Abstract

Aim

Our primary objective was to describe and determine the feasibility of implementing a care environment targeted pediatric post-cardiac arrest debriefing program. A secondary objective was to evaluate the usefulness of debriefing content items. We hypothesized that a care environment targeted post-cardiac arrest debriefing program would be feasible, well-received, and result in improved self-reported knowledge, confidence and performance of pediatric providers.

Methods

Physician-led multidisciplinary pediatric post-cardiac arrest debriefings were conducted using data from CPR recording defibrillators/central monitors followed by a semi-quantitative survey. Eight debriefing content elements divided, a priori, into physical skill (PS) related and cognitive skill (CS) related categories were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale to determine those most useful (5-point Likert scale: 1 = very useful/5 = not useful). Summary scores evaluated the impact on providers’ knowledge, confidence, and performance.

Results

Between June 2010 and May 2011, 6 debriefings were completed. Thirty-four of 50 (68%) front line care providers attended the debriefings and completed surveys. All eight content elements were rated between useful to very useful (Median 1; IQR 1–2). PS items scored higher than CS items to improve knowledge (Median: 2 (IQR 1–3) vs. 1 (IQR 0–2); p < 0.02) and performance (Median: 2 (IQR 1–3) vs. 1 (IQR 0–1); p < 0.01).

Conclusions

A novel care environment targeted pediatric post-cardiac arrest pediatric debriefing program is feasible and useful for providers regardless of their participation in the resuscitation. Physical skill related elements were rated more useful than cognitive skill related elements for knowledge and performance.

Keywords: Pediatric, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Debriefing

1. Introduction

Pediatric cardiac arrest is an important public health problem with approximately 16,000 cardiac arrests occurring each year in the United States.1,2 Unfortunately, resuscitation attempts are plagued by poor CPR quality during both in and out-of-hospital arrests.3–8 The addition of CPR recording feedback-enabled devices alone, without debriefing, has improved CPR quality in cardiac arrests of adults,6,7 but to date has not improved short-term survival outcomes when evaluated in large multi-center randomized trials.9

In contrast, the recent application of performance debriefing – quantitative review of resuscitation data with front line care providers – has been highlighted as a promising technique to not only improve adult CPR quality, but more importantly to improve short term survival outcomes.10 While initially founded in military training, debriefing now has many applications, including medical education, where its effectiveness in simulation training is well established as the most important part of simulation and crucial to the learning process.11,12 Quantitative debriefing refers to programs building upon classic qualitative debriefing (i.e. facilitated discussions of participant actions and thought processes with constructive feedback without the use of resuscitation quantitative data) by the addition of actual quantitative patient information gathered from bedside CPR recording devices, patient monitors, and resuscitation records.10,12,13

Despite the success of a similar modified debriefing technique with dedicated adult resuscitation teams,10 a Pediatric ICU care environment targeted post-cardiac arrest debriefing program with quantitative data analysis and review has never been reported. Given the quality of pediatric CPR frequently does not meet current resuscitation targets, even with the assistance of CPR recording automated feedback devices,14–17 and the differences in arrest etiologies,18 physiology, and chest mechanics19 between children and adults, the initiation of pediatric post-cardiac arrest debriefing using quantitative data after real pediatric cardiac arrest is novel and warranted.

The primary objective of this study was to describe and determine the feasibility of implementing this type of novel educational program. A secondary objective was to evaluate the program’s acceptance, and through a provider survey, help guide refinement and development of future pediatric debriefing programs. We hypothesized that a care environment targeted post-cardiac arrest debriefing program would be feasible, well-received, and result in improved self-reported knowledge, confidence, and performance of pediatric providers whether or not they attended the actual resuscitation event. This study fulfills an important first step necessary to design future studies that will formally and quantitatively evaluate performance debriefings and their effect on pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitations and ultimately, survival outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This pilot study was designed to describe and semi-quantitatively evaluate a novel multidisciplinary, peer-led, care environment targeted pediatric-focused post-cardiac arrest debriefing program in a tertiary pediatric intensive care unit.

