Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to provide an overview about the existence and types of discounts and rebates granted to public payers by the pharmaceutical industry in European countries.

Methods: Data were collected via a questionnaire in spring 2011. Officials from public authorities for pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement represented in the PPRI (Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information) network provided the information and reviewed the compilation.

Results: Information is available from 31 European countries. Discounts and rebates granted to public payers by pharmaceutical industry were reported for 25 European countries. Such discounts exist both in the in- and out-patient sectors in 21 countries and in the in-patient sector only in four countries. Six countries reported not having any regulations or agreements regarding the discounts and rebates granted by industry. The most common discounts and rebates are price reductions and refunds linked to sales volume but types such as in-kind support, price-volume and risk-sharing agreements are also in place. A mix of various types of discounts and rebates is common. Many of these arrangements are confidential. Differences regarding types, the organizational and legal framework, validity and frequency of updates and the amount of the discounts and rebates granted exist among the surveyed countries.

Conclusions: In Europe, discounts and rebates on medicines granted by pharmaceutical industry to public payers are common tools to contain public pharmaceutical expenditure. They appear to be used as a complimentary measure when price regulation does not achieve the desired results and in the few European countries with no or limited price regulation. The confidential character of many of these arrangements impedes transparency and may lead to a distortion of medicines prices. An analysis of the impact on these measures is recommended.

Keywords: medicines, Europe, discount, rebate, cost-containment, policy measure, payer, reimbursement, tendering

Introduction

Governments’ medicines policies aim to provide to their population safe, affordable and effective medicines, at least with regard to essential medicines [1-4]. This objective is compromised by financial restraints which all European, including high-income, countries are facing [5-7]. The most commonly applied policy measures in response to the global financial crisis are price cuts, increase in co-payments, value-added tax (VAT) rates on medicines and in the distribution add-ons [8]. Such measures are usually implemented by executive order or regulation rather swiftly. During the last years, however, additional policies have been implemented in some countries: The Netherlands introduced the so-called preferential pricing policy which is a tendering system in the out-patient sector [9, 10]. In Germany rebates on medicines prices are negotiated between sickness funds and manufacturers [11, 12], and tendering-like models in the pricing and/or reimbursement process in the out-patient sector are also in place in other European countries (e.g. Denmark, Hungary, Slovakia) [13-15]. The Belgian model of such tendering by the sickness funds, the “Kiwi model”, proved not successful and is no longer being applied [16, 17]. Further examples of new approaches are risk-sharing, cost-sharing and further forms of managed entry agreements which can be described as formal arrangements between public payers and pharmaceutical companies with the aim of sharing the financial risk due to uncertainty surrounding the introduction of new technologies [18-20]. All these rather new policies have in common that they aim to manage, often on a confidential agreement level, uncertainty and that pharmaceutical companies get involved in sharing financial responsibility. Price-volume agreements, refunds by the pharmaceutical industry and further discounts and rebates granted by companies to public payers are further policy options with the same goal.

Literature is primarily available on discounts and rebates in the distribution chain, in particular regarding generic medicines [21-25]. But there is little published evidence about regulations and agreements on discounts and rebates granted by pharmaceutical companies to public payers even though personal communication with representatives of authorities as well as of the pharmaceutical industry have suggested that discounts, rebates, refunds and similar forms are applied in some European countries.

We undertook this study to order to learn more about the existence of these measures, also in smaller countries which are often excluded from research, and to get a better understanding about their relevance across Europe. We sought to survey and provide a mapping of discounts and rebates which pharmaceutical companies grant on reimbursable medicines to public payers in European countries. Further discounts and rebates (e.g. along the distribution chain) were not in the scope of the investigation.

Methods

The mapping exercise of manufacturer discounts and rebates in European countries was primarily done via a questionnaire replied by public authorities for pricing and reimbursement.

Definitions and scope

The investigation addressed discounts and rebates granted by pharmaceutical companies to public payers. Discounts and rebates on all medicines in the reimbursed market (so-called reimbursable medicines, i.e. medicines covered primarily by public funds), both original products and generics, were included. Both the out-patient and in-patient sectors were in the scope of the survey. Any discounts and rebates granted to wholesalers, pharmacists, other companies such as distributors and patients/consumers were excluded. Public payers, which are also called “third party payers”, are, usually public, institutions which cover health or medical expenses on behalf of beneficiaries or recipients. Typically, third party payers in European countries are either National Health Services (NHS, e.g. in Italy, Portugal, Spain, UK – “Beveridge systems” funded by the state) or Social Health Insurance institutions (e.g. Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and in all Central and Eastern European countries; “Bismark systems”) [26, 27].

