Abstract

Background: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) aims to alleviate hunger among its beneficiaries by providing benefits to purchase nutritious foods.

Objective: We conducted a comprehensive dietary analysis of low-income adults and examined differences in dietary intake between SNAP participants and nonparticipants.

Design: The study population comprised 3835 nonelderly adults with a household income ≤130% of the federal poverty level from the 1999–2008 NHANES. The National Cancer Institute method was used to estimate the distributions of usual intake for dietary outcomes. Relative differences in dietary intake by SNAP participation were estimated with adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and household food security.

Results: Few low-income adults consumed recommended amounts of whole grains, fruit, vegetables, fish, and nuts/seeds/legumes. Conversely, many low-income adults exceeded recommended limits for processed meats, sweets, and bakery desserts and sugar-sweetened beverages. Approximately 13–22% of low-income adults did not meet any food and nutrient guidelines; virtually no adults met all of the guidelines. Compared with nonparticipants, SNAP participants consumed 39% fewer whole grains (95% CI: −57%, −15%), 44% more 100% fruit juice (95% CI: 0%, 107%), 56% more potatoes (95% CI: 18%, 106%), 46% more red meat (95% CI: 4%, 106%), and, in women, 61% more sugar-sweetened beverages (95% CI: 3%, 152%). SNAP participants also had lower dietary quality scores than did nonparticipants, as measured by a modified Alternate Healthy Eating Index.

Conclusion: Although the diets of all low-income adults need major improvement, SNAP participants in particular had lower-quality diets than did income-eligible nonparticipants.

INTRODUCTION

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)4, formerly the Food Stamp Program (FSP), is the largest of the 15 federal nutrition-assistance programs (1). SNAP eligibility is determined by having a household income ≤130% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and <$2000 in countable assets (2). In 2011, as a result of rapidly increasing participation, program costs totaled $75 billion (3). With 44.7 million individuals participating in SNAP in 2011, it is estimated that 1 in 7 persons in the United States are currently enrolled in the program (3).

SNAP aims to alleviate hunger among its beneficiaries by providing benefits to purchase nutritious food items (4). In 2008, the program name was changed to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to reduce the stigma and increase the focus on nutrition (5). Despite the recent name change, the program has not been restructured to provide incentives for beneficiaries to purchase nutrient-rich foods, to restrict the purchase of nutrient-poor foods with SNAP benefits, or to strengthen the SNAP nutrition education program. Currently, SNAP benefits can be used to purchase most foods and beverages, including nutrient-rich whole grains, fruit, and vegetables and nutrient-poor salty snacks, sweets, baked goods, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Alcohol, tobacco, dietary supplements, and hot or prepared foods are excluded.

Previous studies have suggested an association between SNAP participation and obesity, particularly in adult women (6–13). By using recently available data, we also found that SNAP participation was associated with greater adiposity, a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, elevated fasting glucose, and the metabolic syndrome (14). If these associations are causal, they may be mediated in part by poor dietary quality. However, the association between SNAP participation and dietary intake has not been as extensively studied as has SNAP participation with obesity. In some of the earlier studies, FSP participation was associated with greater intakes of meat, added sugars, and added fats (15) and inversely associated with vegetable and fish intake among adults in the 1994–1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (16). In 2004, a USDA review of 17 studies found that most studies did not support a difference in total energy, macronutrient, or micronutrient intake between SNAP adult participants and nonparticipants (17). Most recently, another USDA report using data from the 1999–2004 NHANES suggested that FSP children and adult participants had a lower overall Healthy Eating Index–2005 (HEI-2005) score than did their income-eligible nonparticipant and higher-income counterparts, although scores for all 3 groups were far from the maximum score (18).

We aimed to conduct a comprehensive dietary analysis of a recent nationally representative sample of low-income adults and to examine whether SNAP participants and nonparticipants differed in their consumption of foods and nutrients important for long-term health and chronic disease prevention. These differences were also examined within subgroups of sex, race-ethnicity, and poverty level. Last, we examined whether SNAP participation was associated with 2 measures of dietary quality: the HEI-2005 and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI). Because of the nature of the data, this study could not aim to determine how SNAP participation influenced dietary intake; however, the inclusion of sociodemographic covariates in regression models and stratification by subgroups allowed for more appropriate comparisons between SNAP participants and nonparticipants to better understand the potential effects of SNAP participation on overall dietary quality.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study population

NHANES is an ongoing, multistage cross-sectional survey administered by the National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES is designed to be representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population and collects information on general health status, nutritional intake, health-related behaviors, and physiologic measurements from an in-home questionnaire and an in-person physical examination in Mobile Examination Centers. This analysis combined data from the 1999–2008 surveys to maximize a sufficient representation of SNAP participants. The analytic sample was restricted to 3835 adults aged 20–65 y with a household income ≤130% of the FPL and with complete dietary data.

SNAP participation

Current SNAP participation was defined as providing an affirmative response to the question, “Are you now authorized to receive Food Stamps?” (1999–2006 NHANES) or answering ≤31 d to the “number of days between the time the household last received Food Stamp benefit and the date of the interview” (2007–2008 NHANES). Individuals were classified as nonparticipants if they gave a negative response to receiving Food Stamps within the previous 12 mo (1999–2008 NHANES) or ever having received Food Stamp benefits (2007–2008 NHANES). Recent past SNAP participants, defined as individuals who had received Food Stamps within the past 12 mo but were no longer receiving Food Stamps, were excluded to provide a clearer comparison between current SNAP participants and income-eligible nonparticipants (n = 152).

Dietary intake

During the in-person physical examination, one 24-h dietary recall was administered by a trained interviewer with use of the USDA's Automated Multiple Pass Method (19). From 1999 to 2002, one dietary recall was collected per study participant. Beginning in 2003, a second dietary recall was administered to all study participants over the phone 3–10 d after the first recall, which was taken during the in-person physical exam. Between 2003 and 2008, 93% of study participants completed two 24-h dietary recalls.

Foods, food groups, and nutrients

NHANES dietary files are provided as individual food files and total nutrient files. Data from the USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies were used to identify foods and food groups from the NHANES individual food files (20). Foods directly corresponding to the food group of interest were given full weight; mixtures (eg, mixed dishes, soups) were given half weight to account for the other constituents in the mixed food (see Table S1 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). Foods and food groups of interest included total grains, whole grains (including brown rice, popcorn, and any grain food with a carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio ≤10:1), refined grains (including any grain food with a carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio >10:1), fruit (excluding juices), 100% fruit juice, vegetables (excluding white potatoes and juices), eggs, fish/shellfish, nuts/seeds/legumes (excluding nut/seed butters), red meat (excluding processed red meats), processed meats, high-fat dairy products (whole- and reduced-fat dairy), low-fat dairy products (low-fat or fat-free dairy), sweets and bakery desserts (cakes, cookies, pies, pastries, syrups, gelatins, ices, candies), salty snacks (crackers, popcorn, pretzels, corn chips, potato chips, pork rinds), regular sodas, diet sodas, sports drinks and noncarbonated sugar-sweetened beverages, all sugar-sweetened beverages, and water. Servings were estimated by calculating the grams of intake of each food and applying common serving sizes.

