Abstract

Both urine and serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) reflect active chronic kidney disease and predict acute kidney injury (AKI). However, direct comparison of these markers in acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) has not been performed. We prospectively evaluated 93 patients admitted with ADHF and treated with intravenous furosemide, and measured both systemic (serum) and urine NGAL levels and their corresponding markers of estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), natriuresis (urine sodium) and diuretic response (net output, urine sodium to furosemide ratio). In our study cohort, median urine and serum NGAL levels were 34 [interquartile range 24–86] ng/mL and 252 [interquartile range 175–350] ng/mL, respectively. Urine and serum NGAL were modestly correlated (r=0.37, p<0.001). Higher urine (but not systemic) NGAL correlated with markers of impaired natriuresis and reduced diuresis (p<0.005 for all). In contrast, higher serum NGAL demonstrated a stronger relationship with reduced glomerular filtration function (p<0.0001). Both markers predicted AKI (urine NGAL: odds ratio 1.7, p=0.035; serum NGAL: odds ratio 1.9, p=0.009). In conclusion, in patients with ADHF, urine NGAL levels reflect renal distal tubular injury with impaired natriuresis and diuresis, while systemic NGAL levels demonstrate a stronger association with glomerular filtration function. Both systemic and urine NGAL predict worsening renal function.

Keywords: Cardio-renal, Heart failure, Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, Natriuresis, Diuresis

The inflammatory and oxidative stress responses accompanying renal injury have long been investigated as determinants that drive renal sodium retention independent of glomerular filtration rate (GFR)1,2. Tubulo-interstitial inflammation and oxidative stress enhance local angiotensin II generation, induce proximal tubule sodium reabsorption, compromise dopamine D1 receptor and nitric oxide mediated sodium excretion, and upregulate distal tubule sodium reabsorption in both the thick ascending limb and collecting ducts1–9. In acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), where worsening renal function limits effective diuresis to relieve volume overload, such mechanisms may contribute to impaired natriuresis and diuretic resistance10–12. No study has assessed markers of renal tubular inflammatory and oxidative stress such as NGAL with clinical measures of natriuresis and diuresis in the heart failure (HF) setting. In a cohort of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) and treated with intravenous diuretics, we examined the relation of systemic and urine NGAL, as markers of renal inflammatory and oxidative stress, with clinical measures of renal function, including GFR, natriuresis and diuresis, and clinical outcomes.

METHODS

This is a single-center, prospective study cohort of 93 patients admitted with ADHF. This study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board and all subjects gave informed consent. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥18 years, admission diagnosis of ADHF receiving intravenous furosemide therapy for fluid retention. Exclusion criteria included previous abdominal or thoracic surgery within the last 3 months, anticipated discharge from the hospital within 24 hours, urinary tract infection or bacteremia, renal replacement therapy or anuria, and inability to provide informed consent or comply with the study protocol. Net fluid output and weight loss were recorded for up to 5 days after baseline NGAL measurements or until discharge.

Simultaneous systemic (serum) and urine samples were collected at baseline after initiation of diuretic therapy, processed and immediately frozen in aliquots at −80°C until analyzed. Net fluid output and weight loss were then followed for up to 5 days after baseline NGAL measurements or until discharge. All laboratory analyses were performed with investigators blinded to cardio-renal indices and clinical outcomes data. Serum and urine NGAL levels were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Cat. No. KIT 036, BioPorto Diagnostics, Gentofte Denmark). The minimum detection limit of the assay was 4 pg/mL. Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 1.1 and 3.2%, respectively, at 65 ng/mL.

