Abstract

Purpose

We aimed primarily to investigate the level of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and depression in older adults and secondly to identify the impact of LUTS and depression on HRQoL.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April to November 2010. Participants were recruited from five community senior centers serving community dwelling older adults in Jeju city. Data analysis was based on 171 respondents. A structured questionnaire was used to guide interviews; the data were collected including demographic characteristics, body mass index, adherence to regular exercise, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and osteoarthritis), depression, urinary incontinence, LUTS (measured via the International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS]), and HRQoL as assessed by use of the EQ-5D Index. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to test predictors of HRQoL.

Results

Eighteen percent (18.6%) of the respondents reported depressive symptoms. The mean LUTS score was 8.9 (IPSS range, 0 to 35). The severity of LUTS, was reported to be mild (score, 0 to 7) by 53% of the respondents, moderate (score, 8 to 19) by 34.5%, and severe (score, 20 to 35) by 12.5%. HRQoL was significantly predicted by depression (Partial R2=0.193, P<0.01) and LUTS (Partial R2=0.048, P=0.0047), and 24% of the variance in HRQoL was explained.

Conclusions

LUTS and depression were the principal predictors of HRQoL in older adults.

Keywords: Lower urinary tract symptoms, Depression, Quality of life, Aged

INTRODUCTION

The proportion of Koreans aged 65 years and older was 9.1% of the total population in 2005 and is forecasted to reach 14.3% in 2018 [1]. With this rapid aging of the population, urination problems of elderly people in the community have been drawing great attention [2,3]. Aging may influence lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and it is noted that both elderly men and elderly women can have LUTS [3,4]. The incidence of LUTS is defined as an International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) of ≥8, and the percentages of men and women with moderate to severe symptoms (IPSS, 8 to 35) according to age are reported to be, respectively, 30.5%, and 23.8% (in men and women aged 60 to 69 years); 40.4%, and 28.7% (in men and women aged 70 to 79 years) [4].

LUTS among the elderly can be caused not only by urologic disorders, such as benign prostatic hyperplasia, overactive bladder, and stress urinary incontinence (UI), but also by other medical conditions, such as constipation, dementia, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus, and by some drugs taken for non-urological diseases [5,6]. LUTS can have a psychological impact [7]. Wong et al. [8] reported that in 1980 elderly Chinese men aged 65 years and older, moderate to severe LUTS were significantly associated with increased odds of having clinically relevant depressive symptoms. Welch et al. [9] showed that men with moderate to severe LUTS had poorer role functioning, had less energy, and had more depressed and anxious feelings. LUTS have been shown to affect many aspects of personal lives, including social, physical, psychological, work productivity, and sexual health [10,11]. A community-based study reported that the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in more than 6,000 men was significantly worse with increasing LUTS severity [12]. The study of Okamura et al. [3] showed that the QoL of elderly Japanese men and women with LUTS decreased in the domains of role, physical and social limitations, and personal relationship.

Many factors may influence the HRQoL of the elderly. Depression, one of these factors, is also a widespread problem in elderly people, and the prevalence of depression among community-dwelling elderly is reported to be 63%; of the elderly in Korea, 21% have severe depressive symptoms [13]. Depression may worsen urination problems [8]. Most previously repoeted studies have researched the impact of LUTS on HRQoL [10,14,15]. Therefore, surveying the impact of LUTS and depression on HRQoL in the elderly may be helpful for providing proper intervention resources to improve older adults' QoL. One general tool for assessment of HRQoL, the EuroQoL EQ-5D, is an instrument that incorporates utilities or preferences for health states [16]. It has been widely used with a range of chronic health conditions [17] and LUTS severity [18].

