Abstract

Rationale

Love has long been referred to as an addiction in literature and poetry. Scientists have often made comparisons between social attachment processes and drug addiction, and it has been suggested that the two may share a common neurobiological mechanism. Brain systems that evolved to govern attachments between parents and children, and between monogamous partners, may be the targets of drugs of abuse and serve as the basis for addiction processes.

Objectives

Here, we review research on drug addiction in parallel with research on social attachments, including parent-offspring attachments and social bonds between mating partners. This review focuses on the brain regions and neurochemicals with the greatest overlap between addiction and attachment, and in particular the mesolimbic dopamine pathway.

Results

Significant overlap exists between these two behavioral processes. In addition to conceptual overlap in symptomatology, there is a strong commonality between the two domains regarding the roles and sites of action of dopamine, opioids, and corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF). The neuropeptides oxytocin and vasopressin are hypothesized to integrate social information into attachment processes that is not present in drug addiction.

Conclusions

Social attachment may be understood as a behavioral addiction, whereby the subject becomes addicted to another individual and the cues that predict social reward. Understandings from both fields may enlighten future research on addiction and attachment processes.

Keywords: social attachment, loved, addiction, substance dependence, dopamine, opioids, CRF, oxytocin, vasopressin, pair bond

INTRODUCTION

At first, each encounter was accompanied by a rush of euphoria – new experiences, new pleasures, each more exciting than the last. Every detail became associated with those intense feelings: places, times, objects, faces. Other interests suddenly became less important, as more time was spent pursuing the next joyful encounter. Gradually, the euphoria during these encounters waned, replaced imperceptibly by feelings of contentment, calm, and happiness. The moments between encounters seemed to grow longer, even as they stayed the same; and separation came to be filled with painful longing and desire. When everything was brought to an abrupt end, desperation and grief followed, leading slowly into depression.

Is this story describing falling in love, or becoming addicted to a drug? Love is often described as an addiction, a subtle and poetic metaphor that contains seeds of truth. When we are in love, we are inundated with sensations of our beloved: the face, the eyes, the sound of the voice, the smell of cologne or perfume, and the feel of the skin. These sensations are coupled with powerful experiences of social and sexual reward, and this conditioning leads them to adopt a strong positive valence. The pleasurable memories we form drive us to seek out more experiences with the beloved, and eventually, to be willing to perform incredible acts of romance and self-sacrifice.

Like those who fall in love, those who are exposed to drugs of abuse also experience powerful feelings of reward and euphoria that lead to reinforcement of drug-taking behavior. This reinforcement drives drug users to seek out more experiences with drugs, which can lead to strong addictions. Addicts are also willing to sacrifice in order to obtain and consume drugs; however, those exact same self-sacrificing behaviors that we see as romantic and laudable in the context of parental or romantic love, are seen as dangerous and self-destructive in the context of drug addiction.

These two behaviors share more than just psychological similarities. A deep and systematic concordance exists between the brain regions and neurochemicals involved in both addiction and social attachment. In this review we will address the hypothesis that love is a behavioral addiction. To do so, we will discuss the concordance and discordance between addiction and social attachment in psychiatry and in neurobiology, with a focus on those brain regions and neurochemical systems with the greatest overlap between the two. This includes primarily dopamine (DA), opioids, CRF, oxytocin (OT), and arginine vasopressin (AVP) within the mesolimbic DA pathway, a series of brain regions that govern many aspects of reward, reinforcement, and attachment. We will consider research performed largely in animal models, and in particular, extensive research conducted over decades on drug self-administration and substance dependence in rodents. Animal research will be presented alongside parallel findings in humans that demonstrate the conserved role of each neurochemical system discussed in governing human behavior.

In exploring attachment, we will discuss several animal models of social attachment that have been developed, including maternal attachment in sheep and other mammals, and the formation of selective monogamous pair bonds between mating partners in the prairie vole. Our extrapolation from animal studies of maternal attachment and pair bonding to human love relies on the supposition that these behaviors are the evolutionary antecedents of human social attachments, which we refer to as love. While this may be debated, it is likely that these behaviors in humans and animals share common underlying neurobiological mechanisms.

WHAT IS ADDICTION?

Addiction in humans

On June 18, 2009, then-Governor of South Carolina Mark Sanford, after having been dealt a major legislative loss, disappeared for 6 days (Brown and Dewan 2009). Rumors of his whereabouts abounded during this time, and the Lieutenant Governor admitted that neither he nor the governor’s family knew where the governor was. Finally, on June 24, Mark Sanford gave a rambling press conference where he admitted to having been in Argentina, having an affair with a woman named Maria.

Over the following week, the complete story slowly came out (Rutenberg 2009). He began the affair with Maria one year before, during which time he had made several secret trips to meet her. His wife had found out 5 months before, and forbid him to see her; but despite the risks to his family, his career, and multiple failed attempts to break off their relationship, he persisted in seeking her out. He was finally caught when he seemed to lose track of the amount of time he was spending with her. Mark Sanford later described the events as “a love story; a forbidden one, a tragic one.”

This story illustrates a subtle metaphor that is often used for love: that it is an addiction. Indeed, Mark Sanford seems to have displayed many characteristic addictive behaviors: stress-induced relapse, lack of regard for consequences, being unable to quit, and losing track of time. Addiction can be an incredibly powerful drive, seeming to rob individuals of their ability to make rational choices about the personal risks and rewards of their own behavior. Love, it seems, can do the same.

The DSM-IV TR defines addiction as “a maladaptive pattern of substance use, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by three (or more) of the following [criteria], occurring at any time in the same 12-month period” (American Psychiatric Association 2000). The seven DSM-IV criteria for addiction are listed in Table 1. This definition focuses entirely on drugs of abuse. Nonetheless, there is growing interest in the classification of some behavioral disorders as addictive, and commonalities between compulsive disorders and substance addiction have been identified in terms of symptomatology, neurochemistry, and adaptations in brain function (Shaffer 1999; Holden 2001; Potenza 2006; Leeman and Potenza 2012). These issues are being addressed in the development of DSM-V, where it is proposed to place compulsive gambling and internet addiction in the same category as substance addiction (American Psychiatric Association 2012).

Table 1.

DSM-IV criteria and other characteristics of substance dependence as compared to attachment.

| Substance Dependence Criteria | Analog to Social Attachment |

|---|---|

| Great deal of time spent in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from use |

Dating; parenting |

| Substance is taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended |

Sensation of “time flying” when with the partner |

| Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced |

Loss of time with friends |

| Tolerance | Transition from early euphoria to contentment |

| Withdrawal | Grief (from loss); separation anxiety when apart |

| Unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use | Sensation of not being able to stay away from the partner; failed attempt(s) to break up |

| Continued use despite knowledge of a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by use |

Physically or emotionally abusive relationships; staying with someone who “isn’t right for you” |

| Related Behaviors | |

| Stress-induced reinstatement | Consolation-seeking |

| Dependence-induced increase in drug consumption |

Increase in time spent with the romantic partner as the relationship grows |

| Withdrawal-induced anhedonia and depression | Anhedonia and depression induced by loss or separation |

Romantic attachment is rarely thought to be a pathological disorder (but see Plato and Rowe 1986; Bédier and Belloc 2004). However, when the diagnostic criteria for substance dependence are looked at side-by-side with related phenomena observable in normal human relationships, striking parallels emerge. For instance, the DSM-IV TR defines “tolerance” as “either of the following: a need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect; or markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.” In substance abuse, this manifests in increasing usage of the drug as the euphoric “high” slowly wanes and is replaced by the relief of negative affect. In romantic relationships, escalation of “dosage” has a natural upper limit, and therefore the primary mechanism of tolerance is through the gradual transition from the initial euphoric passion of an early relationship to later feelings of contentment and the relief from separation anxiety. Virtually everyone has experienced the significant dedication of time and resources necessary for dating; the sensation of losing track of time when with someone special; and the tradeoff of time with friends, family, or other activities and responsibilities that comes with a new romantic pursuit. Most people have also felt the acute pain that comes with the loss of a loved one, or with the end of a romantic relationship. The strong overlap between characteristics of substance dependence and characteristics of social attachment suggests that attachment behavior may draw on the same psychological constructs, and perhaps the same biological substrates, as dependence on drugs of abuse.

Addiction in animal research

While complete animal models of addiction are considered by some to be impossible (but see Wolffgramm and Heyne 1995; Spanagel and Holter 1999), a wide range of paradigms have been developed that model individual features of addiction behavior (Sanchis-Segura and Spanagel 2006). Many of these paradigms are referenced in this review, and we will discuss some of them briefly here.

