Abstract

Background:

Chlorhexidine (CHX) as a gold standard chemical agent appears to be the most effective antimicrobial agent for reduction of both plaque and gingivitis. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of two concentrations of digluconate chlorhexidine (CHX) solutions (0.12% and 0.20%) on gingival indices and the level of dental staining during 14 days.

Materials and Methods:

in this double-blind controlled clinical trial study 60 patients with moderate to severe gingivitis aged 17–56 years were randomly selected and divided to three groups: Group I (placebo) Group II (0.12% CHX), and Group III (0.2% CHX). Patients rinsed their mouthwashes twice a day after brushing. Before the examination and after 14 days plaque index, gingival index, bleeding index, and stain index were evaluated. The data were analyzed by “Mann–Whitney” test and P value was 0.05.

Results:

the results showed that plaque index and gingival index significantly reduced in Groups II and III in comparison with the placebo group (P < 0.0001). However, the two concentrations did not differ significantly from each other (P = 0.552). Same results were observed in term of gingival bleeding index with this different that 0.2% CHX was significantly more efficient than 0.12% CHX (P < 0.0001). CHX mouthrinse, both concentrations, significantly increased the dental staining level (intensity and area) in comparison with the placebo group. Remarkable difference also was seen between 2 CHX concentrations so that the 0.2% CHX caused much more staining on the teeth than 0.12% CHX.

Conclusion:

based on the results of this study we can conclude that the lower concentrations of CHX should be prescribed, decreasing side effects, since higher concentrations do not seem to be more effective in controlling dental plaque and gingivitis.

Keywords: chlorhexidine, periodontal index, staining

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease and caries are the most prevalent infectious oral diseases in human, where both are associated with dental plaque.[1–3]

The removal of plaque is the main key of prevention and the first step in treatment of periodontal disease. There are physical and chemical approaches for controlling the plaque where the former is more common and cost-effective but because of its dependence to individuals hand skill it cannot be reliable all the time,[3] so the use of chemical methods as a complementary way has been demonstrated to meet the adequate plaque control. Numerous chemical agents have been developed so far, chlorhexidine (CHX) as a gold standard appears to be the most effective antimicrobial agent for reduction of both plaque and gingivitis.[4–9] Its effectiveness can be attributed to it bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects and its substantivity within the oral cavity (8 h after rinsing).[10–13]

However, the adverse-effects of CHX limit the long-term use of this antiseptic agent and include taste alteration, excess formation of supragingival calculus, soft-tissue lesions in young patients, allergic responses, and staining of teeth and soft tissues.[14,15] This kind of discoloration especially in the interproximal areas, and tongue are often caused by a precipitation reaction between tooth-bound chlorhexidine and chromogens from food or beverages.[13,16] In a clinical-trial study conducted by Gürgan et al. in 2006, the change in color of the labial and buccal mucosa, particularly of the gingiva, after day 3 of rinsing was reported as the most commonly side effect of 0.2% alcohol-free chlorhexidine mouthrinse.[17]

A number of chlorhexidine mouthrinse products are available worldwide at concentrations between 0.1% to 0.2%; it has been shown that plaque inhibition by chlorhexidine is dose dependant; lower concentrations were found to lack plaque inhibitory properties. Although there are evidences that CHX is an effective antimicrobial agent in both concentrations, comparison of the two existing formulations is still necessary to detect the most efficient concentration that has the least side-effects.

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of two concentrations of chlorhexidine solutions (0.12% and 0.20%) on gingival indices and the level of dental staining during 14 days.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this double-blind controlled clinical trial study 60 patients aged 17–56 years were randomly selected from whom referred to Periodontology Department of Dental Clinic of Mashad University. To be included in the study patients should have gingivitis and bleeding on probing but no attachment loss or bone loss. Patients with previous or present history of periodontitis, those who were under medicine which could induce gingival overgrowth in the 60 days previous to the experiment, pregnant women, drug addicted, or any systemic condition that could negatively influence oral health have been excluded from the study. In the beginning of experimental period all participants have signed the written informed consents and then were taken under an oral examination which in through the following clinical parameters was recorded:

Plaque Index (Silness and Löe)

Gingival Index (Löe and Silness)

Bleeding Index (Ainamo and Bay)

Stain Index (Lobene)

After that a coded bottle of mouthwash was given to each patient by a nurse who was not informed about the meaning of each code either. These bottles could contain 0.12% CHX, 0.2% CHX or placebo (20 bottles of each). Patients were asked to rinse their mouthwash twice daily after brushing for 2 weeks.

In the day 14 all the mentioned clinical parameters were re-assessed by one trained experienced examiner under standard dental office and light source conditions.

The data were entered into a computer using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 15.5) software and analyzed by “Mann-Whitney” test and P value was 0.05.

