Abstract

Objective

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) is an acute-phase protein that has an important role in the regulation of the innate immune response. The aim of this study was to determine if maternal plasma PTX3 concentration changes in the presence of intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation (IAI) in women with preterm labor (PTL) and intact membranes as well as those with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (preterm PROM).

Study design

This cross-sectional study included women in the following groups: 1) non-pregnant (n=40); 2) uncomplicated pregnancies in the first (n=22), second (n=22) or third (n=71, including 50 women at term not in labor) trimester; 3) uncomplicated pregnancies at term with spontaneous labor (n=49); 4) PTL and intact membranes who delivered at term (n=49); 5) PTL without IAI who delivered preterm (n=26); 6) PTL with IAI (n=65); 7) preterm PROM without IAI (n=25); and 8) preterm PROM with IAI (n=77). Maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations were determined by ELISA.

Results

1) Maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations increased with advancing gestational age (r= 0.62, p<0.001); 2) women at term with spontaneous labor had a higher median plasma PTX3 concentration than those at term not in labor (8.29 ng/mL vs. 5.98 ng/mL, p=0.013); 3) Patients with an episode of PTL, regardless of the presence or absence of IAI and whether these patients delivered preterm or at term, had a higher median plasma PTX3 concentration than normal pregnant women (p<0.001 for all comparisons); 4) Similarly, patients with preterm PROM, with or without IAI had a higher median plasma PTX3 concentration than normal pregnant women (p<0.001 for both comparisons); and 5) Among patients with PTL and those with preterm PROM, IAI was not associated with significant changes in the median maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations.

Conclusions

The maternal plasma PTX3 concentration increases with advancing gestational age and is significantly elevated during labor at term and in the presence of spontaneous preterm labor or preterm PROM. These findings could not be explained by the presence of IAI, suggesting that the increased PTX3 concentration is part of the physiologic or pathologic activation of the pro-inflammatory response in the maternal circulation during the process of labor at term or preterm.

Keywords: preterm delivery, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, PPROM, pregnancy, amniocentesis, microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity, MIAC, cytokines, pattern recognition receptors

INTRODUCTION

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3), a soluble pattern recognition receptor (sPRR),1;2 plays an important role in the regulation of innate resistance to pathogens. Innate immune cells produce PTX3 in response to inflammatory signals and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) activation, acting as an acute phase response protein. Indeed, its concentration in normal conditions is low, but increases significantly and rapidly in plasma of patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, septic shock3 or other inflammatory and infectious conditions, correlating with the severity of the disease.4

During pregnancy, elevated concentrations of PTX3 have been reported in comparison to non-pregnant subjects;5;6 however, conflicting results exist regarding changes of PTX3 concentrations throughout gestation.5;6 In addition, several complications of pregnancy such as preeclampsia5–9 and preterm delivery10 have been reported to be associated with higher concentrations of PTX3 in the maternal circulation. Furthermore, our group demonstrated that PTX3 is a physiologic constituent of amniotic fluid, and its concentration is significantly elevated in the presence of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (IAI), suggesting that PTX3 may play a role in the innate immune response against microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity.11

Preterm parturition, with intact or ruptured membranes, is associated with a maternal systemic inflammatory response.12–19 Consistent with this view, Assi et al.10 reported higher maternal plasma concentrations of PTX3 in a pool of women with preterm labor (PTL) with intact membranes and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (preterm PROM) who delivered preterm before 34 weeks. Moreover, the authors concluded that intra-amniotic infection (based on the presence of clinical or histological chorioamnionitis) was not associated with significant changes in maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine if plasma PTX3 concentration changes in the maternal circulation in the presence of intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in women with PTL with intact membranes as well as those with preterm PROM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

A cross-sectional study was conducted by searching our clinical database and bank of biological samples, and included 446 women in the following groups: 1) non-pregnant (n= 40); 2) normal pregnancies in the first (n= 22), second (n= 22) or third (n= 71, including 50 at term not in labor) trimester of pregnancy; 3) uncomplicated term pregnancies with spontaneous labor (n=49); 4) women with PTL without IAI who delivered at term (n=49); 5) PTL without IAI who delivered preterm (n=26); 6) PTL with IAI (n=65); 7) preterm PROM with IAI (n=77); and 8) preterm PROM without IAI (n=25).

