Abstract

Increasing availability of individual genomic information suggests that patients will need knowledge about genome sequencing to make informed decisions, but prior research is limited. In this study, we examined genome sequencing knowledge before and after informed consent among 311 participants enrolled in the ClinSeq™ sequencing study. An exploratory factor analysis of knowledge items yielded two factors (sequencing limitations knowledge; sequencing benefits knowledge). In multivariable analysis, high pre-consent sequencing limitations knowledge scores were significantly related to education (OR: 8.7, 95% CI: 2.45, 31.10 for postgraduate education and OR: 3.9; 95% CI: 1.05, 14.61 for college degree compared to less than college degree) and race/ethnicity (OR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.09, 5.38 for non-Hispanic whites compared to other racial/ethnic groups). Mean values increased significantly between pre- and post-consent for the sequencing limitations knowledge subscale (6.9 to 7.7, p<0.0001) and sequencing benefits knowledge subscale (7.0 to 7.5, p<0.0001); increase in knowledge did not differ by sociodemographic characteristics. This study highlights gaps in genome sequencing knowledge, and underscores the need to target educational efforts toward participants with less education or from minority racial/ethnic groups. The informed consent process improved genome sequencing knowledge. Future studies could examine how genome sequencing knowledge influences informed decision making.

Keywords: genomic knowledge, genome sequencing, informed consent, knowledge

INTRODUCTION

Advances in genetics and sequencing technologies have the potential to dramatically alter health care using individual patient genomic information (1–5). Sequencing of entire cancer genomes is now possible (6,7), and sequencing will likely become an important part of the clinical evaluation and management of patients (8,9). The increasing importance of this genomic information suggests that patients will need knowledge about genome sequencing to make informed decisions (10,11), both decisions related to uptake of sequencing and to disease management choices that may be based on sequencing results. The active participation of patients in decision making will necessitate some knowledge about concepts and familiarity with terminology related to genome sequencing. However, research examining knowledge about genome sequencing in the general public is scarce.

Previous research on general genetic knowledge has shown substantial gaps in understanding among the public. Much of the research has focused on assessing understanding of specific genetic tests amongst at-risk populations (10,12). However, recent research has examined genetic knowledge in the public in a number of different countries (13–15). Qualitative studies have shown that a sizable proportion of the population may not have a basic understanding of human genetic concepts (16), and that even individuals who are familiar with genetics terms may not understand the underlying concepts (16,17). Focus groups conducted with 55 patients in diverse, underserved US communities showed that participants had limited understanding of genetics or genetic testing (11). The results from survey research have supported these observations. Survey research conducted in Finland has shown that while respondents may understand general concepts related to the association of gene variants to disease, details and specialized genetics terminology are less known (10). Similarly, a survey of 1,009 adults in Western Australia found that there was greater familiarity with basic genetic concepts than understanding of the meaning of these concepts (13). A recent review of this literature found that heredity, rather than molecular genetics concepts, is the strongest component of public understanding of genetics (14). Thus, prior research suggests that individuals likely have limited knowledge related to genome sequencing, a topic based on molecular genetics concepts, and highlights the need to investigate this important question.

This study was designed to examine knowledge about genome sequencing among participants enrolled in a sequencing study. ClinSeq™ is a clinical study at the National Institutes of Health that aims to enroll a cohort of >1,000 participants who consent to whole genome sequencing and have a choice about what types of information they would like returned to them (2). We investigated the knowledge of genome sequencing among ClinSeq™ participants before and after completing the study consent process. We hypothesized that participants would have gaps in their genome sequencing knowledge prior to the consent process and that knowledge would significantly improve following the consent process. These results will inform our understanding of genome sequencing knowledge among participants enrolling in early sequencing studies. This information is critical to ensuring that participants can engage fully in decision making about return of results from genome sequencing and any subsequent treatment decision making based upon those results.

