Abstract

Objective: Access to medicines has long been and remains a challenge in African countries. The impact of medicines registration policies in these countries poses a challenge for pharmaceutical companies wanting to register medicines in these countries. The recent AMRHI (African Medicines Registration Harmonisation Initiative) has increased the focus on the need for harmonisation. Medicines registration regulations differ across African countries. Anecdotal evidence, based on the experience of pharmaceutical companies on progress towards harmonisation is somewhat different, i.e. that country specific requirements were a barrier to the registration of medicines. The objective of this study was therefore to determine the nature and extent of regulatory hurdles experienced by pharmaceutical companies who wish to register and supply medicines to African countries.

Methods: This cross-sectional descriptive pilot study was conducted across pharmaceutical companies, both local and multinational. These companies were based in South Africa and were also members of Pharmaceutical Industry Association of South Africa (PIASA). The pharmaceutical companies supply both the private and public sectors. An online survey was developed using Survey Monkey. Survey questions focused on the following strands: nature and level of current supply of medicines to African countries by companies, general regulatory requirements, region specific questions and country specific questions across four regional economic communities in Africa, namely; Southern African Development Community (SADC), East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of the West African States (ECOWAS) and Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS).

Results: A total of 33 responses were received to the questionnaire of which 26 respondents were from the PIASA Regulatory working group and 7 were from the PIASA Export working group.It was noted that since most of the regulatory authorities in Africa are resource-constrained, harmonisation of medicine registration policies will contribute positively to ensuring the safety, quality and efficacy of medicines. The experience of pharmaceutical companies indicated that country specific regulatory requirements are a barrier to registering and supplying medicines to African countries. In particular, GMP inspections, GMP inspection fees and country specific labeling were cited as key problems.

Conclusion: Pharmaceutical companies operating in African markets are experiencing difficulties in complying with the technical requirements of individual African countries. Further research is required to provide a balanced perspective on the country specific regulatory requirements vs. the African Regulatory Harmonisation Initiative (AMRHI).

Keywords: medicine registration, labeling, pharmaceutical policy, Good Manufacturing Practice

Introduction

Medicines are essential to healthcare and should be available to the inhabitants of every country. Medicines regulation aims to ensure that medicines circulating in national and international markets are safe, effective and of good quality, are accompanied by complete and correct product information, and are manufactured, stored, distributed and used in accordance with good practices [1].

For many years, African medicines regulatory authorities (MRAs) have managed a broad range of responsibilities, often with limited resources [2]. Their focus has generally been on providing their population with access to a wide range of affordable essential medicines, usually multi-source generics, with less emphasis on rapid access to the latest products. As a result, African national MRAs may have experience in managing generics, but many have only limited experience in assessing, approving and registering innovator products, the vast majority of which are for global chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension and cancer [2].

It is well documented that the African MRAs are under resourced and lack skills and capacity to perform their functions adequately [1, 3, 4]. Coupled with this is changing technology as well as advancements made in medicines, e.g. the increased development of biological medicines and the increased focus on healthcare in Africa. It is clear that intervention is required to ensure that the gap between African MRAs and developed country MRAs and the healthcare needs of their populations do not widen.

The African Medicines Registration Harmonisation (AMRH) Initiative is a welcome move. Investing in the AMRH initiative also provides an opportunity for African countries to strengthen their regulatory capacity, use their financial and human resources more effectively, thereby creating a more conducive environment for the attainment of the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [5].

Very little data is available regarding pharmaceutical companies experiences in registering and supplying medicines in Africa. This study aims to shed light on the pharmaceutical companies’ experiences with regards to compliance with technical requirements of medicines registration. This in turn can have an impact on the availability of medicines in African markets.

Objectives

The objective of this survey was to determine both the nature and extent of regulatory hurdles as experienced by pharmaceutical companies in seeking registration or market authorisation for medicines in African countries.

Methods

Data collection

For this cross-sectional descriptive pilot study a short survey was developed. The target groups for the survey were the Pharmaceutical Industry Association (PIASA) Export and PIASA Regulatory working groups. The Pharmaceutical Industry Association is the largest trade association in South Africa representing multinational and local companies. The group consists of individuals that have responsibility for either commercial or regulatory issues related to medicine registration in the African countries that the companies supply medicines to. Members of the Regulatory and Export working group of PIASA member companies were invited to complete the survey via email containing a hyperlink to the online survey during April 2010. Reminders were sent during April to July 2010 and the survey was closed at the end of July 2010. Separate surveys were sent to the Export and Regulatory groups of PIASA.