The purposes of the present study were primarily to investigate the level of HRQoL, LUTS, and depression in older adults and secondly to identify the impacts of LUTS and depression on HRQoL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study. Data were collected from April to November 2010. Participants were recruited from five community senior centers serving community-dwelling elders in Jeju city. One hundred ninety-five (n=195) persons were eligible and agreed to participate, but 9 did not complete the interview and 15 did not respond to the EQ-5D Index questions. Therefore, the data analysis was based on 171 respondents. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Jeju National University Hospital. The principal investigator and trained research assistant visited the senior centers and explained the study purpose and data collection method. All data were collected via individual subject interviews. Interviews were completed at the community centers and took approximately 20 minutes. A structured questionnaire was used to guide the interviews; the subjects were queried about demographic characteristics (gender, age, education, living arrangements), their height and weight (these numbers were used to calculate body mass index [BMI] in kg/m2), adherence to regular exercise, and morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and osteoarthritis). Symptoms of depression were evaluated by using the Korean language version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [19], a 20-item, four-point likert scale asking how often the subject felt or behaved in the manner described within the past week. The possible score ranged from 0 (not at all depressed) to 60 (very depressed) with a threshold score of 21 as an indicator of major depressive symptoms [20]. UI was queried on the basis of the International Continence Society [21] definition (the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine). UI was operationally defined within the context of this study as a report of involuntary urine loss once per month or more frequently during the 6 months before data collection. LUTS were evaluated by use of the Korean version of the IPSS [22]. The IPSS includes 4 voiding LUTS (hesitancy, intermittency, weak stream, and incomplete emptying of the bladder) and 3 storage LUTS (frequency, urgency, and nocturia). Subjects were asked to indicate the frequency with which they experienced each of the seven symptoms during the past 6 months on a scale of 0 to 5. IPSS scores range from 0 to 35; scores ranging from 0 to 7 indicate mild LUTS, scores from 8 to 19 indicate moderate LUTS, and scores from 20 to 35 indicate severe LUTS.

HRQoL was assessed by use of the EuroQoL EQ-5D Index. The EQ-5D Index is a generic measure of health status that is widely applied in the economic evaluation of health care treatments and services. The instrument comprises a questionnaire with five dimensions: mobility (M), self-care (SC), usual activities (UA), pain/discomfort (PD), and anxiety/depression (AD). Each dimension is represented by one question with three severity levels (no problems, some or moderate problems, and extreme problems) [16,23]. The Korean version of the EQ-5D Index [24] was used in this study. Scores were transformed by using utility weights derived from the Korean general population [25,26] and ranged from -1 to 1, with higher scores indicating better overall health status. The formula producing the EQ-5D Index was as follows [26].

EQ-5D Index=1-(0.0081+0.1140×M2+0.6274×M3+0.0572×SC2+0.2073×SC3+0.0615×UA2+0.2812×UA3+0.0581×PD2+0.2353×PD3+0.0675×AD2+0.2351×AD3).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were reported by using means, standard deviations, or frequencies as indicated. In the univariate analysis, the association between the EQ-5D Index and each predictor variable was tested by using Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc test (Duncan test). In the multivariate analysis, stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the factors affecting the HRQoL (EQ-5D index) of the elderly. Variables showing statistical significance in the univariate analysis were included in the stepwise multiple regression; categorical data (gender, education level, living arrangements, BMI, regular exercise, UI, and osteoarthritis) and continuous data (depression, LUTS) were used as potential predictors of HRQoL. A P-value<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical procedures were performed by using SAS ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

