Abstract

Background:

Reactive lesions of the oral cavity are non-neoplastic proliferations with very similar clinical appearance to benign neoplastic proliferation. This similarity is troublesome in the differential diagnosis. The aim of this study was to determine the frequency and distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions.

Materials and Methods:

The study was a retrospective archive review. The medical records of 2068 patients with histopathologic diagnosis of oral cavity reactive lesions were studied. The patients’ clinical data were registered and evaluated retrospectively. The obtained frequency of patients’ age, gender, and anatomic location were analyzed. Descriptive statistics were used for evaluating the registered data.

Results:

Peripheral giant cell granuloma was the most prevalent lesion (n=623, 30.12%). This was followed by pyogenic granuloma (n=365, 17.65%), epulis fissuratum (n=327, 15.81%), irritation fibroma (n=288, 13.93%), cemento-ossifying fibroma (n=277, 13.40%), inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia (n=177, 8.56%), and inflammatory papillary hyperplasia (n=11, 0.53%). The age ranged from 2 to 85 years, with a mean of 39.56 years. The lesions were more common in males (n=1219, 58.95%) than in females (n=849, 41.05%). Attached gingiva with 1331 (64.36%) cases was the most frequent place of reactive lesions.

Conclusion:

Peripheral giant cell granuloma was the most prevalent reactive lesion of the oral cavity. The reactive lesions were more common in males, gingival, and the third decade. Some differences have been found between the findings of the present study and previous reports.

Keywords: Hyperplastic lesions, oral cavity, reactive lesions

INTRODUCTION

Reactive lesions are tumor-like hyperplasia that are produced in association with chronic local irritation or trauma.[1] These proliferations are painless pedunculated or sessile masses in different colors, from light pink to red.[2] The surface appearance is variable from non-ulcerated smooth to ulcerated mass. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.[1] Reactive proliferations are fibrous tissues with another histologic component such as multinucleated giant cells, calcified material, or small vessels hyperplasia. Epulis is a traditional clinical name for gingival reactive proliferations. Irritation fibroma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, and cemento-ossifying fibroma are the common reactive lesions of the oral cavity.[3] Epulis fissuratum, inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia, and inflammatory papillary hyperplasia are other oral cavity reactive lesions.[1]

In different studies, the distribution data of oral reactive lesions have shown some differences in type, age, gender, and location of prevalent lesions.[4–9]

The clinical appearance of reactive lesions is very similar to that of neoplastic proliferations. This similarity is a challenging matter for differential diagnosis. Our knowledge about the distribution of lesions is a practical tool for better diagnosis. Studies about the distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions are not yet sufficient. The aim of this study was to determine the frequency and distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was retrospective archive review. The records of 2068 patients with histopathologic diagnosis of oral cavity reactive lesions were obtained from Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, from 1988 to 2005. The lesions were classified into seven groups as: peripheral giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, cemento-ossifying fibroma, epulis fissuratum, irritation fibroma, inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia, and inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. Academic oral and maxillofacial text was used for classification of reactive lesions.[1] Incomplete registered records and missed pathologic slides were the exclusion criteria. The complete medical records which had pathologic slides were included in the study. The lesions that were related to dentures were classified in epulis fissuratum group. Others with undefined clinical features were named under inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia type. Microscopic sections were examined by two pathologists. Age, gender, and anatomic location of the lesions were registered from the medical records and analyzed for each lesion. The incidences of obtained data were analyzed. The descriptive statistics were used for evaluating the registered data.

RESULTS

Peripheral giant cell granuloma was the most prevalent lesion (n=623, 30.12%). It was followed by pyogenic granuloma (n=365, 17.65%), epulis fissuratum (n=327, 15.81%), irritation fibroma (n=288, 13.93%), cemento-ossifying fibroma (n=277, 13.40%), inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia (n=177, 8.56%), and inflammatory papillary hyperplasia (n=11, 0.53%).