Only one response per company, per function, i.e. export and regulatory, was accepted to avoid duplication of responses. In instances where more than person responded from a particular company, duplicate responses were allowed only where it was appropriate to provide a more comprehensive view to a particular question. An online survey was developed using Survey Monkey. Through the experience of previous PIASA submissions to regulatory authorities and through anecdotal feedback from PIASA Export and Regulatory working groups, questions were developed to address key issues. Survey questions focused on the nature and level of current supply of medicines to African countries, availability of generics and decision-making around medicine supply and views and experiences in dealing with regulatory requirements. The questions regarding GMP requirements and country-specific requirements were posed across four regional economic communities in Africa which include: Southern African Development Community (SADC), East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of the West African States (ECOWAS) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). The survey also included open-ended questions to allow respondents to express their views freely and in an unstructured manner.

Data Analysis

Proportions were used in descriptive analyses of dichotomous and categorical variables. Country and regional categorisation was based on the country listing per Regional Economic Communities (RECs), as per the African Medicines Registration Harmonisation Initiative (AMRHI). The four RECs were East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Some countries belong to more than one REC – refer to Table 1 for country listing for each REC, highlighting overlapping countries [5].

Table 1. Country listing of four Regional Economic Communities in Africa

| SADC | ECCAS | ECOWAS | EAC |

| Angola | Angola | Benin | Burundi |

| Botswana | Burundi | Burkina Faso | Kenya |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Cameroon | Cape Verde | Rwanda |

| Lesotho | Central African Republic | Cote d’Ivoire | Tanzania |

| Madagascar | Chad | Gambia | Uganda |

| Malawi | Congo | Ghana | |

| Mauritius | Democratic Republic of Congo | Guinea | |

| Mozambique | Equatorial Guinea | Guinea Bissau | |

| Namibia | Gabon | Liberia | |

| Seychelles | Rwanda | Mali | |

| South Africa | Sao Tome & Principe | Niger | |

| Swaziland | Nigeria | ||

| Tanzania | Senegal | ||

| Zambia | Sierra Leone | ||

| Zimbabwe | Togo |

Results

A total of 33 responses were received to the questionnaire of which 26 respondents were from the PIASA Regulatory working group and 7 were from the PIASA Export working group. After exclusion of duplicate responses it was found that the 14 companies were from the regulatory group and five companies were from the export group (four of these companies were also represented in the regulatory group). Not all respondents answered all the questions and therefore the number of responses per question varies.

Current vs. future supply of medicines in Africa

Results show a high level of participation of companies in the various countries in Africa. All companies supplied medicines to the SADC region; however, the combinations and country representations differ across companies. Medicine supply by these companies covered a broad spectrum of therapeutic areas including diseases where the prevalence in Africa is high (viz. anti-infectives, HIV/AIDS) and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) viz. oncology, endocrinology and cardiovascular disease. The top therapeutic areas for all medicines supplied were as as follows: cardiovascular, endocrinology, oncology, allergy and anesthesia. The top therapeutic areas for genericmedicines were cardiovascular, allergy, anti-infectives and endocrinology. Although the current supply of medicines by companies is significant, six companies indicated that they have made a decision not to supply medicines into some African markets. Specific countries mentioned included Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Reasons for companies (cited by the export group) in making decisions not to supply medicines to specific African countries were: registration costs; commercial; retention costs, GMP inspection fees and GMP inspection requirements. When asked in which markets these decisions have been made, the responses included Ghana, Uganda and Sudan. Overall, reasons related to the medicine registration process outweighed commercial or market reasons for these decisions.

All companies (five export group respondents) indicated that they had experienced instances where they were unable to supply medicines to African markets. The reasons cited for the interrupted supply were related to regulatory requirements, particularly medicines registration. One respondent cited concerns of product diversion to Western countries as the reason. The same five companies indicated that they had made decisions not to supply specific medicines to African countries. Only one company indicated that their products had been held back at customs – no additional information was provided. All five companies in the export group stated that their businesses were negatively impacted by the availability of unregistered medicines in African countries. The commercial impact of this was rated between medium and severe (medium =4; severe=1). One company mentioned Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique and Malawi as the countries where the availability of unregistered medicines was a problem.