Nutrient intakes were derived from the NHANES nutrient files. Nutrients of interest were total calories, EPA, DHA, α-linolenic acid, PUFA (% of energy), MUFA (% of energy), SFA (% of energy), dietary cholesterol, total fat (% of energy), total carbohydrate (% of energy), total protein (% of energy), folate, dietary fiber, sodium, potassium, calcium, and iron. For these analyses of dietary quality, nutrient contributions from dietary supplements were excluded. Consumption levels were compared with the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the 2006 American Heart Association dietary guidelines for foods and food groups, and the Institute of Medicine's age- and sex-appropriate Estimated Average Requirements or the Adequate Intakes for nutrients (see Table S2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue).

Dietary quality

Overall dietary quality was assessed by using the HEI-2005 and the AHEI. The HEI-2005 was developed by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion as a tool to measure compliance with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and it best captures the range of years over which the NHANES data were collected (21). The 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans was also the basis for the 2006 Thrifty Food Plan, which is the basis for SNAP benefit allotments. The HEI-2005 consists of 12 components based on consumption patterns per 1000 kcal to measure dietary quality: total fruit, whole fruit, total vegetables, dark-green vegetables/orange vegetables/legumes, total grains, whole grains, milk, meats, beans, oils, SFA, sodium, and discretionary calories from solid fats, added sugar, and alcoholic beverages. The maximum score is 100 points. The AHEI was developed by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health as a dietary pattern inversely related to chronic disease risk (22). The original AHEI consisted of 9 components to measure dietary quality: vegetables, fruit, nuts and soy protein, ratio of white to red meat, cereal fiber, trans fats, ratio of PUFAs to SFAs, multivitamin use, and alcohol. This study used a modified AHEI by excluding the trans fat component because trans fat content was unavailable in the NHANES dietary files. The maximum score was rescaled from 77.5 points (excluding trans fat) to the original 87.5 points for comparability with other studies.

Study covariates

Covariates of interest included age, sex, race-ethnicity, place of birth, highest level of education, marital status, household size, health insurance, poverty income ratio (in 25% increments), household food security, and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Missing indicators were used to account for missing information for educational level (n = 4), marital status (n = 75), health insurance (n = 33), food security (n = 5), and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (n = 849). Household food security was assessed by using the USDA 18-item US Food Security Survey Module (23).

Statistical analysis

To make nationally representative estimates, we used the NHANES complex survey weights that account for different sampling probabilities and participation rates for NHANES. Dietary weights were recalculated to reflect the probability of being sampled in the 10-y period and were used for analyses of dietary outcomes. All models were restricted to the study population of 3835 low-income adults. Before conducting the dietary analyses, we examined the appropriateness of combining data from surveys conducted in 5 waves by testing the significance of 2-factor interaction terms between SNAP participation and survey wave in the models for several dietary components during this 10-y period.

Weighted means and proportions were estimated for sociodemographic characteristics; differences between SNAP participants and nonparticipants were compared by using chi-square tests. Means and distributions of selected foods, food groups, nutrients, and dietary pattern component scores were estimated by SNAP-participation status for all low-income adults and by sex, race-ethnicity, and poverty level. Distributions of intake for foods, food groups, and nutrients were estimated by using a statistical method for usual dietary intake developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which accounts for the within-person variation of dietary intake while preserving the complex NHANES survey weighting scheme (24). The NCI method involves 2 or more days of 24-h dietary recalls and the use of 2 SAS macros: MIXTRAN and DISTRIB (25). Because repeated 24-h dietary recalls were collected from study participants only after 2002, the use of the NCI method on this data set inherently assumes that the distributions of usual dietary intake are relatively consistent during the study period (26). MIXTRAN estimates the probability of consumption using logistic regression with a person-specific random effect and accounts for the day of intake (eg, day 1 or day 2) and whether the intake day was a weekday (Monday–Thursday) or a weekend (Friday–Sunday). DISTRIB estimates the consumption amount from the dietary recall data on a transformed scale. The results from both parts are linked by using correlated person-specific random effects. The NCI method can be used to estimate the distribution of dietary components that are consumed daily (amount-only method) or episodically (correlated method). Dietary components were classified as being consumed daily if >99% of the study population had a >0 value for that food or nutrient; otherwise, it was classified as being consumed episodically. The amount-only method was applied to all nutrients except EPA and DHA. The correlated method was applied to all foods, food groups, and EPA and DHA. SEs were estimated by using the balanced repeated replication method, which accounts for the correlation among individuals in the same sampling cluster and the complex NHANES survey weighting scheme (27).

To estimate the mean relative difference (RD) in dietary intake between SNAP participation groups, linear regression models were fit for log-transformed dietary intake. RDs can be interpreted as the percentage RD between SNAP participants and nonparticipants by using nonparticipants as the reference group. Dietary intake values of 0 were recoded to half of the minimum amount consumed to preserve all individuals in the analysis after log transformation. Models were first adjusted for age, sex, and total energy and second for further study covariates. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and significance was considered at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

At the time of the survey, 24.3% of low-income adults in the study population currently received SNAP benefits. Characteristics of SNAP participants and income-eligible nonparticipants are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were evident between the 2 groups: 47.2% of SNAP participants had <12 y of education compared with 28.6% of nonparticipants, 84.2% of SNAP participants lived below the poverty line compared with 71.0% of nonparticipants, and 43.6% of SNAP participants experienced low or very low food security in the past year compared with 18.1% of nonparticipants. SNAP participants also differed significantly from nonparticipants with respect to age, sex, race-ethnicity, place of birth, marital status, and health insurance coverage.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of adults at ≤130% of the FPL1

