Abstract

Background

Dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor, and rivaroxaban and apixaban, oral factor Xa inhibitors, have been found safe and effective in reducing stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. We sought to compare the efficacy and safety of the 3 new agents based on data from their published warfarin-controlled randomized trials, using the method of adjusted indirect comparisons.

Methods and Results

We included findings from 44,535 patients enrolled in three trials of the efficacy of dabigatran (RE-LY), apixaban (ARISTOTLE), and rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF), each compared with warfarin. The primary efficacy endpoint was stroke or systemic embolism; the safety endpoint we studied was major hemorrhage. To address a lack of comparability between trial populations caused by the restriction of ROCKET-AF to high risk patients, we conducted a subgroup analysis in patients with a CHADS2 score ≥3. We found no statistically significant efficacy differences among the three drugs, although apixaban and dabigatran were numerically superior to rivaroxaban. Apixaban produced significantly fewer major hemorrhages than dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Conclusion

An indirect comparison of new anticoagulants based on existing trial data indicates that in patients with a CHADS2 score ≥3 dabigatran 150mg, apixaban 5mg, and rivaroxaban 20 mg resulted in statistically similar rates of stroke and systemic embolism, but apixaban had a lower risk of major hemorrhage compared to dabigatran and rivaroxaban . Until head-to-head trials or large-scale observational studies that reflect routine use of these agents are available, such adjusted indirect comparisons based on trial data are one tool to guide initial therapeutic choices.

Keywords: Indirect comparison, anticoagulation, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, warfarin, randomized controlled trial

Background

Optimal clinical practice and coverage decision-making require assessment of the effectiveness and safety of new medications relative to existing treatments,1 but comparative information is often unavailable at the time of marketing authorization and initial use.2 Recently, Phase III trials have been completed comparing each of three new oral anticoagulants to warfarin in the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF).

Dabigatran, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, was more efficacious than warfarin in reducing the risk of stroke when given at a dose of 150mg b.i.d. to patients with non-valvular AF (hazard ratio [HR] = 066; 95% CI = 0.53 to 0.82).3 Rivaroxaban 20mg q.d.and apixaban 5mg b.i.d., both oral factor Xa inhibitors, were found to be non-inferior (rivaroxaban: HR=0.88; 0.74 to 1.03) and superior (apixaban: HR=0.79; 0.66 to 0.95) to warfarin, respectively, in intention-to-treat analyses. 4-5 Warfarin’s narrow therapeutic index and risk of interactions – both of which contribute to the need for frequent monitoring – make alternative agents appealing. These new agents also offer a welcome therapeutic option for patients ineligible for warfarin.6

In the absence of data from direct comparisons of the new anticoagulants, clinicians and payors attempting to engage in evidence-based decision making are likely to turn to qualitative comparisons of the results from the treatment arms of the three trials. Such comparisons may be helpful, or they may be may be inconclusive or misleading due to differences in trial design and patient populations 7. The formal method of adjusted indirect comparison, which compares treatment effects versus a common comparator, has been proposed as an alternative to simple, “naive” indirect comparisons.8 Two recent meta-analyses have compared results of adjusted indirect comparisons, such as ours, to subsequent direct comparisons. These meta-analyses have found the results of adjusted indirect and direct comparisons to be generally consistent, with “statistically” similar findings in 86%9 to 93%7 of cases.

In a recent indirect comparison of new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation10, the authors failed to assure comparability of trials, as ROCKET-AF required a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher while the other trails also included patients with scores of 0 and 1. Since CHADS2 is a strong predictor of the primary endpoint in all trials, findings of such an indirect comparison are likely confounded. They further violated the comparability of trials by contrasting the major bleed rates from an ITT analysis of RE-LY to the results from the on-treatment analyses of ARISTOTLE and ROCKET-AF. We conducted an adjusted indirect comparison using available clinical trial data on the three new anticoagulants, with warfarin as a common reference treatment. To overcome limitations of the previous study, we abstracted additional data so as to compare more similar analyses and patient populations.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed and clinicaltrials.gov in October 2011 for all Phase III randomized controlled trials of patients receiving apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran versus warfarin (the only studied common comparison treatment) for the prevention of thrombotic events in atrial fibrillation. We restricted our analysis to studies reporting event rates, or containing sufficient data to calculate event rates. We also searched FDA advisory committee briefing materials and approval packages for any relevant supplemental data on dabigatran and rivaroxaban; apixaban has not yet been reviewed by FDA for the indication of prophylaxis in AF.

