Abstract

Background

Laboratory-based evidence is lacking regarding the efficacy of non-pharmaceutical interventions such as alcohol-based hand sanitizer and respiratory hygiene to reduce the spread of influenza.

Methods

The Pittsburgh Influenza Prevention Project was a cluster-randomized trial conducted in ten Pittsburgh, PA elementary schools during the 2007-2008 influenza season. Children in five intervention schools received training in hand and respiratory hygiene, and were provided and encouraged to use hand sanitizer regularly. Children in five schools acted as controls. Children with influenza-like illness were tested for influenza A and B by RT-PCR.

Results

3360 children participated. Using RT-PCR, 54 cases of influenza A and 50 cases of influenza B were detected. We found no significant effect of the intervention on the primary study outcome of all laboratory confirmed influenza cases (IRR 0.81 95% CI 0.54, 1.23). However, we did find statistically significant differences in protocol-specified ancillary outcomes. Children in intervention schools had significantly fewer laboratory-confirmed influenza A infections than children in control schools, with an adjusted IRR of 0.48 (95% CI 0.26, 0.87). Total absent episodes were also significantly lower among the intervention group than among the control group; adjusted IRR 0.74 (95% CI 0.56, 0.97).

Conclusions

Non-pharmaceutical interventions (respiratory hygiene education and the regular use of hand sanitizer) did not reduce total laboratory confirmed influenza. However the interventions did reduce school total absence episodes by 26% and laboratory-confirmed influenza A infections by 52%. Our results suggest that NPIs can be an important adjunct to influenza vaccination programs to reduce the number of influenza A infections among children.

Keywords: Influenza, Non-pharmaceutical Interventions, School-aged Children, Randomized Controlled Trial, Hand Sanitizer, Absence Surveillance, Laboratory Testing

Introduction

School-aged children were heavily affected by the recent 2009-10 H1N1 pandemic(1) and are considered an important source of influenza transmission during pandemic and seasonal epidemics(2). One study carried out during seasonal epidemics demonstrated that school-age children were the first group to show increases in culture-positive influenza, followed by preschool children, then adults(3). Viboud et al(4) found that 24% of household contacts developed symptoms consistent with influenza within 5 days of illness onset among infected children.

Studies also suggest that alcohol-based hand sanitizer either by itself or in combination with other hygiene measures is effective at reducing absenteeism and reports of respiratory and gastrointestinal illness(5,6,7,8,9). However, no studies have measured the effectiveness of school-based NPIs in reducing the risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza A or B. Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are recommended by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to prevent the spread of influenza(10). These measures – especially when combined as a “set” of activities – take on even greater importance when influenza vaccine is either not available or in short supply, or when vaccine effectiveness may be reduced due to the emergence of a new strain. Cough etiquette and hand hygiene are appealing NPIs because they are inexpensive, straightforward to implement, and inclusive of participants.

Methods

Study population and design

The Pittsburgh Influenza Prevention Project (PIPP), a cluster-randomized trial, was designed to assess the impact of NPIs on the incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza A/B infections among children in ten Pittsburgh K-5 elementary schools. A cluster design was adopted due to logistical constraints of performing the intervention within smaller units of each school and to reduce intervention-control crossover.

Thirteen Pittsburgh elementary schools expressed interest; the largest 10 were selected and assigned to either intervention or control arms by a constrained randomization algorithm using data from the 2006-2007 school year. The random allocation to two arms was created by Dr. Cummings and concealed until intervention assignment. Five schools were randomized to each group, balancing covariates that might be associated with the primary outcome while maintaining an unbiased and valid randomization(11). All enrolled students that were on the school roster at the beginning and end of the school year were considered eligible for the study. Parents and guardians were educated about the study at the beginning of the school year and were given the opportunity to decline participation. Blinding of assignment to the intervention or control group was not possible because of the nature of the intervention.