All participants provided written informed consent prior to the collection of maternal blood. The collection and utilization of blood samples for research purposes was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Sotero del Rio Hospital (Santiago, Chile), Wayne State University (Detroit, MI) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. Many of these samples have been used previously to study the biology of inflammation, hemostasis, and growth factor concentrations in uncomplicated pregnancies and those with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Definitions

Women were considered to have an uncomplicated pregnancy if they did not have any medical, obstetrical, or surgical complications, and delivered a normal neonate at term, which was appropriately grown for gestational age.20;21 Spontaneous PTL was defined as the presence of regular uterine contractions occurring at a frequency of at least two every 10 minutes associated with cervical change that required hospitalization before 37 completed weeks of gestation. Preterm PROM was diagnosed by sterile speculum examination confirmed by pooling of amniotic fluid in the vagina in association with nitrazine and ferning tests, before 37 weeks of gestation and prior to labor. Intra-amniotic infection was defined as a positive amniotic fluid culture for micro-organisms. Intra-amniotic inflammation was diagnosed by an amniotic fluid interleukin (IL)-6 concentration ≥ 2.6 ng/mL.22

Sample collection and determination of human PTX3 concentration in maternal plasma

Among patients with spontaneous PTL and intact membranes as well as those with preterm PROM, amniotic fluid samples were obtained by transabdominal amniocentesis performed for evaluation of microbial status of the amniotic cavity. Samples of amniotic fluid were transported to the laboratory in a sterile capped syringe and cultured for aerobic/anaerobic bacteria and genital mycoplasmas. An amniotic fluid white blood cell (WBC) count, glucose concentration and Gram-stain were also performed shortly after amniotic fluid collection as previously described.23–25 The results of these tests were used for clinical management. Amniotic fluid not required for clinical assessment was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −70°C until analysis. The amniotic fluid IL-6 concentrations were used only for research purposes. Maternal blood samples from patients with spontaneous PTL or preterm PROM were collected immediately before or after the amniocentesis into vacutainer tubes, centrifuged at 1300 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and obtained plasma was stored at −80°C until analysis.

Maternal plasma concentrations of PTX3 were determined by specific and sensitive enzyme-linked immunoassays (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO, USA). PTX3 assays were validated for use in human plasma in our laboratory prior to the conduction of this study. Immunoassays were carried out according to manufacturer’s recommendations. The calculated inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation for PTX3 in our laboratory were 2.7% and 3.4%, respectively. The sensitivity was calculated to be 0.12 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Since PTX3 concentrations in maternal plasma were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used for analyses. Comparisons between proportions were performed with the Fisher exact test. Kruskal-Wallis with post-hoc analysis and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables. Spearman’s rank correlation test was utilized to assess correlations between maternal plasma concentrations of PTX3 and gestational age. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations (ng/ml) and PTL or preterm PROM after adjusting for potential confounding factors including maternal age, (years), pre-pregnancy BMI (Kg/m2), smoking status and gestational age at blood sampling (weeks). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical package used was SPSS v.15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

Table I displays the demographic and clinical characteristics of women with a normal pregnancy, with spontaneous PTL and intact membrane and with preterm PROM. Patients with PTL, as well as those with preterm PROM, had a higher percentage of smokers and lower medians of pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational age at blood sampling, gestational age at delivery and neonatal birth weight than normal pregnant women.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with a normal pregnancy and patients with preterm labor and intact membranes (PTL) or preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (preterm PROM).

| Normal pregnancy (n=115) | Pa | PTL (n=140) | Preterm PROM (n=102) | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (yrs) † | 25 (21–29) | 0.001 | 22.5 (19–27) | 26 (22–31.25) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Ethnic origin | |||||

| African American | 80.4 (86) | 0.023 | 63.9 (85) | 67.7 (63) | NS |

| Caucasian | 11.2 (12) | NS | 9 (12) | 7.5 (7) | NS |

| Hispanic | 5.6 (6) | <0.001 | 26.3 (35) | 24.7 (23) | NS |

| Others | 2.8 (3) | NS | 0.7 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Smokers | 14.5 (16/110) | 0.01 | 27.5 (38/138) | 41.7 (40/96) | 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 24.6 (23.2–29) | 0.001 | 22.9 (20.4–26.7) | 23.6 (20.8–26.7) | 0.012 |

|

| |||||

| GA at blood sampling (wks) | 33.1 (22.6–39) | 0.004 | 30.7 (26–32.8) | 30 (26.8–31.8) | 0.003 |

|

| |||||

| GA at delivery (wks) | 39.3 (38.7–40.3) | <0.001 | 34 (27.8–38.1) | 30.9 (28.4–32.6) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Birthweight (grs) | 3330 (3110–3629) | <0.001 | 2240 (1022–2896) | 1570 (1157–1952) | <0.001 |

Values expressed as median (interquartile range) or percentage (number).

PTL: preterm labor; PROM: prelabor rupture of membranes; BMI: body mass index; GA, gestational age; NS: not significant.

Pa between normal pregnancy and preterm labor.

Pb between normal pregnancy and preterm PROM.

