Abstract

Recent work has identified Behavioral Approach System (BAS) sensitivity as a risk factor for the first onset and recurrence of mood episodes in bipolar disorder, but little work has evaluated risk factors for depression in individuals at risk for, but without a history of, bipolar disorder. The present study evaluated cognitive styles and the emotion-regulatory characteristics of emotional clarity and ruminative brooding as prospective predictors of depressive symptoms in individuals with high versus moderate BAS sensitivity. Three separate regressions indicated that the associations between dysfunctional attitudes, self-criticism, and neediness with prospective increases in depressive symptoms were moderated by emotional clarity and brooding. Whereas brooding interacted with these cognitive styles to exacerbate their impact on depressive symptoms, emotional clarity buffered against their negative impact. These interactions were specific to high-BAS individuals for dysfunctional attitudes, but were found across the full sample for self-criticism and neediness. These results indicate that emotion-regulatory characteristics and cognitive styles may work in conjunction to confer risk for and resilience against depression, and that some of these relationships may be specific to individuals at risk for bipolar disorder.

Keywords: Emotion Regulation, Cognitive Style, Bipolar Disorder, Depression, High-Risk, Behavioral Approach System, Emotional Clarity, Rumination

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by the presence of manic and/or hypomanic episodes, which are distinguished by abnormally high, grandiose, or irritable moods, as well as depressive episodes (Molz & Goldstein, 2011). BD often has a severe course with pervasive effects, including high rates of suicide and divorce (Angst, Stassen, Clayton, & Angst, 2002). Mood episodes experienced by those with BD account for over 96 million days of work loss per year in the United States every year (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). Approximately 4.4% of the population of the United States will experience a bipolar spectrum disorder in their lifetimes (Merikangas et al., 2007). Furthermore, mood episodes in patients with BD occur with a much higher frequency than in patients with unipolar depression (Giles, Rush, & Roffwarg, 1986). Despite this fact, BD is still significantly less researched than other mental disorders (Hyman, 2000). Although recent work has identified factors that increase BD individuals’ risk for hypomanic/manic symptoms (for reviews, see Johnson, 2005; Urosevic, Abramson, Harmon-Jones, & Alloy, 2008), less work has evaluated risk factors for the development of depressive symptoms in BD, despite the fact that major depressive episodes have increased severity, persistence, and cause greater occupational impairment in BD compared to unipolar depression (Kessler et al., 2006).

Cognitive Styles as Vulnerabilities to Depression

Several well-established theories have identified cognitive styles that increase individuals’ risk for unipolar depression, which also may be useful in developing theories of depression in BD (Alloy, Abramson, Walshaw, Keyser, & Gerstein, 2010). These characteristics include dysfunctional attitudes (Beck, 1983; Dozois & Beck, 2008), the depressive personality styles of dependency and self-criticism (Blatt, D’Afflitti, & Quinlan, 1976; Zuroff, Quinlan, & Blatt, 1990), and negative overgeneralization (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Carver, 1998).

Beck’s cognitive theory (Beck, 1967) suggests that negative attitudes and beliefs, or schemas, constitute a vulnerability to depression following negative life events. Specifically, individuals with dysfunctional attitudes are hypothesized to experience an activation of these attitudes in response to stressors. Studies consistently have found that individuals with current depression have higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes than do individuals without depression (e.g., Gotlib, 1984), and that individuals with a history of depression have higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes than do individuals without a history of depression (Alloy et al., 2000). In addition, higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes have been shown to predict the onset of episodes of depression (Rholes, Riskind, & Neville, 1985; Alloy et al., 2006a), which is consistent with the idea that dysfunctional attitudes serve as vulnerabilities to depression.

Blatt et al. (1976) proposed two personality styles thought to serve as vulnerabilities to depression: dependency and self-criticism. Dependency is characterized by an excessive need for interpersonal relationships, feelings of loneliness, and of wanting to be close to or dependent on others (Blatt, Zohar, Quinlan, Zuroff, & Mongrain, 1995); consequently, dependency may lead to depression when the individual is faced with interpersonal stress. Dependency has been shown to be composed of two factors. Specifically, neediness, which is exemplified by a strong desire for frequent support from others, has consistently been shown to be associated with depressive symptoms, whereas connectedness, which is characterized by having and valuing interpersonal relationships, has not been linked to depressive symptoms (Cogswell, Alloy, & Spasojevic, 2006; Rude & Burnham, 1995). The self-criticism component of personality is less interpersonal and more internal. This component is related to feelings of guilt, hopelessness, and of failing to meet expectations. Self-criticism may lead to depression when the individual is faced with threats to self-esteem and self-worth. In longitudinal studies, neediness and self-criticism have been shown to predict depressed mood (Cogswell et al., 2006; Zuroff, Igreja, & Mongrain, 1990).

Beck et al. (1983) proposed related personality styles of sociotropy and autonomy as vulnerabilities for depression, as these two dimensions are thought to reflect personally relevant schemas. Sociotropy, or social dependency, is conceptualized as how invested a person is in positive exchange with another person and is characterized by requiring social feedback for support (Bieling et al., 2000). The sociotropic individual values positive interactions with other people, is interpersonally dependent, and is likely to experience depression as a result of interpersonal disruption. Sociotropy has been found to predict depression in combination with negative life events (Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999). Autonomy is conceptualized as a person’s need for independence and for goal-oriented behavior (Bieling et al., 2000). The autonomous individual is characterized by goal-striving and may become depressed when efforts to achieve goals are thwarted. In interaction with negative achievement events, autonomy has been found to be a less robust predictor of depression (Clark & Beck, 1991). Beck et al.’s (1983) and Blatt et al.’s (1976) theories are hypothesized to parallel one another, with some individuals being characterized by sociotropy and dependency and others characterized by autonomy and self-criticism (Coyne & Whiffen, 1995).

Emotion-Regulatory Vulnerabilities to Depression

In addition to these cognitive risk factors, emotion-regulatory processes have been implicated in depression, including rumination and emotional clarity. Response styles theory contends that individuals who have a tendency to ruminate, or repeatedly and passively think about, the causes and consequences of their depressed mood are vulnerable to experiencing depressive symptoms of greater duration and severity than people who do not ruminate (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Empirical research has supported the hypothesis that this process may occur due to the intense focus on sadness or the causes of depression, which amplifies the effects of maladaptive cognitions (Just & Alloy, 1997; Morrow & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1990; Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Frederickson, 1993; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001). Indeed, in several studies, rumination has been shown to exacerbate the effects of cognitive vulnerabilities on depressive symptoms or episodes (Ciesla, Felton, & Roberts, 2011; Ciesla & Roberts, 2007; Robinson & Alloy, 2003). Thus, rumination is a cognitive strategy used to regulate negative emotion that has the unintended deleterious consequences of maintaining and intensifying depressed mood.

Emotional clarity (EC) is characterized by an awareness and understanding of one’s own emotions and emotional experiences, as well as the ability to properly label them (Gohm & Clore, 2000). High levels of EC have been linked to adaptive coping and positive well-being (Gohm & Clore, 2000). EC also has been shown to protect against depressive symptoms caused by some, but not all, stressors, among older adults (Kennedy et al., 2010). In contrast, low EC predicts maladaptive interpersonal responses to stress and depressive symptoms in youth (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010). In addition, students with high levels of EC show more adaptive problem-solving behavior with complex problems, and better performance on complex tasks than low EC students (Otto & Lantermann, 2006). Thus, there is evidence that EC serves as a protective factor against symptoms of depression.