Whereas discounts are defined as “price reductions granted to specified purchasers under specific conditions prior to purchase”, rebates contain an ex-post component since they are “payments made to the purchaser after the transaction has occurred” [28]. Being mindful of additional types of discounts and rebates, we listed in the questionnaire some examples (e.g., in-kind support including “cost-free” donations, bundling procedures which offer a combination of different types of products at a reduced price). We explicitly invited the respondents to include further types which they would subsume under “discounts and rebates”.

Sample group

Information was collected from the public authorities for pricing and reimbursement in the European countries, in particular in the European Union (EU) zone. We aimed at achieving a high, possibly full, coverage of the 27 EU Member States, and we were pleased that further non-EU countries also contributed to the exercise. Respondents to the questionnaire were officials and staff of public authorities represented in the PPRI (Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information) network. PPRI is a networking and information-sharing initiative on pharmaceutical policies from a public health perspective which emerged from a European Commission co-funded project under the same name [29, 30]. At the time of the survey, PPRI consisted of more than 60 institutions, mainly Medicines Agencies, Ministries of Health and Social Insurance institutions, from 38 countries, including all 27 EU Member States, eight other European countries and three non-European countries, plus European and international institutions (European Commission services and agencies, OECD, WHO and World Bank)i.

Survey instrument

We developed a draft questionnaire and piloted it with the third party payer in Austria, the Main Association of Austrian Social Security Institutions (MASSI), in February 2011. Following the pilot, we revised the questionnaire.

The finalized questionnaire consisted of a total of ten questions which explored:

the existence of discounts and rebates to public payers,

their types (e.g. price reductions, refunds, bundling, etc.), their design (e.g. linked to sales of a single product or the full product range of a company, based on the number of patients treated) and extent,

the legal/contractual framework (e.g. law/regulation, agreement, tendering, individual negotiations) and the parties involved, and

the frequency of updates.

Most questions provided several options and additionally allowed for open-ended answers. In order to ensure a high commitment of the respondents and a common understanding, the questionnaire started with a rationale for the survey and definitions of key terms.

Data collection and validation

On 25 February 2011 we sent the revised questionnaire by e-mail to the members of the PPRI network. The respondents were requested to answer the questionnaire electronically within two weeks which is the usual time for queries within the PPRI network. Furthermore, they were encouraged to forward the questionnaire to competent persons and bodies in case they were not in the position to provide answers.

We received completed questionnaires from 14 countries within the time limit. Responses from 12 additional countries arrived after reminders per e-mail or telephone. These 26 country responses came from 20 EU Member States and, additionally, from six non-EU countries. For a few missing countries, we considered information, where available, from the PPRI Pharma Profiles [31], the national PHIS Hospital Pharma Reports [32] and the PHIS Hospital Pharma Report [33].

Data were compiled at the end of March 2011, and the summary of results was shared with the PPRI network through an Intranet platform. The compilation was presented to the network members during a PPRI network meeting in Madrid in February 2012.

At the beginning of May 2012, the respondents had another opportunity to check the information from their country (as of 2011) when we sent the draft article to the PPRI network for information, approval and validation. Following the meeting and the sharing of the draft article, previously compiled information was revised and expanded; and we got responses to the questionnaire from four further countries.

The mapping comprises responses from 31 of the 33 surveyed countries (all 27 EU Member States except Poland and Romania; plus Albania, Croatia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey).

Confidentiality issues and approval

We are aware that the issue of discounts and rebates is a sensitive one and, at least partially, subject to confidentiality clauses in some countries.

We informed the respondents about the intention to publish the results in a scientific article during the PPRI network meeting in February 2012, and we shared the draft article for validation and approval.

Results

The survey showed that manufacturer discounts, rebates and similar types granted to public payers do play a role in most European countries.

