Abstract

While vitamin B12 has recently been shown to co-limit the growth of coastal phytoplankton assemblages, the cycling of B-vitamins in coastal ecosystems is poorly understood as planktonic uptake rates of vitamins B1 and B12 have never been quantified in tandem in any aquatic ecosystem. The goal of this study was to establish the relationships between plankton community composition, carbon fixation, and B-vitamin assimilation in two contrasting estuarine systems. We show that, although B-vitamin concentrations were low (pM), vitamin concentrations and uptake rates were higher within a more eutrophic estuary and that vitamin B12 uptake rates were significantly correlated with rates of primary production. Eutrophic sites hosted larger bacterial and picoplankton abundances with larger carbon normalized vitamin uptake rates. Although the >2 μm phytoplankton biomass was often dominated by groups with a high incidence of vitamin auxotrophy (dinoflagellates and diatoms), picoplankton (<2 μm) were always responsible for the majority of B12-vitamin uptake. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that heterotrophic bacteria were the primary users of vitamins among the picoplankton during this study. Nutrient/vitamin amendment experiments demonstrated that, in the Summer and Fall, vitamin B12 occasionally limited or co-limited the accumulation of phytoplankton biomass together with nitrogen. Combined with prior studies, these findings suggest that picoplankton are the primary producers and users of B-vitamins in some coastal ecosystems and that rapid uptake of B-vitamins by heterotrophic bacteria may sometimes deprive larger phytoplankton of these micronutrients and thus influence phytoplankton species succession.

Keywords: phytoplankton dynamics, heterotrophic bacteria, vitamins, B12 limitation, co-limitation, vitamin to carbon ratio

Introduction

Coastal marine ecosystems are amongst the most ecologically and economically productive areas on the planet, providing an estimated US$14 trillion, or about 43% of the global total, worth in ecosystem goods and services, annually (Costanza et al., 1997). While coastal areas comprise only 8% of the world’s ocean surface they account for over 28% of the annual ocean primary production (Holligan and de Boois, 1993). In a manner paralleling global trends, nearly 75% of the US population lives within 75 km of the coastline, making these regions subject to a suite of anthropogenic influences including intense nutrient loading (de Jonge et al., 2002; Valiela, 2006) which in turn can lead to ecological perturbations such as harmful algal blooms and hypoxia (Cloern, 2001; Heisler et al., 2008). Coastal zone management efforts typically focus on minimizing total nitrogen input since primary production in most coastal marine systems are typically nitrogen-limited (Nixon, 1995). While the absolute magnitude of nitrogen entering coastal zones often controls the amount of phytoplankton biomass, the availability, and/or type (e.g., inorganic vs. organic) of nutrients can also influence the algal community composition of coastal environments (Smayda, 1997; Koch and Gobler, 2009). For example discharge from salt marsh ditches, rich in dissolved organic N, elicited a community shift in the adjacent estuarine plankton community favoring dinoflagellates over cryptophytes and cyanobacteria, likely attributable to the mixotrophic tendencies of many dinoflagellates (Taylor, 1987; Anderson et al., 2008; Burkholder et al., 2008). B-vitamins such as thiamin (B1), biotin (B7), and cobalamin (B12) are important cofactors in a number of cellular processes such as the biosynthesis of methionine (B12), the decarboxylation of pyruvic acid (B1), and fatty acid synthesis (B7). While vitamins have long been implicated as growth regulators for microalgae (Droop, 1955; Provasoli and Carlucci, 1974) their ecological importance has received little attention since early surveys (Vishniac and Riley, 1961; Menzel and Spaeth, 1962) and laboratory experiments (Droop, 1968) suggested that ambient concentration were sufficient to satisfy micro-algal demands (Swift, 1980). Newly developed methods to directly measure B-vitamins in seawater (Okbamichael and Sanudo-Wilhelmy, 2004, 2005), have facilitated surveys in several open ocean and coastal ecosystems and have revealed that vitamin concentrations are low, ranging from <0.1–40 to <0.1–100 pmol L−1 (Gobler et al., 2007; Panzeca et al., 2008, 2009; Koch et al., 2011) for B12 and B1, respectively.

Surveys of the literature as well as novel laboratory experiments indicate that over half of all phytoplankton species surveyed have an obligate requirement for an exogenous supply of one or more of the B-vitamins with B12 being required by the largest number of algae (Croft et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2010). Vitamin enrichment studies in coastal (Sanudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2006; Gobler et al., 2007) and open ocean environments (Panzeca et al., 2006; Bertrand et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2011) have shown that B-vitamins can co-limit phytoplankton biomass along with a primary limiting nutrient (i.e., nitrogen or iron). Vitamin availability can also shape coastal phytoplankton community structure. Many have argued that B12 concentrations might influence the dynamics and composition of the spring bloom (Carlucci and Bowes, 1970; Swift, 1980) since the majority of centric diatom species which comprise the spring bloom are vitamin auxotrophs (Droop, 1955; Guillard and Ryther, 1962). Recently, Koch et al. (2011) demonstrated that vitamin B12 concentrations strongly influence algal communities in the coastal Gulf of Alaska, with high concentrations favoring dinoflagellates over diatoms, affirming that B-vitamins can indeed play an important ecological role in plankton succession. Despite this renewed interest in B-vitamins, very little is known regarding how the trophic state of coastal ecosystems influences the cycling of vitamins and only one study has investigated B-vitamin concentrations and uptake rates by plankton communities in an aquatic ecosystem (Koch et al., 2011).

The goal of this study was to elucidate the relationships between phytoplankton community composition, carbon fixation, and B-vitamin (B1 and B12) assimilation by coastal plankton assemblages. This field study was performed over 2 years in two contrasting, coastal, marine systems: a hypereutrophic and a mesotrophic estuary. In support of the primary objectives of this study, nutrient, and vitamin amendment experiments were performed to explore the extent to which the availability of vitamins affected phytoplankton biomass and community assemblages.

Materials and Methods

Study sites

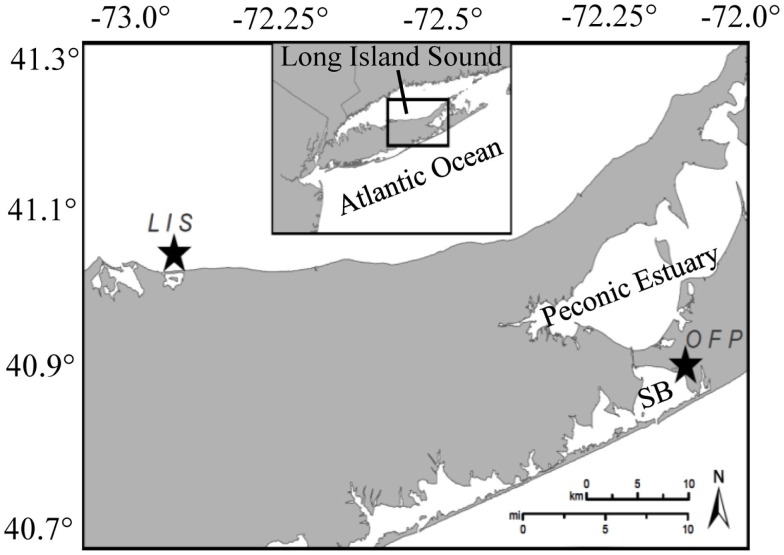

Two estuaries were investigated during this study and were sampled on 18 occasions on a bi-weekly to monthly basis from March 2007 until November 2008 to capture a complete annual cycle of plankton and vitamin dynamics. Water was collected from the mesotrophic portion of Long Island Sound (LIS) near Mount Sinai Harbor (40.97°N, 73.04°W; Figure 1) and a hypereutrophic, tidal tributary on eastern Shinnecock Bay, Old Fort Pond (OFP, 40.87°N, 72.45°W, Figure 1). LIS is a large, urban estuary bordered on the western end by New York City and in the east exchanges with the North Atlantic Ocean, thus displaying a strong east-west eutrophication gradient (Gobler et al., 2006). Our sampling location was located within the eastern, mesotrophic half of this estuary. OFP exchanges tidally with Shinnecock Bay and is a shallow (<2 m), well-mixed, hypereutrophic body of water which, during the summer months, experiences dense algal blooms that create a large demand for micro- and macro-nutrients and may be influenced by the availability of vitamins (Gobler et al., 2007). This inland, hypereutrophic tributary with high levels of mixed algal biomass (up to 50 μg Chl a L−1; Gobler et al., 2007) contrasts with the LIS location which typically displays lower levels of algal biomass (mesotrophic; ∼3 μg Chl a L−1; Gibson et al., 2000).