Urine sodium (uNa) was measured by ion selective electrode and urine creatinine (uCr) was measured by Roche enzymatic assay within the Cleveland Clinic Reference Laboratory. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation for uNa were 0.3 and 0.6%, respectively. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation for uCr were 0.9 and 2.1% respectively. Urine furosemide (uFurosemide) was assessed by NMS Labs utilizing high performance liquid chromatography. The minimum detection limit of the assay was 1.0 μg/mL, and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 9.5 and 7.3%. In this study, the ratio of uNa to uFurosemide represents the estimated natriuretic effect from diuretic therapy. Complete blood counts were collected at the Cleveland Clinic Reference Laboratory utilizing a Sysmex XE-2100 automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex America, Inc., Mundelein IL) as a part of standard of care. Baseline complete blood counts were collected on the same day as baseline NGAL measurements. If baseline complete blood counts were not available, complete blood counts were obtained from the closest date within 90 days of baseline NGAL measurements. Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were followed for up to 5 days after baseline NGAL measurements or until discharge. Estimated GFR was calculated by the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation13. AKI was defined as serum creatinine rise ≥0.3 mg/dl, chosen as a simplified version of the RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease) and AKIN (Acute Kidney Injury Network) criteria and commonly used in studies of acute cardio-renal syndrome14.

Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed, and as median and interquartile range [IQR] if non-normally distributed. Systemic and urine NGAL were non-normally distributed. Normality was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Spearman's rank correlation method was used as a nonparametric measure of association for correlations between systemic and urine NGAL levels and cardio-renal indices, including natriuretic and diuretic markers, GFR markers, indices of anemia, and echocardiographic indices. The Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare differences in systemic or urine NGAL across clinical categories, including gender, race, ischemic etiology, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, medication use, and presence of anemia. Differences in clinical variables, including natriuretic and diuretic markers, across median systemic and urine NGAL levels were assessed using either the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed variables or the Student's t-test for normally distributed variables. Differences in proportions were assessed using contingency table analysis. Odds ratios for the development of AKI within 5 days of baseline were calculated using logistic regression analysis and evaluated according to the likelihood ratio test. Predictor variables in our logistic regression analyses included standardized natural-logarithm transformed serum NGAL, standardized natural-logarithm transformed urine NGAL, serum NGAL ≥250 ng/mL, urine NGAL ≥64 ng/mL, standardized estimated GFR, and standardized serum creatinine. Serum NGAL =250 ng/mL and urine NGAL =64 ng/mL were the optimal cut-points maximizing sensitivity and specificity for the prediction of AKI in Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. All p-values reported are from two-sided tests and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

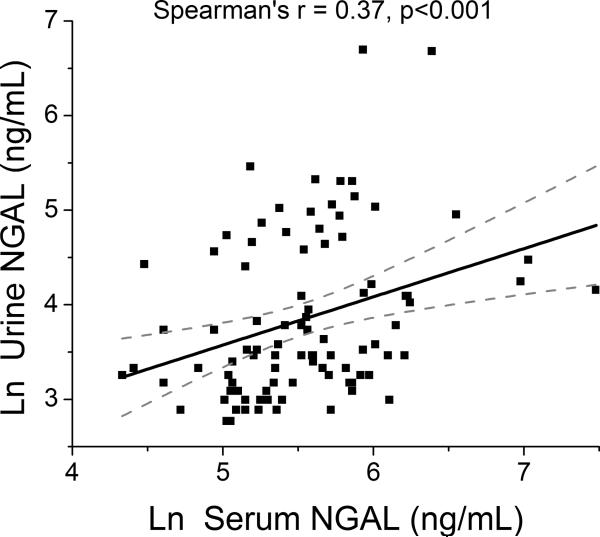

Table 1 illustrates the baseline characteristics of our study cohort stratified by GFR. Mean and median serum NGAL levels were 300 ± 230 ng/mL and 252 [IQR 175–350] ng/mL, respectively, while mean and median urine NGAL levels were 75 ± 120 ng/mL and 34 [IQR 24–86] ng/mL, respectively. Interestingly, serum and urine NGAL levels were only modestly correlated (r=0.37, p<0.001; Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Subject Characteristics Stratified by Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

