Abstract

We have previously shown that retinoic acid (RA) has protective effects on high glucose (HG)-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of RA effects, we determined the interaction between nuclear factor (NF)-κB and RA signaling. HG induced a sustained phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and transcriptional activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes. Activated NF-κB signaling has an important role in HG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and gene expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). All-trans RA (ATRA) and LGD1069, through activation of RAR/RXR-mediated signaling, inhibited the HG-mediated effects in cardiomyocytes. The inhibitory effect of RA on NF-κB activation was mediated through inhibition of IKK/IκBα phosphorylation. ATRA and LGD1069 treatment promoted protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity, which was significantly suppressed by HG stimulation. The RA effects on IKK and IκBα were blocked by okadaic acid or silencing the expression of PP2Ac-subunit, indicating that the inhibitory effect of RA on NF-κB is regulated through activation of PP2A and subsequent dephosphorylation of IKK/IκBα. Moreover, ATRA and LGD1069 reversed the decreased PP2A activity and inhibited the activation of IKK/IκBα and gene expression of MCP-1, IL-6 and TNF-α in the hearts of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. In summary, our findings suggest that the suppressed activation of PP2A contributed to sustained activation of NF-κB in HG-stimulated cardiomyocytes; and that the protective effect of RA on hyperglycemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammatory responses is partially regulated through activation of PP2A and suppression of NF-κB-mediated signaling and downstream targets.

Keywords: High Glucose, Retinoic Acid, Cardiomyocytes, Apoptosis, NF-κB signaling

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic cardiomyopathy is one of the most prevalent cardiovascular complications of diabetes mellitus, which often occurs independently of coronary artery disease and hypertension (Battiprolu et al., 2010; Murarka and Movahed, 2010). Clinical and animal studies have shown that chronic hyperglycemia is a major initiating factor for diabetic cardiovascular complications (Cai et al., 2002; Schainberg et al., 2010). However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms associated with diabetic cardiomyopathy are incompletely understood. NF-κB is a transcription factor that directly regulates the expression of immediate-early response genes and genes involved in stress and inflammatory responses, following a variety of physiological or pathological stimuli, including cytokines, mitogens, viruses, and mechanical and oxidative stress (Wan and Lenardo, 2010). Inactive NF-κB is primarily located in the cytoplasm in association with the inhibitor of κB (IκB). Following exposure to various stimuli, IκB is phosphorylated by IκB kinases (IKKs) and degraded by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. The former allows NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus and bind to κB sequences, altering the expression of a diverse array of target genes (Baldwin, 2001). After activation, NF-κB binds to resynthesized IκB, leading to the termination of NF-κB-dependent transcription. This feedback loop is important in maintaining normal cellular responsiveness mediated by NF-κB. Dysregulated IKK or IκB may lead to persistent activation of NF-κB signaling. A large body of evidence suggests that NF-κB activation occurs in a sustained manner in diabetes, in association with elevated blood glucose levels and inflammation (Baker et al., 2011; Bierhaus et al., 2001; Granic et al., 2009; Hofmann et al., 1999). NF-κB signaling is also activated in high glucose (HG)-stimulated cardiomyocytes and diabetic hearts (Kuo et al., 2011; Mariappan et al., 2010). These studies suggest that chronic or sustained activation of NF-κB signaling may have an important role in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Thus, understanding the cellular mechanisms of hyperglycemia-induced persistent activation of NF-κB signaling, has important clinical relevance in developing alternative therapeutic targets in the treatment of diabetic cardiomyopathy.

ATRA, the active metabolite of vitamin A, exerts a number of biological activities, including regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis and developmental changes. The cellular function of ATRA is mediated through retinoic acid receptors (RARα, β and γ) and retinoid X receptors (RXRα, β and γ). These receptors form RXR/RXR homodimers and RXR/RAR heterodimers, and directly activate gene transcription, by binding to specific retinoic acid response elements in target gene promoter regions. Recently, we have reported that RA-stimulated RAR/RXR signaling is impaired by HG (Singh et al., 2011), and that downregulated RAR/RXR signaling contributes to HG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Activation of RAR/RXR signaling prevented HG-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis, in both neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes (Guleria et al., 2011). Though our studies indicated that RAR/RXR mediated signaling has an important role in diabetes induced cardiac remodeling, the underlying molecular signaling mechanisms remain unclear. It has been shown that NF-κB activity is significantly increased in vitamin A deficient mice and that ATRA attenuates the increased activation of NF-κB (Austenaa et al., 2004; Datta and Lianos, 1999). These results suggest an interaction between RAR/RXR and NF-κB signaling. We hypothesize that impaired RA signaling is associated with HG-induced activation of NF-κB, through regulation of its upstream modulator; and that RA-mediated protective effects on cardiomyocytes are (at least partially) through regulation of NF-κB signaling. Our data showed that sustained activation of NF-κB has an important role in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammatory responses in response to HG stimulation, and that HG-induced reduction of PP2A activity contributed to sustained activation of NF-κB. RAR and RXR ligands suppressed HG-induced transcriptional activation of NF-κB signaling, through activation of PP2A and subsequent dephosphorylation of IKK and IκBα, in cultured cardiomyocytes, and in hearts of ZDF rats, in vivo. Our data provide substantive evidence that the interaction between RAR/RXR and NF-κB signaling, may serve as a mechanism that is associated with hyperglycemia-induced cardiac remodeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Reagents

Cell culture medium, antibiotics and fetal bovine serum were obtained from Invitrogen (Baltimore, MD). Anti-p-PP2Ac, -IκBα, -p65 NF-κB and -histone antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), anti-actin antibody and other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). LGD1069 (RXR selective agonist) was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). DOSPER [1, 3-dioleoyloxy-2-(6-carboxyspermly)-propyl amide] was from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). JSH-23 was purchased from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ). Phospho-IKKα/β, phospho-IκBα antibodies, anti-IKKβ and anti-PP2Ac antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA).

Rat cardiomyocyte culture

Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Texas A&M Health Science Center and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, 1996). Primary cultures of neonatal cardiomyocytes were prepared from the ventricles of 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups, as previously described (Palm-Leis et al., 2004).

Animal groups

Male Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats and age matched lean Zucker rats (Charles River Laboratories) were used. All animals were randomized into 6 groups (6 rats/group) at the age of 9 weeks: (1) control lean rats; (2) Lean rats treated with ATRA (10 mg/kg body weight/day); (3) Lean rats treated with LGD1069 (20 mg/kg body weight/day); (4) control ZDF rats; (5) ZDF+ATRA; and (6) ZDF + LGD1069. Rats were given vehicle (corn oil), ATRA or LGD1069 daily, orally by gastric gavage. All rats had free access to rat chow (Purina 5008, Charles River Laboratories) and water. Before sacrificing, fasting blood glucose was measured using a commercially available glucometer (Elite’ Bayer, Newbury, U.K.). Rats were sacrificed after 2 weeks of treatment (at the age of 11 weeks) and hearts arrested in Krebs-Henselite solution and immediately placed into liquid nitrogen.

Agarose gel electrophoresis for DNA fragmentation

Cardiomyocyte apoptosis was determined by DNA fragmentation. At the conclusion of each treatment, cardiomyocytes were harvested and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 10 mM EDTA; and 0.5% Triton X-100), followed by incubation with 40 µg of RNase, for 1 h, at 37°C and fragmented DNA extracted. The fragmented DNA was electrophoretically fractionated on a 1.5% Agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide, as described previously (Choudhary et al., 2008a).

Nuclear translocation of NF-κB

Nuclear and cytosolic proteins were extracted from cardiomyocytes or left ventricles, using NE-PER reagents (Thermo Scientific). The purity of nuclear protein extraction was determined before performing experiments (Guleria et al., 2011). The expression of NF-κB in the cytosol and nuclear fractions was determined using anti-NF-κB (p65) antibody, by Western blotting. Blots were reprobed with anti-actin (cytosol extraction) or anti-histone (nuclear extraction) antibody, respectively, to verify equal loading.

Immunocytochemistry

Cardiomyocytes were fixed in 100% methanol, at −10 °C, for 5 min and washed with cold PBS buffer. Cells were first incubated with antibody against NF-κB p65 (1:25) and then with anti-FITC antibody (1:25, green), to determine the localization of NF-κB. Myocyte nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Immunostained cardiomyocytes were visualized under a fluorescence microscope coupled with an image analysis system.

Western blot analysis

Cardiomyocytes were lysed in buffer, as previously described (Palm-Leis et al., 2004). Equal amounts of total extracted proteins (50 µg) were separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with primary antibodies. Binding of primary antibody was detected with horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated, goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The phosphorylation of IKK, IκBα and PP2Ac was detected using specific anti-phospho-IKKα/β (serine), -IκBα (serine), and -PP2Ac (tyrosine) antibodies, respectively. These blots were reprobed with anti-IKKβ, -IκBα, and -PP2Ac antibodies to detect total protein expression of IKKβ, IκBα and PP2Ac. The blots were then reprobed with anti-actin antibody to verify equal loading between samples. The expression of Bcl-2 and Bax was determined using corresponding antibodies and reprobed with actin to verify equal loading.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

The effect of HG on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, in cardiomyocytes, was determined by transfection using the NF-κB luciferase reporter vector, pNF-κB-Luc (Panomics, Santa Clara, CA). Transfection with pNF-κB-Luc and control reporter vector was performed using DOSPER Liposomal transfection reagents, as described previously (Guleria et al., 2011). After experimental treatments, cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed in passive lysis buffer (1X) provided in the dual luciferase kit (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA) and assayed for luciferase activity, using the LB96V MicroLumat Plus luminometer (EG & G Berthold, TN), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All transfections were performed in triplicate. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection of cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes were transfected with 50 nM of PP2Ac siRNA oligoribonucleotides (Invitrogen), using 3 µg/ ml DOSPER for 12 h, in OPTI-MEM I medium (Gibco, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Scrambled probe was used as a negative control. After washing, cells were maintained in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. PP2Ac siRNA (Dharmacon SMARTpool) was obtained from Thermo Scientific (Lafayette, CO).

