Abstract

Background

While dimensional models of psychopathology have delineated two broad factors underlying common mental disorders – internalizing and externalizing – it is unclear where bipolar disorder and non-affective psychoses fit in relation to this structure and to each other. Given their low prevalence rates in the general population, these disorders generally tend to be excluded from such models. The current study used the person-centered approach of latent class analysis (LCA) to evaluate this question.

Sampling and Methods

LCA of diagnostic data from an epidemiological sample, the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS; N = 5877), was undertaken. Diagnoses utilized in analyses included mania, non-affective psychoses, specific phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, and conduct disorder.

Results

Results indicated that a 5-class LCA model optimally fit the data. Four of the classes mirrored those found in dimensional models – a class with few disorders, and three others with primarily fear, distress, and externalizing disorders. However, the fifth class – which is not evident in dimensional models – was unique in that it was the only one in which individuals demonstrated significant probabilities of both manic episodes and non-affective psychoses in addition to markedly high levels of internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Conclusion

This finding has important implications for nosological classification of psychopathology.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, comorbidity, classification, epidemiology

Introduction

The question of how to classify bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, both in relation to one another and to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, is one that is currently at the forefront of the field [1, 2]. Factor analytic models of common mental disorders in population-representative samples have revealed the presence of two correlated dimensions – internalizing and externalizing – underlying the most common forms of psychopathology, including mood and anxiety, substance use, and antisocial behavior disorders. However, these analytic models have typically excluded bipolar disorder and schizophrenia due to their extremely low prevalence rates [3, 4]. Two recent studies [5, 6] have attempted to remedy this gap. The first of these focused on data from psychiatric inpatient samples [5], whereas the second [6] used symptom level data from an epidemiological sample. In each case, results suggested the presence of a psychosis or thought-disorder dimension that was correlated with internalizing and externalizing dimensions and their subdimensions.

Studies of this kind that have utilized factor analysis to order patients along dimensions can be described as taking a variable-centered approach. That is, this method is concerned with examining the relationships among variables used in the analyses. While this approach has proven useful for modeling patterns of disorder co-occurrence across individuals, the question of how comorbidity manifests within individual patients remains to be addressed, as does the question of why broad dimensions emerge as correlated in factor analytic models. A method well suited to addressing these questions is the person-centered method of latent class analysis (LCA), which assigns individuals to subtypes based on the similarity of their diagnostic profiles. In contrast with factor analysis, LCA can also better accommodate phenomena with low base rates, such as infrequently occurring diagnostic conditions like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. In particular, statisticians have pointed out that LCA can be particularly useful in situations where binary variables (such as diagnoses) are the object of analyses [7]. If intersections exist across dimensions that are not adequately captured by factor analytic models (e.g., certain disorders co-occur with all other disorders, or certain individuals exhibit disorders of all types), then LCA could provide new insights into the phenomenon of comorbidity. In these respects, LCA provides a useful complement to factor analysis as a method for clarifying interrelations among disorders of various types, including disorders with very low population prevalence.

Recent research using LCA to characterize patterns of comorbidity between bipolar I disorder and internalizing and externalizing disorders in individuals from two large epidemiological samples – the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) and the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) – indicated that bipolar I disorder occurred in a highly specific subgroup of individuals – those exhibiting high levels of both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology [8]. Specifically, in each of these participant samples, LCA revealed five distinct comorbid-disorder classes, four of which (“fear,” “distress,” “externalizing,” and “few disorders”) directly paralleled findings from factor analytic models of psychopathology. The fifth class, labeled “multimorbid”, showed elevated levels of all internalizing and externalizing forms of psychopathology, and was also the only class to show significantly elevated levels of bipolar I disorder. These results suggest that individuals prone to experiencing bipolar disorder are also prone to experiencing disorders of various other types. In particular, the multimorbid class was the only subgroup to show elevated probabilities of both internalizing and externalizing disorders, in contrast with other classes that exhibited disorders of primarily one or the other type. One of the participant samples employed in this prior LCA study, the NCS sample, also includes diagnostic data pertaining to “non-affective” psychosis (NAP), a composite category encompassing schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and atypical psychosis that was not included in LCA analyses in the previous study.

The current report extended prior published work by determining the placement of NAP within this LCA-based classification scheme, using data from the NCS. The primary study hypothesis was that bipolar I disorder and NAP would occur at elevated rates primarily in the multimorbid class. Findings in line with this hypothesis would provide additional evidence in support of the proposition that these disorders should be classified together in the official nosology [1, 9].

