Abstract

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is damage to spinal cord, which is categorized according to the extent of functional loss, sensation loss and inability of the subjects to stand and walk. The patients use two transportation systems including orthosis and wheelchair. It was claimed that standing and walking bring some benefits such as decreasing bone osteoporosis, prevention of pressure sores, and improvement of the function of the digestive system for SCI patients. Nevertheless, the question of wether or not there is enough evidence to support the effect of walking with orthosis on the health status of the subjects with SCI remains unanswered. In order to answer this question a review of the relevant literature was carried out. The review of the literature showed that evidence reported in the literature regarding the effectiveness of orthoses for improving the health condition of SCI patients was controversial. Many investigators had only used the comments of the users of orthoses. The benefits mentioned in various research studies regarding the use of orthosis included decreasing bone osteoprosis, preventing joint deformity, improving bowl and bladder function, improving digestive system function, decreasing muscle spasm, improving independent living, and improving respiratory and cardiovascular systems function. The findings of the studies reviewed also showed that improving the independent living and physiological health of the subjects were the only two benefits, which were supported by strong evidence. The review of the literature suggests that most published studies are in fact surveys, which collected questionnaire-based information from the users of orthosis.

Key Words: Spinal cord injury, bone mineral density, orthosis, bone density

Introduction

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is a damage to the spinal cord that results in the loss of mobility and sensation below the level of injury. The disorder is characterized according to the amount of functional loss, sensational loss, and inability to stand and walk.1-3 The incidence of SCI varies amongst countries. For example there are 12.7 and 59 new cases per million in France and the United States of America, respectively.4,5 It may be the result of trauma, especially motor vehicle accident, penetrating injuries, or diseases. As a result of this type of disability, most individuals with SCI rely on a wheelchair for their mobility. They can transport themselves from one place to another using a manual wheelchair with a speed and energy expenditure similar to normal subjects.6,7

Although, the use wheelchair provides mobility to such patients, it is not without problems. The main problems are the restriction to mobility from architectural features in the landscape, and a number of health issues due to prolonged sitting. Decubitus ulcers, osteoporosis, joint deformities, especially hip joint adduction contracture, can result from prolonged wheelchair use.8 Individuals with SCI often undergo various rehabilitation programmes for walking and exercises. It has been suggested that by decreasing urinary tract infections, improving cardiovascular and digestive systems functions and psychological health walking is a good exercise for paraplegics in order to maintain good health.8

In contrast, most patients prefer not to use an orthosis, or use it occasionally. They have mentioned some problem associated with use of orthoses. The main problem with orthosis use is the high energy demands it places on the users during ambulation. In contrast to mobility speed with a wheelchair, the mobility speed of a SCI patient with an orthosis is significantly less than that of normal walking.9-13

Donning and doffing of the orthosis is another important problem associated with the use of an orthosis.14 The high amount of the force applied on the upper limb musculature is another issue, which affects the use of an orthosis. Depending on the style of walking, between 30% and 55% of body weight is applied on the crutch during walking.15-17 The high extent of the force, which is transmitted to the upper limb joints, increases the incidence of some diseases as well as shoulder pain.18,19 Fear to fall, especially during hand function performances, is another problem of using an orthosis.

Although standing with an orthosis may have some benefits for the patients, it has a number of problems. Therefore, the main question that remains is wether or not walking and standing with an orthosis can fulfil the afore-mentioned benefits. Unfortunately, the information mentioned in some textbooks regarding the benefits of using an orthosis for SCI individuals are based on the survey studies. So, the aim of the present review was to find some evidence regarding the effect of using orthoses on physiological improvement of subjects with SCI. Moreover, it was aimed to find the performance of paraplegic subjects during walking with orthoses and the problems associated with the use of orthoses.

Methods

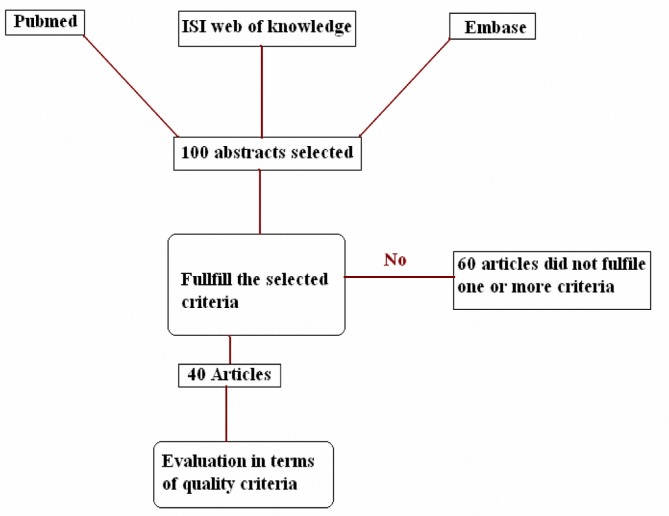

An electronic search was done via the Pubmed, Embase and ISI web of knowledge data bases from 1960 to 2010. The abstracts and title of each individual study was assessed by the author. The selection of papers for review was accomplished in two steps. In the first step, relevant articles were selected based on whether the title/abstract addressed the research questions of interest based on some key words such as, Spinal Cord injury, Physiological benefits, Walking, Standing and Orthosis. In the second step papers whose language of publication was English, addressing the adults and children with paraplegia and/or quadriplegia, and those in which subjects used orthoses or frame to improve some parameters such as, Bone Mineral Density (BMD), respiratory system function, cardiovascular system function, and joints range of motion were selected. The algorithm of search and selection of papers is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The algorithm of search and selection of papers to include in the review

Findings

From an initial list of 100 articles, 40 articles were fully retrieved and reviewed, based on key words and parameters included. The results of the research articles were fully reviewed and categorized based on the mentioned benefits. The results of the various research studies regarding the performance of the orthoses were categorized based on energy consumption, and gait and stability analysis. The results of reviewing the articles are shown in the following tables 1-13.