Table 2. Reasons for non-supply of medicines (n=5)

| Reason | No. of Companies citing reason for not supplying medicines to specific African countries |

| Registration costs | 4 |

| Commercial | 3 |

| Retention costs | 3 |

| GMP Inspection fees | 3 |

| Lengthy registration | 2 |

| GMP inspection requirements | 2 |

| Unregistered medicine already available | 1 |

| Risk of counterfeit medicine | 1 |

| Generic medicine already available | 1 |

Registration of medicines

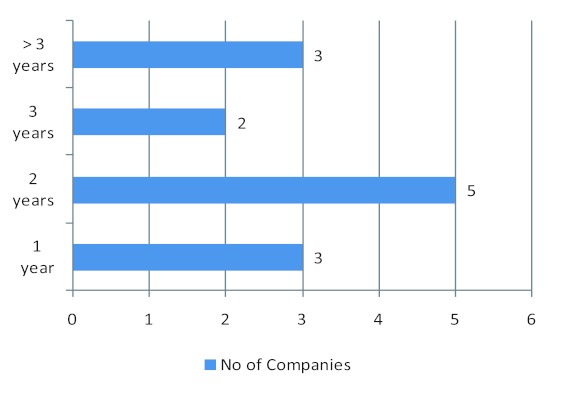

Registration timelines experienced by companies varied in general between one and three years although time could vary between countries and three companies indicated more than three years (Fig 1). Although the results were mixed in terms of whether current African medicines registration requirements are in line with international standards, some respondents indicated that there is a level of alignment with international standards. Nine companies indicated that the registration requirements in African countries were in line with international standards (Table 3).

The majority of respondents indicated that there was a lack of recognition of international standards by African regulatory authorities with no differences across RECs. Of the total of 14 companies, 13 stated that country specific requirements, in general, were problematic to implement. The three main areas that respondents found problematic were country-specific labeling requirements, GMP inspection requirements and GMP inspection fees. Another company indicated that the regulators lacked the expertise to register biologic agents.

GMP inspections have been cited by most companies operating in Africa as a barrier to the registration and supply of medicines. Seven companies noted that GMP inspection fees were too high, while seven companies indicated that GMP inspection requirements were a barrier to medicine registration (Table 3).Additional comments provided by the respondents included that the cost of maintaining the product was higher than the returns and sales volumes do not justify high costs nor cover registration renewal fees. A correlation was identified between commercial decisions not to supply medicines and GMP issues in specific countries (Table 4).

Figure 1. Reported timelines for medicine registration (n=14, 1 company did not provide a timeline).

Table 3. Summary of survey results across the different Regional Economic Communities

| Question | EAC N=11 |

ECCAS N=8 |

ECOWAS N=8 |

SADC N=14 |

| No. of Products supplied to African countries (no. of responding companies) | 10 | 7 | 10 | 14 |

| ≤10 products 11-20 products >20 products |

3 3 4 |

4 3 2 |

3 1 3 |

6 4 5 |

| Alignment of registration requirements with international standards (no. of respondents)* | 11 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| True True in some cases False in some cases False No information known |

1 6 1 2 1 |

1 5 1 0 1 |

1 4 1 1 1 |

2 9 1 2 1 |

| Lack of recognition of international standards (no. of respondents) | 10 | 7 | 7 | 15 |

| Yes No |

9 1 |

6 1 |

6 1 |

13 2 |

| Are GMP inspection requirements a barrier to registration of medicines? (no. of respondents)* | 9 | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Yes No No opinion |

7 0 2 |

6 0 1 |

5 0 2 |

8 1 5 |

| Views on GMP inspection fees (no. of respondents)* | 10 | 7 | 7 | 15 |

| Too high Appropriate Too low Unknown |

7 1 0 2 |

5 1 0 1 |

4 1 0 2 |

7 2 0 6 |

| Are country specific labeling requirements problematic to implement for supply of medicine to African markets? (no. of respondents)* | 10 | 6 | 7 | 14 |

| Yes No Not applicable |

10 0 0 |

6 0 0 |

7 0 0 |

13 1 0 |

Table 4: Countries where companies experience problems with GMP inspections

| Region | GMP issues | Commercial decision not to supply |

| SADC | Tanzania | Tanzania |

| South Africa | ||

| Botswana | ||

| Mozambique | Mozambique | |

| Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe | |

| ECOWAS | Ghana | Ghana |

| Nigeria | Nigeria | |

| Togo | ||

| EAC | Kenya | Kenya |

| Uganda | ||

| ECCAS | None | None |

Withdrawal/discontinuation of medicines (export and regulatory)