Addiction as a behavioral phenomenon is complex and has several components or phases, including drug consumption, reinforcement learning, drug seeking, relapse, tolerance, and withdrawal (Sanchis-Segura and Spanagel 2006). The study of drug consumption or “drug-taking” behavior is almost exclusively performed using self-administration paradigms, which can be either operant (where some behavioral response leads to automatic delivery of a drug) or non-operant (as with oral consumption). This is related (but not equivalent) to the positive reinforcement provided by consumption of the drug, which is measured using a broad range of tests, including conditioned place preference; conditioned approach; and, more recently, drug-induced memory enhancement.

Drug-seeking behavior refers generally to any behavior an animal is willing to perform in order to acquire or obtain access to a drug; while this is complicated to separate from drug-taking, several paradigms exist to do this, and the most common is reinstatement of drug-seeking after extinction (de Wit and Stewart 1981). Reinstatement can occur as a result of stress, cues that predict the drug, or a dose of the drug itself, and is widely considered to be a valid model for drug-seeking and for relapse in general. More recently, paradigms have been developed to model compulsive drug-seeking despite negative consequences, which pair drug delivery with various aversive stimuli such as electric shock (Deroche-Gamonet et al 2004), bitter taste (Wolffgramm and Heyne 1995), or fear-conditioned cues (Vanderschuren and Everitt 2004). Other paradigms for testing drug-seeking include second-order self-administration, where subjects must perform a behavior in order to gain access to a device that delivers the drug (Everitt and Robbins 2000; Schindler et al 2002); or dependence-induced increases in self-administration (Rimondini et al 2002).

Tolerance refers to both physiological and behavioral adaptations that reduce the responses to drugs of abuse over the course of repeated exposure, and numerous tests exist to measure tolerance on a wide range of variables (Miller et al 1987). Conversely, withdrawal (or physical dependence) refers to maladaptations to prolonged drug use that result in negative affect or aversive responses during abstinence. It is important to note, however, that while many studies using tolerance and withdrawal as measures are cited in this review, not all researchers agree that tolerance and withdrawal represent addiction-related phenomena, despite their presence in the DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse in humans (Miller et al 1987; Volkow and Li 2005). Thus, the reader should exercise caution in interpreting the expression of tolerance or withdrawal in animals as indicative of addiction. (For a complete review of behavioral models relevant to addiction, see Sanchis-Segura and Spanagel 2006.)

DOPAMINE

DA has five different receptors in two classes. The DA D1-like receptors (including D1R and D5R) are excitatory and have a low affinity for DA, meaning they respond primarily to high DA concentrations occurring during phasic firing of dopaminergic neurons (Sibley et al 1993; Missale et al 1998; Dreyer et al 2010). The DA D2-like receptors (including D2R, D3R, and D4R) are inhibitory and have a high affinity for DA, allowing them to respond to low DA concentrations present during tonic firing. These two classes of receptors are generally expressed on separate neurons, and in the striatum, these neurons are associated with different output pathways.

Dopamine in Addiction

DA has a well-validated role in addiction processes. All known drugs of abuse cause DA release in the nucleus accumbens (NAC), preferentially in the nucleus accumbens shell region (NACs), and also more broadly throughout the mesolimbic DA pathway (Swanson 1982; Di Chiara and Imperato 1988; Koob and Bloom 1988; Pontieri et al 1995; Pontieri et al 1996; Tanda et al 1997; for a review, see Di Chiara et al 2004). DA release in the NAC is particularly important, and is correlated with human subjective ratings of drug reward and drug craving for many drugs of abuse (Volkow et al 1996a; Drevets et al 2001). However, the role of the mesolimbic DA pathway goes far beyond drug addiction – animal studies have shown that DA is released in this pathway in response to a wide variety of rewards, including sex, food, water, and intracranial self-stimulation (Cooper and Breese 1975; Hernandez and Hoebel 1988; Damsma et al 1992; Yoshida et al 1992; Young et al 1992). Though theories abound, the mesolimbic DA pathway is generally thought to be involved in both the motivation to act or work for rewards, and the salience of incentives (Mogenson 1987; Blackburn et al 1992; Ikemoto and Panksepp 1999; for a complete discussion of the many competing theories regarding the role of the mesolimbic DA pathway, see Wise 2004; Berridge 2007). These observations provide evidence for the theory that drugs of abuse activate brain systems that evolved to process natural motivation and the salience of reward-related cues (Kelley and Berridge 2002). Recent experiments also show that acute stressors are encoded by DA-releasing neurons in the VTA, cause DA sensitization in the NAC, and facilitate drug taking; demonstrating that mesolimbic DA release also encodes negative motivational states and stress responses (Miczek et al 2011; Wang and Tsien 2011).

These two classes of DA receptor also seem to have distinct roles in the response to drugs of abuse. Under normal conditions, a synergistic balance of D1R- and D2R-like activation exists in striatal regions (Walters et al 1987; LaHoste et al 1993; Gerfen et al 1995; Wise et al 1996; Hu and White 1997). Cocaine primarily activates D1R-containing neurons, which are necessary for reward-related learning and maintenance of reward-related behaviors (Nakajima 1986; Nakajima and Mckenzie 1986; Beninger et al 1987; Bertran-Gonzalez et al 2008). Chronic exposure to cocaine is associated with an increase in phasic D1R signaling, and these increases are involved in reward prediction, sensitized responses to reward, and in dampening further reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse (Ljungberg et al 1992; Henry and White 1995; Self et al 1996; Anderson et al 2008; Bertran-Gonzalez et al 2008; Zweifel et al 2009). Nonetheless, rodents will not self-administer selective D1R agonists, which, by themselves, induce conditioned place aversion (Woolverton et al 1984; Hoffman and Beninger 1988). Furthermore, if cocaine is administered with D2R-like antagonists, it loses its reinforcing effects (Woolverton and Virus 1989; Bachtell et al 2005; Claytor et al 2006; Peng et al 2009).

D2R is also necessary for reward and incentive learning, as well as maintenance of reward- and incentive-related responding, and rats will readily self-administer drugs that activate these receptors (Woolverton et al 1984; Sanger 1986; Woolverton 1986; Hoffman et al 1988; for an early review of the roles of D1R and D2R in reward and reinforcement, see Beninger et al 1989). The same chronic cocaine exposure is associated with decreases in tonic D2R signaling, and these decreases are involved in drug withdrawal, compulsive intake, and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (Nestler et al 1990; Self et al 1996; Perez et al 2011; Grieder et al 2012). PET studies show that D2R availability is decreased after long-term exposure to many different drugs of abuse (Volkow et al 1996b; Volkow et al 1997; Wang et al 1997a; Volkow et al 2001; Fehr et al 2008; reviewed in Volkow et al 2009). This same reduction in D2R is also seen in obesity, internet addiction, and trait impulsivity (Wang et al 2001; Buckholtz et al 2010; Kim et al 2011). This body of evidence suggests that a disruption in the balance of D1R- and D2R-like pathways in favor of D1R may underlie the behavioral changes seen in addiction and other impulse control disorders. Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that rats exposed to a wide range of drugs of abuse have large increases in the density of a high-affinity form of D2R, even when overall D2R availability is decreased (Seeman et al 2004; Seeman et al 2007; Briand et al 2008; Novak et al 2010), and so the functional consequence of these plastic changes in D2R remain incompletely understood. (For a review of drug-induced changes in dopamine systems, see Anderson and Pierce 2005; for a general review of addiction circuitry, see Volkow et al 2012.)

Dopamine in maternal behavior

All mammalian species exhibit maternal care of the young, and various animal models have been established to study maternal behavior and maternal attachment. Historically, rats and mice are the most widely studied model animals for maternal behavior. Most rodents are not spontaneously maternal, and naïve females will often attack or ignore pups (Wiesner and Sheard 1933). Shortly before giving birth, a strong change in motivational state occurs and females become highly interested in pups, displaying pup retrieval, licking/grooming, arched-back nursing, nesting, and maternal defense as archetypical maternal behaviors. Like humans, rodents are highly motivated to care for and protect offspring. Rat mothers will press a lever repeatedly to gain access to pups, and will cross an electrified grid in order to retrieve them (Nissen 1930; Wilsoncroft 1969). Rat mothers even prefer young pups to cocaine, indicating the power of their motivation toward maternal care (Mattson et al 2001). Nonetheless, rats and mice do not appear to be selective in their maternal care, as experienced mothers will direct maternal behavior toward any pups they encounter (Wiesner and Sheard 1933).