Mapping by countries and sectors

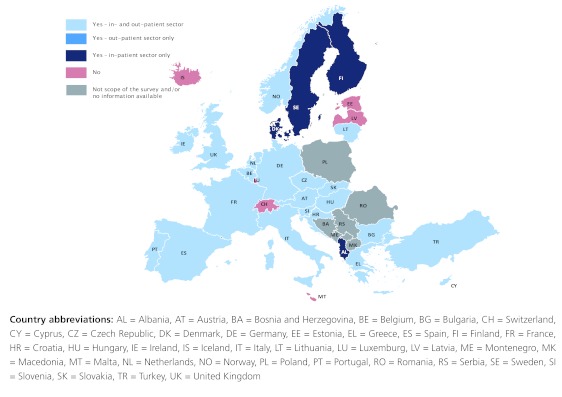

In 25 European countries such discounts and rebates were reported, in both the in- and out-patient sectors in 21 countries and in the in-patient sector only in four countries (Figure 1).

The most common form regarding the sectors is the existence of the discounts and rebates in both the out-patient and in-patient sectors. In four, particularly Northern European, countries (Albania, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) discounts are not applied in the out-patient sector but only in the in-patient sector. Six countries (Estonia, Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta and Switzerland) reported that no form of discounts from pharmaceutical companies to public payers existed.

Figure 1. European mapping of discounts and rebates granted to public payers, 2011.

Types of discounts and rebates

The most common form of discounts and rebates applied in European countries is price reductions. The ex-factory prices (e.g. for reimbursed medicines in Austria) or the pharmacy purchase prices (e.g. for all medicines in Cyprus) are regulated by law and price reductions are applied to this respective price type. 21 European countries reported price reductions: 16 countries both in the out-patient and in-patient sectors, three in the in-patient sector only and two in the out-patient sector (Table 1).

Refunds granted by pharmaceutical companies linked to sales volume are also common measures applied, they rank second. Eleven countries reported receiving rebates, typically in both the out-patient and in-patient sectors (seven countries; four countries in the out-patient sector only). In-kind support (e.g. buy two and get one for free) was mentioned by seven countries, mainly applied in the in-patient sector, and thus this type ranks third.

The questionnaire also indicated “global reductions of payments to pharmaceutical companies” and “bundling” which were reported by four countries (Austria, Germany, Hungary and Slovenia – all out-patient sector only) and four countries (Croatia, Finland, Portugal, Slovenia – mainly in-patient) respectively.

The respondents could freely list additional types of discounts and rebates granted to public payers, which they used to indicate, among others, price-volume agreements and different types of risk-sharing agreements.

As shown in Table 1, combinations of different types are applied. In the out-patient sector price reductions and refunds to public payers are common combinations and are often linked to the sales volume of a single product or the total volume of sales of all products of a specific company.

Table 1. Types of discounts and rebates on medicines granted to public payers in 31 European countries, 2011

| Types | Countries |

| Reduction of prices (the controlled price type: i. e. ex-factory price or wholesale/retail prices) | Austria (oi), Bulgaria (oi), Croatia (oi), Cyprus (oi), Czech Republic (oi), Denmark (i), Finland (i), France (oi), Germany (oi), Greece (oi), Hungary (oi), Ireland (i), Italy (o1i), Netherlands (oi), Norway (oi), Portugal (o), Slovakia (oi), Slovenia (o), Spain (oi), Turkey (oi), United Kingdom (o2,i) |

| (Global) reductions of payments to pharmaceutical companies | Austria (o), Germany (o),Hungary (o), Slovenia (o) |

| In-kind support | Austria (i), Croatia (oi), Cyprus (oi), Finland (i),), Netherlands (i), Portugal (i), United Kingdom (i) |

| Bundling (offering several products for sale as one combined product) | Croatia (oi), Finland (i), Portugal (i), Slovenia (o) |

| Refunds by pharmaceutical companies back to public payers depending on the sales volume of medicines | Austria (oi), Belgium (oi), Croatia (oi), France (oi), Germany (o), Ireland (oi), Italy (o), Portugal (oi), Slovenia (o), Spain (oi), United Kingdom1 (o) |

| Other forms:3 | |

| Price-volume agreements | France (o), Germany (o), Hungary (oi), Latvia (oi), Lithuania (oi), Slovenia (o) |

| Risk-sharing agreements | Germany (o), Italy (o), Slovenia (o), United Kingdom4 (i) |

| shared risk of potential overspending of a pre-defined target | France (oi), Croatia (oi), Hungary (oi), Italy (o), Slovenia (o) |