Figure 1.

A map of Long Island, NY showing the two study sites (stars). OFP denotes Old Fort Pond, a hypereutrophic systems which exchanges tidally with the Atlantic Ocean through Shinnecock Bay (SB). The second study site, Long Island Sound (LIS), was sampled at the incoming tide from a dock at the Mount Sinai Harbor entrance and represents a mesoeutrophic system.

Chemical analysis

Water for nutrient analysis was filtered through pre-combusted GF/F filters. Concentrations of nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, and phosphate were determined in duplicate by standard spectrophotometric methods (Jones, 1984; Parsons et al., 1984). Total dissolved nitrogen and phosphorus (TDN, TDP) were analyzed in duplicate by persulfate oxidation techniques (Valderrama, 1981) and dissolved organic nitrogen and phosphorus (DON and DOP) calculated by subtracting levels of nitrate, nitrite and ammonium, or orthophosphate from concentrations of TDN and TDP, respectively. Full recoveries (mean ± 1 SD) of samples spiked with SPEX Certi-PrepINC standard reference material for TDN, TDP, nitrate, nitrite and ammonium, and orthophosphate were obtained at environmentally representative concentrations. Vitamin samples were collected and analyzed according to Okbamichael and Sanudo-Wilhelmy (2004, 2005). Briefly, water was filtered through 0.2 μm capsule filters (GE Osmonics, DCP0200006) into 1 L LDPE bottles and stored frozen and in the dark. The samples were then acidified and concentrated at 1 mL min−1 onto columns containing 17% High Capacity C18 (Varian, HF BONDESIL), stored frozen, and analyzed via reverse phase HPLC.

Characterization of the plankton community

Several approaches were utilized to characterize resident plankton communities. Size fractionated chlorophyll a (Chl a) samples were collected by filtering triplicate samples onto 0.2 and 2 μm polycarbonate filters. These filters were stored frozen until analysis via standard fluorometric methods (Welschmeyer, 1994). Whole seawater was also preserved in 5% Lugols iodine solution for enumeration of plankton (>5 μm) under an inverted microscope. Organisms were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible and were generally grouped as diatoms, dinoflagellates, ciliates, and autotrophic nanoplankton. A minimum of 200 organisms or 100 grids were be counted per sample (Omori and Ikeda, 1984). Whole water samples were preserved with 10% buffered formalin (0.5% v/v final) and analyzed flow cytometrically to assess picoplankton densities (Olson et al., 1991). Abundance of heterotrophic bacteria (stained with SYBR Green I; Jochem, 2001), phycoerythrin-containing picocyanobacteria, and photosynthetic picoeukaryotes were quantified using a FACScan (BD®) flow cytometer using fluorescence patterns and particle size from side angle light scatter (Olson et al., 1991).

Primary production and vitamin uptake

A 57Co-labeled vitamin B12 from MP-Biomedicals (specific activity 7.84 MBq μg−1; half-life 272 days) and a 3H-labeled B1 (specific activity 0.37 MBq mmol−1; half-life 12.3 years) were used to measure planktonic uptake rates of these vitamins largely following the methods described by Koch et al. (2011). While vitamin B12 assimilation was measured throughout this study, vitamin B1 assimilation was measured for the second half of this study only (3/7/08 to 11/4/08). Since preliminary studies with these tracers revealed linear uptake rates by multiple types of coastal marine plankton assemblages over 24 h without displaying a diel pattern, incubations were carried out for 1 day. Measured uptake rates never depleted more than 15 ± 6.3 and 7.7 ± 2.2% of vitamin B1 and B12 standing stocks during these 24 h incubations. Trace amounts (0.5 pM B12, 1.48 kBq) of 57Co-cyanocobalamin and 3H-thiamine (2 pM, 2.22 kBq) were added to separate sets of triplicate, 300 mL polycarbonate bottles. To assess abiotic binding of radiolabeled vitamin B1 and B12 to particles and, thus, establish a “blank,” several approaches were explored including incubations of natural plankton communities from LIS for 24 h in the dark at 1°C, and with the addition of mercuric chloride and glutaraldehyde at final concentrations of 1%. All of these approaches exhibited similarly low levels of abiotic binding and 1% glutaraldehyde was ultimately chosen as a “killed control” method with one such bottle being spiked with tracer and incubated along the “live” bottles during all experiments. The background activity for detection of 57Co was generally between 20 and 40 counts per minute while samples ranged from 80 to 1500 counts per minute.

To determine primary productivity rates, 0.37 MBq of 14C-bicarbonate (MP-Biomedicals©, specific activity 2035 MBq mmol−1) was added to triplicate bottles according to Joint Global Ocean Flux Study (JGOFS) protocols (1994). All bottles were incubated in an incubator set to mimic ambient light and temperature conditions. Incubations were terminated after 24 h by filtering up to 100 mL from both live and dead bottles onto 0.2 and 2 μm pore size polycarbonate filters, allowing for the determination of size fractionated uptake of the tracers. At the beginning and end of the incubation, a small aliquot of each bottle (250 μL for 14C and 1 mL for 3H and 57Co) was removed to quantify total activity. The 57Co containing experimental filters and total activities were analyzed on a LKB Wallac 1282 Compugamma gamma counter equipped with a NaI(Tl) well detector, while the 14C and 3H samples were measured with a scintillation counter (PackardCarb2100TR). Uptake rates of vitamins B1 and B12 were calculated by using the equation: [(Af − AD/Atot) × (vitamin)]/t where Af is the activity on the live filters, AD is the activity on the dead (“killed control”) filters, Atot is the total activity added, (vitamin) is the ambient B1 or B12 concentration and t equals the length of the incubation in days. Similarly, uptake of 14C-bicarbonate was determined according to the JGOFS (1994) protocol.

Using cell counts obtained via flow cytometry, size fractionated Chl a concentrations, estimated carbon contents of heterotrophic bacteria and cyanobacteria and previously published C: Chl a ratios, carbon-specific vitamin uptake rates were calculated for both size classes and systems. For the >2 μm plankton, a carbon: Chl a ratio of 60 obtained from estuaries including LIS was used (Lorenzen, 1968; Riemann et al., 1989; Boissonneault-Cellineri et al., 2001) while previously published values of average carbon contents of 20 Fg cell−1 for heterotrophic bacteria (Fukuda et al., 1998; Ducklow, 2000), and 200 and 250 Fg cell−1 for cyanobacteria and picoeukaryotes (Kana and Glibert, 1987; Liu et al., 1999; Worden et al., 2004), respectively were used for the <2 μm size class.

Vitamin amendment experiments

On each sampling date, water from both sites was used to conduct nutrient/vitamin amendment experiments. Acid-washed, polycarbonate bottles (1.1 L) were filled and amended in triplicate with either 20 μM nitrate, 100 pM B12, or both nutrients while another triplicate set was left unamended as a control treatment. The bottles were then incubated for 48 h in OFP mimicking ambient light and temperature conditions (Gobler et al., 2007). To assess phytoplankton responses, bottles were analyzed for size fractionated Chl a (0.2 and 2 μm polycarbonate filters) and net growth rates were estimated for the different size fractions based on changes in pigment concentrations using the formula: (μ = lnBfinal/Binitial)/incubation time where Bfinal is the Chl a in bottles at the end of experiments, Binitial is the Chl a in bottles at the beginning of the experiments, and the incubation time is days.

Data analysis

Relationships between environmental parameters were evaluated by means of a Spearman rank order correlation matrix. p-values <0.05 were deemed to be significantly correlated and the correlation coefficient is reported as R. For nutrient amendment experiments, differences in growth rates among treatments for each size class of plankton pigments were statistically evaluated using two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) with N and B12 as the main effects. p < 0.05 was used to establish significant differences among treatments. To assess seasonal trends, the data was also grouped seasonally into spring (March 21–June 20), summer (June 21–September 20), fall (September 21–December 20), and winter (December 21–March 20).