Age

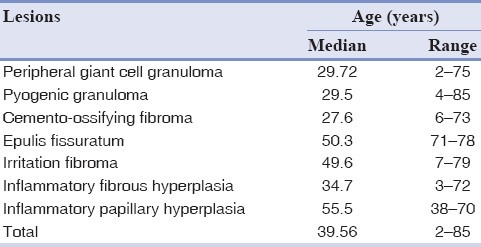

The age ranged from 2 to 85 years, with a mean of 39.56 years. Peripheral giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, and cemento-ossifying fibroma were more common in the third decade (n=1265, 61.17%). Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia was more frequent in the fourth decade (n=177, 8.56%), epulis fissuratum and irritation fibroma in the fifth decade (n=615, 29.74%), and inflammatory papillary hyperplasia in the sixth decade (n=11, 0.53%). The third decade (n=1265, 61.17%) comprised the most cases, followed by the fifth decade (n=615, 29.73%). Table 1 shows the frequency of oral cavity reactive lesions in different ages.

Table 1.

Distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions in different ages

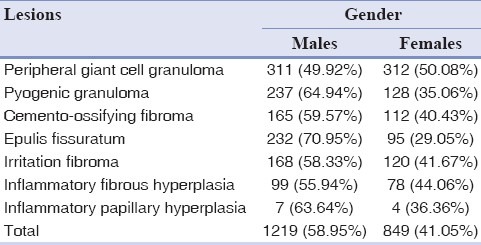

Gender

1219(58.95%) of cases were occurred in males and 849(41.05%) in females. Male to female ratio was 1.4:1. With the exception of peripheral giant cell granuloma, lesions were more common in males (n = 908, 74.48%). Table 2 shows the distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions in different genders.

Table 2.

Distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions in males and females

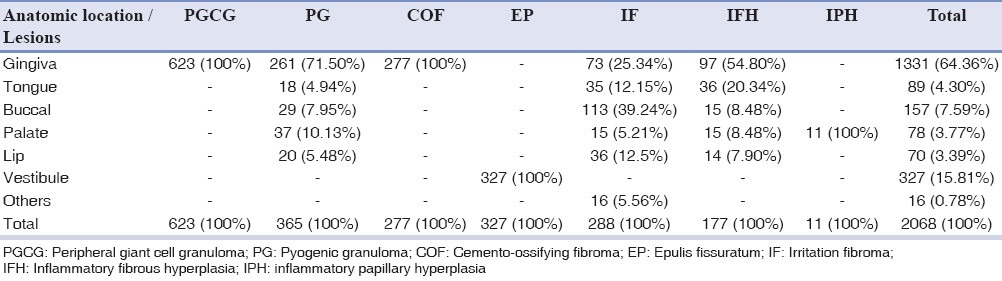

Anatomic location

Gingiva with 1331 (64.36%) cases was the most frequent place of reactive lesions, followed by vestibule [327 (15.81%)] and buccal mucosa [157 (7.59%)]. Table 3 shows the frequency of oral cavity reactive lesions in different anatomic locations.

Table 3.

Distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions in different anatomic locations

DISCUSSION

In this series of 2068 cases of oral reactive lesions, peripheral giant cell granuloma was the most common reactive lesion. The reactive lesions were more common in males, gingival, and the third decade. Reactive lesions are common tumor-like proliferations in the oral cavity. In spite of some clinical differences, their features are sometimes very similar to those of tumors. This resemblance is troublesome in the differential diagnosis. Our knowledge of reactive lesions distribution can be a useful tool for correct diagnosis.

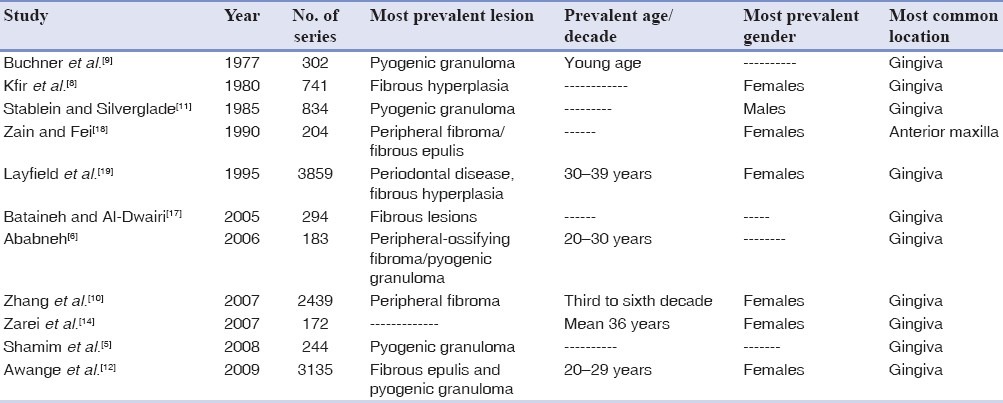

Table 4 shows the distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions in different case series studies. The results show some differences in obtained data. In the 2,439, 741, 834, and 333 case series studies about oral reactive lesions, peripheral fibroma, fibrous hyperplasia, pyogenic granuloma, and fibrous epulis have been reported as prevalent types of reactive lesions, respectively.[8,10–12] Some studies concluded that pyogenic granuloma is the most reactive oral lesion.[6,7,9,13]