Pentraxin 3 concentrations in non-pregnant and normal pregnant women

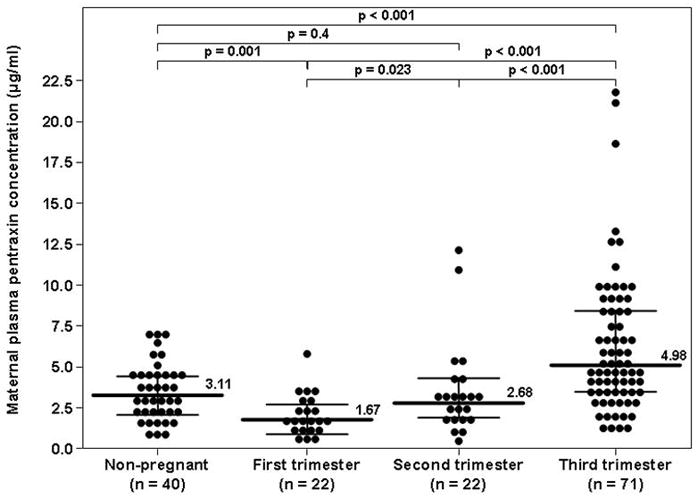

Pentraxin 3 was detected in all plasma samples included in this study. Maternal plasma PTX3 concentration significantly correlated with advancing gestational age (r= 0.62, p<0.001). Indeed, a significant difference was found in the PTX3 plasma concentrations in normal pregnancy among the three trimesters (first: 6–14 weeks, second: 14–28 weeks, and third trimester: 28–42 weeks; Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.001). The median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration in the third trimester was higher than that of the second trimester [4.98 ng/mL interquartile range (IQR) 3.3–8.38 vs 2.68 ng/mL, IQR 1.82–4.1; p<0.001] and that of the first trimester (1.67 ng/mL, IQR 0.95–2.48, p<0.001). Similarly, the median plasma PTX concentration was higher in the second than in the first trimester (p=0.023, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Plasma concentrations of PTX3 in non-pregnant and normal pregnant women in the first, second or third trimester of pregnancy.

The median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration in the third trimester was higher than that of the second trimester [4.98 ng/mL interquartile range (IQR) 3.3–8.38 vs 2.68 ng/mL, IQR 1.82–4.1; p<0.001] and that of the first trimester (1.67 ng/mL, IQR 0.95–2.48, p<0.001). Similarly, the median plasma PTX3 concentrations was higher in the second than in the first trimester (p=0.023). Compared to non-pregnant women (3.11 ng/mL IQR 1.94–4.49), the median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration in the first trimester was lower (p=0.001), in the second trimester comparable (p=0.4) and in the third trimester higher (p<0.001) than that of non-pregnant women.

There was no significant difference in the median plasma PTX3 concentration between non-pregnant women and those with a normal pregnancy when those in the latter group were pooled together (3.11 ng/mL IQR 1.94–4.49 vs. 2.61 ng/mL, IQR 1.76–4.05, respectively; p=0.24). Nevertheless, when the analysis was performed stratifying normal pregnant women by trimester of pregnancy, the median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration in the first trimester was lower (p=0.001), in the second trimester comparable (p=0.4) and in the third trimester higher (p<0.001) than that of non-pregnant women (Figure 1).

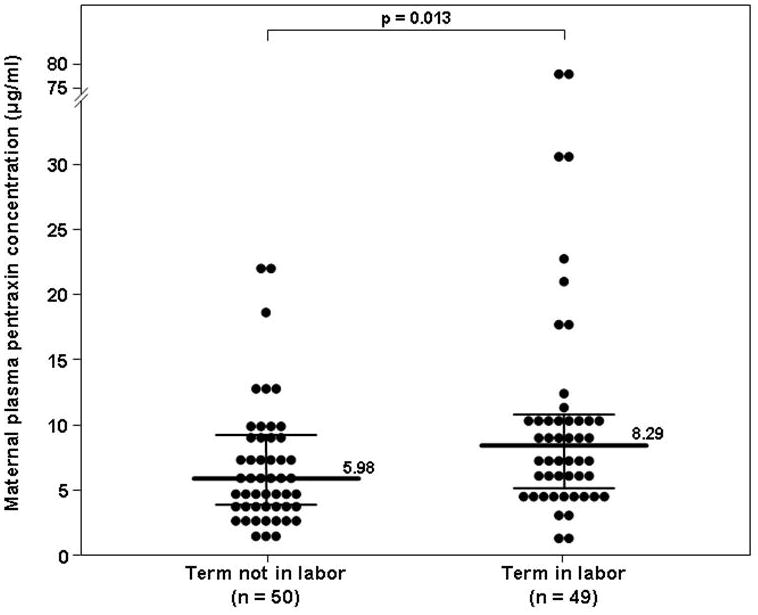

Among women at term, those with spontaneous labor had a higher median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration than those not in labor (8.29 ng/mL, IQR 5.1–10.5 vs. 5.98 ng/mL, IQR 3.95–9.05, p=0.013) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Maternal plasma concentration of PTX3 in pregnant women at term with and without spontaneous labor.