Results

Nutrient and vitamin dynamics

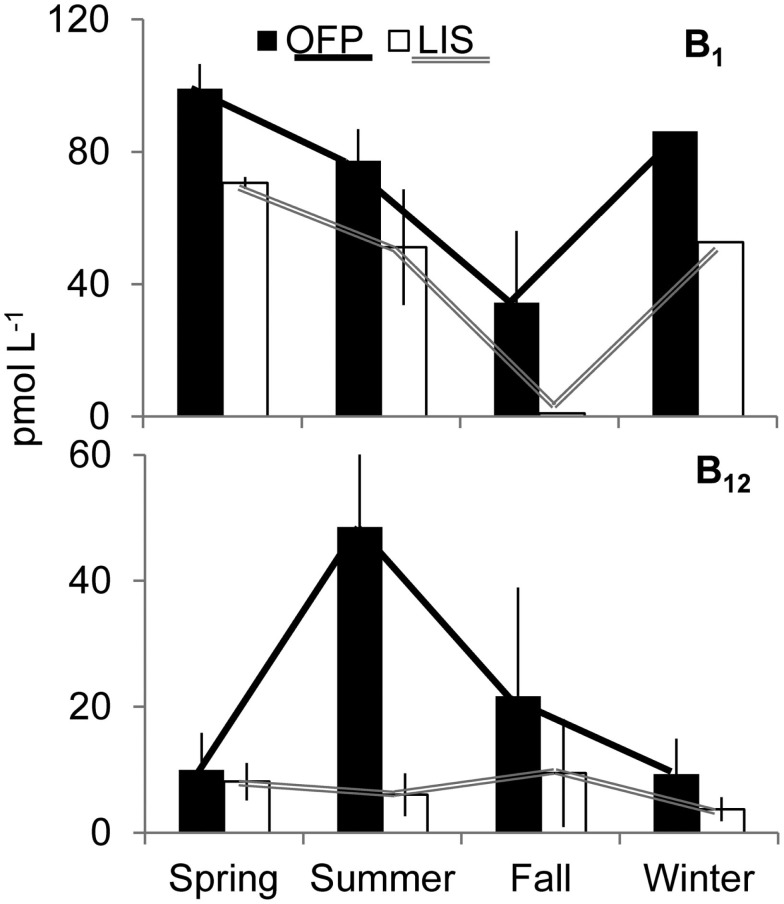

Dissolved inorganic nutrients and vitamin concentrations in OFP were seasonally dynamic (Figure 2; Table 1). DIN (nitrate + nitrite + ammonium) concentrations varied inversely with water temperature being significantly (p < 0.001) higher in the Winter and Spring than in Summer and Fall. In contrast, vitamin B12 concentrations (range: <0.1–148 pmol L−1; Table 1) were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the Summer and Fall (48.6 ± 32.7 and 21.7 ± 17.3 pmol L−1; seasonal average ± SE) than the Spring and Winter (9.95 ± 5.89 and 9.29 ± 4.36 pmol L−1, respectively). Concentrations of B1 were, on average, higher than vitamin B12 (34.9 ± 21.7–99.1 ± 7.46; Table 1) and displayed no clear seasonality (Figure 2). Vitamin B12 concentrations were significantly higher in 2008 (55.2 ± 30.7 pmol L−1) than 2007 (7.07 ± 1.61 pmol L−1; Table 1). In LIS, levels of DIN, DIP, and vitamins were all significantly lower than OFP (Table 1, p < 0.05 for all) and generally highest in Winter and Spring. Vitamin B12 concentrations in LIS ranged from <0.1–43 pmol L−1 and B1 concentrations ranged from <0.1 to 99 pmol L−1 (Table 1). Unlike OFP, seasonal averages of B12 in LIS were higher in Spring and Fall, while levels of B1 were highest in the Spring and low (<0.1 pmol L−1) in the Fall (Figure 2; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Seasonally averaged concentrations of B1 (top) and B12 (bottom) in Old Fort Pond and Long Island Sound, NY. The solid and hollow lines accentuate the seasonal trend of vitamins in Old Fort Pond and Long Island Sound, respectively. Concentrations are shown in pmol L−1.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical characteristics of old fort pond and long island sound over the course of the study.

| Temperature °C |

Salinity | DIN μmol L−1 |

μmol L−1 |

Si(OH)4 μmol L−1 |

B12 pmol L−1 |

B1 pmol L−1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFP | |||||||

| 3/26/2007 | 7.9 | 29.6 | 11.2 ± 1.9 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 8.4 ± 1.5 | 0.3 | ND |

| 4/16/2007 | 9.1 | 24.4 | 18.9 ± 1.4 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 12.1 ± 0.0 | 6.8 | ND |

| 4/30/2007 | 12.5 | 24.6 | 21.3 ± 1.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 17.2 ± 2.1 | 7.9 | ND |

| 5/21/2007 | 14.8 | 28.7 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 12.9 ± 0.2 | 2.7 | ND |

| 6/19/2007 | 21.1 | 20.5 | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 43.7 ± 0.1 | 9.0 | ND |

| 7/10/2007 | 24.6 | 24.3 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 54.8 ± 0.4 | 3.7 | ND |

| 8/8/2007 | 25.5 | 26.9 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 41.8 ± 0.4 | 15.5 | ND |

| 8/29/2007 | ND | ND | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 39.1 ± 3.3 | 17.0 | ND |

| 9/26/2007 | 21.8 | 28.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 21.2 ± 6.4 | 13.0 | ND |

| 11/5/2007 | 11.2 | 28.5 | 7.1 ± 2.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 4.3 | ND |

| 12/4/2007 | 3.9 | 27.0 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 | ND |

| 1/8/2008 | 3.4 | 25.4 | 36.2 ± 6.2 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 46.3 ± 4.6 | 3.7 | ND |

| 3/17/2008 | 5.6 | 28.2 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 14.9 | 86.3 |

| 4/14/2008 | 10.4 | 27.5 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 3.1 | 112.0 |

| 5/19/2008 | 16.2 | 26.5 | 29.3 ± 2.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 10.9 ± 2.8 | 38.9 | 86.1 |

| 6/25/2008 | 23.1 | 27.8 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 30.7 ± 4.9 | 158.0 | 79.0 |

| 7/30/2008 | 27.0 | 25.6 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 25.1 | 52.1 |

| 9/4/2008 | ND | ND | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.2 | ND | 114.6 |

| 9/30/2008 | 20.2 | 27.2 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 21.9 ± 1.1 | 90.1 | 68.7 |

| 11/4/2008 | 10.7 | 28.4 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 18.9 ± 0.3 | <0.10 | 0.1 |

| LIS | |||||||

| 3/26/2007 | 3.9 | 26.0 | 13.7 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 5.7 | ND |

| 4/16/2007 | 6.2 | 25.9 | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 0.3 | ND |

| 4/30/2007 | 9.8 | 24.0 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 8.9 ± 3.2 | 6.0 | ND |

| 5/21/2007 | 11.6 | 25.0 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 13.2 ± 0.6 | 10.7 | ND |

| 6/19/2007 | 18.2 | 25.3 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 18.0 ± 2.0 | 2.8 | ND |

| 7/10/2007 | 20.5 | 26.8 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 4.0 | ND |

| 8/8/2007 | 23.1 | 27.1 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 35.9 ± 0.4 | 4.3 | ND |

| 8/29/2007 | ND | ND | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 66.9 ± 3.0 | 1.9 | ND |

| 9/26/2007 | 21.8 | 28.1 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 26.3 ± 0.6 | 0.3 | ND |

| 11/5/2007 | 15.1 | 28.3 | 12.1 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 43.3 ± 1.9 | 2.5 | ND |

| 12/4/2007 | 7.6 | 28.2 | 14.1 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 42.4 ± 5.3 | 0.9 | ND |

| 1/8/2008 | 4.8 | 28.2 | 14.5 ± 3.5 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 50.7 ± 0.9 | 1.8 | ND |

| 3/17/2008 | 3.7 | 26.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 5.6 | 52.7 |

| 4/14/2008 | 6.9 | 25.7 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 21.3 | 73.7 |

| 5/19/2008 | 12.1 | 24.7 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.7 | 67.5 |

| 6/25/2008 | 20.0 | 25.9 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 | <0.10 |

| 7/30/2008 | 22.1 | 26.8 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 34.5 ± 0.3 | 27.5 | 54.8 |

| 8/12/2008 | 21.8 | 26.7 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 35.9 ± 1.2 | 1.0 | 98.8 |

| 9/30/2008 | 19.7 | 25.7 | 15.8 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 0.0 | 33.5 ± 12.5 | <0.10 | <0.10 |

| 11/4/2008 | 11.9 | 26.7 | 9.7 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 38.9 ± 0.5 | 43.7 | <0.10 |

Note that B1 concentrations were not measured until the second part of the study (3/17/08–11/4/08).