Cognitive Styles and Emotion-Regulatory Processes as Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder

Similar support for cognitive and emotion-regulatory vulnerabilities associated with depressive symptomatology has been discovered in those with BD (see Alloy et al., 2010 for a review). In terms of emotion characteristics, several studies have found that individuals with BD have higher levels of rumination compared to healthy samples (Alloy et al., 2009a; Gruber, Eidelman, & Harvey, 2008; Gruber et al., in press; Thomas et al., 2007; Van der Gucht et al., 2009), with levels comparable to those of individuals with unipolar depression (Johnson, McKenzie, & McMurrich, 2008). Rumination in BD is associated with depressive symptoms (Van der Gucht et al., 2009), greater lifetime depression frequency (Gruber et al., in press), and has been shown to prospectively predict depressive episodes (Alloy et al., 2009a). Thus, rumination is hypothesized to play a similar role in predicting depressive symptoms in individuals with BD as it does in unipolar depression. No studies to date have examined emotional clarity in individuals with BD.

Cognitive styles also have been found to be elevated in and relevant to BD. Specifically, individuals with BD have elevated levels of dysfunctional attitudes (Alloy et al., 2009b; Scott, Stanton, Garland, & Ferrier, 2000) and self-criticism (Alloy et al., 2009b), both of which have been found to be associated with depressive symptoms in unipolar depression. Dysfunctional attitudes have been found to prospectively predict depressed mood in individuals with BD (Johnson & Fingerhut, 2004). In interaction with congruent life events, self-criticism has been shown to predict symptoms of depression among individuals with BD (Francis-Raniere, Alloy, & Abramson, 2006). However, another study reported that dependency and self-criticism did not predict the likelihood of onset of major depressive episodes in individuals with BD (Alloy et al., 2009b), although this report did not evaluate these styles in the context of life events, which may contribute to the impact of these personality styles on depression.

Although some research has identified risk factors for the development of depressive symptoms in individuals with BD, little work has evaluated vulnerabilities to depression among individuals at risk for, but without a history of BD. Identifying vulnerabilities for depression in individuals at risk for first onset of BD could have preventive implications for reducing risk of mood dysregulation. Therefore, it is important to study these vulnerabilities in people who are at risk of developing BD. One theory of BD that has received much recent support is the BAS hypersensitivity model (Alloy & Abramson, 2010; Alloy, Abramson, Urosevic, Bender & Wagner, 2009c; Depue & Iacono, 1989; Depue, Krauss & Spoont, 1987; Johnson, 2005; Urosevic et al., 2008). The BAS is a motivational system that is linked to goal-striving and approach to rewards (Gray, 1994). Individuals with BD are hypothesized to have a BAS that is overly sensitive and that leads to the development of (hypo)manic symptoms when activated and depressive symptoms when deactivated. Activation of the BAS is likely to occur in response to events involving goal-striving or attainment, and deactivation of the BAS may occur in response to failures or non-attainment of goals (Depue et al., 1987; Fowles, 1988, 1993; Urosevic et al., 2008).

Recent research on the BAS has supported the assertion that high BAS sensitivity is associated with BD (e.g., Alloy et al., 2006b; Salavert et al., 2007). Among individuals with BD, BAS sensitivity has been shown to prospectively predict the development of mood episodes (Alloy et al., 2008), as well as the progression from diagnosis of cyclothymic disorder to bipolar II disorder, and from cyclothymia or bipolar II to full-blown bipolar I disorder (Alloy et al., 2012). Importantly, Alloy et al. (in press) found that high BAS sensitivity also predicted first onset of bipolar spectrum disorders. Thus, BAS sensitivity appears to be an important risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder.

Previous studies evaluating cognitive styles in individuals at risk for BD often have used the Hypomanic Personality Scale (HPS; Eckblad & Chapman, 1986), a measure highly correlated with BAS sensitivity. These studies found patterns of cognitive styles that mirrored those in individuals with BD (Dempsey, Gooding, & Jones, in press; Johnson & Jones, 2009; Knowles, Tai, Christensen, & Bentall, 2005; Thomas & Bentall, 2002), although these studies did not screen out individuals with a history of (hypo)manic episodes. Thus, it seems that both individuals with a history of BD and those at risk for the development of BD exhibit some negative cognitive styles that are also seen in individuals with unipolar depression. However, few, if any, studies have prospectively evaluated vulnerabilities to depressive symptoms among individuals determined to be at risk for developing a first onset of BD.

The Present Investigation

In the present study, we used a prospective behavioral high-risk design (Alloy et al., 2006a,b; Riskind & Alloy, 2006) to evaluate cognitive styles and emotion regulation characteristics in a sample of adolescents who were found to be at high or low risk for BD based on having high or moderate BAS sensitivity (Alloy et al., in press). We chose a moderate-BAS group, as opposed to a low-BAS group, to serve as a comparison group because a moderate-BAS group is closer to the mean on the BAS sensitivity dimension and is therefore more normal from a statistical perspective, and because low BAS has been associated with risk for unipolar depression (but not bipolar disorder) in prior studies (see Alloy et al., 2006b, in press; Depue & Iacono, 1989; Depue et al., 1987). Adolescents (ages 14-19) were chosen because this has been identified as the period during which individuals are at greatest risk for the first onset of the adult form of BD (Alloy, Abramson, Walshaw, Keyser, & Gerstein, 2006b; Burke, Burke, Regier, & Rae, 1990; Kennedy et al., 2005; Kessler, Rubinow, Holmes, Abelson, & Zhao, 1997; Kupfer et al., 2002; Weissman et al., 1996). In particular, we investigated whether rumination and emotional clarity would moderate the relationship between cognitive vulnerabilities and prospective increases in depressive symptoms, particularly in the high-BAS group. We hypothesized that rumination would exacerbate the effect of maladaptive cognitive styles, as demonstrated in previous studies of depressive symptoms. We also hypothesized that emotional clarity would serve as a buffer against the deleterious effects of negative cognitive styles, because having an awareness and understanding of one’s own emotional experiences might allow one to identify symptoms of depression and, therefore, to problem-solve or cope with these symptoms more effectively.

Method

Participants

Sample recruitment

Adolescents from Philadelphia area public high schools and colleges (ages 14-19) were selected for Project TEAM (Teen Emotion and Motivation) based on a two-phase screening procedure (Figure 1). In Phase I, 9,991 students were screened following the procedures in Alloy et al. (2006, in press) with a demographics measure and two self-report BAS sensitivity measures: the Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System (BIS/BAS) Scales (Carver & White, 1994) and Sensitivity to Punishment/Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ; Torrubia, Avila, Molto, & Caseras, 2001). Students who scored in the highest 15th percentile on both the BAS-Total score of the BIS/BAS Scales and the Sensitivity to Reward (SR) scale of the SPSRQ were categorized as High BAS (HBAS). Students who scored between the 40th and 60th percentiles on both measures were categorized as Moderate BAS (MBAS).

Figure 1.

Study design and assessment schedule.

