-sectional area. BrdU+ nuclei within the dystrophin boundary were counted and are represented as percentage of total fibers within a given soleus muscle cross section that contained a BrdU+ nucleus. Conversely, central nucleation was assessed by counting DAPI+ nuclei, with clear separation from the dystrophin boundary. The data are presented as the centrally located nuclei per soleus cross section.

Soleus single-fiber isolation.

After careful removal of the other plantar flexor muscles, soleus muscles were left on the tibia and fixed in situ at resting length in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h. Single fibers were isolated by a previously described method (3). Briefly, following a 2-h 40% NaOH digestion, single fibers were mechanically teased apart, strained, and washed with PBS before being stained with DAPI for nuclear visualization. Suspended fibers were dispersed on a slide and mounted with Vectashield fluorescent mounting media (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured at ×20 magnification using an Axioimager MI upright microscope (Zeiss) and all fiber and nuclear measurements were made using AxioVision Rel software (version 4.8). Fifteen fibers from each animal were measured for fiber width (μm) and subsequently the nuclei from each fiber were counted by z-stack analysis to determine the number of myonuclei per defined fiber segment (myonuclear domain). Myonuclear domain is defined as the amount of cytoplasm per myonucleus and was calculated by multiplying π × one-half the fiber width (radius)2 × length of the measured fiber segment, to give a fiber segment volume (μm3), which was then divided by the total number of myonuclei within the segment to generate the myonuclear domain.

Real-time qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from frozen gastrocnemius muscles (n = 5 per group) using the ToTALLY RNA kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) per the manufacturer's directions. Approximately 60 mg of muscle were pulverized in liquid nitrogen and further homogenized using a rotating tissue homogenizer (ProScientific, Oxford, CT). Following isolation, RNA samples were treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion) and RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermoscientific, Wilmington, DE). cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA using qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pax7 gene expression was analyzed using a TaqMan gene expression assay employing a predesigned Pax7 primer (no. 955749, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and a 20× TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix containing both a reporter and probe (Applied Biosystems). A six point standard curve was prepared from pooled samples using known RNA equivalents ranging from 25 ng to 0.125 ng and used to quantify experimental samples. Data are expressed as RNA equivalents normalized to RNA input.

Force analyses.

Gastrocnemius muscles from ambulatory and reloaded animals were immediately dissected and prepared for in vitro force analyses to evaluate single-fiber functional recovery following unloading. Single-fiber preparations were prepared as previously described in detail (6). Briefly, muscle fibers were chemically permeabilized with Triton X-100 and attached to a force transducer (403, Aurora Scientific, resonant frequency 600 Hz) and a motor (312B, Aurora, step-time 0.6 ms). Steady-state force and tension recovery kinetics were measured as a function of the activating Ca2+ concentration.

Statistics.

Data were analyzed with SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) via a two-factor ANOVA. If a significant interaction was detected, an appropriate post hoc analysis was employed to determine the source of the significance. Statistical significance was accepted at P ≤ 0.05. Data are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Efficient depletion of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle.

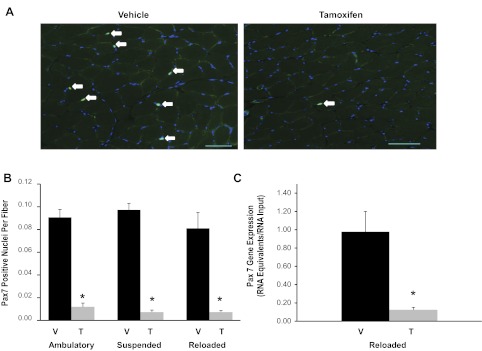

The efficiency of tamoxifen-induced satellite cell depletion was measured by immunohistochemistry and real-time qRT-PCR. Quantification of Pax7+/DAPI+ satellite cells in soleus muscles (Fig. 1A, white arrows) demonstrated over 90% depletion across all groups of tamoxifen- compared with vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 1, A and B). Similarly, Pax7 gene expression was reduced by 88% in gastrocnemius muscles isolated from tamoxifen-treated reloaded animals compared with their reloaded vehicle-treated counterparts (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Efficient conditional depletion of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. A: Pax7 immunohistochemistry was performed on soleus muscle cross sections (7 μm) from vehicle- and tamoxifen-treated animals to detect the presence of satellite cells (green). Sections were counterstained with DAPI (blue), and Pax7+/DAPI+ nuclei were quantified (white arrows). Scale bar, 50 μm. B: quantification of Pax7+/DAPI+ nuclei. Data are represented as Pax7+ nuclei per fiber ± SE. C: Pax7 gene expression was assessed in gastrocnemius muscles from reloaded animals using qRT-PCR. Values are presented as means ± SE. Black bars represent vehicle-treated animals (V) and gray bars represent tamoxifen-treated animals (T). *Significant effect of tamoxifen between condition-matched groups; P ≤ 0.05.