| Variable | Overall Cohort | GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 | ≥60 | |||

| Age (years) | 64 ± 14 | 68 ± 14 | 58 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Men | 62 (67%)> | 31 (57%) | 31 (79%) | 0.023 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 33 ± 9 | 33 ± 8 | 33 ± 10 | 0.588 |

| Black | 28 (30%) | 15 (28%) | 13 (33%) | 0.565 |

| White | 63 (68%) | 37 (69%) | 26 (67%) | 0.851 |

| Ischemic HF etiology | 34 (40%) | 20 (41%) | 14 (38%) | 0.780 |

| Hypertension | 61 (66%) | 40 (74%) | 21 (54%) | 0.043 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (43%) | 26 (48%) | 14 (36%) | 0.237 |

| Anemia | 54 (58%) | 35 (65%) | 19 (49%) | 0.121 |

| Echocardiographic indices: | ||||

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 177 ± 60 | 171 ± 58 | 185 ± 63 | 0.327 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index (mL/m2) | 90 ± 47 | 85 ± 49 | 96 ± 43 | 0.118 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 34 ± 17 | 37 ± 17 | 29 ± 16 | 0.037 |

| Diastolic stage III | 60 (72%) | 32 (67%) | 28 (80%) | 0.175 |

| Medications: | ||||

| ACE Inhibitors and/or ARBs | 40 (46%) | 20 (39%) | 20 (56%) | 0.132 |

| Beta-blockers | 57 (66%) | 33 (65%) | 24 (67%) | 0.850 |

| Spironolactone | 26 (30%) | 16 (31%) | 10 (28%) | 0.718 |

| Loop diuretics | 72 (83%) | 43 (84%) | 29 (81%) | 0.649 |

| Digoxin | 20 (23%) | 10 (20%) | 10 (28%) | 0.375 |

| Laboratory data: | ||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 39 ± 22 | 51 ± 22 | 22 ± 8 | <0.0001 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 897 [458 – 1,949] | 901 [467 – 1899] | 805 [427 – 2004] | 0.667 |

| Intravenous furosemide dose (mg/day) | 225 ± 155 | 255 ± 158 | 182 ± 142 | 0.019 |

| Systemic NGAL (ng/mL) | 252 [175 – 350] | 306 [252 – 408] | 172 [150 – 210] | <0.0001 |

| Urine NGAL (ng/mL) | 34 [24 – 86] | 44 [28 – 114] | 28 [22 – 52] | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LV, left ventricular; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <12 g/dL if male and <11 g/dL if female.

Figure 1.

Relationship between Systemic (Serum) and Urine NGAL in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Abbreviations: NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Higher systemic (but not urine) NGAL levels were associated with advanced age (r=0.21, p=0.044). Systemic and urine NGAL levels were not correlated with systemic BNP levels, and did not differ according to gender, race, ischemic etiology, history of hypertension, or diabetes mellitus (p>0.10 for all), but patients with above-median urine NGAL levels did have a higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Systemic NGAL levels were lower in patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) (225 [166 – 292] versus 302 [185 – 401] ng/mL, p=0.013), but systemic or urine NGAL did not differ according to other medication use (p>0.33 for all).

Patients with above-median systemic NGAL levels demonstrated a higher prevalence of diastolic stage III and a lower left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, while both above-median systemic and urine NGAL were associated with higher left ventricular ejection fraction (Table 1). Systemic and urine NGAL levels both correlated with indices of anemia, including red blood cell (systemic NGAL: r= −0.31, p=0.003; urine NGAL: r= −0.26, p=0.012), hemoglobin (systemic NGAL: r= −0.35, p<0.001; urine NGAL: r= −0.28, p=0.007), hematocrit (systemic NGAL: r= −0.37, p<0.001; urine NGAL: r= −0.27, p=0.008), and red cell distribution width (systemic NGAL: r= 0.25, p=0.018). With anemia defined as hemoglobin <12 g/dL if male and <11 g/dL if female, the prevalence of anemia in our cohort was 54 (58%). Higher systemic NGAL levels were associated with the presence of anemia (OR: 1.87 [1.17 – 3.20], p=0.008), but higher urine NGAL was not (p=0.11).