Table 1.

The findings of various studies regarding the effects of standing and walking on bone mineral density

| Reference | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|

| [20] | Eight SCI subjects with complete lesion at levels C7-L1participated in the study. The bone mineral density (BMD) was measured at proximal tibia, lumber spine and at tibia shaft 41 months after injury. | The BMD remained unchanged in lumber spine, but decreased to 50 % and 70% of normal value at proximal tibia and neckof femur, respectively. |

| [21] | Ten SCI subjects with lesions at levels C6-T4 participated in the study. The BMD was measured at proximal tibia, lumber spine. The subjects were asked to be upright and do cycling 30 minutes per day, three days per week and for 12 months. | The BMD remained unchanged in lumber spine, but increased by 10% in the proximal tibia. |

| [21] | Ten SCI subjects with lesions at levels C6-T4 participated in this study. The BMD was measured at proximal tibia, lumber spine. The subjects were asked to be upright and do cycling 30 minutes per day, one day per week and for six months. | The BMD remained unchanged in lumbar spine and proximal tibia. |

| [22] | Subjects with SCI (n=26) with complete lesion were recruited. The BMD at lumber spine, femoral neck and shaft, proximal tibia was measured 2-25years after injury. | The BMD of the femoral neck and shaft decreased by 25%. For proximal tibia it decreased by more than 50%. Using Knee ankle foot orthosis (KAFO) did not influence BMD. |

| [23] | Subjects with SCI (n=54) participated in the research study. No information regarding the level of lesion or age of the subjects was given. The subjects were asked to stand one hour per day and not less than five days per week for a period varied between 12 and 24 months. | Leg BMD reduced by 19.62% in the standing group and 24% in none standing group. |

| [24, 25] | Subjects with SCI (n=46) with complete and incomplete lesion were recruited for the study. The BMD of lumbar spine, proximal and distal parts of femur was measured between one and 26 years after injury. | The BMD was not significantly influenced by the levels of lesion and ambulatory status. Every effort should be expended to prevent turning an incomplete into complete lesion. The rehabilitation should be life long. |

| [8] | Subjects with SCI (n=133) with complete and incomplete lesion participated in the study. | |

| [26] | Six SCI individuals participated in this study. No information regarding the level of lesion was given. The BMD of long bones was measured 19 years after injury. The standing time was 144 hours over a mean of 135 days. | Standing did not modify the bone density in any site. |

| [27] | Subjects with SCI (n=53) were recruited in this research study. No information was given regarding the level of lesion). The BMD of femur was measured one year after walking with long leg brace and using wheelchair | The use of long leg brace had significant effects on BMD at the proximal femur. The results of this research showed that passive mechanical loading could have a beneficial effect on preservation of bone mass. |

| [28] | Eighty individuals with myelomeningocele lesion at T4-T5 were recruited in this research study. The BMD at distal radius and tibia was measured. | Although ambulatory status and neurological status (muscle stress) were both important factors in bone density, this study suggested that the latter was a more important. |

Table 13.

The findings of various studies regarding the physiological cost index (PCI) of paraplegic subjects during walking with various orthoses

| Reference | Type of orthosis | PCI (beats/metre) |

|---|---|---|

| [10] | HGO | 0.95-1.65 |

| [10] | Parawaker 89 | 0.8-1.26 |

| [50] | ARGO | 5.4 |

| [50] | NRGO | 5.8 |

| [55] | Walk about | 11.5 |

| [55] | MMLO | 11.5 |

| [44] | WBC | 1.9 |

| [44] | HGO | 3.6 |

HGO=hip guidance orthosis, ARGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis, NRGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis without cable, MMLO=Moorong medial linkage orthosis, WBC=weight bearing control orthosis

Table 6.

The findings of various studies regarding the stability of paraplegic subjects while undertaking various hand tasks

| Reference | Type of orthosis | COP sway in AP (mm) | COP sway in ML (mm) | Sway path in AP (m) | Sway path in ML (m) | Time for transverse motion (s) | Crutch peak force (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [36] | Linked KAFO | 4.78 | 4.94 | 0.91 | 0.34 | ---------- | ----------- |

| [36] | Unlinked KAFO | 5.35 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.76 | ----------- | ------------ |

| [34] | ARGO | --------- | --------- | -------- | ---------- | 11.12 | 179.75 |

| [34] | NRGO | ---------- | ----------- | -------- | --------- | 11.54 | 198 |

| Staking plates | |||||||

| [36] | Linked KAFO | 5.6 | 3.74 | 1.03 | 1.94 | ----------- | ----------- |

| [36] | Unlinked KAFO | 5.8 | 3.24 | 1.07 | 0.74 | ----------- | ----------- |

KAFO=knee ankle foot orthosis, ARGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis, NRGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis without cable, ML=mediolateral, AP=anteroposterior, COP=centre of pressure, N=Newton, s=second, m=meter, mm=millimetre

Table 8.