Effective muscle regrowth following atrophy in satellite cell-depleted muscle.

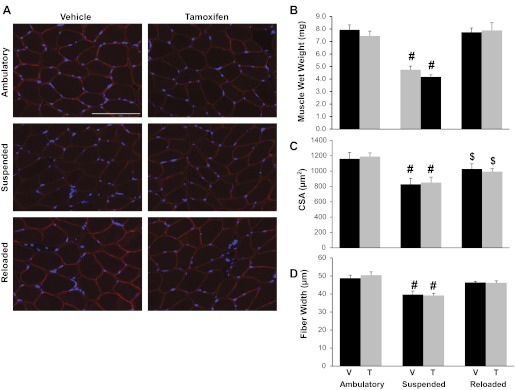

Muscle regrowth following unloading induced-atrophy was assessed in soleus muscles via three measurements of muscle size: muscle wet weight (mg), myofiber cross-sectional area (μm2) determined from immunohistochemistry, and myofiber width (μm) measured from isolated single fiber preparations (Fig. 2). As expected, 14 days of suspension elicited a marked atrophic response in soleus muscles. Soleus muscle wet weight was decreased ∼40% in both tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated animals. Surprisingly, following 14 days of reloading, soleus muscle wet weight was completely recovered in both treatment groups (Fig. 2B). Similarly, soleus mean myofiber cross-sectional areas, quantified on dystrophin-labeled muscle cross sections (Fig. 2, A and C), were reduced by 28.6% as a result of suspension regardless of satellite cell content, and satellite cell-depleted muscle recovered from atrophy to the same degree as nonablated muscles (Fig. 2C). However, mean myofiber cross-sectional areas from both groups remained significantly depressed compared with their ambulatory counterparts (Fig. 2C). Lastly, soleus myofiber width assessed from isolated single fiber preparations was in agreement with both muscle wet weight and cross-sectional area measurements; the extent of atrophy and recovery following hindlimb suspension was independent of satellite cell depletion (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Effective muscle regrowth following atrophy in satellite cell-depleted muscle. A: representative soleus muscle cross sections from each experimental group immunoreacted with the dystrophin antibody (red) and stained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei. Scale bar, 50 μm. B: soleus muscle wet weight (mg) was assessed immediately after dissection. C: mean soleus muscle fiber cross-sectional areas (CSA) were quantified by tracing dystrophin-labeled fibers. D: mean soleus fiber width (μm) was calculated by averaging the fiber width of a minimum of 15 isolated fixed soleus fibers per animal (n = 7–13) from each experimental group. Values are presented as means ± SE. Black bars represent vehicle-treated animals and gray bars represent tamoxifen-treated animals. #Significant difference between treatment-matched ambulatory and suspended animals; $significant difference between treatment-matched reloaded and ambulatory animals; P ≤ 0.05.

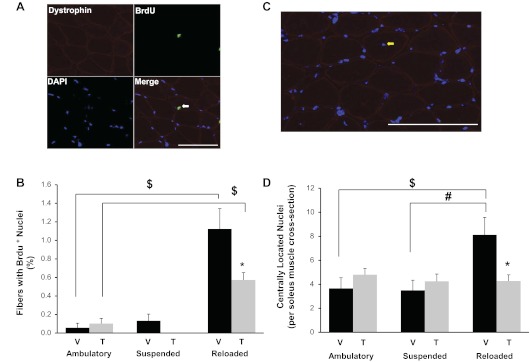

Increased satellite cell fusion and central nucleation in response to reloading is attenuated in satellite cell-depleted muscles.