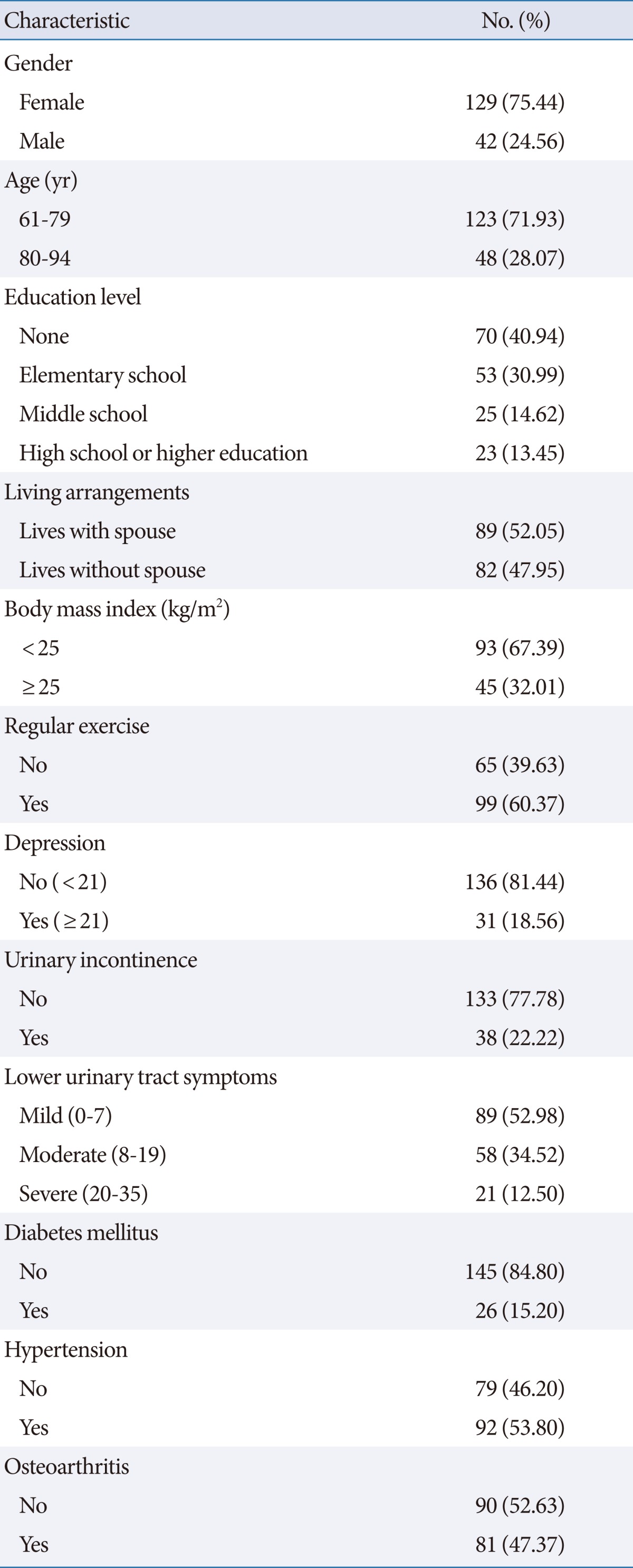

Subject Characteristics

A total of 171 older adults were enrolled in this study. Of the subjects, 75% were female. The mean age of the subjects was 76.4 years old, ranging from 6 to 94 years. By age group, 71.9% of the subjects were in the group aged 61 to 79 years and 28.1% were in the group aged over 80 years. Among the subjects, 40.9% had no formal education and 52.1% were living with a spouse. The subjects' mean BMI was 23.8 kg/m2 and 32% had a BMI≥25 kg/m2 (overweight). Regular exercise was reported by 61.4% of the subjects. Eighteen percent (18.6%) had depressive symptoms. Nearly one-quarter (22.2%) had experienced UI more than once per month during the prior 6 months. The Mean IPSS of LUTS was 8.9. Concerning the reported severity of LUTS, 53% of the subjects were in the mild group, 34.5% were in the moderate group, and 12.5% were in the severe group. Diabetes was reported by 15.2% of the subjects, hypertension by 53.8%, and osteoarthritis by 47.4% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics (n=171)a)

a)Total number of subjects does not match the number of respondents.