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Data for the current study were drawn from the NCS, a landmark survey of DSM-IIIR disorders in the general population conducted from 1990–1992 [10]. A total of 8098 participants were assessed for most mood, anxiety, and externalizing disorders contained in the DSM-IIIR using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Out of this larger sample, 5877 participants were administered further questions that included coverage of NAP. This subsample of the NCS was utilized in the current study, and is the same as that utilized in our prior study [8]. As our goal was to delineate patterns of comorbidity among various forms of psychopathology, hierarchy-free lifetime diagnoses were utilized in the analyses. Internalizing and externalizing disorders included in the LCA models consisted of those typically included in dimensional models – i.e., social phobia, specific phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol dependence, drug dependence, and conduct disorder. The internalizing/externalizing framework was chosen as a theoretical referent as it has been shown to replicate across samples and is currently being used to help guide revisions for upcoming versions of the DSM and ICD [11]. With regard to bipolar I disorder, Kessler et al. [12] reported that only manic episodes entailing grandiosity, euphoria, and the ability to maintain energy without sleep could be validly assessed using the CIDI. Accordingly, we adopted this restricted definition of manic episodes in the current study. Notably, an identical pattern of results emerged when analyses incorporated more broadly-defined bipolar I disorder (i.e., incorporating manic episodes of all types). Weighted estimates showed that approximately 42 subjects were diagnosed with NAP, and about 22 with manic episodes; only two subjects in the sample were diagnosed with both.

Statistical Analyses

LCA models were undertaken using the Latent Gold 4.5 software package, which incorporated the complex survey features of the NCS dataset including weighting, clustering, and stratification [13]. Models ranging from 2 to 10 classes were evaluated and compared using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [14]. When comparing models, minimal observed values of BIC are used to determine optimal model fit [15, 16]. Each candidate model was run with 50 starting values and 5 final stage optimization values to avoid problems with local maxima [17].