Since muscle size regulation was not affected by satellite cell depletion, nuclear addition due to satellite cell fusion was measured. BrdU incorporation was used to quantify cell proliferation and fusion of labeled nuclei into myofibers. Given that myofibers are postmitotic, a BrdU-labeled nucleus within the dystrophin boundary represents a cell (most likely a satellite cell) that has divided and fused into the myofiber (Fig. 3A). BrdU labeling within myofibers was extremely low across all groups regardless of treatment (vehicle or tamoxifen) or condition (ambulation, suspension, or reloading) with <0.2% of myonuclei labeling positive for BrdU. BrdU+ myonuclei were elevated by reloading in both vehicle- and tamoxifen-treated animals, but the increase was significantly greater in vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 3, A and B). Even in those mice, the proportion of myofibers containing a BrdU+ nucleus represented only ∼1% of the total myofibers within an entire soleus muscle cross section (Fig. 3, A and B). Thus, regardless of satellite cell status, myonuclear addition during regrowth in this adult mouse model appears to be minimal.

Fig. 3.

Satellite cell proliferation and myofiber central nucleation were elevated in response to reloading and attenuated in satellite cell-depleted muscles. A: soleus muscle cross sections were examined immunohistochemically for 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (green) and dystrophin (red) and costained with DAPI (blue). Representative image of BrdU+/DAPI+ nucleus inside a myofiber (white arrow). Scale bar, 50 μm. B: quantification of BrdU+ nuclei. Data are presented as the percentage of total myofibers containing a BrdU+ nucleus. C: representative image from a reloaded vehicle-treated soleus muscle cross section showing a centrally located nucleus (yellow arrow). Scale bar, 50 μm. D: qantification of centrally located nuclei. Data are represented as the total number of central nuclei per whole soleus cross section. Values are presented as means ± SE. Black bars represent vehicle-treated animals and gray bars represent tamoxifen-treated animals. *Significant effect of tamoxifen from condition-matched groups; #significant difference between treatment-matched suspended and reloaded animals; $significant difference between treatment-matched reloaded and ambulatory animals; P ≤ 0.05.

Central nucleation, often used as a marker of muscle regeneration, was quantified by counting the number of DAPI+ nuclei inside the myofiber, but separated from the dystrophin-labeled sarcolemma (Fig. 3C). The number of centrally located nuclei doubled with reloading in soleus muscles from vehicle-treated compared with satellite cell-ablated muscles (Fig. 3D). However, similar to BrdU labeling, central nucleation remained a rare event, even in reloaded animals, suggesting that in our hands, muscle reloading following atrophy elicits only a minor regenerative response.

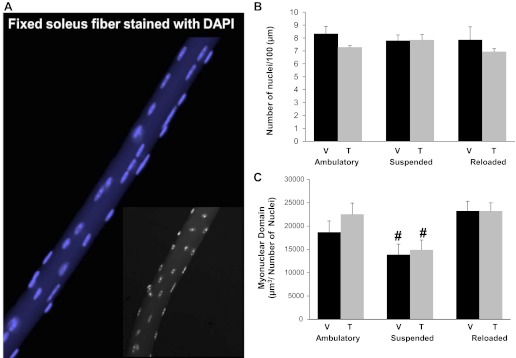

Myonuclear number remained constant across all experimental conditions, resulting in a smaller myonuclear domain in atrophied muscle.

Myonuclear counts from single fiber preparations (illustrated in Fig. 4A) showed that the number of myonuclei per 100 μm of fiber length did not differ across the experimental conditions. Thus, no loss or addition of nuclei to soleus myofibers undergoing atrophy or during regrowth was apparent (Fig. 4B). As a result, myonuclear domain was significantly decreased in soleus muscle fibers in response to suspension (Fig. 4C) and there was no effect of satellite cell depletion. Furthermore, given the constant myonuclear number, the reduction seen in myonuclear domain with suspension was driven solely by the reduction in cytoplasmic volume. These data confirm the BrdU measurements and indicate that satellite cell fusion likely plays a minimal role in regrowth after atrophy.

Fig. 4.

Myonuclear number remained constant across all experimental conditions, whereas myonuclear domain was reduced following suspension regardless of satellite cell depletion. A: representative image of an isolated fiber from a soleus muscle stained with DAPI (blue) to identify myonuclei. Inset: black and white image of an isolated fiber. B: myonuclear number was assessed in isolated soleus fibers. Nuclei were counted and represented as myonuclei per 100 μm of fiber length. C: myonuclear domain was determined by calculating the volume of a fiber segment (μm3) and normalizing to the number of myonuclei within the given segment. Values are presented as means ± SE. Black bars represent vehicle-treated animals and gray bars represent tamoxifen-treated animals. #Significant difference between treatment-matched ambulatory and suspended animals; P ≤ 0.05.