DA in the mesolimbic pathway also has a role in maternal behavior. DA is released naturally in the NAC of maternal rats during interactions with pups (Hansen et al 1993). This DA release in the NAC, and the subsequent activation of D1R, is both necessary for the normal expression of maternal behavior and sufficient to induce maternal behavior under conditions where it would otherwise not occur (Gaffori and Le Moal 1979; Hansen et al 1991a; Hansen et al 1991b; Keer and Stern 1999; Numan et al 2005; Stolzenberg et al 2007; Stolzenberg et al 2010; for a review, see Stolzenberg and Numan 2011). D2R also seems to be necessary for maternal behavior, though the site of action has not been determined (Silva et al 2001). Similarly, lesions that disrupt the release of DA from the VTA into the NAC, or simultaneous antagonism of D1R and D2R in the NAC, all disrupt motivated maternal behaviors such as retrieval without disrupting passive maternal behaviors such as nursing (Gaffori and Le Moal 1979; Hansen et al 1991a; Hansen et al 1991b; Keer and Stern 1999). This suggests that, similar to drugs of abuse, one role of the mesolimbic DA pathway and of accumbal DA in particular is to generate the powerful motivational states that produce such dramatic maternal behaviors (reviewed in Numan 2007; for a comprehensive treatment of the subject, see Numan and Insel 2003).

Dopamine in pair bonding

Adult attachments between mating partners are relatively rare in mammals, occurring in only 3-5% of mammalian species (Orians 1969; Kleiman 1977). This is in strong contrast to birds, where up to 90% of species are monogamous. This has been attributed, in part, to the fact that in birds, both parents can contribute equally to care and feeding of the young; while in mammals, lactation in the mother is the primary source of nutrition. Therefore, these attachments between mating partners in mammals are advantageous primarily only in harsh environments where low food availability and high predation rates make biparental care more beneficial to survival of the young. Nonetheless, monogamy has evolved independently in multiple orders of the class Mammalia, suggesting that the evolutionary precursor for monogamous bonding is present in most if not all mammals; and some have proposed that maternal attachment is that precursor (Getz and Hofmann 1986; Ross and Young 2009; for a review of the evolution of monogamy, see Freeman and Young, in press).

Because of the relative rarity of monogamy in mammals, research on these adult attachments, referred to as “pair bonds,” has focused on a very small number of species, with the preponderance of the research being performed in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Prairie voles are socially monogamous rodents indigenous to most of the Midwest United States and Canada (Tamarin 1985). In this species, mating partners form highly selective pair bonds, share a nest, coordinate care of offspring, and display high levels of affiliative behavior toward each other and their young (Thomas and Birney 1979; Getz et al 1981; Ahern et al 2011). They are also spontaneously parental, with offspring often assisting in the care of siblings (Carter and Roberts 1997). Pair bonding in prairie voles is operationally defined based on two observable behaviors: preference for the partner over the stranger in a choice test (or “partner preference”); and intense aggression toward prairie voles other than the mate (or “selective aggression”) (Williams et al 1992; Winslow et al 1993; Insel et al 1995; Wang et al 1997b; Ahern et al 2009). These two observable behavioral measures describe different dimensions of the pair bond: partner preference measures the motivational force bringing the partners together, while selective aggression measures mate-guarding and the rejection of new, potential partners (Carter et al 1995). Although mating is not required for pair bonding, prairie voles will reliably form a pair bond with a partner after 24 hours of mating, but not after 6 hours of cohabitation where mating is prevented (Wang et al 1999). These two conditions have been used extensively in the prairie vole to test pharmacological and neurological manipulations given only during the cohabitation period that either prevent or enhance the subsequent formation of pair bonds (for an early review see Carter et al 1995; more recently see Young and Wang 2004; McGraw and Young 2010).

Like with drugs of abuse, mesolimbic DA is a major contributor to the formation of pair bonds in prairie voles, and particularly in the NAC shell region. Mating has been shown to cause DA release in the NAC in rodents (Damsma et al 1992; Gingrich et al 2000). In prairie voles, pair bonding between mating partners is prevented if DA receptors in the NAC shell are non-specifically blocked (Wang et al 1999; Aragona et al 2003). Furthermore, non-specific activation of DA receptors in the NAC shell is sufficient to induce pair bonding, even if no mating occurs.

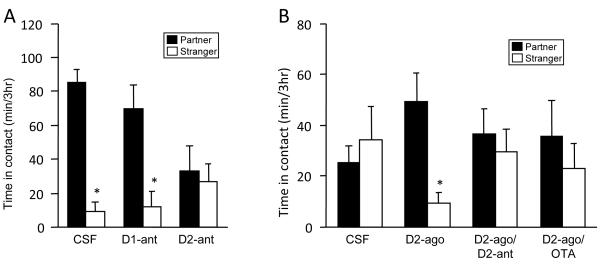

However, despite these non-specific effects, the two DA receptor types seem to play opposite roles in pair bonding (Fig. 1). Mating-induced pair bonding is prevented by selective blockade of D2R in the NAC shell, while activation of these receptors induces bonding in the absence of mating (Wang et al 1999; Gingrich et al 2000; Aragona et al 2006). Conversely, pharmacological activation of D1R prevents pair bond formation, with or without concurrent activation of D2R (Aragona et al 2006). Blockade of D1R neither enhances nor prevents pair bonding (Wang et al 1999; Aragona et al 2006; Curtis et al 2006). Furthermore, the mixed D1R and D2R agonist apomorphine enhances pair bonding when injected into the NAC shell in low doses, where it would be expected to bind preferentially to D2R; but fails to enhance pair bonding at high doses where it would be expected to bind to D1R as well (Aragona et al 2003). Finally, amphetamine injected directly into the NAC shell creates a 20-fold increase in local extracellular dopamine, which enhances pair bonding only if a D1R antagonist is also given (Curtis and Wang 2007). These results suggest that D2R activation in the NAC shell enhances, while D1R activation inhibits, pair bond formation. (For a review see Aragona and Wang 2009.) These data are consistent with human genetic association studies showing links between attachment style and polymorphisms in DA-related genes (Lakatos et al 2000 [but see Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn 2007]; Gillath et al 2008; Luijk et al 2011).

Fig. 1.

The role of DA in pair bonding. (A) Prairie voles that mate with a partner during a 24-hour cohabitation will spend more time with the partner rather than a stranger during a subsequent partner preference test, which is the operational definition of a pair bond. Prairie voles injected with either saline or a DA D1R antagonist prior to this preference test form a pair bond normally, while injection of a D2R antagonist prior to cohabitation prevents pair bonding. These antagonist effects were shown in subsequent experiments to occur in the NAC shell. (B) Prairie voles that spend 6 hours with a partner without mating do not form a pair bond with the partner. Microinjection of a D2R agonist induces the formation of a pair bond during this 6-hour cohabitation, an effect that is blocked by a D2R antagonist. An OT antagonist also blocks agonist-induced pair bonding, suggesting that concurrent activation of D2R and OTR is necessary for pair bonding. Figure adapted from Young and Wang 2004.

There is strong overlap between these findings and the literature on drug addiction. In the context of pair bonding, the aversion induced by pure pharmacological D1R activation may associate with social cues, leading to a “conditioned partner aversion” that could explain the disruption of pair bonding. Selective activation of D1R also disrupts several kinds of reward and incentive learning (Beninger et al 1989) and therefore may disrupt the learning of associations between the social reward provided by the partner, and the partner’s specific identity cues. Furthermore, cocaine seeking behavior is inhibited by pharmacological D1R activation (Self et al 1996), suggesting that this experimental activation of D1R may reduce the drive to seek out rewards. Meanwhile, activation of D2R in the NAC shell is rewarding and enhances reward-based learning (Beninger et al 1989), which aligns well with the role of D2R in pair bonding.

DA also plays a prominent role in pair bond maintenance. Sexually naïve male prairie voles are highly social and show very little aggressive behavior toward novel conspecifics (Insel et al 1995). However, when males have cohabitated with females for two weeks, they develop intense selective aggression toward male and female strangers and not toward their female partners (Insel et al 1995; Wang et al 1997b). Since this selective aggression serves, in part, to reject potential new partners, it represents an ongoing mechanism of maintenance of the pair bond (Carter et al 1995).

Over the course of 2 weeks of cohabitation, while selective aggression behavior is forming, the mesolimbic DA system in male prairie voles undergoes plastic changes (Aragona et al 2006). Expression of D1R in the NAC is 60% higher in males that cohabitate with a female than it is in males that cohabitate with a same-sex sibling; while D1R in dorsal striatum, and D2R in both areas, remains unchanged. When D1R is blocked with antagonist in the NAC shell of pair-bonded males, selective aggression toward an unfamiliar female is greatly reduced and affiliative behaviors are increased (Aragona et al 2006). These data suggest that the plastic change in D1R that occurs during pair bonding is causative in the development of selective aggression behavior, which helps to prevent the formation of a new pair bond with a new potential mate. (These topics are reviewed in Aragona and Wang 2009.) This presents an interesting contrast with literature on other types of aggression in rodents, where both D1R and D2R in the NAC play a role in aggressive behavior and in the motivation to aggress (Tidey and Miczek 1992a; Tidey and Miczek 1992b; Rodriguez-Arias et al 1998; Couppis and Kennedy 2008; reviewed in Siegel et al 1999, Miczek et al 2002); and to the treatment of aggression in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders in humans, where D2 antagonists have long been used despite the nonspecific effects on behavior in general (Yudofsky et al 1987; Buckley 1999).