Results

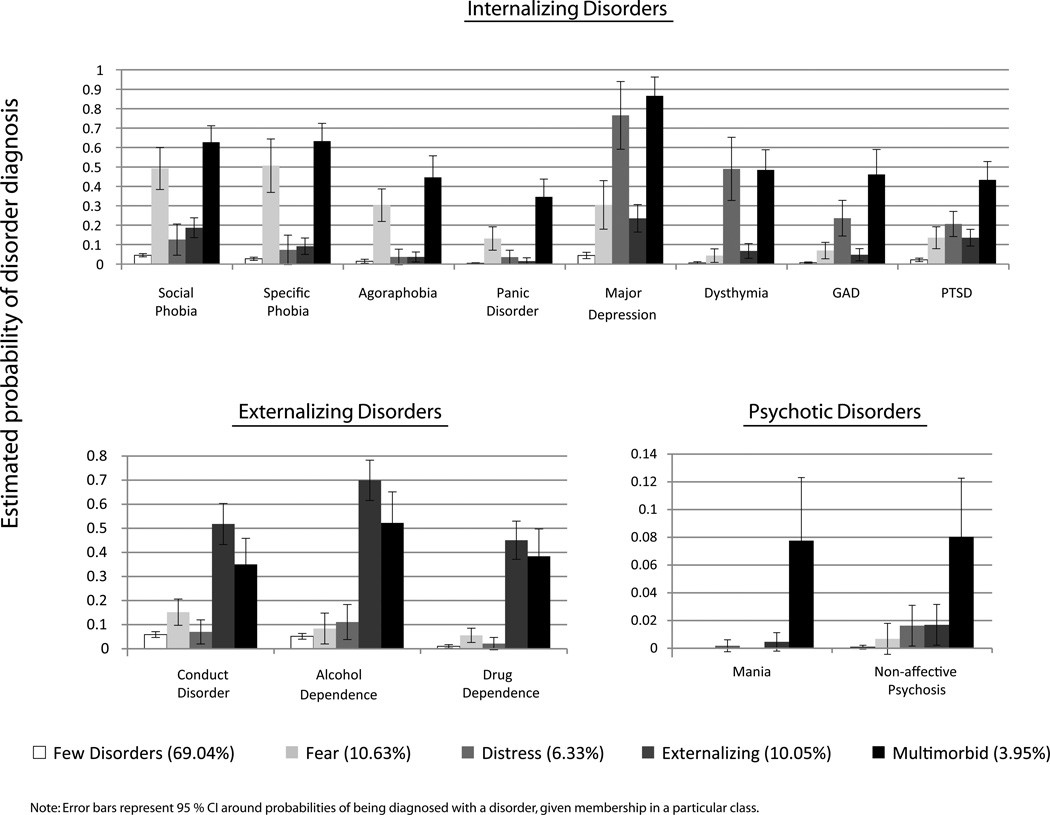

The BIC supported a 5-class model as having the best fit to the data (see Table 1), with individuals distributed across the classes as follows: few disorders (69.04%); two internalizing classes, fear (10.63%) and distress (6.33%); externalizing (10.05%); and multimorbid (3.95%). Based on the parameter estimates provided by the optimal fitting model, it is possible to estimate the probability of disorder diagnosis given membership in a particular class for individuals in each of the five classes, and these values are displayed in Figure 1 (along with 95% confidence intervals; CI). To ease interpretation, the figure separates disorders into internalizing, externalizing, and psychotic subsets, and indicates the likelihood of being diagnosed with each particular disorder in each subset conditional upon membership in each of the five classes.

Table 1.

Model fit indices for latent class analysis models in National Comorbidity Survey sample (N = 5877).

| # of classes | BIC |

|---|---|

| 2 | 36942.14 |

| 3 | 36527.73 |

| 4 | 36376.59 |

| 5 | 36227.90 |

| 6 | 36282.65 |

| 7 | 36339.47 |

| 8 | 36416.57 |

| 9 | 36500.20 |

| 10 | 36589.86 |

Note: BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion. Best-fitting model for each sample is in boldface.

Figure 1.

Estimated probabilities of being diagnosed with a disorder conditional upon membership in each of the five classes, as derived from the best fitting LCA model of the National Comorbidity Survey subsample (NCS; N = 5877).

Consistent with prior work [8], individuals in the fear and distress classes (gray and green bars, respectively, in Figure 1) showed the greatest probability of being diagnosed with internalizing disorders, but not externalizing or psychotic disorders. Conversely, those in the externalizing class (purple bars in Figure 1) evinced the greatest probability of being diagnosed with externalizing disorders, but low probabilities of being diagnosed with internalizing or psychotic disorders. However, the new finding in the current study was that manic episodes and NAP occurred at significantly elevated levels only in the multimorbid class (red bars in Figure 1); individuals in this class were estimated to be more than four times as likely to be diagnosed with these disorders than individuals in any of the other four classes. Additionally, though this was the smallest class obtained in the current study (3.95% of total sample), individuals in this class had markedly elevated probabilities of being diagnosed with both internalizing and externalizing types of disorders, in addition to psychotic disorders.

Discussion

We utilized LCA to delineate patterns of co-occurrence of manic episodes and NAP with internalizing and externalizing disorders in a nationally-representative epidemiological sample. Our analysis showed that both of these rarer forms of psychopathology occurred (a) in one particular group of individuals that (b) exhibited extremely high levels of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders. Some potential limitations of the current work include the use of participants who are noninstitutionalized civilians and exhibit a very low prevalence of manic episodes and non-affective psychosis, and the potential unreliability of diagnoses of psychosis in epidemiologic surveys [18]. Regarding this latter point, however, careful re-analyses of data for NAP [19] and bipolar disorder [12] in the NCS have confirmed the reliability of estimates of these disorders.

Notwithstanding these complexities, in conjunction with prior research that shows similarities between bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia, results from the current study provide further support for the notion that bipolar I disorder and NAP exhibit meaningful similarity--in this case, with respect to patterns of co-occurrence with other psychiatric conditions. Importantly, this result cannot be attributed to individuals being assigned both types of diagnosis, because co-occurrence of the two disorders was evident in only two of the approximately 60 instances where one of these diagnoses was assigned. In turn, this lends weight to arguments that the current nosology should be restructured, perhaps placing bipolar I disorder, schizophrenia, and the other nonaffective psychoses in the same general category, even if more specific risk factors may potentially be found for some of these disorders [1, 2]. This particular question is in fact one that has received special attention in discussions concerning the development of a “metastructure” for DSM disorders [2, 20]. It must be noted here that our use of lifetime diagnoses precludes conclusions based on the temporal order of the various forms of psychopathologies. Future studies could examine whether multimorbidity equally predicts the onset of non-affective psychosis or bipolar disorder, which would further strengthen the argument for combining these categories.