Data abstraction

Data were abstracted independently by two authors for a primary efficacy endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism, a secondary efficacy endpoint of all-cause mortality, and the safety outcome of major hemorrhage. We identified intention-to-treat as the appropriate analytical strategy as this approach preserves the random treatment assignment within an RCT. In addition to endpoints, we abstracted data on inclusion and exclusion criteria, endpoint definitions, risk factors for stroke in the warfarin control groups, and study design and analysis in order to assess the comparability of the trials.

Analysis

We performed comparisons across the trials using Bucher’s method,8,11 an adjusted indirect comparison approach that analyzes the magnitude of relative treatment effects against a common comparator rather than absolute event rates in individual study arms to estimate the comparative safety and efficacy of two or more treatments. We used this approach to compare relative event rates among patients treated with apixaban, dabigatran (150mg), and rivaroxaban versus warfarin. We focused on dabigatran 150, the formulation approved in the United States, but also assessed the comparative safety and efficacy of dabigatran 110 mg in a secondary analysis, as this formulation may be of interest outside the US. Bucher’s method rests on the assumption that the trials, or subgroups within trials, are sufficiently similar with respect to potential clinical and methodological modifiers of relative treatment effects, such as patient characteristics, intervention characteristics, follow-up time, outcome definitions and ascertainment (“clinical moderators”) and randomization and blinding (“methodological moderators”). We assessed the validity of this assumption by evaluating the level of clinical and methodologic similarity among the clinical trials and by comparing outcome event rates among warfarin-treated control patients across the different trials to assess treatment effectiveness in the common referent group. Because the majority of patients in ROCKET-AF had CHADS2 scores of ≥3, we compared rivaroxaban to apixaban and dabigatran in an analysis restricted to this population.12

Results

We included findings from 44,535 patients with AF enrolled in three randomized trials comparing the efficacy of dabigatran 150mg b.i.d.(RE-LY),4,13 rivaroxaban 20mg q.d. (ROCKET-AF),5 and apixaban 5mg b.i.d. (ARISTOTLE),6 to warfarin. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were generally similar across trials, except that ROCKET-AF participants were required to have a CHADS2 score ≥2; this was reflected in the higher proportions of patients with stroke risk factors in both the rivaroxaban and the warfarin control groups of ROCKET-AF (Table 1). The trial populations were similar in age, gender distribution, systolic blood pressure, and prevalence of a history of myocardial infarction at baseline. A higher proportion of warfarin-treated patients in RE-LY were classified as having paroxysmal AF (33.8%) than those in ARISTOTLE (15.5%) or ROCKET-AF (17.8%). Prior vitamin K antagonist use was more common in warfarin users in ROCKET-AF (62.5%) than in those in ARISTOTLE (57.2%) or RE-LY (48.6%).

Table 1.

Selected patient characteristics in the warfarin control groups of the RE-LY (dabigatran vs. warfarin), ARISTOTLE (apixaban vs. warfarin), and ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban vs. warfarin) trials.

| ARISTOTLE | RE-LY | ROCKET AF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin group (N=9081) |

Warfarin group (N=6022) |

Warfarin group (N=7133) |

|

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Age, median (IQR) or mean±sd | 70 (63-76) | 71.6±8.6 | 73 (65-78) |

| Female, % | 35.0 | 36.7 | 39.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR) or mean±sd | 130 (120-140) | 131.2±17.4 | 130 (120-140) |

