To the Editor: The sympathetic nervous system plays an important role in ventricular arrhythmogenesis. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) decreases the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias (VAs), and sudden cardiac death in patients with severe VAs 1,2 However, when LCSD is ineffective in suppressing VAs, adjunctive right cardiac sympathetic denervation (RCSD) may be an option. In humans, the safety and feasibility of BCSD in the management of VAs remains unclear. The present study was undertaken to assess the benefit of BCSD for the acute management of persistent VAs.

We reviewed the records of patients who underwent BCSD (or RCSD after prior LCSD failed to control arrhythmias). Review of patient data was in accordance with the guidelines of the institutional review board. These patients presented with electrical storm characterized by incessant ventricular tachycardia (VT), or repeated episodes of ventricular fibrillation (VF).

Five males and 1 female were included in the study. Mean age 60.1 years (47 to 75 years), mean LV EF 25.8% (15–40%) (Table). Five patients presented with monomorphic VT (MMVT), and 1 patient had polymorphic VT (PMVT). Of patients with MMVT, four had undergone previous endocardial VT ablation and one had undergone an epicardial VT ablation. The arrhythmia burden and number of therapies (automated or external defibrillator shocks, and anti-tachycardia pacing episodes) suffered by each patient is shown in the table.

Table.

Baseline characteristics, arrhythmia burden, clinical management, acute and intermediate outcomes are shown for patients in the study.

| Patient | Age/Gender | Substrate/ LV EF | VT Type | Anti-arrhythmics | GA /TEA | VT RFA | Arrhythmia Episodes / Arrhythmia Therapies* Pre-BCSD |

Arrhythmia Episodes / Arrhythmia Therapies* Post BCSD |

Response to BCSD | Survival to Discharge |

intermediate Follow up (Days post- Discharge) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 / M | Sarcoid / 20% | MMVT | Carvedilol Amiodarone |

No / No | 2 Endo | 45 / 30 (14 Days) | 3 / 2 (6 Days) | Partial | Yes | Death CHF (89 Days) |

| 2 | 66 / F | NICM / 20% | PMVT | Amiodarone Lidocaine Metoprolol |

Yes / Yes | n/a | 51 / 6 (13 Days) | 27 / 2 (8 Days) | Poor | No | n/a |

| 3 | 55 / M | NICM / 20% | MMVT | Amiodarone Carvedillol Lidocaine, Mexiletine |

No / No | 2 Endo 1 Epi |

39 / 17 (9 Days) | 0 / 0 (3 Days) | Complete | Yes | Alive (207 Days) |

| 4 | 47 / M | NICM / 15% | MMVT | Amiodarone Esmolol Diltiazem Carvedilol Verapamil Lidocaine Procainamide |

Yes / Yes | 3 Endo | 87 / 11 (28 Days) | 0 / 0 (7 Days) | Complete | Yes | Alive (153 Days) |

| 5 | 49 / M | NICM / 40% | MMVT | Amiodarone metoprolol |

No / No | 2 Endo | 43 / 25 (15 Days) | 0 / 0 (14 Days) | Complete | Yes | Alive (129 Days) |

| 6 | 75 / M | ARVC / 40% | MMVT | Amiodarone Metoprolol |

No / No | 2 Endo 1 Epi |

36 / 36 (14 Days) | 0 / 0 (14 Days) | Complete | Yes | Death Unknown Cause (21 Days) |

Therapies: Automated or Manual Defibrillation, and Anti-Tachycardia pacing.

ARVC – Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy, BCSD – Bilateral Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation, CHF – Congestive Heart Failure, Endo – Endocardial, Epi –Epicardial, GA – General Anesthesia, Ventricular Ejection Fraction, VT – Ventricular Tachycardia, NICM – Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy, TEA – Thoracic Epidural Anesthesia, MMVT – Monomorphic Ventricular tachycardia, PMVT –Polymorphic Therapies: Automated or Manual Defibrillation, and Anti-Tachycardia pacing. Anesthesia, M – Male, F – Female, LV EF – Left tachycardia, PMVT – Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

After presentation, VAs persisted despite intensive investigation and correction of all reversible causes. All patients received maximal tolerated β-blockade (metoprolol 50%, carvedilol 50%) and amiodarone. Lidocaine and/or mexiletine was utilized in 50% of the patients. Other antiarrhythmics were contraindicated or had failed previously. Of the five patients with MMVT, we performed catheter ablation in three, including one combined endocardial and epicardial approach. One patient underwent three endocardial ablations. In summary, all patients with MMVT underwent catheter ablation (mean 2.2±0.5 ablations/patient) either prior to or during the hospitalization where BCSD was performed. TEA was utilized in two patients, with little to no response noted, despite repositioning of the epidural catheter. The patients were all deemed poor transplant candidates. Only after these measures failed were patients considered for BCSD (or RCSD as an adjunct to prior LCSD).

