Abstract

The clinical facts and radiologic findings are very important in the diagnostic evaluation of jaw swellings, and must be considered along with histologic findings. Osteoblastoma, an uncommon primary lesion of the bone that occasionally arises in the jaws, is one such lesion causing a localized jaw swelling. Clinically, osteoblastoma can be symptomatic or even remain symptom-free, and may be diagnosed only on routine radiographic examination. Histologically and clinically, differential diagnosis for osteoblastoma ranges from a variety of benign and malignant tumors that poses a diagnostic dilemma. Stressing the importance of the correct diagnosis of such lesions, this report discusses a case of aggressive osteoblastoma of the mandible posing as a diagnostic dilemma.

Keywords: aggressive, mandible, osteoblastoma

INTRODUCTION

Osteoblastoma is a rare benign tumor that accounts for less than 1% of all bone tumors and most commonly involves the spine and sacrum of young individuals.[1] Less than 10% of osteoblastoma are localized to skull and nearly half of these cases affecting the mandible, especially the posterior segments.[2] The first well-documented case of osteoblastoma of the jaw bones is attributed to Borello and Sedano in 1967.[3]

The osteoblastoma nomenclature has had a wide synonymy since its discovery by Jaffe and Mayer in 1932,[4] when it was named osteoblastic osteoid tissue forming tumor. Other names have been proposed, such as giant osteogenic fibroma[5] and giant osteoid osteoma.[6] In 1956, the lesion was definitely separated from osteoid osteoma and recognized as an entity by Jaffe and Lichtenstein, in separate reports, under the name of benign osteoblastoma. This is the name that has been adopted by the World Health Organization Classification of Bone Tumors and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.[7]

This central bone tumor usually occurs in young adults, with a mean age of 20 years; with a male to female ratio of 2:1.[8] The lesion is characterized clinically by pain, which is traditionally said to be unresponsive to pain and swelling at the tumor site, the duration being just a few weeks to a year or a more. Radiographically the lesion may appear as radiolucent that can be either ill or well defined containing variable amounts of mineralization.[9] Although, conventional radiography play an important role in diagnosis; however, the final diagnosis can only be confirmed after histopathological examination.

This report describes a case of aggressive osteoblastoma in posterior segment of mandible, in a 26-year old female.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year old female reported with the chief complaint of a slowly growing painful swelling with respect to right mandibular posterior region of 3 years duration. Pain associated with the swelling was mild and intermittent in nature. Extra-oral examination revealed a 3 cm × 3 cm smooth-surfaced swelling involving right body of the mandible, extending from the parasymphyseal region anteriorly to the right mandibular second molar posteriorly causing obvious facial asymmetry. Intraoral examination revealed no significant findings with intact mucosa overlying the area in question. No palpable cervical lymphadenopathy was present.

Panoramic view revealed an expansile radiolucent lesion in relation to right mandibular second molar. The lesion contained calcified mass approximating the distal root of the second molar and few radio-opaque flecks scattered within the radiolucency. The lesion was well-delineated, causing expansion and thinning of the lower border of the mandible [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Panoramic view revealed an expansile unilocular radiolucent lesion in relation to right mandibular second molar with variable amount of mineralization

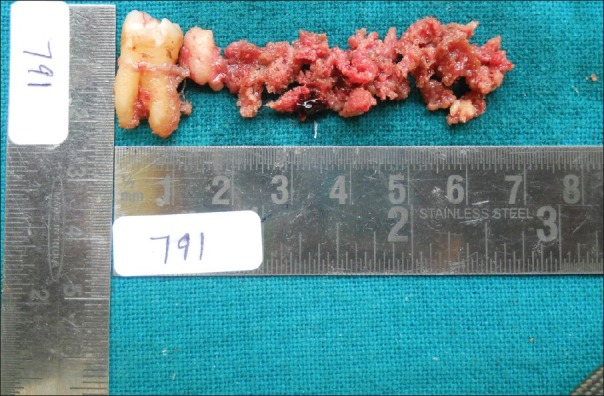

The differential diagnosis included cementoblastoma, osteoid osteoma, ossifying fibroma, and focal cemento-osseous dysplasia. Subsequently the lesion was curetted. The curettings and the second molar were submitted for the histopathological examination [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of the gross specimen showing curetted lesion along with the right mandibular second molar