METHODS

Study design

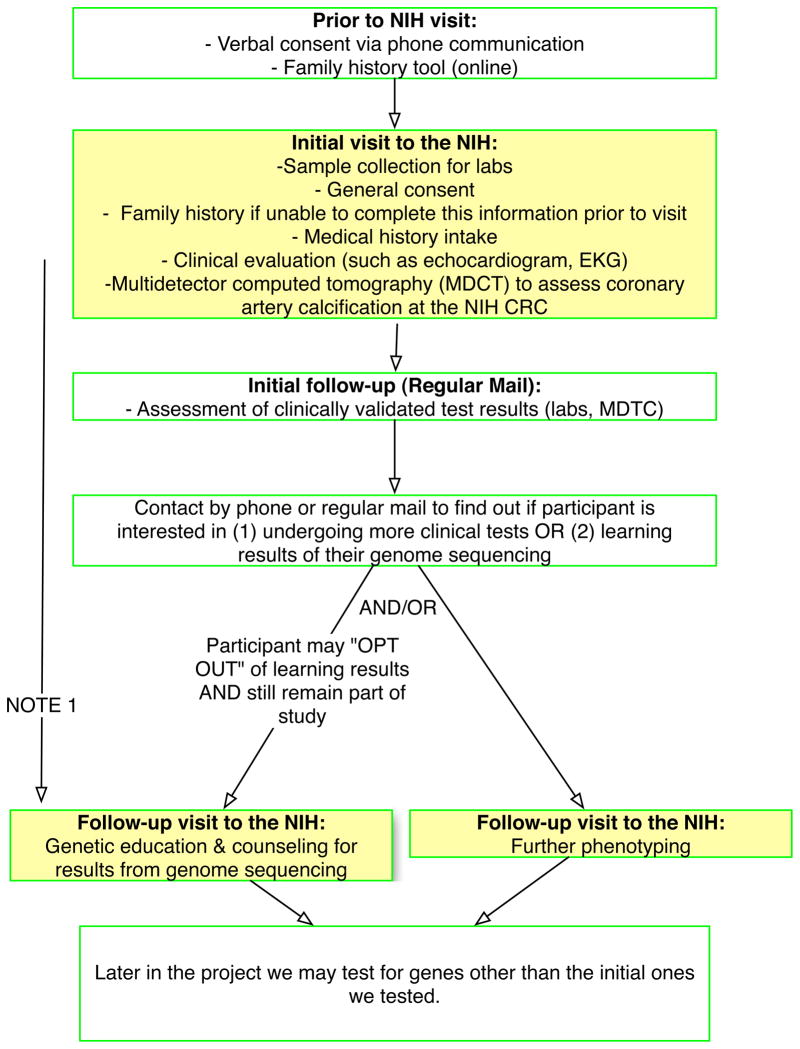

A detailed description of the ClinSeq™ cohort and study design has been published previously (2); the study design is summarized in Figure 1. In brief, the goal of ClinSeq™ is to sequence most or all regions of 1,000 human genomes. The initial focus of the study was on atherosclerotic heart disease but a majority of participants are healthy volunteers, stratified by their risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) based on the Framingham risk score. Participants in ClinSeq™ were recruited through various means, including advertisements in local papers, a cardiac rehabilitation program at a local hospital, a lipid clinic at the National Institutes of Health, and “word of mouth” through other participants. All participants were consented for interrogation of all genes and all phenotypes. The Institutional Review Board of the National Human Genome Research Institute approved this study.

Figure 1.

Design of ClinSeq™ study.

NOTE 1: The return of mutations of immediate clinical implication will take place during a face-to-face appointment at the NIH Clinical Research Center. These results will be few in number.

NOTE 2: Yellow boxes indicate steps that will take place at the NIH Clinical Research Center.

During the ClinSeq™ initial visit, participants completed a baseline survey, which assessed their knowledge about genome sequencing and their attitudes and intentions toward receiving genotype results from genome sequencing. Participants then completed an informed consent discussion with a genetic counselor, followed by a second survey of the same variables that day. Information considered central to informed consent was reviewed in a systematic way with every participant. Standardized information delivered in the session included description of genome sequencing, type of results that could be generated, choice to receive individual results over time, limitations in interpreting data, lack of reporting of un-interpretable information, and length of time before receiving results. Because individual participants could ask questions, the length of the session varied from 60–90 minutes. The genetic counselor did not review participants’ survey answers prior to the session. This analysis focused on pre- and post-consent knowledge about genome sequencing among 311 individuals sequentially enrolled in ClinSeq™ from January 2009 to May 2011.

Measures

Knowledge about genome sequencing

Because of the lack of validated knowledge scales focused on genome sequencing, we created eleven items to assess participants’ knowledge based on review of existing genetic knowledge indices (18–20) by a team of genetic communication, genetic counseling, and clinical genetics experts. Items included “Genome sequencing may find variants in a person’s genes that will increase their chance of developing a disease in their lifetime” and “Even if a person has a variant in a gene that affects their risk of a disease, they may not develop that disease” (see Appendix A). Participants responded to these items on five-point Likert scales ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. We opted for this approach instead of a true/false approach in order to be able to examine participants’ uncertainty about their responses. Four negatively worded items were reverse scored so that “strongly agree” reflected a correct response and “somewhat agree” reflected a less confident response in the correct direction for all items. To create knowledge scale scores, responses of “strongly agree” were assigned a value of 2 and “somewhat agree” a value of 1.