| cross product schemes5 | Croatia (oi), Slovenia (o) |

| reduction of wholesale mark-ups (if pharmaceutical company provides wholesale as well) | Slovakia (oi) |

| all types of discounts allowed (not regulated) | Slovenia (o) |

| not specified | Sweden (i) |

1 Companies could choose between a price cuts or payback mechanism (based on Law as July 2006).

2 Companies could choose between price reduction, price modulation and refund.

3 Open-ended question: information as provided by respondents whose completeness cannot be guaranteed.

4 Dose cap schemes, single fixed price, response scheme.

5 harmaceutical companies submit binding offers when they apply for inclusion in the reimbursement list. The application can be connected to a parallel proposal for reduction of a price of a medicine already included in the reimbursement list.

Coverage: All 27 European Union Member States except Poland and Romania plus Albania, Croatia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey. Slovenia – only information on the out-patient sector (discounts and rebates also applied in the in-patient sector).

Abbreviations: o = out-patient sector, i = in-patient sector, oi = out- and in-patient sector

Legal and organisational framework

Discounts and rebates in the out-patient sector are often the result of individual negotiations of public payers with pharmaceutical companies which are confidential. However, framework agreements, to which all or the majority of pharmaceutical companies of a country adhere, are rarely concluded. Laws and regulations stipulate and officially announce the amount of price reductions or refunds in some countries. In a few countries a “regulation-free zone” is in place concerning discounts in the framework of the existing pharmaceutical policies (Bulgaria, Latvia). Tendering, which comprises “any formal and competitive procurement procedure through which tenders/offers are requested, received and evaluated for the procurement of goods, works or services”, is typically applied in the in-patient sector; only a few countries use tendering in the out-patient sector (Table 2).

In some countries the individual negotiations with pharmaceutical companies are led by one single public body (e.g. Main Association of the Austrian Social Security Institutions, National Health Insurance Fund in Bulgaria, Italian Medicines Agency) whereas in other countries several public players negotiate individually with companies (e.g. several sickness funds in the Czech Republic and in Germany).

Depending on the organisation of the health care sector tendering and/or individual negotiations on discounts and/or rebates in the in-patient sector are performed either by a single body (e.g. the Hospital Purchasing Agency AMGROS in Denmark, the “Central Administration of the Health System” ACSS – entity responsible for managing NHS providers funding, including hospitals, in Portugal) or by individual hospitals or procurement groups of hospitals (e.g. Austria, Germany, Finland, France, Hungary).

The frequency, duration and renewal of such agreements differ. Whereas some countries (e.g. France) conclude agreements on a yearly basis, there are others with longer validity periods such as two or three years (e.g. Austria, Croatia, Italy). Agreements can also be concluded temporarily in response to the introduction of a specific product and/or therapeutic alternative (e.g. Portugal) or to the development in pharmaceutical expenditure (e.g. Turkey).

Table 2. Type of contracts and agreements on discounts and rebates of public payers with pharmaceutical companies in the out-patient sector in 31 European countries, 2011

| Types | Countries |

| Laws/regulations | Belgium, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Turkey |

| Framework agreements | Austria, Ireland, United Kingdom |

| Individual negotiations | Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia |

| Tendering | Denmark1, Germany, Netherlands |

1 The tendering procedure in place in Denmark in the out-patient sector is not considered as a discount policy by country representatives.

Range of discounts and rebates in the out-patient sector

The range of discounts and rebates to be achieved differs with regard to the type and country.

Discounts and rebates can be designed to be shared by all actors (pharmaceutical companies, wholesalers, pharmacies) in the pharmaceutical supply chain (e.g. in Spain). In two countries (Italy, United Kingdom), companies have the choice between price reductions (and price modulation in the UK) or payments back to public payers (Table 1).

Table 3. Range of discount and rebates in 31 European countries, 2011

| Types | Range | Countries |

| Price reductions on specific medicines resulting from individual negotiations | 0 – 50% of the respective price | Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia |

| Price reductions on medicines mentioned in laws/regulations | 3% – 32.5% | Belgium, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Turkey |

| Refunds/pay back mechanisms linked to sales volume of pharmaceutical companies | 1% – 8% of the sales | Austria (~1%), Belgium (6.73%), Croatia (confidential), France, Germany, Ireland (4%), Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain (1.5-2%), United Kingdom |

Coverage: All 27 European Union Member States except Poland and Romania plus Albania, Croatia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey.