A random subsample of the adolescents who met the criteria for HBAS or MBAS status were invited for Phase II screening (n = 390). Parental consent and adolescents’ assent was obtained for participants under the age of 18, whereas participants 18 and over provided their own consent. In Phase II, participants were administered the mood and psychosis sections of an expanded Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Lifetime (exp-SADS-L) interview, as well as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Rush, Shaw & Emery, 1979) to assess depressive symptoms and the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM; Altman, Hedeker, Peterson, & Davis, 1997) to assess hypomanic/manic symptoms. Participants were excluded from the final sample if they met DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) or Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC; Spitzer et al., 1978) criteria for any disorder in the bipolar spectrum (bipolar I or II, cyclothymia, or bipolar NOS) with onset prior to the date of the participant’s completion of the Phase I screening measures, if they met criteria for any lifetime psychotic disorder, or could not write or speak fluent English. Of the eligible sample, 22 participants were excluded because they met criteria for a bipolar spectrum disorder with onset prior to their Phase I screening, seven were excluded because they met criteria for a psychotic disorder, and five were excluded due to poor English. In addition, 66 eligible Phase II students did not complete their baseline assessment and, thus, were not included in the present analyses. Participants in the final sample were representative of the original Phase I screening sample and did not differ from Phase II – eligible participants who did not complete the baseline assessment (see Alloy et al., in press for detailed representativeness analyses).

Study sample

The current sample consisted of 98 HBAS participants and 63 MBAS participants who had completed the Phase II screening and a follow-up visit (see Table 1 for sample demographic characteristics and BIS/BAS, SPSRQ, and BDI scores).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

| High BAS (N = 98) |

Moderate BAS (N = 63) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.15 (1.58) | 17.99 (1.56) |

| Sex | 62.3% Female | 72.0% Female |

| Race | 55.6% Caucasian | 47.2% Caucasian |

| 21.2% African American | 36.1% African American | |

| 14.1% Asian/Pacific Islanders | 13.9% Asian/Pacific Islanders | |

| 2.0% Biracial | 0.0% Biracial | |

| 4.0% Other | 4.7% Other | |

| Ethnicity | 8.1% Hispanic/Latino | 5.6% Hispanic/Latino |

| BIS | 20.01 (4.17) | 19.46 (2.90) |

| BAS-T* | 46.00 (2.73) | 38.13 (0.87) |

| SP | 10.89 (5.36) | 11.08 (5.02) |

| SR* | 18.16 (1.90) | 11.30 (2.19) |

| BDI (Time 1) | 6.88 (6.77) | 5.59 (5.30) |

| BDI (Follow-up) | 5.74 (6.62) | 4.28 (6.26) |

| MDE History | 39.3% | 29.2% |

p < .05.

Note. Standard deviations are in parentheses. BIS = Behavioral Inhibition System scores from the BIS/BAS Scales; BAS-T = Behavioral Approach System – Total scores from the BIS/BAS Scales; SP = Sensitivity to Punishment scores from the SPSRQ; SR = Sensitivity to Reward from the SPSRQ; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; ASRM = Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale; MDE = Major Depressive Episode.

Procedures

After completing the screening processes, participants completed an initial session involving further interviews and questionnaires. All participants who completed the initial assessment were followed prospectively for an average of 274 days between assessments. At follow-up, participants completed self-report instruments to evaluate symptom levels.

Measures

BAS Sensitivity Measures

The Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System Scales (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994) were one of the two measures used to determine group selection. The self-report BIS/BAS scales are frequently used to assess individual differences in BIS and BAS sensitivity. Participants are asked to respond to 20 questions on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). A BAS total score was used and calculated by summing all BAS items, with higher scores indicating higher BAS sensitivity. The BIS/BAS scales have demonstrated good internal consistency and retest reliability (Carver & White, 1994). In addition, construct validity was evidenced by concurrent associations with prefrontal cortical activity, affect, personality traits, and reaction-time performance on learning tasks (Colder & O’Conner, 2004; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997; Kambouroupolis & Staiger, 2004; Sutton & Davidson, 1997; Zinbarg & Mohlman, 1998). The internal consistency of the BAS total scale in Phase I screening was α = .80.

The Sensitivity to Punishment/Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ; Torrubia, Avila, Molto, & Caseras, 2001) is a 48-item self report measure used to assess an individual’s sensitivity to reward (SR) and punishment (SP) with 24 items for each subscale. The SPSRQ was designed to be more theoretically consistent with Gray’s BIS/BAS theory, to have greater construct validity, and to improve on weaknesses in the BIS/BAS scale’s content. The SPSRQ was used in conjunction with the BIS/BAS scale to determine group status. Both subscales have demonstrated good internal consistency and retest reliability (Torrubia et al., 2001). In Phase I of the current study, the SR and SP demonstrated good internal consistency with α’s = .76 and .84, respectively, and SR correlated with the BAS total in Phase I (r = .40).

Depressive symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1979) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the presence and severity of cognitive, affective, motivational, and somatic symptoms of depression. The BDI has been found to have good internal consistency (α’s = .81-.86) and retest reliability (r’s = .48-.86) in both clinical and nonclinical samples and has been validated in student samples (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988). In the present study, this measure was given at Time 1 and at follow-up with α’s = .89 and .92, respectively.

Dysfunctional attitudes

The Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS; Weissman & Beck, 1978) is a 40-item self-report questionnaire that assesses dysfunctional beliefs regarding concerns about others’ approval and performance expectations. Participants are asked to respond to 7-point Likert scales ranging from totally agree to totally disagree regarding descriptions of their attitudes most of the time (e.g., “My value as a person depends greatly on what others think of me” and “If I fail partly, it is as bad as being a complete failure”). The DAS has demonstrated good construct validity (Alloy et al., 2000; Francis-Raniere et al., 2006; Segal et al., 1999). The DAS was given at Time 1 with an internal consistency of α = .86.

Depressive personality

The Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ; Blatt, D’Aflitti, & Quinlan, 1976) is a 66-item self-report questionnaire that measures depressive personality styles described by Blatt et al. (1976). Participants rated how much they agree with statements about their personality on 7-point scales (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). The DEQ is composed of two primary subscales that were of interest in the present study: Self-Criticism (e.g., “I have a difficult time accepting weaknesses in myself”) and Dependency, which contains two subscales, Connectedness (e.g., “I constantly try, and very often go out of my way, to please or help people I am close to”), and Neediness (e.g., “Without support from others who are close to me, I would be helpless”). The DEQ has demonstrated high internal and retest reliability (Blatt et al., 1976; Zuroff, Moskowitz, Wielgus, Powers, & Franko, 1983) and the factors have shown good construct validity. In the present study, the DEQ was given at Time 1. The internal consistencies of the subscales used in the present study were as follows: Self-Criticism α = .78, Dependency α = .75, Neediness α = .72, and Connectedness α = .80.

Rumination

The Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the extent to which participants engage in neutrally-focused introspection (i.e., reflection) and “moody pondering” (i.e., brooding) in response to their depressed mood. Participants are asked to rate how often they participate in certain responses to their depressed mood, on 4-point Likert scales ranging from 1 = almost never to 4 = almost always. Sample items from the two subscales include “Analyze recent events to try to understand why you are depressed” (brooding) and “Think about a recent situation, wishing it had gone better” (reflection). Brooding (RRS-BR) has been found to better predict depressive symptoms over time than Reflection (Treynor et al., 2003), and thus was of interest in the present study. In previous studies, the RRS-BR has demonstrated good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Treynor et al., 2003). In the present study, the RRS-BR was given at Time 1 and demonstrated good internal consistency, α = .76.

