Abstract

Aim:

Flowers of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis Linn (Malvaceae) popularly known as “China-rose flowers” contain flavonoids. Flavonoids have been found to have antidepressant activity. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the antidepressant activity of flavonoids in H. rosa-sinensis flowers with possible involvement of monoamines.

Materials and Methods:

Anti-depressant activity of methanol extract containing anthocyanins (MHR) (30 and 100 mg/kg) and anthocyanidins (AHR) (30 and 100 mg/ kg) of H. rosa-sinensis flowers were evaluated in mice using behavioral tests such as tail suspension test (TST) and forced swim test (FST). The mechanism of action involved in antidepressant activity was investigated by observing the effect of extract after pre-treatment with low dose haloperidol, prazosin and para-chlorophenylalanine (p-CPA).

Results:

Present study exhibited significant decrease in immobility time in TST and FST, similar to that of imipramine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) which served as a positive control. The extract significantly attenuated the duration of immobility induced by Haloperidol (50 μg/ kg, i.p., a classical D2-like dopamine receptor antagonist), Prazosin (62.5 μg/kg, i.p., an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist) and p-chlorophenylalanine (100 mg/kg, i.p., × 3 days; an inhibitor of serotonin synthesis) in both TST and FST.

Conclusion:

It can be concluded that MHR and AHR possess potential antidepressant activity (through dopaminergic, noradrenergic and serotonergic mechanisms) and has therapeutic potential in the treatment of CNS disorders and provides evidence at least at preclinical levels.

KEY WORDS: Anthocyanidins, dopamine, flavonoids, quercetin, serotonin

Introduction

Depression constitutes the second most common chronic condition in clinical practice[1] and will become the second leading cause of premature death or disability worldwide by the year 2020.[2] Reduced monoamine signaling and monoamine metabolite levels have been found in cerebrospinal fluid of depressed individuals; likewise serotonin, norepinephrine or dopamine depletion exerts pro-depressive effects.[3,4] In case of depression, the level of monoamine oxidase enzyme in brain is increased, which in turn reduces levels of monoamines.[5,6]

Flowers of H. rosa-sinensis Linn (Malvaceae) are reported to possess cardio- protective,[7] hypotensive,[8] antidiabetic,[9] anticonvulsant[10] and antioxidant activity.[11] These flowers are known to contain flavonoids like anthocyanin and quercetin.[12] Flavonoids have been implicated in antidepressant activity[13,14] and anxiolytic activity.[15,16] Therefore, the present research was aimed to evaluate the effect of methanol extract containing anthocyanins (MHR) and anthocyanidins (AHR) in tail suspension test (TST) and forced swim test FST.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Swiss Albino mice (22 ± 2 g) were used for this study. Mice were procured from Bharat Serum and Vaccine Ltd, Thane. The animals were housed at 24 ± 2°C and relative humidity 55 ± 5 with 12:12 h light and dark cycle. They had free access to food and water ad libitum. The animals were acclimatized for a period of seven days before the study. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animals Ethics Committee (IAEC) of MGV's Pharmacy College, Nasik.

Drugs and chemicals

Prazosin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), p-CPA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), Imipramine (Diamin, Reliance Formulation Pvt. Ltd., India), Haloperidol (Serenec, Searl, India) were used for this study.

Plant material and extraction

Flowers of H. rosa-sinensis were collected from Aushadhi Bhavan, Ayurved Seva Sangh, Nasik and authenticated by Dr. P. G. Diwakar, Joint director, Botanical Survey of India, Pune. A voucher specimen has been retained there (PASHIR-1). The methanolic extract (MHR) was obtained by maceration of fresh sepal-less flowers of H. rosa-sinensis for 72 h, followed by filtration and concentrated to remove methanol. The anthocyanidins (AHR) were extracted by a slight modification of method described earlier by Harborne.[17] Fresh sepal-less flowers (200 g) of H. rosa-sinensis were macerated in 2 L methanol: 2M HCl (85:15 v/v) solution for 72 h.[18] The extract was then concentrated to 500 ml and filtered. To the filtrate, 100 ml concentrated HCl was added. Mixture was heated in round bottom flask under reflux for 2 h. The mixture was then refrigerated until crystals of anthocyanidins (AHR) were separated out. The crystals were then filtered, air dried and stored in amber colored bottle.

Phytochemical analysis

Phytochemical analysis of MHR and AHR was carried out according to methods described earlier.[19]

Identification of anthocyanin and anthocyanidins in H. rosa sinensis

UV-visible spectra- AHR revealed peak at 286.50 nm and 537 nm while MHR revealed peak at 287.50 nm and 576 nm when spectra was run using Shimadzu-2450.