| Weight in kg, median (IQR) or mean±sd | 82 (70-95) | 82.7±19.7 | NR |

| Prior myocardial infarction, % | 13.9 | 16.1 | 18.0 |

| Prior spontaneous or clinically relevant bleeding, %a | 16.7 | NR | NR |

| Type of atrial fibrillation, % | |||

| Newly diagnosed | NR | NR | 1.4 |

| Paroxysmal | 15.5 | 33.8 | 17.8 |

| Persistent / permanent | 84.4 | 66.1 | 80.8 |

| Prior use of vitamin K antagonist, %b | 57.2 | 48.6 | 62.5 |

| Prior aspirin use, % | 30.5 | 40.6 | 36.7 |

| Stroke risk factors | |||

| Prior stroke / TIA / systemic embolism, % | 19.7 | 19.8 | 54.6 |

| Heart failure or reduced ejection fraction, % | 35.4 | 31.9 | 62.3 |

| Diabetes, % | 24.9 | 23.4 | 39.5 |

| Hypertension, % | 87.6c | 78.9 | 90.8 |

| CHADS2 score | |||

| Mean±sd | 2.1±1.1 | 2.1±1.1 | 3.5±1.0 |

| ≤1, % | 34.0 | 30.9 | 0.0 |

| 2, % | 35.8 | 37.0 | 13.1 |

| ≥3, % | 30.2 | 32.1 | 86.9 |

| Target INR for warfarin group | 2-3 | 2-3 | 2-3 |

| Mean time in target INR range | 62% | 64% | 55% |

| Warfarin management, blinding | Blinded dose adjustment algorithm |

Unblinded dose adjust- ment with advice on INR control |

Blinded INR values provided |

| Median follow-up, years | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| Double-blinded | yes | nod | yes |

IQR, interquartile range; sd, standard deviation; NR, not reported

RE-LY and ROCKET AF excluded patients with recent gastrointestinal bleeding or a history of intracranial, intraocular, spinal, retroperitoneal or atraumatic intra-articular bleeding

In ARISTOTLE, prior vitamin K antagonist use was defined as use >30 consecutive days; in RE-LY it was defined as lifetime use of 61 days or more; the definition was not reported in the ROCKET AF publication

Defined as hypertension requiring treatment

Warfarin was given in an unblinded manner

Stroke or systemic embolism was the primary efficacy endpoint in all three trials. Major bleeding was defined consistently across trials as clinically overt bleeding that occurred at a critical site or bleeding that was accompanied by a drop in hemoglobin of at least 2 g/dL or transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red cells, or death. Major bleeding was the primary safety outcome in ARISTOTLE and RE-LY and was a component of the primary safety outcome of major or non-major clinically relevant bleeding in ROCKET-AF. Primary efficacy data were analyzed according to an intention-to-treat principle in all trials, although the ITT analysis was reported as a secondary analysis in ROCKET-AF. Only RE-LY reported results from an ITT analysis as the primary safety analysis; as-treated results were available from all trials. 2-year treatment discontinuation rates in RE-LY were 20.7% for 110 mg dabigatran, 21.2% for 150 mg dabigatran, and 16.6% for warfarin; 2 year discontinuation rates in ROCKET-AF were 34.7% for rivaroxaban and 33.5% for warfarin; and total discontinuation rates in ARISTOTLE were 25.3% for apixaban and 27.5% for warfarin.

The trials differed in blinding and in warfarin dosing. ROCKET-AF investigators were blinded to anticoagulation group assignment and were provided with real (warfarin arm) or sham (rivaroxaban arm) INR values; ARISTOTLE investigators were similarly blinded to group assignment and were provided with a blinded dose adjustment algorithm14 and feedback. By contrast, RE-LY investigators were unblinded to warfarin-group status, regulating its dose with advice on INR control. During the trials, INR control was better in the warfarin arms of ARISTOTLE (62% mean time in therapeutic range [TTR]) and RE-LY (64% TTR) than in ROCKET-AF (55% TTR). The stroke and embolism event rate was substantially higher in the warfarin arm of ROCKET-AF (2.42 per 100 patient-years; estimated 95% CI: 2.16 to 2.71) compared to that arm in RE-LY (1.71 per 100 patient-years; estimated 95% CI: 1.49 to 1.96) or ARISTOTLE (1.60 per 100 patient-years; estimated 95% CI: 1.42 to 1.80) (Table 2). These differences were not present when patients with CHADS2 scores ≥3 were compared (Table 3).