The primary outcome was an absence episode associated with an influenza-like illness (ILI) that was subsequently laboratory confirmed as influenza A or B. The following CDC definition for ILI was used: fever ≥38°C with sore throat or cough(12). An absence episode was one or more contiguous absent school days during the study period. The secondary outcomes included absence episodes and cumulative days of absence due to ILI, any illness, and all causes. Absence surveillance and the intervention were carried out from 11/1/07 through 4/24/08. Influenza testing of absent students with ILI was performed only during the influenza season; the start of which was determined to be 1/7/2008, based on input from the Allegheny County Health Department combined with results from regional public health laboratories and surveillance systems. Testing stopped on 4/17/08 after no positive test results were obtained for two weeks combined with agreement from local and state public health departments that the flu season was over. This period of influenza testing corresponded precisely with the weeks when greater than 10% of specimens submitted to the US National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System were positive for influenza(13).

Sample size was calculated on the basis of the primary outcome and was chosen to detect a 40% difference in the cumulative incidence of laboratory confirmed influenza among the intervention group compared with the controls assuming 0.05 probability of Type I error and 0.20 probability of Type II error. Sample size was adjusted to account for intra-cluster correlation by methods described by Hayes and Bennett(19). We assumed that: 1) 5% of school children would opt out; 2) 24% of children would experience a respiratory illness that met the ILI definition, 3) 90% of influenza illnesses would occur during the testing period; 4) 75% of the children with influenza-associated ILIs would be tested in a timely manner; and 5) 75% of the influenza infections would test positive using RT-PCR(14,15,16,17,18). We also assumed a coefficient of variation of the true rates between clusters within each group of 0.1 and estimated 10 schools were needed(19). Interim analyses were not conducted and early stopping criteria were not specified.

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at both the University of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Public Schools.

Intervention

A set of NPIs, “WHACK the Flu”, was implemented in intervention schools, with permission from the City of Berkeley Public Health Division, who developed this program. The intervention was modified to add “or sanitize” to the “W” line to read: (W)ash or sanitize your hands often; (H)ome is where you stay when you are sick; (A)void touching your eyes, nose and mouth; (C)over your coughs and sneezes; and (K)eep your distance from sick people(20). The intervention was targeted to all students within intervention schools.

Prior to implementation of the set of NPIs (11/1/07), project staff conducted grade-specific 45 minute presentations at intervention schools regarding influenza, “WHACK the Flu” concepts, and proper hand washing technique and sanitizer use. Hand sanitizer dispensers with 62% alcohol-based hand sanitizer from Purell® (GOJO Industries, Inc, Akron, OH) were installed in each classroom and all major common areas of intervention schools. A goal of four uses per day – upon arrival, before and after lunch, and prior to departure – was taught to students. They were also encouraged to wash hands and/or use additional doses of hand sanitizer as needed. At the onset of the influenza season in January 2008, project staff provided “refresher” trainings at each intervention school. Homeroom teachers were included in both presentations and were asked to reinforce the message and to monitor proper use of hand sanitizer.

Utilization of the intervention was measured in two ways: 1) teachers in classrooms were surveyed regarding observed NPI-related behavior in their students before, during, and after influenza season; and 2) the amount of hand sanitizer used was measured at two week intervals throughout the intervention period.

Detection of Absenteeism, Illness and Infection

Absence surveillance was the primary mechanism for identification of illness in all schools. Outreach workers collected a daily census of absent students from each school. Project personnel then attempted to contact participating parents/guardians within 36 hours to determine the reason for absence, and a tiered questionnaire was administered to collect symptom information. If the ILI definition was met, consent/assent was sought to conduct a home visit.

Within 24 hours of obtaining consent, staff conducted home visits to collect demographic information, symptom data, and laboratory specimens. Two nasal swabs were obtained using test manufacturer-approved sterile Dacron swabs. One swab was used for influenza testing using the QuickVue® Influenza A+B test (Quidel Corp, San Diego, CA). The second nasal swab was delivered on cold pack to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Clinical Virology Laboratory, Pittsburgh, PA for RT-PCR testing (performed within 48 hours). The RT-PCR used viral nucleic acid extract (EasyMag; bioMerieux, Durham, NC) and primer/probe sequences for influenza A, influenza B and influenza A H1 and H3 subtypes (CDC, Atlanta GA). The probes were labeled with 6FAM, CAL Fluor Red 590, or Quasar670 reporter dyes (Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA). An equine arteritis virus internal positive control was included in all assays.