A corollary of these results is that bipolar I disorder and NAP occurred mainly in conjunction with high levels of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. With regard to bipolar I disorder, this result also emerged in LCA models of the NCS-R dataset utilizing 12-month (as opposed to lifetime) diagnoses [21]. This prior study by Kessler et al. also reported a 7-class solution in their LCA analyses. However, some notable points of difference between the current study and the prior one are (a) the use of different datasets – NCS in the current study vs. NCS-R in their study, (b) the use of different time-referents (lifetime diagnoses in the current study vs. 12-month diagnoses in the prior one, and lastly, (c) the use of additional diagnoses in their study including oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder, and the lack of the non-affective psychosis diagnosis. These various points of difference between the two studies quite likely account for the differing LCA results. Nonetheless, results from Kessler et al. also show evidence for classes dominated primarily by fear, distress, or externalizing disorders, and two classes that appear to be multimorbid and have the highest prevalences of manic and hypomanic episodes, suggesting similarity among the two sets of results as well.

While no clear explanation exists for the presence of the multimorbid class, this result brings to mind an interesting suggestion put forth by Jaspers [22], and reiterated recently by Maj [23] – namely, that the nature of psychopathology might be heterogeneous, with some disorders (e.g., anxiety syndromes) lying on a continuum with normalcy, and others such as bipolar I disorder and NAP possibly blending with each other and with other forms of psychopathology, but not necessarily with normalcy. In support of this idea, a visual comparison suggests that the profiles of the fear, distress, and externalizing classes run somewhat parallel with the few disorders class. For example, in Figure 1, under the “Internalizing Disorders”, the prevalences of the gray bars (fear class) and green bars (distress class) appear parallel to the light blue bars (few disorder class) suggesting that these two classes may represent extremes on the fear and distress dimensions respectively. An alternative intriguing explanation might be that bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are part of a spectrum of neurodevelopmental impairment ranging from bipolar disorder to schizophrenia at one end, to autism and mental retardation at the other [24]. Clearly, however, further research is required to clarify the nature of relations between these various forms of psychopathology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants MH 65137, MH 072850, and MH 089727 (Patrick), and grants DA 024417, DA 13240, and DA 05147 (Iacono) from the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Uma Vaidyanathan, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, 75 East River Road, Minneapolis, MN 55455. Phone: 612-625-2818. Fax: 612-626-2079. vaidy017@umn.edu.

Christopher J. Patrick, Department of Psychology, Florida State University, 1107 W. Call Street, Tallahassee, FL 32306..

William G. Iacono, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, 75 East River Road, Minneapolis, MN 55455..

References

- 1.Craddock N, Owen MJ. The beginning of the end for the kraepelinian dichotomy. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:364–366. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg DP, Andrews G, Hobbs MJ. Where should bipolar disorder appear in the meta-structure? Psychol Med. 2009;39:2071–2081. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vollebergh WAM, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The nemesis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotov R, Chang S-W, Fochtmann LJ, Mojtabai R, Carlson GA, Sedler MJ, Bromet EJ. Schizophrenia in the internalizing-externalizing framework: A third dimension? Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markon KE. Modeling psychopathology structure: A symptom-level analysis of axis i and ii disorders. Psychol Med. 2010;40:273–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaidyanathan U, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Patterns of comorbidity among mental disorders: A person-centered approach. Compr Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craddock N, Owen MJ. Rethinking psychosis: The disadvantages of a dichotomous classification now outweigh the advantages. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:84–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of dsm-iii-r psychiatric disorders in the united states: Results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews G, Goldberg DP, Krueger RF, Carpenter WT, Hyman SE, Sachdev P, Pine DS. Exploring the feasibility of a meta-structure for dsm-v and icd-11: Could it improve utility and validity? Psychol Med. 2009;39:1993–2000. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of dsm-iii-r bipolar i disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1079–1089. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Technical guide to latent gold 4.5. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradshaw CP, Buckley JA, Ialongo NS. School-based service utilization among urban children with early onset educational and mental health problems: The squeaky wheel phenomenon. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman LA. Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika. 1974;61:215–231. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IRH, Gagnon E, Guyer M, Howes MJ, Kendler KS, Shi L, Walters E, Wu EQ. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the national comorbidity survey replication (ncs-r) Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a us community sample: The national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1022–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpenter WT, Bustillo JR, Thaker GK, van Os J, Krueger RF, Green MJ. The psychoses: Cluster 3 of the proposed meta-structure for dsm-v and icd-11. Psychol Med. 2009;39:2025–2042. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month dsm-iv disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaspers K. Allgemeine psychopathologie. Berlin: Springer; 1913. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maj M. 'Psychiatric comorbidity': An artefact of current diagnostic systems? The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:182–184. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.3.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC, Thapar A, Craddock N. Neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;198:173–175. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]