Table 2.

Users of dabigatran (RE-LY*), apixaban (ARISTOTLE), and rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) and rates of stroke and systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, death of any cause, and major hemorrhage compared with warfarin.

| New anticoagulant | Warfarin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Subjects | Events | Event rate per 100 person- years |

Subjects | Events | Event rate (95% CI) per 100 person-years† |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Primary efficacy endpoint: stroke or systemic embolism (intention-to-treat analysis) | |||||||

| Apixaban (ARISTOTLE) | 9,120 | 212 | 1.27 | 9,081 | 265 | 1.60 (1.42, 1.80) | 0.79 (0.66, 0.95) |

| Dabigatran 110mg (RE-LY) | 6,015 | 183 | 1.54 | 6,022 | 202 | 1.71 (1.49, 1.96) | 0.90 (0.74, 1.10) |

| Dabigatran 150mg (RE-LY) | 6,076 | 134 | 1.11 | 0.66 (0.52, 0.81) | |||

| Rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) ‡ | 7,081 | 269 | 2.12 | 7,090 | 306 | 2.42 (2.16, 2.71) | 0.88 (0.75, 1.03) |

| Death of any cause (intention-to-treat analysis) | |||||||

| Apixaban (ARISTOTLE) | 9,120 | 603 | 3.52 | 9,081 | 669 | 3.94 (3.65, 4.25) | 0.89 (0.80, 1.00) |

| Dabigatran 110mg (RE-LY) | 6,015 | 446 | 3.75 | 6,022 | 487 | 4.13 (3.78, 4.51) | 0.91 (0.80, 1.03) |

| Dabigatran 150mg (RE-LY) | 6,076 | 438 | 3.64 | 0.88 (0.77, 1.00) | |||

| Rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) ‡ | 7,081 | 582 | 4.5d | 7,090 | 632 | 4.9§ (4.53, 5.29) | 0.92 (0.82, 1.03) |

| Major Hemorrhage (on-treatment analysis) | |||||||

| Apixaban (ARISTOTLE) | 9,088 | 327 | 2.13 | 9,052 | 462 | 3.09 (2.82, 3.38) | 0.69 (0.60, 0.80) |

| Dabigatran 110mg (RE-LY) ∥ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.83 (0.71, 0.96) |

| Dabigatran 150mg (RE-LY) ∥ | NR | NR | NR | 0.98 (0.85, 1.14) | |||

| Rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) ¶, ** | 7,111 | 395 | 3.60 | 7,125 | 386 | 3.45 (3.12, 3.81) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) |

CI, confidence interval; NR, not reported

Includes updated data published by Connolly et al. in N Engl J Med, 2010.13

95% confidence intervals were estimated using the method for person-time data described in Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Introduction to categorical statistics. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;, 2008:253-254. We estimated person-time by dividing the number of events by the event rate15.

The primary analysis in ROCKET-AF was “per-protocol”, restricted to subjects who received at least one study dose followed through 2 days after the last dose. The intention-to-treat analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint and death presented here were published as secondary analyses.

Mortality rates in ROCKET-AF were published to only one decimal point.

The published RE-LY safety analysis was intention-to-treat (hazard ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.81, 1.07 for dabigatran 150mg and hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.69, 0.93 for dabigatran 110mg). Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the on-treatment analysis were presented in the FDA Advisory Committee briefing documents.16

In ROCKET-AF major bleeding was a component of the primary safety outcome: major and clinically relevant non-major bleeding.

For the ROCKET-AF trial the number of subjects is greater in the on-treatment safety analysis than in the intention-to-treat efficacy analysis because the latter excluded data on 93 patients (50 in the rivaroxaban group and 43 in the warfarin group) due to violations in Good Clinical Practice guidelines at one participating site.

Table 3.