Emotional Clarity

The Emotional Clarity questionnaire (EC; Flynn & Rudolph, 2010) is a measure adapted from an instrument used with adults (TMMS; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995) that assesses emotional clarity. The EC is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that asks participants to rate the way they experience their feelings (e.g., “I usually know how I am feeling” and “I usually understand my feelings”) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Item scores are summed with higher scores indicating greater emotional clarity. The EC has demonstrated good internal consistency and convergent validity with behavioral measures involving the identification of facial expressions (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010). In the current study, the EC demonstrated adequate internal consistency, α = .71.

Results

Table 2 displays bivariate correlations between EC, Brooding, cognitive styles, BAS risk group, and depressive symptoms. EC and Brooding were negatively correlated, indicating that higher levels of Brooding were associated with lower levels of EC. EC was negatively correlated with Time 1 and follow-up BDI, and Brooding was positively correlated with BDI scores, indicating that depressive symptoms were associated with high levels of Brooding and low levels of EC. In general, each of the negative cognitive styles correlated positively with brooding and negatively with EC.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between All Primary Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 EC | --- | |||||||

| 2 RRS-BR | −.25** | --- | ||||||

| 3 BAS | −.03 | −.18* | --- | |||||

| 4 DAS | −.34*** | .43*** | −.16* | --- | ||||

| 5 DEQ N | −.09 | .43*** | −.11 | .45*** | --- | |||

| 6 DEQ SC | −.43*** | .57*** | −.11 | .53*** | .51*** | --- | ||

| 7 BDI - T1 | −.37*** | .48*** | −.10 | .43*** | .28*** | .59*** | --- | |

| 8 BDI – Follow-up | −.33*** | .37*** | −.11 | .22** | .29*** | .49*** | .56*** | --- |

| Mean | 1.71 | 11.92 | n/a | 125.98 | 0.34 | −0.23 | 5.28 | 6.46 |

| SD | 0.81 | 3.67 | n/a | 30.10 | 0.61 | 1.04 | 6.85 | 6.51 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Note. EC = Emotional Clarity; RRS-BR = Ruminative Response Scale - Brooding Subscale; BAS = Behavioral Approach System Risk Group (0 = High-BAS, 1 = Moderate-BAS); DAS Total = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale - Total Score; DEQ N = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire - Neediness Subscale; DEQ SC = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire - Self-Criticism Subscale; BDI - T1 = Beck Depression Inventory Score at Time 1; BDI – Follow-up = Beck Depression Inventory Score at follow-up.

To evaluate whether DAS, in interaction with EC or Brooding, predicted depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for initial depressive symptoms, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions. Predictor variables (DAS, EC, and Brooding) were centered at their means prior to analysis, and BAS risk group was dummy coded, with 0 indicating the high-BAS group and 1 indicating the moderate-BAS group (Aiken & West, 1991). To test our hypotheses, we regressed follow-up BDI scores on a number of predictor variables (see Tables 3 and 4). In Step 1, Time 1 BDI scores were entered, thus creating a residual score reflecting change in depressive symptoms from Time 1 to follow-up. In Step 2, main effects of BAS risk group, a cognitive style, and either Brooding or EC were entered. In Step 3, the two-way interaction terms between each of the predictors were entered. Finally, in Step 4, the three-way interaction term between BAS risk group, the cognitive style, and either Brooding or EC was entered.

Table 3.

Interactions between Cognitive Styles, Emotional Clarity, and Behavioral Approach System Group Predicting Depressive Symptoms at Follow-Up, Controlling for Time 1 Depressive Symptoms

| Step | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 – Dysfunctional Attitudes as Focal Predictor | ||||

| 1 | BDI (Time 1) | 0.48 | 5.99*** | .33*** |

| 2 | EC | −0.02 | −0.22 | .02 |

| BAS | −0.03 | −0.41 | ||

| DAS | 0.06 | 0.50 | ||

| 3 | DAS × EC | −0.29 | −3.32*** | .04* |

| BAS × EC | −0.15 | −1.70 | ||

| BAS × DAS | −0.15 | −1.51 | ||

| 4 | DAS × EC × BAS | 0.23 | 2.52* | .03* |

| Model 2 – Self-Criticism as Focal Predictor | ||||

| 1 | BDI (Time 1) | 0.33 | 3.81*** | .33*** |

| 2 | EC | 0.09 | 0.87 | .05* |

| BAS | −0.17 | −1.36 | ||

| DEQ SC | −0.55 | −0.65 | ||

| 3 | DEQ SC × EC | −0.36 | −3.27*** | .06** |

| BAS × EC | −0.15 | −1.60 | ||

| BAS × DEQ SC | 0.43 | 0.93 | ||

| 4 | DEQ SC × EC × BAS | 0.60 | 1.12 | .01 |

| Model 3 – Neediness as Focal Predictor | ||||

| 1 | BDI (Time 1) | 0.46 | 6.01*** | .33*** |

| 2 | EC | −0.04 | −0.44 | .04* |

| BAS | −0.07 | −0.94 | ||

| DEQ N | 0.27 | 2.64** | ||

| 3 | DEQ N × EC | −0.16 | −2.20* | .04* |

| BAS × EC | −0.15 | −1.63 | ||

| BAS × DEQ N | −0.21 | −2.03* | ||

| 4 | DEQ N × EC × BAS | −0.05 | −0.69 | <.01 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Note. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory score; EC = Emotional Clarity; BAS = Behavioral Approach System Risk Group (0 = High-BAS, 1 = Moderate-BAS); DAS Total = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale - Total Score; DEQ SC = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire - Self-Criticism Subscale; DEQ N = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire - Neediness Subscale.

Table 4.

Interactions between Cognitive Styles, Brooding, and Behavioral Approach System Group Predicting Depressive Symptoms at Follow-Up, Controlling for Time 1 Depressive Symptoms

| Step | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 – Dysfunctional Attitudes as Focal Predictor | ||||

| 1 | BDI (Time 1) | 0.46 | 5.88*** | .32*** |

| 2 | RRS-BR | 0.14 | 1.54 | .02 |

| BAS | 0.01 | 0.13 | ||

| DAS | −0.05 | −0.51 | ||

| 3 | DAS × RRS-BR | 0.27 | 3.18** | .03 |

| BAS × RRS-BR | 0.03 | 0.32 | ||

| BAS × DAS | −0.08 | 0.83 | ||

| 4 | DAS × RRS-BR × BAS | −0.21 | −2.25* | .02* |

| Model 2 – Self-Criticism as Focal Predictor | ||||

| 1 | BDI (Time 1) | 0.35 | 4.33*** | .32*** |

| 2 | RRS-BR | 0.05 | 0.46 | .04* |

| BAS | −0.02 | −0.26 | ||

| DEQ SC | 0.13 | 1.18 | ||

| 3 | DEQ SC × RRS-BR | 0.26 | 3.28*** | .06** |

| BAS × RRS-BR | −0.04 | −0.41 | ||

| BAS × DEQ SC | 0.12 | 1.19 | ||

| 4 | DEQ SC × RRS-BR × BAS | −0.07 | −0.73 | <.01 |

| Model 3 – Neediness as Focal Predictor | ||||

| 1 | BDI (Time 1) | 0.49 | 6.52*** | .32*** |

| 2 | RRS-BR | 0.03 | 0.28 | .02 |

| BAS | −0.03 | −0.48 | ||

| DEQ N | 0.11 | 1.07 | ||

| 3 | DEQ N × RRS-BR | 0.25 | 2.57* | .04* |

| BAS × RRS-BR | 0.04 | 0.47 | ||

| BAS × DEQ N | −0.08 | −0.76 | ||

| 4 | DEQ N × RRS-BR × BAS | −0.07 | −0.74 | <.01 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Note. BDI - T1 = Beck Depression Inventory Score at Time 1; RRS-BR = Ruminative Response Scale - Brooding Subscale; BAS = Behavioral Approach System Risk Group (0 = High-BAS, 1 = Moderate-BAS); DAS Total = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale - Total Score; DEQ SC = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire - Self-Criticism Subscale; DEQ N = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire - Neediness Subscale.