| SNAP nonparticipants (n = 2917) | SNAPparticipants (n = 918) | |

| Age (y) | 39.5 ± 0.52 | 37.2 ± 0.7 |

| Female sex [n (%)] | 1482 (51.0) | 623 (70.9) |

| Race [n (%)] | ||

| Non-Hispanic white [n (%)] | 1042 (58.6) | 319 (49.0) |

| African American [n (%)] | 568 (13.4) | 321 (26.7) |

| Hispanic/Latino [n (%)] | 1186 (22.3) | 246 (20.6) |

| Other or multiple ethnicities [n (%)] | 121 (5.6) | 32 (3.7) |

| Born in the United States [n (%)] | 1848 (76.5) | 744 (85.5) |

| Educational level [n (%)] | ||

| <12 y | 1194 (28.6) | 464 (47.2) |

| High school graduate | 707 (26.8) | 239 (27.7) |

| Some college | 726 (31.2) | 191 (21.9) |

| College graduate or higher | 287 (13.4) | 23 (3.2) |

| Marital status [n (%)] | ||

| Single | 655 (27.3) | 283 (34.9) |

| Married or living with partner | 1631 (54.2) | 329 (34.6) |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 563 (18.5) | 299 (30.5) |

| Household size (n) | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| Health insurance status [n (%)] | ||

| Not insured | 1281 (41.2) | 278 (28.2) |

| Insured with private insurance | 1102 (43.8) | 144 (13.7) |

| Insured with public insurance | 504 (15.0) | 493 (58.1) |

| Weight status [n (%)] | ||

| Underweight | 62 (2.7) | 26 (2.7) |

| Normal weight | 861 (33.2) | 218 (26.8) |

| Overweight | 952 (29.7) | 250 (25.8) |

| Obese | 981 (31.7) | 406 (42.5) |

| Poverty income ratio [n (%)] | ||

| 0–25% FPL | 953 (34.9) | 152 (18.8) |

| >25–50% FPL | 199 (7.3) | 162 (17.5) |

| >50–75% FPL | 366 (12.4) | 253 (26.7) |

| >75–100% FPL | 564 (16.4) | 209 (21.2) |

| >100–130% FPL | 835 (29.0) | 142 (15.7) |

| Household food security [n (%)] | ||

| Full | 2063 (76.1) | 370 (40.9) |

| Marginal | 256 (5.8) | 145 (15.5) |

| Low | 406 (12.5) | 250 (27.3) |

| Very low | 188 (5.6) | 152 (16.3) |

| Current household WIC participation | 28 (0.9) | 19 (3.6) |

All differences in sociodemographic characteristics between SNAP participants and nonparticipants (chi-square tests or univariate linear regression) were statistically significant (P < 0.05), except for household size. FPL, federal poverty level; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Mean ± SE (all such values).

Compared with national dietary guidelines, very few low-income adults consumed recommended amounts of whole grains, fruit, vegetables, fish, and nuts/seeds/legumes, regardless of SNAP-participation status (Table 2). Median whole grain consumption ranged from 0.2 to 0.5 servings/d. Median fruit and vegetable consumption was between 0.3 and 0.6 servings/d and 0.7 and 1.0 servings/d, respectively. For all low-income adults, median fish intake ranged from 1.2 to 1.7 servings/wk and median intake of nuts/seeds/legumes ranged from 1.7 to 2.7 servings/wk. Conversely, many low-income adults consumed amounts that met or exceeded recommended limits for processed meats (≤2 servings/wk), sweets and bakery desserts (≤2.5 servings/wk), and sugar-sweetened beverages (≤4 servings/wk). For processed meats, the median intake was between 1.9 and 2.0 servings/wk. Median intake of sweets and bakery desserts was between 0.6 and 0.9 servings/d. For all sugar-sweetened beverages, median weekly intake ranged from 13.4 to 16.1 servings; 10% of low-income adults consumed ≥39–43 servings/wk.

TABLE 2.

Consumption of selected foods, food groups, and nutrients among adults at ≤130% of the federal poverty level by SNAP participation1

| Age-and sex-adjusted |

Multivariate-adjusted2 |

||||||||

| Recommended intake | Mean | Median | Percentile (10th, 90th) | Met guideline | RD | 95% CI | RD | 95% CI | |

| Foods and food groups | |||||||||

| Total grains (servings/d) | 6–8 servings3 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 6.0 | 5.7 | (3.1, 9.6) | 26 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 5.1 | 4.9 | (2.3, 8.2) | 21 | 0.93 | 0.80, 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.82, 1.20 | |

| Whole grains (servings/d) | ≥3 oz equivalents4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.9 | 0.5 | (0.1, 2.2) | 5 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.5 | 0.2 | (0, 1.4) | 2 | 0.49* | 0.36, 0.66 | 0.61* | 0.43, 0.85 | |

| Refined grains (servings/d) | ≥3 oz equivalents4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 5.1 | 4.9 | (2.6, 7.9) | 85 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 4.6 | 4.4 | (2.2, 7.3) | 78 | 1.05 | 0.90, 1.21 | 1.07 | 0.88, 1.30 | |

| Fruit (servings/d) | ≥2 cups4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.1 | 0.6 | (0.1, 2.7) | 3 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.7 | 0.3 | (0, 1.9) | 1 | 0.55* | 0.40, 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.59, 1.08 | |

| 100% Fruit juice (servings/d) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.5 | 0.2 | (0, 1.4) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.6 | 0.3 | (0, 1.8) | — | 1.38 | 0.99, 1.91 | 1.44* | 1.00, 2.07 | |

| Vegetables (servings/d) | ≥2.5 cups4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.2 | 1.0 | (0.3, 2.5) | 0 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.9 | 0.7 | (0.1, 1.9) | 0 | 0.57* | 0.43, 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.55, 1.06 | |

| Potatoes (servings/wk) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 4.7 | 3.6 | (1.0, 9.9) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 5.1 | 4.0 | (1.1, 10.5) | — | 1.44* | 1.12, 1.86 | 1.56* | 1.18, 2.06 | |

| Eggs (servings/wk) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.6 | 0.8 | (0.1, 4.3) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.6 | 0.8 | (0.1, 4.3) | — | 1.15 | 0.94, 1.40 | 1.02 | 0.80, 1.29 | |

| Fish/shellfish (servings/wk) | ≥2 servings3 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2.2 | 1.7 | (0.6, 4.4) | 42 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.6 | 1.2 | (0.4, 3.1) | 25 | 0.92 | 0.75, 1.13 | 0.96 | 0.76, 1.21 | |

| Nuts/legumes/seeds (servings/wk) | ≥4 servings3 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 4.6 | 2.7 | (0.4, 11.3) | 37 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 3.4 | 1.7 | (0.3, 8.7) | 27 | 0.75* | 0.58, 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.71, 1.13 | |

| Red meat (servings/wk) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 4.0 | 3.5 | (1.3, 7.2) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 3.9 | 3.4 | (1.3, 7.1) | — | 1.67* | 1.26, 2.23 | 1.46* | 1.04, 2.06 | |