Primary efficacy and safety in subgroups of trial patients with CHADS2 score ≥3.

| New anticoagulant | Warfarin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New anticoagulant | |||||||

| Subjects | Events | Event rate per 100 person- years |

Subjects | Events | Event rate (95% CI) per 100 person-years* |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Primary efficacy endpoint: stroke or systemic embolism (intention-to-treat analysis) | |||||||

| Apixaban (ARISTOTLE) | 2,758 | 94 | 1.9† | 2,744 | 132 | 2.8† (2.35, 3.31) | 0.68 (0.52, 0.88) |

| Dabigatran 110mg (RE-LY) ‡ | 1,968 | 82‡ | 2.12 | 1,933 | 101§ | 2.68 (2.19, 3.24) | 0.79 (0.59, 1.05)∥ |

| Dabigatran 150mg (RE-LY) ‡ | 1,981 | 74‡ | 1.88 | 1,933 | 101§ | 2.68 (2.19, 3.24) | 0.70 (0.52, 0.95)∥ |

| Rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) ¶ | 6,156 | 239 | 2.25 | 6,155 | 270 | 2.56 (2.27, 2.88) | 0.88 (0.74, 1.05) |

| Major Hemorrhage (on-treatment analysis) | |||||||

| Apixaban (ARISTOTLE) | NR** | 126 | 2.9† | NR** | 173 | 4.2† (3.61, 4.86) | 0.69 (0.55, 0.87) |

| Dabigatran 110mg (RE-LY) approximated†† |

1966 | 147 | 3.80 | 1931 | 172 | 4.61 (3.96, 5.34) | 0.82 (0.66, 1.03)∥ |

| Dabigatran 150mg (RE-LY) approximated†† |

1979 | 188 | 4.86 | 1931 | 172 | 4.61 (3.96, 5.34) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.30)∥ |

| Rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) ‡‡ | 6187 | 337 | 3.64 | 6191 | 337 | 3.60 (3.23, 4.00) | 1.01 (0.87, 1.18) |

CI, confidence interval; NR, not reported

95% confidence intervals were estimated using the method for person-time data described in Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Introduction to categorical statistics. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:253-254. We estimated person-time by dividing the number of events by the event rate15.

Event rates in ARISTOTLE were published to only one decimal point.

This analysis does not include the updated data published by Connolly et al. in N Engl J Med, 2010 as subgroup-specific data were not reported13.

The number of events in this subgroup were not reported in RE-LY; we estimated these by multiplying the number of subjects by the median follow-up time (2.0 years) and then multiplying this by the event rate.

Confidence intervals around the hazard ratio for RE-LY were estimated using the mid-P-value function described in Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Introduction to categorical statistics. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:253-254. We estimated person-time by dividing the number of events by the event rate15.

The primary analysis in ROCKET-AF was “per-protocol”, restricted to subjects who received at least one study dose followed through 2 days after the last dose. The intention-to-treat analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint presented here was published as a secondary analysis.

The number of subjects included in the on-treatment analysis was not presented in the publication.

An on-treatment analysis was not reported for subgroups within RE-LY. The numbers presented here are from the intention-to-treat analysis presented in the FDA Advisory Committee briefing documents.16

For the ROCKET-AF trial the number of subjects is greater in the on-treatment safety analysis than in the intention-to-treat efficacy analysis because the latter excluded data on 93 patients (50 in the rivaroxaban group and 43 in the warfarin group) due to violations in Good Clinical Practice guidelines at one participating site.