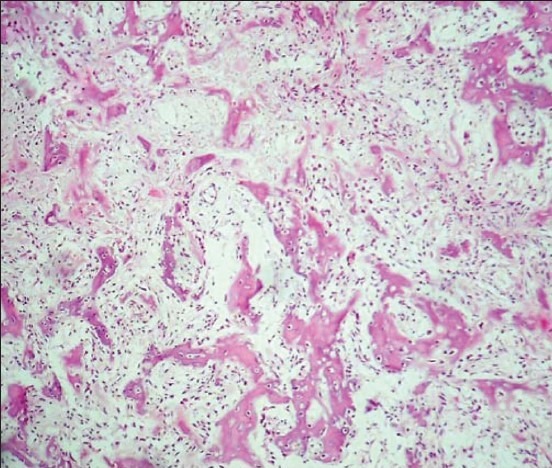

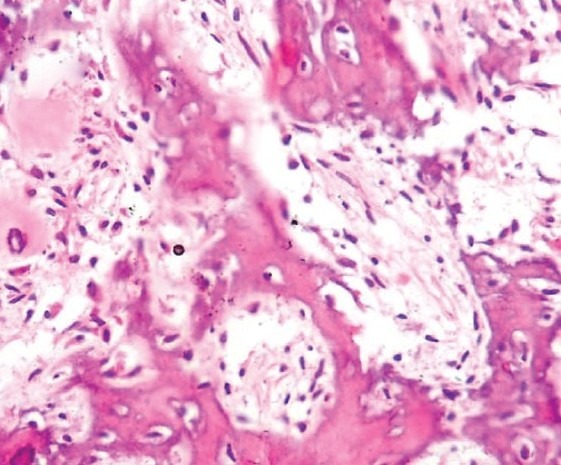

Light microscopic examination of sections stained with H-E revealed irregular wove bone like tissue within areas of hypercellular and loose fibrovascular connective tissue stroma. Large amounts of osteoid and focal areas of cementoid deposition were also seen. Woven bone showed large osteocytes within, along with a prominent plump osteoblastic rimming [Figures 3a and b]. Maturation of the trabeculae could be seen at the margin of the lesion, with appreciation of demarcation from the adjacent normal bone. The presence of multinucleated giant cells was also noted. Mitotic activity and atypical Figures were not appreciated. The histopathological features were consistent with the diagnosis of aggressive osteoblastoma.

Figure 3a.

Photomicrograph of histopathologic section reveals irregular wove bone like tissue with osteoblastic rimming within fibrovascular connective tissue stroma. (H-E stain, × 100)

Figure 3b.

Photomicrograph demonstrates presence of large and irregular areas of woven bone showing large osteocytes within, along with the presence of plump and even bizarre-appearing osteoblast-like cells, bordering the osteoid substance. (H-E stain, × 100)

DISCUSSION

Osteoblastoma is a rare bone forming tumor that very rarely involves the maxilla and mandible, particularly the posterior mandible. This diagnostic challenge may cause relevant problems with the differential diagnosis in view of the tumor's rarity, ambiguous clinico-radiologic presentation, and histopathologic features, which sometimes resemble osteosarcoma.

Conventional osteoblastomas are biologically benign with limited growth potential and typically do not exceed 4 cm in diameter. However, there is a small subgroup of borderline osteoblastomas that possesses a locally-aggressive growth pattern, usually exceeding 4 cm. These tumors cannot easily be classified as “conventional” osteoblastomas or osteosarcomas and have, thus, been separated from the classic lesion and designated as osteoblastoma-like osteosarcoma and malignant osteoblastomas or aggressive osteoblastomas.[8]

The aggressive osteoblastoma occurs in the older age group than benign osteoblastoma. On the clinical side, this tumor shows aggressive behavior.[10] It is able to extend into adjacent tissues and to recur in 10–21%, but does not metastasize. The histologic findings in the aggressive osteoblastoma are those that suggest the possibility of osteosarcoma rather than an obviously benign lesion. Some authors advocate that lesions described as aggressive osteoblastoma are, in fact, well-differentiated osteosarcomas resembling osteoblastomas. The diagnostic evaluation is based on the histologic features and the clinical behavior of the lesion.[11]

Histologically and clinically, differential diagnosis for osteoblastoma ranges from a variety of benign and malignant tumors, ranging from cementoblastoma, osteoid osteoma, fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, focal cemento-osseous dysplasia, to borderline forms of the above malignancies, up to low-grade osteosarcoma.

Benign cementoblastoma is to be considered in the differential diagnosis, since its radiographic features are similar to osteoblastoma. The feature to differentiate it from osteoblastoma, however, is the merging of the lesion and the radicular surface of the tooth.[12] In the case described here there was no contact of the tumoral mass with the tooth, in spite of their proximity. Microscopically, benign cementoblastoma and benign osteoblastoma display the same appearance. This microscopic similarity indicates that a lesion should not be diagnosed as benign cementoblastoma unless it adheres to the tooth.