Appendix A.

Full text of genome sequencing knowledge items.

| Sequencing limitations knowledge subscale |

| Once a variant in a gene that affects a person’s risk of a disease is found, that disease can always be prevented or cured.* |

| A health care provider can tell a person their exact chance of developing a disease based on the results from genome sequencing.* |

| Scientists know how all variants of genes will affect a person’s chances of developing diseases.* |

| Even if a person has a variant in a gene that affects their risk of a disease, they may not develop that disease. |

| Genome sequencing is a routine test that most people can have through their physician’s office.* |

| Sequencing benefits knowledge subscale |

| Genome sequencing may find variants in a person’s genes that they can pass on to their children. |

| Genome sequencing may give a person information about their chances of developing several different diseases. |

| Genome sequencing may find variants in a person’s genes that will increase their chance of developing a disease in their lifetime. |

| Genome sequencing may find variants in a person’s genes that will decrease their chance of developing a disease in their lifetime. |

| Genome sequencing may find variants in a person’s genes that may determine how they respond to certain medicines. |

| Additional item |

| A person’s health habits, like diet and exercise, can affect whether or not their genes cause diseases. |

Note: These negatively worded items were reverse scored so that “strongly agree” reflected a correct response and “somewhat agree” reflected a less confident response in the correct direction for all items.

Participant characteristics

We recorded respondents’ age, gender, educational attainment, household income, and race and ethnicity. We also assessed whether participants had a diagnosis of CAD or their CAD risk (i.e., <5% risk; 5–10% risk; >10% risk).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were examined for all knowledge items. We then conducted an exploratory factor analysis using a varimax rotation to examine domains of genome sequencing knowledge and to obtain a limited number of subscales. We decided on the number of factors based on the criteria of having an eigenvalue of ≥ 1.0 (21). Items that did not have a factor loading of at least 0.40 on any factor were excluded. Subscale scores were created for the two identified factors by summing item scores.

We then conducted bivariate analyses to examine the associations of the pre-consent genome sequencing knowledge subscale scores to participant characteristics using chi-squared tests. We also built multivariable logistic regression models to examine whether participant characteristics predicted pre-consent knowledge subscale scores. For these models, high knowledge was defined as a subscale score of 10. Participant characteristics tested were age (dichotomized at age 55); gender (male/female); educational attainment (less than college/college graduate/postgraduate); household income (dichotomized at $100,000); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. others); and CAD status (<5% risk/5–10% risk/>10% risk/CAD diagnosis). We also examined change in knowledge subscale score between pre- and post-consent (possible range 0–10) using McNemar’s tests, and whether participant characteristics predicted change in knowledge between pre- and post-consent using ANOVA tests. We built multivariable linear regression models to examine whether participant characteristics predicted the outcome variable of change in knowledge between pre- and post-consent. Data were analyzed using SAS/STAT® Software Version 9.3 for Windows (Cary, NC). Statistical significance was assessed as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Exploratory factor analysis

The exploratory factor analysis yielded two factors (see Table 1). One of the two factors was related to the limitations of sequencing; the Cronbach’s alpha value for the sequencing limitations knowledge subscale pre-consent was 0.80. The other factor was comprised of items related to sequencing benefits knowledge, and at pre-consent had a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70. One item related to the effects of health behaviors on disease risk did not load onto either factor and was not included in the subscales.

Table 1.

Factor loadings from factor analysis of genome sequencing knowledge items.

| Knowledge concept | Factor 1 (Sequencing limitations knowledge)a | Factor 2 (Sequencing benefits knowledge)b |

|---|---|---|

| Once a risk-increasing variant is found, the disease cannot always be prevented or cured | 0.78 | 0.05 |

| Genome sequencing cannot tell someone their exact disease risk | 0.77 | −0.03 |

| Effects of all variants on disease risk are not known | 0.70 | −0.03 |

| People with a risk-increasing variant may not develop the disease | 0.50 | 0.27 |

| Genome sequencing is not a routine test available from physicians | 0.42 | 0.10 |

| Genome sequencing may find variants that people can pass on to their children | 0.13 | 0.63 |

| People can learn about risk for several diseases through genome sequencing. | 0.12 | 0.58 |

| Genome sequencing may find risk-increasing variants | 0.01 | 0.53 |

| Genome sequencing may find risk-decreasing variants | 0.14 | 0.44 |

| Genome sequencing may find variants that affect drug response | 0.03 | 0.42 |

| Health habits also affect disease risk | −0.04 | 0.31 |

Cronbach’s alpha value for sequencing limitations knowledge subscale pre-consent = 0.80

