Abstract

Primary oral melanoma is a rare neoplasm of melanocytic origin, accounting for 0.5% of all oral malignancies. The “chameleonic” presentation of a mainly asymptomatic condition, rarity of this lesion, poor prognosis, and the necessity of a highly specialized treatment are factors that should be seriously considered by the involved health provider. Here is a case report presenting a malignant melanoma of oral mucosa in 48-year-old male patient on maxillary gingiva. The lesion was removed by partial maxillectomy and patient is disease free after 11 months of regular followup. This case provides an example of how dental clinicians play a major role in the identification of pigmented lesions of oral cavity and also emphasize on the fact that any pigmented lesion detected in the oral cavity may exhibit potential growth and should be submitted to biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Keywords: Gingiva, metastasis, oral melanoma, recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Oral melanoma is an extremely rare tumor arising from uncontrolled growth of melanocytes found in the basal layer of oral mucous membrane. Its incidence varies from 0.2% to 8% of all melanomas.[1] It occurs between 30 and 90 years of age, with a higher incidence in the 6th decade with a mean age of 56 years.[2] It is having a higher prevalence in yellows, blacks, Japanese, and Indians of Asia due to more frequent finding of melanin pigmentation in oral mucosa of these races. Green et al.[3] described criteria for diagnosis of Primary oral melanoma which includes demonstration of melanoma in the oral mucosa, presence of junctional activity, inability to demonstrate extraoral primary melanoma.

A total of 80% to 90% of oral malignant melanoma arises in the mucosa of maxillary jaw with a majority occurring on the keratinized mucosa of hard palate and gingiva. The other sites are mandibular gingiva, buccal mucosa, and floor of mouth.[4] Clinically, it is easy to diagnose them as these are pigmented ones and have irregular shape and outline. These are mostly asymptomatic and detected only when there is ulceration or hemorrhage of the overlying epithelium. The delayed detection may be the cause for the poor prognosis with a 5-year survival being between 15% and 38%.[5] The purpose of this article is to present a case of oral malignant melanoma, as well as to emphasize the necessity for early recognition and treatment of this lesion.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old male patient reported to the department of oral medicine and diagnosis with chief complaint of pain and swelling in the upper right gums. The patient noticed the nodule some 2 months back and pain since 2 weeks. The patient had a habit of smoking but had no familial cancer background. The clinical examination revealed a large mass of 8 × 3 cm in dimension on buccal aspect of right maxillary alveolus involving marginal, attached, and interdental gingiva [Figure 1]. The growth was blackish gray with intact surface. The margins were well defined. Anteriorly, it extends from the gingiva of mesial surface of 22, to the gingiva in relation to 17 posteriorly. Superiorly, the lesion extended to involve the upper buccal vestibule. Medially, it extended to involve the palatal mucosa. 13 was missing and 12 was displaced laterally; while, 11, 12, and 21 exhibited mobility.

Figure 1.

Primary oral malignant melanoma extending from 22 to distal aspect of 17

The palpatory findings revealed a firm consistency of lesion with mild pain. The regional lymph nodes were non-palpable. A complete examination of the lesion was done and no other primary site of the lesion was found. Correlating all clinical features, diagnosis of primary malignant melanoma of oral cavity was made and the patient was referred for further investigations. The radiographic features showed no evidence of destruction of underlying bone. A computed tomography examination of neck, chest, abdomen, and bone scanning and ultrasounds of liver and kidney were normal excluding any diagnosis of distant metastasis.