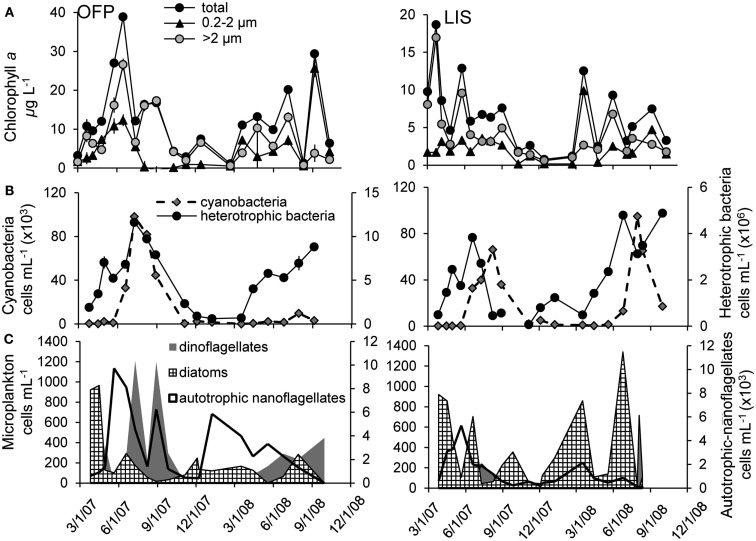

Plankton community succession

Chl a concentrations in OFP varied from 1.12 ± 0.04 to 38.9 ± 0.89 μg L−1 (mean = 12.7 ± 2.78; Figure 3A). Size fractionation of Chl a revealed a seasonal succession with larger photoautotrophs being most dominant in the Spring, Summer, and Fall and all size classes contributing equally to the algal biomass during Winter (Figure 3A). Heterotrophic bacteria abundances were high, ranging from 0.6 to 11.6 × 106 cells mL−1 while densities of picocyanobacteria were lower, 0.11–98.2 × 103 cells mL−1 (Figure 3B). Both populations displayed maximal densities during Summer and Fall months with densities of both populations being significantly correlated to water temperature (p < 0.01; Figure 3B). The microphytoplankton community in OFP was dominated by autotrophic nanoflagellates and dinoflagellates in the Summer and Fall with diatoms present during the Winter and early Spring only (Figure 3C). In contrast to OFP, the annual mean of plankton biomass in LIS was significantly lower throughout the year (6.55 ± 1.33 vs. 12.7 ± 2.78 μg Chl a L−1 for OFP), ranging from <1 μg L−1 in winter to 18.7 ± 1.79 μg L−1 during the spring bloom in 2007 and, with a few exceptions, was dominated by large (>5 μm) diatoms (Figures 3A,C). Heterotrophic bacteria and cyanobacterial abundances in LIS were substantially lower than in OFP with abundances correlating strongly with phytoplankton biomass (Chl a, p < 0.001) and temperature (p = 0.001; Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Planktonic community composition from 2007 to 2008 in Old Fort Pond (left) and Long Island Sound (right), NY. Size fractionated chlorophyll a (A) was obtained using varying pore size polycarbonate filters, cyano-, and heterotrophic bacteria concentrations were measured via flow cytometry (B) and the nano- and microplankton community was determined via light microscopy (C).