2.2. Subjects

All pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) front line care providers regardless of their participation in the resuscitation event were invited to voluntarily attend the debriefing through flyers and a group email. The debriefings were multidisciplinary with attendance of PICU physicians (residents, fellows, and attendings), registered nurses (RN), respiratory therapists (RT), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) specialists, and consultants (e.g. cardiologists and electrophysiologists) with 20–34 attendees at each review.

2.3. CPR recording feedback enabled defibrillator

The Heartstart MRx defibrillator with Q-CPR option, jointly designed by Philips Health Care (Andover, MA) and the Laerdal Medical Corporation (Stavanger, Norway) was used to collect quantitative CPR/resuscitation data for the debriefings. Each defibrillator has an oval pad that is placed on the lower part of the sternum (dimensions: 127 mm × 62 mm × 24 mm). The pad is fitted with an accelerometer and a force sensor to detect chest compression (CC) quantitative data, whereas changes in thoracic impedance measured via defibrillator pads are used to obtain ventilation data. The system records CPR quality parameters (such as depth and rate) as well as electrocardiographic, end tidal CO2, and defibrillation data. It also gives real-time feedback if CPR is not meeting preset parameters as according to the 2005 American Heart Association20 guideline recommendations. This quantitative information is stored internally for later download and analysis.14