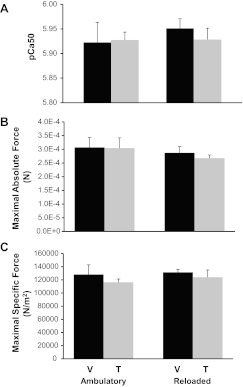

Specific force and calcium sensitivity were maintained in single fibers isolated from satellite cell-depleted animals.

To investigate whether a decrease of over 90% in satellite cell number had any effect on functional recovery from atrophy, single fibers were prepared for functional analyses from gastrocnemius muscles dissected from both ambulatory and reloaded animals to determine whether satellite cell depletion affected single-fiber function. pCa50 (the concentration of Ca2+ necessary to produce one-half maximal tension expressed as pCa50 units) was unaffected by satellite cell depletion (Fig. 5A). Similarly, force production at maximally activating Ca2+ concentration was not affected by either reloading or satellite cell depletion, whether represented absolutely (N) (Fig. 5B) or as specific force normalized to fiber area (N/m2) (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that Ca2+ sensitivity and maximal force production were unaffected in satellite cell-depleted myofibers recovering from disuse.

Fig. 5.

Specific force and calcium sensitivity were maintained in single fibers isolated from satellite cell-depleted animals. A: pCa50 represents the Ca2+ concentration that elicited one-half the maximal tension expressed in pCa50 units. B: absolute maximal force (N) was evaluated for single fiber preparations at maximally activating Ca2+ concentrations. C: specific force (N/m2) represents maximal force normalized to fiber area. Values are presented as means ± SE. Black bars represent vehicle-treated animals and gray bars represent tamoxifen-treated animals.

DISCUSSION

The postmitotic nature of skeletal muscle fibers requires an intrinsic repair mechanism to replace myonuclei lost during injury, disease and/or normal turnover. The dogma established over the past several decades is that the distinctive capacity of muscle to adapt to different perturbations by either increasing cell (fiber) size in response to mechanical load, or to repair following injury, depends on the presence of local muscle stem cells known as satellite cells (29). The role of satellite cells in muscle regeneration is well defined, and recent studies using genetic models convincingly demonstrated that with satellite cell depletion, muscle regeneration is severely attenuated (14, 19, 24). Furthermore, muscle hypertrophy has been shown to involve myonuclear accretion (15, 28), although effective myofiber growth occurs without satellite cell-dependent myonuclear addition (15).

Data from the current study indicate that regrowth following atrophy is a distinct process, divergent from both muscle hypertrophy and regeneration. Muscle regrowth did not result in myonuclear addition, although a very mild regenerative response was observed by slight increases in central nucleation and BrdU incorporation; however, these responses were eliminated (central nucleation) or attenuated (BrdU incorporation) by satellite cell depletion, indicating that satellite cells had limited participation in muscle regrowth following unloading. Thus, in our hands, hindlimb unloading followed by reloading in adult mice did not result in a substantial satellite cell-dependent regenerative response contrary to other reports (18, 26). The magnitude of BrdU incorporation seen in the current study is blunted compared with other rodent reloading studies likely due to age differences in the animals used (8, 20) and thus may be more representative of the role of satellite cells in mature skeletal muscle regrowth. More importantly, complete recovery of muscle weight, fiber width, fiber cross-sectional area, and force following reloading was observed in muscles from tamoxifen-treated Pax7-DTA mice in which over 90% of satellite cells were ablated. Although it is difficult to ascertain the role that the remaining population of satellite cells may have played in muscle regrowth, considering the absence of central nucleation and the very low percentage (∼0.5%) of fibers containing BrdU+ myonuclei in tamoxifen-treated reloaded animals, these data suggest that substantial regrowth of muscle occurs without the addition of new myonuclei or considerable satellite cell fusion. Furthermore, in similar models of satellite cell depletion the remaining satellite cells were unable to rescue muscle regeneration (14, 19) and therefore they are likely below the threshold necessary to adequately assist in muscle recovery from atrophy.