One parent/guardian of the child participating in the home visit was compensated with a $50 grocery store gift card. If their child tested positive for influenza by RT-PCR, they were notified and asked to complete a follow-up survey regarding symptoms of other household members. Data were entered into laptop computers in the field, and were stored in a local Access® (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) database. Data were transferred each night to a secure server at the University of Pittsburgh’s Epidemiology Data Center for storage.

Analysis

Demographic characteristics of children in each study arm were tabulated using percentages for discrete variables, means and medians for continuous variables, and compared using χ2 tests or t-tests respectively(21). Because each individual could experience multiple outcomes, cumulative incidence rates were modeled as Poisson variables. The mean and dispersion of each of the outcome variables were calculated to detect over-dispersion. For outcomes that were determined to be over-dispersed, an additional analysis in which these outcomes were modeled as negative binomial variables was performed(22). To compare cumulative incidences of each outcome in the intervention and control groups, a generalized linear mixed model with a random effect included for school was used to account for clustering of outcomes within schools. Adjustment of outcomes due to differences between study arms in grade distribution, class size, percentage of students receiving school lunch, and race was performed by including these covariates in the generalized linear mixed model. All reported p-values were two-sided and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the standard errors of estimated coefficients of the linear mixed model. Goodness of fit of linear models was assessed using Akaike’s Information Criteria. Analyses were performed using the R statistical package - and SAS in the case of negative binomial regression(23,24).

Results

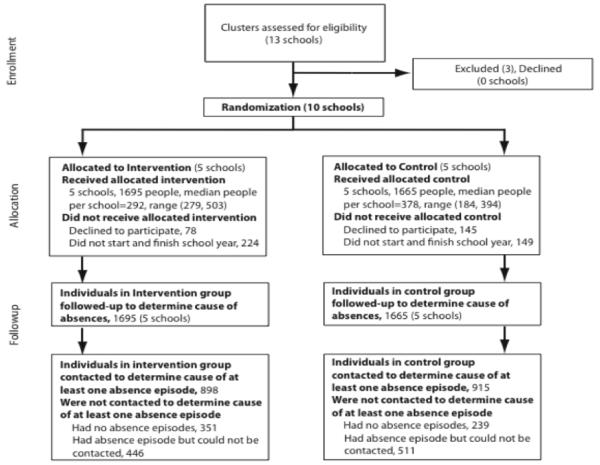

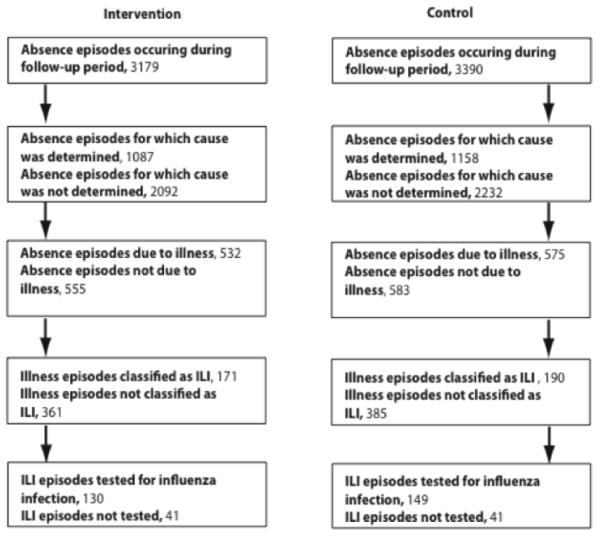

A total of 3360 students participated throughout the study period (Figure 1A). During influenza season, there were 6569 absence episodes. A reason for absence was determined in 2246 cases (34%). Among the remaining 66% of cases, reasons for absence could not be attained due to failed contact with an adult respondent. Reason for failed contact included inaccurate or disconnected contact numbers, non-response by the parent/guardian to repeated phone calls/messages, or unwillingness to provide a reason for the child’s absence. Of the 2246 absences for which a reason was identified, 1107 (49%) were due to an illness of which 361 (33%) met the criteria for ILI, and 279 (77%) had home visits and were tested for influenza (Figure 1B).

Figure 1a.

Enrollment, participation and follow-up of schools and students within schools

Figure 1b.