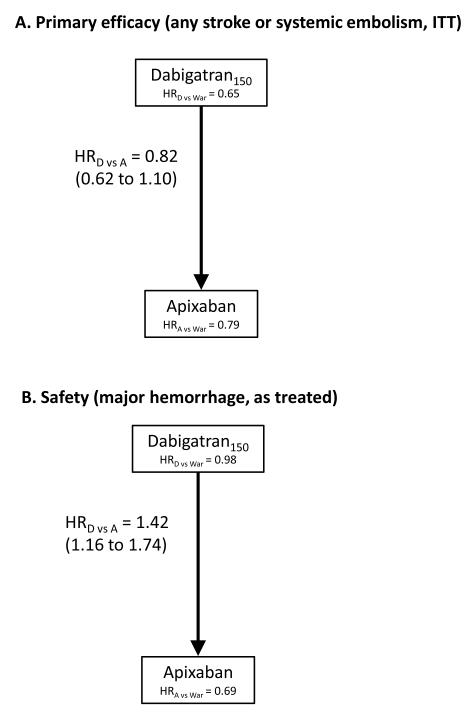

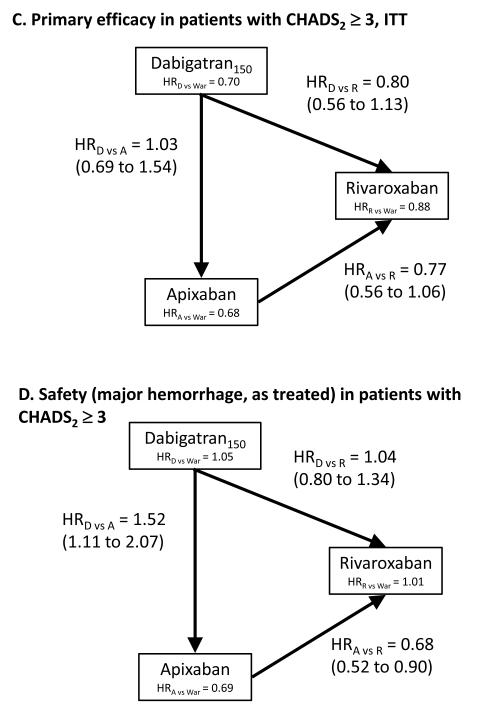

Due to increased baseline stroke risk among the participants of ROCKET-AF compared with ARISTOTLE and RE-LY, we conducted two analyses: 1) an indirect comparison of apixaban and dabigatran among all participants, and 2) a comparison of all three agents in participants with a CHADS2 score ≥3. In adjusted indirect comparisons of the overall trial populations (Figure 1a), we found no significant differences in the rate of stroke or systemic embolism between dabigatran and apixaban. Apixaban was associated with a 30% lower rate of major hemorrhage than dabigatran (HR: 0.70; 0.57 to 0.86) (Figure 1b). There were no significant differences among the agents in all-cause mortality (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The relative efficacy and safety of dabigatran (150mg), apixaban, and rivaroxaban from adjusted indirect comparisons of three randomized trials. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The agent at the head of the arrow is the referent agent (i.e. the denominator term).

In subgroups of patients with CHADS2 scores ≥3, which ensured fairer and less confounded comparisons among rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran concerning baseline stroke risks, both dabigatran and apixaban reduced the risk of stroke and embolism by about 20% in comparison to rivaroxaban, without reaching statistical significance (Figure 1c). In the same subgroup the risk of major hemorrhage was again lowest for apixaban compared to both other drugs (Figure 1d).

A secondary analysis comparing dabigatran 110 mg to apixaban among all subjects and to rivaroxaban among the subgroup of patients with CHADS2 scores ≥3 found no significant differences between agents in efficacy or risk of major hemorrhage (Appendix).

Discussion

Formal adjusted indirect comparisons of randomized trials can be a useful tool to estimate the comparative efficacy of newly marketed medications before any head-to-head trials or pharmacoepidemiologic studies become available, if certain study characteristics are met. We compared all subjects in ARISTOTLE and RE-LY anticoagulant trials, as well as patients with an elevated risk for stroke (CHADS2 ≥3), to make the results of one trial (ROCKET-AF) more comparable. Among all participants, apixaban had a lower risk of major bleeding than dabigatran with no significant differences in efficacy. Among patients with CHADS2 ≥3, dabigatran and apixaban trended towards greater efficacy than rivaroxaban, but the differences were not significant. Major bleeding risk on apixaban was significantly less than that on rivaroxaban or dabigatran.