There is an exceptionally strong parallel between these plastic changes from pair bonding, and the plastic changes seen in drug addiction. As D1R is upregulated during pair bonding and D2R is stable, this plastic change represents an alteration in the balance of D1R/D2R signaling in the striatum in favor of D1R, similar to what is seen in human PET studies of drug addiction (Volkow et al 2009). More directly, administering amphetamines to prairie voles daily for 3 days causes an upregulation of D1R in the NAC that mimics the upregulation seen in pair bonding (Liu et al 2010). Sexually naïve male prairie voles that receive this treatment reject potential female partners and fail to bond with them, exactly as is observed in pair-bonded males (Liu et al 2010). These same males are able to form a pair bond if D1R in the NAC shell is blocked with an antagonist, a manipulation that prevents the expression of selective aggression in drug-naïve, pair bonded males (Aragona et al 2006; Liu et al 2010). Furthermore, the changes in D1R signaling that occur during pair bonding act directly to decrease the reinforcing effects of amphetamines (Liu et al 2011). Taken together, these studies demonstrate a mechanism of cross-tolerance between pair bonding and amphetamines, which provides strong evidence that the mechanisms that govern both maintenance of social bonds (via selective aggression) and addiction to drugs of abuse (such as amphetamine) are anatomically and functionally overlapping (for a review of drugs of abuse and social behavior, see Young et al 2011b; for a comprehensive review of this section, see Young et al 2011a).

OPIOIDS

The endogenous opiate system is well-known to modulate, in part, the rewarding and reinforcing effects of food, water, sex, intracranial self-stimulation, and other rewards (Broekkamp and Phillips 1979; Turkish and Cooper 1983; West et al 1983; Agmo and Berenfeld 1990; Yeomans and Gray 1996; Gerrits et al 2003). This system is comprised of three types of opioid receptors: μ (MOR), δ (DOR), and κ (KOR); and their endogenous ligands, endorphin, enkephalin and dynorphin (Hughes et al 1975; Birdsall and Hulme 1976; Goldstein et al 1979; Evans et al 1992; Kieffer et al 1992; Chen et al 1993; Yasuda et al 1993). All three receptor types are GI protein-coupled receptors that are inhibitory when activated (Burns et al 1983; Tsunoo et al 1986; North et al 1987; for a review see Knapp et al 1995). Nonetheless, the three receptor types have different behavioral domains, with MOR and DOR mediating generally positive motivation and affect, while KOR mediates generally negative motivation and aversion (Pfeiffer et al 1986; Shippenberg et al 1987; Pecina and Berridge 2000; McLaughlin et al 2003; for reviews see Van Ree et al 2000; Le Merrer et al 2009). These three receptor types have distinct patterns of expression throughout the brain, and these patterns have significant inter-species variability (Khachaturian et al 1985; Robson et al 1985; Mansour et al 1987; Mansour et al 1988; Mansour et al 1994a; Mansour et al 1994b; Curran and Watson 1995; Resendez et al 2012).

Opioids in addiction

While opiate drugs are themselves strongly addictive, the role of the endogenous opioid system in addiction is not limited to these, as this system plays a strong role in the development of addiction to every class of drug (Altshuler et al 1980; Karras and Kane 1980; De Vry et al 1989; Kuzmin et al 1997; Ismayilova and Shoaib 2010; for a review see van Ree et al, 1999). Opioids are involved in every stage of the addiction process, including initiation, maintenance, withdrawal, and relapse (Gerrits et al 2003). Opioids also interact with other addiction-related neurochemical systems, including DA and glutamate, though these interactions do not entirely explain the role of opioids in addiction (Dichiara and Imperato 1988; Johnson and North 1992; Scavone et al 2011).

Based on animal studies, the role of opioids in the positive reinforcing effects of natural rewards and drugs of abuse has largely been attributed to MOR in the NAC, VP, and VTA, though some part is also played by DOR (van Ree and de Wied 1980; Shippenberg et al 1987; Hubner and Koob 1990; Olmstead and Franklin 1997a; Corrigall et al 2000; Pecina and Berridge 2000; Van Ree et al 2000; Gerrits et al 2003; Smith and Berridge 2005). Activation of MOR in the VTA, and DOR in the NAC, is directly rewarding in rats, producing conditioned place preferences (Goeders et al 1984; Olmstead and Franklin 1997b). Similarly, the rewarding or reinforcing value of many drugs of abuse can be blocked by MOR antagonists injected into the NAC, the VP, or the VTA (Hiroi and White 1993; Skoubis and Maidment 2003; Soderman and Unterwald 2008). Mice that lack the MOR gene do not develop place preferences or withdrawal symptoms in response to morphine (Matthes et al 1996). (For a complete review of this topic, see Le Merrer et al 2009.)

Human studies have largely corroborated the link between MOR and positive reinforcement from natural rewards and drugs of abuse. Opioid antagonists effectively reverse the effects of opiate drugs in humans (Bradberry and Raebel 1981). Furthermore, opioid antagonists are known to reduce cravings, and are now being used to treat an increasing variety of disorders including alcoholism, opioid dependence, and obesity (O’Malley et al 1992; Volpicelli et al 1992; Greenway et al 2010; Minozzi et al 2011). This link is also verified by human studies on a genetic variant of the MOR gene, A118G. The A118G variant has enhanced binding and signaling properties, but low expression of mRNA (Zhang et al 2005; Kroslak et al 2007).

Human subjects possessing this variant of the MOR gene have altered reinforcement learning and increased risk for alcohol dependence (Lee et al 2011; Koller et al 2012). Rhesus macaques also have a functionally similar variant of the MOR gene, C77G, which also results in increased alcohol intake (Barr et al 2007). Interestingly, both human A118G subjects and Rhesus C77G subjects are more likely to respond positively to opioid antagonist therapy for alcoholism, which suggests that the differences in receptor properties may be a direct physiological mechanism for the increased risk for alcoholism (Oslin et al 2003).

KOR is also involved in addiction-related processes. Drugs of abuse cause dynorphin release and up-regulation of dynorphin in the dorsal and ventral striatum, which inhibits DA release by acting on KOR receptors and is therefore thought to be compensatory (Hanson et al 1988; Sivam 1989; Spanagel et al 1990; Hurd et al 1992; Daunais et al 1993; El Daly et al 2000; Isola et al 2009). During withdrawal, this up-regulation and subsequent activation of KOR may contribute to negative affect and thus promote relapse (Przewlocka et al 1997; Simonin et al 1998; Walker and Koob 2008). As such, KOR may be a mechanism for maintenance of drug use (for a review of KOR in addiction, see Bruijnzeel 2009).

Opioids in maternal behavior

Opioids have also been implicated in the neurobiology of social reward in animals, largely by early work by Jaak Panksepp. In puppies, guinea pigs, and chicks, separation from the mother is highly stressful, and the offspring use separation-induced distress vocalizations to call to the mother. Distress vocalizations are effectively blocked by low, non-sedative doses of opioid agonists, and, in most cases, induced by opioid antagonists (Panksepp et al 1978; Warnick et al 2005). Similarly, social solicitation for attention in puppies is increased with opioid antagonists, although this same treatment reduces the comfort received from subsequent social contact (Panksepp et al 1980). Low-dose morphine also reduces social contact in guinea pigs and rats (Herman and Panksepp 1978; Panksepp et al 1979). These and other observations led to the opioid hypothesis of social attachment, which posits that opioid receptors mediate both social reward and social motivation (Herman and Panksepp 1978). According to this hypothesis, high activation of opioid receptors signals a social reward state, and low activation induces a drive to seek social rewards. Thus, opioid antagonists induce a social drive while simultaneously blocking the rewarding effects of social contact. (For a review of this literature, see Panksepp et al 1980.) This hypothesis has subsequently been supported by work on social motivation in rats and Rhesus macaques (Panksepp et al 1985; Martel et al 1993; Martel et al 1995).