Of concern is that nine companies indicated that they have stopped supplying between one and five products. When probed for reasons for the withdrawal of the products from market, the reasons cited include registration, renewal and GMP inspection fees. One company indicated that their product had been replaced by a more innovative/convenient dosage form while another stated that opportunistic distributors and parallel importers bringing in counterfeit and cheap generics had led them to withdraw their products. The therapeutic areas, in which the products were withdrawn, included allergy, anti-infective, gastroenterology, HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular, metabolic disorders, pain management, psychiatry and gynecology. Eleven companies indicated that counterfeit medicines were a problem in some markets in Africa; specifically Kenya and Uganda. Respondents were also asked to supply reasons for the interrupted supply to determine a link, if any, to regulatory requirements. Reasons cited included delays in approval of post registration amendments to registration dossiers.

African Medicines Registration Harmonisation Initiative (AMRH)

Overall, 82% of respondents were positive about the AMRHI. While providing additional feedback some respondents stated that previous attempts at achieving harmonization had failed due to a lack of political will and commitment to implement.

Survey respondents were asked about their views on the public health impact of the current requirements for registration of medicines in African markets. There were strong views expressed regarding the delayed access to medicines and the resultant impact on health outcomes for patients. Another view was that having stringent regulatory requirements would contribute to keeping counterfeit medicines out of the market. Ethiopia was cited as an example of good management in this regard by requiring that medicines need to be on the essential drug list (EDL) before they can be registered.

Discussion

The pharmaceutical companies that participated in the survey have a strong presence in African markets. Overall, the majority of companies indicated that technical issues related to the registration and supply of medicines to these countries were problematic to implement and also a barrier to supply. Although there is some literature on the resource constraints of regulatory authorities in Africa [1, 3, 4, 5], we were unable to find data on pharmaceutical company experience in registering and supplying medicines to Africa. The question explored in this study was whether technical requirements for medicine registration was considered a barrier to registration and supply of medicines. The results showed that country specific requirements, in particular, are problematic to implement. The survey results indicated a link between pharmaceutical companies experiencing interrupted supply and regulatory requirements. The lack of alignment with international standards, impact of counterfeit medicines, GMP inspections, have impacted and will continue to impact product supply, unless changes are made to country-specific requirements as well as the recognition of international standards.

International standards contribute greatly to companies’ ability to comply with regulatory requirements and from the regulator’s point of view [6], it ensures not only that high standards are maintained but it also assists with functioning optimally in a resource constrained environment [7, 8, 9]. An efficient, predictable registration timeline will promote access to new medicines by encouraging more companies to register medicines in Africa. It is expected that this will positively impact the availability of medicines.

Country specific labeling requirements increase the cost of medicines to specific African countries and in some cases pharmaceutical companies either cease to supply medicines or have made decisions not to supply new medicines to these countries.

The costs, for GMP inspections, were cited as prohibitive by respondents when considering registration and supply of medicines to specific African markets. The potential impact of increased number and frequency of GMP inspections include potential delays in approval and medicine supply. Furthermore, the cost of GMP inspections could be a deciding factor in whether companies pursue registration in a country or not.

Opportunity costs in this context can be defined as the number of products that will not be registered or supplied to specific African markets therefore resulting in revenue losses for the NMRA as well as the pharmaceutical companies concerned. Perhaps more importantly, there are costs to the healthcare system as a result of the unavailability of certain medicines [10, 11].

Current regulatory requirements should be carefully scrutinized to determine whether they are value-added or non-value added with respect to the medicine registration process. In this way, the current registration processes can be streamlined, thereby shortening the overall registration timeline for medicines. There is a pressing need to address some of the regulatory burdens experienced by pharmaceutical companies in the short term, which will not only alleviate the current issues cited, but will also contribute positively to the achievement of the objectives of the AMRHI.

Medicine registration harmonisation will positively impact all stakeholder groups as illustrated in Figure 2 [5, 8, 10]. Regulatory authorities will benefit in terms of improved expertise, collaboration with other regulatory authorities and operational efficiency through sharing of information and recognition of established regulatory authority decisions. Healthcare professionals will benefit through the availability of more treatment options in order to optimise patient management. Pharmaceutical companies will benefit through the establishment of new markets and the improved ability to comply with regulatory requirements related to medicine registration. Patients will benefit through improved supply of medicines, access to high quality medicines that comply with stringent requirements of safety, quality and efficacy and reduced risk of use of counterfeit medicines.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and that there may be bias in responses which is inherent in self reported data. The small sample size did include diverse companies, including multinational, R&D based and local generic companies. It is acknowledged that opinions may differ even between representatives from the same company. The literature states that NMRAs in Africa have to face a multitude of issues affecting medicine regulation under sometimes severely resource constrained circumstances [3, 4, 5]. Risks of over-regulation and under-enforcement are very real and can be avoided through co-operation amongst regulatory agencies that are better resourced and skilled in maintaining the highest levels of technical standards. Further research is required to understand the regulator perspectives on country specific requirements which at face value seem to be at odds with the objectives of the African Medicines Regulatory Harmonisation Project.