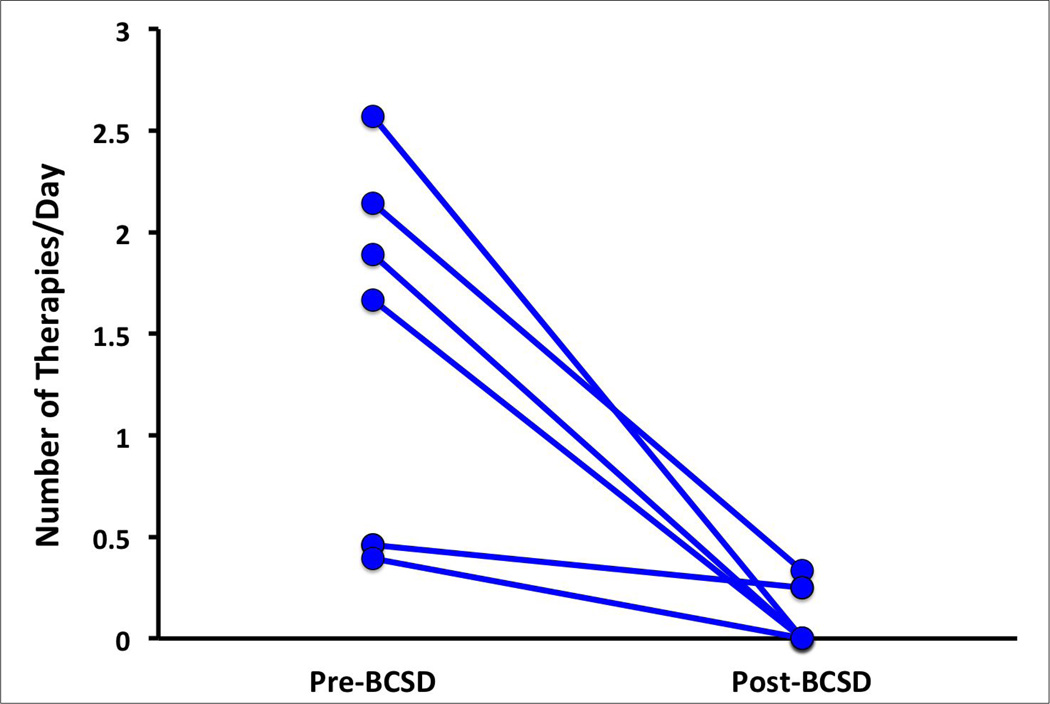

After BCSD, a complete response was observed in 66.7% of patients (4/6), while a partial response was seen in 16.7% of patients (1/6) and no response in 16.7% (1/6). ICD shocks and ATPs decreased to 0 shocks or ATPs in 3 patients, and decreased by greater than 50% in one patient (Figure, Table). External shocks decreased from 11 to 0 in another patient. Frequency of therapies before and after BCSD are shown in the Figure. Only one patient showed no response to BCSD. All five patients who showed a reduction in VAs to BCSD survived to discharge (Table), while the only non-responder expired after withdrawal of care, at the family’s request. After discharge, two deaths were noted (Table), neither of which were related to arrhythmias. Patient 1 continued to have heart failure exacerbations and elected to go on hospice care. Patient 6 expired at home for unknown reasons. Interrogation of his ICD showed no atrial or ventricular arrhythmias before or at the time of death.

Figure 1.

The acute improvement in therapies per day (number of therapies/number of days) before and after bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation are shown. Therapies included antitachycardia pacing episodes and automated or external defibrillation.

No significant electrocardiographic changes or events consistent with adrenergic insufficiency were documented in patients subsequent to bilateral denervation. Operative complications occurred in two patients (post-operative heart failure and poor tolerance of single lung ventilation during VATS).

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of BCSD reported to date. Limitations to this study include its small size, which precludes broad conclusions regarding the applicability of these results. Further, due to the lack of randomization and retrospective approach, biases which may have been involved in the decision making process cannot be excluded.

Mechanisms underlying the benefit of BCSD may include the interruption of adverse stellate ganglion remodeling, or mitigation of pro-arrhythmic neural signaling within the myocardium or stellate ganglia. Multiple lines of evidence suggest a potent anti-arrhythmic effect of BCSD on ventricular myocardium. In canine studies comparing left, right, or bilateral sympathectomy, the most profound anti-arrhythmic effects were seen with bilateral sympathectomy.3,4 Studies on spinal cord stimulation or thoracic epidural anesthesia2,5,6 all of which decrease global cardiac sympathetic activity have shown a profound protective effect. Compared to asystole and pulseless electrical activity, VT and VF are less frequent modes of SCD in patients after cardiac transplantation7, as these hearts are completely denervated,

Our study suggests that patients with incessant ventricular arrhythmias for whom no other therapeutic options exist, bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation may be beneficial. This procedure does not appear to result in adverse outcomes. Further studies examining the role of BCSD in suppressing human arrhythmias are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the NHLBI (R01HL084261) to KS Relationship with Industry: None

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nademanee K, Taylor R, Bailey WE, Rieders DE, Kosar EM. Treating electrical storm: sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy. Circulation. 2000;102:742–747. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourke T, Vaseghi M, Michowitz Y, Sankhla V, Shah M, Swapna N, et al. Neuraxial modulation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: value of thoracic epidural anesthesia and surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Circulation. 2010;121:2255–2262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.929703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks WW, Verrier RL, Lown B. Influence of vagal tone on sympathectomy-induced changes in ventricular electrical stability. Am J Physiol. 1978;234:H503–H507. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.5.H503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kliks BR, Burgess MJ, Abildskov JA. Influence of sympathetic tone on ventricular fibrillation threshold during experimental coronary occlusion. Am J Cardiol. 1975;36:45–49. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa ZF, Zhou X, Ujhelyi MR, et al. Thoracic spinal cord stimulation reduces the risk of ischemic ventricular arrhythmias in a postinfarction heart failure canine model. Circulation. 2005;111:3217–3220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahajan A, Moore J, Cesario DA, Shivkumar K. Use of thoracic epidural anesthesia for management of electrical storm: a case report. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1359–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaseghi M, Lellouche N, Ritter H, et al. Mode and mechanisms of death after orthotopic heart transplantation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]