Discussion

The survey provided evidence that pharmaceutical companies grant different kinds of discounts and rebates on reimbursable medicines to public payers. Information on discounts and rebates was reported from 25 of the 31 European countries from which information was provided. Discounts and rebates most frequently indicated are price reductions (in the out-patient and in-patient sectors), followed by refunds linked to sales volume (a measure particularly applied in the out-patient sector). Further discounts and rebates reported by some countries include in-kind support, price-volume and risk-sharing agreements. Differences exist among the countries regarding the types and extent of these measures as well as their design and place in the organizational and legal framework. Individual negotiations are the most common contractual arrangement.

The study sheds lights onto a very sensitive area in which scant literature exists and difficulties in assessing information due to confidentiality clauses were expected. The high response rate is therefore strength of the study.

The methodological approach chosen was a PPRI query, i.e. a survey with members of the PPRI network. There are only two parties in a country who know about such discounts and rebates: public payers and the pharmaceutical industry. We chose to address the public payers firstly because they had expressed interest in this issue under the framework of the PPRI initiative and motivated us to undertake the survey, and secondly because we could build on a good cooperation and a common understanding with them. The PPRI secretariat, which some of the authors are affiliated to, has been working for years on developing a joint language via the production and constant review of a glossary of pharmaceutical terms [28] and terminology trainings, and for this study we carefully defined the terms.

The high response rate to the questionnaire (14 responses within two weeks, and a total of 31 countries in the final compilation) confirmed the appropriateness of our approach. It clearly exceeded the average rate of nine answers to a PPRI query, thus endorsing the interest of public payers.

Despite thorough consideration of the terminology issues, misunderstandings occurred: We had to exclude a few answers (e.g. those referring to discounts and rebates granted in the distribution chain only which were not in the scope of this study). Open-ended questions included in the questionnaire helped to get a more complete picture but some responses were inconsistent, because, for instance, some countries listed their managed-entry arrangements such as risk-sharing agreements, while others did not. Knowing about further risk-sharing and managed entry agreements in some countries [18-20], we acknowledge that not all such agreements were reported in our study because managed-entry agreements were not the primary focus of our study. We cannot rule out the possibility that the mapping exercise might miss one or the other discount and rebate being in place in a country. So, potential under-reporting is a limitation of our study.

Discounts and rebates might be used instead of statutory price regulation. Most European countries, however, have price control for medicines funded by public payers (on average around two third of pharmaceutical expenditure are covered by public payers [7,8, 27]. The two free-pricing countries in the European Union are currently Denmark and Germany [6-8, 27], even though Germany is currently moving to some form of price control. Germany has been applying a rebate procedure: In addition to a published fixed rebate granted by the pharmaceutical industry, further rebates are negotiated between the company and the sickness funds. Each sickness fund is allowed to conclude contracts with manufacturers, complementing or modifying the collective price negotiation scheme [12].

The other free-pricing country, Denmark, uses like Germany tendering in the out-patient sector [10, 14]. Even if Danish officials do not consider this measure as a discount policy but as a mechanism to foster competition (tenders are made at frequent intervals of every two weeks [15, 34, 35], this policy is worth being mentioned in the context of this study because the tendering process leads to discounted prices. Tendering in the out-patient sector is also applied in the Netherlands which is currently liberalizing its pricing system (personal communication).

Discounts and rebates to public payers are also a reality in several European countries which control medicines prices. In those cases, the measures appear to be taken in order to accompany existing regulation (e.g. price control) and policy measures (initiatives to promote generics, a more rational use of medicines, etc.) since payers are under pressure to achieve savings. The need for cost-containment has been aggravated by the global financial crisis which required from the authorities to implement a bundle of, sometimes rather strict, policies [8]. Arrangements on discounts and rebates have resulted in the commitment of the pharmaceutical industry to contribute to savings in situations when companies would have opposed other, more “classical” or severe cost-containment measures. Discounts and rebates may also be considered as a policy option for payers in smaller markets which might not be attractive enough for pharmaceutical industry otherwise [36, 37]. In particular with regard to prices for generics medicines, some smaller European countries have shown that they are able to achieve discounts from pharmaceutical industry [38]. Furthermore, such discounts and rebates offer an opportunity for pharmaceutical companies to compensate for the lower purchasing power of some countries without offering incentives for arbitrage. Generally speaking, discounts and rebates are offered by the industry as part of their marketing strategy to gain market shares.