We used intention-to-treat results for efficacy endpoints and on-treatment analyses for safety endpoints. Intention-to-treat is arguably the preferred approach for analyzing data from an RCT as it preserves random treatment assignment. The lack of complete intention-to-treat safety data from ARISTOTLE and RE-LY is a limitation. The use of an on-treatment approach with a short risk window of only two days after the last dose anticoagulant for the safety analysis raises the possibility that bleeding events attributable to anticoagulant use that manifest after two days would have been missed. In RE-LY, where an ITT analysis was reported as the primary safety analysis, the ITT hazard ratio for major bleeding for 110 mg dabigatran compared to warfarin was 0.80 (95% CI: 0.69 – 0.93) versus 0.83 (95% CI: 0.71 – 0.96) for an on-treatment analysis; for 150 mg dabigatran, the ITT hazard ratios as 0.93 (0.81 – 1.07) versus 0.98 (0.85 – 1.14) on-treatment. ARISTOTLE reported a 27% reduction in major bleeding from a secondary ITT analysis compared to a 31% reduction in an on-treatment analysis.

Bucher’s method of adjusted indirect comparisons assumes that the trials are sufficiently similar to one another in terms of potential modifiers of treatment effects, such that the relative efficacy of a given treatment compared to a common comparator would be homogeneous across each of the study populations. This assumption was likely violated for ROCKET-AF, which was restricted to patients with a CHADS2 score of ≥2, and therefore restricted our comparisons of rivaroxaban to subgroups with CHADS2 scores ≥3. Reassuringly, event rates in the warfarin comparison groups of all three trials among this subgroup were similar. However, it is still possible that other factors, such as the poorer INR control in the warfarin arm of ROCKET-AF, could threaten the validity of our analysis. While primary outcome event rates were similar among warfarin-treated patients across trials, the major hemorrhage rate was slightly lower among warfarin-treated patients in the ROCKET-AF trial as compared to other trials, raising the possibility that another unobserved factor could influence our results. Data on the baseline characteristics of the subgroups with CHADS2 scores ≥3 were not available, precluding further evaluation of differences in baseline risk.

In addition to clinical similarity, Bucher’s method requires methodological similarity. Biases inherent to each of the trials may cause indirect comparisons to be biased unless trials are all biased in the same direction and to the same extent. It is not possible to predict the direction and magnitude of bias in specific instances. While blinding generally reduces bias, the lack of blinding in RE-LY may have resulted in its greater TTR on warfarin, thus increasing the apparent relative effectiveness of warfarin compared to dabigatran. Lack of complete blinding can have a smaller effect on endpoint ascertainment if objectively measured endpoints are of interest, as in our study.17

Our analysis was limited by the available RCT data. Apixaban has not yet been reviewed by FDA for the indication of thromboembolic event prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation, and thus advisory committee briefing materials are not yet available. Rivaroxaban has not been evaluated in lower-risk patients, and while it was possible to compare rivaroxaban to apixaban and dabigatran in patients with CHADS2 ≥3, this restriction resulted in reduced statistical power.

Adjusted indirect treatment comparisons such as ours generally produce reliable estimates. A recent study found that results of indirect and head-to-head comparisons were statistically similar in 86% of 112 analyses, which covered a wide range of clinical indications, and in only one case (<1%) were the indirect comparison results statistically significant and in the opposite direction of the corresponding head-to-head comparison results.9 Statistically inconsistent findings were more common when fewer trials were available,outcomes were subjective, and a statically significant treatment effect was found by either the direct or indirect comparison. Indirect comparisons were less likely to find statistically significant differences between treatments than direct comparisons, which are four times as precise for the same sample size. 9 Power was further limited in our analysis since we focused on a high-risk patient subgroup in order to enhance comparability across trials. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating clinical and methodological similarity when conducting indirect comparisons, as we have done,18 and following up initial pre-approval trials with rigorously conducted observational studies, which can provide direct comparisons in large populations.19

Optimal clinical practice and policy making require assessing the comparative effectiveness of newly approved medications as soon as possible after their market authorization. The three new oral anticoagulants that we compared have all been found to be superior or at least non-inferior to warfarin in large randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with AF, and they may be particularly good options for patients ineligible for warfarin or for whom INR monitoring cannot be performed adequately. The differences we found among the new anticoagulants, and between each of them and warfarin, are modest in scale compared to the substantial differences in outcome between no anticoagulant and any anticoagulant in AF patients.