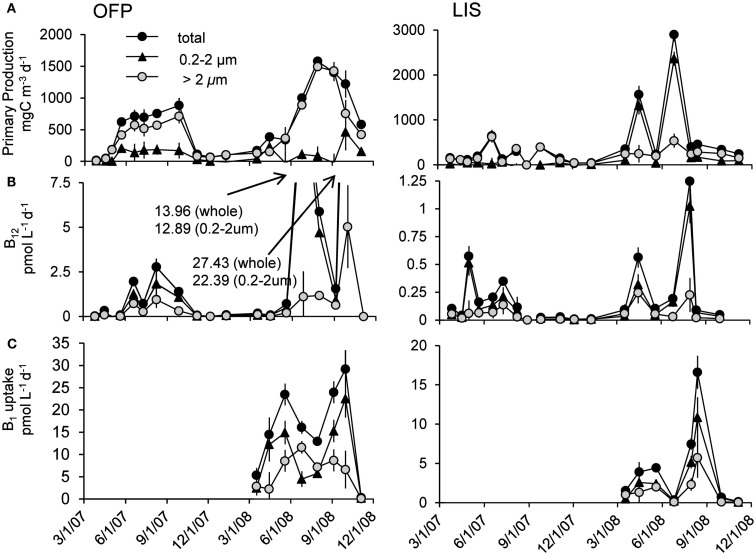

Primary production and vitamin uptake

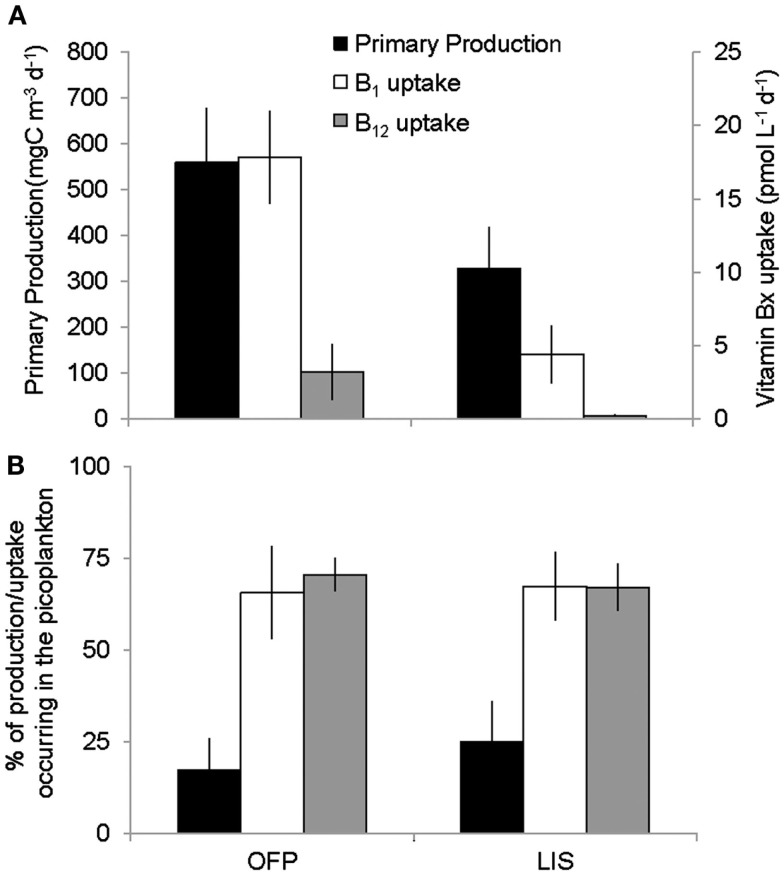

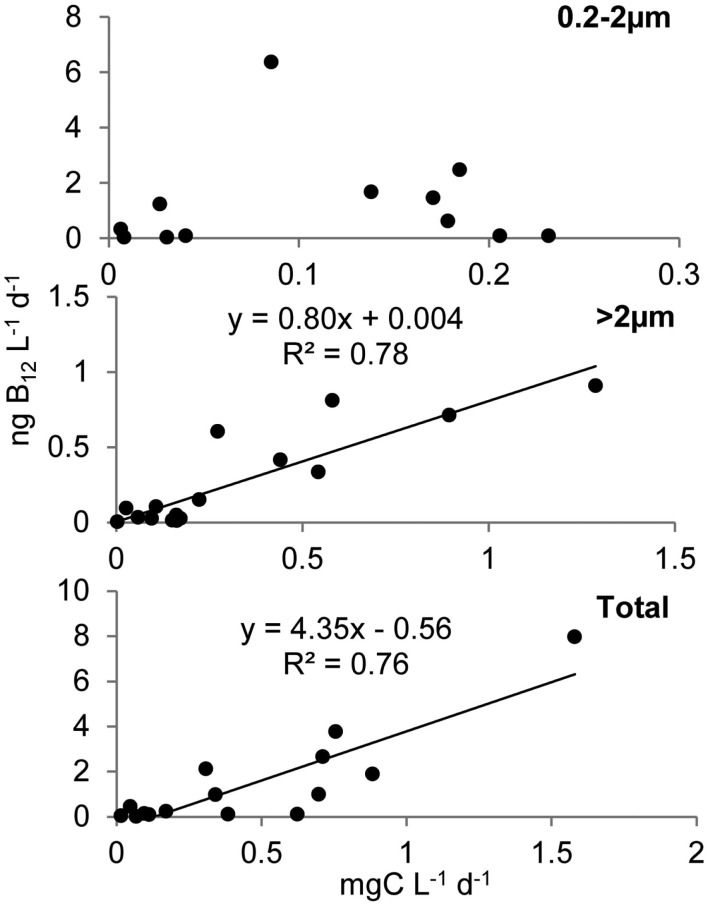

Primary production rates in OFP displayed a strongly seasonal signal with extremely high rates (607 ± 118 mg C m−3 day−1) in the Summer of both years (Figures 4A and 5). With few exceptions, the majority of this productivity occurred in the >2 μm size fraction (Figure 4A). Vitamin B12 uptake followed a similar seasonal trend with uptake rates ranging from <0.1 to 27.4 ± 2.32 pmol L−1 day−1 and the highest rates observed in Summer and Fall (mean = 3.07 ± 0.57; Figures 4B and 5). In contrast, B1 uptake rates, which were higher, displayed little seasonality, ranging from 0.32 ± 0.01 to 29.5 ± 2.45 pmol L−1 day−1 (mean = 14.4 ± 0.79; Figures 4C and 5). In stark contrast to primary production, picoplankton (0.2–2 μm) were responsible for the majority of vitamin B1 and B12 uptake in OFP (>65% from Spring-Fall; Figures 4 and 5). While there was no relationship between vitamin uptake and primary production among plankton <2 μm, among larger plankton (>2 μm) these rates were significantly correlated (r = 0.88; Figure 6). Notably, the scale of vitamin uptake for the picoplankton was about 10-fold higher than in the >2 μm size fraction.

Figure 4.

Time series of primary productivity (A), vitamin B12 (B), and B1 (C) uptake dynamics in Old Fort Pond (left) and Long Island Sound (right), NY. Size fractionated primary production and uptake measurements were obtained via the use of polycarbonate filters and are reported in mg C m−3 day−1 and pmol L−1 day−1, respectively.

Figure 5.

Seasonal averages of primary production and vitamin B12 and B1 uptake (A) and the percent of uptake occurring in the picoplankton (0.2–2 μm) size fraction (B) in the two systems studied. OFP stands for Old Fort Pond while LIS denotes Long Island Sound. Values shown are seasonal means ± SE.

Figure 6.

Relationship between B12 and carbon uptake in Old Fort Pond. Uptake of B12 and bicarbonate are reported as ng L−1 day−1 and mg L−1 day−1 respectively. Regressions show that in the larger size class (>2 μm), uptake of B12 was driven by the photosynthetic organisms in contrast to the <2 μm size class where B12 uptake was not correlated to primary production, with heterotrophic bacteria most likely responsible for the majority of vitamin assimilation.

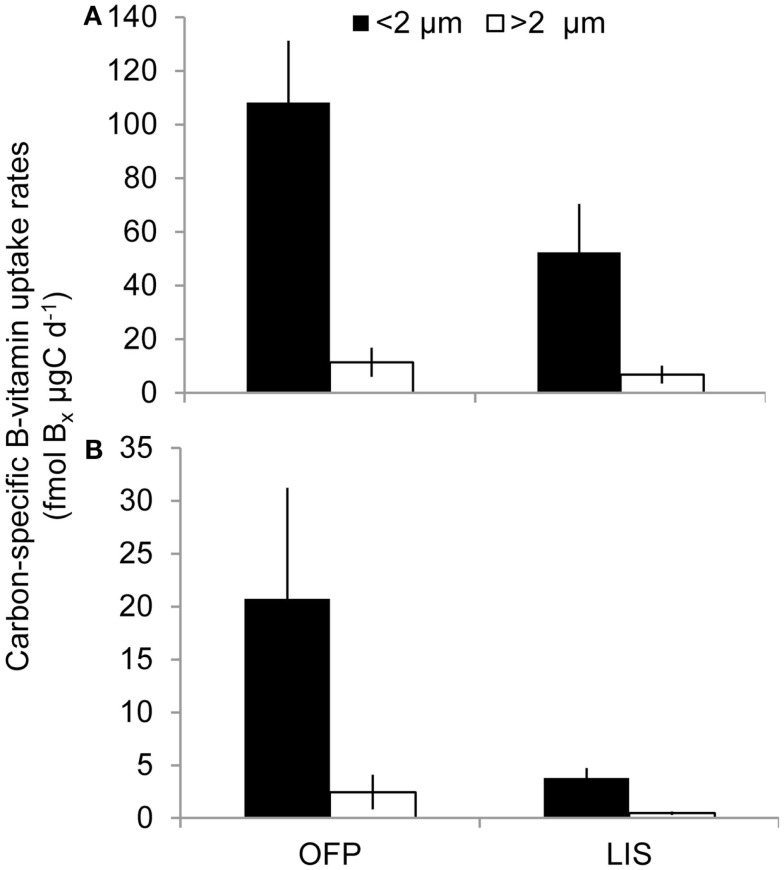

Mean primary production rates in LIS (343.4 ± 96.8 mg C m−3 day−1) were twofold lower than OFP, and peak rates were confined to Spring and Fall of both years (Figures 4A and 5). Like in OFP, larger phytoplankton (>2 μm) accounted for the majority of primary production in LIS (Figure 4). Vitamin B12 (0.22 ± 0.08 pmol L−1 day−1) and B1 (4.39 ± 1.96 pmol L−1 day−1) uptake rates were 10- and 4-fold lower in LIS than OFP, respectively (Figures 4B,C). Like OFP, picoplankton were responsible for the majority of vitamin assimilation in LIS (>55% for all seasons, Figures 4 and 5). Carbon-specific vitamin uptake rates calculated for both size classes and systems revealed striking differences between picoplankton and the >2 μm size class. Specifically, picoplankton utilized an order of magnitude more B1 and B12 per gram of carbon (Figure 7). In addition, there were 200 and 550% higher vitamin uptake for B1 and B12 normalized to carbon, respectively in OFP compared to LIS.

Figure 7.

Average B1 (A) and B12 (B) uptake rates normalized to particulate organic carbon (see Materials and Methods) for each size class and location over the course of the study. Values are shown as fmol of Bx μg C−1 day−1, where Bx stands for the corresponding B-vitamin.

Vitamin amendment experiments

Experiments conducted using water from OFP and LIS revealed that nitrogen frequently stimulated phytoplankton biomass (56% of experiments, Table 2) and generally did so for both large and small phytoplankton (> and <2 μm). While B12 additions only occasionally enhanced larger algal biomass (>2 μm; 11% of experiments) it more frequently enhanced the growth rate of the 0.2- to 2-μm size fraction (28% of experiments; Table 2). When added together, nitrogen and B12 enhanced total algal biomass more than each individual treatment in 20% of experiments, suggesting a co-limitation of the community by both compounds. The >2 μm size class was more frequently enhanced in this treatment and most of these effects were observed in the Summer and Fall.

Table 2.