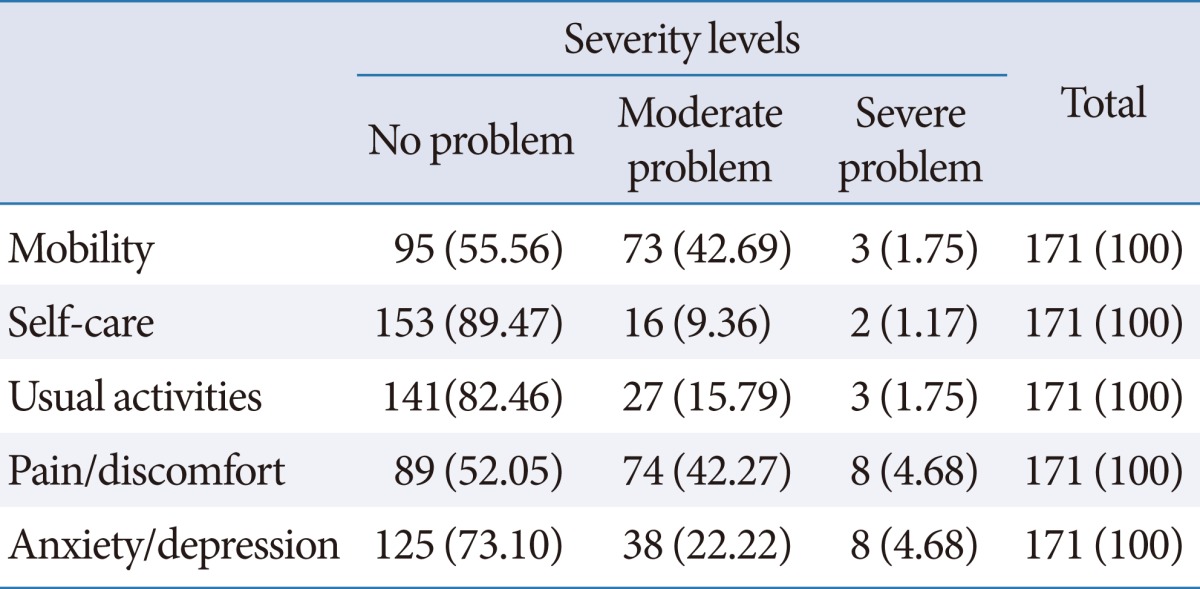

EQ-5D Index Dimensions

According to the results for severity of each the five dimensions on the EQ-5D Index, about 47% of the respondents reported moderate or severe pain/discomfort and about 45% reported moderate or severe mobility issues (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of responses to each EQ-5D Index dimension (n=171)

Values are presented as number (%).