Cronbach’s alpha value for sequencing benefits knowledge subscale pre-consent = 0.70

Predictors of pre-consent genome sequencing knowledge

As shown in Table 2, higher participant scores on the sequencing limitations knowledge subscale before the consent process were significantly related in bivariate analysis to higher educational attainment (p<0.0001), higher household income (p=0.01), being non-Hispanic white (p=0.006), and having lower CAD risk (p=0.03). However, higher participant scores on the sequencing benefits knowledge subscale pre-consent was only marginally related to being non-Hispanic white (p=0.05).

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between pre-consent genome sequencing knowledge subscale scores and participant characteristics (N=311).

| Sequencing limitations knowledgea | Sequencing benefits knowledgea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Medium | High | p-value | Lower | Medium | High | p-value | |

| Age | 0.83 | 0.52 | ||||||

| < 56 | 38 (29.0%) | 57 (43.5%) | 36 (27.5%) | 29 (22.3%) | 85 (65.4%) | 16 (12.3%) | ||

| ≥ 56 | 52 (32.3%) | 66 (41.0%) | 43 (26.7%) | 41 (25.9%) | 93 (58.9%) | 24 (15.2%) | ||

| Gender | 0.34 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Female | 36 (28.8%) | 59 (47.2%) | 30 (24.0%) | 30 (24.4%) | 82 (66.7%) | 11 (8.9%) | ||

| Male | 54 (31.8%) | 66 (38.8%) | 50 (29.4%) | 42 (25.1%) | 96 (57.5%) | 29 (17.4%) | ||

| Education | <.0001 | 0.33 | ||||||

| Less than college | 24 (51.1%) | 19 (40.4%) | 4 (8.5%) | 10 (20.8%) | 34 (70.8%) | 4 (8.3%) | ||

| College graduate | 30 (37.0%) | 35 (43.2%) | 16 (19.8%) | 22 (27.8%) | 49 (62.0%) | 8 (10.1%) | ||

| Post-graduate | 37 (22.0%) | 71 (42.3%) | 60 (35.7%) | 40 (24.4%) | 96 (58.5%) | 28 (17.1%) | ||

| Household income | 0.01 | 0.45 | ||||||

| ≥ $100,000 | 59 (26.7%) | 100 (45.2%) | 62 (28.1%) | 51 (23.5%) | 134 (61.8%) | 32 (14.7%) | ||

| <$100,000 | 31 (45.6%) | 23 (33.8%) | 14 (20.6%) | 21 (30.9%) | 39 (57.4%) | 8 (11.8%) | ||

| Race | 0.006 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 63 (26.7%) | 104 (44.1%) | 69 (29.2%) | 51 (21.9%) | 146 (62.7%) | 36 (15.5%) | ||

| Other | 30 (46.9%) | 23 (35.9%) | 11 (17.2%) | 22 (35.5%) | 35 (56.5%) | 5 (8.1%) | ||

| CAD status | 0.03 | 0.95 | ||||||

| < 5% risk | 19 (28.7%) | 50 (51.5%) | 28 (28.9%) | 26 (26.8%) | 59 (60.8%) | 12 (12.4%) | ||

| 5–10% risk | 27 (28.7%) | 40 (42.6%) | 27 (28.7%) | 21 (22.6%) | 58 (62.4%) | 14 (15.1%) | ||

| > 10% risk | 12 (42.9%) | 9 (32.1%) | 7 (25.0%) | 5 (19.2%) | 16 (61.5%) | 5 (19.2%) | ||

| CAD diagnosis | 35 (43.2%) | 28 (34.6%) | 18 (22.2%) | 21 (26.6%) | 48 (60.8%) | 10 (13.9%) | ||

Knowledge subscale scores were categorized as lower (0–5), medium (6–9), high (10)