Table 4.

Distribution of oral cavity reactive lesions in different case series studies

The differences are mainly due to different classifications and terminology of lesions and number of cases. We used academic oral and maxillofacial text for classification of reactive lesions.[1]

In this study, peripheral giant cell granuloma was the most prevalent lesion. This finding is not in agreement with the reports of Kfir et al.[8] and Zhang et al.[10] who found peripheral giant cell granuloma to be the least common type of oral reactive proliferation in their series.

In our series, peripheral giant cell granuloma comprised 30.12% of the total cases with 49.92% males and 50.08% females. This finding is not in agreement with those of Salum et al.[7] and Zarei et al.[14] who reported higher occurrence of peripheral giant cell granuloma in males. On the other hand, the results are in agreement with the reports of Katsikeris et al.[15] and Motamedi et al.[16] Their findings are compatible with the results of this study about patients’ gender and ages.

The report of Zarei et al.[14] is from Kerman province, so it seems that race in conjunction with other oral cavity local factors may have a causative role in reactive hyperplasia growth. Racial differences are an important factor that can influence the results. Multicentric studies are necessary for ruling out this possibility.

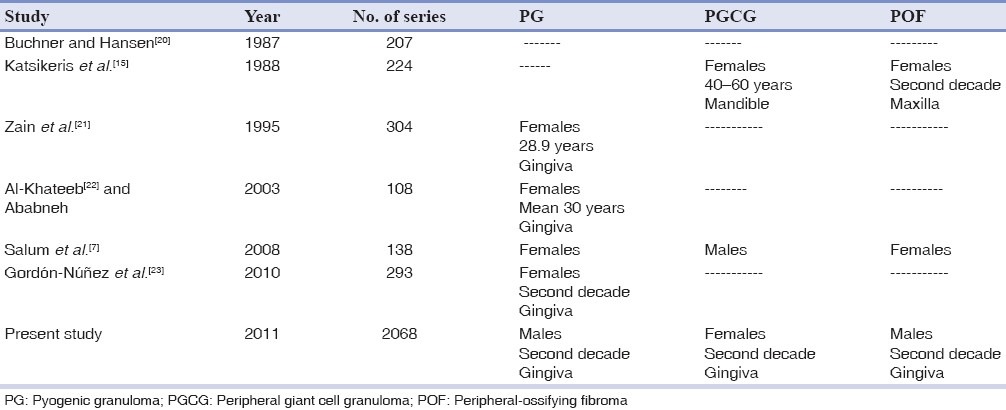

Table 5 shows the distribution of pyogenic granuloma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, and peripheral-ossifying fibroma in different case series studies in comparison with the present study . Pyogenic granuloma and peripheral-ossifying fibroma were more prevalent in females. This finding is not compatible with the finding in our series. Other results of age and gender were almost in agreement with this study.[7,15,20–23]

Table 5.

Distribution of PG, PGCG, and POF in different case series studies

We could not find any report for other reactive lesions.

In the present study, the mean age of patients was 39.56 years and the third decade was more frequently affected (61.17%), which is comparable with the findings of other studies.[10,12] This finding reflects that the factors involved in producing reactive lesions have a high influencing effect in the third decade and applying preventive methods for oral hygiene improvement is important.

In this series, the oral reactive lesions were more frequent in males (58.95%), with a male:female ratio of 1.4:1. This finding is not in agreement with other studies which have shown the higher prevalence of reactive lesions in females than males.[8,10,12,14,19] The ethnic differences between studies could be the reason for different outcomes of the reports.

In accordance with other reports, in the present study gingiva with 64.36% of the total cases was the most frequent anatomic location for oral reactive lesions.[12,17] Periodontal ligament, periostum and connective tissue are the origin of reactive lesions.[3] So, it seema that the more prevalence of these lesions in gingival can be meaningful.