Transfection

The replication-defective adenovirus-encoding dominant negative IκBα S32A (AdIκBα, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) and control virus (AdLacZ) were plaque purified, and amplified using HEK293 cells. The multiplicity of viral infection (MOI) for each virus was determined by dilution assay in HEK293 cells. Cardiomyocytes were infected with AdIκBα or AdLacZ at a MOI of 10–50 plaque-forming units for 8 h, at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM medium for further treatment or analysis.

Real time RT-PCR

Gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 was determined by real time RT-PCR, using the TaqManR Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX). PCR was performed using the Mx3005P Real-time PCR System (Stratagene, Wilmington, DE). The relative amount of mRNAs was calculated using the comparative CT method. GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control for all experiments (Choudhary et al., 2008b).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between experimental groups was determined using one-way ANOVA, combined with the Tukey-Kramer Multiple Comparisons test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

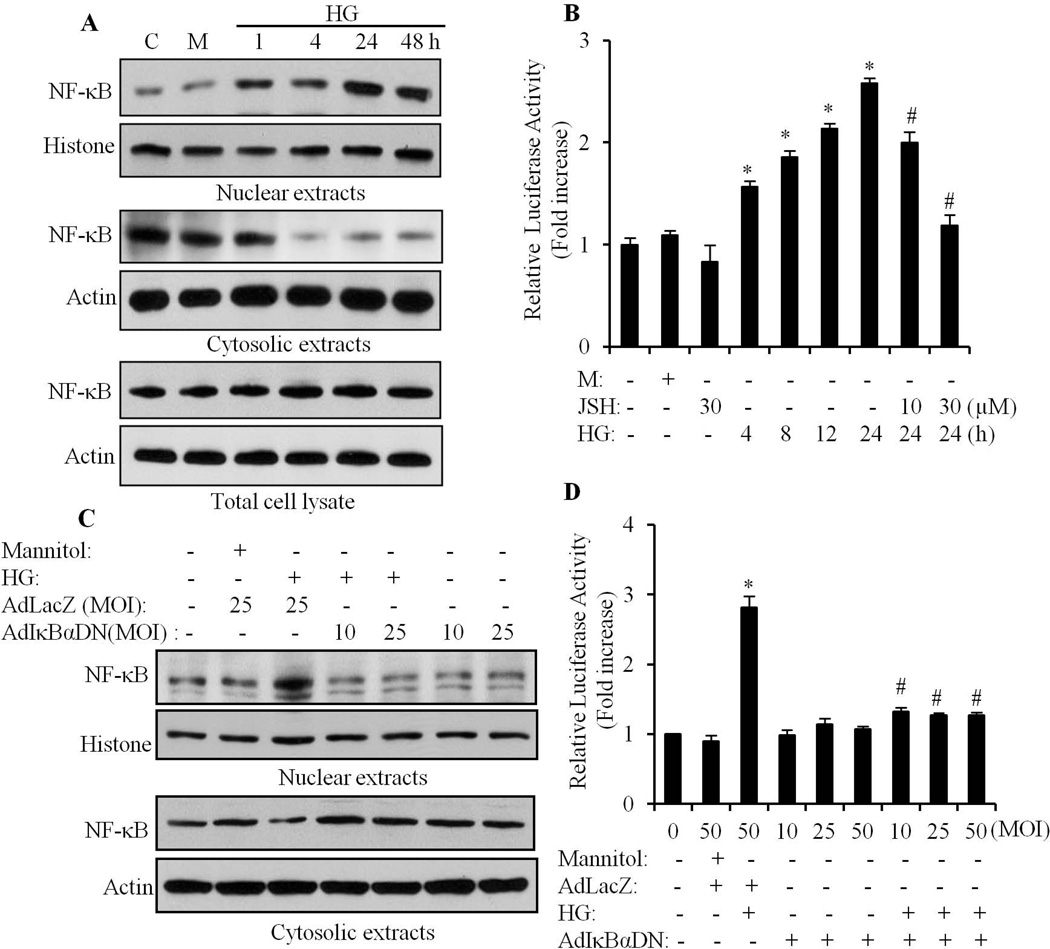

High glucose induces activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes

To determine the effect of HG on NF-κB activation, neonatal primary cultured cardiomyocytes were exposed to HG (25 mM) for different time periods, and nuclear translocation of NF-κB analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig 1A, mostly the inactive form of NF-κB (p65) was present in the cytosol of cardiomyocytes that were exposed to normal glucose and mannitol. Nuclear translocation of NF-κB was observed after 1 h of HG stimulation; and the maximum nuclear translocation was observed from 24 to 48 h of HG stimulation. The protein level of NF-κB in total cell lysate was not affected by HG. Next, we determined the effect of HG on NF-κB promoter activity. Cardiomyocytes were transfected with a construct containing the NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporter gene (NF-κB-Luc) and luciferase activity determined at different time points (Fig. 1B). The luciferase activity increased after 4 h of HG stimulation and peaked at 24 h (2.5 fold, compared to control). The increased NF-κB promoter activity was dose dependently inhibited by JSH-23 (a cell-permeable diamino compound that selectively blocks nuclear translocation of p65 NF-κB, without affecting IκB degradation). To further confirm the HG effect on NF-κB, cardiomyocytes were infected with adenovirus-mediated dominant negative IκBα S32A (AdIκBαDN). The phosphorylation-defective IκBα acts by sequestering the cytoplasmic NF-κB pool in a manner that is insensitive to extracellular stimuli. As shown in Fig. 1C and D, HG-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB and increased NF-κB promoter activity was completely blocked by AdIκBαDN. These data suggest that HG induced a sustained activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes, rather than an acute response (within minutes to hours).

Fig. 1. High glucose induces activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes.

A. Neonatal cultured cardiomyocytes were exposed to high glucose (HG) for different time periods, and whole cell lysate, nuclear and cytosolic proteins were extracted separately, and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB determined by Western blotting, using anti-p65 antibody. Mannitol (M, 19.5mM) was used as an osmolarity control. Equal loading was assessed with an anti-histone and anti-actin antibody, respectively. B. Cardiomyocytes were exposed to HG for 4–24 h, in the presence or absence of JSH-23, and the NF-κB luciferase reporter assay performed, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG (24 h). C. Cardiomyocytes were infected with AdIκBαDN or AdLacZ, and exposed to HG for 24 h, and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB was determined. D. After infection with AdIκBαDN or AdLacZ, HG-induced NF-κB promoter activity was analyzed. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG.

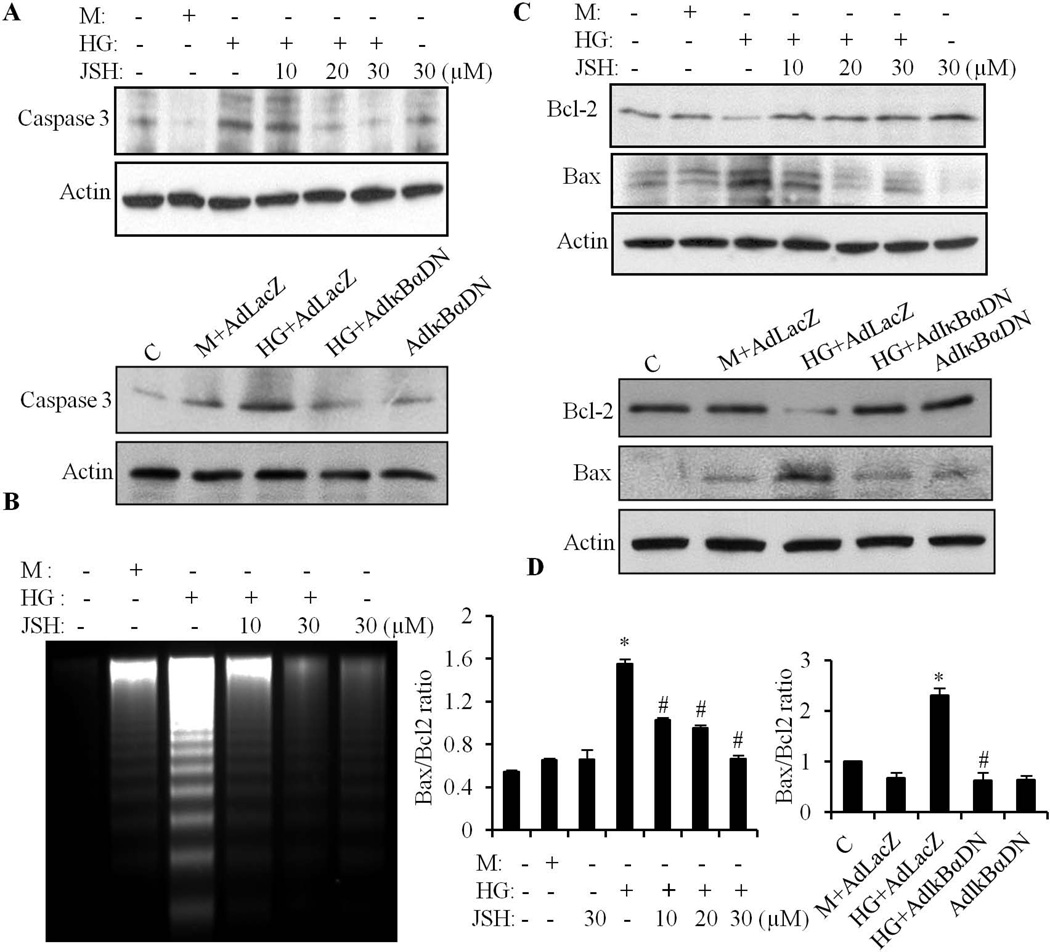

NF-κB signaling is involved in high glucose-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis

We have previously demonstrated that HG induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes (Guleria et al., 2011). Here, we further determined whether NF-κB signaling was involved in the HG effects. Cardiomyocytes exposed to HG for 24 h, showed a prominent DNA ladder, characteristic of cell apoptosis (Fig. 2B). DNA ladder formation was significantly inhibited by JSH-23 pretreatment. JSH-23 or mannitol alone had no effect. Myocardial caspase-3 activation is a final common point in caspase-dependent apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 2A, the intensity of the cleaved caspase-3 increased significantly following HG exposure. Pretreatment with JSH-23 or overexpression of AdIκBαDN inhibited the cleaved caspase-3 expression. The ratio between Bax and Bcl-2 expression has been proposed as an important marker of myocardial cell survival. Western blot analyses showed a relative decrease in Bcl-2 and an increase in Bax expression in HG-stimulated cells (Fig. 2C), resulting in a significantly increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (Fig. 2D). Inhibition of NF-κB by JSH-23 or overexpression of AdIκBαDN restored the decreased expression of Bcl-2 and prevented the HG-induced increase in Bax expression, thereby restoring the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio to control levels (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that NF-κB mediated pro-apoptotic signaling has an important role in HG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

Fig. 2. HG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis is regulated through NF-κB signaling.

A. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with 10–30 µM of JSH-23 or infected with 10 MOI of AdLacZ and AdIκBαDN, and exposed to HG for 24 h. The levels of cleaved (active) caspase-3 were determined by Western blot. B. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with or without JSH-23 for 30 min, and exposed to HG for 24 h. Mannitol (M) was used as an osmolarity control. Cells were harvested and fragmented DNA isolated and separated by electrophoresis. C. Following the same treatment procedures as (A), the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax was determined. Blots were reprobed using anti-actin antibody, to verify equal loading. D. The intensity of the bands was analyzed by densitometry and the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio calculated. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG or HG+LacZ.

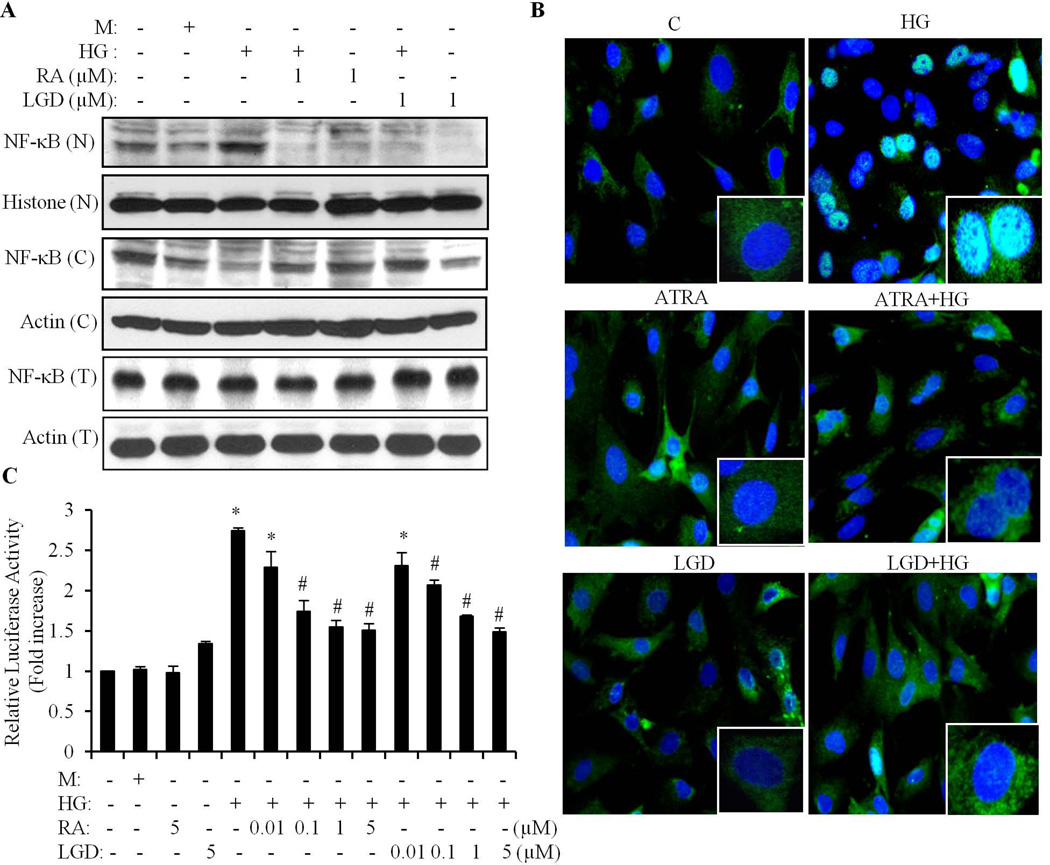

Activation of RAR and RXR inhibits HG-induced NF-κB activation in cardiomyocytes

HG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis was prevented by RA, through inhibition of oxidative stress (Guleria et al., 2011). It is known that reactive oxygen species activate multiple transcription factors, including NF-κB (Morgan and Liu, 2011). Thus, we determined whether the protective effect of RA was mediated through NF-κB signaling. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with 1µM of ATRA (pan-RAR ligand) or LGD1069 (RXR ligand) for 2 h, and exposed to HG for another 24 h. As shown in Fig. 3A & B, HG induced a significant amount of NF-κB that translocated from cytosol to the nucleus, and which was inhibited by ATRA and LGD1069. ATRA and LGD1069 alone had no effect. HG-induced increases in NF-κB luciferase activity were dose-dependently inhibited by ATRA and LGD1069 (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that activation of both RAR and RXR inhibits HG-induced nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation of NF-κB, by suppressing signaling that leads to the activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 3. Activation of RAR and RXR signaling inhibits HG-induced activation of NF-κB.

A. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with or without 1µM of ATRA (RA) or LGD1069 (LGD) for 2 h, and exposed to HG for an additional 24 h. Mannitol (M) was used as an osmolarity control. Whole cell lysate (T), cytosolic (C) and nuclear (N) proteins were extracted and expression of NF-κB determined. Blots were reprobed using anti-actin and anti-histone antibodies to verify equal loading, respectively. B. Following the same treatment procedures as (A), the localization of NF-κB was determined by immunofluorescense staining, using anti-p65 NF-κB antibody (green). Cardiomyocyte nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Results shown are merged pictures, representative of three separate experiments. C. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with or without different doses of ATRA (RA) or LGD1069 (LGD) for 2 h, exposed to HG for an additional 24 h, and an NF-κB luciferase reporter assay performed. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG.