Dysfunctional Attitudes

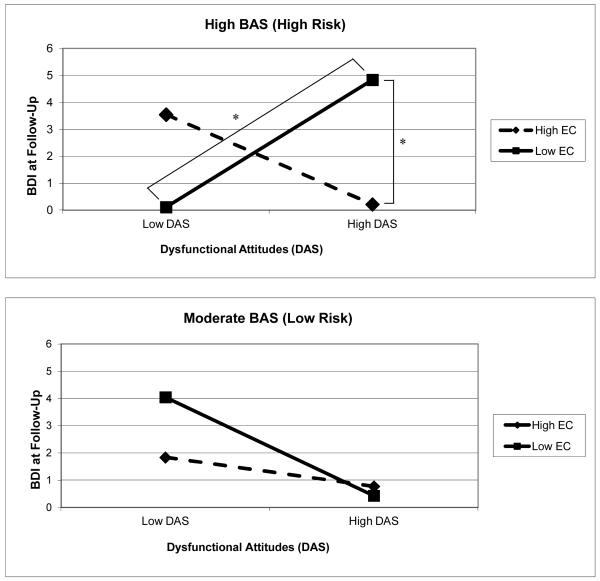

First, we evaluated whether dysfunctional attitudes interacted with EC to predict depressive symptoms at follow-up, and whether this effect was distinct to high-BAS individuals. A significant 3-way interaction emerged between BAS risk group, DAS, and EC predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (Table 3, Figure 2). Consistent with hypotheses, there was a two-way interaction between DAS and EC that was significant only for the high-BAS group. In the high-BAS group, among individuals higher in EC, there was no effect of DAS, t = −1.24, p = .22. However, at lower levels of EC, there was a significant effect of DAS, t = 3.11, p < .005, such that higher DAS predicted increases in depressive symptoms at follow-up. At higher levels of DAS, there was also a significant effect of EC, t = −2.80, p < .01, such that lower levels of EC predicted increases in depressive symptoms. The effect of EC at lower levels of DAS was not significant, t = 1.70, p = .09.

Figure 2.

Three-way interaction between dysfunctional attitudes, emotional clarity (EC), and BAS risk group predicting follow-up depressive symptoms (BDI), controlling for initial depressive symptoms (BDI). * p < .05.

A significant 3-way interaction also emerged between BAS risk group, DAS and Brooding predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (Table 4, Figure 3). Again, there was a two-way interaction between DAS and Brooding that was significant only for the high-BAS group. In the high-BAS group, among individuals higher in Brooding, there was a significant effect of DAS, t = 2.05, p = .04, such that DAS predicted increases in depressive symptoms at follow-up. At lower levels of Brooding, higher levels of DAS predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms, t = −2.01, p < .05. At higher levels of DAS, there was also a significant effect of Brooding, t = 3.80, p < .001, such that higher levels of Brooding predicted increases in depressive symptoms. There was no effect of Brooding at lower levels of DAS, t = −0.80, p = .43.

Figure 3.

Three-way interaction between dysfunctional attitudes, brooding, and BAS risk group predicting follow-up depressive symptoms (BDI), controlling for initial depressive symptoms (BDI). * p < .05.

In sum, EC and Brooding appeared to have the greatest impact on depressive symptoms among high-BAS individuals with high levels of dysfunctional attitudes. Correspondingly, dysfunctional attitudes were the most detrimental among high-BAS individuals with high levels of Brooding and low levels of EC.

Self-Criticism

DEQ Self-Criticism interacted with EC significantly to predict depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (see Table 3; Figure 4). There was not a significant 3-way interaction between Self-Criticism, EC, and BAS group, indicating that this interaction did not differ between risk groups. At higher levels of EC, there was no effect of Self-Criticism, t = 0.71, p = .48. However, at lower levels of EC, there was a significant effect of Self-Criticism, t = 2.88, p < .01, such that higher Self-Criticism predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up.

Figure 4.

Two-way interactions between Emotional Clarity and Self-Criticism or Neediness predicting follow-up depressive symptoms (BDI), controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (BDI). * p < .05.

DEQ Self-Criticism also interacted significantly with Brooding to predict depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (see Table 4; Figure 5). There was not a significant 3-way interaction between Self-Criticism, Brooding, and BAS group, indicating that this interaction did not differ between risk groups. At higher levels of Brooding, there was a significant effect of Self-Criticism, t = 3.16, p < .005, such that higher Self-Criticism predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up. At lower levels of Brooding, there was no effect of Self-Criticism, t = −0.62, p = .54. Additionally, at higher levels of Self-Criticism, there was a significant effect of Brooding, t = 2.94, p < .005, such that higher levels of Brooding predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms. At lower levels of Self-Criticism, there was no effect of Brooding, t = −1.32, p = .19.

Figure 5.

Two-way interactions between Brooding and either Self-Criticism or Neediness, predicting follow-up depressive symptoms (BDI), controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (BDI). * p < .05.

Neediness

DEQ Neediness interacted with EC significantly to predict depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (see Table 3; Figure 4). There was not a significant 3-way interaction between Neediness, EC, and BAS group, indicating that this interaction did not differ between risk groups. At higher levels of EC, there was no effect of Neediness, t = −0.03, p = .98. However, at lower levels of EC, there was a significant effect of Neediness, t = 3.16, p < .005, such that higher Neediness predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up. Additionally, at high levels of Neediness, there was a significant effect of EC, t = −2.54, p = .01, such that higher EC predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms. At low levels of Neediness, there was no effect of EC, t = 0.73, p = .47.

DEQ Neediness also interacted significantly with Brooding to predict depressive symptoms at follow-up, controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms (see Table 4; Figure 5). There was not a significant 3-way interaction between Neediness, Brooding, and BAS group, indicating that this interaction did not differ between risk groups. At higher levels of Brooding, there was a significant effect of Neediness, t = 2.86, p = .005, such that higher Neediness predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up. At lower levels of Brooding, there was no effect of Neediness, t = −0.66, p = .51. Additionally, at higher levels of Neediness, there was a significant effect of Brooding, t = 2.60, p = .01, such that higher levels of Brooding predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms. At lower levels of Neediness, there was no effect of Brooding, t = −0.86, p = .39.