In a multivariable model (see Table 3), participants who were college graduates were 3.9 times as likely to have high pre-consent sequencing limitations knowledge as those with less than a college degree (95% confidence interval: 1.05, 14.61), and participants who had post-graduate education were 8.7 times as likely to have high sequencing limitations knowledge as participants with less than a college degree (95% confidence interval: 2.45, 31.10). Race/ethnicity was also a significant predictor in this multivariable model, with non-Hispanic whites being 2.4 times as likely to have high pre-consent sequencing limitations knowledge than participants from other racial and ethnic groups (95% confidence interval: 1.09, 5.38). This model had a significant overall model effect (Wald χ2 19.92, df9, p=0.02). In a second multivariable logistic regression model, males were 2.4 times as likely to have high pre-consent sequencing benefits knowledge than females (95% confidence interval: 1.06, 5.51). However, this model did not have a significant overall model effect (Wald χ2 11.20, df9, p=0.26).

Table 3.

Predictors of high scores on genome sequencing knowledge subscales before consent in multivariable logistic regression models (N=311).

| Sequencing limitations knowledgea | Sequencing benefits knowledgeb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

| Age ≥ 56 | 0.81 | (0.44, 1.48) | 0.48 | 1.30 | (0.16, 2.76) | 0.49 |

| Male | 1.33 | (0.70, 2.50) | 0.38 | 2.41 | (1.06, 5.51) | 0.04 |

| Educational attainmentc | ||||||

| College graduate | 3.92 | (1.05, 14.61) | 0.04 | 1.29 | (0.36, 4.69) | 0.70 |

| Post-graduate | 8.73 | (2.45, 31.10) | 0.0008 | 2.34 | (0.72, 7.59) | 0.16 |

| Household income ≥ $100,000 | 0.73 | (0.34, 1.55) | 0.41 | 0.77 | (0.31, 1.95) | 0.58 |

| Non-Hispanic whited | 2.42 | (1.09, 5.38) | 0.03 | 2.54 | (0.84, 7.65) | 0.10 |

| CAD statuse | ||||||

| 5–10% risk | 1.02 | (0.50, 2.08) | 0.96 | 1.01 | (0.41, 2.47) | 0.98 |

| > 10% risk | 1.20 | (0.38, 3.74) | 0.76 | 0.95 | (0.25, 3.70) | 0.94 |

| CAD diagnosis | 0.67 | (0.28, 1.57) | 0.35 | 0.58 | (0.20, 1.67) | 0.31 |

Model Wald χ2 19.92, df9, p=0.02

Model Wald χ2 11.20, df9, p=0.26

Compared to less than college

Compared to other racial/ethnic groups

Compared to CAD risk of < 5%

Changes in knowledge before and after consent

Knowledge improved significantly between the pre-consent and post-consent surveys for ten of the eleven knowledge items (see Table 4). The one item for which knowledge did not improve (i.e., “Genome sequencing may find variants in a person’s genes that they can pass on to their children”) had the highest proportion of correct answers at pre-consent (83.2%), with a slight increase to 85.8% at post-consent. Mean values increased significantly between pre- and post-consent for both the sequencing limitations knowledge subscale (from 6.9 to 7.7, p<0.0001) and sequencing benefits knowledge subscale (from 7.0 to 7.5, p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Proportion of participants who strongly agreed to each genome sequencing knowledge item before and after consent process (N=311).

| Knowledge concept | Pre-consenta | Post-consent | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Sequencing limitations | |||||

| Once a risk-increasing variant is found, the disease cannot always be prevented or cured | 163 | (53.8%) | 191 | (67.0%) | <.0001 |

| Genome sequencing cannot tell someone their exact disease risk | 158 | (52.1%) | 184 | (64.1%) | <.0001 |

| Effects of all variants on disease risk are not known | 166 | (54.6%) | 187 | (65.2%) | <.0001 |

| People with a risk-increasing variant may not develop the disease | 166 | (54.6%) | 186 | (65.0%) | 0.001 |

| Genome sequencing is not a routine test available from physicians | 200 | (65.8%) | 206 | (71.8%) | 0.03 |

| Sequencing benefits | |||||

| Genome sequencing may find variants that people can pass on to their children | 253 | (83.2%) | 247 | (85.8%) | 0.21 |

| People can learn about risk for several diseases through genome sequencing. | 191 | (62.8%) | 220 | (76.9%) | <.0001 |

| Genome sequencing may find risk-increasing variants | 220 | (72.1%) | 231 | (80.2%) | 0.006 |

| Genome sequencing may find risk-decreasing variants | 66 | (22.0%) | 78 | (27.6%) | 0.02 |

| Genome sequencing may find variants that affect drug response | 86 | (28.5%) | 106 | (37.1%) | <.0001 |

| Health habits also affect disease risk | 79 | (26.2%) | 85 | (30.0%) | 0.03 |

Correct answers were defined as “strongly agree” for each item as shown in Appendix A.