2.4. Description of the resuscitation review program

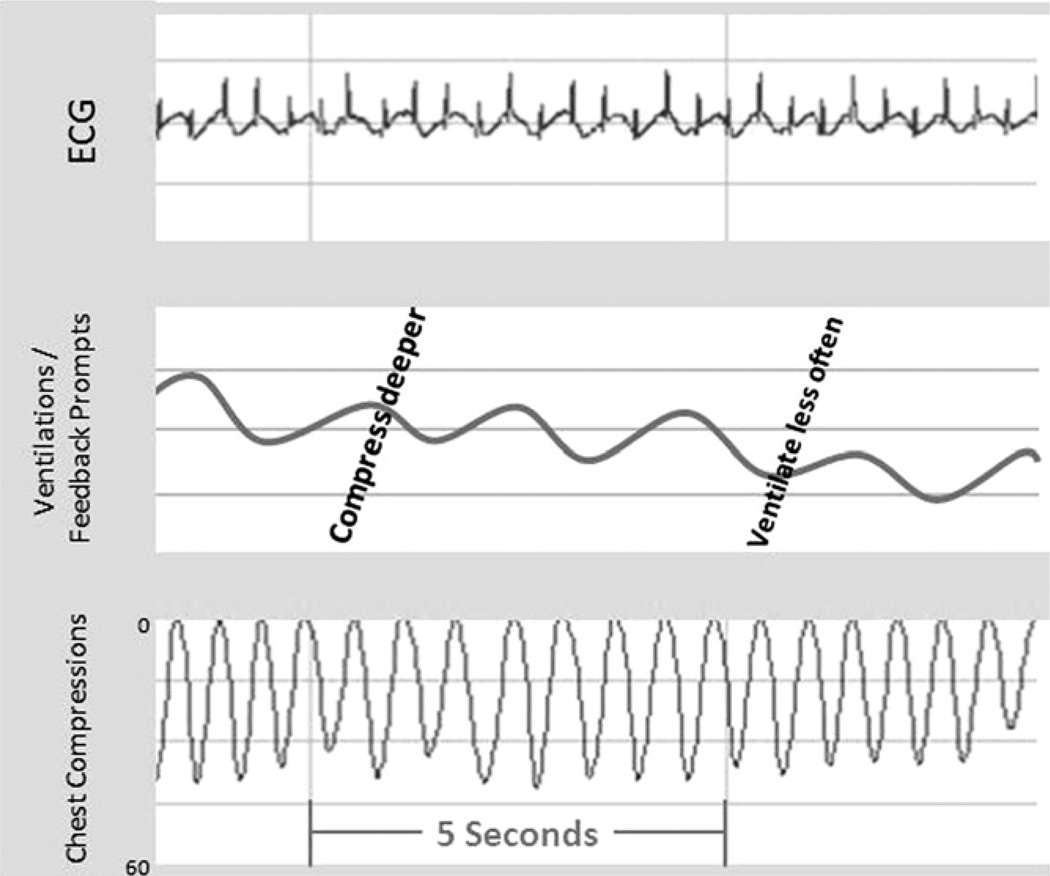

After each cardiac arrest utilizing Q-CPR technology, a pediatric critical care fellow physician with support from content experts (authors RMS, VMN, and RAB) reviewed the pre-arrest and resuscitation documentation, as well as the Q-CPR data from the Heartstart MRx defibrillator using a Windows-based program (Q-CPR Review; Version 2.1.0.0, Laerdal Medical, Stavanger, Norway). When available, monitor data was correlated with the Q-CPR data and the resuscitation record. A presentation using Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond WA) was created with multidisciplinary input. The presentation slides were used to present visual aids such as Q-CPR screenshots, (Fig. 1) monitor data such as ECG and pulse oximetry tracings, arterial line waveforms, ETCO2 values, and relevant literature to supplement the 60 min facilitated debriefing. A pediatric critical care fellow with specific training in debriefing (i.e. completed the Simulation Facilitator and Video Debriefing in Simulation Courses at the Center for Simulation, Advanced Education, and Innovation at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia) facilitated each review.

Fig. 1.

Example of representative CPR quantitative recording. This recording enables practitioners to review ECG, ventilation, and chest compression data after actual cardiac arrests. Note prompts given to rescuers to “compress deeper” and “ventilate less often.”.