The findings of various studies regarding the gait parameters of the subjects in walking with various orthoses

| Reference | Number | Level of lesion | Orthosis |

Hip Ext

(degree) |

Hip Flex | Hip Abd | Hip Add |

Pelvis

(sajittal) |

Pelvis (frontal) |

Pelvis

( transverse) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | 1 | T5 | LSU RGO | 33 | 15 | 3 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 23 |

| [42] | 1 | T5 | ARGO | 35 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 17 | 17 | 26 |

| [42] | 1 | T5 | HGO | 21 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 33 |

| [43] | 4 | T8-T12 | WBC | 44.73 (flexion extension excursion) | ------ | ------ | ---------- | --------- | ------------- | |

WBC=weight bearing control orthosis, Abd=abduction, Add=adduction, Flex=flexion, Ext=extension

Table 9.

The findings of various studies regarding some gait parameters during walking with various orthoses

| Reference | Number | Level of lesion | Orthosis | Pattern of walking |

Velocity

(m/min) |

Stride length

(m) |

Cadence

(steps/min) |

Stance phase

percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | 1 | T7 | WBC | Reciprocal gait | 21.2 | 1.1 | 38.4 | ------------ |

| [44] | 1 | T7 | HGO | Reciprocal gait | 8 | 0.66 | 24.2 | ------------- |

| [45] | 1 | T12 | ARGO with locked knee | Reciprocal gait | 12 | 0.84 | 28.8 | --------------- |

| [45] | 1 | T12 | ARGO with controlled knee | Reciprocal gait | 10.8 | 0.79 | 26.8 | -------------- |

| [46] | 2 | T6 | Orthosis with flex knee | Reciprocal gait | 7.2-8.4 | 0.65-0.8 | --------- | -------------- |

| [46] | 2 | T6 | Orthosis with flex knee and ankle | Reciprocal gait | 7.8-8.4 | 0.58-0.82 | ---------- | --------------- |

WBC=weight bearing control orthosis, HGO=hip guidance orthosis, KAFO=knee ankle foot orthosis, ARGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis

Table 10.

The findings of various studies regarding the results of some gait parameters in walking with various orthoses

| Reference | Number | Level of lesion | Orthosis | Pattern of walking | Velocity | Stride length | Cadence | Stance phase percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | 10 | C5-T12 | Crutches | Swing through gait | 18-48 | 0.43-0.67 | 42-89.3 | 69/31-74/26 |

| [40] | 10 | C5-T12 | Walker | Swing through gait | 10-24 | 0.3 | 30 | 73/27-95/5 |

| [47] | 9 | No data | KAFO | Swing through gait | 41.7-59.9 | 1.23-1.5 | 67-79 | 64.6-70.7 |

| [47] | 9 | No data | KAFO | Swing to gait | 23.4 | 0.53 | 88 | 83.9 |

| [37] | 5 | L3-L4 | HKAFO | Swing through gait | 35.4 | 0.86 | 75.43 | 63 |

| [37] | 5 | L3-L4 | RGO | Reciprocal gait | 23.4 | 0.66 | 67.12 | 66 |

| [42] | 1 | T5 | RGO | Reciprocal gait | 18 | 1.02 | 35 | 67 |

| [42] | 1 | T5 | ARGO | Reciprocal gait | 18.6 | 0.99 | 37 | 67 |

| [42] | 1 | T5 | HGO | Reciprocal gait | 18 | 0.98 | 37 | 67 |

| [48] | 29 | T2-L5 | VRSO | Swing through gait | 26 | ------------ | ----------- | ------------- |

| [49] | 8 | C7-T12 | Scot Craig KAFO | Swing through gait | 8.8- 17.5 | ----------- | ---------- | -------------- |

| [49] | 8 | C7-T12 | KAFO with single Ankle | Swing through gait | 6.3-15.3 | ----------- | ---------- | -------------- |

| [50] | 5 | T4-T12 | ARGO | Reciprocal gait | 14.4 | 0.89 | 32 | ------------ |

| [50] | 5 | T4-T12 | NRGO | Reciprocal gait | 13.8 | 0.83 | 31.6 | ------------ |

| [51] | 21 | RGO | Reciprocal gait | 12.6 | 0.72 | 34.5 | 76.5 | |

| [51] | 21 | RGO with FES | Reciprocal gait | 12 | 0.72 | 33.61 | 77.22 | |

| [43] | 4 | T8-T12 | WBC | Reciprocal gait | 19.88 | -------------- | 44 | ------------ |

KAFO=knee ankle foot orthosis, HKAFO=hip knee ankle Foot orthosis, RGO=reciprocal gait orthosis, HGO=hip guidance orthosis, VRSO=Vannini Rizzoli stabilizing orthosis, FES=functional electrical stimulation, ARGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis, NRGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis without cable, WBC=weight bearing control orthosis

Discussion

According to the results of the research undertaken by Biering et al.56 BMD of long bone, such as femur and tibia decreased significantly after injury. It may be a result of decreasing the compression loads applied on the long bones, or may be related to the lack of muscles stress applied on the bones.20 Most of the research done regarding the effects of using orthosis on BMD have shown that walking and standing with orthoses do not influence the magnitude of osteoporosis as much as expected.22,27 The preservation of BMD in lumber spine is more than that in long bones.20 It may be due to the maintain of the loads on the spine while sitting in a wheelchair.

There is only one study, which specifically mentioned that walking with orthosis brought a lot of physiological benefits for the subjects without presenting any evidence.8 Unfortunately many textbooks in this field refer to that paper without considering the results of other research studies.57-59

The other important parameters regarding the influence of standing and walking on BMD is the duration of using an orthosis. It was shown that walking and standing with an orthosis must be life-long, and must be repeated several times a week to have any effects on bone osteoporosis (at least five session a week and one hour every cession). The use of mechanical orthoses and the neurological status (muscles stress), to remain ambulatory are two important parameters which influence BMD. However the findings of various research studies have shown that the effect of the latter is more important (table 1 and 2).28

Table 2.