Follow-up of absence periods

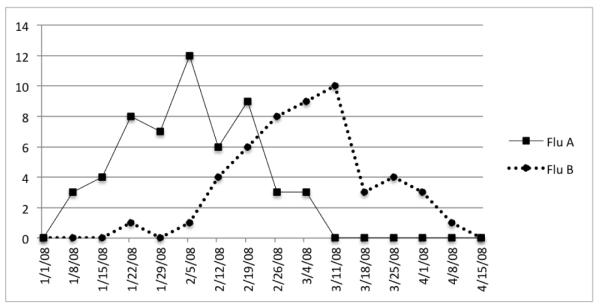

Figure 2 displays the total number of laboratory confirmed influenza A and B cases in both intervention and control schools. 104 (37%) had a positive RT-PCR test for either influenza A or B. One child tested positive for both A and B (at different times). Of the 104 positive test results, 51 were in the intervention and 53 in the control group. Overall, 54 of the cases had influenza A (20 intervention, 34 control) and 50 had influenza B (31 intervention, 19 control). A temporal shift is noted, in that the peak of influenza B follows that of influenza A by approximately 4 weeks. This pattern was consistent with both county and state influenza surveillance data. On average, students used hand sanitizer (1 dose = 0.6 ml of automatically dispensed hand sanitizer) 2.4 times per day in intervention schools. In addition, teacher surveys of observed classroom NPI behavior indicated that students in intervention schools successfully adopted and maintained NPI behaviors throughout influenza season. Students in control schools had rates of NPI usage similar to the pre-season rates in the intervention schools (25).

figure 2.

Total number of laboratory confirmed influenza A and B cases in both intervention and control schools.

In spite of the initial constrained randomization, differences between the intervention and control cohorts were noted with regards to age, race, and participation in school lunch programs (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1), and were taken into consideration in the analysis. With adjustments for grade level, class size, the percentage of school students receiving subsidized school lunch and the racial distribution of the school. Unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) for all outcomes are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 2 (table). We found no difference in the cumulative incidence of laboratory confirmed influenza infections (both A and B) in the intervention compared with the control group, after adjustment (IRR 0.81 95% CI 0.54, 1.23, p=0.33). A statistically significant reduction in the cumulative incidence of absence episodes associated with influenza A illness was found (IRR=0.48 95% CI 0.26, 0.87, p<0.02). We found no statistically significant difference in the cumulative incidence of absence episodes due to influenza B confirmed illness between the two study arms (IRR=1.45 95% CI 0.79, 2.67, p=0.23).

There were fewer absences in the intervention group than in the control group (4710 and 5462 respectively, IRR 0.74 95% CI 0.56, 0.97). The impact of our intervention on total absences was greater in the first two quarters of implementation than in the last two (Q1: 0.68 95% CI (0.51, 0.91), Q2: 0.69 95% CI (0.49, 0.96), Q3: 0.91 95% CI (0.63, 1.30), and Q4: 0.86 95% CI (0.59, 1.26)).

A consistent protective (if not statistically significant) effect of the intervention was found for all outcomes except for laboratory confirmed influenza B (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Total absences, illness-related absences during influenza season, and illness-related absences during the intervention period were over-dispersed. The results using a negative binomial model to fit these outcomes were very similar to coefficients estimated from a Poisson model (Table 1). Similar results were found when using absent days rather than absence episodes (Table 2). The intra-class correlation coefficient for the primary outcome was found to be 0.01 (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1), less than was used to estimate the sample size in the design phase, suggesting outcomes were less clustered within schools than anticipated.

TABLE 1.

Incidence Rate Ratios for Over Dispersed Episode Outcomes Using a Negative Binomial Mixed Model Adjusted for Percentage of Students Receiving Subsidized Lunch (School Level), Percentage of Students Within the School Who are White (School Level), Grade of Student (Grade Level), and Class Size (Class Level)

| Outcome | Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

P (Intervention) |

|---|---|---|

| Total ILI during influenza season | 0.85 (0.53, 1.38) | 0.52 |

| Total ILI during intervention | 0.79 (0.43, 1.45) | 0.45 |

| Absence due to illness during influenza season |

0.85 (0.55, 1.33) | 0.48 |

| Absence due to illness during intervention |

0.75 (0.42, 1.32) | 0.31 |

| Total noninfluenza ILI during influenza season |

0.92 (0.50, 1.69) | 0.79 |

| Total absences during influenza season |

0.80 (0.56, 1.15) | 0.22 |

| Total absences during intervention | 0.74 (0.53, 1.05) | 0.09 |

CI indicates confidence interval; ILI, influenza-like illness.</.>

TABLE 2.