Modified from Sutton et al.26

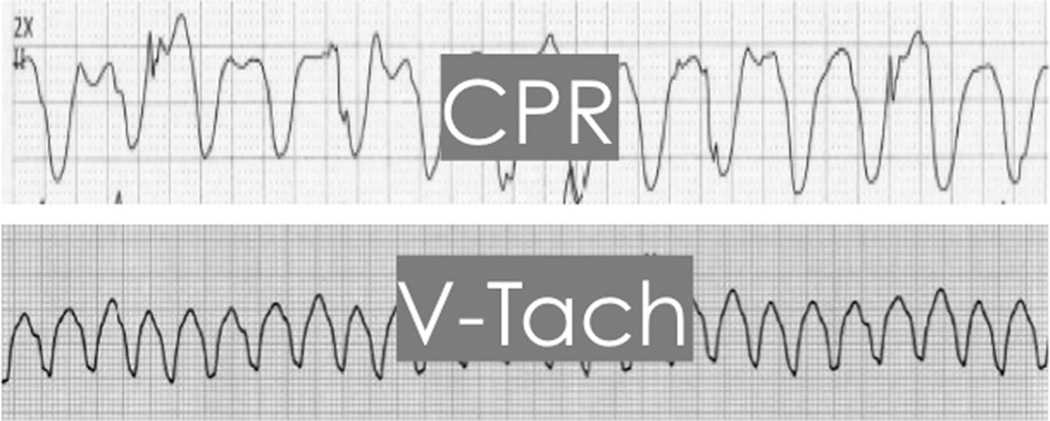

Each presentation began with a review of ground rules for participation (i.e. protected forum, professional behavior to foster blame-free discussion), as well as basic event information including: patient age; time and date of event; duration of event; and patient survival outcome. Background patient information including pertinent medical history/admission diagnosis, procedures, labs, and test results were used to introduce the case. Vital signs and medical management within 24 h of cardiac arrest were reviewed to identify pre-arrest characteristics. The formal review of the resuscitation event could include any or all of the following data: Q-CPR screenshots (Fig. 1), specifically: pre-code rhythm; interruptions in CCs; defibrillation attempts with pre and post shock rhythm; ventilation quality with attention to rate (e.g. avoidance of excessive ventilation); CC quality (specifically average rate of CC’s and average number of CC’s meeting depth goals), percentage of no-flow time, ventilation rate, percentage of CC’s without full release (leaning), as well as monitor data (invasive arterial line pressures, ETCO2 and pulse oximetry waveforms and values). Using this objective quantitative data, we calculated and reported percentages of CPR meeting AHA criteria and were able to detail specific areas related to CPR performance that could be improved with both visual and numerical data. In addition, opportunities for improved care (e.g. unanswered/uncorrected feedback from MRx), incorrect rhythm recognition with inappropriate treatment (e.g. wrong defibrillation energy), and communication/documentation challenges were reviewed (See Fig. 2). Exemplary performance was also highlighted to ensure positive reinforcement of excellent resuscitation skills. Each presentation concluded with a snapshot of the entire resuscitation event on one slide to evaluate trends in CPR quality and when available, patient follow up data.

Fig. 2.

Example of quantitative information presented to bedside providers during review of the cardiac arrest. The similarity of the appearance of ventricular tachycardia and CPR artifact on an ECG tracing was highlighted to the debriefing participants with this slide. The code team recorder had initially interpreted and documented the rhythm as ventricular tachycardia (a shockable rhythm) on the bedside record whereas the physician code leader recognized PEA with CPR artifact. This was not recognized until the code ended and documentation was reviewed. This example demonstrated the importance of communication across disciplines during a resuscitation.

As part of the design of this study to evaluate the program, eight potential educational content items relating to resuscitation were discussed at every pediatric debriefing. These content items were: (1) no-flow time (i.e. limiting pauses in CC delivery); (2) chest compression quality; (3) end tidal CO2 use to guide CC quality; (4) defibrillation (irrespective if a shockable rhythm was encountered during the discussion of the event); (5) communication/teamwork; (6) rhythm recognition; (7) medications; and (8) pediatric cardiac arrest physiology. Supporting literature was discussed with particular attention to studies demonstrating improved patient outcomes. Finally, a mental health specialist was available for care providers as needed.

2.5. Evaluation and analysis of the pediatric post-cardiac arrest debriefing program

A voluntary anonymous eleven-question survey created through SurveyMonkey™ (Palo Alto, CA) was emailed to front-line care providers who had attended at least one debriefing. Eight aspects of the debriefing content, a priori divided into physical skill (PS) related (no-flow time, chest compression quality, end tidal CO2, defibrillation) and cognitive skill (CS) related (communication, rhythm recognition, medications, arrest physiology) were evaluated by respondents to determine those most useful overall (5 point Likert scale (1 = very useful/5 = not useful)). Subjects were also asked which of those same items were most useful for improving their knowledge, performance, and confidence. A score (0–4) was then calculated by adding the number of items selected in each category (PS related vs. CS related) to improve providers’ knowledge, confidence, and performance and compared across categories by Wilcoxon Rank sum. Standard descriptive statistics were also calculated. Participants were surveyed on their acceptance of the program and free text feedback was encouraged. Each participant completed only one survey each to avoid duplication of data. The Institutional Review Board at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia granted exemption from review.

3. Results

Between June 2010 and May 2011, 6 debriefings were completed. The average time lapse between the cardiac arrest and the debriefings was 21 ± 13 days. Fifty surveys were administered with 34 (68%) completed. The median number of debriefings attended by survey respondents was 2 (IQR 1–3). Physicians with critical care training (attendings and fellows) attended more debriefings compared to other disciplines (median 3 (IQR 2–3) vs. 1 (IQR 1–1); (p < 0.01)). Distribution of survey respondents was: registered nurses (15%), attending physicians (35%), fellows (27%), residents (9%), ECMO specialists (6%), and RTs (9%).