It appears at first glance that discounts and rebates offer a win-win situation for the two parties involved. It could therefore be suggested that they also benefit patients by securing the financial basis of the payers which would then be able to fund further medicines purchase. But it is an obstacle to transparency, as examples from other parts of the world have also shown [39, 40]: most of the discounts and rebates agreements are, as the survey results confirmed, confidential, and even if stipulated by law, the individual extent negotiated is still confidential between the payers and the companies. This again impacts other policies, in particular external price referencing (international price comparisons) which is in place in several European countries [27, 41]. There is concern that the discounts and rebates impede price transparency, since price comparisons are usually made with reference to official list prices whereas the actual prices are lower [41]. In Spain one of the emergency measures in response to the global financial crisis was a discount on original products instead of a price cut because this was accepted by industry which shares the discount with the other actors in the distribution chain [8]: Though this discount is generally known, international price comparisons will be continue to consider the non-discounted prices [42].

The example of Spain suggests the external price referencing policy being another reason for the existence of discounts and rebates in European countries. When this pricing policy is applied, companies which have a strategic interest to have high list prices to be compared to [41] react by offering discounts and rebates.

The results also confirmed that discounts and rebates are a common feature in the in-patient sector, as evidenced in other studies [33, 43]. Concern for limited transparency is raised again because actual hospital prices are usually not known in the European countries [33]. Furthermore, unbalanced market power might be another issue in the hospital sector: While payers in the out-patient sector usually cover the whole country (in case of a National Health Service or a single payer Social Health Insurance institution) or parts of the population (e.g. sickness funds, regions), the relevant contacts for pharmaceutical companies in the in-patient sector are often individual hospitals or hospital associations. There are indications that larger hospitals receive larger discounts [44], but further components (e.g. on-patent “monopoly products” without therapeutic alternative) also play a role [33].

While we do not claim that our study provides conclusive evidence about all types of discounts, rebates and refunds granted by the pharmaceutical industry to public payers, it confirms in a systematic way that such measures do play a substantial role in European countries. For public payers it is valuable information to have an overview of the situation in other European countries and to learn about possible pitfalls of such discount and rebate agreements. Public payers must be aware that the advantages of such agreements, i.e. savings which might otherwise not have been possible and as such result in a contribution to increased accessibility of medicines, are flawed by reduced transparency, in particular by a distortion of medicines prices. With increasing use of discounts and rebates, which are often “hidden price cuts”, policy makers and researchers have to be mindful of creating a situation in which the surveyed list prices may provide at best only an indication of but do not reflect actual prices. This might be remedied by a price survey in the pharmacies and dispensing points in line with the WHO/HAI price survey methodology [45-47].

Conclusions

Discounts and rebates which pharmaceutical companies grant on reimbursable medicines to public payers appear to be a frequently applied policy in European countries. They tend to be used as a complimentary measure when price regulation does not achieve the desired results and in the few European countries with no or limited price regulation. Discounts and rebates usually serve cost-containment purposes and/or the management of uncertainty and allow pharmaceutical companies to gain market shares. Whereas these measures are likely to offer a win-win situation to the two parties involved (public payer and pharmaceutical industry), they tend to be detrimental to transparency because these agreements, or at least their details, are confidential and may lead to a distortion of medicines prices. Since this study aimed to provide a mapping for Europe and did not go into an in-depth analysis of some specific regulations and agreements, further research is recommended.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the paper’s conception, design and production. SV wrote major parts of the article and revised the article following contributions from NZ, CH, JP and AB and feed-back by PPRI network members. NZ developed the questionnaire in close cooperation with the co-authors, performed the survey, compiled the results and drafted the results section. NZ acted as key contact to the respondents of the questionnaire. All authors critically revised the article and have approved the final version for submission.

Conflict of interest

None

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the members of the PPRI network (competent authorities for pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement in the 27 EU Member States and thirteen further countries; see http://whocc.goeg.at/Networks/ListOfMembers) who participated in this mapping exercise: They responded to the questionnaire, were available for clarification and reviewed the draft article. According to the information policy agreed within the PPRI network, the names of the PPRI participants are not published. Furthermore, we thank Dr. Richard Laing, WHO Headquarters, for critically reviewing the article.