The findings of various studies regarding the effects of standing and walking on skin integrity

| Reference | Method | Results |

| [29] | A 17-items self-report survey questionnaire was sent to 463 adult patients, and 152 adult subjects with SCI (n=152) returned the questionnaire and were included in the study. | They mentioned some benefits such as skin integrity and well–being. |

| [30] | The study was an investigation through a national survey of a sample of individuals with SCI. | There was a favourite response on the effects of standing devices on the number of bed sores in some individuals. |

| [31] | Thirty six spina bifida patients used wheelchair compared with another 36 patients walked with orthosis | The patients, who walked early, had fewer fractures and pressure sores, were more independent, and were more able to transfer |

It seems that the type of injury, wether or not complete, influences the BMD. The patients with incomplete lesion have more BMD than those with a complete one.24,25 Therefore, every effort should be made to prevent turning an incomplete SCI into a complete one (table 3). Last but not least important point regarding the effects of using orthosis on the BMD of SCI patients is that some of the research studies, which their outcome differs from SCI, have been carried out on patients with spina bifida and myelomeningocele patients.8,31

Table 3.

The findings of various studies regarding the effects of standing and walking on improving bowel and bladder function and urinary tract infection

| Reference | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|

| [8] | No real research was performed in this paper. It discussed the benefit of doing research only | The use of orthoses has a positive effects on bowel regularity, and decreased the number of urinary tract infections |

| [30] | This was an investigation through a national survey of a sample of individuals with SCI (paraplegia and quadriplegia) | There was a favourable response to the effects of standing devices on the number of urinary tract infections and on bowel regularity in some individuals They reported that they were able to empty their bladder more completely. |

| [32] | A group of paraplegic subjects used a particular ambulatory orthosis for upright weight bearing and walking. The amount of urine bacteria was counted before and after using orthosis | There was a reduction in urinary tract infections, but there was no corresponding reduction in the level of bacteria. |

The results of various studies regarding the effects of using orthosis on spasticity are shown in table 4. As the table shows, the majority of researches cited are survey-based. The investigators had sent questionnaires to individuals with SCI. Unfortunately, most of the subjects did not return the questionnaires. According to the findings of different investigations undertaken on SCI subjects, there was a favourable response to the use of orthosis on spasticity.26,33 There are a number of ways, which can be used to measure spasticity clinically and biomechanically such as using Ashworth scale, counting beats of clonus, Tardieu scale, muscle stretch reflexes, and functional tests.60

Table 4.

The findings of various studies regarding the effects of standing and walking on improving joint range of motion and decreasing muscle spasticity

| Reference | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|

| [26] | Six paraplegic men with a mean age of 49 years used orthosis for 19 years. They were been asked to walk 144 times per 135 days. | The results showed that there was no important difference between initial and final scores for clinical assessment and joint range of motion. |

| [33] | Twenty five SCI patients walking with orthosis participated in this research. | Maintained range of motion and prevention of joint deformity were the two most important outcomes mentioned by the researchers. |

It seems that standing and walking with an orthosis extends the hip and knee joints, and stretches the surrounding muscles. So, applying body weight through leg reduces muscle spasm more efficiency than stretching the muscles only in a supine position.8,57 However, there is no evidence to support this view.

It has been stated that in standing position, the pelvic tends to tilts more anteriorly than in sitting position. This increase lumber lordosis, and finally stabilizes the spine in an extended posture. In this posture, the force applied on the internal organs decreases, and as a result the performance of respiratory organs increases.8,57 Abdominal organs fall downward and forward during standing, because there is no an abdominal muscle to increase the stability of the abdominal walls anteriorly. At the end, the force applied on diaphragm decreases, and respiratory function improves.8 However, it was shown by Ogilive that the use of orthosis and ambulation did not affect the respiratory function of participants 24 months after continued use of orthoses (table 5).32

Table 5.

The findings of various studies regarding the stability of paraplegic subjects in a quiet standing position with various orthoses

| Reference | Number | Position of lesion |

Type of

orthosis |

COP path length (m/m) | COP sway ML | COP sway AP (mm) | Force applied on crutch (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | 9 | T4-T12 | ARGO | ------- | 41.72 | 35.22 | 43.26 |

| [34] | 9 | T4-T12 | NRGO | ------- | 34.53 | 37.94 | 59.3 |

| [35] | 2 | T4-T12 | KAFO | 0.51-0.62 | -------- | -------- | --------- |

| [35] | 2 | T4-T12 | MLO | 0.123-0.2 | -------- | --------- | ---------- |

| [35] | 2 | T4-T12 | RGO | 0.116-0.16 | --------- | ---------- | ------------ |

| [36] | 9 | T4-T12 | Linked KAFO | 0.74 | 1.11 | 1.75 | ------------- |

| [36] | 9 | T4-T12 | Unlinked KAFO | 0.659 | 1.087 | 2.07 | ------------ |

ARGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis, NRGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis without cable, KAFO=knee ankle foot orthosis, MLO=medial linkage orthosis, ML=mediolateral, AP=anteroposterior, COP=centre of pressure, N=Newton, m=meter, mm=millimeter

Improvement of the function of the cardiovascular system is a further benefits mentioned in the literature for ambulation with orthosis.8 However, there is no evidence in literature to support this view. Douglas et al mentioned that walking with orthosis influenced the performance of the cardiovascular system in 133 patients with SCI. There was no clear description of the method, which was used to monitor the function of cardiovascular system in the subjects participating in the study. It seems that the authors only presented the comments of the orthotic users.8

The decrease of urinary tract infections and improvement in the function of bowel and bladder are the other benefits mentioned to be achieved from orthosis ambulation. There are only two research studies based on national survey of samples of individuals with SCI possessing symptoms of paraplegia or quadriplegia (table 3).30,32 The subject participated in these studies mentioned that walking with orthosis decreased the number of urinary tract infections, and regulated the functions of bowel and bladder. They reported that they were able to empty their bladder more completely.32 Unfortunately, there is no clinical research, which has evaluated the effect of using orthosis on improving the performance of bowel and bladder function.