FTIR- AHR depicted presence of functional groups like phenolic –OH (1205.55 cm-1), aromatic C-C stretching (1510.10 cm-1), OH-bend and C=O stretching (1332.086 to 1446.66 cm-1), 6-member ring with carbonyl group (1612.54 cm- 1).

MHR exhibited presence of aromatic C-C stretching (1618.33 cm-1), OH-bend and C=O stretching (1278.85 cm-1) with Shimadzu-FTIR 8400S.

Antidepressant-like activity

On the day of experiment, the animals (n = 6) were divided into control and experimental groups. Control group received 0.1% CMC (carboxy-methyl cellulose), p.o., 1 h before experiment. Imipramine (10 mg/kg, i.p) was administered to animals 30 min before experiment. AHR (30 and 100 mg/kg) was suspended in 0.1% CMC and MHR (30 and 100 mg/kg) was dissolved in water and administered orally to animals 1 h before the test. The antidepressant-like activity was evaluated using tail suspension test (TST) and forced swim test (FST).

Tail suspension test

Mice were suspended on the edge of a table 58 cm above the floor by the adhesive tape placed approximately 2-3 cm from the tip of the tail. Immobility time was recorded during 5 min period. Animal was considered to be immobile when it does not show any movement of body and remain hanging passively.[20]

Despair swim test

Mice were forced to swim individually in a glass jar (25 × 12 × 25 cm3) containing fresh water of 15 cm height and maintained at 25° C. After an initial period of vigorous activity, each animal assume a typical immobile posture. A mouse was considered to be immobile when it remains floating in the water without struggling, making only minimum movements of its limbs necessary to keep its head above water. The total duration of immobility was recorded during the 5 min test. The change in immobility duration was studied after administering drugs in separate groups of animals.[21]

Involvement of neurotransmitters

Probable involvement of dopamine, adrenaline and serotonin in antidepressant-like activity of MHR and AHR was evaluated using animals pre-treated with Haloperidol (50μg/ kg, i.p.), Prazosin (62.5 μg/kg, i.p) and p-CPA (100 mg/kg, i.p.).[22] The study was performed according to Irwin schedule[23] and doses were selected from pilot studies performed in our lab. Haloperidol, Prazosin, p-CPA were administered intraperitoneally in a fixed volume of 1 ml/100 g body weight. Haloperidol and Prazosin were administered 30 min before treatment with MHR and AHR. p-CPA was administered for three consecutive days before treatment with MHR and AHR. On third day, animals received MHR and AHR 30 min after treatment with p-CPA. Duration of immobility was measured 30 min after treatment with MHR (30 and 100 mg/kg, p.o.) and AHR (30 and 100 mg/kg, p.o.).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was carried out by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. The values were significant at P < 0.05 when compared with control group.

Results

From phytochemical analysis, MHR and AHR revealed presence of flavonoids, saponins, cardiac glycosides and phenols. Spectroscopic data confirmed presence of anthocyanins and anthocyanidins like quercetin.

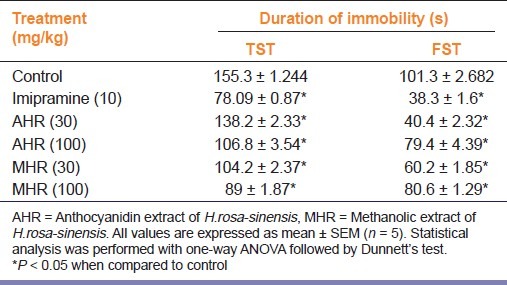

In TST and FST, MHR and AHR (30 and 100 mg/kg, p.o.) decreased the immobility periods significantly (P < 0.05) compared to vehicle treated group [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of H.rosa-sinensis extract on duration of immobility

Haloperidol (50 mcg/kg, i.p.) alone significantly (P < 0.05) increased the immobility period when compared to the vehicle treated group. Treatment of animals with MHR and AHR (30 and 100 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly reversed the increased immobility time observed after treatment with Haloperidol [Table 2].

Table 2.

Effect of low dose Haloperidol pre-treatment on antidepressant activity of H. rosa-sinensis

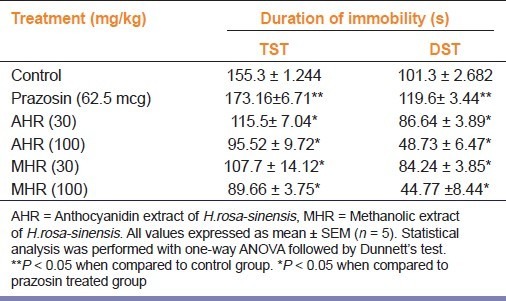

Prazosin (62.5 mcg/kg, i.p.) alone significantly (P < 0.05) increased the immobility period when compared to the vehicle treated group. Treatment of animals with MHR and AHR (30 and 100 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly reversed the increased immobility time observed after treatment with Prazosin in TST and FST [Table 3].