Incidence Rate Ratios for Absent Days Due to Indicated Reason Using a Poisson Mixed Model Adjusted for Percentage of Students Receiving Subsidized Lunch (School Level), Percentage of Students Within the School Who Are White (School Level), Grade of Student (Grade Level), and Class Size (Class Level)

| Outcome | Unadjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

P (Intervention) |

Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

P (Intervention) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory- confirmed |

1.00 (0.52, 1.95) | 0.98 | 0.82 (0.52, 1.28) |

0.38 |

| influenza illness | ||||

| Laboratory- confirmed |

0.74 (0.37, 1.48) | 0.40 | 0.61 (0.37, 1.01) |

0.05 |

| influenza A | ||||

| Laboratory- confirmed |

1.44 (0.75, 2.77) | 0.27 | 1.15 (0.66, 2.02) |

0.62 |

| influenza B | ||||

| Total ILI during influenza season |

0.85 (0.49, 1.48) | 0.57 | 0.83 (0.52, 1.34) |

0.45 |

| Total ILI during intervention |

0.78 (0.40, 1.54) | 0.48 | 0.79 (0.44, 1.41) |

0.42 |

| Absence due to illness during |

0.88 (0.44, 1.74) | 0.71 | 0.88 (0.59, 1.34) |

0.56 |

| influenza season | ||||

| Absence due to illness during intervention |

0.80 (0.41, 1.57) | 0.52 | 0.78 (0.49, 1.25) |

0.30 |

| Total absences during influenza season |

0.90 (0.64, 1.27) | 0.55 | 0.81 (0.59, 1.10) |

0.18 |

| Total absences during intervention |

0.82 (0.59, 1.14) | 0.25 | 0.75 (0.56, 1.00) |

0.05 |

CI indicates confidence interval; ILI, influenza-like illness.

Discussion

PIPP demonstrated that elementary school children using a set of school-based NPIs were able to reduce the cumulative incidence of influenza A by 52% in (IRR=0.48 95% CI 0.26, 0.87) and absenteeism during the total intervention period by 26%. No statistically significant reductions in influenza B or total influenza infections (A + B) were observed. These data indicate that the “WHACK the Flu” intervention combined with regular use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer may help to reduce the spread of influenza A among elementary school children.

Our observation of no statistically significant difference between rates of total laboratory confirmed influenza (A + B), though suggestive of a protective effect, was due in part to a larger number of influenza B cases in the intervention group than in the control group. This observation, though not statistically significant, was surprising. This variation might be due to the fact that influenza B occurred almost entirely in the three youngest grades of our schools, resulting in an effectively smaller sample size for influenza B than influenza A.

The observation of no effect on influenza B could be attributed to differences in the basic biology and epidemiology of B compared with influenza A or to the fact that influenza B infections occurred late in the season, after compliance with the intervention possibly had waned (see Figure 2). It is worth noting that data from the sequential teacher observation surveys did not show a significant reduction in NPI behaviors, but since these surveys were months apart, it is possible that important changes were not detected. Another potential reason that no difference was found may be because most influenza B occurred among young children (K-3). This group may have complied with the intervention less effectively.

The influenza B outbreak began just as the preceding influenza A outbreak was peaking in participating schools and throughout the region. It is possible that residual increased interferon or other innate immunity from recent influenza A infections may have disproportionately led to a temporary decrease in susceptibility to infection with other viruses including influenza B in the control schools. Previous studies have provided suggestive but not consistent results to this question, and further research is needed (26,27).

A limitation of this study was that the reasons for absence could be ascertained for only 34% of absences. This resulted in the study being under-powered for most outcomes. Larger studies during influenza seasons with different distributions of influenza A and B should be performed to better understand these findings, to test for co-circulating viruses such as influenza B, RSV, and others, and to assess the effectiveness of different combinations of NPIs in different age groups.