| Processed meat (servings/wk) | ≤2 servings3 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2.4 | 1.9 | (0.5, 4.9) | 53 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 2.5 | 2.0 | (0.6, 5.1) | 50 | 1.70* | 1.15, 2.52 | 1.17 | 0.75, 1.81 | |

| High-fat dairy products (servings/d) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.7 | 0.6 | (0.1, 1.6) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.8 | 0.6 | (0.1, 1.7) | — | 1.33 | 0.95, 1.86 | 1.43 | 0.98, 2.09 | |

| Low-fat dairy products (servings/d) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.2 | 0 | (0, 0.8) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.1 | 0 | (0, 0.3) | — | 0.59* | 0.45, 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.61, 1.09 | |

| Sweets and bakery desserts (servings/d) | ≤2.5 servings3 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.0 | 0.9 | (0.3, 2.0) | 17 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.8 | 0.6 | (0.2, 1.5) | 29 | 0.71* | 0.53, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.60, 1.12 | |

| Salty snacks (servings/d) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.4 | 0.3 | (0.1, 0.8) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.4 | 0.3 | (0.1, 0.8) | — | 1.25 | 0.91, 1.70 | 1.23 | 0.87, 1.74 | |

| Regular sodas (servings/wk) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 13.5 | 9.0 | (0.3, 32.8) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 15.8 | 11.4 | (0.4, 37.2) | — | 1.75* | 1.27, 2.40 | 1.25 | 0.92, 1.70 | |

| Diet sodas (servings/wk) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 3.3 | 0 | (0, 9.2) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 3.1 | 0 | (0, 7.5) | — | 0.83 | 0.71, 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.76, 1.08 | |

| Sports drinks and noncarbonated SSBs (servings/wk) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 4.0 | 1.8 | (0.2, 10.9) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 4.6 | 2.2 | (0.2, 12.4) | — | 1.36* | 1.05, 1.77 | 1.19 | 0.91, 1.55 | |

| All SSBs (servings/wk) | ≤4 servings4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 17.4 | 13.4 | (1.1, 38.7) | 23 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 20.0 | 16.1 | (1.7, 42.8) | 18 | 1.82* | 1.33, 2.49 | 1.21 | 0.86, 1.70 | |

| Water (servings/d) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.6 | 0.1 | (0, 5.7) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 2.1 | 0.2 | (0, 7.1) | — | 1.82* | 1.15, 2.90 | 1.57 | 0.92, 2.69 | |

| Nutrients | |||||||||

| Total energy (kcal/d) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2131 | 1771 | (635, 4064) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1979 | 1628 | (574, 3807) | — | 0.96 | 0.92, 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.06 | |

| EPA and DHA (g/d) | ≥0.5 g5 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.09 | 0.07 | (0.02, 0.19) | 0 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.08 | 0.06 | (0.02, 0.15) | 0 | 1.06 | 0.85, 1.32 | 0.97 | 0.74, 1.27 | |

| α-Linolenic acid (g/d) | ≥1.6 g (M), ≥1.1 g (F)6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.5 | 1.4 | (0.9, 2.1) | 55 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.3 | 1.2 | (0.7, 1.9) | 49 | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.94, 1.05 | |

| MUFA (% of energy) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 12 | 11.9 | (9.1, 14.9) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 12 | 11.9 | (9.1, 14.9) | — | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.05 | |

| PUFA (% of energy) | |||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 6.8 | 6.8 | (5.2, 8.6) | — | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 6.6 | 6.5 | (5.0, 8.3) | — | 0.97 | 0.93, 1.01 | 0.97 | 0.93, 1.02 | |

| SFA (% of energy) | <7% of energy3 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 10.5 | 10.4 | (7.4, 13.7) | 7 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 10.7 | 10.6 | (7.6, 13.9) | 6 | 1.04 | 0.98, 1.10 | 1.04 | 0.98, 1.10 | |

| Dietary cholesterol (mg/d) | <300 mg4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 283 | 261 | (138, 456) | 62 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 272 | 249 | (132, 440) | 65 | 1.09 | 0.98, 1.21 | 1.11 | 0.95, 1.28 | |

| Total fat (% of energy) | 20–35% of energy4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 32.2 | 32.2 | (25.1, 39.2) | 68 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 32.2 | 32.1 | (25.2, 39.3) | 68 | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.05 | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.05 | |

| Carbohydrates (% of energy) | 45–65% of energy4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 50.9 | 50.9 | (40.8, 61.1) | 73 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 51.6 | 51.5 | (41.4, 61.8) | 75 | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.04 | |

| Protein (% of energy) | 10–35% of energy4 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 14.6 | 14.4 | (10.9, 18.6) | 95 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 14.2 | 13.9 | (10.5, 18.0) | 93 | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.03 | |

| Folate (mg/d) | ≥320 mg6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 388 | 367 | (218, 583) | 64 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 335 | 314 | (184, 510) | 48 | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.95, 1.09 | |

| Dietary fiber (g/d) | ≥38 g (M, 20–50 y), ≥30 g (M, 51–65 y),≥25 g (F, 20–50 y), ≥21 g (F, 51–65 y)6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 15.8 | 14.8 | (8.3, 24.4) | 2 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 12.5 | 11.7 | (6.3, 19.9) | 0 | 0.88* | 0.82, 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.90, 1.08 | |

| Sodium (mg/d) | 1.5–2.3 g (20–50 y), 1.3–2.3 g (51–65 y)6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 3489 | 3374 | (2161, 4961) | 12 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 3132 | 3015 | (1899, 4511) | 19 | 0.98 | 0.93, 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.96, 1.09 | |

| Potassium (mg/d) | ≥4700 mg/d6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2656 | 2569 | (1639, 3780) | 2 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 2306 | 2219 | (1381, 3340) | 1 | 0.96* | 0.92, 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.08 | |

| Calcium (mg/d) | ≥800 mg (20–50 y), ≥800 mg (M, 51–65 y), ≥1000 mg (F,W 51–65 y)6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 823 | 770 | (434, 1279) | 44 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 727 | 676 | (375, 1143) | 33 | 0.96 | 0.90, 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.96, 1.11 | |

| Iron (mg/d) | ≥6 mg (M), ≥8.1 mg (F, 20–50 y), ≥5 mg (F, 51–65 y)6 | ||||||||

| Nonparticipants | 15.0 | 14.2 | (8.5, 22.5) | 99 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 13.1 | 12.3 | (7.3, 19.9) | 97 | 0.96 | 0.92, 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.95, 1.08 | |

SNAP participants (n = 924) were current program participants at the time of the survey. Nonparticipants (n = 2929) were low-income adults who had not received SNAP benefits within the previous 12 mo. *P < 0.05. 1 oz = 28 g; 1 cup = ∼240 mL for liquid and 150 g for dry foods (eg, fruit and vegetables). RD, relative difference; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; SSBs, sugar-sweetened beverages.