High systemic NGAL levels demonstrated relatively strong associations with markers of poor glomerular filtration function (including GFR, serum creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen, Table 2). In comparison, urine NGAL was modestly associated with GFR and serum creatinine, and was not associated with blood urea nitrogen (Table 2). In addition, serum NGAL levels were higher in patients with baseline serum creatinine ≥1.4 mg/dL (330 [258.5 – 447] versus 186 [152.5 – 253] ng/mL, p<0.0001), while urine NGAL levels were not (p=0.31). In addition, systemic NGAL levels were higher in subjects with history of chronic kidney disease (340 [253 – 445] versus 216 [168 – 303] ng/mL, p=0.003), but urine NGAL levels were not (44 [31 – 85] versus 32 [24 – 98] ng/mL, p=0.227).

Table 2.

Univariate Correlations between Systemic or Urine NGAL Levels and Indices of Renal Impairment for our Acute Decompensated Heart Failure cohort (n=93).

| Variable | Systemic NGAL (ng/mL) | Urine NGAL (ng/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman's r | p-value | Spearman's r | p-value | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | −0.69 | <0.0001 | −0.24 | 0.021 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.68 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | 0.043 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 0.66 | <0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.148 |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

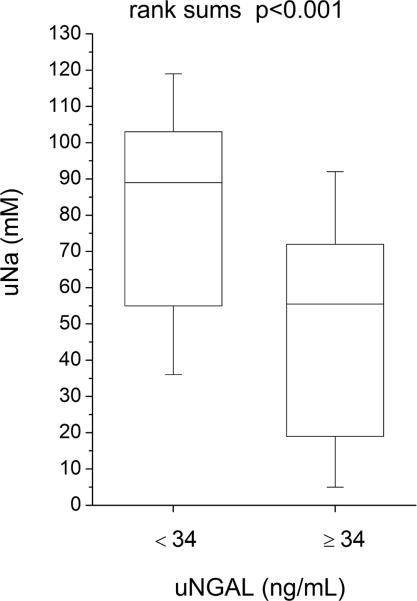

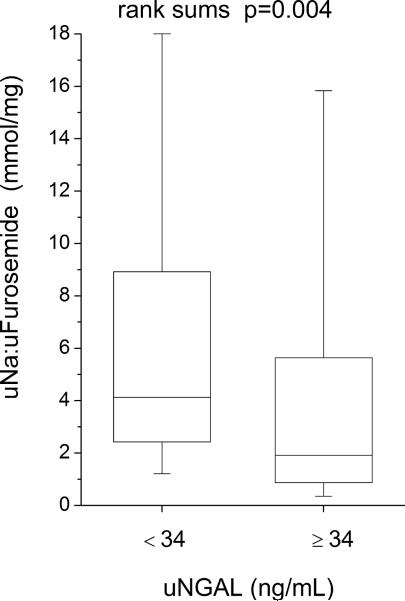

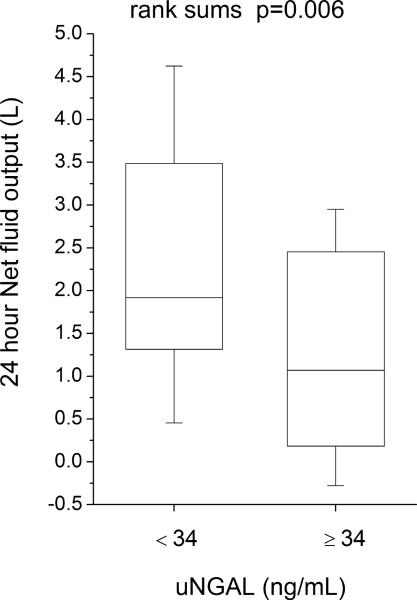

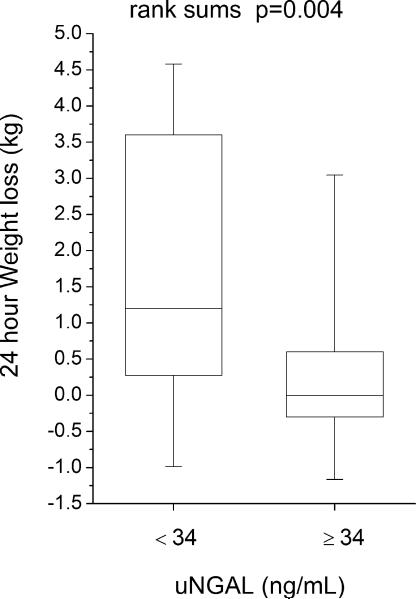

Compared to those with lower (below-median) urine NGAL levels, patients with higher (above-median) urine NGAL levels demonstrated reduced natriuretic response (including lower spot urine sodium [uNa: 56 (18–73) versus 89 (53–105) mM, p<0.001], lower urine sodium to furosemide ratio [uNa: uFurosemide: 1.9 (0.8–6.5) versus 4.1 (2.4–9.6) mmol/mg, p=0.004], lower fractional excretion of sodium [FENa: 1.0 (0.3–2.9) versus 3.0 (1.2–7.3) %-units, p=0.002], lower FENa to urine furosemide ratio [FENa: uFurosemide: 0.04 (0.01–0.23) versus 0.18 (0.05–0.82) %-units·L/ mg, p=0.006)], and reduced diuresis over the 24 hour period following baseline NGAL measurements (including lower 24-hour diuresis [net fluid output 1.3 ± 1.4 versus 2.3 ± 2.0 L, p=0.006] and less 24-hour weight loss [0.4 ± 1.6 versus 1.8 ± 2.6 kg, p=0.004], Figure 2; Table 3). Urine NGAL remained associated with natriuretic and diuretic markers following adjustment for baseline GFR in multivariable linear regression analysis, and in subgroup analysis following stratification by GFR = 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Urine NGAL also remained associated with natriuretic and diuretic markers in heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction (LVEF ≥45% versus <45%) subgroups. In contrast, markers of impaired natriuresis and reduced 24-hour diuresis did not differ across median serum NGAL (p>0.07 for all), and serum NGAL did not correlate with markers of impaired natriuresis and 24 hour diuresis (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Clinical markers of natriuresis and diuresis stratified by median urine NGAL (34 ng/mL). Abbreviations: uFurosemide, urine furosemide; uNa, urine sodium; uNGAL, urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Table 3.

Univariate Correlations between Systemic or Urine NGAL Levels and Indices of Natriuretic and Diuretic Response in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (n=93).

| Variable | Systemic NGAL (ng/mL) | Urine NGAL (ng/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman's r | p-value | Spearman's r | p-value | |

| Natriuretic markers | ||||

| uNa (mM) | −0.04 | 0.752 | −0.36 | 0.001 |

| uNa: uFurosemide (mmol/mg) | 0.01 | 0.942 | −0.37 | 0.002 |

| FENa (%-units) | 0.18 | 0.109 | −0.33 | 0.004 |

| FENa: uFurosemide (%-units·L/ mg) | 0.15 | 0.227 | −0.39 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic markers | ||||

| 24 hour Net fluid output (L) | 0.08 | 0.456 | −0.37 | <0.001 |

| 24 hour Weight loss (kg) | 0.04 | 0.720 | −0.35 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium; uFurosemide, urine furosemide; uNa, urine sodium.