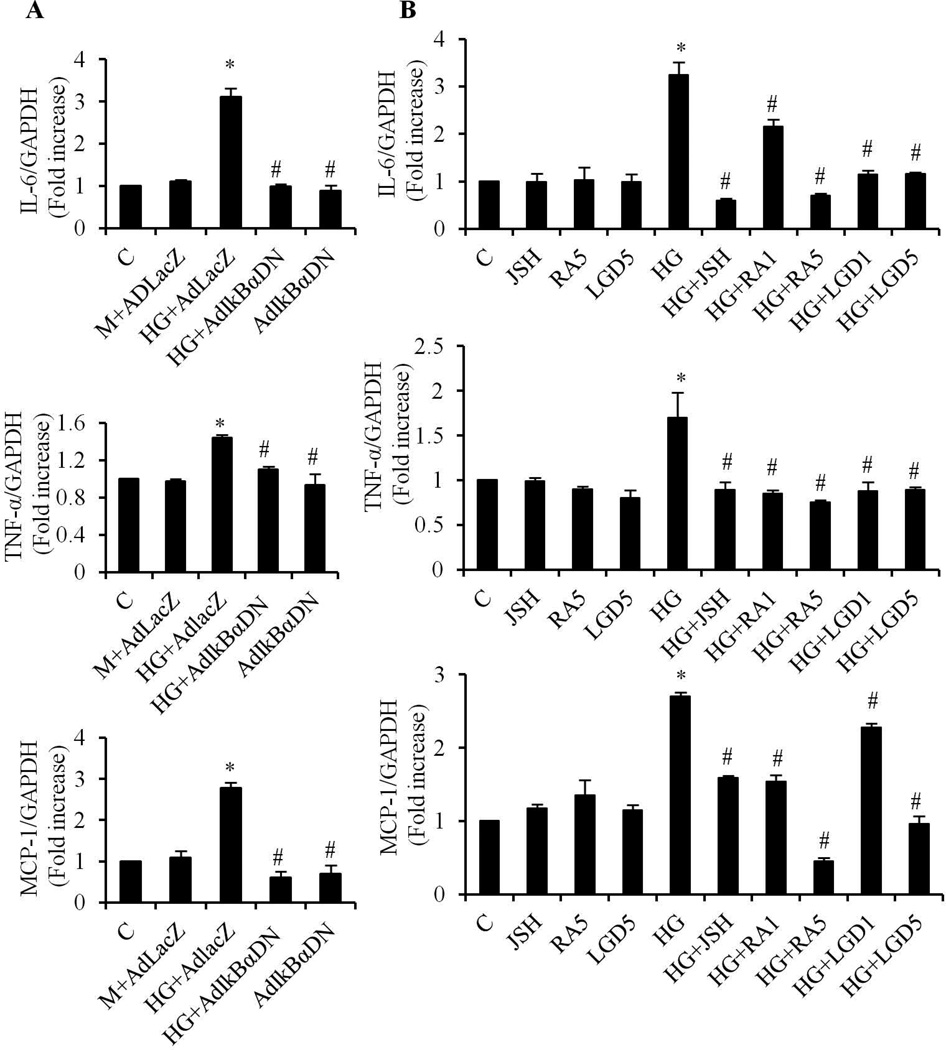

Effect of RA on NF-κB-mediated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines

Diabetic cardiomyopathy is associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) (Drimal et al., 2008; Younce et al., 2010). These cytokines are under the transcriptional control of NF-κB (Libermann and Baltimore, 1990; Patel and Santani, 2009). To further confirm whether NF-κB signaling is involved in the protective effect of RA, we determined the effect of RA on the gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1. HG induced significant increases in gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1, which were suppressed by JSH-23 (Fig. 4B) or overexpression of AdIκBαDN (Fig. 4A), indicating that NF-κB modulates the gene expression of these cytokines. The increased gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 was completely prevented by ATRA and LGD1069, at 5 µM; and partially inhibited at 1 µM (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that activation of RAR and RXR signaling inhibits NF-κB-mediated cytokine expression and inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 4. RA inhibits HG-induced gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Cardiomyocytes were infected with 10 MOI of AdIκBαDN, AdLacZ (A), or pretreated with or without 1 and 5 µM of ATRA (RA1, RA5), LGD1069 (LGD1, LGD5) or 30 µM of JSH-23 (JSH) (B), and exposed to HG for 24 h. Gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 was determined by real-time RT-PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH. Data (mean ± SEM, n=3) are expressed as a relative value compared to control. *, p<0.05, vs control; #, p<0.05, vs HG or HG + AdLacZ.

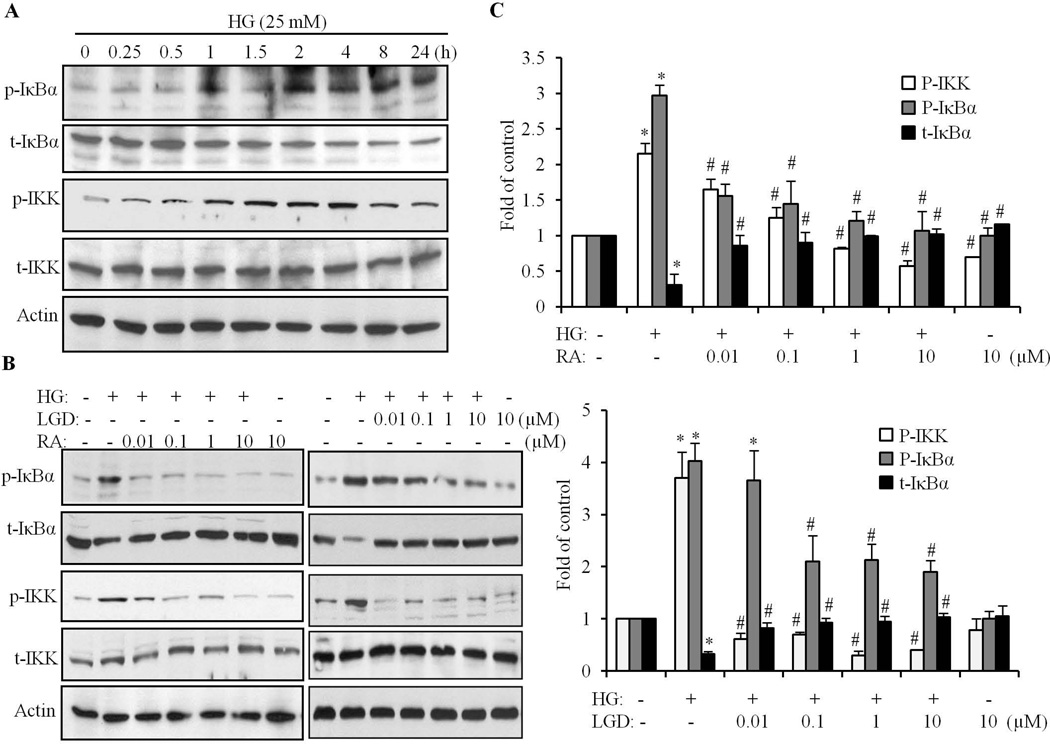

Activation of RAR and RXR inhibits HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα

The signaling events that lead to NF-κB activation, involve phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteolytic degradation of IκB in the cytosol, followed by translocation of the active dimer (p65/p50) to the nucleus, where it binds to cognate DNA sequences to activate transcription (Barnes and Karin, 1997). Phosphorylation of IκB is mediated by the protein kinases, IκB kinase (IKKα and IKKβ) (Karin and Ben-Neriah, 2000). To determine the mechanisms whereby RA inhibits transcriptional activation of NF-κB, we first examined whether the extent of IKK and IκBα phosphorylation is altered after HG exposure in cardiomyocytes. HG induced an increase in IκBα phosphorylation from 1 to 1.5 h, whereas a marked increase was observed at 2 h, and phosphorylation was maintained at a high level for up to 24 h (Fig. 5A). In parallel, the total amount of IκBα protein was decreased after exposure to HG for 1 h, and a dramatic decrease was observed following 2 h of HG exposure, which was maintained at low levels at 24 h (Fig. 5A); whereas, no changes were observed in the total actin level. These data indicated that sustained phosphorylation of IκBα resulted in continuous IκBα degradation. An increased phosphorylation of IKK was observed at 30 min and peaked at 2 – 4 h following HG exposure, and was maintained at a high level at 24h. These data suggest that the activation of IKK/IκBα by HG is persistent in cardiomyocytes. Next, we determined the effect of RA on phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα. As shown in Fig. 5B & C, HG induced phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα was dose dependently inhibited by ATRA and LGD1069. Furthermore, ATRA and LGD1069 restored the expression of IκBα to a normal level in HG-stimulated cardiomyocytes. These results indicate that the inhibitory effect of RA on NF-κB activation was mediated through regulation of phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and subsequent degradation of IκBα in cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 5. RA inhibits HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα.

A. Cardiomyocytes were exposed to HG for different time periods (0–24 h), and phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα determined by Western blot, using specific anti-phospho-IKKα/β and anti-phospho-IκBα antibody, respectively. Blots were reprobed with anti-IKK and anti-IκBα antibodies, to determine the expression of IKK and IκBα, respectively. Equal loading was assessed using an anti-actin antibody. B. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with different doses (0.01–10 µM) of ATRA (RA) or LGD1069 (LGD) for 2 h, and exposed to HG for an additional 4 h, and the phosphorylation and expression of IKK and IκBα determined. C. Densitometric quantification of p-IKK, p-IκBα and total IκBα protein bands, normalized to actin. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG.