Another diagnostic pitfall in connection with the benign osteoblastoma is the possibility of its confusion with osteoid osteoma. On the clinical side, the benign osteoblastoma does not tend to produce pain, so characteristic of osteoid osteoma. Also, osteoblastoma is a larger lesion, which by definition exceeds 1 cm in its greatest diameter and is not generally associated with outstanding bony sclerosis typical of osteoid osteoma.[13,14] At microscopic examination, the bony trabeculae of osteoblastoma are slightly wider than those of osteoid osteoma and there is less irregularity in their arrangement; the number of osteoblasts is much greater in osteoblastoma but osteoid osteoma lacks giant cells and is not as well vascularized as osteoblastoma.[13,15]

Histopathologically, ossifying fibroma and fibrous dysplasia of bone may share many similarities with osteoblastoma but usually are less mineralized lesions, revealing fine calcifications rather than large clusters of mineralized material. In addition, fibrous dysplasia is less circumscribed radiologically than osteoblastoma and may be multifocal, a feature that is exceedingly rare for osteoblastoma.[1]

Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia is a fibro-osseous lesion that may share similar radiographic features with osteoblastoma. Nevertheless, the former is typically asymptomatic and does not typically expand the cortex. Most lesions are smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter.[16] Although microscopically, both may feature immature bone; focal cemento-osseous dysplasia lacks a large number of plump and actively proliferating osteoblasts.

Histologic examination is paramount in confirming a definitive diagnosis and excluding osteosarcoma, especially the osteoblastic variant. The confusion arises mainly due to the presence of plump or even bizarre-appearing osteoblast-like cells in osteoblastoma, often bordering osteoid substance, mimicking the atypical cells that characterize osteosarcoma. In such instances, the diagnosis is greatly facilitated by the accurate interpretation of the histologic features in view of the radiologic findings that do not disclose the aggressive characteristics of osteosarcoma. Bertoni et al.[17] believe that the chief microscopic features that separate osteosarcoma from osteoblastoma is the lack of tumor maturation at the margins of osteosarcoma, with permeation of tumor into adjacent tissues, in contrast to maturation at the margins and lack of permeation into the adjacent bone.

Further, in view of the purported benign nature of this tumor, conservative surgical excision is the treatment of choice; because recurrence is a rare event (13.6%) and usually attributable to incomplete excision.[1] Moreover, apparently no special histological features exist that provide clues to the biological behavior of this neoplasm. Based on these various reports and findings, it is clear that the neoplasm has no constant behavior, and varies from case to case.

CONCLUSION

The importance of conceiving the individual bone tumors as clinicopathologic entities should be pointed out again. In the delineation of differential entities, the clinical facts and radiologic findings are very important in the diagnostic evaluation of the lesion, and must be considered along with the histologic findings. At the same time, adequate representative sections of the entire lesion must be submitted to ensure adequate histologic diagnosis so that appropriate treatment can be instituted to the specific pathology.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Capodiferro S, Maiorano E, Giardina C, Lacaita MG, Muzio LL, Favia G. Osteoblastoma of the mandible: Clinicopathologic study of four cases and literature review. Head Neck. 2005;27:616–21. doi: 10.1002/hed.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirra JM, Picci P, Gold RH. Bone tumors. Clinical, radiologic and pathologic correlations. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1989. pp. 389–430. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borello ED, Sedano HO. Giant osteoid osteoma of the maxilla. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;23:563–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(67)90334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe HL, Mayer L. An osteoblastic osteoid tissue-forming tumor of a metacarpal bone. Arch Surg. 1932;24:550–64. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein L. Classification of primary tumors of bone. Cancer. 1951;4:335–41. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195103)4:2<335::aid-cncr2820040219>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlin DC, Johnson EW. Giant osteoid osteoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36:559–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capelozza ALA, Dezotti MSG, Alvares LC, Fleury RN, Sant’Ana E. Osteoblastoma of the mandible: Systematic review of the literature and report of a case. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2005;34:1–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/24385194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angiero F, Mellone P, Baldi A, Stefani M. Osteoblastoma of the jaw: Report of two cases and review of the literature. In Vivo. 2006;20:665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cawson RA, Binnie WH, Speight PM, Barett AW, Wright JM. Lucas's pathology of tumors of the oral tissues. 5th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forest M. Orthopedic Surgical Pathology: Diagnosis of tumors and pseudotumoral lesions of bone and joints. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. pp. 91–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivkovic T, Vuèkovic N, Gajanin R, Karalic M, Stojiljkovic B, Panjkovic M, et al. Benign osteoblastoma of the mandible. Arch Oncol. 2000;8:73–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slootweg PJ. Cementoblastoma and osteoblastoma: A comparison of histologic features. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:385–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverberg SG. Principles and Practice of Surgical Pathology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. p. 410. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins S. Pathologic basis of disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Sunders Company; 1994. p. 1234. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helliwell TR. in the series Major problems in pathology. 1st ed. Vol. 37. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 1999. Pathology of Bone and Joint Neoplasms; pp. 169–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 2004. p. 557. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colm JS, Abrams BM, Waldron AC. Recurrent osteoblastoma of the mandible: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;46:881–5. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]