Another benefit, which was mentioned by Douglas et al regarding the benefits of using orthosis, is the prevention of joint deformity and improvement of joint range of motion. They claimed that during standing the body weight is applied vertically downward and symmetrically upon both feet. In standing position the gravitational positioning of flexed joints decreased, and as a result the risk of deformity of lower limb joint decreased as well.8 Moreover, Middleton et al mention that maintaining range of motion and preventing of joint deformity were the two most important outcomes presented by the participants. However, they did not show any evidence to support their findings (table 4).33

According to the results of various research studies, the main problems associated with the use of orthosis is the high energy demand it places on the users during ambulation (tables 11, 12, 13).6,7,49,52-54,61 Moreover, the walking speed in a SCI individuals with an orthoses is significantly less than that of healthy individuals and also in contrast to mobility with a wheelchair (tables 11, 12, 13). Although, the type of orthosis and style of walking influence the magnitude of energy consumption, there is a huge difference between the energy consumptions between walking with and without orthosis.62 As is shown in tables 11, 12, 13 there is a big difference between the performances of the subjects in walking with various types of orthoses. Some parameters such as the type of orthosis, the position of lesion in vertebral column, age of subjects, and the style of walking influence the performance of the subjects.6,7,49,52

Table 11.

The findings of various studies regarding some results of energy consumption tests

| Research |

Number of

subjects |

Level of

lesion |

Type of

orthosis |

Style of walking | Walking velocity |

Energy cost

(J/kg/m) |

Energy

consumption (J/kg/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | 25 | T1-T12 | Double KAFO | Swing through gait | 26±16 | 15.278 ±10.25 |

288.83 ±100.496 |

| [52] | 8 | T4-T12 | Resting | Swing through gait | ------ | ----------- | 76.5 |

| [52] | 8 | T4-T12 | Craig-Scott orthosis | Swing through gait | -------- | -------------- | 234.12 |

| [53] | 10 | T4-T9 | HGO orthosis |

Reciprocal gait | 12.84 | 16 | 186 |

| [54] | 26 | T12-L3,4 | RGO | Reciprocal gait | 16.2 | 16.92 ±7.1 |

239.1 ±38.66 |

| [54] | 26 | T12-L3,4 | HKAFO | Reciprocal gait | 40.8 | 11.28 ±2.51 |

441 ±64.372 |

| [6] | 3 | T11-L2 | KAFO | Swing through gait | 32.4 | 20.69 | 446.84 |

| [6] | 11 | T11-L2 | Wheel chair |

------------ | 84.9 | 4.28 | 430.54 |

| [7] | 100 | -------- | Normal subject wheelchair |

------------- | --------- | 3.135 ±0.418 |

248.71 ±48.07 |

| [7] | 10 | T1-T9 | Orthosis SCI |

Swing through gait | --------- | 15.46 ±10.45 |

303 ±89.87 |

| [7] | 55 | T1-T9 | Wheelchair SCI |

------------- | ------- | 3.34 ±0.627 |

240.35 ±64.79 |

KAFO=knee ankle foot orthosis, HKAFO=hip knee ankle Foot orthosis, HGO=hip guidance orthosis, RGO=reciprocal gait orthosis, SCI=spinal cord injury

Table 12.

The findings of various studies regarding the energy consumption of paraplegic subjects during walking with various orthoses

| Research | Number of subjects |

Level of

lesion |

Type of orthosis |

Style of

walking |

Walking velocity |

Energy cost

(J/kg/m) |

Energy

consumption (J/kg/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] | 8 | C7-T12 | Scot Craig KAFO with crutch | Swing through gait | 17.5 | 63.95 | ------------- |

| [49] | 8 | C7-T12 | KAFO with Single stop ankle joint with crutch | Swing through gait | 15.3 | 73.15 | ----------- |

| [49] | 8 | C7-T12 | Scot Craig KAFO with walker | Swing through gait | 8.8 | 26.38 | ----------- |

| [49] | 8 | C7-T12 | KAFO with Single stop ankle joint with walker | Swing through gait | 6.3 | 36.78 | ------------- |

| [43] | 4 | T8-T12 | WBC | Reciprocal gait | 19 | 119.5 | ----------- |

| [50] | 6 | T4-T12 | ARGO | Reciprocal gait | ------------ | ---------- | 355.58 |

| [50] | 6 | T4-T12 | NRGO | Reciprocal gait | ------------ | ------------- | 376.1 |

KAFO=knee ankle foot orthosis, WBC=weight bearing control orthosis, ARGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis, NRGO=advance reciprocal gait orthosis without cable

The high magnitude of the force applied on upper limb musculature is another issue that affects the use of orthosis. Depend on the style of walking, between 30% and 55% of body weight is applied on the crutch during walking (table 7).15,40,63,64 The high magnitude of the force, which is transmitted to upper limb joints, increases the incidence of some diseases and the pain of shoulder.