The eight aspects of debriefing content were rated between very useful to useful with median scores of 1 in each domain (Table 1). When rating usefulness of debriefing content items divided into categories of knowledge, confidence, and performance, PS items scored significantly higher compared to CS items for improving knowledge (Median: 2 (IQR 1–3) vs. 1 (IQR 0–2); p < 0.02) and performance (Median: 2 (IQR 1–3) vs. 1 (IQR 0–1); p < 0.01); there was no difference in the confidence category (Median: 2 (IQR 1–2) vs. 1 (IQR 0–2); p = 0.09). Participants found the environment of the debriefing program fostered open discussion of patient safety issues with the exception of one responder who noted that the large public group environment made it difficult to share comments.

Table 1.

Likert scale scores (1 = very useful/5 = not useful to improve understanding) across categories. Data presented as medians (interquartile ranges).

| Physical |

Cognitive |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC quality | NFT | Defib | ETCO2 | Phys | Rhythm | Meds | Comm | |

| Overall usefulness score | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) |

CCQ, chest compression quality; NFT, no-.ow time; De.b, de.brillation; ETCO2, end tidal CO2; Phys, arrest physiology; Rhythm, rhythm recognition; Meds, medications usage; Comm, communication.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to semi-quantitatively describe a novel pediatric-focused multidisciplinary care environment targeted post-cardiac arrest debriefing program. In contrast to previously published adult studies on performance debriefings,10 which have classically targeted the code team members who were at the actual resuscitation, this investigation evaluates a post-cardiac arrest debriefing program targeted to the care environment rather than the specific code team (i.e. participants may or may not have participated in the actual resuscitation event). With the relative higher frequency of in-hospital adult cardiac arrest21 compared to pediatric events, adult code team members can have exposure to multiple debriefings even within a one month code team rotation. However, due to the relative rarity of pediatric events,22,23 very few PICU staff would be exposed to the educational aspects of the debriefings if only the code team was involved. In short, by targeting the care environment, our goal was to change “culture” and maximize the educational impact from each resuscitation rather than a specific team’s performance.

Further, the pediatric program described in this investigation was multidisciplinary in both creation and presentation. As physicians are typically the minority in code situations, input from nurses and respiratory therapists, who are integral members to successful resuscitation attempts, allowed elucidation of additional areas for improvement. The multidisciplinary approach helped physicians recognize and understand the challenges that the other care providers experience during a code. Ultimately, improved team-work, communication, and in the end pediatric patient outcomes should be anticipated.

Lastly, a common focus of each debriefing was CPR statistics (e.g. CC depth, no flow time), with the impact on the providers likely attributed to the visual information provided by the screenshots. As cardiac arrests occur relatively infrequently in any single given PICU, front line providers are rarely exposed to CPR, and even more rarely perform the actual chest compressions/ventilations. Therefore increasing providers’ exposure to CPR related concepts and most importantly, actual data visually demonstrating their performance in association with these concepts, is very useful to respondents, especially in an academic institution with numerous trainees and new providers.

This investigation establishes that multi-disciplinary debriefing targeted to a care environment is both feasible and useful to improve understanding of 8 components of pediatric resuscitation from cardiac arrest even for providers that were not directly involved in the resuscitation. In our study, the content items we evaluated were rated highly. Our secondary objective was to obtain pilot semi-quantitative information to help guide content of future pediatric debriefing programs. Interestingly, those items relating directly to physical skills were rated as more useful to improve self-reported understanding of pediatric cardiac arrest resuscitation by survey respondents as compared to the cognitive skill items. The apparent superiority of PS related items is likely attributable to how each area is typically taught in medical education. Actual review of physical performance during resuscitation (e.g. performance of quality CPR or actually placing an end tidal carbon dioxide monitor to guide CPR quality) is novel whereas cognitive concepts (e.g. medication dosage and indications, rhythm analysis, and arrest physiology) are easily studied in multiple traditional formats such as classroom education.

Communication may have been rated as less useful to participants due to the format of our debriefings. As we targeted the entire PICU staff, rather than the team of code participants, we never had the entire code team present at the debriefings. Therefore, without audio recording review, communication debriefing (i.e. one of the CS items) was limited. While we were able to discuss some communication topics, such as lack of communication when code sheet documentation did not match reality (Fig. 2), audio review could potentially increase the usefulness of the communication aspect of the debriefings.