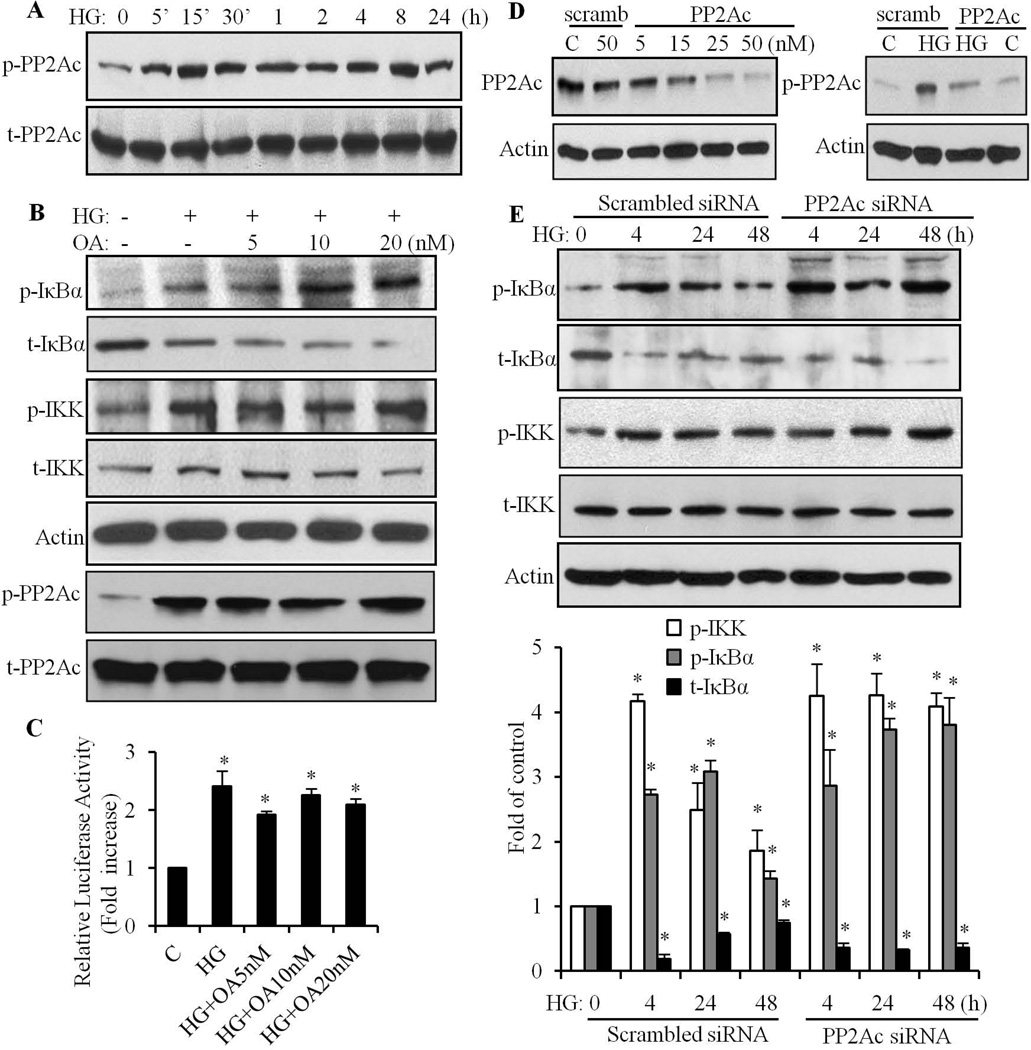

Role of protein phosphatase 2A in HG-induced sustained phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα in cardiomyocytes

We observed that HG-induced sustained phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and degradation of IκBα in cardiomyocytes, which was different than the activation pattern in response to inflammatory and other stressful stimuli (minutes to hours) (Anest et al., 2003; Chandrasekar et al., 2001). To elucidate the mechanisms of the HG mediated effects, we determined the role of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) in regulation of IKK and IκBα in cardiomyocytes. An active PP2A enzyme consists of a heterotrimer of the structural A subunit, a catalytic C subunit, and a regulatory B subunit. PP2A activity can be modulated by the tyrosine phosphorylation state of PP2Ac (PP2A C subunit), since the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in PP2Ac represents decreased phosphatase activity (Chen et al., 1992; Chen et al., 1994). Thus, we determined PP2A activity by analyzing the level of tyrosine phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 6A, PP2Ac was rapidly phosphorylated at 5 min of HG stimulation and the tyrosine phosphorylation was maintained at a high level up to 24 h, indicating that PP2A activity was continuously suppressed by HG, in cardiomyocytes. To determine the role of PP2A in HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα, okadaic acid (OA), a selective inhibitor of PP2A at a low concentration (1–10 nM), was used (Cohen et al., 1990). The tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac was maintained at a high level following okadaic acid treatment (Fig. 6B). HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK, IκBα and the degradation of IκBα was further promoted by okadaic acid (Fig. 6B). The HG-induced increase in promoter activity of NF-κB was also maintained at a comparable level with okadaic acid treatment (Fig. 6C). To provide additional confirmation that HG-induced sustained activation of NF-κB signaling was mediated by PP2A, the expression of PP2Ac was silenced by transfecting cells with PP2Ac siRNA. As shown in Fig. 6D, the expression of PP2Ac was significantly reduced (90–95%) following transfection of PP2Ac siRNA in cardiomyocytes (left panel). Silencing the expression of PP2Ac also attenuated HG-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac (right panel). HG exposure for 4–48 h, induced a sustained phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα, along with a markedly decreased expression of IκBα (Fig. 6E), further confirming the results shown in Fig. 5A, that HG induced a sustained activation of NF-κB signaling in cardiomyocytes. Following transfection with PP2Ac siRNA, the HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and degradation of IκBα was further intensified and sustained after 48 h of HG stimulation. These results suggest that PP2A negatively regulates HG-induced activation of NF-κB signaling, and that HG-induced inhibition of PP2A activity may serve as a key mechanism leading to the sustained phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and activation of NF-κB in cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 6. Role of PP2A in HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα.

A. Cardiomyocytes were exposed to HG for different time periods (0–24 h), and tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac determined, using specific anti-phospho-PP2Ac antibody. Equal loading was determined using anti-PP2Ac antibody. B. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with okadaic acid (OA, 5–20 nM) for 1 h, exposed to HG for an additional 4 h, and phosphorylation and expression of IKK, IκBα and PP2Ac determined. Equal loading was assessed using an anti-actin antibody. C. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with okadaic acid (OA, 5, 10 and 20 nM) for 1 h, exposed to HG for an additional 24 h, and NF-κB luciferase activity was determined. *, p<0.05 vs control. D. The expression of PP2Ac was silenced by transfecting cardiomyocytes with PP2Ac siRNA. The expression of PP2Ac (left panel) and phosphorylation of PP2Ac (right panel) was determined. Blots were reprobed with anti-actin antibody to verify equal loading. E. Cardiomyocytes were exposed to HG for different time periods, with or without silencing the expression of PP2Ac, and phosphorylation and expression of IKK and IκBα determined and quantified. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs control.

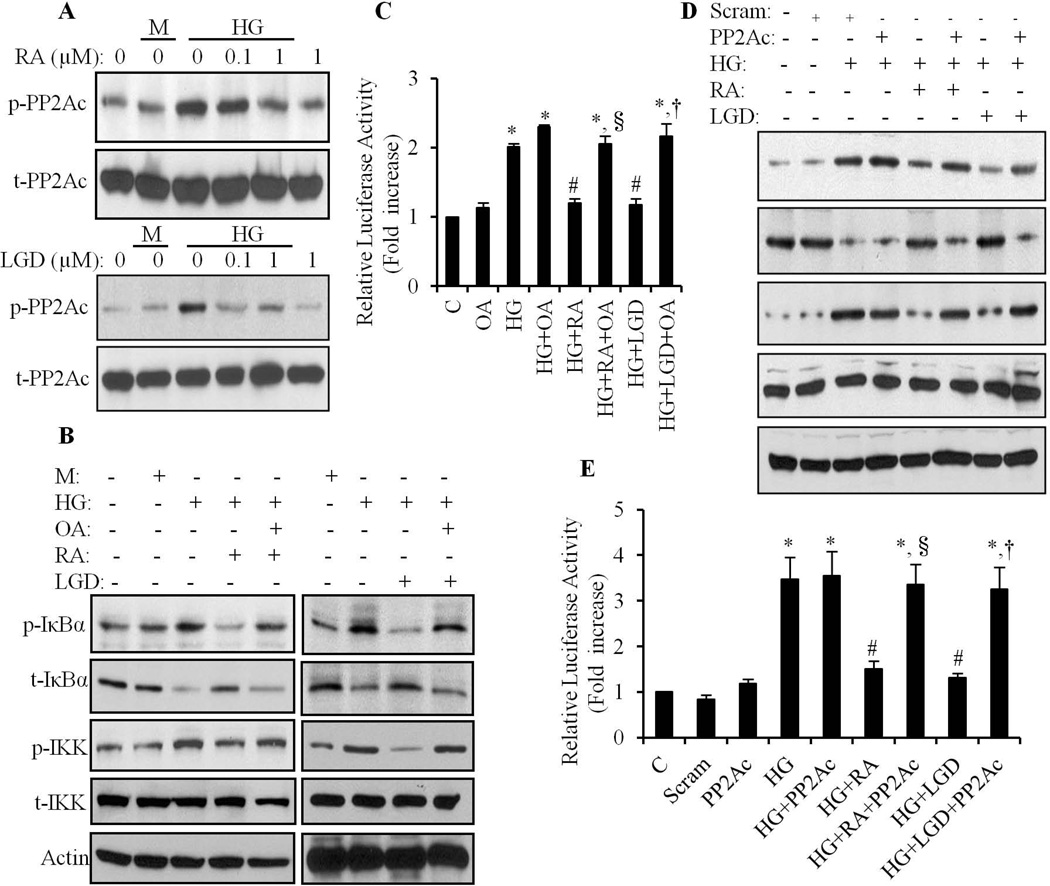

Role of PP2A in the RA-mediated inhibitory effects on IKK and IκBα

It has been shown that expression and activation of PP2A is increased by RA in cancer cell lines (Purev et al., 2011; Ramirez et al., 2005). Thus, we hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of RA on NF-κB signaling was mediated through PP2A. As shown in Fig. 7A, HG-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac was significantly inhibited by ATRA and LGD1069, indicating that the HG suppressed PP2A activity was restored. We further demonstrated that inhibition of PP2A activity by OA (10 nM), abolished the inhibitory effect of ATRA and LGD1069 on HG-induced phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα, degradation of IκBα (Fig. 7B) and transcriptional activation of NF-κB (Fig. 7C). Silencing the expression of PP2Ac, resulted in similar results as observed with OA treatment (Fig. 7D & E). These data suggest that PP2A was specifically responsible for the inhibitory effect of RA on NF-κB signaling.

Fig. 7. Role of PP2A in the RA-mediated inhibitory effect on IKK and IκBα.

A. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with 0.1–1 µM of ATRA (RA) or LGD1069 (LGD), exposed to HG for an additional 1 h, and the tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac determined. Mannitol (M) was used as an osmolarity control. B. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with 10 nM of okadaic acid for 1 h, treated with 1 µM of ATRA (RA) or LGD1069 (LGD) for 2h, and then exposed to HG for an additional 4 h. The phosphorylation and expression of IKK and IκBα was determined. Equal loading was determined using anti-actin antibody. C. After pretreatment with okadaic acid, ATRA and LGD1069, as noted in B, cardiomyocytes were exposed to HG for 24 h, and NF-κB Luciferase promoter activity determined. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG; §, p<0.05 vs HG+RA, †, p<0.05 vs HG+LGD. D & E. Scrambled (Scram) or PP2Ac siRNA (PP2Ac) transfected cardiomyocytes were pretreated with 1µm of ATRA (RA) or LGD1069 (LGD), and exposed to HG for an additional 4 h (D) and 24 h (E), and phosphorylation and expression of IKK and IκBα (D) and NF-κB promoter activity (E) determined. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs HG; §, p<0.05 vs HG+RA, †, p<0.05 vs HG+LGD.

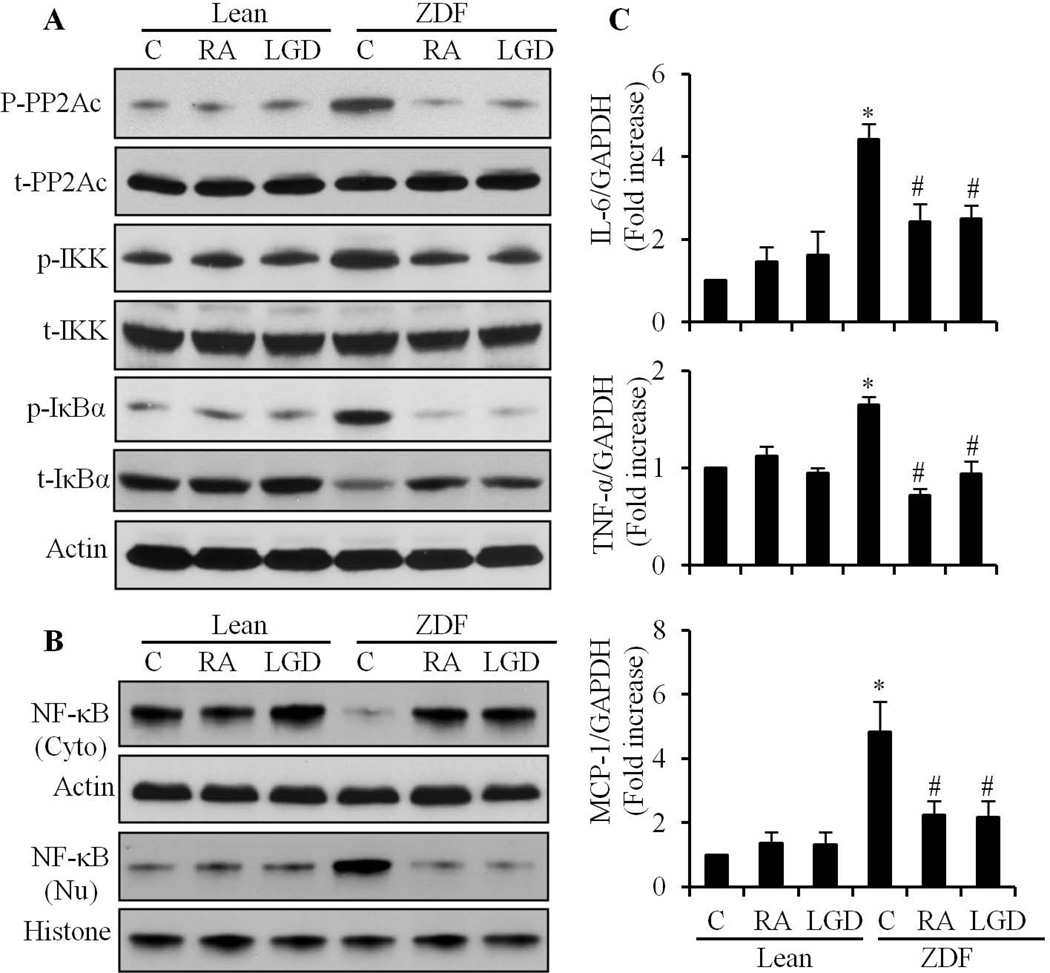

Activation of NF-κB signaling in diabetic hearts

To confirm our in vitro findings, we determined the role of RA in the regulation of NF-κB signaling in hearts from ZDF rats. At 11 weeks of age, ZDF rats were hyperglycemic (blood glucose: 528 ± 28 mg/dl), compared with lean rats (85 ± 1.7 mg/dl). Two weeks of ATRA and LGD1069 treatment, significantly reduced the increased blood glucose level in ZDF rats (223 ± 25 mg/dl and 260 ± 12 mg/dl, respectively; p<0.001 vs ZDF group), suggesting that activation of RAR/RXR-mediated signaling has anti-diabetic effects. A significantly increased phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα was observed in ZDF rat hearts (Fig. 8A), which was accompanied by decreased protein expression of IκBα. Nuclear translocation of NF-κB was also observed in the heart of ZDF rats (Fig. 8B). The phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα, degradation of IκBα and nuclear translocation of NF-κB was inhibited by ATRA or LGD1069. Moreover, a dramatic increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac was observed in ZDF rat hearts, which was also prevented by ATRA or LGD1069 (Fig. 8A). We further observed a significantly increased gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1, in ZDF rat hearts, which was suppressed by ATRA or LGD1069 (Fig. 8C). These results suggested that NF-κB signaling is activated continuously in diabetic heart, and that decreased PP2A activity likely contributes to this effect. Activation of RAR/RXR-mediated signaling, inhibited diabetes-induced inflammatory responses through regulation of PP2A activation and subsequent NF-κB activation in diabetic hearts.

Fig. 8. Effect of LGD1069 on NF-κB signaling in diabetic hearts from ZDF rats.

A. Lean and ZDF rats, treated with or without ATRA (RA) orLGD1069 (LGD) for 2 weeks. Left ventricles were isolated and myocardium lysates prepared. Phosphorylation and expression of IKK, IκBα and PP2Ac were determined by Western blot. B. Cytosol and nuclear protein was prepared from left ventricles and the expression of NF-κB in cytosol (Cyto) and nuclear (Nu) fractions was determined by Western blot. Equal loading was verified by actin (cytosol) and histone (nuclear). C. Total RNA was isolated from left ventricles and gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 determined by real-time RT-PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH. Data (mean± SEM, n=6) are expressed as a relative value, compared to Lean control. *, p<0.05, vs Lean; #, p<0.05, vs ZDF.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that RA protects cardiomyocytes from HG-induced apoptosis, by reducing HG stimulated oxidative stress and upregulation of renin-angiotensin system components (Guleria et al., 2011). However, the signaling mechanisms whereby RA protects cardiomyocytes from HG-mediated cellular injury remained unclear. The present study provides substantive evidence supporting the concept that inhibition of HG-induced activation of NF-κB signaling has an important role in RA-mediated cardio-protective effects. PP2A, which serves as a key modulator, is involved in RA-mediated inhibitory effects on HG-induced activation of NF-κB and NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes and diabetic hearts. This study also demonstrated that HG-induced reduction of PP2A activity contributed to the sustained activation of NF-κB signaling, which has an important role in hyperglycemia-induced inflammatory responses and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes.

Hyperglycemia is an important risk factor for the pathophysiological development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Reversal of the hyperglycemic conditions has been shown to attenuate the cardiovascular complications associated with diabetes mellitus (Cai et al., 2006; Shirpoor et al., 2009). We and others have reported that HG induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes (Guleria et al., 2011; Rajamani and Essop, 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Previous studies have shown that activation of NF-κB signaling is involved in HG-induced cell apoptosis (Ho et al., 2006; Kuo et al., 2011; Nan et al., 2011), and we have shown similar findings in HG-stimulated cardiomyocytes. Inhibition of the nuclear translocation of NF-κB prevented HG-induced activation of apoptotic signaling and the gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1. It has been shown that a number of cytokines and inflammatory factors are abnormally expressed in diabetic myocardium and exacerbate diabetes associated cardiac dysfunction (Aso et al., 2003; Drimal et al., 2008; Younce et al., 2010). These NF-κB regulated inflammatory cytokines are involved in hyperglycemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Dhingra et al., 2009; Hamid et al., 2011; Younce et al., 2010). Our results are consistent with these observations and confirmed that HG-induced activation of NF-κB signaling and secretion of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 had a key role in hyperglycemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