Table 7.

The findings of various studies regarding the force applied on the foot and crutch during walking with various orthoses

| Reference |

Number

of subjects |

Position

of lesion |

Foot force (N/BW) |

Crutch

force (N/BW) |

Foot

vertical impulse |

Crutch vertical

impulse |

Type of

walking |

Type of orthosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | 5 | T1-T10 | 0.784-1.042 | 0.288-0.296 | 0.712-0.794 | 0.206-0.288 | Rec | HGO |

| [37] | 5 | L3-L4 | -------- | 0.447-0.451 | ---------- | --------- | Rec | RGO |

| [37] | 5 | L3-L4 | -------- | 0.556-0.572 | ---------- | --------- | Swi | HKAFO |

| [15] | 1 | L2 | 0.90-1.10 | 0.35 | -------- | -------- | Rec | HGO |

| [38] | 9 | T4-T9 | 0.29- 0.98 | 0.40 | --------- | -------- | Rec | HGO |

| [39] | 1 | T7 | 0.83 | 0.33 | --------- | -------- | Rec | RGO |

| [40] | 10 | C5-T12 | ----------- | 0.15-0.50 | -------- | ------ | Swi | No orthosis with crutch |

| [40] | 10 | C5-T12 | ----------- | 0.39-0.74 | -------- | ------ | Swi | No orthosis with walker |

| [11] | 5 | T4-T12 | ------------ | 0.39- 0.43 |

---------- | 0.59 | Rec | ARGO (1) |

| [11] | 5 | T4-T12 | ------------ | 0.36- 0.40 |

----------- | 0.57 | Rec | ARGO (2) |

| [11] | 5 | T4-T12 | ------------- | 0.36- 0.41 |

--------- | 0.57 | Rec | ARGO (3) |

| [11] | 5 | T4-T12 | ------------ | 0.33- 0.40 |

----------- | 0.59 | Rec | ARGO (4) |

| [41] | 2 | T4-T8 | ----------- | 0.225- 0.36 |

------------ | 306-522.2 N.s | Rec | ARGO |

| [41] | 2 | T4-T8 | ------------ | 0.22- 0.385 |

------------- | 310.2-529 N.s | Rec | ARGO hybrid |

Rec=reciprocal gait mechanism, Swi=swing through gait mechanism, HGO: hip guidance orthosis, RGO=reciprocal gait orthosis, HKAFO=hip knee ankle Foot orthosis, ARGO=advanced reciprocal gait orthosis, ARGO (1)=ARGO orthosis aligned in 6 degrees of abduction, ARGO (2)=ARGO orthosis aligned in 0 degrees of abduction, ARGO (3)=ARGO orthosis aligned in 3 degrees of abduction, ARGO (4)=ARGO orthosis aligned in 6 degrees of adduction, N/BW=newtone/body weigh

Donning and doffing of orthoses is another important problem associated with the use of an orthosis. Herman and Biering found that only three out of 45 patients continued using their orthosis after 10 years. The reason that they mentioned for withdrawing from the use of orthoses was the considerable time that they needed to spend on putting on and taking off the orthosis.14

Although the results of the afore-mentioned investigations can not support the effects of walking and standing with orthosis on physiological health of the SCI individuals, it is difficult to ignore the positive influences of orthosis. It is recommended to undertake further studies with a sufficient number of participants, and follow the subjects for a long time. Moreover, the performance of the subjects in using the orthoses as well as the impact of the orthoses on the health status of the subjects must be measured according to the standard methods discussed in this article.

Conclusion

A number of publication have emphasized that walking with orthosis is associated some benefits for individuals with SCI, such as improving BMD, improving the functions of cardiovascular, digestive and respiratory systems, decreasing muscles spasm, and joint contractions. However, the findings of various studies have shown that the effects of using orthosis on physiological health are not as much as they are supposed to be. There is no any strong evidence that the use of orthosis can decrease bone osteoporosis, muscle spasm, and improve general health. Moreover, most of the studies in this field are survey-based. It can be concluded that in order to have any influences on the health status of SCI patients, the use the orthosis for standing and walking must be long-life. Moreover, orthoses must be worn four to five sessions of at least one hour every week.

A variety of orthoses have been designed to enable SCI individuals to stand and walk. They use different mechanisms to stabilize the paralyzed joints, and to move the limbs forward during walking. Different sources of power such as pneumatic pumps, hydraulic pumps, muscular force resulting from electrical stimulation, and electrical motors have been attempted for walking. However, the results of different studies have shown that the performance of SCI individuals during walking with the mechanical orthosis is very low, and the patients experience a lot of problems in using the orthoses. Many of the SCI individuals discontinue from using their orthoses after they obtain it. The patients reported some problems such as high demand for the energy expenditure and mechanical work during walking with orthoses, poor cosmesis of the orthoses, especially the hip guidance orthosis, needing considerable time and sometimes assistance for donning and doffing, and problems related to the fear of falling.