Bivariate improvements in both sequencing limitations knowledge and sequencing benefits knowledge between pre- and post-consent did not differ significantly by participant characteristics (see Table 5), except that those participants with lower educational attainment had a significantly greater change in sequencing limitations knowledge subscore than those with higher educational attainment (p=0.009). However, in a multivariable model, there was no model effect of these participant characteristics on change in sequencing limitations knowledge.

Table 5.

Bivariate predictors of change in mean genome sequencing knowledge subscale scores between pre- and post-consent (N=311).

| Change in sequencing limitations knowledge subscalea | Change in sequencing benefits knowledge subscalea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | p-value | Mean (SD) | p-value | |

| Age | 0.66 | 0.18 | ||

| < 56 | 0.72 (1.52) | 0.33 (1.56) | ||

| ≥ 56 | 0.82 (1.91) | 0.58 (1.52) | ||

| Gender | 0.55 | 0.52 | ||

| Female | 0.85 (1.75) | 0.55 (1.42) | ||

| Male | 0.73 (1.74) | 0.42 (1.62) | ||

| Education | 0.009 | 0.67 | ||

| Less than college | 1.46 (2.17) | 0.41 (1.41) | ||

| College graduate | 0.91 (1.83) | 0.36 (1.58) | ||

| Post-graduate | 0.55 (1.52) | 0.54 (1.55) | ||

| Household income | 0.57 | 0.46 | ||

| ≥ $100,000 | 0.74 (1.64) | 0.46 (1.55) | ||

| <$100,000 | 0.88 (2.08) | 0.62 (1.52) | ||

| Race | 0.86 | 0.34 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.79 (1.62) | 0.42 (1.46) | ||

| Other | 0.75 (2.16) | 0.64 (1.80) | ||

| CAD status | 0.70 | 0.43 | ||

| < 5% risk | 0.71 (1.53) | 0.54 (1.45) | ||

| 5–10% risk | 0.67 (1.96) | 0.60 (1.60) | ||

| > 10% risk | 1.04 (1.67) | 0.09 (1.24) | ||

| CAD diagnosis | 0.92 (1.76) | 0.34 (1.64) | ||

Possible range 0–10

DISCUSSION

This study examined genome sequencing knowledge among participants enrolled in the ClinSeq™ sequencing study, focusing on two major domains: sequencing limitations knowledge and sequencing benefits knowledge. The data showed that participants had widely varying knowledge about various concepts prior to completing the study consent process. The item with the highest level of knowledge related to the concept of heredity, that genome sequencing can identify heritable variants. This finding is consistent with the prior literature on genetic knowledge, in which understanding of concepts related to heredity tends to be higher than that for other concepts (14). Interestingly, the proportion of participants who knew that genome sequencing could identify risk-increasing variants was much higher than the proportion of participants who knew that genome sequencing could identify risk-decreasing variants or variants related to drug response before consent. These findings suggest that efforts to educate patients regarding the full range of findings that can result from genome sequencing is needed to insure informed choice and to make decisions about return of results. While a previous analysis showed that many participants cited disease prevention as a key reason for their participation in the study (22), the present analysis showed limited knowledge that health habits also affect disease risk. Education on the roles of genes and health behaviors in affecting disease risk is needed as this technology is implemented in practice.

Even among this sample selected for their participation in a clinical sequencing study, we observed significant differences in sequencing limitations knowledge by educational attainment and race/ethnicity. The educational gradient was particularly strong; participants with postgraduate education were almost nine times as likely to have high sequencing limitations knowledge as those with less than a college degree. This finding is consistent with studies that have examined general genetic knowledge. Educational attainment has consistently been shown to be significantly associated with different measures of genetic knowledge across multiple studies conducted in different countries (10,12,13,23,24). We did not observe a relationship of sequencing limitations knowledge to age, although age has been shown to be significantly related to genetic knowledge in other studies (10,12,13,23,24). This difference may have been due to the limited age range in our sample. We also did not observe a difference in sequencing limitations knowledge by gender, income, or CAD status. Interestingly, we did not observe significant prediction of sequencing benefits knowledge by the sociodemographic factors examined. This difference in findings between the two domains of genome sequencing knowledge suggests that these domains of knowledge may have different sources, and it is possible that they affect informed decision making differently.