A common theme noted in the free text feedback portion of the survey was to increase the frequency/intensity of the program, including the addition of actual audiovisual review of the resuscitation, not just quantitative event data. This was surprising given the privacy and legal concerns that are often voiced when care providers discuss using audiovisual review in performance evaluations. We postulate that the communication and team dynamic aspects of the debriefing would be significantly enhanced with this technology.

In our study, critical care physicians (attendings and fellows) on average attended more debriefings than all other disciplines. This is interesting as other disciplines, particularly registered nurses, far outnumber physicians at resuscitations in our PICU. However, it may be more difficult for non-physicians to attend these reviews for several reasons: participating in bedside care, staffing patterns, and non-clinical days historically not being “in-hospital” for these other providers. As a possible solution to these challenges, we added a conference calling option for the debriefings; however, the utility of this method is limited as much of the debriefing piloted in this investigation was visually based. In the future, we plan to investigate other potential solutions including real-time video conferencing, targeting debriefings to other staffing patterns (i.e. night shift presentations), and possibly performing abbreviated focused and private debriefings immediately after the resuscitation.

While positive feedback regarding the debriefing program was common, in light of our small number of responders, we must highlight the opinion of a responder who thought our format was not entirely conducive to open discussion (“too big and intimidating… I recommend smaller debriefings targeted to the frontline care providers that were present for the resuscitation”). It may be feasible to provide this type of service. Evaluating the utility and acceptance of an alternative format could be interesting and potentially an additional educational option. Adult learning theory supports improved learning when the educational topic is relevant and emotionally affects learners.11 Certainly reviewing a resuscitation exclusively with the resuscitation team would be more relevant and emotionally provocative than our current program. However, the logistics and time commitment required from the leader of the debriefing could be a barrier to such a program. In addition one of the major benefits of the debriefing format piloted in this investigation is that the debriefing targeted to the PICU care environment creates the opportunity for the entire PICU to learn from these infrequent events. Future studies could evaluate which format creates more positive impact on patient care.

This pilot study has several limitations. Our program and survey were both performed in a single institution. In addition, with a 68% survey return rate, while better than several previously published physician-oriented surveys,24,25 our overall number of responders was not as robust as we had hoped. Non-response bias is another concern, given the voluntary participation in the debriefings and survey response. Due to privacy concerns, we did not link participation in an actual code event to debriefing attendance or even survey response. The authors acknowledge that such information would have strengthened the findings from our secondary analysis. However, in an effort to encourage participation and open communication, such data was not collected, and is a limitation of this study. Lastly, our survey was non-validated and evaluated perceptions (self-reported outcomes), rather than actual patient outcomes. However, data from this study should be encouraging. As our debriefing program was well-received, ongoing pediatric CPR data collection will allow the evaluation of the effect of pediatric-focused post-cardiac arrest debriefing to improve CPR quality and short-term survival outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This investigation marks an important first step in evaluating pediatric-focused post-cardiac arrest debriefings. Our pilot study has demonstrated a multi-disciplinary pediatric post-cardiac arrest quantitative debriefing program targeted to a care environment, rather than a specific code team, is both feasible and useful for pediatric providers. Future studies must be conducted to determine if such a program is effective to improve operational performance and short- and long-term patient outcomes in pediatric resuscitation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dana Edelson from the University of Chicago for her guidance in developing our debriefing program. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Heather Wolfe and Stephanie Tuttle who have supported resuscitation science at the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Financial disclosure

This study was supported by the Laerdal Foundation for Acute Care Medicine and the Endowed Chair of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Robert M. Sutton receives funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (Award Number K23HD062629).

Conflict of interest statement

Unrestricted research grant support: Vinay Nadkarni and Dana Niles from the Laerdal Foundation for Acute Care Medicine; Dana Niles from Laerdal Medical, Inc. Robert Sutton is supported through a career development award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (K23HD062629).