In sum, EC and Brooding appeared to have the greatest effects among individuals high in Self-Criticism and Neediness, with EC buffering against and Brooding exacerbating depressive symptoms, and these results did not differ between BAS risk groups.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the roles of ruminative brooding and emotional clarity, both characteristics implicated in emotion regulation, in relation to various cognitive vulnerabilities in predicting symptoms of depression in a sample of individuals at high or low risk for developing bipolar disorder. As hypothesized, results indicated that low levels of emotional clarity conferred risk for developing symptoms of depression in individuals with various maladaptive cognitive styles. Similarly, results suggested that brooding also conferred a risk for developing symptoms of depression in individuals with negative cognitive styles. However, only the interactions with dysfunctional attitudes were specific to the high-BAS group; interactions with self-criticism and neediness did not differ between risk groups. Taken together, these results suggest that the presence of dysfunctional attitudes, low levels of emotional clarity, and high levels of brooding may be especially harmful in adolescents at risk for bipolar disorder and may place them at risk for developing symptoms of depression. Although previous reports have indicated that levels of self-criticism are higher in individuals at risk for bipolar disorder (Rosenfarb, Becker, Khan, & Mintz, 1998), the results of the present study indicate that self-criticism and neediness may be more general, transdiagnostic risk factors for depressive symptoms when experienced in combination with brooding or low emotional clarity. Although emotional clarity and brooding are both constructs related to emotion regulation, only 6 percent of variance was shared between the two measures in this study, thus supporting the idea that they each represent distinct processes.

Rumination has been widely studied as a risk factor for both unipolar depression and symptoms of depression in bipolar disorder, and has been shown to exacerbate the impact of negative cognitive styles on depressive symptoms, presumably because of an increased focus on the negative beliefs that cause depression (Ciesla et al., 2011; Ciesla & Roberts, 2007; Robinson & Alloy, 2003). Emotional clarity, however, has been studied as a risk factor only for unipolar depression. To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the role of emotional clarity in relation to symptoms of depression in individuals shown to be at risk for developing bipolar disorder. Previous studies have shown that individuals with low emotional clarity are more likely to develop symptoms of depression than individuals with high emotional clarity. As suggested by Salovey et al. (1995), individuals high in emotional clarity may be spending little time engaging in maladaptive ruminative processes. That is, individuals who are clear about their feelings may not feel the need to ruminate in order to differentiate them. Consequently, these individuals may use their cognitive resources for adaptive strategies such as coping and minimizing the impact of stressful events. In the context of this study, combining the effect of low emotional clarity with maladaptive cognitive styles may maintain and exacerbate negative affect. In addition, it may be possible that brooding is a result of low emotional clarity. That is, individuals low in emotional clarity have trouble identifying their emotions and are more ambivalent about them, leading them to engage in brooding in order to make sense of their emotional state. However, existing research suggests that rumination may be counterproductive in that it actually blocks or inhibits awareness of one’s emotional state (e.g., Watkins, 2008), which may lead to continued ineffective coping and problem-solving. In addition to blocking EC, brooding may represent a more verbal form of processing emotions which further recruits latent dysfunctional schemas to interpret these emotions. In contrast, emotional clarity is involved in awareness of one’s emotions that may be sustained in order to understand them, potentially via the recruitment of more productive schemas. Thus, EC and rumination may serve as catalysts of negative thought (e.g., Ciesla et al., 2011) in the relationship between negative beliefs and depression. Future work should seek to evaluate more precisely the similarities between these constructs.

It is also important to note the differences in the interactions between cognitive and emotion-regulatory vulnerabilities found between BAS risk groups. We found a significant three-way interaction between BAS risk group, dysfunctional attitudes, and EC and Brooding that was significant for the high-BAS group, but not for the moderate-BAS group. This finding may be understood from within the context of the BAS dysregulation theory of BD, which suggests that individuals with high BAS sensitivity are likely to experience frequent fluctuations in mood as a result of activation or deactivation of the BAS (Alloy & Abramson, 2010; Urosevic et al., 2008). Thus, high-BAS individuals may experience more frequent BAS deactivation by negative life events, which elicits the activation of dysfunctional attitudes. When these activated dysfunctional attitudes are experienced in the context of low emotional clarity or brooding, individuals may experience increased self-focus on the negative cognitive content of these dysfunctional attitudes, which may lead to depressed mood. Individuals with moderate BAS sensitivity may not experience deactivation that is as frequent or severe, thus diminishing the deleterious impact of dysfunctional attitudes, EC, and brooding. In contrast, although we found significant two-way interactions when assessing the risk factors of self-criticism and neediness in the context of the emotion-regulatory characteristics of EC and brooding, the absence of significant three-way interactions with BAS group indicates that the relationships between these risk factors did not differ between high-BAS and moderate-BAS participants. This suggests the possibility that as cognitive personality constructs, self-criticism and neediness may have an impact on depressed mood regardless of whether they are activated by negative events, which may explain why they are relevant in explaining depressed mood when in combination with low EC and high levels of brooding, regardless of BAS sensitivity. Future studies should more directly evaluate these hypothesized processes in combination with negative life events. It is also possible that there is a threshold after which dysfunctional attitudes become particularly problematic. Individuals with high BAS sensitivity had higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes (see Table 2); therefore, it is possible that EC and brooding did not interact with dysfunctional attitudes in the moderate-BAS group because levels of dysfunctional attitudes were low enough to not be particularly impairing, even in combination with low EC or high levels of brooding.

Several additional findings were also notable. Consistent with our hypotheses, dysfunctional attitudes, self-criticism, and neediness appeared to serve as risk factors that were moderated in the expected direction by EC and brooding. Thus, these factors may serve as particular cognitive vulnerabilities to clinical depression among individuals who brood about the cause of negative moods, or who are unclear about their emotional state. Of note, with the exception of ruminative brooding (Alloy et al., 2009a), to our knowledge, none of the vulnerabilities evaluated in the present study have been shown to prospectively predict depressive symptoms in individuals with, or at risk for, BD. Future work with clinical samples should further evaluate these mechanisms to determine whether similar processes are particularly relevant in BD, or if they may be more transdiagnostic risk factors for depression.

Although the interaction of dysfunctional attitudes with EC and brooding in the high-risk group were hypothesized, the form of the interaction was not entirely as anticipated. Specifically, although among high-BAS individuals with higher levels of brooding, higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes predicted increases in depressive symptoms as expected, among such individuals with lower levels of brooding, higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes predicted decreases in depressive symptoms. One possible explanation for this finding is that individuals with lower levels of brooding who also had lower dysfunctional attitudes may have exhibited more extreme positive beliefs (i.e., “totally disagree” with a dysfunctional attitude) on the DAS measure. Although individuals with lower dysfunctional attitudes scores would typically be expected to have lower vulnerability to depression, several studies have found that rigid or extreme levels of positive beliefs (which are likely to be associated with lower dysfunctional attitudes scores) predict depressive relapse (Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001). Nevertheless, the significant effect of brooding at higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes in predicting depressive symptoms indicates that it may be particularly maladaptive for individuals at risk for BD to ruminate when the content of their thoughts is already negative.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the assessments were all self-report questionnaires. Self-report questionnaires are widely used measures of psychopathology, but consistently questioned as valid assessments (Vazire & Mehl, 2008). It is possible that the shared conceptual and methodological variation in the measures used in this study obfuscated our ability to very effectively evaluate these theoretical models. Researchers have called for concurrent measurement by other reporters (Vazire & Mehl, 2008; Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2009) or by more objective interviews (e.g., McQuaid et al., 1992) to combat possible reporter bias. Nonetheless, researchers suggest that self-report measures may not be inherently invalid (Haeffel & Howard, 2010), and in some cases, not significantly different than other methods of assessment (Wagner, Abela, & Brozina, 2005); thus the use of self-report measures at this stage of investigation seems reasonable, but future research should consider also using behavioral methods of investigating the constructs presented here. Additionally, our measure of EC essentially evaluated adolescents’ perceptions of their own EC. It is possible that adolescents with lower actual EC were less accurate at perceiving and reporting their actual EC, which could have clouded our interpretation of the EC measure. Future studies should consider additional methods for more objectively evaluating EC as a protective factor against depression.