A number of different mechanisms have been proposed to explain differences in genetic knowledge across population subgroups. Observed differences in knowledge about genome sequencing might be due to differences in exposure to genetic information (25), or in information sources (11). Prior research has demonstrated that exposure to newspaper articles about genes and health is associated with genetic knowledge (26). Individuals with varying educational levels and from different racial and ethnic groups may obtain their information from different news sources, affecting their genome sequencing knowledge. Differences in genome sequencing knowledge could also be due to different levels of genetics education during schooling (18). Although most people have not received extensive formal education in school about this topic (27), individuals with post-graduate training may have received more genetics education than those individuals with less than a college degree. Our findings suggest that the mechanisms that affect sequencing limitations knowledge may differ from those that affect sequencing benefits knowledge.

Comparison of genome sequencing knowledge before and after the study consent process conducted by a board-certified genetic counselor demonstrated learning among participants during the consent process. Knowledge increased significantly for ten of the eleven items and for both subscales. The remaining item had high levels of pre-consent knowledge, so the lack of a significant increase may be due to a ceiling effect. This finding of improvements in knowledge is consistent with previous studies showing that genetic counseling can improve knowledge of cancer genetics (28,29). Interestingly, in this study, we did not find significant differences in improvement in genome sequencing knowledge between pre- and post-consent by educational attainment, race/ethnicity, age, gender, income, or CAD status in multivariable models. This finding suggests that the education conducted as part of the consent process was effective across subgroups. However, as genome sequencing reaches increasingly large and diverse populations, it will be important to explore whether there are more time and cost effective methods of conveying the information. Prior research has indicated that multimedia approaches may be effective in delivering some genetics education, which can supplement more focused efforts by a genetic counselor (30,31). Randomized trials of educational approaches for genome sequencing information are needed to test alternative methods of information delivery.

It will also be critical to explore in future studies whether the magnitude of gains in genome sequencing knowledge observed in this study will impact patients’ informed decision making. Although patient knowledge has been identified as a critical component in informed decision making (32–34), the domains of genome sequencing knowledge that are most important in informed decision making have not been identified. In addition to knowledge, attitudes toward genome sequencing are also critical in shaping intentions and test choice (35). Studies investigating the relationships of the different knowledge subscales and related attitudes toward genome sequencing with patients’ decision making would be valuable in informing this area of research.

This study had a number of limitations that should be considered in interpreting the results. As mentioned above, this measure of genome sequencing knowledge may not capture all aspects of this construct that are important in patients’ informed decision making. However, there is presently no consensus on the most important aspects of knowledge (10), and this is a particularly important area for the development of theory to identify knowledge domains that are important in informed decision making about genome sequencing. In future work, the test-retest reliability of the genome sequencing knowledge subscales without an educational intervention could be evaluated. The increase in genome sequencing knowledge observed between pre- and post-consent may have been due in part to testing effects, such that participants attended more to the parts of the consent process related to the pre-consent survey. The pre-consent survey may have led some participants to ask additional questions of the genetic counselor, thereby perhaps influencing learning. In addition, this population is unlikely to be generalizable to the general public, and may be more knowledgeable about or interested in genomics, but is informative in thinking about the educational needs of early adopters of genome sequencing technologies.

This study highlighted knowledge gaps related to genome sequencing in early adopters of this technology. We found that a consent process conducted by a genetic counselor could improve participants’ genome sequencing knowledge. Participants with lower educational attainment or those from racial and ethnic minority groups may have less knowledge about the limitations of genome sequencing prior to a consent process, and may need targeted educational efforts. This is likely to be particularly true as the reach of this technology expands. Future research is needed to explore the relationship between participants’ genome sequencing knowledge and informed decision making regarding uptake of the technology and medical decisions stemming from sequencing results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health. KAK was supported by funding from the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation. The authors thank the ClinSeq™ participants who completed the surveys for this analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The National Human Genome Research Institute and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation did not play a role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, report writing or decision to submit the report for publication.