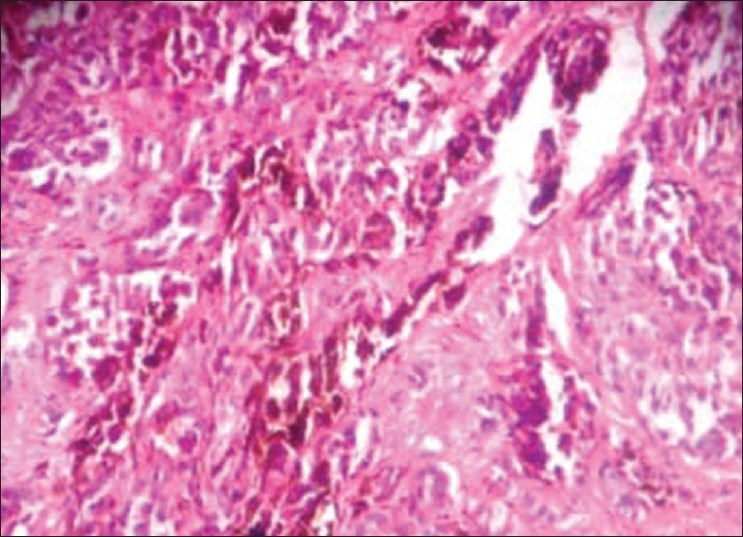

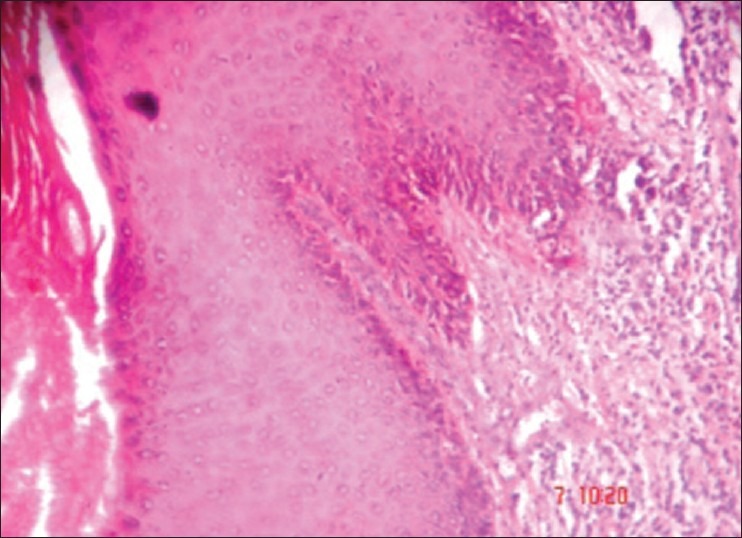

An incisional biopsy was done for the lesion under local anesthesia and the specimen was sent for histopathologic examination. The gross examination of tissue revealed a mass of 2 mm × 3 mm × 1 mm in size, which was black in color and firm in consistency. The hematoxylin and eosin-stained section showed a melanin-producing tumor, consisting of atypical irregularly elongated spindle and oval-shaped melanocytes, exhibiting uniformly dark, enlarged and irregular nuclei [Figure 2]. In the superficial layers of the tissue, a junctional nevus with pigmentation was found [Figure 3]. The diagnosis of an invasive melanoma arising most likely from a pre-existing junctional nevus was made and the patient was referred to the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic for required therapy. As per the traditional approach, partial maxillectomy of the right side was performed. To reduce the defect and to reconstruct alveolus, microvascular fibula flap was used. The orbital floor near to maxilla was reconstructed with the help of premolded titanium mesh. The open connection between the nasal and oral cavities was treated with removable prosthesis. The histologic examination of the specimen confirmed the initial diagnosis of an invasive melanoma of the oral mucosa. The underlying bone was intact. The patient has been followed-up with no evidence of recurrence or metastasis either clinically or radiographically, 11 months after the tumor's resection.

Figure 2.

The hematoxylin and eosin–stained section shows melanoma with invasive pattern showing large cells with pleomorphic vesicular nucleus and brown pigment (×40)

Figure 3.

The hematoxylin and eosin–stained section shows stratified squamous keratinized epithelium with in situmelanotic pigment growth (×10)

DISCUSSION

Mucosal melanoma of the oral cavity is a rare malignancy. It has no known predisposing factors and is difficult to diagnose and manage. Differentiating it from a metastatic melanoma is often challenging.[6] The first symptoms of oral melanoma described by Berthelsen were those of asymptomatic swelling and occasional bleeding, where he found that only 2 (14%) patients had a pain. Because most of the melanomas are painless in their early stages, the diagnosis is often unfortunately delayed until symptoms resulting from ulceration, growth, or bleeding are noted. The pain may be the later manifestation in melanoma as in our case that again could cause delay in seeking treatment.