The median maternal plasma concentration of PTX3 was higher in women at term with spontaneous labor than in those not in labor (8.29 ng/mL, IQR 5.1–10.5 vs. 5.98 ng/mL, IQR 3.95–9.05, p=0.013)

Pentraxin 3 concentrations in patients with PTL with intact membranes or with preterm PROM

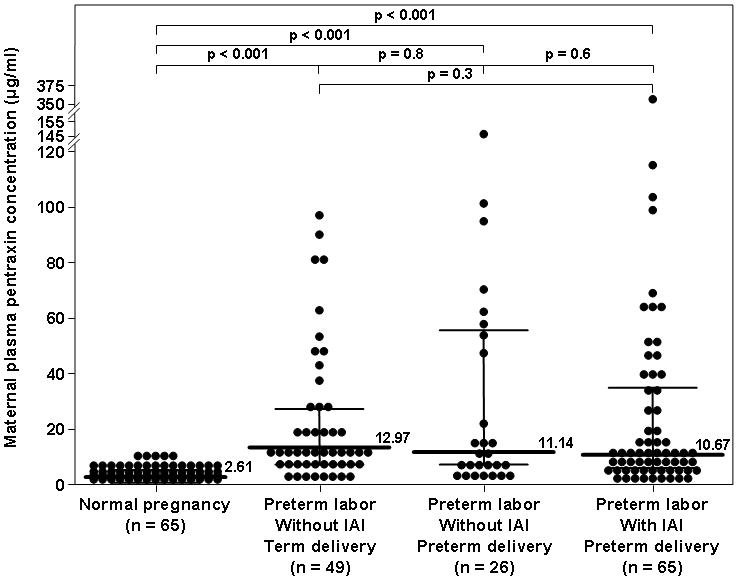

The median maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations did not differ significantly between patients with PTL who delivered preterm either with IAI (10.67 ng/mL, IQR 5.99–34.12) or without IAI (11.14 ng/mL, IQR 6.12–54.62), as well as those with an episode of PTL who subsequently delivered at term (12.97 ng/mL, IQR 7.49–24.24) (Kruskal-Wallis, p=0.6), but it was significantly higher than that of women with a normal pregnancy (2.61 ng/mL, IQR 1.76–4.05; p<0.001 for all comparisons, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of the median maternal plasma concentration of PTX3 of patients with spontaneous preterm labor (PTL) with intact membranes and those with a normal pregnancy.

The median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration was higher in women with PTL who delivered preterm, either with (10.67 ng/mL, IQR 5.99–34.12) or without IAI (11.14 ng/mL, IQR 6.12–54.62), as well as in those with an episode of PTL who subsequently delivered at term (12.97 ng/mL, IQR 7.49–24.24) than that of women with a normal pregnancy (2.61 ng/mL, IQR 1.76–4.05; p<0.001 for all comparisons). Among patients with PTL, the median plasma PTX3 concentrations did not differ significantly between the three subgroups (Kruskal-Wallis, p=0.6).

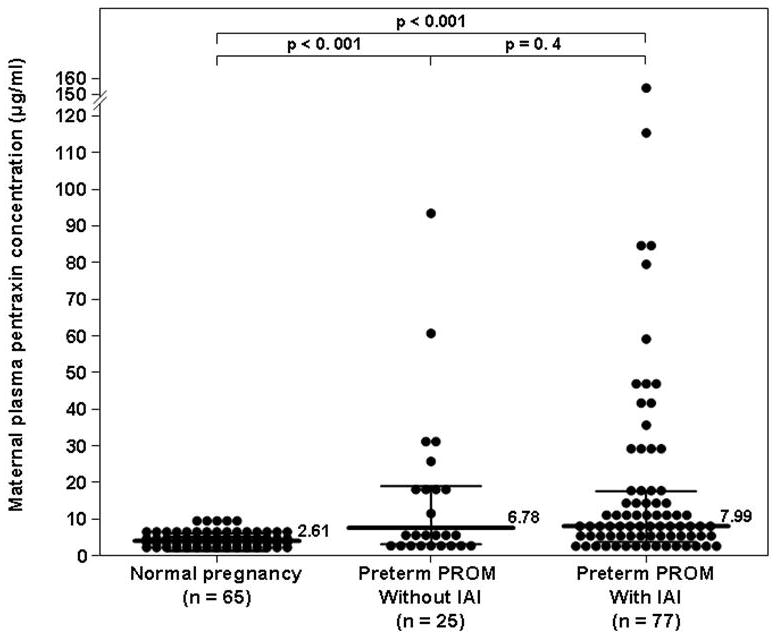

Patients with preterm PROM, either with IAI (7.99 ng/mL, IQR 4.28–16.78) or without IAI (6.78 ng/mL, IQR 3.2–17.42; p<0.001), had a higher median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration than women with a normal pregnancy (2.61 ng/mL, IQR 1.76–4.05; p<0.001 for both comparisons, Figure 4). Among patients with preterm PROM, there was no difference in the median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration between those with and without IAI (p=0.4, Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of the median maternal plasma concentration of PTX3 of patients with prelabor premature rupture of membranes (preterm PROM) and those with a normal pregnancy.