Opioids also mediate many aspects of maternal behavior, and in fact, the opiate system was the first brain system to be implicated in social attachment in animals (Panksepp et al 1978). In rats, guinea pigs, sheep, and Rhesus macaques, acute administration of opioid antagonists increases social need and the solicitation for care by offspring, while agonists decrease solicitation in rats and Rhesus macaques (Panksepp et al 1980; Kalin et al 1988; Martel et al 1993; Panksepp et al 1994; Martel et al 1995; Shayit et al 2003). Studies in Rhesus macaques show similar effects of acute administration of agonists and antagonists on maternal care (Kalin et al 1995). Conversely, long-term exposure to opioid antagonists decreases maternal competence and motivation, suggesting that mothers adapt their behavior based on reduced social reward (Martel et al 1993; Martel et al 1995). Opioid agonists potentiate the formation of mother-offspring bonds and subsequent maternal behavior in sheep, while opioid antagonists prevent both mother-offspring and offspring-mother bonding (Kendrick and Keverne 1989; Keverne and Kendrick 1994; Shayit et al 2003). Some evidence also suggests that these effects may be specific to the MOR, at least with respect to infant-mother attachment. For instance, in chicks, a reduction in DVs was only observed when a MOR-selective agonist was used (Warnick et al 2005). In MOR knockout mice, pups emit fewer DVs in response to maternal separation and show less selectivity for their mothers’ cues (Moles et al 2004). (For a comprehensive discussion of this subject, see Numan and Insel 2003.)

Additionally, the same polymorphisms of the MOR gene that are associated with increased risk for alcoholism in humans and Rhesus macaques are also related to maternal behavior in both species (Barr et al 2007; Barr et al 2008; Higham et al 2011; Troisi et al 2011b). Infant Rhesus macaques possessing the C77G polymorphism of the MOR gene show increased attachment to their mothers, while Rhesus mothers possessing the same polymorphism show enhanced maternal care and higher OT release during maternal behaviors (Barr et al 2008; Higham et al 2011). Humans with the analogous A118G polymorphism are susceptible to developing fearful attachment style in response to low maternal care (Troisi et al 2011b). These studies suggest that the role of MOR in maternal behavior is conserved in humans, and also show a direct overlap between mechanisms that encode for altered attachment style and risk of alcohol dependence. (For a concise overview of these topics, see Curley 2011.)

Opioids in pair bonding

The majority of mammalian species are promiscuous breeders that do not form selective partner preferences toward specific mating partners (Kleiman 1977). Instead, when rats mate, they associate the reward from ejaculation with non-social cues and can form preferences for the location or for non-social odors (Miller and Baum 1987; Mehrara and Baum 1990; Ismail et al 2009). The formation of these non-social preferences is prevented by peripheral administration of non-selective opioid antagonists.

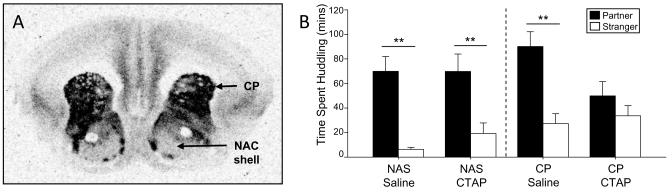

Investigations into the role of the opiate system in the formation and maintenance of pair bonds have only recently been conducted using prairie voles (Fig. 2) (Burkett et al 2011 [see also Furay and Neumaier 2011]; Resendez et al 2012). In this species, a peripherally administered, non-selective opioid antagonist prevents pair bond formation between prairie voles, but also reduces mating (Burkett et al 2011). However, a MOR-selective antagonist administered into the caudate-putamen (CP), but not the NAC shell, prevents pair bonding without affecting sexual behavior. These experiments demonstrate that MOR and the CP are necessary for pair bond formation in this species, and the roles of both seem to be conserved in humans. Individuals possessing the A118G polymorphism of the MOR gene show increased likelihood to engage in affectionate relationships, increased sensitivity to social rejection, and increased brain activity in a rejection task, possibly signaling an altered attachment style (Way et al 2009; Troisi et al 2011a). Additionally, the CP is activated in humans when viewing the faces of loved ones, and this activation is correlated with romantic love and passion scores (Bartels and Zeki 2000; Aron et al 2005; Acevedo et al 2012).

Fig. 2.

MOR and pair bonding. (A) Receptor autoradiography showing ligand binding to MOR in prairie vole brain. MOR density in the NAC shell is moderate, but much lower than MOR density in the CP. (B) After 24 hours of cohabitation with a partner, prairie voles receiving saline to the NAC shell or CP formed pair bonds as normal. MOR antagonist injected into the NAS shell did not affect pair bonding, while MOR antagonist in the CP prevented the formation of a pair bond. These data show that MOR in the CP is necessary for pair bond formation. Figure adapted from Burkett et al 2011.

A second recent study investigated the role of KOR in the maintenance of pair bonds in prairie voles (Resendez et al 2012). The authors first showed that a peripherally administered KOR antagonist, but not a MOR-preferential antagonist, prevents the expression of selective aggression in voles that have already formed pair bonds. Additionally, they localized this effect to the NAC shell, where a KOR antagonist (but not a MOR antagonist) abolished selective aggression.

These pair bonding studies reveal an interesting overlap between the opioid and DA systems. In the striatum, DA D2R is expressed in striatal neurons containing enkephalin, the endogenous ligand for MOR (Gerfen and Young 1988); both of which receptors are involved in pair bond formation but do not have a clear role in maintenance. Conversely, D1R is expressed in striatal neurons containing dynorphin, the endogenous ligand for KOR; and both of these receptors are necessary for pair bond maintenance, but not for formation. This suggests that the two receptor systems are acting in a coordinated fashion in the striatum to modulate different aspects of pair bonding (Resendez et al 2012). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the relationships between MOR and reward/formation, and between KOR and maintenance, are the same as in drug addiction.

CRF

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), sometimes called corticotropin-releasing hormone, is part of a family of proteins consisting of four endogenous ligands: CRF, urocortin-1, urocortin-2, and urocortin-3; and two receptors, CRF-R1 and CRF-R2 (reviewed in Bale and Vale 2004). This CRF system coordinates stress responding on several levels, including behavior, autonomic response, and the HPA axis. Administration of CRF into the brain of rats reproduces many different behavioral responses analogous to stress, while CRF antagonists reduce or prevent stress responses (Dunn and Berridge 1990; Heinrichs et al 1994; Menzaghi et al 1994). CRF-R1 activation mediates many of these stress effects in rats, while CRF-R2 activation is alternately the same as CRF-R1, opposing CRF-R1, or ineffective in modulating stress, depending on the assay and the brain region (Ho et al 2001; Takahashi et al 2001; Valdez et al 2004; Zhao et al 2007; for a review see Heinrichs and Koob, 2004).

CRF in addiction

In drug addiction, CRF is primarily involved in withdrawal from drugs of abuse (Koob and Kreek 2007; Koob 2008). CRF production in, and release from, the amygdala is greatly potentiated during withdrawal from a variety of drugs of abuse, as well as during chronic stress (Merlo Pich et al 1995; Rodriguez de Fonseca et al 1997; Richter and Weiss 1999; Stout et al 2000; Zorrilla et al 2001; Olive et al 2002; Funk et al 2006; George et al 2007). This CRF release produces a withdrawal-induced anxiety state that is reversed by CRF-R1 antagonists (Sarnyai et al 1995; Tucci et al 2003; Knapp et al 2004; Skelton et al 2007). In turn, increased stress and withdrawal symptoms increase drug craving, generating a powerful motivation to continue use or to relapse from abstinence (Hershon 1977; Cooney et al 1997; Sinha et al 2000).

Nonselective CRF antagonists, as well as CRF-R1 antagonists, selectively block excessive consumption of several drugs of abuse in dependent rats, but not in non-dependent rats (Valdez et al 2004; Funk et al 2006; Funk et al 2007). However, a CRF-R2 agonist also blocked excessive alcohol consumption in dependent rats, suggesting opposite roles for these two receptors (Valdez et al 2004). This research shows that CRF receptors, particularly in the amygdala, are important in mediating the motivational effects of withdrawal from drugs. These data also suggest that the ability of CRF-R1 antagonists to block excessive consumption is related to the ability of these drugs to block the aversive aspects of withdrawal (Koob and Zorrilla 2010).

Using stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking, it has been demonstrated that stress causes CRF release into the VTA and NAC shell (Wang et al 2005; Chen et al 2012a), and this CRF release acts on CRF receptors to induce reinstatement (Ungless et al 2003; Wang et al 2005; Wang et al 2007; Blacktop et al 2011). Some of the stress-related effects of CRF in the NAC shell may be DA-dependent; recall that DA is also modulated by acute and chronic stressors (Miczek et al 2011; Wang and Tsien 2011; Chen et al 2012b). The sources of CRF-releasing projections into the VTA and NAC shell are currently unknown (Tagliaferro and Morales 2008). However, the research discussed above strongly implicates the extended amygdala as the source of CRF-containing neurons mediating both drug dependence and relapse. (For a complete review of this section, see Koob 2010.)