Multivariate linear regression models were adjusted for age, sex, race-ethnicity, place of birth, educational level, marital status, household size, health insurance, poverty income ratio, household food security, and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Recommended intake guideline from the 2006 American Heart Association.

Recommended intake guideline from the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Recommended intake guideline from the International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids.

Recommended intake guideline from the Dietary Reference Intakes, Adequate Intakes, or Estimated Average Requirements.

For nutrients, very few low-income adults met the guidelines for EPA and DHA (≥0.5 g/d), SFA (<7% of energy), dietary fiber (≥38 g/d for men aged 20–50 y, ≥30 g/d for men aged 51–65 y, ≥25 g/d for women aged 20–50 y, ≥21 g/d for women aged 51–65 y), sodium (1500–2300 mg/d for adults aged 20–50 y, 1300–2300 mg/d for adults aged 51–65 y), and potassium (≥4700 mg/d) (Table 2). Median intake of EPA and DHA ranged from 0.06 to 0.07 g/d. For SFAs, the mean intake was between 10.5% and 10.7% of total energy. Median intake of dietary fiber was between 11.7 and 14.8 g/d. Median sodium intake among low-income adults ranged from 3015 to 3374 mg/d, far exceeding the daily upper limit of 2300 mg. Median potassium intake was between 2219 and 2569 mg/d. For macronutrients, most low-income adults kept their intake within the recommended ranges for total fat, carbohydrate, and protein.

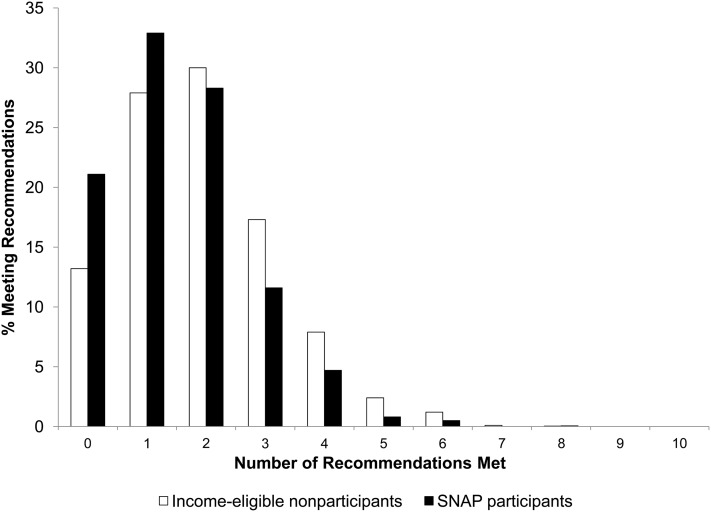

The proportion of low-income adults with daily dietary intakes meeting 10 food and nutrient guidelines aimed at promoting health is shown in Figure 1: whole grains (≥3 servings/d), fruit (≥4 servings/d), vegetables (≥5 servings/d), fish/shellfish (≥2 servings/wk), nuts/seeds/legumes (≥4 servings/wk), processed meats (<2 servings/wk), sugar-sweetened beverages (≤4 servings/wk), SFA (<7% of energy), sodium (1500–2300 mg/d for adults aged 20–50 y; 1300–2300 mg/d for adults aged 51–65 y), and potassium (≥4700 mg/d). Approximately 21% of SNAP participants and 13% of nonparticipants met zero of these food and nutrient guidelines with their daily dietary intakes. The proportion of low-income adults meeting ≥7 of these food and nutrient guidelines was virtually zero for both SNAP participants and nonparticipants.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of low-income SNAP participants (n = 924) and income-eligible nonparticipants (n = 2929) with daily dietary intakes meeting 10 food and nutrient guidelines. Recommendations included those for whole grains (≥3 servings/d), fruit (≥4 servings/d), vegetables (≥5 servings/d), fish/shellfish (≥2 servings/wk), nuts/seeds/legumes (≥4 servings/wk), processed meats (≤2 servings/wk), sugar-sweetened beverages (≤4 servings/wk), SFA (<7% energy), sodium (1500–2300 mg/d for ages 20–50 y, 1300–2300 mg/d for ages 51–65 y), and potassium (≥4700 mg/d). Recommendations for whole grains, fruit, vegetables, and sugar-sweetened beverages were taken from the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Recommendations for fish/shellfish, nuts/seeds/legumes, processed meats, and SFA were taken from the 2006 American Heart Association. Recommendations for sodium and potassium were taken from the Dietary Reference Intake's Estimated Average Requirements. SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Next, we sought to compare dietary intake by SNAP-participation status. After adjustment for differences in sociodemographic characteristics and household food security, SNAP participants consumed 39% fewer servings of whole grains (RD: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.43, 0.85), 44% more servings of 100% fruit juice (RD: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.00, 2.07; P = 0.048), 56% more servings of potatoes (RD: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.18, 2.06), and 46% more servings of red meat (RD: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.04, 2.06) than did nonparticipants. No significant differences in total energy or nutrient intake were observed between SNAP participants and nonparticipants.

After stratification by sex, race-ethnicity, and poverty level, similar dietary intakes were observed (see Tables S3–S5 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). Among men, women, non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Hispanics, and low-income adults at various poverty levels, SNAP participants and nonparticipants consumed few servings of whole grains, fruit, vegetables, fish/shellfish, and nuts/seeds/legumes. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages was high across all groups. For men, the mean weekly intake of sugar-sweetened beverages ranged from 20 to 21 servings (for women, 14–20 servings); for non-Hispanic whites, 18–23 servings; for blacks, 18 servings; for Hispanics, 16–17 servings; for adults between 0% and 50% of the FPL, 14–19 servings; for adults between 50% and 100% of the FPL, 21–22 servings; and for adults between 100% and 130% of the FPL, 19–20 servings. Some differences in sugar-sweetened beverages were observed by SNAP participation status. Among women, SNAP participants consumed 71% more servings of regular sodas (RD: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.14, 2.55) and 61% more servings of all sugar-sweetened beverages (RD: 1.61; 95% CI: 1.03, 2.52) than did nonparticipants. Among non-Hispanic whites, SNAP participants consumed 60% more regular sodas (RD: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.05, 2.42) than did nonparticipants. SNAP participation was also positively associated with water consumption among males (RD: 2.34; 95% CI: 1.30, 4.20) and blacks (RD: 2.77; 95% CI: 1.48, 5.20).