EQ-5D Index Scores by Characteristics of Respondents

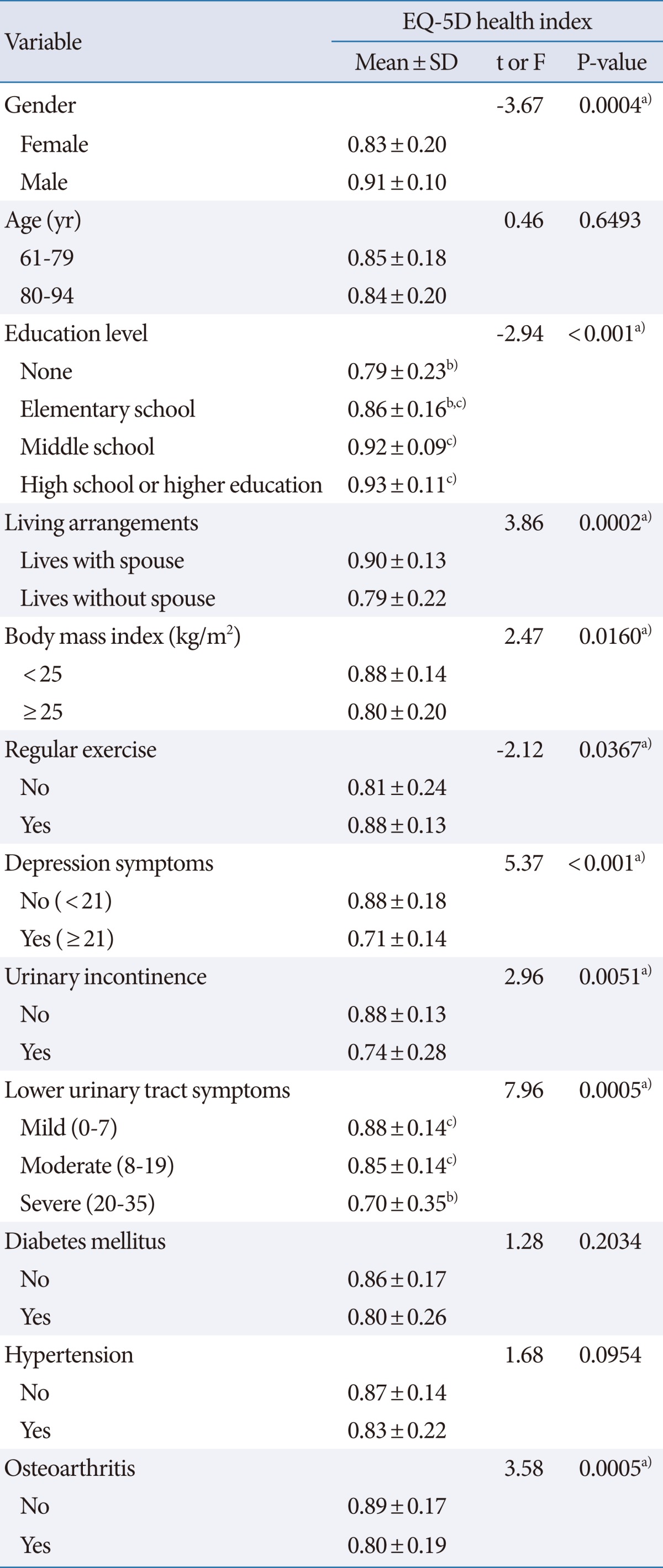

The mean EQ-5D Index score of the total respondents was 0.85±0.19 (range, -0.36 to 0.99). The EQ-5D Index was significantly different by gender (t=-3.67, P=0.0004), education level (F=-2.94, P<0.001), living arrangements (t=3.86, P=0.0002), BMI (t=2.47, P=0.0160), regular exercise (t=-2.12, P=0.0367), depression (t=5.37, P<0.001), UI (t=2.96, P=0.0051), LUTS (F=7.96, P=0.0005), and osteoarthritis (t=3.58, P=0.0005).

As shown in Table 3, the mean EQ-5D Index significantly decreased with depressive symptoms (no depression, 0.88±0.18; depression, 0.71±0.14; P<0.001) and with LUTS severity (mild, 0.88±0.14; moderate, 0.85±0.14; severe, 0.70±0.35; P=0.0005).

Table 3.

EQ-5D scores by subject characteristics (n=171)

a)Variables were analyzed via stepwise multiple regression to predict potential affecting factors for EQ-5D Index. b),c)With the superscript letters means that the results between two specified groups (between b) and c) group) are significantly different (Duncan test).

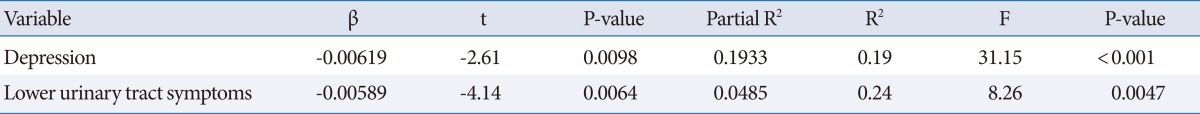

Factors Affecting HRQoL

Variables showing statistical significance in the t-test or ANOVA were investigated to test the factors affecting the EQ-5D Index. The EQ-5D Index score was significantly predicted by depression (partial R2=0.193, P<0.001) and LUTS (partial R2=0.048, P=0.0047), and 24% of the variance in the EQ-5D Index was explained (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with EQ-5D

DISCUSSION

The percentage of older adults with an IPSS of 8 and over, indicating moderate to severe LUTS, was 47%. We found that the prevalence of moderate to severe LUTS in our subjects was lower than the reported prevalence for Japanese men (72%) and women (65%) aged 50 to 92 years who visited physicians for their medical problems and higher than the 39% reported for community-dwelling Chinese men aged 65 to 90 years who were able to walk independently [8]. Shaw et al. [27] reported that one of the barriers to seeking help among people with urinary symptoms is a lack of knowledge about the condition and the treatments available. The subjects frequently considered urinary symptoms to be a normal part of aging or childbirth, or they felt that these types of symptoms were inappropriate for medical intervention. Wolters et al. [28] showed that the advice of one's social network and information from the media were clearly associated with the decision to seek primary medical care in men with LUTS. LUTS are important public health problems for older adults; therefore, media and public health education should be properly utilized for community-dwelling elderly to help them manage their LUTS and to strengthen their knowledge of LUTS.