CRF in pair bonding

Being separated from loved ones for a prolonged period of time can be highly stressful in humans. We become preoccupied with thoughts of the beloved, recalling pleasant memories of when we were together or imagining the moment of reunion. We may become obsessed with ways to bring about a reunion, particularly if the separation is due to the end of a relationship. When this loss is permanent, these thoughts can be persistent and accompanied by powerful, prolonged grief and psychic pain (Prigerson et al 1995; Horowitz et al 1997). This permanent social loss can be traumatic and cause both deterioration of physical health and susceptibility to depression (Prigerson et al 1997; Ott 2003).

The prairie vole has served as an interesting model for examining the neurochemistry of social loss. In the wild, when one member of a mating pair is lost, the surviving member typically will not take on a new partner for the duration of his or her life (Getz et al 1981). Studies have shown that total social isolation in prairie voles leads to depressive-like behavior and an increase in CRF-immunoreactive neurons in the PVN (Grippo et al 2007a; Grippo et al 2007b). Of more direct relevance is the finding that 4 days of separation from a pair-bonded mate leads to increases in passive coping strategies, a type of depressive-like behavior, in male prairie voles, and that this increase does not occur in response to separation from a male sibling (Bosch et al 2009). Specifically, males separated from their partner display robust increases in immobility and hanging in the forced swim test and tail suspension tests, respectively. This depressive-like behavior is reversed by CRF-R1 or CRF-R2 antagonists injected into the cerebral ventricle. The study also showed that pair bonding induces an increase in CRF mRNA in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, a part of the extended amygdala; suggesting that this region may be the source of separation-induced CRF release, and is primed for such release during pair bond formation. These experiments provide good evidence for the theory that CRF mediates the symptoms of social loss and depression, and that this circuitry is subverted by drugs of abuse into inducing withdrawal and enhanced consumption in drug dependence. Furthermore, it may be that CRF release during separation from the partner creates an aversive, stressful state that motivates the prairie vole to return to the partner, which in turn maintains the pair bond (Bosch et al 2009).

While it is not known where in the brain CRF acts to mediate depressive-like behaviors due to social loss, literature in other rodents allows us to form a hypothesis. The NAC shell is activated during stress in rats and mice, and this same activation in mice is blocked by CRF-R1 antagonist (Pliakas et al 2001; Kreibich et al 2009). Furthermore, CRF injected into in the NAC shell induces depressive-like behavior in rats, and this effect is reversed by a CRF-R1 antagonist (Chen et al 2012b). CRF in the NAC shell can also enhance the positive motivational value and salience of incentive cues (Pecina et al 2006; Kreibich et al 2009). Taken together, these findings indicate that CRF within the NAC shell may have a role in the stress-induced increase in incentive value of cues previously associated with reward, which may complement or create its more general effect on depression in that nucleus. This suggests that CRF may act in the NAC during social loss to increase the incentive value of partner-related cues, creating a positive incentive to return to the partner. Nonetheless, this hypothesis remains to be tested in future experiments.

CRF is also involved in the formation of pair bonds. Monogamous and non-monogamous species of voles differ greatly in the distribution of CRF-R1 and CRF-R2 in the brain, even while the distribution of CRF peptide is highly conserved (Lim et al 2005; Lim et al 2006). In male prairie voles, forced swim stress or peripheral corticosterone injections both enhance the subsequent formation of pair bonds, while these treatments inhibit pair bonding in females (DeVries et al 1996). Pair bonding in males is also enhanced by activation of CRF receptors in the brain, an effect which can be localized to the NAC shell (DeVries et al 2002; Lim et al 2007). This literature also suggests that the role of CRF in pair bonding is principally focused on the NAC shell. The facilitative effects of acute stressors on male pair bonding are directly analogous to the facilitative effects of acute stressors on drug-taking behavior, a study which, interestingly, was also performed in male rodents (Miczek et al 2011).

NEUROPEPTIDES AND SOCIAL INFORMATION

DA, opioids, and CRF all mediate the processing of different aspects of reward, reinforcement, and motivated behavior. However, since attachments are normally formed to conspecifics and not to food or other natural non-social rewards, it is logical to hypothesize the existence of a mechanism or mechanisms whereby circuits that mediate both attachment and addiction integrate social information. Such mechanisms should be known to process social information, have a demonstrated role in attachment, and interact meaningfully with the reward and salience circuitry discussed previously.

OT and AVP represent two candidate systems. These two paralogous 9-amino-acid peptides are unique to mammals, though homologues exist in a wide variety of vertebrates and invertebrates (Archer 1974; van Kesteren et al 1992). Both OT and AVP are synthesized in the hypothalamus and released from the posterior pituitary into the peripheral circulation (Gainer and Wray 1994; Burbach et al 2005). In addition, both peptides are released in the brain and bind to receptors there to affect social behaviors (Buijs et al 1983; Alonso et al 1986; Loup et al 1991). OT has a single receptor (OTR) both in the periphery and in the brain. AVP has three receptors (V1aR, V1bR, and V2R); V1bR and V2R are expressed primarily in the periphery, and while V1aR and V1bR are present in the brain, V1aR is the principal receptor implicated in social processes (Gainer and Wray 1994; Burbach et al 2005; for a review of the AVP system and behavior see Caldwell et al 2008; for a review of the OT system and behavior see Ross and Young 2009).

OT is released peripherally during labor and helps to evoke uterine contractions (Burbach et al 2005). The release of OT is also induced by vaginocervical stimulation, either from birth or from copulation. OT is also released peripherally in response to nipple stimulation, which, in the context of nursing, induces the letdown of milk from the mammary glands (Christensson et al 1989). AVP is released peripherally in response to an osmotic challenge and acts in the kidney to induce the reabsorption of water, concentrating the urine (Gainer and Wray 1994).

OT in addiction

With respect to drugs of abuse, OT is best known for being released by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy), and is associated with the prosocial effects of this drug in both humans and rats (Wolff et al 2006; Thompson et al 2007; Dumont et al 2009; Thompson et al 2009). In general, OT appears to play a modulatory role in many aspects of drug addiction. Exogenous OT attenuates many of the immediate behavioral effects of drugs of abuse, including reducing drug consumption, and some of the attenuating effects of OT are localized to the NAC (Kovacs et al 1990; Sarnyai et al 1990; Sarnyai et al 1991; Qi et al 2009; Carson et al 2010a; Baracz et al 2012). This exogenous OT acts in the NAC to reduce both formation and expression of tolerance to some of the behavioral and physiological effects of drugs of abuse (Krivoy et al 1974; Van Ree and De Wied 1977; Kovacs et al 1981; Kovacs and Vanree 1985; Ibragimov et al 1987; Kovacs and Telegdy 1987; Szabo et al 1989; Sarnyai et al 1992). This may be through OT’s modulatory effects on multiple aspects of both normal and drug-induced DA neurotransmission in the NAC (Kovacs et al 1986; Szabo et al 1988; Kovacs et al 1990; Sarnyai et al 1990; Carson et al 2010b). OT also mitigates the withdrawal symptoms of morphine and alcohol, and reduces drug-primed reinstatement of responding for amphetamine (Kovacs et al 1981; Szabo et al 1988; Carson et al 2010a). (For a review of this literature, see Kovacs et al 1998; McGregor and Bowen 2012.)

In many of these studies, the effects of exogenously administered OT and OT agonists were reversed with OT antagonists in the brain, showing the specificity of the results to central OT. Nonetheless, there is a relative lack of studies showing that OT antagonists alone affect these processes (but see Kovacs et al 1987). This suggests the possibility that the baseline activity of the endogenous OT system in these paradigms is not sufficient to affect drug-related behaviors. The overlapping presence of OT receptors in regions responsible for addiction processes may have adapted to integrate a type of stimulus not present in these studies, such as social information.

OT/AVP and social information

Evidence for the involvement of OT and AVP in social information processing in the brain comes from studies on social memory. Mice exposed to a novel intruder will show robust investigation behavior that is decreased over repeated exposures in a short time, which is considered to be a result of social memory (Dantzer et al 1987). OT and AVP facilitate this kind of social memory, while OT and AVP antagonists interfere with it. Furthermore, studies in genetic knock-out (KO) mice demonstrate that these effects are specific to social memory. Mice lacking the OT gene have impaired social memory that can be recovered by OT treatment prior to the initial social encounter, demonstrating that the presence of OT at the time of the salient event is necessary and sufficient for social memory (Ferguson et al 2000; Ferguson et al 2001). Importantly, the OT KO mice display no deficits in spatial memory, non-social olfactory memory, and habituation, and can retain a social memory if the novel intruders are painted with a non-social odor (Ferguson et al 2000; author’s unpublished data). Mice with reduced AVP release in the LS, or that are lacking AVP V1aR entirely, have similarly selective deficits in social memory, and re-introduction of AVP or V1aR respectively in the LS results in rescue of social memory (Bielsky et al 2004; Bielsky et al 2005; Lukas et al 2011). Taken together, these data demonstrate a role for OT and AVP in the selective processing of social aspects of memory (for reviews, see Bielsky and Young 2004; Wacker and Ludwig 2012).