The median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration was higher in patients with preterm PROM, either with IAI (7.99 ng/mL vs. 2.61 ng/mL; p<0.001) or without IAI (6.78 ng/mL; p<0.001), than those with a normal pregnancy. Among patients with preterm PROM, there was no difference in the median maternal plasma PTX3 concentration between those with and without IAI (p=0.4).

In a multivariable logistic regression model, maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations (ng/ml) were independently and significantly associated with PTL (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.17–1.45, p<0.001) and preterm PROM (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06–1.28, p=0.002) after adjusting for potential confounding factors including maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking status and gestational age at blood sampling.

DISCUSSION

Principal findings of the study

1) Maternal plasma concentrations of PTX3 increase with advancing gestational age; 2) spontaneous preterm and term labor are associated with significant changes in the median maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations; and 3) intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation is not associated with a significant change in PTX3 concentrations in maternal circulation.

Pentraxin 3 and the immune response

Pentraxins, a family of evolutionarily conserved pattern recognition proteins, are an essential component of the innate immune response characterized by a distinctive cyclic pentameric structure.1;26 Based on their primary structure, pentraxins are divided into short and long pentraxins; both groups share the same C-terminal pentraxin-like domain, but the long pentraxins differ by the presence of a unique and unrelated long N-terminal domain.1;4;26–35 C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid P-component (SAP), acute-phase proteins produced in the liver in response to inflammatory mediators, are the classical short pentraxins.

Pentraxin 3, also called TNF stimulated gene 14 (TSG14),28;30;34;36–38 is the prototype of the long pentraxins family and was the first long pentraxin to be identified.28;30;36 Similarly to CRP, PTX3 performs as an acute phase response protein. Its concentration, which is low in normal conditions (≤ 2 ng/ml), increases rapidly (peak at 6–8 hours) and dramatically (200–800 ng/ml) during inflammatory conditions such as endotoxic shock, infections, sepsis, autoimmune diseases, and degenerative disorders.3;39;40 In response to primary inflammatory signals [(e.g. IL-1β, TNF-α, TLR engagement or after stimulation with microbial components such as lypopolysaccharide 1;4;41], PTX3 is rapidly produced and released by several cell types including dendritic cells,42–44 mononuclear phagocytes,45 fibroblasts,46 as well as endothelial28;30;47 and epithelial cells.48

Pentraxin 3 during normal pregnancy and labor at term

Previous studies demonstrated that PTX3 concentration in maternal circulation is significantly higher during normal pregnancy than in the non-pregnant state.5;6 However, conflicting results have been reported regarding the changes in maternal circulating PTX3 concentration throughout gestation.5;6 While Rovere-Querini et al.5 reported a positive correlation with advancing gestational age, Cetin et al.6 found no change in maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations during pregnancy. In this study, we have demonstrated that the reported increase in PTX3 concentration in normal pregnant compared to non-pregnant women is mainly due to higher concentrations in the third trimester of pregnancy, and that the maternal plasma concentrations of PTX3 in the first trimester were lower than, and those in the second trimester similar to, than that of those from non-pregnant women. These findings, together with the significant correlation between maternal plasma PTX3 concentration and gestational age, are in agreement with the report by Rovere-Querini et al.5 and further supports the notion that normal pregnancy is a pro-inflammatory state characterized by physiologic activation of the innate limb of the immune response.49–58

Similarly, the finding of a significant increase in maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations during labor at term is in agreement with the report by Rovere-Querini et al.5 and support the view that spontaneous labor at term is an inflammatory process.12;59–75 Indeed, labor at term is accompanied by increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines12;61–66;71;72 and chemokines12;65;67;70;71;73;75 and an association between term parturition and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the cervix,59;60;72 myometrium,68;72 and chorioamniotic membranes68;69 has been demonstrated.

Pentraxin 3 in preterm labor with intact membranes and in preterm PROM

The findings reported herein demonstrated that patients with PTL and those with preterm PROM had higher maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations than normal pregnant women, regardless of the presence or absence of IAI. In addition, we have demonstrated that the increased concentration of PTX3 in the maternal circulation is not confined to patients who delivered preterm, but also to those with an episode of PTL that subsequently delivered at term.

Recently, Assi et al.10 reported significantly higher maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations in a pool of 46 patients with PTL or preterm PROM who delivered before 34 weeks, than that of normal pregnant women. The authors did not find differences in the concentrations of PTX3 between patients with and without intra-amniotic infection,10 although this diagnosis was based on the presence of clinical and/or histologic chorioamnionitis, instead on the results of amniotic fluid cultures and IL-6 concentrations as in the present study. Thus, IAI does not appear to explain the increased maternal plasma PTX3 concentrations demonstrated during an episode of spontaneous PTL or in preterm PROM. Taken together, these findings suggest that elevated PTX3 concentrations in maternal plasma of women with PTL or preterm PROM may be related to the mechanisms involved in the process of labor itself and not to intra-amniotic infection.