Higher baseline serum NGAL progressively improved at predicting reduced overall diuresis the longer patients were followed from baseline. Above-median serum NGAL predicted reduced diuresis over the 5 day period following baseline (reduced 5 day net fluid output [5.5 ± 6.5 versus 8.2 ± 5.6 L, p=0.041] and reduced 5 day weight loss [2.2 ± 4.2 versus 5.7 ± 3.8 kg, p=0.013]). Similarly, serum NGAL was inversely correlated with 5 day net fluid output (r= −0.30, p=0.038) and 5 day weight loss (r= −0.40, p=0.006).

In our study cohort, 21 (23%) subjects developed AKI within 5 days of baseline. Baseline serum NGAL levels were higher in patients who developed AKI (282 [233 – 461] versus 224 [164 – 328] ng/mL, p=0.022), but urine NGAL levels were not (AKI versus no AKI: 64 [27 – 147] versus 33 [24 – 62] ng/mL, p=0.070). In logistic regression analysis, both elevated systemic and urine NGAL levels predicted the development of AKI (serum NGAL: OR = 1.94 [95% CI: 1.18 – 3.45], p=0.009; urine NGAL: Odds ratio (OR) = 1.65 [95% CI: 1.04 – 2.71], p=0.035). Systemic NGAL ≥250 ng/mL predicted AKI with 76% sensitivity and 54% specificity (AUC 0.67, p=0.008), while urine NGAL ≥64 ng/mL predicted AKI with 52% sensitivity and 76% specificity (AUC 0.64, p=0.014). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, urine NGAL ≥ 64 ng/mL predicted AKI following adjustment for baseline GFR (OR: 2.99 [1.05 – 8.61], p=0.040) or serum creatinine (OR: 3.07 [1.07 – 8.88], p=0.037), but serum NGAL ≥250 ng/mL did not (p>0.12 for both).

DISCUSSION

This is the first report providing a direct head-to-head comparison between systemic (serum) and urine measurements of NGAL with respect to their relation to different aspects of renal physiology. Consistent with prior reports, both elevated systemic and urine NGAL levels were associated with reduced GFR and predicted AKI in our ADHF study cohort. However, the novelty of our findings is that elevated urine NGAL levels more likely reflect renal distal tubular injury with impaired natriuresis and diuresis, while elevated systemic NGAL levels more likely reflect reduced GFR and extra-renal synthesis. Therefore, systemic and urine NGAL levels may reflect distinct underlying renal abnormalities associated with ongoing renal inflammatory and oxidative stress.

Our findings highlight the mechanistic insights of NGAL levels based on the specimens being measured. In the two-compartment model of NGAL trafficking originally proposed by Schmidt-Ott et al.15,16, urine NGAL is proposed to derive predominantly from local renal synthesis of NGAL in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the collecting ducts when under inflammatory and oxidative stress16. In comparison, systemic NGAL is proposed to reflect extra-renal synthesis due to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, which may result in part secondary to the systemic inflammatory transcriptome associated with and that helps regulates renal injury15–20. In support of this 2-compartment model, Mori et al. found that tagged NGAL injected into the circulation would traffic to and be captured by renal proximal tubular endosomes, without appearing in the urine in large quantities (<0.2%)16,21. Similarly, measurement of renal vein NGAL indicated that locally synthesized renal NGAL was not efficiently introduced into the circulation but excreted into the urine16,21. Recent work utilizing an NGAL reporter mouse knockout model has further corroborated this model17. While tubular back-leak of renal NGAL into the systemic circulation, and escape of systemic NGAL into the urine in the setting of saturation of the proximal tubular endocytic pathway or proximal tubule injury or dysfunction have been postulated, neither has yet to be demonstrated to occur to a significant extent17,22.

Local renal inflammation and distal tubular dysfunction may constitute one mechanism of diuretic resistance. Pro-oxidant free radicals and pro-inflammatory cytokines may directly reduce renal sodium excretion, putatively through mechanisms including superoxide-mediated enhancement of sodium/potassium/chloride (Na+/K+/2Cl−) co-transporter and apical Na+/H+ exchanger activity in the thick ascending limb, and TNFα -mediated activation of epithelial sodium channel in distal tubule cells3–9.