The results of the current investigation demonstrate that myofiber atrophy and regrowth are not associated with changes in myonuclear number. Despite a ∼40% decrease in muscle wet weight and a ∼25% loss in mean fiber width, there was no loss of myonuclei during 14 days of unloading. Although there is a substantial body of literature demonstrating myonuclear loss during muscle atrophy (2, 10, 16), our results are consistent with studies showing no myonuclear loss following hindlimb unloading in adult rodents (4, 11). The divergent results surrounding myonuclear loss with atrophy may be due to differing species (rat vs. mouse), different modalities of atrophy [denervation (27), spinal cord injury (7), antigravity (10), versus hindlimb suspension (4)], the age of the animals involved, and/or the means by which myonuclear number was assessed [through immunohistochemistry on cross sections (10), in isolated single fibers (3), or through in vivo nuclear labeling (5)]. In any case, the absence of myonuclear loss during atrophy observed here resulted in a smaller myonuclear domain that returned to control size following reloading, obviating the necessity of satellite cells to replace myonuclei. We recently showed that normal myofiber hypertrophy and force generation, in the absence of myonuclear accretion, occurred in response to compensatory overload of the plantaris muscle in tamoxifen-treated Pax7-DTA mice, resulting in a significantly larger myonuclear domain (15). It is possible that myonuclear accretion through satellite cell fusion and myofiber hypertrophy are not temporally coordinated (28) such that deficits in muscle growth may occur at later time points; however, taken together these studies show that the ratio between myonuclei and cytoplasmic volume is altered during muscle adaptation, allowing for large increases in domain size with overload (15) and considerable decreases with hindlimb unloading. Thus, the myonuclear domain appears to be remarkably flexible depending on physiological conditions, and therefore processes involved in protein turnover may be more important than the regulation of satellite cells.

The findings of the current investigation do not concur with the study by Mitchell and Pavlath (16) in which γ-irradiation was used to eliminate satellite cells during suspension and subsequent regrowth. Irradiation prevented complete muscle regrowth following hindlimb unloading at 14 days even though early muscle regrowth proceeded normally. It was suggested that initiation of muscle regrowth was independent of satellite cell involvement (16). However, that study utilized immature growing mice which may have different satellite cell requirements for regrowth following disuse (17, 23). Alternatively, irradiation may have had nonspecific effects in addition to the elimination of satellite cells.

The present study argues against the utility of satellite cells as therapeutic targets to aide in recovery from atrophy following prolonged muscle disuse or bed rest subsequent to injury or chronic illness. However, it is possible that recovery from multiple exposures to an atrophic stimulus (such as bed rest) may still require satellite cell participation, even though the depletion of satellite cells did not perturb muscle recovery acutely, or following only one bout of unloading. It has also been suggested that a myonuclear domain ceiling exists in human muscle fibers following resistance exercise training (22) and therefore the requirement for additional myonuclei for muscle growth and/or regrowth may be species-specific. Consequently, continuing to delineate the role of satellite cells in muscle recovery from atrophy is paramount to unlocking their restorative potential.