We examined the HEI-2005 (Table 3) and a modified AHEI (Table 4) as 2 measures of dietary quality. For the HEI-2005, SNAP participants and nonparticipants scored 44.4 and 47.9 points, respectively, out of a maximum 100 points. For both groups, the lowest component scores were for total fruit, whole fruit, dark-green and orange vegetables and legumes, and whole grains. The highest component scores were for total grains, meat, beans, and saturated fat. In comparison with nonparticipants, there were no significant differences in the HEI-2005 component scores or the total HEI-2005 score for SNAP participants. For the AHEI, low scores for several components were observed among both SNAP participants and nonparticipants: vegetables, fruit, nuts and soy protein, cereal fiber, multivitamin use, and alcohol. For both groups, the highest score was for the ratio of PUFAs to SFAs. After multivariate adjustment, SNAP participants had a 30% lower score for the white to red meat ratio (RD: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.99) than did nonparticipants. For SNAP participants and nonparticipants, the overall AHEI scores were 21.1 and 24.6 points, respectively, out of a maximum of 87.5 points. SNAP participants had an 8% lower AHEI total score (RD: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.87, 0.97) than did nonparticipants, after multivariate adjustment.

TABLE 3.

Participation in SNAP and dietary quality as measured by the Healthy Eating Index–20051

| Age- and sex-adjusted |

Multivariate-adjusted2 |

||||||

| Component | Standard for maximum score | Mean ± SD | % of maximum score | RD | 95% CI | RD | 95% CI |

| Total fruit (maximum score = 5) | ≥0.8 cup/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 34 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 30 | 0.62 | 0.32, 1.20 | 1.03 | 0.62, 1.70 | |

| Whole fruit (maximum score = 5) | ≥0.4 cup/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 32 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 22 | 0.40* | 0.26, 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.44, 1.08 | |

| Total vegetables (maximum score = 5) | ≥1.1 cup/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2.7 ± 0.0 | 54 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 50 | 1.01 | 0.84, 1.23 | 1.19 | 0.96, 1.47 | |

| Dark-green and orange vegetables and legumes (maximum score = 5) | ≥0.4 cup/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 18 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 14 | 0.62* | 0.41, 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.52, 1.27 | |

| Total grains (maximum score = 5) | ≥3.0 oz/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 4.3 ± 0.0 | 86 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 84 | 0.93 | 0.82, 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.82, 1.17 | |

| Whole grains (maximum score = 5) | ≥1.5 oz/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 12 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 10 | 0.51* | 0.31, 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.42, 1.23 | |

| Milk (maximum score = 10) | ≥1.3 cup/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 44 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 41 | 0.89 | 0.68, 1.17 | 1.13 | 0.86, 1.49 | |

| Meat and beans (maximum score = 10) | ≥2.5 oz/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 84 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 82 | 0.98 | 0.83, 1.14 | 0.98 | 0.83, 1.15 | |

| Oils (maximum score = 10) | ≥12 g/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 53 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 50 | 0.96 | 0.74, 1.24 | 1.11 | 0.83, 1.49 | |

| Saturated fat (maximum score = 10) | ≤7% of energy | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 73 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 72 | 1.03 | 0.77, 1.36 | 0.87 | 0.63, 1.20 | |

| Sodium (maximum score = 10) | ≤0.7 g/1000 kcal | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 54 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 54 | 1.28* | 1.00, 1.62 | 1.16 | 0.88, 1.53 | |

| Calories from SOFAAS (maximum score = 20) | ≤20% of energy | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 51 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 47 | 1.01 | 0.73, 1.40 | 1.15 | 0.81, 1.63 | |

| Total score | |||||||

| Nonparticipants | 47.9 ± 0.5 | 48 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 44.4 ± 0.6 | 44 | 0.94* | 0.91, 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.94, 1.02 | |

SNAP participants (n = 924) were current program participants at the time of the survey. Nonparticipants (n = 2929) were low-income adults who had not received SNAP benefits within the previous 12 mo. *P < 0.05. 1 oz = 28 g; 1 cup = ∼240 mL for liquid and 150 g for dry foods (eg, fruit and vegetables). RD, relative difference; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; SOFAAS, calories from solid fats, alcohol, and added sugars.

Multivariate linear regression models were adjusted for age, sex, race-ethnicity, place of birth, educational level, marital status, household size, health insurance, poverty income ratio, household food security, and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

TABLE 4.

Participation in SNAP and dietary quality as measured by a modified Alternate Healthy Eating Index1

| Age- and sex-adjusted |

Multivariate-adjusted2 |

||||||

| Component | Standard for maximum score | Mean ± SE | % of maximum score | 95% CI | RD | RD | 95% CI |

| Vegetables (maximum score = 10)3 | 5 servings/d | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 22 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 16 | 0.57* | 0.43, 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.55, 1.06 | |

| Fruit (maximum score = 10) | 4 servings/d | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 19 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 12 | 0.58* | 0.44, 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.62, 1.07 | |

| Nuts and soy protein (maximum score = 10) | 1 serving/d | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 23 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 16 | 0.71* | 0.54, 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.69, 1.09 | |

| Ratio of white to red meat (maximum score = 10) | ≥4:1 | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 33 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 28 | 0.8 | 0.58, 1.10 | 0.70* | 0.50, 0.99 | |

| Cereal fiber (maximum score = 10) | 15 g/d | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 15 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 13 | 1.03 | 0.77, 1.38 | 1.18 | 0.85, 1.64 | |

| Ratio of PUFAs to SFAs (maximum score = 10) | ≥1:1 | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 65 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 63 | 0.96 | 0.91, 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.90, 1.02 | |

| Multivitamin use (maximum score = 7.5) | Any use in past 30 d | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 3.3 ± 0.0 | 33 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 32 | 0.97 | 0.94, 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.95, 1.03 | |

| Alcohol (maximum score = 10) | 1.5–2.5 drinks (M), 0.5–1.5 drinks (F) | ||||||

| Nonparticipants | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 12 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0.75, 1.05 | 0.92 | 0.76, 1.10 | |

| Total score | |||||||

| Nonparticipants | 24.6 ± 0.4 | 28 | Reference | Reference | |||

| SNAP participants | 21.1 ± 0.5 | 24 | 0.86* | 0.81, 0.91 | 0.92* | 0.87, 0.97 | |

SNAP participants (n = 924) were current program participants at the time of the survey. Nonparticipants (n = 2929) were low-income adults who had not received SNAP benefits within the previous 12 mo. *P < 0.05. RD, relative difference; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Multivariate linear regression models were adjusted for age, sex, race-ethnicity, place of birth, educational level, marital status, household size, health insurance, poverty income ratio, household food security, and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Excluding potatoes.