LUTS are associated with an increased risk of having depressive symptoms [9]. This study showed that about 19% of the subjects had symptoms of depression, which was similar to the 20.1% reported in Taiwanese community-dwelling urban older adults [29]. However, further study is required to examine this relationship, because the Taiwanese study did not identify the relationship between LUTS and depression.

HRQoL is a multi-dimensional concept that encompasses the physical, emotional, and social components associated with an illness or treatment and that most commonly refers to people's experience of their global health. It may also refer to health-related subjective well-being, functional status, or self-perceived health [30]. The mean HRQoL score as measured with EQ-5D index in this cohort of community-dwelling older adults' was 0.85. This score is similar to EQ-5D index score of 0.84 for men receiving LUTS treatment in general practice and of 0.85 for adult men and women with overactive bladder [10,18], which implies that the HRQoL of our subjects was similar to the QoL of people with urinary troubles.

For the five-dimensions of the EQ-5D Index, our study showed that around half of older adults reported having unsatisfactory outcomes in the dimensions of pain/discomfort and mobility. In particular, moderate or severe problems in pain/discomfort and mobility could have a major impact on HRQoL, and problems in these two dimensions should be properly managed.

In previous studies of HRQoL and its determinants in older adults, Tajvar et al. [31] reported that elderly people's age, gender, education and economic status are significant determinants of poorer physical HRQoL. Dominick et al. [32] showed that older age, nursing home residence, and greater comorbidity were the most consistently associated with poorer HRQoL in older adults with arthritis. However, urinary problems could be one of the factors influencing HRQoL. For example, Mozes et al. [33] reported that in elderly men, severely bothersome urinary symptoms were related to scores on three QoL domains: social function, role-emotional, and mental health. The negative effect of LUTS on HRQoL, general health perception, and mental health [9] are apparent and depression is also significantly associated with decreased HRQoL [34].

Urinary problems and depression might impede independence and the ability to engage in life activities for elderly people. In the multivariate analysis in the present study, these two factors, depression and LUTS, were negatively associated with HRQoL and the explanatory factors contributed 24% to the outcome. This was similar to Quek's results [35] in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, which showed that older age, severe LUTS, and high depression scores were significantly associated with overall QoL.