On gross appearance, the tumors on the palate are usually flat, with a varying degree of thickness. The color is usually dark blue black. Microscopically, the tumor cells present themselves as densely packed, large epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. The melanin pigment, which is located intra or extracellularly, may be abundant, but may be sparse or even absent at the light microscopic level. The prognostic value of various levels of invasion, as established in the Clark's classification, does not apply for mucosal melanoma because of the absence of histologic landmarks, which are analogous to the papillary and reticular dermis. The staging systems that are applied to cutaneous melanoma are not applicable to mucosal melanomas. The American Joint Committee on Cancer does not have published guidelines on the staging of oral malignant melanomas. The generally followed guideline is a clinical classification stage I—clinically localized disease, stage II—regional lymph node disease, and stage III-distant disease. The tumor thickness is a reliable prognostic indicator for survival. In this case, the patient was in stage I.[7]

Westbury describes a clinical classification as follows: 1—only primary tumor present, and 2—metastasis present, 2a—adjacent skin involved, 2b—adjacent lymph nodes involved, and 2ab—adjacent skin and lymph nodes involved. This patient falls into classification 1 because adjacent skin was not involved.[8] Thus, according to these systems specification, our patient was in stage I.

The etiology of malignant melanoma is essentially unknown. Tobacco use and chronic irritation from ill-fitting dentures have been considered as possible risk factors, but the evidence is weak. The ingested and inhaled environmental carcinogens at high body temperature may play some role.[9,10] The cause could also be related to our patient as he was having the history of smoking from last 15 years. But most of the malignant melanomas arise de novo, from apparently normal mucosa, and about 30% are preceded by oral pigmentations for several months or even years. Some melanoma-associated antigens become expressed during transformation process from a benign melanocytic nevus to melanoma; the majorities of these are related to the melanin production process and most are HLA restricted. The p53 alterations have been identified in two-thirds of oral malignant melanomas. A recent study demonstrates that the loss of heterozygosity at 12p13 and p27KIP1 protein expression contributes to melanoma progression. Cytogenetic analysis and evaluation of melanocyte-specific gene-1 (MSG-1) appears to be very helpful for understanding the pathogenesis of oral malignant melanoma.[9]

The current guidelines for the surgical management of primary cutaneous melanoma recommend a diagnostic excisional biopsy of the lesion followed by a wide local excision where the diagnosis is proved.[11] However, in oral cavity, the size of the lesion or anatomic limitations, particularly the presence of teeth, may preclude the taking of excisional biopsy. Younes et al. proposed to take an excisional biopsy with a 1–2 mm margin for small lesions in amenable locations, but incisional biopsy, through the thickest or the most suspicious part of the tumor, in case of a large lesion or a location in sites where an excisional procedure would involve extensive and militating surgery.[12]

Usually oral malignant melanoma can be diagnosed with confidence on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. If pigment is completely absent (amelanotic melanoma), immunohistochemical stains are of significant help. Useful markers include S-100 protein, gp 100 (HMB-45), and Mart-1 (Melan-A).

It has always been suggested that cutting into malignant neoplasm during incisional biopsy could result in accidental dissemination of malignant cells within adjacent tissues or blood or lymphatic stream with subsequent risk of local recurrence or regional or distant metastasis. Rampen et al. and Austin et al. did find a somewhat reduced survival rate in patients with melanoma who had incisional biopsies but against the studies done by Lederman and Sober where they found no correlation in patient's prognosis with incisional and excisional biopsies. Recurrences may occur even after 10–15 years after primary therapy. Distant metastasis to the lungs, brain, liver, and bones are frequently observed.[10]