In the absence of head-to-head comparisons from randomized trials, or effectiveness studies using routine care data, adjusted indirect comparisons using data from RCTs can provide useful approximations for clinical decision makers, information which can be generated even before a drug is authorized for marketing for a given indication, as with apixaban. By supplementing data published in the medical literature with data from FDA advisory committee briefing documents for dabigatran and rivaroxaban, examining results from secondary and subgroup analyses to increase comparability across trials in study designs and populations, performing a quantitative evaluation, and highlighting differences between the trials, our analysis provides an improvement over the qualitative comparisons that decision makers may undertake, which may be inconclusive or misleading due to differences in trial design. Failure to insure comparable populations may bias results.10 However, the fact that apixaban has not yet been reviewed by FDA for the indication of stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation limits the availability of supplemental data for this particular agent. In the case of the new anticoagulants, our understanding of the relative effectiveness and safety of these drugs may well change in the context of routine care depending on actual adherence patterns, baseline risks of patients who are prescribed these drugs outside of trial criteria, and other “real-world” differences that may not be predicted by trial results. Follow-up active observational studies that monitor the comparative safety and effectiveness of newly marketed drugs using health care claims data can then provide such followup information in a timely manner.1 Because such studies can themselves take some time to organize and conduct, rigorous comparisons of existing trial data – if feasible and responsibly conducted – may offer the best basis for evidence-based decision-making when new drugs are first brought to market.

Supplementary Material

What is known

Dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor, and rivaroxaban and apixaban, oral factor Xa inhibitors, have been found safe and effective in reducing stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation compared to warfarin.

In the absence of data from direct comparisons of these new anticoagulants, adjusted indirect comparison can be used to compare treatment effects using warfarin as a common comparator group.

What this article adds

Patients in 3 major warfarin-controlled randomized trials were comparable when limited to those with a CHADS2 score of 3 or higher.

We found no statistically significant differences among the three drugs in their efficacy in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, although apixaban and dabigatran were numerically superior to rivaroxaban.

Apixaban produced statistically significantly fewer major hemorrhages than dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Funded by the National Library of Medicine (RO1-LM010213), the National Center for Research Resources (RC1-RR028231) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (RC4-HL106373).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Schneeweiss is Principal Investigator of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital DEcIDE Center on Comparative Effectiveness Research and the DEcIDE Methods Center both funded by AHRQ and of the Harvard-Brigham Drug Safety and Risk Management Research Center funded by FDA. Dr. Schneeweiss is paid consultant to the consulting firms WHISCON and Booz & Co. Dr. Schneeweiss is principal investigator of investigator-initiated grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics from Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer-Ingelheim on unrelated topics but not on any medications discussed in this paper.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schneeweiss S, Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Ruhl M, Rassen JA. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of newly marketed medications: methodological challenges and implications for drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:777–90. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg NH, Schneeweiss S, Kowal MK, Gagne JJ. Availability of comparative efficacy data at the time of drug approval in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:1786–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittkowsky AK. Effective anticoagulation therapy: defining the gap between clinical studies and clinical practice. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:S297–306. discussion S12-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;326:472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683–91. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song F, Xiong T, Parekh-Bhurke S, et al. Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of competing interventions: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lip GYH, Larsen TB, Skjøth F, Rasmussen LH. Indirect comparisons of new oral anticoagulant drugs for efficacy and safety when used for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells GASS, Chen L, Khan M, Coyle D. Indirect Evidence: Indirect Treatment Comparisons in Meta-Analysis Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2009.

- 12.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Reilly PA, Wallentin L. Newly identified events in the RE-LY trial. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1875–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1007378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ROCKET-AF_Study_Investigators Rivaroxaban-once daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation: rationale and design of the ROCKET AF study. Am Heart J. 2010;159:340–7. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenland SRK. Introduction to categorical statistics. In: Rothman KJGS, Lash TL, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. pp. 253–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehringer Ingelheim Advisory Committee Briefing Document: Dabigatran Etexilate (DE), DE 150 BID and DE 110 BID. 2010.

- 17.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008;336:601–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song F, Harvey I, Lilford R. Adjusted indirect comparison may be less biased than direct comparison for evaluating new pharmaceutical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:455–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avorn J. In defense of pharmacoepidemiology--embracing the yin and yang of drug research. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2219–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0706892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.