DISCUSSION

Relative to national dietary guidelines, we found that low-income adults had low intakes of whole grains, fruit, vegetables, fish, and nuts/seeds/legumes and high intakes of processed meats, sweets and bakery desserts, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Although no low-income adults met most food and nutrient guidelines, a substantial proportion of SNAP participants and nonparticipants failed to meet any of these guidelines aimed at promoting health. When we examined dietary intake by SNAP-participation status, SNAP participants had several aspects of poorer dietary quality compared with income-eligible nonparticipants, including a higher consumption of fruit juice, potatoes, red meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages (in women); a lower consumption of whole grains; and a lower overall AHEI score.

These results are consistent with those of earlier studies that have examined SNAP participation and dietary intake. An analysis of the 1994–1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals showed that participation in the FSP was positively associated with the consumption of meats, added sugars, and total fat, although not with the consumption of fruit, vegetables, total grains, and dairy products (15). Using data from the 1999–2004 NHANES, the results of a 2008 USDA report suggested that adult FSP participants consumed significantly more calories from solid fats, alcohol, and added sugars than did income-eligible and higher-income nonparticipants (18). Although FSP participants had the lowest HEI-2005 score compared with the other nonparticipants, no significant difference in HEI-2005 was found between FSP participants and income-eligible nonparticipants. Most recently, our analysis of the 2007 California Health Interview Survey data found that SNAP participants had a significantly higher frequency of soda consumption than did eligible nonparticipants (10). This study builds on this work by examining additional foods, food groups, and nutrients and an alternative measure of dietary quality that has been related to weight management and chronic disease risk among adults (22, 28–31).

In our previous analysis of NHANES data, we found that SNAP participants had greater adiposity, including central adiposity, and higher prevalences of elevated triglycerides, lower HDL cholesterol, elevated fasting glucose, and the metabolic syndrome when compared with nonparticipants (14). These associations may be explained, in part, by the observed differences in dietary quality. High intakes of red meat and processed meats and a low consumption of poultry, fish, and nuts were previously linked to an elevated risk of coronary artery disease (32). Consumption of whole fruit and green leafy vegetables has been inversely associated with type 2 diabetes risk (33). In the same study, fruit juice consumption was positively associated with type 2 diabetes. In other recent studies, consumption of 1 to 2 servings of sugar-sweetened beverages daily was associated with higher risks of type 2 diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, and coronary artery disease (34, 35). The mean consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in the current analysis ranged from 17.4 to 20.0 servings/wk (2.5–2.9 servings/d). In comparison with the original report relating scores for the AHEI to risk of health outcomes, the mean AHEI scores for SNAP participants and nonparticipants fell within the range of the lowest quintile of dietary quality (22). Participants in the lowest AHEI quintile had a significantly higher risk of major chronic disease and cardiovascular disease than did participants in the highest AHEI quintile. Thus, although poor dietary quality of both SNAP participants and nonparticipants may be contributing to the elevated risks of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease among low-income adults, the adverse consequences may be more prominent among SNAP participants.

Researchers hypothesize that SNAP participation may influence dietary intake through increased food spending. In the 1990s, a series of “cash-out” experiments, through which a proportion of Food Stamp benefits was replaced with equivalent cash income, showed that in-home food expenditures were greater with Food Stamp benefits than with cash income (36–38). Given this increase in food expenditure, one might hypothesize that Food Stamps should lead to improved dietary quality. However, increasing evidence has shown that SNAP benefit allotments are too low to ensure meals consistent with the Thrifty Food Plan, a guideline from the USDA for nutritious, minimal-cost meals (39, 40). Rather than purchasing nutrient-rich fruit, vegetables, whole grains, or fish, which tend to be more expensive, low-income SNAP participants may tend to consume low-cost, nutrient-poor foods high in added fats and sugars, such as refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red or processed meats, to maximize their food budget (41, 42).

A recent Institute of Medicine report has highlighted the importance of aligning federal nutrition-assistance programs, such as SNAP, with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (43). Combined with public and private programs to improve fruit and vegetable access to SNAP participants, these efforts suggest that the program may be transitioning its focus from alleviating food insecurity to also promoting good nutrition for its beneficiaries (5, 44, 45). This study highlights the poor dietary quality of low-income Americans and emphasizes the gaps in dietary intake between SNAP participants and income-eligible nonparticipants. Future studies or proposals should continue to address the disparities in dietary intake by income level, but also attempt to improve multiple characteristics of dietary intake to enhance overall dietary quality among SNAP participants.

This study had several strengths and limitations. We had data for a large recently surveyed population that allowed for sufficient power to detect differences in dietary intake by SNAP participation status. Using the extensive dietary data collected in NHANES, we examined several foods, food groups, nutrients, and dietary patterns known to affect weight management and chronic disease development in adults. The availability of information on many sociodemographic characteristics and a validated food security measure also allowed us to adjust our RDs for key potential confounders.

However, the cross-sectional nature of NHANES makes it difficult to infer causation and to rule out confounding due to unmeasured differences still present between SNAP participants and nonparticipants, because the results show that SNAP participants endure greater hardships than do nonparticipants. Although this study attempted to control for measurable differences in socioeconomic status and food insecurity, residual confounding remains a possibility. Thus, we cannot determine the extent to which these associations may be explained by program participation. To examine the true effect of SNAP participation on dietary intake over time, longitudinal or intervention studies with strong dietary assessment methods are necessary to determine the extent to which these observed associations might be causal. Another limitation was that the prevalence of SNAP participation as estimated from NHANES is lower than the national estimate from the USDA. This may be attributable either to lower NHANES response rates among SNAP participants or to underreporting of SNAP participation (46). Factors related to misreporting SNAP participation include sex, marital status, and income level (47). Although this study accounts the effects of these variables, it is still possible that misclassification of SNAP exists. This misclassification may have biased our results toward the null because lower response rates among SNAP participants are likely among individuals with the lowest incomes and with potentially the poorest dietary quality. In addition, ∼11% of dietary recalls from individuals in the dietary subsample were missing. However, the NHANES dietary weights adjust for nonresponse of the dietary components; therefore, it is unlikely that this absence of data caused substantial bias in the results. Last, because dietary intake is the result of complex social, environmental, and behavioral forces—particularly in low-income communities—information on these factors associated with poor dietary quality would also enhance our knowledge of how SNAP influences dietary quality in the context of the external environment.