Responses to nitrogen and vitamin B12 amendments by different size classes of phytoplankton collected from OFP and LIS.

| Total | 0.2–2 μm | >2 μm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFP (n = 18) | B12 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| N | 9 | 5 | 8 | |

| N + B12 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| LIS (n = 18) | B12 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| N | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| N + B12 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| ALL (n = 36) | B12 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| N | 20 | 16 | 18 | |

| N + B12 | 6 | 6 | 9 | |

Responses for each size fraction were measured via changes in chlorophyll a over time and are shown for each sample location. In addition overall effects were examined by looking at all the experiments conducted for each size class (ALL). An effect of the NO3 + B12 treatments was deemed significant when p < 0.05 compared to the NO3 and B12 only additions. Values represent the number of times a treatment resulted in a positive growth response in that size class.

Discussion

Although the potential for B-vitamins to influence the structure and productivity of phytoplankton communities has been recognized for decades, this study is the first to investigate vitamin B1 and B12 uptake by plankton communities in an aquatic ecosystem. Performing this investigation in two contrasting estuaries (mesotrophic vs. hypereutrophic), this study specifically documented high vitamin concentrations and uptake rates in eutrophic regions that host elevated primary production and heterotrophic bacterial abundances. Although phytoplankton communities were occasionally stimulated by the addition of vitamin B12 alone and in tandem with nitrogen, it was the picoplankton community that was responsible for most of the vitamin uptake during this study. The sum of the data collected suggests that within this size class, heterotrophic bacteria were responsible for the majority of the vitamin uptake in both systems and in all seasons.

Vitamin availability

The two systems studied here displayed vastly different chemical and biological characteristics, with the OFP containing higher nutrient (Table 1), Chl a, and vitamin concentrations than LIS (Figures 2–4). While seasonally averaged primary production values did not vary significantly between the sites (Figure 5), OFP had much larger sustained primary productivity rates throughout the Summer and Fall as evidenced by the reduced variability among seasonal averages. Only prokaryotes possess the genes necessary to synthesize vitamin B12 (Warren et al., 2002; Rocap et al., 2003; Newton et al., 2010) and the twofold higher heterotrophic bacterial densities in OFP likely resulted in higher rates of de novo vitamin synthesis and concentrations. Gobler et al. (2007) found a strong linear relationship between bacterial abundance and B12 concentrations in OFP in summer, a time when the highest vitamin concentrations and uptake rates were observed. Cyanobacteria populations can also produce vitamins (Parker, 1977; Palenik et al., 2003; Bonnet et al., 2010) and were also present at higher concentrations in OFP (Figure 3) compared to LIS. Abundances of both groups of picoplankton were strongly correlated with water temperature (p < 0.01) a fact which likely contributed to the seasonal peaks in B12 observed in OFP during Summer and Fall (Figure 2) but not in LIS where B12 concentrations and primary production were less dynamic (Figure 2). For both systems, primary productivity and B12 concentrations were strongly correlated (r = 0.61; p < 0.005) suggesting a tight coupling between photoautotrophs and B12 producing prokaryotes. In contrast, vitamin B1 was inversely correlated with bacterial biomass (r = −0.63, p < 0.05) and primary production (r = −0.74, p < 0.05). Given that vitamin B1 requirements of phytoplankton generally exceed those of vitamin B12 (Tang et al., 2010) and that vitamin B1 uptake rates exceeded those of vitamin B12, these inverse correlations may reflect a larger net microbial (phytoplankton and bacteria) uptake of this vitamin.

Vitamin uptake

B-vitamins were actively utilized by phytoplankton as total uptake rates of B12 and total primary production in both systems were highly correlated (r = 0.80, p < 0.001). Examining this trend among the different size fractions indicated that while primary production and vitamin uptake in the >2 μm size were also positively correlated (r = 0.83, p < 0.001), this was not true for the picoplankton (<2 μm) despite 10-fold higher vitamin uptake rates in this size class (Figure 6). The strong correlation between vitamin uptake and primary production in the >2 μm size class is consistent with the fact that most phytoplankton are B12 auxotrophs (Croft et al., 2005). The absence of such a relationship among picoplankton suggests auxotrophic, heterotrophic bacteria were responsible for the majority of the vitamin use. Peak vitamin uptake rates in OFP exceeded those of LIS by an order of magnitude (Figure 5) and OFP microphytoplankton were dominated by dinoflagellates through much of this study, a group with a high incidence of vitamin B12 and B1 auxotrophy (91 and 41%, respectively; (Tang et al., 2010). In LIS, phytoplankton communities were generally dominated by diatoms, another group with widespread vitamin B12 auxotrophy (Provasoli and Carlucci, 1974; Croft et al., 2005) and diatom abundances in LIS were also positively correlated with vitamin B12 uptake by the >2 μm size class (r = 0.65, p < 0.02).

This study reports the first vitamin B1 uptake rates by aquatic plankton communities and reveals important similarities and differences between these rates and those of vitamin B12 uptake. Similar to the ambient B1 concentrations (Figure 2), uptake rates of that vitamin were an order of magnitude higher than B12 uptake rates (Figure 5). Like vitamin B12, B1 assimilation also occurred primarily in the picoplankton size class (60.0 ± 5.60 and 62.8 ± 5.10% for OFP and LIS respectively; Figure 5) suggesting that bacteria may hold a competitive advantage over larger phytoplankton for access of this micronutrient. Vitamin B1 uptake rates in LIS and OFP were generally higher in the Spring, Summer, and Fall, paralleling patterns for vitamin B1 concentration (Figure 2), likely due to temperature dependency of microbial metabolisms. Unlike vitamin B12, B1 uptake rates were not correlated with any plankton group suggesting that multiple plankton groups were important for B1 uptake or that groups not definitively documented by this study were important vitamin B1 users.

A lack of correlation between primary production and vitamin uptake in the picoplankton (Figure 6), 10- to 100-fold greater heterotrophic bacteria biomass (104 ± 16.0 and 42.2 ± 7.35 μg C L−1 for OFP and LIS, respectively) compared to phototrophic picoplankton (3.34 ± 1.48 and 4.44 ± 1.42 μg C L−1 for OFP and LIS, respectively), and a strong correlation between heterotrophic bacterial abundances and B12 uptake (p < 0.008), all suggest that heterotrophic bacteria were the group responsible for the majority of vitamin uptake during this study. Several recently sequenced marine bacterial genomes possess B12 dependent enzymes while lacking genes for B12 synthesis (Medigue et al., 2005), suggesting that in addition to being B12 synthesizers (Warren et al., 2002; Rocap et al., 2003; Newton et al., 2010) marine heterotrophic bacteria might also be important vitamin consumers. Cyanobacteria and picoeukaryote populations in OFP for 2008 were low (<104 cells mL−1) when vitamin uptake rates were the highest recorded for the study (Figures 3 and 4), again implicating heterotrophic bacterial community as the most important group for vitamin assimilation. This study highlights the importance of picoplankton in vitamin consumption and suggests that vitamins are primarily assimilated by heterotrophic bacteria, even when larger (>2 μm), eukaryotic cells dominate plankton biomass (>85% of the total POC during spring and summer). As such, previously reported paradoxically low vitamin concentrations in areas of high bacterial activity such as the deeper LIS waters during summer hypoxia (Panzeca et al., 2009) may be due to a large vitamin demand by actively growing heterotrophic bacteria outpacing the vitamin supply or low vitamin production.

Vitamins alter plankton community composition

In both OFP and LIS, vitamin B12 amendments stimulated total Chl a production in 12% of experiments (Table 2) while eliciting size structure changes in nearly half of experiments (47%). In OFP, B12 limited phytoplankton solely in the Winter and Spring times when vitamin concentrations were lowest (Table 1). In contrast to OFP, phytoplankton in LIS were most limited by vitamins in the summer and fall. The significant correlation between primary production and B12 concentrations (r = 0.83, p < 0.005) as well as between heterotrophic bacterial densities and B12 concentrations (r = 0.47, p = 0.05) suggest that increases in heterotrophic bacteria, fueled by the high primary production, likely led to increased vitamin production and the alleviation of vitamin limitation. As such, the supply of vitamins by bacteria likely influenced vitamin limitation of the phytoplankton in both systems. This conclusion is consistent with Bertrand et al. (2007, 2011) who found vitamins limited phytoplankton communities in coastal regions of the Ross Sea only when bacterial densities were low. As has been previously observed (Gobler et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2011), the addition of B12 in conjunction with nitrogen led to increased growth rates over B12 or nitrogen alone, a result that may be partly elicited by an increase in B12 demand due in the presence of extra nitrogen. This occurred most frequently in the >2 μm size fraction. While uptake rates of vitamin B12 were tightly coupled to primary production in this larger size class (Figure 6), the rate of vitamin uptake for that size class was <35% of the total vitamin consumption suggesting that the uptake of the low concentrations of vitamins is dominated by the picoplankton (Figure 4), but that both groups are occasionally limited by the availability of vitamin B12.