Figure 2. Benefits of Harmonisation [adapted from reference 5, 8 & 10].

Conclusion

It is clear from the results of this survey that pharmaceutical companies operating in Africa are experiencing difficulties in complying with the technical requirements of individual African markets. The level of complexity is increased by the consolidated manufacturing and internal supply chain arrangements within pharmaceutical companies. Managing internal and regulatory compliance requirements is resulting in companies making decisions not to supply medicines to specific African markets. There also seems to be a disconnect between the objectives of the AMRHI and the experiences of pharmaceutical companies at a country level. It is recommended that further research is undertaken in-order to investigate country specific requirements both in terms of intention and impact and also from pharmaceutical company and regulator perspectives.

Authors’ Contributions

Kirti Narsai had the original idea for the paper and wrote the first draft, which was based on information requirements expressed by Eric Buch. Kirti Narsai designed the questionnaire in collaboration with Abeda Williams. Kirti Narsai also carried out the data analysis . Aukje Mantel-Teeuwisse contributed to drafting the article and reviewing the data analysis. All authors contributed to the revision of the paper and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study. The Department of Pharmacoepidemiology and Clinical Pharmacology, Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, employing Aukje Mantel-Teeuwisse has received unrestricted research funding from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ), the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association (KNMP), the EU Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), the EU 7th Framework Program (FP7), the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board, the Dutch Ministry of Health and industry (including GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer). Kirti Narsai is permanently employed by PIASA. Abeda Williams is permanently employed by Janssen.

Acknowledgments

The Pharmaceutical Industry Association of SA (PIASA) is a trade association of companies involved in the manufacture and/or marketing of medicines in South Africa. The membership of 18 companies includes a broad representation of foreign multinational pharmaceutical companies and local and generic companies, both large and small. We would like to thank the member companies, in particular the members of the PIASA regulatory and export working groups who participated in the survey. We would also like to say thanks to Prof Eric Buch (NEPAD Health Advisor), who requested data from the industry on harmonisation issues, which led to the development of this study.

Funding Statement

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

References

- 1.WHO Drug Information. 1. Vol. 24. World Health Organization; 2010. Regulatory Harmonisation. Updating medicines regulatory systems in sub-Saharan African countries; pp. 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi). Registering new drugs: The African context. New tools for new times. 2010 http://www.policycures.org/downloads/DNDi_Registering_New_Drugs-The_African_Context_20100108.pdf.

- 3.Assessment of medicines regulatory systems in sub-Saharan African countries. An overview of findings from 26 assessment reports. WHO; 2010. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js17577en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran Mary, Strub-Wourgaft Nathalie, Guzman Javier, Boulet Pascale, Wu Lindsey, Pecoul Bernard. Registering new drugs for low-income countries: the African challenge. PLoS Med. 2011 Feb;8(2):e1000411–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000411. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/21408102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sigonda M N, Ambali A. The African Medicines Regulatory Harmonisation Initiative: Rationale and Benefits. Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;89:176–178. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. Geneva: ICH; 2000. The value and benefits of ICH to industry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appropriate control strategies eliminate the need for redundant testing of pharmaceutical products. Geneva: IFPMA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molzon J A, Giaquinto A, Lindstrom L, Tominaga T, Ward M, Doerr P, Hunt L, Rago L. The value and benefits of the International Conference on Harmonisation to drug regulatory authorities: advancing harmonization for better public health. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Feb 16;89(4):503–12. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.African Medicines Regulatory Harmonisation. NEPAD and AU; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pécoul B. New drugs for neglected diseases: from pipelines to patients. PLoS Medicine. 2004;1(1):19–022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Roey J, Haxaire M. and Haxaire, M. The need to reform current drug registration processes to improve access to essential medicines in developing countries. Pharm Med. 2008;22(4):207–213. doi: 10.2165/1317117-200822040-00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

![Figure 2. Benefits of Harmonisation [adapted from reference 5, 8 & 10]](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/a586/3471191/3f3e451101f0/smr-05-031-g002.jpg)