OT/AVP in social attachment

The role of OT in regulating peripheral responses critical to maternal behavior is mirrored in the brain. OT is released centrally and peripherally during birth, and centrally released OT is both necessary for the rapid onset of maternal behavior in virgin rats, and sufficient to induce it (Pedersen and Prange 1979; Fahrbach et al 1985; van Leengoed et al 1987; Borrow and Cameron 2012). Central OT is also sufficient to induce selective mother-offspring bonds in sheep (Kendrick et al 1987). The sites of action of OT in modulating maternal behavior also overlap with the mesolimbic DA pathway. The onset of maternal behavior can be prevented by injection of an OTR antagonist into the VTA (Pedersen et al 1994). Additionally, in prairie voles, the expression of spontaneous maternal behavior in virgin females is organized by developmental (and not adult) levels of OTR in the NAC shell, and is prevented by OTR antagonist injected into this region (Olazabal and Young 2006a; Ross et al 2009b; Keebaugh and Young 2011). Early expression of maternal behavior in virgin rodents is correlated with OTR density in the NAC shell, the lateral septum (LS) and parts of the extended amygdala, all regions implicated in pair bonding and in the regulation of motivated behaviors (Champagne et al 2001; Sheehan et al 2004; Olazabal and Young 2006b; Modi and Young 2011). However, OT does not appear to be necessary for the maintenance of maternal behavior in experienced females (Fahrbach et al 1985). The dual central and peripheral role for OT in the onset of maternal behavior, and particularly in the formation of mother-offspring attachments, suggests that coordinated peripheral and central OT release during labor and nursing act to induce bonding between mother and infant (Ross and Young 2009; Feldman 2012). This coordination may be, in part, through release of OT into the forebrain by axon collaterals from projections from the hypothalamus to the posterior pituitary, which may serve to synchronize central and peripheral release. This has contributed to the theory that the OT release induced by vaginocervical stimulation and nipple stimulation during human sex, acts analogous to labor and nursing, serves to induce bonding between sexual partners (Young et al 2005); and furthermore, that pair bonding is mediated by neural systems that were elaborated in evolution from circuits originally adapted for maternal behavior (Ross et al 2009a).

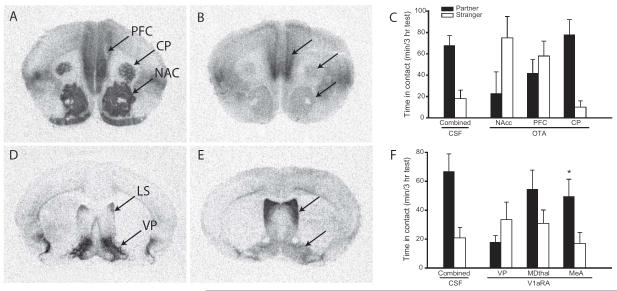

Evidence for this theory is provided by experiments demonstrating the role of OT in pair bonding between prairie voles (Fig. 3a-c). Monogamous prairie voles have significantly greater OTR density in the prefrontal cortex (the cortical component of the mesolimbic DA pathway), as CP, and NAS than do non-monogamous vole species (Insel and Shapiro 1992). OTR activation in the NAC and prefrontal cortex, but not the CP, is necessary for the formation of pair bonds in female prairie voles (Young et al 2001). In addition, OT injected into the NAC is sufficient to induce pair bonds in female prairie voles in the absence of mating, and interacts with DA D2R to do so (Liu and Wang 2003). These experiments show that OT within the mesolimbic DA pathway is essential for pair bonding in female prairie voles.

Fig. 3.

OT and AVP in pair bonding. (A) Monogamous prairie voles have high densities of OTR in the PFC, CP, and NAC. (B) By comparison, non-monogamous montane voles have relatively low densities of OTR in these regions. (C) Infusion of an OTR antagonist into the PFC and NAC of prairie voles, but not the CP, during a 24-hour cohabitation prevents the formation of pair bonds. (D) Male prairie voles have a higher density of AVP V1aR in the VP than do (E) montane voles. Infusion of a V1aR antagonist into the VP, but not into the mediodorsal thalamus (MDThal) or medial amygdala (MeA), of male prairie voles during a 24-hour cohabitation prevents the formation of pair bonds. This suggests that species differences in OTR and V1aR density in these regions may be a direct causal factor in species differences in social attachment. Figure adapted from Young and Wang 2004.

Human studies have shown the role of OT and OTR is largely conserved across species. In humans, a genetic variant of the OTR gene has been shown to correlate with pair bonding behavior in women (Walum et al 2012). OT is released in humans during hugging, touching, massage, nipple stimulation, and orgasm (Carmichael et al 1987; Christensson et al 1989; Turner et al 1999; Light et al 2000; Light et al 2005), and promotes increased eye gaze, trust, and attention to emotional cues (Kosfeld et al 2005; Domes et al 2007; Guastella et al 2008; Andari et al 2010). OT in humans is also higher during early romantic relationships, is correlated with couples’ interactive reciprocity, and predicts which couples will stay together after 6 months (Schneiderman et al 2012). These studies lend support to the hypothesis that OT release during human romantic activities serves to induce the formation of long-term bonds (Young et al 2005; Feldman 2012).

AVP also plays a role in paternal care and pair bonding in male prairie voles (Fig. 3d-f). AVP injected into the LS increases, while V1aR antagonist decreases, paternal behavior in male prairie voles (Wang et al 1994). AVP induces pair bonding in male prairie voles when injected into the LS, and V1aR antagonist in the LS or the ventral pallidum (VP) prevents pair bonding (Wang et al 1994; Lim and Young 2004). Comparative work between prairie and meadow voles has further shown that species differences in the pattern of V1aR expression are responsible for this species-typical male bonding behavior. Meadow voles are a closely related vole species that mates promiscuously without forming bonds between mating partners (Madison 1980). In male meadow voles, V1aR density in the VP is significantly lower than in prairie voles (Insel et al 1994; Young et al 1997). When these receptors are up-regulated in the VP of meadow voles to the “prairie vole-like” phenotype, these animals become capable of forming a partner preference toward a female mate (Lim et al 2004). This demonstrates that a change in the expression of a single gene in evolution can contribute significantly to species differences in highly complex social behaviors (Donaldson and Young 2008). Evidence for conservation of this role in humans was provided by a genetic study showing that males possessing one variant of the AVP V1aR gene were half as likely to be married to their partner, twice as likely to experience major relationship problems, and had partners who reported lower levels of relationship quality (Walum et al 2008).

Taken together, these data demonstrate that the OT and AVP systems have three characteristics necessary for a mechanism that integrates social information into attachment processes. Both AVP and OT are involved in social information processing and are thought to act to enhance the salience of social stimuli. Both peptides have a demonstrated role in modulating the formation of attachments. Finally, both peptides interact directly with the mesolimbic DA pathway to modulate behavior. Therefore, the OT and AVP systems are well positioned to provide social information to circuitry involved in attachment.

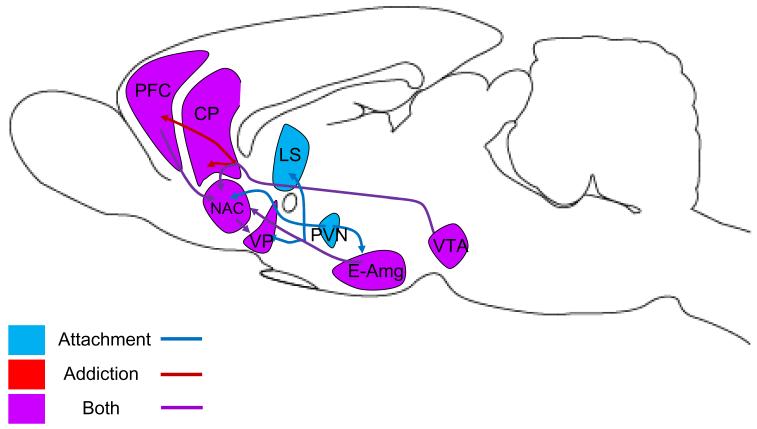

THE PARTNER ADDICTION HYPOTHESIS

The convergence of evidence from the fields of attachment and addiction reveals an inexorable series of parallels (see Fig. 4, Table 2). These parallels provide strong evidence for a link between attachment and addiction (MacLean 1990; Nelson and Panksepp 1998; Insel 2003; Fisher 2004; Reynaud et al 2010). In line with these previous authors, we propose that both attachment and addiction processes can be understood in relation to an object of addiction, whether that object is a partner (partner addiction) or a substance (substance addiction). Furthermore, the accumulation of neurochemical data now permits us to elaborate on this theory and propose a specific framework for understanding the roles of the neurochemical systems involved.