This study demonstrated that a set of NPIs can be implemented successfully on a large scale within urban schools to reduce absenteeism and the incidence of influenza A. Furthermore, the results provide support for currently recommended respiratory hygiene behaviors during seasonal and pandemic influenza outbreaks and should be included as part of an overall prevention strategy to reduce the burden of influenza among school-aged children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Cooperative Agreement number 5UCI000435-02 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. The authors acknowledge the Pittsburgh Public Schools for their active partnership in this research, as well as the contributions of Dr. Laura Janocko, Dr. Sonali Sanghavi, Ms. Arlene Bullota, and Ms. Charlotte Wang. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Dr. Aidan McDermott and Dr. Justin Lessler for useful discussions. DC and DB received support from the NIH MIDAS program (1U01-GM070708). DC holds a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Welcome Fund.

Support

DC and DB received support from the NIH MIDAS program (1U01-GM070708). DC holds a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Welcome Fund.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Munayco CV, Gomez J, Laguna-Torres VA, et al. Epidemiological and transmissibility analysis of influenza A(H1N1)v in a southern hemisphere setting: Peru. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glezen WP. Emerging infections: Pandemic influenza. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1996;18:64–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glezen WP, Couch RB. Interpandemic influenza in the Houston area, 1974-76. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:587–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803162981103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viboud C, Boelle PY, Cauchemez S, et al. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:684–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowling BJ, Chan KH, Fang VJ, et al. Facemasks and hand hygiene to prevent influenza transmission in households: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:437–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White CG, Shinder FS, Shinder AL, Dyer DL. Reduction of illness absenteeism in elementary schools using an alcohol-free instant hand sanitizer. J Sch Nurs. 2001;17:258–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyer DL, Shinder A, Shinder F. Alcohol-free instant hand sanitizer reduces elementary school illness absenteeism. Fam Med. 2000;32:633–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond B, Ali Y, Fendler E, Dolan M, Donovan S. Effect of hand sanitizer use on elementary school absenteeism. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28:340–6. doi: 10.1067/mic.2000.107276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meadows E, Le Saux N. A systematic review of the effectiveness of antimicrobial rinse-free hand sanitizers for prevention of illness-related absenteeism in elementary school children. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell DM. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, national and community measures. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:88–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.051371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhary MA, Moulton LH. A SAS macro for constrained randomization of group-randomized designs. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2006;83:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortiz JR, Sotomayor V, Uez OC, et al. Strategy to enhance influenza surveillance worldwide. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1271–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.2007-2008 U.S. Influenza Season Summary. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/weeklyarchives2007-2008/07-08summary.htm.

- 14.Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Elizabeth Halloran M, Longini, Nizam A, et al. Population-wide benefits of routine vaccination of children against influenza. Vaccine. 2005;23:1284–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monto AS, Koopman JS, Longini Tecumseh study of illness. XIII. Influenza infection and disease, 1976-1981. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;121:811–822. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox JP, Cooney MK, Hall CE, Foy HM. Influenzavirus infections in Seattle families, 1975-1979. II. Pattern of infection in invaded households and relation to age and prior antibody to occurrence of infection and related illness. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1982;116:228–242. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox JP, Hall CE, Cooney MK, Foy HM. Influenzavirus infections in Seattle families, 1975-1979. I. Study design, methods and the occurrence of infections by time and age. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1982;116:212–227. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monto AS, Sullivan KM. Acute respiratory illness in the community. Frequency of illness and the agents involved. EpidemiolInfect. 1993;110:145–160. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes RJ, Bennett S. Simple sample size calculation for cluster-randomized trials. IntJEpidemiol. 1999;28:319–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. http://archive.naccho.org/modelPractices/Result.asp?PracticeID=152.

- 21.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern applied statistics with S. 4th ed Springler; Berlin: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, et al. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Team RDC. R foundation for statistical computing. 2008. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS . SAS 9.1.3 Help and Documentation. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Publication in Press, Stebbins et al.

- 26.Ackerman E, Longini IM, Jr, Seaholm SK, Hedin AS. Simulation of Mechanisms of Viral Interference in Influenza. Int J Epi. 1990;19(2):444–454. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.2.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGill J, Heusel JW, Legge KL. Innate immune control and regulation of influenza virus infections. J Leuk Bio. 2009;86:803–812. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.