Funding Statement

Research of the WHO Collaborating Centre (WHO CC) for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies was done under the framework of the PPRI (Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information) project. Funding for PPRI and WHO CC activities is provided by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Health which is legal owner of the Austrian Health Institute. This specific PPRI query was supported by a grant of the Austrian Main Association of Social Insurance Institutions (MASSI).

Footnotes

i It is PPRI’s policy not to list the names of staff and officials of institutions represented. The PPRI member institutions are listed on the website of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies under the section “networks”: http://whocc.goeg.at/Networks/ListOfMembers.

References

- 1.Hogerzeil Hans V. The concept of essential medicines: lessons for rich countries. BMJ. 2004;329(7475):1169–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1169. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/15539676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogerzeil Hans V. Essential medicines and human rights: what can they learn from each other. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(5):371–5. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.031153. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/16710546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laing R, Waning B, Gray A, Ford N, t Hoen E. 25 years of the WHO essential medicines lists: progress and challenges. The Lancet. 2003;361(9370):1723–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13375-2. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/medicines.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quick Jonathan D, Hogerzeil Hans V, Velasquez Germán, Rago Lembit. Twenty-five years of essential medicines. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(11):913–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/12481216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pharmaceutical pricing policies in a global market. Paris: OECD; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogler S. Preisbildung und Erstattung von Arzneimitteln in der EU - Gemeinsamkeiten, Unterschiede und Trends. Pharmazeutische Medizin. 2012;14(1):48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogler Sabine, Habl Claudia, Bogut Martina, Voncina Luka. Comparing pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies in Croatia to the European Union Member States. Croat Med J. 2011;52(2):183–97. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.183. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/21495202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Leopold C, de Joncheere K. Pharmaceutical policies in European countries in response to the global financial crisis. Southern Med Review. 2011;4(2):32. doi: 10.5655/smr.v4i2.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dylst Pieter, Vulto Arnold, Simoens Steven. Tendering for outpatient prescription pharmaceuticals: what can be learned from current practices in Europe. Health Policy. 2011 Apr 21;101(2):146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.03.004. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=21511353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuidberg C. The pharmaceutical system of the Netherlands. A comparative analysis between the Dutch out-patient pharmaceutical system, in particular the pricing and reimbursement characteristics, and those of the other European Union Member States, with a special focus on tendering-like systems. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dauben H-P, Stargardt T, PPRI Busse R. PPRI Pharma Profile Germany. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH / Geschäftsbereich ÖBIG; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ognyanova D, Zentner A, Busse R. Pharmaceutical reform 2010 in Germany. Eurohealth. 2011;17(1):11–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leopold C, Vogler S, Habl C. Was macht ein erfolgreiches Referenzpreissystem aus? Erfahrungen aus internationaler Sicht [in German] / Implementing a successful reference price system – Experiences from other countries. Soziale Sicherheit. 2008;11:614–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanavos P, Seeley L, Vandoros S. Tender systems for outpatient pharmaceuticals in the European Union: Evidence from the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium. LSE Health. 2009.

- 15.Habl C, Vogler S, Leopold C, Schmickl B, Fröschl B. Referenzpreissysteme in Europa. Analyse und Umsetzungsvoraussetzungen für Österreich. Wien: ÖBIG Forschungs- und Planungsgesellschaft mbH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arickx F. The “price regulation” experience – Belgium. Presentation at the informal session "Pricing And Reimbursement Of Generic Medicines: Policy Outlook And Market Impact" organised by the European Commission. DG ENTR., 2009/07/15.

- 17.DeSwaef A, Antonissen Y. PPRI Pharma Profile Belgium. Vienna: Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamski Jakub, Godman Brian, Ofierska-Sujkowska Gabriella, Osińska Bogusława, Herholz Harald, Wendykowska Kamila, Laius Ott, Jan Saira, Sermet Catherine, Zara Corrine, Kalaba Marija, Gustafsson Roland, Garuolienè Kristina, Haycox Alan, Garattini Silvio, Gustafsson Lars L. Risk sharing arrangements for pharmaceuticals: potential considerations and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:153. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-153. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espín J, Rovira J, García L. Experiences and Impact of European Risk-Sharing Schemes Focusing on Oncology Medicines. EMINet. 2011.