NF-κB activation is tightly controlled by the IKK complex, which consists of two catalytic subunits IKKα and IKKβ and a non-catalytic regulatory subunit IKKγ, together with its downstream substrate IκBα (Ghosh and Karin, 2002; Hacker and Karin, 2006). Activation of IKK activity requires phosphorylation of either IKKα or IKKβ. The upstream molecules that regulate the activation of IKK are not clear. TAK1 (transforming growth factor beta activated kinase-1) and MEKK3 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 3) have been shown to be involved in regulation of the phosphorylation and activation of IKK (Wang et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). Activated IKK induces phosphorylation of IκBα, which leads to poly-ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of IκBα, followed by NF-κB translocation into the nucleus, resulting in increased transcription of responsive genes. Appropriate termination of NF-κB stimulated transcriptional activity is required to maintain cellular responsiveness to subsequent stimuli. NF-κB activation induces rapid resynthesis of IκBα, and newly synthesized IκBα inhibits NF-κB/DNA interaction and exports NF-κB back to the cytoplasm, leading to termination of NF-κB-dependent transcriptional responses (Hoffmann et al., 2002). This negative feedback loop is regulated by the phosphorylation status of the upstream kinase IKK. Dephosphorylation of IKK is required to prevent phosphorylation of resynthesized IκBα, and is a prerequisite for termination of NF-κB activation (Delhase et al., 1999). In the present study, HG-induced activation of NF-κB is sustained rather than transient, as we observed that nuclear translocation and activation of NF-κB remained significantly increased following 48 h of HG exposure, including increased phosphorylation of IKK and IκBα, at 24 to 48 h. Furthermore, the expression of IκBα remained at a low level after 48 h of HG exposure, suggesting that NF-κB-mediated resynthesized IκBα may be continuously phosphorylated and degraded by IKK. Previous studies have shown that PP2A, a family of phosphoserine- and phosphothreonine-specific enzymes, is involved in regulation of the dephosphorylation of IKK and IκBα (Miskolci et al., 2003; Witt et al., 2009). Although previous studies have shown that PP2A is activated by HG in endothelial cells and pancreatic beta-cells (Du et al., 2010; Ravnskjaer et al., 2006), our results showed that PP2A activity was significantly suppressed by HG in cardiomyocytes, as demonstrated by sustained tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac following HG exposure, suggesting that the regulation of PP2A activation by HG may be cell type specific. Inhibition of PP2A activation by okadaic acid, or silencing the expression of PP2Ac in cardiomyocytes, further enhanced HG-induced sustained phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and subsequent degradation of IκBα. Our results indicate that HG-induced suppression of PP2A activity leads to sustained phosphorylation of IKK, disrupting the negative feedback loop in post-degradation resynthesis of IκBα, resulting in sustained phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα and activation of NF-κB. Recent studies have shown that constitutively activated NF-κB signaling may be associated with the development of diabetes-induced complications, including diabetic cardiomyopathy (Chen et al., 2003; Green et al., 2011; Mariappan et al., 2010). We also observed phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and degradation of IκBα in hearts from ZDF rats, accompanied by decreased PP2A activity. These data further support the concept that the HG-induced impairment of PP2A has an important role in mediating constitutively activated NF-κB signaling under diabetic conditions and that the sustained activation of NF-κB signaling may have a critical role in the process of diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Previous studies have shown that vitamin A and its metabolites inhibit several types of inflammatory reactions (Long et al., 2011; Villamor and Fawzi, 2005); and that activated NF-κB signaling is associated with an increased inflammatory response in vitamin A deficiency (Austenaa et al., 2004; Gatica et al., 2005; Reifen et al., 2002). We observed that ATRA and LGD1069 inhibited the activation of NF-κB and NF-κB-mediated gene expression of IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1, indicating that the protective effects of RAR and RXR ligands, on cardiomyocytes, are mediated (at least in part) through regulation of NF-κB signaling. We showed that HG mediated a decrease in PP2A activation, which was involved in the sustained phosphorylation of IKK and degradation of IκBα. HG-induced suppression of PP2A activity was abrogated by ATRA and LGD1069. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of ATRA and LGD1069 on IKK/NF-κB signaling was abolished by okadaic acid and silencing the expression of PP2Ac, indicating that the inhibitory effect of ATRA and LGD1069 on NF-κB is regulated through activation of PP2A. Increased PP2A activity results in dephosphorylation of IKK and IκBα, and prevents dissociation of the IκBα-p65-p55 complex, leading to inhibition of HG-stimulated NF-κB-dependent gene transcription in cardiomyocytes.

The phosphorylation of the PP2A catalytic subunit (PP2Ac) at Y307 leads to inactivation of PP2A. It has been reported that p60v-src, p56lck, epidermal growth factor receptors, and insulin receptors (IR) are involved in the regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac (Barisic et al., 2010; Chen et al., 1992; Hu et al., 2009). A recent study has shown that glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) regulates tyrosine phosphorylation and inactivation of PP2Ac, via protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (Yao et al., 2011). The activation of GSK3β is regulated by the linear signaling cascade IR/IRS/PI3K/Akt (Frame and Cohen, 2001). Activated Akt leads to serine phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β. In diabetes and insulin resistance, the signaling cascade IR/IRSs/PI3K/Akt is impaired, which results in increased GSK3β activity (Eldar-Finkelman et al., 1999; Henriksen and Dokken, 2006). The increased GSK3β activity may contribute to HG-induced inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac. A previous study has shown that RA improves insulin resistance and decreases the blood glucose level, through activation of IRS-2/Akt signaling (Li et al., 2005). We also observed that RA promoted phosphorylation of Akt in HG-stimulated cardiomyocytes (data not shown), and therefore the RA mediated inhibitory effect on HG-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PP2Ac, may be mediated through activation of IRS/Akt and subsequent inhibition of GSK3β signaling. It has been reported that the plasma vitamin A level is significantly decreased in type 1 diabetic patients (Baena et al., 2002; Basu et al., 1989). We also reported that RA-induced transcriptional activity of RAR and RXR is impaired under hyperglycemic conditions, and that a higher level of ligands is required to maintain normal cellular function mediated by RAR and RXR, in response to HG stimulation (Singh et al., 2011). Combined with the above data, it is likely that the HG-induced decrease in PP2A activity may be also due to impaired RA signaling, in which normal PP2A activation was not maintained under hyperglycemic conditions. This may serve as an alternative mechanism of HG-induced sustained activation of NF-κB signaling in cardiomyocytes. Targeting the specific RAR and RXR-mediated signaling event, may restore the normal feedback loop involved in terminating the activation of NF-κB signaling, leading to reversal of NF-κB-mediated inflammation and cellular injury. Our results also suggest that inhibition of NF-κB and its downstream effectors, may account for a significant aspect of the beneficial effects of RAR and RXR ligands, against hyperglycemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and dysfunction.

In conclusion, our results showed that sustained activation of NF-κB signaling is involved in the high glucose-induced inflammatory response and cell apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Activation of RAR and RXR signaling inhibited high glucose-induced activation of NF-κB signaling and NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses. The molecular mechanisms by which RA inhibits the activation of NF-κB, appears to involve the inhibition of phosphorylation of IKK/IκBα and degradation of IκBα, through activation of PP2A. The interactions between RA/RAR/RXR and NF-κB signaling may have important implications in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy, and specific RAR and RXR subtypes could provide possible therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of diabetic cardiomyopathy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1R01 HL091902). This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, Temple, Texas.