Some differences have been found between the findings of this study and the previous reports. We attribute these dissimilarities to racial differences and different selected classification method. The multicentric study is a proper method for expanding our knowledge about the existing differences.

CONCLUSION

Peripheral giant cell granuloma was the most prevalent reactive lesion. The lesions were more common in males, gingival, and the third decade. Some differences have been found between the findings of the present study and previous reports. These differences may originate from ethnic dissimilarities and histopathologic case arrangement in lesions′ classification.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by Shahed University

Conflict of Interest: This study was completed by financial support of deputy of research, Shahed University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 3rd ed. China: Saunders; 2009. pp. 510–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral pathology: Clinical pathologic correlations. 5th ed. China: Saunders; 2008. pp. 156–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. pp. 278–85. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Khateeb TH. Benign oral masses in a northern jordanian population-a retrospective study. Open Dent J. 2009;28:147–53. doi: 10.2174/1874210600903010147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamim T, Varghese VI, Shameena PM, Sudha S. A retrospective analysis of gingival biopsied lesions in South Indian population: 2001-2006. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E414–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ababneh KT. Biopsied gingival lesions in northern Jordanians: A retrospective analysis over 10 years. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26:387–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salum FG, Yurgel LS, Cherubini K, De Figueiredo MA, Medeiros IC, Nicola FS. Pyogenic granuloma, peripheral giant cell granuloma and peripheral ossifying fibroma: Retrospective analysis of 138 cases. Minerva Stomatol. 2008;57:227–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kfir Y, Buchner A, Hansen LS. Reactive lesions of the gingiva.A clinicopathological study of 741 cases. J Periodontol. 1980;51:655–61. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.11.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchner A, Calderon S, Ramon Y. Localized hyperplastic lesions of the gingiva: A clinicopathological study of 302 lesions. J Periodontol. 1977;48:101–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Chen Y, An Z, Geng N, Bao D. Reactive gingival lesions: a retrospective study of 2,439 cases. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:103–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stablein MJ, Silverglade LB. Comparative analysis of biopsy specimens from gingiva and alveolar mucosa. J Periodontol. 1985;56:671–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.11.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awange DO, Wakoli KA, Onyango JF, Chindia ML, Dimba EO, Guthua SW. Reactive localised inflammatory hyperplasia of the oral mucosa. East Afr Med J. 2009;86:79–82. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v86i2.46939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anneroth G, Sigurdson A. Hyperplastic lesions of the gingiva and alveolar mucosa.A study of 175 cases. Acta Odontol Scand. 1983;41:75–86. doi: 10.3109/00016358309162306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarei MR, Chamani G, Amanpoor S. Reactive hyperplasia of the oral cavity in Kerman province, Iran: a review of 172 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:288–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsikeris N, Kakarantza-Angelopoulou E, Angelopoulos AP. Peripheral giant cell granuloma.Clinicopathologic study of 224 new cases and review of 956 reported cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:94–9. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(88)80158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motamedi MH, Eshghyar N, Jafari SM, Lassemi E, Navi F, Abbas FM, Khalifeh S, Eshkevari PS. Peripheral and central giant cell granulomas of the jaws: a demographic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bataineh A, Al-Dwairi ZN. A survey of localized lesions of oral tissues: a clinicopathological study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:30–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zain RB, Fei YJ. Peripheral fibroma/fibrous epulis with and without calcifications.A clinical evaluation of 204 cases in Singapore. Odontostomatol Trop. 1990;13:94–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Layfield LL, Shopper TP, Weir JC. A diagnostic survey of biopsied gingival lesions. J Dent Hyg. 1995;69:175–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:452–61. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zain RB, Khoo SP, Yeo JF. Oral pyogenic granuloma (excluding pregnancy tumour)-a clinical analysis of 304 cases. Singapore Dent J. 1995;20:8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Khateeb T, Ababneh K. Oral pyogenic granuloma in Jordanians: a retrospective analysis of 108 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1285–8. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00729-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordón-Núñez MA, de Vasconcelos Carvalho M, Benevenuto TG, Lopes MF, Silva LM, Galvão HC. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a retrospective analysis of 293 cases in a Brazilian population. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2185–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]