RESULTS

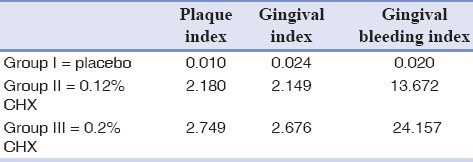

Table 1 shows the results concerning clinical parameters. The mean difference of Plaque index before and after the examination period for both groups rinsed CHX (0.2% or 0.12%) was statistically higher than the placebo group (P < 0.0001 for both CHX groups). Similar effects were found for gingival index, however, no statistically significant differences were observed between both chlorhexidine concentration regimes (P = 0.552) (Mann–Whitney test).

Table 1.

Mean differences of PI, GI, GBL of two CHX concentration and the placebo group

For gingival bleeding index, the mean difference of the group that rinsed 0.2% CHX was 24.157 that is significantly higher than 0.12% CHX group (13.672) and placebo group (0.020) (P < 0.0001).

The amount of gingival bleeding reduction in group used 0.12% CHX was also significantly more than the control group (P < 0.0001).

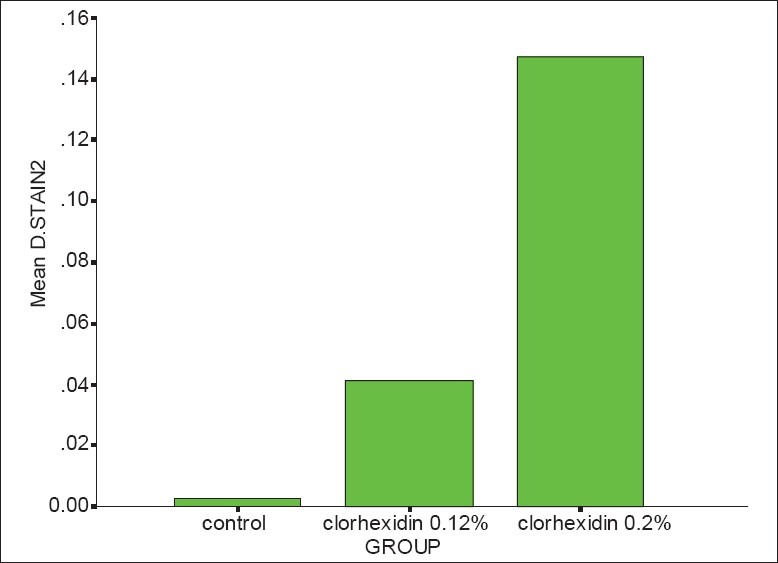

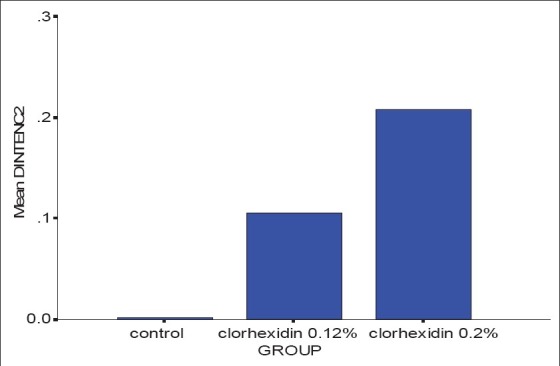

Results showed that after 14 days taking CHX the dental staining area and intensity increased significantly in comparison with the placebo group) (P < 0.0001).

Significance difference was seen between 2 CHX concentration so that the 0.2% CHX caused much more staining on the teeth than 0.12% CHX (P = 0.001) [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Mean difference of stain “area” after 14 days (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.00 < 0.05, χ2 = 30.28)

Figure 2.

Mean difference of stain “intensity” after 14 days (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.00 < 0.05, χ2 = 32.67)

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated clinically two chlorhexidine concentration regimes as adjuncts to mechanical plaque control. A randomized, cross-over, double blind design was chosen in order to generate the best possible evidence.

In this study, there were found no significant differences between 0.2% and 0.12% CHX mouth rinses in term of PI and GI that is similar to the results of previous studies. Franco et al. reported no remarked differences between both concentrations in relation to plaque and gingival bleeding.[1] Quirynen et al. demonstrated that the CHX 0.12% and the CHX 0.12% + CPC 0.05% formulations were as efficient as the CHX 0.2% mouthrinse in retarding de novo plaque formation.[15] However, in a more different study Stoeken et al. did not see 0.12% CHX as effective as 0.2%, most likely it's due to forms of CHX they used in their experiments as 0.2% CHX was applied in form of mouthrinse and 0.12% CHX as a spray.[18]

Mendieta et al. also did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between 0.12% and 0.2% chlorhexidine rinses.[19]

Lang et al. showed that gingivitis can be controlled successfully on a longitudinal basis using 0.1% or 0. 2% mouthrinses of CHX as an adjunct to daily toothbrushing.[20]

In our study, GBI found to be decreased significantly more by CHX 0.2% than 0.12% CHX that is not totally supported by the results of Franco et al. that did not observe considerable differences after 14 days. The difference in terms of gingival bleeding from these studies and the present may be due to the different design of the studies. As in Franco's study participants were submitted to professional mechanical tooth cleaning and received oral hygiene instruction at the beginning of the experiment, while in our study all participants had gingivitis at the baseline.