There are important clinical implications regarding our findings in comparison to previous reports. Our results demonstrating an association between elevated urine NGAL levels and impaired natriuretic and diuretic response to intravenous furosemide may highlight a clinical role for urine NGAL in identifying patients with refractory diuretic resistance, potentially secondary to dysregulated distal tubular sodium handling. This patient subpopulation may benefit from the use of short-term, adjuvant anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and immunomodulation therapies as proposed in other settings7,23–25. The fact that urine NGAL was not associated with long-term adverse events in the setting of stable heart failure as previously reported26 also implies that adverse consequences may be exacerbated in the acute decompensated setting when aggressive diuretic therapy is being administered. In contrast, systemic NGAL levels were not associated with impaired natriuresis or diuresis in our ADHF cohort. In contrast, systemic NGAL was strongly correlated with reduced GFR and predicted AKI, consistent with prior reports27–30. Although systemic NGAL was positively correlated with urine NGAL in our cohort and is postulated to reflect tubulo-interstitial injury through organ crosstalk or putatively (though less likely) tubular back-leak, the systemic inflammatory and oxidative state of heart failure may significantly elevate systemic NGAL levels independent of renal dysfunction and thereby mask its utility as a marker of local tubulo-interstitial inflammation and oxidative stress. In our cohort, elevated systemic NGAL did progressively improve at predicting reduced diuresis the longer patients were followed from baseline, and predicted AKI, potentially highlighting a role for systemic NGAL in characterizing long-term regulation of renal tubular injury by the systemic inflammatory and immune response. Taken together, these findings may imply that NGAL levels may reflect distinctively different aspects of renal dysfunction when measured in serum and in urine samples. Hence, therapeutic responses to elevated NGAL levels may respond differently to a rise in either and/or both measures.