The results of the present study suggest that among older adults, LUTS and depression are the principal predictors of HRQoL. The predictability of the model was not high enough, however, because it explained only 24% of the variance in HRQoL. Therefore, further study is needed to explain this phenomenon.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by a research grant from the Jeju National University.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Korean National Statistical Office. 2008 Statistics of old aged. Daejeon: Korean National Statistical Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinnock C, Marshall VR. Troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms in the community: a prevalence study. Med J Aust. 1997;167:72–75. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamura K, Usami T, Nagahama K, Maruyama S, Mizuta E. "Quality of life" assessment of urination in elderly Japanese men and women with some medical problems using International Prostate Symptom Score and King's Health Questionnaire. Eur Urol. 2002;41:411–419. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle P, Robertson C, Mazzetta C, Keech M, Hobbs FD, Fourcade R, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in men and women in four centres. The UrEpik study. BJU Int. 2003;92:409–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haidinger G, Temml C, Schatzl G, Brossner C, Roehlich M, Schmidbauer CP, et al. Risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms in elderly men. For the Prostate Study Group of the Austrian Society of Urology. Eur Urol. 2000;37:413–420. doi: 10.1159/000020162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litman HJ, Steers WD, Wei JT, Kupelian V, Link CL, McKinlay JB, et al. Relationship of lifestyle and clinical factors to lower urinary tract symptoms: results from Boston Area Community Health survey. Urology. 2007;70:916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103(Suppl 3):4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SY, Hong A, Leung J, Kwok T, Leung PC, Woo J. Lower urinary tract symptoms and depressive symptoms in elderly men. J Affect Disord. 2006;96:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch G, Weinger K, Barry MJ. Quality-of-life impact of lower urinary tract symptom severity: results from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Urology. 2002;59:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–1395. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo ES, Kim BS, Kim DY, Oh SJ, Kim JC. The impact of overactive bladder on health-related quality of life, sexual life and psychological health in Korea. Int Neurourol J. 2011;15:143–151. doi: 10.5213/inj.2011.15.3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Tsukamoto T, Richard F, Garraway WM, Sagnier PP, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in four countries. Urology. 1998;51:428–436. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JI, Choe MA, Chae YR. Prevalence and predictors of geriatric depression in community-dwelling elderly. Asian Nurs Res. 2009;3:121–129. doi: 10.1016/S1976-1317(09)60023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scarpero HM, Fiske J, Xue X, Nitti VW. American Urological Association Symptom Index for lower urinary tract symptoms in women: correlation with degree of bother and impact on quality of life. Urology. 2003;61:1118–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haltbakk J, Hanestad BR, Hunskaar S. How important are men's lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and their impact on the quality of life (QOL)? Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1733–1741. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-3232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quah JH, Luo N, Ng WY, How CH, Tay EG. Health-related quality of life is associated with diabetic complications, but not with short-term diabetic control in primary care. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2011;40:276–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fourcade RO, Lacoin F, Roupret M, Slama A, Le Fur C, Michel E, et al. Outcomes and general health-related quality of life among patients medically treated in general daily practice for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Urol. 2012;30:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0756-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho MJ, Kim KH. Diagnostic validity of the CES-D (Korean version) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1993;32:381–399. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyness JM, Conwell Y, King DA, Cox C, Caine ED. Ruminative thinking in older inpatients with major depression. J Affect Disord. 1997;46:273–277. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi HR, Chung WS, Shim BS, Kwon SW, Hong SJ, Chung BH, et al. Translation Validity and Reliability of I-PSS Korean Version. Korean J Urol. 1996;37:659–665. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam HS, Kim KY, Kwon SS, Koh KW, Poul K. EQ-5D Korean valuation study using time trade of method. Seoul: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han MA, Ryu SY, Park J, Kang MG, Park JK, Kim KS. Health-related quality of life assessment by the EuroQol-5D in some rural adults. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41:173–180. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MH, Cho YS, Uhm WS, Kim S, Bae SC. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EQ-5D in patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1401–1406. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-5681-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw C, Tansey R, Jackson C, Hyde C, Allan R. Barriers to help seeking in people with urinary symptoms. Fam Pract. 2001;18:48–52. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolters R, Wensing M, van Weel C, van der Wilt GJ, Grol RP. Lower urinary tract symptoms: social influence is more important than symptoms in seeking medical care. BJU Int. 2002;90:655–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiu HC, Chen CM, Huang CJ, Mau LW. Depressive symptoms, chronic medical conditions and functional status: a comparison of urban and rural elders in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:635–644. doi: 10.1002/gps.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revicki DA. Health-related quality of life in the evaluation of medical therapy for chronic illness. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tajvar M, Arab M, Montazeri A. Determinants of health-related quality of life in elderly in Tehran, Iran. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, Heller DA. Health-related quality of life among older adults with arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mozes B, Maor Y, Shmueli A. The competing effects of disease states on quality of life of the elderly: the case of urinary symptoms in men. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:93–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1026424911444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko Y, Coons SJ. Self-reported chronic conditions and EQ-5D index scores in the US adult population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2065–2071. doi: 10.1185/030079906x132622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quek KF. Factors affecting health-related quality of life among patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Int J Urol. 2005;12:1032–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]