Table 3.

Effect of low dose Prazosin pre-treatment on anti-depressant activity of H. rosa-sinensis

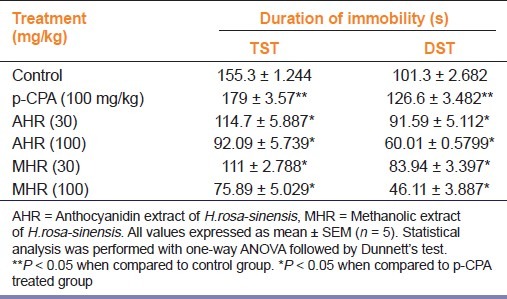

p-CPA (100 mg/kg, i.p.) alone significantly (P < 0.05) increased the immobility period when compared to the vehicle treated group, whereas, after treatment with MHR and AHR (30 and 100 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly reversed the increased immobility time observed after treatment with p-CPA in TST and FST [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effect of p-CPA pre-treatment on anti-depressant activity of H. rosa-sinensis

Discussion

Tail suspension test represents the behavioral despair model, claimed to reproduce a condition similar to human depression. Remarkably, TST detects the anti-immobility effects of a wide array of antidepressants, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), electro-convulsive shock (ECS) and even atypical antidepressants.[24]

The immobility displayed by rodents when subjected to unavoidable stress such as forced swimming is thought to reflect a state of despair or lowered mood, which are thought to reflect depressive disorders in humans which is reduced by treatment with antidepressant drugs.[20,25]

The monoamine theory of depression proposes that “depression is due to a deficiency in one or another of three monoamines, namely serotonin, noradrenaline and or/dopamine”.[26] In support to monoamine hypothesis, Haloperidol (classical D2-dopamine receptor antagonist) pre-treated group exhibited significant increase in duration of immobility which was reduced by treatment with MHR and AHR, suggesting involvement of dopamine in antidepressant-like activity of MHR and AHR.

Prazosin(an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist) also may act in CNS to suppress sympathetic outflow.[27] Porsolt et al. in 1977[21] proposed behavioral model of FST for the screening of new antidepressant compounds. In agreement with this information, in the present study, effect of MHR and AHR was investigated for Prazosin (62.5 μg/kg, i.p.) pre-treatment. Prazosin pre-treatment exhibited significant increase in duration of immobility in FST and TST which was reduced by treatment with MHR and AHR, suggesting involvement of adrenaline in antidepressant-like activity of MHR and AHR.

p-CPA inhibits synthesis of serotonin by inhibiting selectively and irreversibly enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase. Serotonin depletion is one of the factor for development of depression. p-CPA (100 mg/kg, i.p., × 3 consecutive days) treatment exhibited significant increase in duration of immobility which was blocked by treatment with MHR and AHR.

Recently, several studies have suggested the antidepressant effect of quercetin glycosides such as hyperoside, isoquercitrin and rutin using the positive results of FST.[13,14,28] Previous studies on H. rosa-sinensis revealed presence of quercetin and cyanidin flavonoids[12] which was confirmed by UV, IR studies. It was reported that, anthocyanin and their aglycones (anthocyanidins) are characterized by two absorption bands, one in the UV region (275-280 nm) and the other in the visible region (475-560 nm) and cyanidin group shows absorbance maxima at 535 nm.[29] Results from previous workers[30] also showed that cyanidin absorbs at 280 nm and 530 nm which is in accordance with the spectroscopic analysis in this study. The IR spectrum of H. rosa sinensis flowers showed characteristic absorption bands at 3421 (OH) and 1710 (C=O) cm-1.[8]

Thus, the activity of H.rosa-sinensis extract may probably involve one of the mechanisms as described above.

Conclusion

The finding of the present investigation suggests that antidepressant-like effect of H. rosa-sinensis is mediated through dopaminergic, adrenergic and serotonergic mechanisms. In our further study, we will try to explore selective mechanism of action of H. rosa-sinensis flowers responsible for antidepressant-like activity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. WHO Director-General unveils new global strategies for mental health. Press Release WHO/99-67 1999; http://www.who.int/inf-pr-1999/en/pr99-67.html .