Second, although this study replicated previous studies that found that EC is associated with lower depressive symptoms, it is not entirely apparent what regulatory processes may allow EC to have protective effects on mood. Previous work has suggested that problem-solving abilities associated with EC may explain its association with depression (Otto & Lantermann, 2006). As Salovey et al. (1995) suggest, it is also possible that having high EC allows people to pay less attention to negative emotions once they recognize that they exist. Future research should investigate these and other possible explanations for the present results in greater detail. Third, it is unclear whether these results necessarily generalize to individuals with bipolar disorder. Future work should investigate this possibility. Fourth, although the selection of high-BAS and moderate-BAS groups allowed us to compare a group at risk for BD to a group at low risk for BD, we did not include a low-BAS comparison group in the study. Thus, it is unclear whether these results would be applicable to individuals with low BAS sensitivity who may be at risk specifically for unipolar depression (Depue & Iacono, 1989; Depue et al., 1987). Fifth, the study was limited by a two-timepoint design which precluded the use of more sophisticated and potentially more reliable statistical analyses. Additionally, with a larger sample size we may have been able to estimate a single, more comprehensive path-analytic model, rather than conducting separate multivariate analyses for each measure of cognitive style. It also is unclear whether our findings would remain consistent if we had used a shorter follow-up interval. Finally, the range of scores for cognitive styles may be restricted for the DAS, self-criticism, and brooding, each of which have been shown to be correlated with BAS sensitivity (Stange et al., in press). Nevertheless, the consistent moderating effects of brooding and EC on the associations between the cognitive styles and prospective depressive symptoms are unlikely to have been affected meaningfully by the restriction of range.

In sum, emotional clarity and brooding seem to be important factors in providing resilience and risk among individuals with cognitive vulnerabilities to depression. In particular, having high levels of dysfunctional attitudes in combination with low levels of emotional clarity or high levels of brooding may be particularly deleterious among individuals at risk for developing a first onset of BD by virtue of exhibiting high BAS sensitivity. Future work should explore whether the interactions among these factors predict actual episodes of depression in individuals at risk for bipolar disorder and whether these relationships can be replicated in individuals with an existing diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Given the importance of negative life events in the depression literature, these results should also be expanded to include interactions with life stressors. In the meantime, interventions should be developed for individuals at risk for BD to improve understanding of one’s emotions without ruminative brooding, particularly among those individuals with dysfunctional beliefs about themselves or their world.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH 77908 to Lauren B. Alloy.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. The role of the Behavioral Approach System (BAS) in bipolar spectrum disorders. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:189–194. doi: 10.1177/0963721410370292. doi: 10.1177/0963721410370292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Flynn M, Liu RT, Grant DA, Jager-Hyman S, Whitehouse WG. Self-focused cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2009a;2(4):354–372. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.4.354. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.4.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Rose DT, Robinson MS, Kim RS, Lapkin JB. The Temple – Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression (CVD) Project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:403–418. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Raniere D, Dyller IM. Research methods in adult psychopathology. In: Kendall PC, Butcher JN, Holmbeck GN, editors. Handbook of research methods in clinical psychology. 2nd ed Wiley; New York: 1999. pp. 466–498. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Bender RE, Wagner CA. Longitudinal predictors of bipolar spectrum disorders: A behavioral approach system perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009c;16:206–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01160.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Grandin LD, Hughes ME, Hogan ME. Behavioral Approach System and Behavioral Inhibition System sensitivities: Prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10:310–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Smith J, Hughes M, Nusslock R. Behavioral Approach System (BAS) sensitivity and bipolar spectrum disorders: A retrospective and concurrent behavioral high-risk design. Motivation & Emotion. 2006b;30:143–155. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9003-3. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Gerstein RK, Keyser JD, Whitehouse WG, Harmon-Jones E. Behavioral Approach System (BAS)-relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009b;118(3):459–471. doi: 10.1037/a0016604. doi: 10.1037/a0016604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Keyser J, Gerstein RK. Adolescent-onset bipolar spectrum disorders: A cognitive vulnerability-stress perspective. In: Miklowitz DJ, Cicchetti D, editors. Understanding bipolar disorder: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. pp. 282–330. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, Rose DT. Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006a;115:145–156. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Bender RE, Whitehouse WG, Wagner CA, Liu RT, Grant DA, Harmon-Jones E. High Behavioral Approach System (BAS) sensitivity, reward responsiveness, and goal-striving predict first onset of bipolar spectrum disorders: A prospective behavioral high-risk design. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0025877. (in press) doi: 10.1037/a0025877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Urosevic S, Abramson LY, Jager-Hyman S, Nusslock R, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME. Progression along the bipolar spectrum: A longitudinal study of predictors of conversion from bipolar spectrum conditions to bipolar I and II disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):16–27. doi: 10.1037/a0023973. doi: 10.1037/a0023973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. The Altman self-rating mania scale. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42:948–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual. 4th Edition, Text Revision Author; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34-38 years. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;68:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00377-9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In: Clayton PJ, Barrett JE, editors. Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches. Raven Press; New York: 1983. pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Harper and Row; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, D’Afflitti JP, Quinlan DM. Experiences of depression in normal young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:383–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.383. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.85.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Zohar AH, Quinlan DM, Zuroff DC, Mongrain M. Subscales within the dependency factor of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;64:319–339. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6402_11. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6402_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke KC, Burke JD, Jr., Regier DA, Rae DS. Age at onset of selected mental disorders in five community populations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47(6):511–518. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Felton JW, Roberts JE. Testing the cognitive catalyst model of depression: Does rumination amplify the impact of cognitive diatheses in response to stress? Cognition and Emotion. 2011 doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.543330. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.543330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Rumination, negative cognition, and their interactive effects on depressed mood. Emotion. 2007;7(3):555–565. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.555. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell A, Alloy LB, Spasojevic J. Neediness and interpersonal life stress: Does congruence predict depression? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, O’Connor RM. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity model and child psychopathology: Laboratory and questionnaire assessment of the BAS and BIS. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:435–451. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030296.54122.b6. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000030296.54122.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Whiffen VE. Issues in personality as diathesis for depression: The case of sociotropy-dependency and autonomy-self-criticism. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118(3):358–378. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.358. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey RC, Gooding PA, Jones SH. Positive and negative cognitive style correlates of the vulnerability to hypomania. Journal of Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20789. (in press) doi: 10.1002/jclp.20789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Iacono WG. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Reviews in Psychology. 1989;40:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Krauss S, Spoont MR. A two-dimensional threshold model of seasonal bipolar affective disorder. In: Magnusson D, Ohman A, editors. Psychopathology: An interactional perspective. Academic Press; New York: 1987. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Beck AT. Cognitive schemas, beliefs, and assumptions. In: Dobson KS, Dozois DJA, editors. Risk factors in depression. Academic Press; San Diego: 2008. pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Development and validation of a scale for hypomanic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95(3):214–22. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.214. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.95.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD. The contribution of deficits in emotional clarity to stress responses and depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.004. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Biological variables in psychopathology: A psychobiological perspective. In: Sutker PB, Adams HE, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology. 2nd Edition Plenum Press; New York: 1993. pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Presidential Address, 1987. Psychophysiology and psychopathology: A motivational approach. Psychophysiology. 1988;25:373–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1988.tb01873.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1988.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-Raniere EL, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Depressive personality styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: prospective tests of the event congruency hypothesis. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8(4):382–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00337.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles DE, Rush AJ, Roffwarg HP. Sleep parameters in Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and unipolar Depressions. Biological Psychiatry. 1986;21:1340–1343. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90319-7. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Individual differences in emotional experience: Mapping available scales to processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:679–697. doi: 10.1177/0146167200268004. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH. Depression and general psychopathology in university students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93(1):19–30. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.1.19. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.93.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Neural systems, emotion and personality. In: Madden J, editor. Neurobiology of learning, emotion and affect. Raven Press; New York: 1991. pp. 273–306. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Eidelman P, Harvey AG. Transdiagnostic emotion regulation processes in bipolar disorder and insomnia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(9):1096–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.004. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Eidelman P, Johnson SL, Smith B, Harvey AG. Hooked on a feeling: Rumination about positive and negative emotion in inter-episode bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0023667. (in press) doi: 10.1037/a0023667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Howard GS. Self-report: Psychology’s four-letter word. American Journal of Psychology. 2010;133:181–188. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.123.2.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Allen JJB. Behavioral activation sensitivity and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: Covariation of putative indicators related to risk for mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:159–163. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE. Goals for research on bipolar disorder: The view from NIMH. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:436–441. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00894-5. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, Hirschfeld RM, Wang PS. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1561–1568. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL. Mania and dysregulation in goal pursuit: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:241–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Fingerhut R. Negative cognitions predict the course of bipolar depression, not mania. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2004;18:149–162. doi: 10.1891/jcop.18.2.149.65960. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Jones S. Cognitive correlates of mania risk: Are responses to success, positive moods, and manic symptoms distinct or overlapping? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(9):891–905. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20585. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, McKenzie G, McMurrich S. Ruminative responses to negative and positive affect among students diagnosed with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:702–713. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Alloy LB. The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):221–229. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.221. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambouropoulos N, Staiger PK. Reactivity to alcohol-related cues: Relationship among cue type, motivational processes, and personality. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:275–283. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.275. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LA, Cohen TR, Panter AT, Devellis BM, Yamanis TJ, Jordan JM, Devellis RF. Buffering against the emotional impact of pain: Mood clarity reduces depressive symptoms in older adults. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:975–987. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy N, Everitt B, Boydell J, Van Os J, Jones PB, Murray RM. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results from a 35-year study. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(6):855–863. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003307. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1079–1089. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. doi: 10.1017/S0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles R, Tai S, Christensen I, Bentall RP. Coping with depression and vulnerability to mania: A factor analytic study of the Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) Response Styles Questionnaire. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:99–112. doi: 10.1348/014466504X20062. doi: 10.1348/014466504X20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Cluss PA, Houck PR, Stapf DA. Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63:120–125. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid JR, Monroe SM, Roberts JR, Johnson SL, Garamoni GL, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Toward the standardization of life stress assessment: Definitional discrepancies and inconsistencies in methods. Stress Medicine. 1992;8:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Molz AR, Goldstein G. Mood disorders. In: Noggle C, Dean R, Horton AM Jr., editors. Encyclopedia of Neuropsychological Disorders. Springer Publishing Company; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow J, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of responses to depression on the remediation of depressive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:519–527. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.519. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson B. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Person perception and personality pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto JH, Lantermann ED. Individual differences in emotional clarity and complex problem solving. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 2006;25(1):3–25. doi: 10.2190/BUDG-Y02K-F254-YBGK. [Google Scholar]