Fig. 4.

Overlapping circuits for attachment and addiction. The VTA sends dopaminergic projections to the NAC, prefrontal cortex (PFC), and CP; these projections are all implicated in addiction, while only projections to NAC are implicated in attachment. The extended amygdala (E-Amg) is the presumptive source of AVP to the VP and LS in attachment, and CRF and glutamate to the NAC in addiction and attachment. The PVN is the source of OT release in the E-Amg and NAC. Glutamatergic projections link the PFC with the NAC, and GABAergic projections link the NAC and VP.

Table 2.

Parallels between neurochemical systems involved in attachment and addiction, including DA, opioids (OP), CRF, OT, and AVP.

| Social Attachment | Maternal Attachment | Drug Addiction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FORMATION | |||

| DA | Released during mating | Released by drugs of abuse | |

| D1R inhibits bonding | D1R inhibits some aspects of drug reward, is necessary for others |

||

| D2R promotes bonding | D2R promotes drug reward | ||

| OP | Released during mating | Released by drugs of abuse | |

| MOR promotes bonding | OP promotes bonding | MOR, DOR promote drug reward |

|

| CRF | Acute stress, CRF promote male bonding |

Acute stress promotes drug taking |

|

| Acute stress inhibits female bonding |

|||

| OT | Released during mating | Released during birth, nursing |

Released by some drugs |

| OTR promotes female bonding |

OTR promotes maternal bonding |

OTR inhibits drug taking, inhibits tolerance |

|

| OTR promotes onset of maternal behavior |

|||

| AVP | V1aR promotes male bonding |

||

| MAINTENANCE | |||

| DA | Released during maternal care |

||

| D1R promotes maintenance | D1R, D2R promote maintenance |

D1R, D2R promote maintenance |

|

| Plastic changes in striatal D1R promote maintenance |

Plastic changes in striatal D2R promote maintenance |

||

| OP | Acute OP blockade promotes maintenance |

Acute OP blockade promotes maintenance |

|

| Chronic OP blockade inhibits maintenance |

Chronic OP blockade inhibits maintenance |

||

| KOR promotes maintenance | KOR promotes maintenance | ||

| Plastic changes in KOR promote maintenance |

|||

| CRF | CRF promotes maintenance | CRF-R1 promotes maintenance |

|

| CRF-R2 may inhibit maintenance |

|||

| Plastic changes in CRF promote maintenance |

Plastic changes in CRF promote maintenance |

||

| OT | OT is not necessary for maintenance |

OT is not necessary for maintenance |

OTR inhibits maintenance |

In the nascent phase of addiction, large amounts of sensory information are gathered about the object of addiction. In substance addiction, this applies to the sensory modalities appropriate for the drug: the taste and smell; the particular experience unique to the drug; and the context in which the drug is taken. With partner addiction, this information is primarily social: looks, touches, words, scents, the shape of the body and face, and possibly sexual experiences. When these early interactions with the object of addiction produce rewarding outcomes, DA is released in the NAC shell, which acts to increase the salience of incentive cues that predict the reward. Concurrent activation of D1R and D2R may represent a balance of positive and negative behavioral responses – D1R enhancing the positive incentive value of active or aggressive responses, and D2R enhancing the positive incentive value of passive, reward-related, or pro-social responses. In these addictive processes, activation of opioid receptors, and in particular MOR, occurs concurrently with experienced reward, either due to the direct effects of the substance or due to sexual contact with the partner. The opiate system interacts with the DA and OT systems to coordinate a positive response. These neurochemical systems cooperate to create a positive feedback loop where stimuli and responses coincide with reward from DA and opioids, behavior and predictive cues are positively reinforced, and positive associations accumulate.

Unlike drugs of abuse, with partner addiction, every encounter has a strong social component. Social encounters cause OT and AVP release, converging with DA in the mesolimbic DA pathway to increase the salience of social cues and information. This draws the attention of the subject to the sights, sounds, odors, unique behaviors, and other characteristics that identify the specific partner. The OT system, as an evolutionary elaboration of maternal circuitry, may promote nurturing behaviors and the identification of the partner as an object of care. The AVP system, as an evolutionary elaboration of circuitry for aggression and territoriality, may promote protective behaviors and the identification of the partner as an extension of territory (Young and Alexander 2012). Furthermore, OT may act in both types of addiction to mitigate some of the aversive or maladaptive effects of tolerance. The combined effect of these receptor systems in partner addiction is to ensure that social information and social cues become the substrates for the positive reinforcement and conditioning that occurs as a result of DA and opioids.

As the positive feedback loop continues and positive associations accumulate, adaptation occurs within the circuit in both partner and substance addiction that primes the circuitry for maintenance. The balance of DA signaling is altered in favor of D1R, leading to a progressive decrease in reward and an increase in negative affect or aggressive responses. In partner addiction, this has three principal effects. First, the early, euphoric excitement that comes with new relationships subsides, and this euphoria is gradually replaced by a more subdued sense of contentment. This first effect can be understood as tolerance to the addictive partner; tolerance to opioids may contribute to this effect as well. Second, encounters with the partner become more frequent, and the relationship may continue despite negative emotions or consequences; this can be understood as a dependence-induced escalation of consumption of the object of addiction. Opioids may also contribute here to the transition from more reward-oriented behavior toward compulsion. Finally, encounters with new potential mates continue to cause novelty-induced DA release, but now a predominance of D1R signaling promotes rejection, aggressive responses to defend the territory (including the mate), and a decrease in the probability that a second pair bond will form. In substance addiction, analogous physiological adaptations lead to drug tolerance, diminished reward, compulsive and escalating abuse, and the transition from euphoria to the relief of negative affect.

Simultaneously, CRF stress circuitry is primed for maintenance through the up-regulation of CRF peptide in the extended amygdala. This potentiated system is strongly activated during drug withdrawal and separation anxiety. This activation results in a positive motivational state driving the subject toward the object of addiction. In the case of partner addiction, this is referred to as a reunion, which can be understood as a relapse process. Upregulation of dynorphin and subsequent activation of KOR during withdrawal promotes negative affect and drives maintenance behavior. OT released during the withdrawal period may act to mitigate withdrawal symptoms and decrease the probability of relapse, which could explain both consolation-seeking behavior during break-ups, and the strong ability of social support to promote positive outcomes in drug addiction (Wills and Cleary 1996; Measelle et al 2006). When relapse is impossible, either due to loss of the partner or to continued abstinence from drug taking, the persistent anxiety state can result in prolonged negative affect and depressive-like behaviors.

Thus, addiction is created by positive reinforcement and incentive salience from DA; by reward from opioids; and, in the case of partner addiction, by enhanced salience of social cues by OT and AVP. Once the addiction is formed, it is maintained by altered DA signaling and by withdrawal-related changes in CRF and KOR signaling.

CONCLUSION

Human love is the most powerful of all emotions. When we fall in love, we experience an exquisite euphoria, loss of control, loss of time, and a powerful motivation to seek out the partner. Everything about the partner attracts us, drawing us further into an irreversible addiction. The psychology of human love and drug addiction share powerful overlaps at virtually every level of the addictive process, from initial encounters to withdrawal. A preponderance of evidence from human studies and animal models now demonstrates that these overlaps extend to the level of neurobiology as well, where virtually every neurochemical system implicated in addiction also participates in social attachment processes. These observations suggest that treatments used in one domain may be effective in the other; for instance, treatments used to reduce drug cravings may be effective in treating grief from loss of a loved one or a bad break-up (O’Malley et al 1992; Volpicelli et al 1992; Koob and Zorrilla 2010; Minozzi et al 2011). These data also provide evidence for the theory that social attachment systems governing maternal bonding and pair bonding to a mating partner are subverted by drugs of abuse to create addictions that are just as powerful as natural attachments. In a very real sense, we may be addicted to the ones we love.

Footnotes

Funding: We acknowledge funding from MH64692 to LJY, NIH RR00165 to YNPRC, and the Emory Scholars Program in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Research to JPB.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Bibliography

- Acevedo BP, Aron A, Fisher HE, Brown LL. Neural Correlates of Long-Term Intense Romantic Love. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;7:145–159. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agmo A, Berenfeld R. Reinforcing Properties of Ejaculation in the Male Rat: Role of Opioids and Dopamine. Behav Neurosci. 1990;104:177–182. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]