Systemic maternal inflammation has been implicated in the pathophysiology of preterm labor and preterm PROM;76–78 it has been shown that preterm parturition with intact76 or ruptured membranes77 is associated with phenotypic and metabolic changes in maternal monocytes and granulocytes, consistent with the presence of intravascular maternal inflammation. One can speculate that the increased concentration of PTX3 in the maternal circulation of patients with an episode of PTL or preterm PROM is a manifestation of the pathologic systemic inflammatory process associated with these pregnancy complications and that is independent of the microbial status of the amniotic cavity. In support of this view is the observation of Chevillard at al.79 who reported that in myometrial smooth muscle cells induced by IL-1β, the PTX3 gene has been found to be among the up-regulated inflammatory genes (6-fold change), suggesting a link between the inflammatory response and the process of labor.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the maternal plasma PTX3 concentration increases with advancing gestational age and is significantly elevated during labor at term, as well as in the presence of spontaneous PTL with intact membranes or preterm PROM. However, these findings can not be explained by the presence of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation, suggesting that increased maternal plasma PTX3 concentration is part of the physiologic or pathologic activation of the inflammatory response in maternal circulation during the process of term or preterm labor.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

Reference List

- 1.Garlanda C, Bottazzi B, Bastone A, Mantovani A. Pentraxins at the crossroads between innate immunity, inflammation, matrix deposition, and female fertility. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:337–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottazzi B, Garlanda C, Cotena A, Moalli F, Jaillon S, Deban L, et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a prototypic humoral pattern recognition receptor: interplay with cellular innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller B, Peri G, Doni A, Torri V, Landmann R, Bottazzi B, et al. Circulating levels of the long pentraxin PTX3 correlate with severity of infection in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1404–07. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottazzi B, Garlanda C, Salvatori G, Jeannin P, Manfredi A, Mantovani A. Pentraxins as a key component of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rovere-Querini P, Antonacci S, Dell’Antonio G, Angeli A, Almirante G, Cin ED, et al. Plasma and tissue expression of the long pentraxin 3 during normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:148–55. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224607.46622.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cetin I, Cozzi V, Pasqualini F, Nebuloni M, Garlanda C, Vago L, et al. Elevated maternal levels of the long pentraxin 3 (PTX3) in preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1347–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rovere-Querini P, Castiglioni MT, Sabbadini MG, Manfredi AA. Signals of cell death and tissue turnover during physiological pregnancy, pre-eclampsia, and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2007;40:290–94. doi: 10.1080/08916930701358834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akolekar R, Casagrandi D, Livanos P, Tetteh A, Nicolaides KH. Maternal plasma pentraxin 3 at 11 to 13 weeks of gestation in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2009 doi: 10.1002/pd.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cetin I, Cozzi V, Papageorghiou AT, Maina V, Montanelli A, Garlanda C, et al. First trimester PTX3 levels in women who subsequently develop preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:846–49. doi: 10.1080/00016340902971441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assi F, Fruscio R, Bonardi C, Ghidini A, Allavena P, Mantovani A, et al. Pentraxin 3 in plasma and vaginal fluid in women with preterm delivery. BJOG. 2007;114:143–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruciani L, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazaki-Tovi S, Mittal P, Ogge’ G, Gotsch F, Erez O, Kim SK, Zhong D, Pacora P, Lamont RF, Yeo L, Hassan SS, Di Renzo GC. Pentraxin 3 in Amniotic Fluid: A Novel Association with Intra–amniotic Infection and Inflammation. Jounal of Perinatal Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.141. Ref Type: In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel LA, Nien JK. Inflammation in preterm and term labour and delivery. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:317–26. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs RS, Romero R, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA, Sweet RL. A review of premature birth and subclinical infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1515–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91628-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–07. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Berry SM. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minkoff H. Prematurity: infection as an etiologic factor. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62:137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero R, Mazor M. Infection and preterm labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1988;31:553–84. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero R, Mazor M, Wu YK, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E, Mitchell MD, et al. Infection in the pathogenesis of preterm labor. Semin Perinatol. 1988;12:262–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero R, Gomez R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Edwin SS, et al. A fetal systemic inflammatory response is followed by the spontaneous onset of preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:186–93. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–68. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez RP, Gomez RM, Castro RS, Nien JK, Merino PO, Etchegaray AB, et al. A national birth weight distribution curve according to gestational age in Chile from 1993 to 2000. Rev Med Chil. 2004;132:1155–65. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872004001000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon BH, Romero R, Moon JB, Shim SS, Kim M, Kim G, et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1130–36. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero R, Emamian M, Quintero R, Wan M, Hobbins JC, Mazor M, et al. The value and limitations of the Gram stain examination in the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:114–19. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero R, Jimenez C, Lohda AK, Nores J, Hanaoka S, Avila C, et al. Amniotic fluid glucose concentration: a rapid and simple method for the detection of intraamniotic infection in preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:968–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91106-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero R, Quintero R, Nores J, Avila C, Mazor M, Hanaoka S, et al. Amniotic fluid white blood cell count: a rapid and simple test to diagnose microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and predict preterm delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991;165:821–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90423-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gewurz H, Zhang XH, Lint TF. Structure and function of the pentraxins. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:54–64. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coe JE, Margossian SS, Slayter HS, Sogn JA. Hamster female protein. A new Pentraxin structurally and functionally similar to C-reactive protein and amyloid P component. J Exp Med. 1981;153:977–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.4.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breviario F, d’Aniello EM, Golay J, Peri G, Bottazzi B, Bairoch A, et al. Interleukin-1-inducible genes in endothelial cells. Cloning of a new gene related to C-reactive protein and serum amyloid P component. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22190–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pepys MB, Baltz ML. Acute phase proteins with special reference to C-reactive protein and related proteins (pentaxins) and serum amyloid A protein. Adv Immunol. 1983;34:141–212. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60379-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee GW, Lee TH, Vilcek J. TSG-14, a tumor necrosis factor- and IL-1-inducible protein, is a novel member of the pentaxin family of acute phase proteins. J Immunol. 1993;150:1804–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley J, White HE, O’Hara BP, Oliva G, Srinivasan N, Tickle IJ, et al. Structure of pentameric human serum amyloid P component. Nature. 1994;367:338–45. doi: 10.1038/367338a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szalai AJ, Agrawal A, Greenhough TJ, Volanakis JE. C-reactive protein: structural biology and host defense function. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:265–70. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Bottazzi B. Pentraxin 3, a non-redundant soluble pattern recognition receptor involved in innate immunity. Vaccine. 2003;21 (Suppl 2):S43–S47. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI18921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee GW, Goodman AR, Lee TH, Vilcek J. Relationship of TSG-14 protein to the pentraxin family of major acute phase proteins. J Immunol. 1994;153:3700–07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan N, White HE, Emsley J, Wood SP, Pepys MB, Blundell TL. Comparative analyses of pentraxins: implications for protomer assembly and ligand binding. Structure. 1994;2:1017–27. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(94)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bottazzi B, Vouret-Craviari V, Bastone A, De GL, Matteucci C, Peri G, et al. Multimer formation and ligand recognition by the long pentraxin PTX3. Similarities and differences with the short pentraxins C-reactive protein and serum amyloid P component. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32817–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peri G, Introna M, Corradi D, Iacuitti G, Signorini S, Avanzini F, et al. PTX3, A prototypical long pentraxin, is an early indicator of acute myocardial infarction in humans. Circulation. 2000;102:636–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Doni A, Bottazzi B. Pentraxins in innate immunity: from C-reactive protein to the long pentraxin PTX3. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeannin P, Bottazzi B, Sironi M, Doni A, Rusnati M, Presta M, et al. Complexity and complementarity of outer membrane protein A recognition by cellular and humoral innate immunity receptors. Immunity. 2005;22:551–60. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doni A, Peri G, Chieppa M, Allavena P, Pasqualini F, Vago L, et al. Production of the soluble pattern recognition receptor PTX3 by myeloid, but not plasmacytoid, dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2886–93. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doni A, Michela M, Bottazzi B, Peri G, Valentino S, Polentarutti N, et al. Regulation of PTX3, a key component of humoral innate immunity in human dendritic cells: stimulation by IL-10 and inhibition by IFN-gamma. Jveukoc Biol. 2006;79:797–802. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0905493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perrier P, Martinez FO, Locati M, Bianchi G, Nebuloni M, Vago G, et al. Distinct transcriptional programs activated by interleukin-10 with or without lipopolysaccharide in dendritic cells: induction of the B cell-activating chemokine, CXC chemokine ligand 13. J Immunol. 2004;172:7031–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alles VV, Bottazzi B, Peri G, Golay J, Introna M, Mantovani A. Inducible expression of PTX3, a new member of the pentraxin family, in human mononuclear phagocytes. Blood. 1994;84:3483–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semov A, Semova N, Lacelle C, Marcotte R, Petroulakis E, Proestou G, et al. Alterations in TNF- and IL-related gene expression in space-flown WI38 human fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2002;16:899–901. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-1002fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Presta M, Camozzi M, Salvatori G, Rusnati M. Role of the soluble pattern recognition receptor PTX3 in vascular biology. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:723–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nauta AJ, de HS, Bottazzi B, Mantovani A, Borrias MC, Aten J, et al. Human renal epithelial cells produce the long pentraxin PTX3. Kidney Int. 2005;67:543–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.EFRATI P, PRESENTEY B, Margarlith M, ROZENSZAJN L. Leukocytes of Normal Pregnant Women. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;23:429–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stirling Y, Woolf L, North WR, Seghatchian MJ, Meade TW. Haemostasis in normal pregnancy. Thromb Haemost. 1984;52:176–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hopkinson ND, Powell RJ. Classical complement activation induced by pregnancy: Implications for management of connective tissue diseases. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:66–67. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Comeglio P, Fedi S, Liotta AA, Cellai AP, Chiarantini E, Prisco D, et al. Blood clotting activation during normal pregnancy. Thromb Res. 1996;84:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sacks GP, Studena K, Sargent K, Redman CW. Normal pregnancy and preeclampsia both produce inflammatory changes in peripheral blood leukocytes akin to those of sepsis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naccasha N, Gervasi MT, Chaiworapongsa T, Berman S, Yoon BH, Maymon E, et al. Phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of monocytes and granulocytes in normal pregnancy and maternal infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1118–23. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luppi P, Haluszczak C, Trucco M, DeLoia JA. Normal pregnancy is associated with peripheral leukocyte activation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002;47:72–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.1o041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luppi P, Haluszczak C, Betters D, Richard CA, Trucco M, DeLoia JA. Monocytes are progressively activated in the circulation of pregnant women. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:874–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sacks GP, Redman CW, Sargent IL. Monocytes are primed to produce the Th1 type cytokine IL-12 in normal human pregnancy: an intracellular flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:490–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richani K, Soto E, Romero R, Espinoza J, Chaiworapongsa T, Nien JK, et al. Normal pregnancy is characterized by systemic activation of the complement system. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17:239–45. doi: 10.1080/14767050500072722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Junqueira LC, Zugaib M, Montes GS, Toledo OM, Krisztan RM, Shigihara KM. Morphologic and histochemical evidence for the occurrence of collagenolysis and for the role of neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes during cervical dilation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:273–81. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liggins GC. Cervical ripening as an inflammatory reaction. In: Ellwood DA, Anderson ABM, editors. The Cervix in Pregnancy and Labour: Clinical and Biochemical Investigations. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1981. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romero R, Brody DT, Oyarzun E, Mazor M, Wu YK, Hobbins JC, et al. Infection and labor. III. Interleukin-1: a signal for the onset of parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1117–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romero R, Ceska M, Avila C, Mazor M, Behnke E, Lindley I. Neutrophil attractant/activating peptide-1/interleukin-8 in term and preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:813–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90422-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romero R, Mazor M, Sepulveda W, Avila C, Copeland D, Williams J. Tumor necrosis factor in preterm and term labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1576–87. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91636-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Opsjln SL, Wathen NC, Tingulstad S, Wiedswang G, Sundan A, Waage A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:397–404. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saito S, Kasahara T, Kato Y, Ishihara Y, Ichijo M. Elevation of amniotic fluid interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8 and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in term and preterm parturition. Cytokine. 1993;5:81–88. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(93)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osmers RG, Blaser J, Kuhn W, Tschesche H. Interleukin-8 synthesis and the onset of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:223–29. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)93704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen J, Ghezzi F, Romero R, Ghidini A, Mazor M, Tolosa JE, et al. GRO alpha in the fetomaternal and amniotic fluid compartments during pregnancy and parturition. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1996;35:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomson AJ, Telfer JF, Young A, Campbell S, Stewart CJ, Cameron IT, et al. Leukocytes infiltrate the myometrium during human parturition: further evidence that labour is an inflammatory process. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keski-Nisula L, Aalto ML, Katila ML, Kirkinen P. Intrauterine inflammation at term: a histopathologic study. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:841–46. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.8449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Esplin MS, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Edwin S, Gomez R, et al. Amniotic fluid levels of immunoreactive monocyte chemotactic protein-1 increase during term parturition. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;14:51–56. doi: 10.1080/jmf.14.1.51.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Keelan JA, Blumenstein M, Helliwell RJ, Sato TA, Marvin KW, Mitchell MD. Cytokines, prostaglandins and parturition--a review. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl A):S33–S46. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osman I, Young A, Ledingham MA, Thomson AJ, Jordan F, Greer IA, et al. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:41–45. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Esplin MS, Peltier MR, Hamblin S, Smith S, Fausett MB, Dildy GA, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression is increased in human gestational tissues during term and preterm labor. Placenta. 2005;26:661–71. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haddad R, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Mazor M, et al. Human spontaneous labor without histologic chorioamnionitis is characterized by an acute inflammation gene expression signature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:394–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Lye SJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL-2) integrates mechanical and endocrine signals that mediate term and preterm labor. J Immunol. 2008;181:1470–79. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gervasi MT, Chaiworapongsa T, Naccasha N, Blackwell S, Yoon BH, Maymon E, et al. Phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of maternal monocytes and granulocytes in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1124–29. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gervasi MT, Chaiworapongsa T, Naccasha N, Pacora P, Berman S, Maymon E, et al. Maternal intravascular inflammation in preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:171–75. doi: 10.1080/jmf.11.3.171.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Romero R, Gotsch F, Pineles B, Kusanovic JP. Inflammation in pregnancy: its roles in reproductive physiology, obstetrical complications, and fetal injury. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S194–S202. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chevillard G, Derjuga A, Devost D, Zingg HH, Blank V. Identification of interleukin-1beta regulated genes in uterine smooth muscle cells. Reproduction. 2007;134:811–22. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]