It is recommended that to have any influences on physiological health of the SCI subjects, orthosis must be used for a long time. However, the patients have lots of problems with donning and doffing the orthosis. Therefore, the design of the orthosis must allow easy donning and doffing of the orthosis regularly. It is recommended to design a new orthosis with attachable components, which allow the subjects to wear it independently. The use of some sources of external power in orthoses may improve the performance of the subjects during walking.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Zampa A, Zacquini S, Rosin C, et al. Relationship between neurological level and functional recovery in spinal cord injury patients after rehabilitation. Europa Medicophysica. 2003;39:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stolov WC, Clowers MR. Handbook of severe disability: a text for rehabilitation counselors, other vocational practitioners, and allied health professionals. Washington: U.S. Dept. of Education Rehabilitation Services Administration; 1981. pp. 322–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capaul M, Zollinger H, Satz N, et al. Analyses of 94 consecutive spinal cord injury patients using ASIA definition and modified Frankel score classification. Paraplegia. 1994;32:583–7. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surkin J, Gilbert BJ, et al. Spinal cord injury in Mississippi. Findings and evaluation, 1992-1994. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:716–21. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton NG. Injuries of the spinal cord the management of paraplegia and tetraplegia. London: Butterworths; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerny D, Waters R, Hislop H, Perry J. Walking and wheelchair energetics in persons with paraplegia. Phys Ther. 1980;60:1133–9. doi: 10.1093/ptj/60.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters RI, Lunsford BR. Energy cost of paraplegic locomotion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1245–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas R, Larson PF, McCall RE. The LSU Reciprocal-Gait Orthosis. Orthopedics. 1983;6:834–8. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19830701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulkar B, Yavuzer G, Guner R, Ergin S. Energy expenditure of the paraplegic gait: comparison between different walking aids and normal subjects. Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26:213–7. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stallard J, Major RE. The influence of orthosis stiffness on paraplegic ambulation and its implications for functional electrical stimulation (FES) walking systems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1995;19:108–14. doi: 10.3109/03093649509080352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ijzerman MJ, Baardman G, Holweg GGJ, et al. The influence of frontal alignment in the Advanced Reciprocating Gait Orthosis on energy cost and crutch force requirements during paraplegic gait. Basic Appl Myol. 1997;7:123–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirokawa S, Solomonow M, Baratta R, D'Ambrosia R. Energy expenditure and fatiguability in paraplegic ambulation using reciprocating gait orthosis and electric stimulation. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18:115–22. doi: 10.3109/09638289609166028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters RL, Hislop HJ, Perry J, Antonelli D. Energetics: application to the study and management of locomotor disabilities. Energy cost of normal and pathologic gait. Orthop Clin North Am. 1978;9:351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawran S, Biering-Sørensen F. The use of long leg calipers for paraplegic patients: a follow-up study of patients discharged 1973-82. Spinal Cord. 1996;34:666–8. doi: 10.1038/sc.1996.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Major RE, Stallard J, Rose GK. The dynamics of walking using the hip guidance orthosis (hgo) with crutches. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1981;5:19–22. doi: 10.3109/03093648109146224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose GK. The principles and practice of hip guidance articulations. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1979;3:37–43. doi: 10.3109/03093647909164699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrarin M, Pedotti A, Boccardi S. Biomechanical assessment of paraplegic locomotion with hip guidance orthosis (HGO) Clin Rehabil. 1993;7:303–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subbarao JV, Klopfstein J, Turpin R. Prevalence and impact of wrist and shoulder pain in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 1994;18:9–13. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1995.11719374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalyan M, Cardenas DD, Gerard B. Upper extremity pain after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:191–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biering-Sørensen F, Bohr HH, Schaadt OP. Longitudinal study of bone mineral content in the lumbar spine, the forearm and the lower extremities after spinal cord injury. Eur J Clin Invest. 1990;20:330–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1990.tb01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohr T, Podenphant J, Biering-Sorensen F, et al. Increased bone mineral density after prolonged electrically induced cycle training of paralyzed limbs in spinal cord injured man. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997;61:22–5. doi: 10.1007/s002239900286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biering-Sørensen F, Bohr H, Schaadt O. Bone mineral content of the lumbar spine and lower extremities years after spinal cord lesion. Paraplegia. 1988;26:293–301. doi: 10.1038/sc.1988.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alekna V, Tamulaitiene M, Sinevicius T, Juocevicius A. Effect of weight-bearing activities on bone mineral density in spinal cord injured patients during the period of the first two years. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:727–32. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabo D, Blaich S, Wenz W, et al. Osteoporosis in patients with paralysis after spinal cord injury. A cross sectional study in 46 male patients with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:230–5. doi: 10.1007/s004020000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabo D, Blaich S, Wenz W, et al. Osteoporosis in patients with paralysis after spinal cord injury. A cross sectional study in 46 male patients with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:75–8. doi: 10.1007/s004020000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunkel CF, Scremin AM, Eisenberg B, et al. Effect of "standing" on spasticity, contracture, and osteoporosis in paralyzed males. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goemaere S, Kaufman JM. Bone mineral status in paraplegic patients who do or do not perform standing. Osteoporosis Int. 1994;4:138–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01623058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenstein BD, Greene WB, Herrington RT, Blum AS. Bone density in myelomeningocele: the effects of ambulatory status and other factors. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1987;29:486–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1987.tb02508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eng JJ, Levins SM, Townson AF, et al. Use of prolonged standing for individuals with spinal cord injuries. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1392–9. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.8.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn RB, Walter JS, Lucero Y, et al. Follow-up assessment of standing mobility device users. Assist Technol. 