- 20.Kanavos P, Ferrario A, Espin J. Managed Entry Agreements for Pharmaceuticals: The European Experience (unpublished) EMINet. 2011.

- 21.Kanavos Panos, Taylor David. Pharmacy discounts on generic medicines in France: is there room for further efficiency savings. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2467–76. doi: 10.1185/030079907X219571. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=17764613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simoens S, De Coster S. Sustaining Generic Medicines Markets in Europe. Journal of Generic Medicines. 2006;3(4):257–68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simoens S. Developing Competitive and Sustainable Polish Generic Medicines Market. Croat Med J. 2009;50(5):440–8. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.440. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/19839067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanavos P, Schurer W, Vogler S. Pharmaceutical Distribution Chain in the European Union: Structure and Impact on Pharmaceutical Prices. London/Vienna: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simoens S. A review of generic medicine pricing in Europe. GaBI Journal. 2012;1(1):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucsics A. Current issues in drug reimbursement. Clinical Pharmacology. In: Müller M, editor. Current Topics and Case Studies. Vienna: Springer; 2010. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogler S, Habl C, Leopold C, Rosian-Schikuta I. PPRI Report. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH / Geschäftsbereich ÖBIG; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies. Glossary of pharmaceutical terms. Vienna: WHO; 2011. http://whocc.goeg.at/Glossary/Search. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arts D, Habl C, Rosian I, Vogler S. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI): a European Union project. Italian Journal of Public Health. 2006;3(1):41. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogler S, Espin J. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI) - New PPRI analysis including Spain. Pharmaceuticals Policy and Law. 2009;11:213–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31.PPRI / PHIS Pharma Profiles, 2007-2011. PPRI network members; http://whocc.goeg.at/Publications/CountryReports. [Google Scholar]

- 32.PHIS Hospital Pharma Reports, 2009-2011. PHIS network members; http://whocc.goeg.at/Publications/CountryReports. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogler S, Habl C, Leopold C, Mazag J, Morak S, Zimmermann N. Pharmaceutical Health Information System. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH / Geschäftsbereich ÖBIG; 2010. PHIS Hospital Pharma Report. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leopold C, Habl C, Rosian-Schikuta I. Steuerung des Arzneimittelverbrauchs am Beispiel Dänemarks. Buch, Monographie. Wien: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH / Geschäftsbereich ÖBIG; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomsen E, Er S, Fonnesbæk Rasmussen P. PPRI Pharma Profile Denmark. Vienna: PPRI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Report of Task Force of HMA MG. Madeira: Heads of Medicines Agencies; 2007. Availability of Human Medicinal Products. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leopold C, Rovira J, Habl C. Generics in small markets or for low volume medicines European Union. Vienna: EMINet; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garuoliene Kristina, Godman Brian, Gulbinovič Jolanta, Wettermark Björn, Haycox Alan. European countries with small populations can obtain low prices for drugs: Lithuania as a case history. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(3):343–9. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson Jane, Walkom Emily J, Henry David A. Transparency in pricing arrangements for medicines listed on the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Aust Health Rev. 2009;33(2):192–9. doi: 10.1071/ah090192. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=19563308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray AL. Medicine Pricing Interventions – the South African experience. Southern Med Review. 2009;2(2):15–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leopold Christine, Vogler Sabine, Mantel-Teeuwisse A K, de Joncheere Kees, Leufkens H G M, Laing Richard. Differences in external price referencing in Europe: a descriptive overview. Health Policy. 2011;104(1):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Leopold C, Schmickl B, Windisch F. Drug Utilisation and Health Policy Meeting; Antwerp: EuroDURG. Antwerp: 2011. Impact of medicines price reductions in Greece and Spain on other European countries applying external price referencing (Poster) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Leopold C, Habl C, Mazag J. PHP22 Are Hospital Medicines Prices Influenced by Discounts and Rebates. Value in Health. 2011;14(7):A337. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikou K, Perdikouri K. Critical appraisal of a new medicines pricing policy in Greek hospitals. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy: Science and Practice. 2012;19(2):130. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2008 Nov 29;373(9659):240–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61762-6. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=19042012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medicine Prices. A new approach to measurement. Working draft for field testing and revision. WHO, Health Action International (HAI); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Measuring medicine prices, availability, affordability and price components. Geneva: WHO, Health Action International (HAI); 2008. [Google Scholar]