Contract grant sponsor: NIH

Contract grant number: 1R01 HL091902

REFERENCES

- 1.Anest V, Hanson JL, Cogswell PC, Steinbrecher KA, Strahl BD, Baldwin AS. A nucleosomal function for IkappaB kinase-alpha in NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. Nature. 2003;423(6940):659–663. doi: 10.1038/nature01648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aso Y, Okumura K, Yoshida N, Tayama K, Kanda T, Kobayashi I, Takemura Y, Inukai T. Plasma interleukin-6 is associated with coagulation in poorly controlled patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2003;20(11):930–934. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austenaa LM, Carlsen H, Ertesvag A, Alexander G, Blomhoff HK, Blomhoff R. Vitamin A status significantly alters nuclear factor-kappaB activity assessed by in vivo imaging. FASEB J. 2004;18(11):1255–1257. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1098fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baena RM, Campoy C, Bayes R, Blanca E, Fernandez JM, Molina-Font JA. Vitamin A retinol binding protein and lipids in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(1):44–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011;13(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin AS., Jr Series introduction: the transcription factor NF-kappaB and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(1):3–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barisic S, Schmidt C, Walczak H, Kulms D. Tyrosine phosphatase inhibition triggers sustained canonical serine-dependent NFkappaB activation via Src-dependent blockade of PP2A. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(4):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(15):1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basu TK, Tze WJ, Leichter J. Serum vitamin A and retinol-binding protein in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50(2):329–331. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battiprolu PK, Gillette TG, Wang ZV, Lavandero S, Hill JA. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2010;7(2):e135–e143. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bierhaus A, Schiekofer S, Schwaninger M, Andrassy M, Humpert PM, Chen J, Hong M, Luther T, Henle T, Kloting I, Morcos M, Hofmann M, Tritschler H, Weigle B, Kasper M, Smith M, Perry G, Schmidt AM, Stern DM, Haring HU, Schleicher E, Nawroth PP. Diabetes-associated sustained activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB. Diabetes. 2001;50(12):2792–2808. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai L, Li W, Wang G, Guo L, Jiang Y, Kang YJ. Hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis in mouse myocardium: mitochondrial cytochrome C-mediated caspase-3 activation pathway. Diabetes. 2002;51(6):1938–1948. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai L, Wang Y, Zhou G, Chen T, Song Y, Li X, Kang YJ. Attenuation by metallothionein of early cardiac cell death via suppression of mitochondrial oxidative stress results in a prevention of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8):1688–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrasekar B, Smith JB, Freeman GL. Ischemia-reperfusion of rat myocardium activates nuclear factor-KappaB and induces neutrophil infiltration via lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine. Circulation. 2001;103(18):2296–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.18.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Martin BL, Brautigan DL. Regulation of protein serine-threonine phosphatase type-2A by tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1992;257(5074):1261–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1325671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Parsons S, Brautigan DL. Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein phosphatase 2A in response to growth stimulation and v-src transformation of fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(11):7957–7962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S, Khan ZA, Cukiernik M, Chakrabarti S. Differential activation of NF-kappa B and AP-1 in increased fibronectin synthesis in target organs of diabetic complications. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284(6):E1089–E1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00540.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhary R, Baker KM, Pan J. All-trans retinoic acid prevents angiotensin II- and mechanical stretch-induced reactive oxygen species generation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2008a;215(1):172–181. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choudhary R, Palm-Leis A, Scott RC, 3rd, Guleria RS, Rachut E, Baker KM, Pan J. All-trans retinoic acid prevents development of cardiac remodeling in aortic banded rats by inhibiting the renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008b;294(2):H633–H644. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01301.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen P, Holmes CF, Tsukitani Y. Okadaic acid: a new probe for the study of cellular regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15(3):98–102. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90192-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datta PK, Lianos EA. Retinoic acids inhibit inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1999;56(2):486–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IkappaB kinase activity through IKKbeta subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284(5412):309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhingra S, Sharma AK, Arora RC, Slezak J, Singal PK. IL-10 attenuates TNF-alpha-induced NF kappaB pathway activation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82(1):59–66. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drimal J, Knezl V, Navarova J, Nedelcevova J, Paulovicova E, Sotnikova R, Snirc V, Drimal D. Role of inflammatory cytokines and chemoattractants in the rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetic heart failure. Endocr Regul. 2008;42(4):129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du Y, Kowluru A, Kern TS. PP2A contributes to endothelial death in high glucose: inhibition by benfotiamine. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299(6):R1610–R1617. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00676.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eldar-Finkelman H, Schreyer SA, Shinohara MM, LeBoeuf RC, Krebs EG. Increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity in diabetes- and obesity-prone C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes. 1999;48(8):1662–1666. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J. 2001;359(Pt 1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatica L, Alvarez S, Gomez N, Zago MP, Oteiza P, Oliveros L, Gimenez MS. Vitamin A deficiency induces prooxidant environment and inflammation in rat aorta. Free Radic Res. 2005;39(6):621–628. doi: 10.1080/10715760500072214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granic I, Dolga AM, Nijholt IM, van Dijk G, Eisel UL. Inflammation and NF-kappaB in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(4):809–821. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green CJ, Pedersen M, Pedersen BK, Scheele C. Elevated NF-{kappa}B Activation Is Conserved in Human Myocytes Cultured From Obese Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Attenuated by AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Diabetes. 2011 doi: 10.2337/db11-0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guleria RS, Choudhary R, Tanaka T, Baker KM, Pan J. Retinoic acid receptor-mediated signaling protects cardiomyocytes from hyperglycemia induced apoptosis: role of the renin-angiotensin system. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(5):1292–1307. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hacker H, Karin M. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Sci STKE. 2006;2006(357):re13. doi: 10.1126/stke.3572006re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamid T, Guo SZ, Kingery JR, Xiang X, Dawn B, Prabhu SD. Cardiomyocyte NF-kappaB p65 promotes adverse remodelling, apoptosis, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89(1):129–138. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henriksen EJ, Dokken BB. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7(11):1435–1441. doi: 10.2174/1389450110607011435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho FM, Lin WW, Chen BC, Chao CM, Yang CR, Lin LY, Lai CC, Liu SH, Liau CS. High glucose-induced apoptosis in human vascular endothelial cells is mediated through NF-kappaB and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway and prevented by PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Cell Signal. 2006;18(3):391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The IkappaB-NF-kappaB signaling module: temporal control and selective gene activation. Science. 2002;298(5596):1241–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hofmann MA, Schiekofer S, Isermann B, Kanitz M, Henkels M, Joswig M, Treusch A, Morcos M, Weiss T, Borcea V, Abdel Khalek AK, Amiral J, Tritschler H, Ritz E, Wahl P, Ziegler R, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with diabetic nephropathy show increased activation of the oxidative-stress sensitive transcription factor NF-kappaB. Diabetologia. 1999;42(2):222–232. doi: 10.1007/s001250051142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu X, Wu X, Xu J, Zhou J, Han X, Guo J. Src kinase up-regulates the ERK cascade through inactivation of protein phosphatase 2A following cerebral ischemia. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo WW, Wang WJ, Lin CW, Pai P, Lai TY, Tsai CY. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion-induced apoptosis is mediated via the JNK-dependent activation of NF-kappaB in cardiomyocytes exposed to high glucose. J Cell Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Hansen PA, Xi L, Chandraratna RA, Burant CF. Distinct mechanisms of glucose lowering by specific agonists for peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor gamma and retinoic acid X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(46):38317–38327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Libermann TA, Baltimore D. Activation of interleukin-6 gene expression through the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(5):2327–2334. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long KZ, Garcia C, Ko G, Santos JI, Al Mamun A, Rosado JL, DuPont HL, Nathakumar N. Vitamin A modifies the intestinal chemokine and cytokine responses to norovirus infection in Mexican children. J Nutr. 2011;141(5):957–963. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.132134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mariappan N, Elks CM, Sriramula S, Guggilam A, Liu Z, Borkhsenious O, Francis J. NF-kappaB-induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in type II diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85(3):473–483. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miskolci V, Castro-Alcaraz S, Nguyen P, Vancura A, Davidson D, Vancurova I. Okadaic acid induces sustained activation of NFkappaB and degradation of the nuclear IkappaBalpha in human neutrophils. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;417(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgan MJ, Liu ZG. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21(1):103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murarka S, Movahed MR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2010;16(12):971–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.07.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nan WQ, Shan TQ, Qian X, Ping W, Bing GA, Ying LL. PPARalpha agonist prevented the apoptosis induced by glucose and fatty acid in neonatal cardiomyocytes. J Endocrinol Invest. 2011;34(4):271–275. doi: 10.1007/BF03347084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palm-Leis A, Singh US, Herbelin BS, Olsovsky GD, Baker KM, Pan J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases mediate the inhibitory effects of all-trans retinoic acid on the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54905–54917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel S, Santani D. Role of NF-kappa B in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its associated complications. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61(4):595–603. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purev E, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. PP2A interaction with Rb2/p130 mediates translocation of Rb2/p130 into the nucleus in all-trans retinoic acid-treated ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(4):1027–1034. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajamani U, Essop MF. Hyperglycemia-mediated activation of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway results in myocardial apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(1):C139–C147. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00020.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramirez CJ, Haberbusch JM, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. Retinoic acid induced repression of AP-1 activity is mediated by protein phosphatase 2A in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96(1):170–182. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravnskjaer K, Boergesen M, Dalgaard LT, Mandrup S. Glucose-induced repression of PPARalpha gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells involves PP2A activation and AMPK inactivation. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36(2):289–299. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reifen R, Nur T, Ghebermeskel K, Zaiger G, Urizky R, Pines M. Vitamin A deficiency exacerbates inflammation in a rat model of colitis through activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and collagen formation. J Nutr. 2002;132(9):2743–2747. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schainberg A, Ribeiro-Oliveira A, Jr, Ribeiro JM. Is there a link between glucose levels and heart failure? An update. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;54(5):488–497. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302010000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shirpoor A, Salami S, Khadem-Ansari MH, Ilkhanizadeh B, Pakdel FG, Khademvatani K. Cardioprotective effect of vitamin E: rescues of diabetes-induced cardiac malfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in rat. J Diabetes Complications. 2009;23(5):310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh AB, Guleria RS, Nizamutdinova IT, Baker KM, Pan J. High glucose-induced repression of RAR/RXR in cardiomyocytes is mediated through oxidative stress/JNK signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcp.23005. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Villamor E, Fawzi WW. Effects of vitamin a supplementation on immune responses and correlation with clinical outcomes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(3):446–464. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.446-464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wan F, Lenardo MJ. The nuclear signaling of NF-kappaB: current knowledge, new insights, and future perspectives. Cell Res. 2010;20(1):24–33. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. 2001;412(6844):346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Witt J, Barisic S, Schumann E, Allgower F, Sawodny O, Sauter T, Kulms D. Mechanism of PP2A-mediated IKK beta dephosphorylation: a systems biological approach. BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:71. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang J, Lin Y, Guo Z, Cheng J, Huang J, Deng L, Liao W, Chen Z, Liu Z, Su B. The essential role of MEKK3 in TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(7):620–624. doi: 10.1038/89769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao XQ, Zhang XX, Yin YY, Liu B, Luo DJ, Liu D, Chen NN, Ni ZF, Wang X, Wang Q, Wang JZ, Liu GP. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates Tyr307 phosphorylation of protein phosphatase-2A via protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B but not Src. Biochem J. 2011;437(2):335–344. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Younce CW, Wang K, Kolattukudy PE. Hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocyte death is mediated via MCP-1 production and induction of a novel zinc-finger protein MCPIP. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(4):665–674. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu XY, Geng YJ, Liang JL, Lin QX, Lin SG, Zhang S, Li Y. High levels of glucose induce apoptosis in cardiomyocyte via epigenetic regulation of the insulin-like growth factor receptor. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(17):2903–2909. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]