- 3.Leonard BE. Evidence for a biochemical lesion in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutt DJ. The neuropharmacology of serotonin and noradrenaline in depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:S1–12. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200206001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esel E, Kose K, Turan MT, Basturk M, Sofuoglu S. Monoamine oxidase-B activity in alcohol withdrawal of smoker: Is there any relationship with aggressiveness. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:272–6. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan SL, Xie J, Qian FG, Wang J, Shao YC. Antidepressant amides from Piper laetispicum C. DC. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2005;40:355–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauthaman KK, Saleem MT, Thanislas PT, Prabhu VV, Krishnamoorty KK, Devraj NS. Cardioprotective effect of the Hibiscus rosa-sinensis flowers in an oxidative stress model of myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury in rat. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;20:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddiqui AA, Wani SM, Rajesh R, Alagarsamy V. Phytochemical and pharmacological investigation of flowers of H. rosa sinensis Linn. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2006;68:127–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkatesh S, Thilagavthi J, Shyam Sundar D. Antidiabetic activity of flowers of Hibiscus rosa sinensis. Fitoterapia. 2008;79:79–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasture VS, Chopde CT, Deshmukh VK. Anticonvulsive activity of Albizzia lebbeck, Hibiscus rosa sinesis and Butea monosperma in experimental animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamasaki H, Uefuji H, Sakihama Y. Bleaching of red anthocyanin induced by superoxide radical. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;332:183–6. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puckhaber LS, Stipanovic RD, Bost GA. Analyses for flavonoid aglycones in fresh and preserved Hibiscus flowers. In: Janick J, Whipkey A, editors. Trends in new crops and new uses. Alexandria, VA: ASHS Press; 2002. pp. 556–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butterweck V, Jurgenliemk G, Nahrstedt A, Winterhoff H. Flavonoids from Hypericum perforatum show antidepressant-like activity in the forced swimming test. Planta Med. 2000;66:3–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-11119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butterweck V, Nishibe S, Sasaki T, Uchida M. Antidepressant effects of Apocynum venetum leaves in forced swimming test. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:848–51. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almeida ER, Rafeal KR, Couto GB, Ishigami AB. Anxiolytic and anticonvulsant effects on mice of flavonoids, linalool, and a-tocopherol presents in the extract of leaves of Cissus sicyoides L. (Vitaceae) J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:274740. doi: 10.1155/2009/274740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadav AV, Kawale LA, Nade VS. Effect of Morus alba (mulberry) leaves on anxiety in mice. Indian J Pharmacol. 2008;40:32–6. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.40487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harborne JB. Flavonoids. In: Chapman, Hall, editors. Phytochemical methods: A guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. New Delhi: Springer Publication; 1998. pp. 54–84. London. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ukwueze NN, Nwadinigwe CA, Okoye CO, Okoye FB. Potentials of 3, 3, 4, 5, 7-pentahydroxyflavylium of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. (Malvaceae) flowers as ligand in the quantitative determination of Pb, Cd and Cr. International Journal of Physical Sciences. 2009;4:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans WC. Trease & Evans – Pharmacognosy. (241, 336, 368).Saunders WB. 2002:93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, Simon P. Tail suspension test: A new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1985;85:367–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00428203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioural despair in mice: A primary screening test for antidepressants. Arch Int Pharmacodyn. 1977;229:327–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhingra D, Kumar V. Evidences for the involvement of monoaminergic and GABAergic system in antidepressant –like activity of garlic extract in mice. Indian J Pharmacol. 2008;40:175–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.43165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner RA. Screening methods in pharmacology. Vol. 1. By London Academic Press, Inc; 1962. Organisation of screening; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmoudi M, Ebrahimzadeh MA, Ansaroudi F, Nabavi SF, Nabavi SM. Antidepressant and antioxidant activities of Artemisia absinthium L. at flowering stage. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:7170–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willner P. The validity of animal models of depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;83:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00427414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stahl SM. Psychopharmacology of antidepressants. London: Martin Dunitz Publisher; ISBN 1-85317-513-7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cubeddu LX. New alpha 1 -adrenergic receptor antagonists for treatment of hypertension: Role of vascular alpha receptors in the control of peripheral resistance. Am Heart J. 1998;16:133–62. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noldner M, Schotz K. Rutin is essential for the antidepressant-like activity of Hypericum perforatum extracts in the forced swimming test. Planta Med. 2002;68:577–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finar IL. Organic chemistry stereochemistry and the chemistry of natural products. London: Longmans; 1980. Anthocyanins; pp. 784–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harborne JB. Spectral methods of characterizing anthocyanins. Biochem J. 1958;70:22–8. doi: 10.1042/bj0700022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]