The treatment of oral malignant melanoma is still controversial and there is no census regarding the best therapeutic approach. Data from several studies indicate radical resection of the primary as the treatment of choice. Surgery should be combined with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy.[13]

Regression in melanoma is a well-recognized phenomenon and may account for many of the cases of metastatic melanoma with occult primaries. Partial regression of melanoma is relatively common, but complete regression is quite rare and relatively few cases are well documented.[14] A further feature of regression is its association with poor rather than a good prognosis. The rather nonspecific features of regressed melanoma (apparently inflammatory nodules, depigmented patches, and flat or slightly depressed scars) are easily missed or discounted unless the patient had noticed the regression.[15]

From the prognostic point of view, clinical stage at presentation is probably the most important factor in determining the outcome. It has been found by Liu et al. that thickness of the tumor, cervical lymph node metastasis, presence or absence of ulceration, and the anatomic sites are all independent risk factors. It has been calculated that nodal metastasis reduces the mean survival time from 46 to 18 months. Furthermore, a tumor thickness greater than 5 mm, presence of vascular invasion, necrosis, polymorphous tumor cell morphology, and inability to properly resect the lesion with negative margins have been associated with poor survival in patients with primary melanomas of head and neck region.[16]

CONCLUSION

Despite the improvement of surgical techniques and the introduction of new chemotherapeutic agents, prognosis of this malignancy remains poor. The generally advanced stage of the tumor at initial diagnosis leads to a poorer survival of patients with mucosal melanomas as compared with patients with cutaneous melanomas and presence of vertical growth phase are associated with median survival rate. Analysis of published cases and recognition of new ones may be helpful in establishing definite classification and proposing clinical features that would facilitate its early diagnosis as a prerequisite for timely treatment and better prognosis of this rare pathology.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patton LL, Brahim JS, Baker AR. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the oral cavity.A retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:51–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delgado Azañero WA, Mosqueda Taylor A. A practical method for clinical diagnosis of oral mucosal melanomas. Med Oral. 2003;8:348–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manganaro AM, Hammond HL, Dalton MJ, Williams TP. Oral melanoma: Case reports and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:670–6. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene GW, Haynes JW, Dozier M, Blum Beg JM, Bernier JL. Primary malignant melanoma of oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6:1435–43. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(53)90242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green TL, Greenspan D, Hansen LS. Oral melanoma report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;113:627–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1986.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Waal RI, Snow GB, Karim AB, van der Waal I. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: A review of eight cases. Br Dent J. 1994;176:185–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthelson A, Andersen AP, Jensen TS, Hansen HS. Melanomas of mucosa in the oral cavity and upper respiratory passages. Cancer. 1984;54:907–12. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<907::aid-cncr2820540526>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westbury G. Malignant melanoma of skin. In: Lumley J, Cravin J, editors. Surgical Review. Vol. 1. London: Pitman Medical; 1979. pp. 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad ML, Jungbluth AA, Patel SG, Iversen K, Hoshaw-Woodard KJ, Busam KJ. Expression and significance of cancer testis antigens in primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2004;26:1053–7. doi: 10.1002/hed.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meleti M, Leemans CR, Mooi WJ, Vescovi P, van der Waal I. Oral malignant melanoma: A review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts DL, Anstey AV, Barlow RJ, Cox NH, Newton Bishop JA, Corrie PG, et al. UK. guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Younes MN, Myers JN. Melanoma of the head and neck: Current concepts in staging, diagnosis and management. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2004;13:201–29. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3207(03)00125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lengyel E, Glide K, Remenar E, Esik O. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03033707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JL, Stehlin JS. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanoma with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399–415. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196511)18:11<1399::aid-cncr2820181104>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avril MF, Charpentier P, Margulis A, Guillanme JC. Regression of primary melanoma with metastasis. Cancer. 1992;69:1377–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920315)69:6<1377::aid-cncr2820690613>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguas SC, Quarracino MC, Lence AN, Lanfranchi-Tizeira HE. Primary melanoma of the oral cavity: Ten cases and review of 177 cases from literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:265–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]