In term of dental staining index, clinical studies of the influence of chlorhexidine concentration on staining are few, not well controlled and contradictory.[14,21] However, Jenkins et al. obtained similar results to our study so that the lower concentrations of CHX induce significantly less dental staining.[22] Mendieta et al. reported the 0.12% chlorhexidine + fluoride products have less propensity to induce dietary staining although it appeared to cause some loss of efficacy.[19] On the other hand Lorenz et al. through an in vitro study observed that the optical density readings for specimens treated with saliva and the 0.12% chlorhexidine formulation were at most passages slightly higher than with the 0.2% formulation.[7]

The results of this study may contribute to the clinical practice in this way that the lower concentrations of CHX should be prescribed, decreasing side effects, since higher concentrations do not seem to be more effective in controlling dental plaque and gingivitis.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of this study, we can conclude that the lower concentrations of CHX should be prescribed, decreasing side effects, since higher concentrations do not seem to be more effective in controlling dental plaque and gingivitis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Mashad University of Medical Sciences Vice Chancellor for Research

Conflict of Interest: The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Franco Neto CA, Parolo CC, Rösing CK, Maltz M. Comparative analysis of the effect of two chlorhexidine mouthrinses on plaque accumulation and gingival bleeding. Braz Oral Res. 2008;22:139–44. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242008000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bossmann K. Plaque and plaque control. Oralprophylaxe. 1988;10:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg SD. Chemical control of plaque. (332-4).Dent Update. 1990;17:330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bral M, Brownstein CN. Antimicrobial agents in the prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 1988;32:217–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hase JC, Attström R, Edwardsson S, Kelty E, Kisch J. 6-month use of 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride in comparison with 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo. (I). Effect on plaque formation and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:746–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keijser JA, Verkade H, Timmerman MF, Van der Weijden FA. Comparison of 2 commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses. J Periodontol. 2003;74:214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz K, Bruhn G, Heumann C, Netuschil L, Brecy M, Hoffmann T. Effect of two new chlorhexidine mouthrinses on the development of dental plaque, gingivitis, and discolouration. A randomized, investigator-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-week experimental gingivitis study. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:561–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Strydonck DA, Demoor P, Timmerman MF, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. The anti-plaque efficacy of a chlorhexidine mouthrinse used in combination with toothbrushing with dentifrice. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:691–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang N, Brecx MC. Chlorhexidine digluconate–an agent for chemical plaque control and prevention of gingival inflammation. J Periodontal Res. 1986;21:74–89. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addy M. Chlorhexidine compared with other locally delivered antimicrobials. A short review. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:957–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornman KS. The role of supragingival plaque in the prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases. J Periodontal Res. 1986;21:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denton GW. Chlorhexidine, Disinfection, sterilization and preservation. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CG. Chlorhexidine: Is it still the gold standard? Periodontol. 2000;1997(15):55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flötra L, Gjermo P, Rölla G, Waerhaug J. Side effects of chlorhexidine mouth washes. Scand J Dent Res. 1971;79:119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quirynen M, Avontroodt P, Peeters W, Pauwels M, Cauck W, Steen Berghe D. Effect of different chlorhexidine formulations in mouthrinses on de novo plaque formation. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:1127–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.281207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addy M, Wade W, Goodfield S. Staining and antimicrobial properties in vitro of some chlorhexidine formulations. Clin Prev Dent. 1991;13:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurgan CA, Zaim E, Bakirsoy I, Soykan E. Short-term side effects of 0.2% alcohol-free chlorhexidine mouthrinse used as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A double-blind clinical study. J Periodontol. 2006;77:370–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoeken JE, Versteeg PA, Rosema NA, Timmerman MF, Van der velden U. Inhibition of “de novo” plaque formation with 0.12% chlorhexidine spray compared to 0.2% spray and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash. J Periodontol. 2007;78:899–904. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendieta C, Vallcorba N, Binney A, Addy M. Comparison of 2 chlorhexidine mouthwashes on plaque regrowth in vivo and dietary staining in vitro. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:296–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang NP, Hotz P, Graf H, Geering AH, Saxer UP, Sturzenberger OP, et al. Effects of supervised chlorhexidine mouthrinses in children.A longitudinal clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:101–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cumming BR, Loe H. Optimal dosage and method of delivering chlorhexidine solutions for the inhibition of dental plaque. J Periodontal Res. 1973;8:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1973.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins S, Addy M, Newcombe R. Comparision of two commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses: II.Effect on plaque reformation, gingivitis and tooth staining. Clin Prev Dent. 1999;11:12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]