Abbreviations

- AHA

American Heart Association

- CC

chest compression

- CPR

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CS

cognitive skill

- PS

physical skill

Footnotes

A Spanish translated version of the summary of this article appears as Appendix in the final online version at doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.021.

References

- 1.Tress EE, Kochanek PM, Saladino RA, Manole MD. Cardiac arrest in children. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:267–272. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.66528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins DL, Everson-Stewart S, Sears GK, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in children: the resuscitation outcomes consortium epistry-cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2009;119:1484–1491. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abella BS, Sandbo N, Vassilatos P, et al. Chest compression rates during cardiopulmonary resuscitation are suboptimal: a prospective study during inhospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2005;111:428–434. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153811.84257.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abella BS, Alvarado JP, Myklebust H, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005;293:305–310. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wik L, Kramer-Johansen J, Myklebust H, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005;293:299–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abella BS, Edelson DP, Kim S, et al. CPR quality improvement during in-hospital cardiac arrest using a real-time audiovisual feedback system. Resuscitation. 2007;73:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer-Johansen J, Myklebust H, Wik L, et al. Quality of out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation with real time automated feedback: a prospective interventional study. Resuscitation. 2006;71:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer-Johansen J, Edelson DP, Abella BS, Becker LB, Wik L, Steen PA. Pauses in chest compression and inappropriate shocks: a comparison of manual and semi-automatic defibrillation attempts. Resuscitation. 2007;73:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hostler D, Everson-Stewart S, Rea TD, et al. Effect of real-time feedback during cardiopulmonary resuscitation outside hospital: prospective, clusterrandomised trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d512. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelson DP, Litzinger B, Arora V, et al. Improving in-hospital cardiac arrest process and outcomes with performance debriefing. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1063–1069. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2007;2:115–125. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180315539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton RM, Niles D, Meaney PM, et al. “Booster” training; evaluation of instructor-led bedside cardiopulmonary resuscitation skill training and automated corrective feedback to improve cardiopulmonary resuscitation compliance of pediatric basic life support providers during simulated cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e116–e121. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e91271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dine CJ, Gersh RE, Leary M, Riegel BJ, Bellini LM, Abella BS. Improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality and resuscitation training by combining audiovisual feedback and debriefing. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2817–2822. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186fe37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton RM, Niles D, Nysaether J, et al. Quantitative analysis of CPR quality during in-hospital resuscitation of older children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:494–499. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niles D, Nysaether J, Sutton R, et al. Leaning is common during in-hospital pediatric CPR, decreased with automated corrective feedback. Resuscitation. 2009;80:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton RM, Maltese MR, Niles D, et al. Quantitative analysis of chest compression interruptions during in-hospital resuscitation of older children and adolescents. Resuscitation. 2009;80:1259–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McInnes AD, Sutton RM, Orioles A, et al. The first quantitative report of ventilation rate during in-hospital resuscitation of older children and adolescents. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1025–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006;295:50–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maltese M, Castner T, Niles D, et al. Methods for determining pediatric thoracic force-deflection characteristics from cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Stapp Car Crash J. 2008;52:83–105. doi: 10.4271/2008-22-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Heart Association. American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e989–e1004. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merchant RM, Yang L, Becker LB, et al. Incidence of treated cardiac arrest in hospitalized patients in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2401–2406. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donoghue AJ, Nadkarni VM, Elliott M, Durbin D American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Effect of hospital characteristics on outcomes from pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a report from the national registry of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Pediatrics. 2006;118:995–1001. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadel FM, Lavelle JM, Fein JA, Giardino AP, Decker JM, Durbin DR. Assessing pediatric senior residents’ training in resuscitation: fund of knowledge, technical skills, and perception of confidence. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16:73–76. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;1:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thorpe C, Ryan B, McLean SL, et al. How to obtain excellent response rates when surveying physicians. Fam Pract. 2009;1:65–68. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutton RM, Nadkarni V, Abella BS. “Putting it all together” to improve resuscitation quality. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2012;30:105–122. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]