1998;10:84–93. doi: 10.1080/10400435.1998.10131966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazur JM, Shurtleff D, Menelaus M, Colliver J. Orthopaedic management of high-level spina bifida. Early walking compared with early use of a wheelchair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogilvie C, Bowker P, Rowley DI. The physiological benefits of paraplegic orthotically aided walking. Paraplegia. 1993;31:111–5. doi: 10.1038/sc.1993.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middleton JW, Yeo JD, Blanch L, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new orthosis, the 'walkabout', for restoration of functional standing and short distance mobility in spinal paralysed individuals. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:574–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baardman G, Ijzerman MJ, Hermens HJ, et al. The influence of the reciprocal hip joint link in the Advanced Reciprocating Gait Orthosis on standing performance in paraplegia. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1997;21:210–21. doi: 10.3109/03093649709164559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaoru A. Comparison of Static Balance, Walking Velocity, and Energy Consumption with Knee-Ankle-Foot Orthosis, Walkabout Orthosis, and Reciprocating Gait Orthosis in Thoracic-Level Paraplegic Patients. JPO. 2006;18:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Middleton JW, Sinclair PJ, Smith RM, Davis GM. Postural control during stance in paraplegia: effects of medially linked versus unlinked knee-ankle-foot orthoses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1558–65. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slavens BA, Frantz J, Sturm PF, Harris GF. Upper extremity dynamics during Lofstrand crutch-assisted gait in children with myelomeningocele. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:S165–71. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2007.11754596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nene AV, Major RE. Dynamics of reciprocal gait of adult paraplegics using the Para Walker (Hip Guidance Orthosis) Prosthet Orthot Int. 1987;11:124–7. doi: 10.3109/03093648709078194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tashman S, Zajac FE, Perkash I. Modeling and simulation of paraplegic ambulation in a reciprocating gait orthosis. J Biomech Eng. 1995;117:300–8. doi: 10.1115/1.2794185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melis EH, Torres-Moreno R, Barbeau H, Lemaire ED. Analysis of assisted-gait characteristics in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:430–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baardman G, IJzerman MJ, Hermens HJ, et al. Knee flexion during the swing phase of orthotic gait: influence on kinematics, kinetics and energy consumption in two paraplegic cases. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation. 2002;8:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jefferson RJ, Whittle MW. Performance of three walking orthoses for the paralysed: a case study using gait analysis. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1990;14:103–10. doi: 10.3109/03093649009080335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawashima N, Sone Y, Nakazawa K, et al. Energy expenditure during walking with weight-bearing control (WBC) orthosis in thoracic level of paraplegic patients. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:506–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yano H, Kaneko S, Nakazawa K, et al. A new concept of dynamic orthosis for paraplegia: the weight bearing control (WBC) orthosis. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1997;21:222–8. doi: 10.3109/03093649709164560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baardman G, IJzerman MJ, Hermens HJ, et al. Augmentation of the knee flexion during the swing phase of orthotic gait in paraplegia by means of functional electrical stimulation. Saudi J Disabil Rehabil. 2002;8:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greene PJ, Granat MH. A knee and ankle flexing hybrid orthosis for paraplegic ambulation. Med Eng Phys. 2003;25:539–45. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(03)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noreau L, Richards CL, Comeau F, Tardif D. Biomechanical analysis of swing-through gait in paraplegic and non-disabled individuals. J Biomech. 1995;28:689–700. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00118-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kent HO. Vannini-Rizzoli stabilizing orthosis (boot): preliminary report on a new ambulatory aid for spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:302–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merkel KD, Miller NE, Westbrook PR, Merritt JL. Energy expenditure of paraplegic patients standing and walking with two knee-ankle-foot orthoses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ijzerman MJ, Baardman G, Hermens HJ, et al. The influence of the reciprocal cable linkage in the advanced reciprocating gait orthosis on paraplegic gait performance. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1997;21:52–61. doi: 10.3109/03093649709164530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thoumie P, Beillot J, et al. Restoration of functional gait in paraplegic patients with the RGO-II hybrid orthosis. A multicenter controlled study. II: Physiological evaluation. Paraplegia. 1995;33:654–9. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang CT, Kuhlemeier KV, Moore NB, Fine PR. Energy cost of ambulation in paraplegic patients using Craig-Scott braces. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;60:595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nene AV, Patrick JH. Energy cost of paraplegic locomotion with the ORLAU ParaWalker. Paraplegia. 1989;27:5–18. doi: 10.1038/sc.1989.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cuddeford TJ, Freeling RP, Thomas SS, et al. Energy consumption in children with myelomeningocele: a comparison between reciprocating gait orthosis and hip-knee-ankle-foot orthosis ambulators. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:239–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Middleton JW, Fisher W, Davis GM, Smith RM. A medial linkage orthosis to assist ambulation after spinal cord injury. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1998;22:258–64. doi: 10.3109/03093649809164493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biering-SØRensen F, Bohr HH, Schaadt OP. Longitudinal study of bone mineral content in the lumbar spine, the forearm and the lower extremities after spinal cord injury. Eur J Clin Invest. 1990;20:330–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1990.tb01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, authors. Atlas of orthotics. 2nd. ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1985. pp. 199–237. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Redford JB. Orthotics etcetera. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rose GK. Orthotics: principles and practice. London: William Heinemann Medical; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winter DA. The biomechanics and motor control of human gait: normal, elderly and pathological. 2nd ed. Waterloo, Ont: Waterloo Biomechanics; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Butler P, Engelbrecht M, Major RE, et al. Physiological cost index of walking for normal children and its use as an indicator of physical handicap. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1984;26:607–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1984.tb04499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karimi MT, Spence W, Sandy A, Solomonidis S. How can the performance of the paraplegic patients be improved? Orthopaedic Technique. 2010;4:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Requejo PS, Wahl DP, Bontrager EL, et al. Upper extremity kinetics during Lofstrand crutch-assisted gait. Med Eng Phys. 2005;27:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crosbie WJ, Nicol AC. Biomechanical comparison of two paraplegic gait patterns. Clinical Biomechanics. 1990;5:97–107. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(90)90044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]