References

- 1.Ng S, Turner E, Robertson P, et al. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature. 2009;461:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature08250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biesecker LG, Mullikin JC, Facio FM, et al. The ClinSeq Project: Pilot large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res. 2009;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi M, Scholl U, Ji W, et al. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19096–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910672106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roach J, Glusman G, Smit A, et al. Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2010;328:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1186802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupski J, Reid J, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing in a patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1181–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Ding L, et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The International Cancer Genome Consortium. International network of cancer genome projects. Nature. 2010;464:993–998. doi: 10.1038/nature08987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasche B, Absher D. Whole-genome sequencing: a step closer to personalized medicine. J Am Med Assoc. 2011;305(15):1596–1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jallinoja P, Aro AA. Knowledge about genes and heredity among Finns. New Genet Soc. 1999;18(1):101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catz DS, Green NS, Tobin JN, et al. Attitudes about genetics in underserved, culturally diverse populations. Commun Genet. 2005;8:161–172. doi: 10.1159/000086759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henneman L, Timmermans DRM, van der Wal G. Public experiences, knowledge and expectations about medical genetics and the use of genetic information. Commun Genet. 2004;7:33–43. doi: 10.1159/000080302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molster C, Charles T, Samanek A, O’Leary P. Australian study on public knowledge of human genetics and health. Commun Genet. 2009;12(2):84–91. doi: 10.1159/000164684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiyama I, Nagai A, Muto K, et al. Relationship between public attitudes toward genomic studies related to medicine and their level of genomic literacy in Japan. Am J Med Genet. 2008;146A:1696–1706. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haga SB, Barry W, Mills R, et al. Health literacy, genetic literacy & attitudes towards genetics. Paper presented at: American Public Health Association annual meeting; October 30, 2011; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanie AD, Jayaratne TE, Sheldon JP, et al. Exploring the public understanding of basic genetic concepts. J Genet Couns. 2004;13(4):305–320. doi: 10.1023/b:jogc.0000035524.66944.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesters I, Ausems A, De Vries H. General public’s knowledge, interest and information needs related to genetic cancer: An exploratory study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005;14:69–75. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furr LA, Kelly SE. The Genetic Knowledge Index: Developing a standard measure of genetic knowledge. Genet Testing. 1999;3(2):193–1999. doi: 10.1089/gte.1999.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Neill SC, White DB, Sanderson SC, et al. The feasibility of online genetic testing for lung cancer susceptibility: Uptake of a web-based protocol and decision outcomes. Genet Med. 2008;10:121–130. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f8e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly K, Leventhal H, Marvin M, Toppmeyer D, Baran J, Schwalb M. Cancer genetics knowledge and beliefs and receipt of results in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals receiving counseling for BRCA1/2 mutations. Cancer Control. 2004;11(4):236–244. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser H. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Facio FM, Brooks S, Loewenstein J, Green S, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Motivators for participation in a whole-genome sequencing study: implications for translational genomics research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.123. advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlsbeek H, Morren M, Bensing J, Rijken M. Knowledge and attitudes towards genetic testing: a two year follow-up study in patients with asthma, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. J Genet Couns. 2007;16(4):493–504. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose A, Peters N, Shea JA, Armstrong K. The association between knowledge and attitudes about genetic testing for cancer risk in the United States. J Health Commun. 2005;10:309–321. doi: 10.1080/10810730590950039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Benkendorf J, et al. Ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about BRCA1 testing in women at increased risk. Patient Educ Couns. 1997;32(1–2):51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parrott R, Silk K, Krieger JR, Harris T, Condit C. Behavioral health outcomes associated with religious faith and media exposure about human genetics. Health Commun. 2004;16(1):29–45. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1601_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Condit C. Public understandings of genetics and health. Clin Genet. 2010;77:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaphingst K, McBride C. Patient responses to genetic information: Studies of patients with hereditary cancer syndromes identify issues for use of genetic testing in nephrology practice. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30(2):203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lea DH, Kaphingst KA, Bowen D, Lipkus I, Hadley DW. Communicating genetic information and genetic risk: An emerging role for health educators. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14(4–5):279–289. doi: 10.1159/000294191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, et al. Use of an educational computer program before genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility: Effects on duration and content of counseling sessions. Genet Med. 2005;7(4):221–229. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000159905.13125.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, et al. Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292:442–452. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect. 2001;4(2):99–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TM. The multi-dimensional measure of informed choice: a validation study. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TM. Informed choice: understanding knowledge in the context of screening uptake. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(3):247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Facio FM, Brooks S, Eidem H, Linn A, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Intentions to receive individual genotype results from whole-genome sequencing: a survey of participants of the ClinSeq study. Eur J Human Genet. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.179. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]