In conclusion, satellite cell depletion did not alter the muscle response to reloading, suggesting that muscle precursor cells are not a prerequisite for acute muscle regrowth following an atrophic stimulus. Previous studies demonstrate that satellite cells are absolutely required for muscle regeneration following injury; in addition, satellite cells considerably participate in muscle hypertrophy, even though they are dispensable for short-term growth. Thus, muscle regrowth following unloading appears to be a distinct remodeling process that is not dependent on satellite cells, highlighting the contrasting contribution of satellite cells in different models of muscle plasticity.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG034453 (to C. A. Peterson) and AR060701 (to C. A. Peterson and J. J. McCarthy). Functional assays were partially supported by seed funds from the University of Kentucky Center for Muscle Biology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.R.J., C.S.F., J.D.L., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. conception and design of the research; J.R.J., J.M., T.J.K., C.S.F., and J.D.L. performed the experiments; J.R.J., J.M., T.J.K., M.F.U., and K.S.C. analyzed the data; J.R.J., T.J.K., K.S.C., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. interpreted the results of the experiments; J.R.J. and J.M. prepared the figures; J.R.J. and E.E.D.-V. drafted the manuscript; J.R.J., C.S.F., J.D.L., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. edited and revised the manuscript; J.R.J., C.S.F., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Rod Erfani and Benjamin Lawson for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen DL, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Myonuclear domains in muscle adaptation and disease. Muscle Nerve 22: 1350–1360, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen DL, Yasui W, Tanaka T, Ohira Y, Nagaoka S, Sekiguchi C, Hinds WE, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Myonuclear number and myosin heavy chain expression in rat soleus single muscle fibers after spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 81: 145–151, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brack AS, Bildsoe H, Hughes SM. Evidence that satellite cell decrement contributes to preferential decline in nuclear number from large fibres during murine age-related muscle atrophy. J Cell Sci 118: 4813–4821, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruusgaard JC, Egner IM, Larsen TK, Dupre-Aucouturier S, Desplanches D, Gundersen K. No change in myonuclear number during muscle unloading and reloading. J Appl Physiol 113: 290–296, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruusgaard JC, Gundersen K. In vivo time-lapse microscopy reveals no loss of murine myonuclei during weeks of muscle atrophy. J Clin Invest 118: 1450–1457, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell KS. Tension recovery in permeabilized rat soleus muscle fibers after rapid shortening and restretch. Biophys J 90: 1288–1294, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupont-Versteegden EE, Murphy RJ, Houle JD, Gurley CM, Peterson CA. Activated satellite cells fail to restore myonuclear number in spinal cord transected and exercised rats. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C589–C597, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallegly JC, Turesky NA, Strotman BA, Gurley CM, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Satellite cell regulation of muscle mass is altered at old age. J Appl Physiol 97: 1082–1090, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gundersen K, Bruusgaard JC. Nuclear domains during muscle atrophy: nuclei lost or paradigm lost? J Physiol 586: 2675–2681, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hikida RS, Van Nostran S, Murray JD, Staron RS, Gordon SE, Kraemer WJ. Myonuclear loss in atrophied soleus muscle fibers. Anat Rec 247: 350–354, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasper CE, Xun L. Cytoplasm-to-myonucleus ratios in plantaris and soleus muscle fibres following hindlimb suspension. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 17: 603–610, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawano F, Takeno Y, Nakai N, Higo Y, Terada M, Ohira T, Nonaka I, Ohira Y. Essential role of satellite cells in the growth of rat soleus muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C458–C467, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepper C, Conway SJ, Fan CM. Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature 460: 627–631, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepper C, Partridge TA, Fan CM. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3639–3646, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy JJ, Mula J, Miyazaki M, Erfani R, Garrison K, Farooqui AB, Srikuea R, Lawson BA, Grimes B, Keller C, Van Zant G, Campbell KS, Esser KA, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Peterson CA. Effective fiber hypertrophy in satellite cell-depleted skeletal muscle. Development 138: 3657–3666, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell PO, Pavlath GK. A muscle precursor cell-dependent pathway contributes to muscle growth after atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1706–C1715, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell PO, Pavlath GK. Skeletal muscle atrophy leads to loss and dysfunction of muscle precursor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1753–C1762, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mozdziak PE, Pulvermacher PM, Schultz E. Muscle regeneration during hindlimb unloading results in a reduction in muscle size after reloading. J Appl Physiol 91: 183–190, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3625–3637, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano J, Kataoka H, Sakamoto J, Origuchi T, Okita M, Yoshimura T. Low-level laser irradiation promotes the recovery of atrophied gastrocnemius skeletal muscle in rats. Exp Physiol 94: 1005–1015, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oustanina S, Hause G, Braun T. Pax7 directs postnatal renewal and propagation of myogenic satellite cells but not their specification. EMBO J 23: 3430–3439, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrella JK, Kim JS, Cross JM, Kosek DJ, Bamman MM. Efficacy of myonuclear addition may explain differential myofiber growth among resistance-trained young and older men and women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E937–E946, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenblatt JD, Parry DJ. Gamma irradiation prevents compensatory hypertrophy of overloaded mouse extensor digitorum longus muscle. J Appl Physiol 73: 2538–2543, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambasivan R, Yao R, Kissenpfennig A, Van Wittenberghe L, Paldi A, Gayraud-Morel B, Guenou H, Malissen B, Tajbakhsh S, Galy A. Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3647–3656, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siu PM, Pistilli EE, Alway SE. Apoptotic responses to hindlimb suspension in gastrocnemius muscles from young adult and aged rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1015–R1026, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tidball JG, Wehling-Henricks M. Macrophages promote muscle membrane repair and muscle fibre growth and regeneration during modified muscle loading in mice in vivo. J Physiol 578: 327–336, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Meer SF, Jaspers RT, Jones DA, Degens H. Time-course of changes in the myonuclear domain during denervation in young-adult and old rat gastrocnemius muscle. Muscle Nerve 43: 212–222, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Meer SF, Jaspers RT, Jones DA, Degens H. The time course of myonuclear accretion during hypertrophy in young adult and older rat plantaris muscle. Ann Anat 193: 56–63, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zammit PS, Partridge TA, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold. J Histochem Cytochem 54: 1177–1191, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zammit PS, Relaix F, Nagata Y, Ruiz AP, Collins CA, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR. Pax7 and myogenic progression in skeletal muscle satellite cells. J Cell Sci 119: 1824–1832, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]