A revised notion of B-vitamin cycling

Karl (2002) hypothesized that in marine ecosystems, vitamins are produced by bacteria and utilized by larger phytoplankton and while the importance of B-vitamins in phytoplankton physiology has been well-established, the ecological relevance of these micronutrients in the field has been questioned (Droop, 1961, 1968, 1970, 2007). Although prior culture studies suggested that vitamins are present at high enough concentrations to satisfy algal demand, these studies relied on bioassays to estimate the levels of vitamins in the world’s oceans. Furthermore phytoplankton are often stimulated experimentally by the addition of B-vitamins (Panzeca et al., 2006; Sanudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2006; Bertrand et al., 2007; Gobler et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2011). This paradigm may be best explained by the revelation that, in addition to being the source of B-vitamins (Medigue et al., 2005; Bonnet et al., 2010; Bertrand et al., 2011), prokaryotes are also the main sink for these micronutrients in marine systems (Figures 4 and 5; Koch et al., 2011) and vitamin uptake by these microbes may, on occasion, deprive eukaryotic phytoplankton of a sufficient vitamin supply. The higher vitamin demand by the plankton communities in OFP point to a microbial community adapted to higher vitamin concentrations in this more eutrophic systems with higher ambient vitamin concentrations. The higher carbon normalized B12-vitamin demand in OFP may be caused by the denser heterotrophic bacterial populations with a higher percentage of vitamin auxotrophs. Similarly, the dominance of dinoflagellates (Figure 3), a group comprised almost exclusively of auxotrophs (Tang et al., 2010), in OFP likely accounted for the large >2 μm B12 demand per unit carbon there (Figure 7). This group was rare in LIS.

Recent work exploring natural ecosystems (Bertrand et al., 2011), cyanobacterial cultures (Bonnet et al., 2010), and prokaryotic genomes (Raux et al., 2000; Palenik et al., 2003; Newton et al., 2010) have highlighted the important role of prokaryotes in ocean vitamin production and consumption. While it is unknown whether specific groups of vitamin producers are also responsible for vitamin assimilation, this would seem counterintuitive since vitamin biosynthesis is complicated and, in the case of B12 utilities numerous genes and enzymatic steps (Raux et al., 2000; Warren et al., 2002). Due to the demanding nature of this process, B-vitamin auxotrophic bacteria may harbor an energetic advantage over vitamin-producing bacteria and seem to hold a kinetic advantage in assimilating picomolar levels of vitamins over larger, vitamin auxotrophic phytoplankton likely due to their larger surface to volume ratio (Raven and Kubler, 2002). In addition, the faster doubling times and higher biomass of heterotrophic bacteria (Giovannoni et al., 2005) likely leads to a much higher vitamin demand compared to larger, slower growing phytoplankton and the development of vitamin depleted surface oceans observed by Sañudo-Wilhelmy et al. (2012). Regardless, we hypothesize that vitamin cycling (uptake and production) occurs primarily within the prokaryotic picoplankton community, a factor which may limit the growth of some eukaryotic phytoplankton cells.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. James Hofmann and Gordon Taylor for helpful comments on this manuscript. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation’s Biological Oceanography and Chemical Oceanography programs, awards 0623432 and 0962209 to Christopher J. Gobler and Sergio Sanudo-Wilhelmy, respectively. In addition we thank Y.Z. Tang for the many insightful discussions. This work would not have been possible without the help of S. Zegers as well as numerous undergraduates from SoMAS as well as graduate students from the Gobler Laboratory. We thank the Stony Brook/Southampton Marine Station Staff for logistical assistance.

References

- Anderson D. M., Burkholder J. M., Cochlan W. P., Glibert P. M., Gobler C. J., Heil C. A., et al. (2008). Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: examining linkages from selected coastal regions of the United States. Harmful Algae 8, 39–53 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E. M., Saito M. A., Jeon Y. J., Neilan B. A. (2011). Vitamin B-12 biosynthesis gene diversity in the Ross Sea: the identification of a new group of putative polar B-12 biosynthesizers. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1285–1298 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E. M., Saito M. A., Rose J. M., Riesselman C. R., Lohan M. C., Noble A. E., et al. (2007). Vitamin B-12 and iron colimitation of phytoplankton growth in the Ross Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 1079–1093 10.4319/lo.2007.52.3.1079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boissonneault-Cellineri K. R., Mehta M., Lonsdale D. J., Caron D. A. (2001). Microbial food web interactions in two Long Island embayments. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 26, 139–155 10.3354/ame026139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet S., Webb E. A., Panzeca C., Karl D. M., Capone D. G., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2010). Vitamin B-12 excretion by cultures of the marine cyanobacteria Crocosphaera and Synechococcus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1959–1964 10.4319/lo.2010.55.5.1959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder J. M., Glibert P. M., Skelton H. M. (2008). Mixotrophy, a major mode of nutrition for harmful algal species in eutrophic waters. Harmful Algae 8, 77–93 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci A. F., Bowes P. M. (1970). Production of vitamin B12, thiamine and biotin by phytoplankton. J. Phycol. 6, 351–357 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1970.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloern J. E. (2001). Our evolving conceptual model of the coastal eutrophication problem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 210, 223–253 10.3354/meps210223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R., Darge R., Degroot R., Farber S., Grasso M., Hannon B., et al. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253–260 10.1038/387253a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croft M. T., Lawrence A. D., Raux-Deery E., Warren M. J., Smith A. G. (2005). Algae acquire vitamin B-12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438, 90–93 10.1038/nature04056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge V. N., Elliott M., Orive E. (2002). Causes, historical development, effects and future challenges of a common environmental problem: eutrophication. Hydrobiologia 475, 1–19 10.1023/A:1020366418295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droop M. R. (1955). A pelagic marine diatom requiring cobalamin. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 34, 229–231 10.1017/S0025315400008730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droop M. R. (1961). Vitamin B12 and marine ecology: the response of Monochrysis lutheri. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 41, 69–76 10.1017/S002531540000151X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droop M. R. (1968). Vitamin B12 and marine ecology. 4. Kinetics of uptake growth and inhibition in Monochrysis lutheri. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 48, 689. 10.1017/S0025315400019238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droop M. R. (1970). Vitamin B12 and marine ecology. 5. Continuous cultures as an approach to nutritional kinetics. Helgolander Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen 20, 629. 10.1007/BF01609935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droop M. R. (2007). Vitamins, phytoplankton and bacteria: symbiosis or scavenging? J. Plankton Res. 29, 107–113 10.1093/plankt/fbm009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ducklow H. W. (2000). “Bacterial production and biomass in the oceans,” in Microbial Ecology of the Oceans, ed. Kirchman D. L. (New York: John Wiley & Sons; ), 552 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda R., Ogawa H., Nagata T., Koike I. (1998). Direct determination of carbon and nitrogen contents of natural bacterial assemblages in marine environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3352–3358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G. R., Carlson R. E., Simpson J., Smeltzer E., Gerritsen J., Chapra S., et al. (2000). Nutrient Criteria Technical Guidance Manual Lakes and Reservoirs. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; EPA-822-B00-001. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni S. J., Tripp H. J., Givan S., Podar M., Vergin K. L., Baptista D., et al. (2005). Genome streamlining in a cosmopolitan oceanic bacterium. Science 309, 1242–1245 10.1126/science.1114057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobler C. J., Buck N. J., Sieracki M. E., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2006). Nitrogen and silicon limitation of phytoplankton communities across an urban estuary: the East River-Long Island Sound system. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 68, 127–138 10.1016/j.ecss.2006.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobler C. J., Norman C., Panzeca C., Taylor G. T., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2007). Effect of B-vitamins (B-1, B-12) and inorganic nutrients on algal bloom dynamics in a coastal ecosystem. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 49, 181–194 10.3354/ame01132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard R. R. L., Ryther J. H. (1962). Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt and Detonula confervacea Cleve. Can. J. Microbiol. 8, 229–239 10.1139/m62-029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler J., Glibert P. M., Burkholder J. M., Anderson D. M., Cochlan W., Dennison W. C., et al. (2008). Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: a scientific consensus. Harmful Algae 8, 3–13 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holligan P., de Boois H. (1993). Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone. IGBP Report, No. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Jochem F. J. (2001). Morphology and DNA content of bacterioplankton in the northern Gulf of Mexico: analysis by epifluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 25, 179–194 10.3354/ame025179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. N. (1984). Nitrate reduction by shaking with cadmium – alternative to cadmium columns. Water Res. 18, 643–646 10.1016/0043-1354(84)90215-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kana T. M., Glibert P. M. (1987). Effects of irradiances up to 2000 u-E m-2s-1 on marine Synechococcus WH7803.1. Growth, pigmentation and cell composition. Deep Sea Res. A 34, 479–495 10.1016/0198-0149(87)90002-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karl D. M. (2002). Nutrient dynamics in the deep blue sea. Trends Microbiol. 10, 410–418 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02430-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch F., Gobler C. J. (2009). The effects of tidal export from salt marsh ditches on estuarine water quality and plankton communities. Estuaries Coast 32, 261–275 10.1007/s12237-008-9123-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koch F., Marcoval A., Panzeca C., Bruland K. W., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A., Gobler C. J. (2011). The effects of vitamin B12 on phytoplankton growth and community structure in the Gulf of Alaska. Limnol. Oceanogr. 3, 1023–1034 10.4319/lo.2011.56.3.1023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. B., Bidigare R. R., Laws E., Landry M. R., Campbell L. (1999). Cell cycle and physiological characteristics of Synechococcus (WH7803) in chemostat culture. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 189, 17–25 10.3354/meps189017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen C. J. (1968). Carbon/chlorophyll relationships in an upwelling area. Limnol. Oceanogr. 13, 202. 10.4319/lo.1968.13.1.0202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medigue C., Krin E., Pascal G., Barbe V., Bernsel A., Bertin P. N., et al. (2005). Coping with cold: the genome of the versatile marine Antarctica bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125. Genome Res. 15, 1325–1335 10.1101/gr.4126905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel D. W., Spaeth J. P. (1962). Occurrance of Vitamin B12 in the Sargasso Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 7, 151–154 10.4319/lo.1962.7.2.0151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. J., Griffin L. E., Bowles K. M., Meile C., Gifford S., Givens C. E., et al. (2010). Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J. 4, 784–798 10.1038/ismej.2009.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon S. W. (1995). Coastal marine eutrophication -a definition, social causes, and future concerns. Ophelia 41, 199–219 [Google Scholar]