In conclusion, in this study, low-income adults were far from meeting recommended guidelines for whole grains, fruit, vegetables, fish, and nuts/seeds/legumes; many low-income adults exceeded recommended limits for processed meats, sweets and bakery desserts, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Virtually no low-income adults met most food and nutrient guidelines aimed at promoting health. Our results show that low-income adults receiving SNAP benefits have diets that are poorer in quality than those of income-eligible nonparticipants, which may contribute to the higher prevalences of obesity and obesity-related complications in this population. Given the recent focus of the program on nutrition, SNAP has the potential to influence the diets of millions of low-income Americans. Further considerations are warranted to determine how the current pilot programs to increase fruit and vegetable access and/or policy proposals to restrict sugar-sweetened beverages from the list of allowable foods in SNAP might eventually improve the dietary quality of all SNAP participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CWL, ELD, EBR, and WCW: designed the research; CWL and ELD: performed the statistical analysis; ELD, PJC, EV, EBR, and WCW: contributed to the interpretation of the data and made critical revisions to the manuscript for intellectual content; and CWL: drafted the manuscript and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors declared a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AHEI, Alternate Healthy Eating Index; FPL, federal poverty level; FSP, Food Stamp Program; HEI–2005, Healthy Eating Index–2005; NCI, National Cancer Institute; RD, relative difference; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.USDA FNS Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eligibility. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Food and Nutrition Services, US Department of Agriculture, 2011.

- 3.USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation and costs. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.USDA. USDA Food and Nutrition Service Program quick facts—Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2011.

- 5.USDA. SNAP name change. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2011.

- 6.Baum C. The effects of Food Stamps on obesity. Contractor and cooperator report, no. 34. Murfreesboro, TN: Middle Tennessee State University, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Yen ST, Eastwood DB. Effects of Food Stamp participation on body weight and obesity. Am J Agric Econ 2005;87:1167–73 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson D. Food stamp program participation is positively related to obesity in low income women. J Nutr 2003;133:2225–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones SJ, Frongillo EA. The modifying effects of Food Stamp Program participation on the relation between food insecurity and weight change in women. J Nutr 2006;136:1091–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung CW, Villamor E. Is participation in food and income assistance programmes associated with obesity in California adults? Results from a state-wide survey. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:645–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyerhoefer CD, Pylypchuk Y. Does participation in the Food Stamp Program increase the prevalence of obesity and health care spending? Am J Agric Econ 2008;90:287–305 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ver Ploeg M, Ralston K. Food Stamps and obesity: what do we know? EIB-34. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zagorsky JL, Smith PK. Does the U.S. Food Stamp Program contribute to adult weight gain? Econ Hum Biol 2009;7:246–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung CW, Willett WC, Ding EL. Low-income Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation is related to adiposity and metabolic risk factors. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:17–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilde PE, McNamara PE, Ranney CK. The effect on dietary quality of participation in the Food Stamp and WIC Programs. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, USDA, 2000 (Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report, no. 9)

- 16.Gleason P, Rangarajan A, Olson C. Dietary intake and dietary attitudes among food stamp participants and other low-income individuals. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research Inc, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox MK, Hamilton WL, Lin B-H. Effects of Food Assistance and Nutrition Programs on nutrition and health. Vol 3, Literature review. In: Fox MK, Hamilton WL, Lin B-H, eds. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, USDA, 2004. (Food Assistance and Nutrition research report, no. 19-3.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole N, Fox MK. Diet quality of Americans by Food Stamp participation status: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999-2004. Alexandria, VA: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.MEC. In-person dietary interviews procedure manual. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2002.

- 20.USDA. The USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 4.1. Documentation and user guide. Beltsville, MD: Food Surveys Research Group, Agricultural Research Service, USDA, 2010.

- 21.Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Reeve BB, Basiotis PP. Development and Evaluation of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. Washington, DC: Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, USDA, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCullough ML, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Diet quality and major chronic disease risk in men and women: moving toward improved dietary guidance. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:1261–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to measuring household food security. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.NCI Usual dietary intakes. The NCI method. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 25.NCI Usual dietary intakes. SAS macros for analysis of a single dietary component. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freedman LS, Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Krebs-Smith SM, Midthune D. The population distribution of ratios of usual intakes of dietary components that are consumed every day can be estimated from repeated 24-hour recalls. J Nutr 2010;140:111–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Ahuja J, Rhodes D, LaComb R. What we eat in America, NHANES 2005-2006: usual nutrient intakes from food and water compared to 1997 Dietary Reference Intakes for vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Washington, DC: Agricultural Research Service, USDA, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fung TT, Hu FB, Barbieri RL, Willett WC, Hankinson SE. Dietary patterns, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index and plasma sex hormone concentrations in postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer 2007;121:803–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2392–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fargnoli JL, Fung TT, Olenczuk DM, Chamberland JP, Hu FB, Mantzoros CS. Adherence to healthy eating patterns is associated with higher circulating total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin and lower resistin concentrations in women from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1213–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belin RJ, Greenland P, Allison M, Martin L, Shikany JM, Larson J, Tinker L, Howard BV, Lloyd-Jones D, Van Horn L. Diet quality and the risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Initiative (WHI). Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:49–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein AM, Sun Q, Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Willett WC. Major dietary protein sources and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation 2010;122:876–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazzano LA, Li TY, Joshipura KJ, Hu FB. Intake of fruit, vegetables, and fruit juices and risk of diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1311–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2477–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Koning L, Malik VS, Kellogg MD, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption, incident coronary heart disease and biomarkers of risk in men. Circulation 2012;125:1735–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fraker TM, Martini AP, Ohls JC. The effect of Food Stamp cashout on food expenditures: an assessment of the findings from four demonstrations. J Hum Resour 1995;30:633–49 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senauer B, Young N. The impact of Food Stamps on food expenditures: rejection of the traditional model. Am J Agric Econ 1986;68:37–43 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilde P, Ranney C. The distinct impact of Food Stamps on food spending. J Agric Resour Econ 1996;21:174–85 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose D. Food Stamps, the Thrifty Food Plan, and meal preparation: the importance of the time dimension for US nutrition policy. J Nutr Educ Behav 2007;39:226–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlson A, Lino M, Juan W, Hanson K, Basiotis PP. Thrifty Food Plan, 2006. Washington, DC: Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, USDA, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drewnowski A, Darmon N. The economics of obesity: dietary energy density and energy cost. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:265S–73S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drewnowski A, Darmon N. Food choices and diet costs: an economic analysis. J Nutr 2005;135:900–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Institute of Medicine Accelerating progress in obesity prevention. Solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 44.USDA Healthy Incentives pilot. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 45.USDA. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at farmer's markets: a how-to handbook. Washington, DC: USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, USDA Food and Nutrition Service, Project for Public Spaces, Inc, 2010.

- 46.Kissmer C. Reaching those in need: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation rates in 2007–summary. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 2009.

- 47.Bollinger CR, David MH. Modeling discrete choice with response error: Food Stamp participation. J Am Stat Assoc 1997;92:827–35 [Google Scholar]