- Rholes W, Riskind J, Neville B. The relationship of cognitions and hopelessness to depression and anxiety. Social Cognition. 1985;3(1):36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Riskind JH, Alloy LB. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders: Theory and research design/methodology. In: Alloy LB, Riskind JH, editors. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Erlbaum; New York: 2006. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Alloy LB. Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2003;27(3):275–292. doi: 10.1023/A:1023914416469. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfarb IS, Becker J, Khan A, Mintz J. Dependency and self-criticism in bipolar and unipolar depressed women. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;37(4):409–414. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude SS, Burnham BL. Connectedness and neediness: Factors of the DEQ and SAS subscales. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1995;19:323–340. doi: 10.1007/BF02230403. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the trait meta-mood scale. In: Pennebaker JW, editor. Emotional, Disclosure, and Health. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Stanton B, Garland A, Ferrier IN. Cognitive vulnerability in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30(2):467–72. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008879. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799008879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Gemar M, Williams S. Differential cognitive response to a mood challenge following successful cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy for unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:3–10. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.3. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic J, Alloy LB. Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion. 2001;1:25–37. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.25. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Shapero BG, Jager-Hyman S, Grant DA, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Behavioral Approach System (BAS)-relevant cognitive styles in individuals with high vs. moderate BAS sensitivity: A behavioral high-risk design. Cognitive Therapy and Research. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9443-x. (in press) doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Davidson RJ. Prefrontal brain asymmetry: A biological substrate of the behavioral approach and inhibition systems. Psychological Science. 1997;8:204–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00413.x. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Bentall RP. Hypomanic traits and response styles to depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:309–313. doi: 10.1348/014466502760379154. doi: 10.1348/014466502760379154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Knowles R, Tai S, Bentall RP. Response styles to depressed mood in bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;100:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.017. doi: 10.1348/014466502760379154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Avila C, Molto J, Caseras X. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:837–862. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00183-5. [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561. [Google Scholar]

- Urosevic S, Abramson LY, Harmon-Jones E, Donovan PM, Van Voorhis LL, Hogan ME, Alloy LB. The behavioral approach system (BAS) and bipolar spectrum disorders: Review of theory and evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1188–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.004. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Gucht E, Morriss R, Lancaster G, Kinderman P, Bentall RP. Psychological processes in bipolar affective disorder: negative cognitive style and reward processing. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194(2):146–51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047894. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S, Mehl MR. Knowing me, knowing you: The accuracy and unique predictive validity of self-ratings and other-ratings of daily behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;5:1202–1216. doi: 10.1037/a0013314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C, Abela JRZ, Brozina K. A comparison of stress measures in children and adolescents: A self-report checklist versus an objectively rated interview. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;28:251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(2):163–206. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman A, Beck AT. Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Nov, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg RE, Mohlman J. Individual differences in the acquisition of affectively valenced associations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1024–1040. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.1024. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Igreja I, Mongrain M. Dysfunctional attitudes, dependency, and self-criticism as predictors of depressive mood states: A 12-month longitudinal study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990a;14:315–326. doi: 10.1007/BF01183999. [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Moskowitz DS, Wielgus MS, Powers TA, Franko DL. Construct validation of the Dependency and Self-Criticism scales of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality. 1983;17:226–241. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(83)90033-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Quinlan DM, Blatt SJ. Psychometric properties of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990b;55:65–72. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674047. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5501&2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]