Our study has several limitations. Systemic and urine NGAL levels were compared with spot urine measurements of natriuresis as opposed to 24-hour urine collections, and were measured after initiation of diuretic therapy. Serum creatinine and measures of diuresis were followed only up to time of discharge or for 5 days. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the 4-variable MDRD study equation and not calculated directly. The relatively small sample size and event rates and the lack of longitudinal follow-up of this study cohort limited our ability to perform more robust multivariable analyses. Although serial systemic and urine NGAL levels were not measured in our study cohort, future work may investigate whether elevations in systemic NGAL levels may precede or predict subsequent elevations in urine NGAL, allowing a further detailed temporal characterization of progression of renal dysfunction in acute cardio-renal syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CTSA UL1-RR024989 and 1R01HL103931-02). Dr. Dupont is supported by a research grant from the Belgian American Educational Foundation (BAEF). Dr. Tang has received research grant support from Abbott Laboratories, and has served as consultant for Medtronic Inc and St. Jude Medical. Other authors have no relationships to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cowley AW., Jr Renal medullary oxidative stress, pressure-natriuresis, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;52:777–786. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Franco M, Tapia E, Quiroz Y, Johnson RJ. Renal inflammation, autoimmunity and salt-sensitive hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou AP, Li N, Cowley AW., Jr Production and actions of superoxide in the renal medulla. Hypertension. 2001;37:547–553. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F957–962. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00102.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juncos R, Garvin JL. Superoxide enhances Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F982–987. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00348.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garvin JL, Ortiz PA. The role of reactive oxygen species in the regulation of tubular function. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;179:225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo PC, Jorde UP. The active role of venous congestion in the pathophysiology of acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiPetrillo K, Coutermarsh B, Soucy N, Hwa J, Gesek F. Tumor necrosis factor induces sodium retention in diabetic rats through sequential effects on distal tubule cells. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1676–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juncos R, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Differential effects of superoxide on luminal and basolateral Na+/H+ exchange in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R79–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00447.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felker GM, O'Connor CM, Braunwald E. Loop diuretics in acute decompensated heart failure: necessary? Evil? A necessary evil? Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:56–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.821785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrestha K, Tang WH. Cardiorenal syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and clinical outcomes. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2010;7:167–174. doi: 10.1007/s11897-010-0025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganda A, Onat D, Demmer RT, Wan E, Vittorio TJ, Sabbah HN, Colombo PC. Venous Congestion and Endothelial Cell Activation in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11897-010-0009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Kalandadze A, Li JY, Paragas N, Nicholas T, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-mediated iron traffic in kidney epithelia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:442–449. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000232886.81142.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Li JY, Kalandadze A, Cohen DJ, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Dual action of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:407–413. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paragas N, Qiu A, Zhang Q, Samstein B, Deng SX, Schmidt-Ott KM, Viltard M, Yu W, Forster CS, Gong G, Liu Y, Kulkarni R, Mori K, Kalandadze A, Ratner AJ, Devarajan P, Landry DW, D'Agati V, Lin CS, Barasch J. The Ngal reporter mouse detects the response of the kidney to injury in real time. Nat Med. 2011;17:216–222. doi: 10.1038/nm.2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurman JM. Triggers of inflammation after renal ischemia/reperfusion. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grigoryev DN, Liu M, Hassoun HT, Cheadle C, Barnes KC, Rabb H. The local and systemic inflammatory transcriptome after acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:547–558. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Hassoun HT, Santora R, Rabb H. Organ crosstalk: the role of the kidney. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:481–487. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328332f69e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori K, Lee HT, Rapoport D, Drexler IR, Foster K, Yang J, Schmidt-Ott KM, Chen X, Li JY, Weiss S, Mishra J, Cheema FH, Markowitz G, Suganami T, Sawai K, Mukoyama M, Kunis C, D'Agati V, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Endocytic delivery of lipocalin-siderophore-iron complex rescues the kidney from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:610–621. doi: 10.1172/JCI23056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devarajan P. Review: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: a troponin-like biomarker for human acute kidney injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Chen H, Zhou C, Ji Z, Liu G, Gao Y, Tian L, Yao L, Zheng Y, Zhao Q, Liu K. Potent potentiating diuretic effects of prednisone in congestive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;48:173–176. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000245242.57088.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu C, Liu G, Zhou C, Ji Z, Zhen Y, Liu K. Potent diuretic effects of prednisone in heart failure patients with refractory diuretic resistance. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:865–868. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70840-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Liu C, Ji Z, Liu G, Zhao Q, Ao YG, Wang L, Deng B, Zhen Y, Tian L, Ji L, Liu K. Prednisone adding to usual care treatment for refractory decompensated congestive heart failure. Int Heart J. 2008;49:587–595. doi: 10.1536/ihj.49.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damman K, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Navis G, Vaidya VS, Smilde TD, Westenbrink BD, Bonventre JV, Voors AA, Hillege HL. Tubular damage in chronic systolic heart failure is associated with reduced survival independent of glomerular filtration rate. Heart. 2010;96:1297–1302. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.194878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aghel A, Shrestha K, Mullens W, Borowski A, Tang WH. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in predicting worsening renal function in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010;16:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori K, Nakao K. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as the real-time indicator of active kidney damage. Kidney Int. 2007;71:967–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolignano D, Lacquaniti A, Coppolino G, Campo S, Arena A, Buemi M. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin reflects the severity of renal impairment in subjects affected by chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2008;31:255–258. doi: 10.1159/000143726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poniatowski B, Malyszko J, Bachorzewska-Gajewska H, Malyszko JS, Dobrzycki S. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a marker of renal function in patients with chronic heart failure and coronary artery disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2009;32:77–80. doi: 10.1159/000208989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]