- Okbamichael M., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2004). A new method for the determination of Vitamin B-12 in seawater. Anal. Chim. Acta 517, 33–38 10.1016/j.aca.2004.05.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okbamichael M., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2005). Direct determination of vitamin B-1 in seawater by solid-phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography quantification. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 3, 241–246 10.4319/lom.2005.3.241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson R. J., Zettler E. R., Chisholm S. W., Dusenberry J. A. (1991). “Advances in oceanography through flow cytometry,” in Individual Cell and Particle Analysis in Oceanography, ed. Demers S. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ). [Google Scholar]

- Omori M., Ikeda T. (1984). Methods in Marine Zooplankton Ecology. New York: John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- Palenik B., Brahamsha B., Larimer F. W., Land M., Hauser L., Chain P., et al. (2003). The genome of a motile marine Synechococcus. Nature 424, 1037–1042 10.1038/nature01943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeca C., Beck A. J., Leblanc K., Taylor G. T., Hutchins D. A., Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A. (2008). Potential cobalt limitation of vitamin B-12 synthesis in the North Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22, 7. 10.1029/2007GB003124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeca C., Beck A. J., Tovar-Sanchez A., Segovia-Zavala J., Taylor G. T., Gobler C. J., et al. (2009). Distributions of dissolved vitamin B-12 and Co in coastal and open-ocean environments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 85, 223–230 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.08.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panzeca C. A., Tovar-Sanchez A., Agusti S., Reche I., Duarte C. M., Taylor G. T., et al. (2006). B Vitamins as regulators of phytoplankton dynamics. Eos (Washington DC) 87, 593–596 10.1029/2006EO520002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M. (1977). Vitamin-B12 in Lake Washington, USA-concentration and rate of uptake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 22, 527–538 10.4319/lo.1977.22.3.0527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons T. R., Maita Y., Lalli C. M. (1984). A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods for Seawater Analysis. Oxford: Pergamon [Google Scholar]

- Provasoli L., Carlucci A. F. (1974). “Vitamins and growth regulators,” in Algal Physiology and Chemistry, ed. Stewart W. D. P. (Berkeley: University of California Press; ), 741–787 [Google Scholar]

- Raux E., Schubert H. L., Warren M. J. (2000). Biosynthesis of cobalamin (vitamin B-12): a bacterial conundrum. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 1880–1893 10.1007/PL00000670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. A., Kubler J. E. (2002). New light on the scaling of metabolic rate with the size of algae. J. Phycol. 38, 11–16 10.1046/j.1529-8817.38.s1.31.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann B., Simonsen P., Stensgaard L. (1989). The carbon and chlorophyll content of phytoplankton from various nutrient regimes. J. Plankton Res. 11, 1037–1045 10.1093/plankt/11.5.1037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocap G., Larimer F. W., Lamerdin J., Malfatti S., Chain P., Ahlgren N. A., et al. (2003). Genome divergence in two Prochlorococcus ecotypes reflects oceanic niche differentiation. Nature 424, 1042–1047 10.1038/nature01947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A., Cutter L. S., Durazo R., Smail E. A., Gómez-Consarnau L., Webb E. A., et al. (2012). Multiple B-vitamin depletion in large areas of the coastal ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 14041–14045 10.1073/pnas.1208755109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanudo-Wilhelmy S. A., Gobler C. J., Okbamichael M., Taylor G. T. (2006). Regulation of phytoplankton dynamics by vitamin B-12. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, 4. 10.1029/2005GL025046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smayda T. J. (1997). Harmful algal blooms: their ecophysiology and general relevance to phytoplankton blooms in the sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42, 1137–1153 10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swift D. G. (1980). “Vitamins and growth factors,” in The Physiological Ecology of Phytoplankton, ed. Morris I. (Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; ), 329–368 [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Z., Koch F., Gobler C. J. (2010). Most harmful algal bloom species are vitamin B-1 and B-12 auxotrophs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 20756–20761 10.1073/pnas.0908007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor F. J. R. (ed.). (1987). The Biology of Dinoflagellates. Botanical Monographs. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama J. C. (1981). The simultaneous analysis of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in naturall waters. Mar. Chem. 10, 109–122 10.1016/0304-4203(81)90027-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valiela I. (2006). Global Coastal Change. Malden, MA: Blackwell [Google Scholar]

- Vishniac H. S., Riley G. A. (1961). Cobalamin and thiamine in Long Island Sound: patterns of distribution and ecological significance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 6, 36–41 10.4319/lo.1961.6.1.0036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren M. J., Raux E., Schubert H. L., Escalante-Semerena J. C. (2002). The biosynthesis of adenosylcobalamin (vitamin B-12). Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 390–412 10.1039/b108967f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welschmeyer N. A. (1994). Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll-a in the presence of chlorophyll-b and pheopigments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39, 1985–1992 10.4319/lo.1994.39.8.1985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worden A. Z., Nolan J. K., Palenik B. (2004). Assessing the dynamics and ecology of marine picophytoplankton: the importance of the eukaryotic component. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 168–179 10.4319/lo.2004.49.1.0168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]