Abstract

Parentification of children has not been the focus of much empirical research. Consequently, this study was designed to explore the defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden in a sample of 356 children living in urban poverty. In a series of multivariate analyses, characteristics of the children, vocational-educational status of their mothers, and family structure correlated with caretaking burden more consistently than psychiatric, substance use, or personality problems in the mothers. Moreover, responsibility to care for mother, more so than responsibility for household chores or the care of siblings, consistently correlated with the psychosocial adjustment of the children. However, even the highest levels of caretaking burden were not consistently associated with clinically significant compromise of psychosocial adjustment.

Keywords: parent-child relations, caregiver burden, dysfunctional family, childhood development

For more than 30 years, family systems theory has highlighted the relationship between disturbance in family functioning and the parentification of children. Building largely upon the work of Boszormenyi-Nagy and Spark (1973), clinicians and researchers have defined parentification as a family process involving developmentally inappropriate expectations that children function in a parental role within stressed, disorganized family systems (Chase, 1999; Jurkovic, 1997). The process is characterized by a reversal of roles such that children must defer their developmental needs to accommodate the needs of their parents for instrumental or emotional support (Chase, 1999). Typically, the process involves unreasonable expectations that children manage the household, care for younger siblings, or care for an adult in the role of parent, spouse, or peer (Chase, 1999; Jurkovic, 1997).

Despite longstanding interest in the concept of parentification as a clinical phenomenon, empirical research on the topic did not begin until very recently (Earley & Cushway, 2002). At this time, there is accumulating evidence that parentification does occur within family systems stressed by alcoholism, drug abuse, divorce, physical disability, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and persistent neglect (Bekir, McLellan, Childress, & Gariti, 1993; Godsall, Jurkovic, Emshoff, Anderson, & Stanwyck, 2004; Hetherington, 1999; Jurkovic, Thirkield, & Morrell, 2001; Koerner, Wallace, Lehman, Lee, & Escalante, 2004; Macfie et al., 1999; Stein, Riedel, & Rotheram-Borus, 1999). There is also evidence that parentification occurs within stressed family systems across generations (Bekir et al., 1993; Jacobvitz, Morgan, Kretchmar, & Morgan, 1991; Macfie, McElwain, Houts, & Cox, 2005), and although the finding has not been entirely consistent, mothers may be more likely than fathers to involve children in reversal of parent–child roles (Hetherington, 1999; Mayseless, Bartholomew, Henderson, & Trinke, 2004).

Caretaking, Family Process, and Child Development

Although parentification has been frequently associated with disturbance in family functioning, researchers have also highlighted ways in which it may represent a distortion of normative process involving reciprocity in caregiving relationships within supportive family systems (e.g., see Jurkovic, 1997). In many circumstances, concern about parental figures, expectations that children help with household chores, and involvement in the care of younger children is normative. In particular, the extent to which children are expected to assist their parents may vary with cultural context (Jurkovic, 1997; Jurkovic et al., 2004), and time-limited involvement in caretaking activity may be a benign, adaptive response to a family crisis (Jurkovic, 1997). When present within a family system that offers support and recognition, expectations that children help with household chores or the care of younger children, rather than being detrimental, may actually promote self-esteem, capacity for empathy, and a sense of altruism (Jurkovic, 1997).

Differential Risk Associated With Different Dimensions of Caretaking

Moreover, different forms of caretaking may represent differential risk for poor developmental outcomes. That is, involvement in some forms of caretaking may be more noxious for children than others. Historically, clinicians and researchers have expressed concern about distortion of parent–child roles that require children provide emotional caretaking to their parents (for discussions, see Chase, 1999; Jurkovic, 1997). Consequently, although excessive involvement in all forms of caretaking may affect the well-being of children, role reversal that requires children to care for an adult as a parent, spouse, or peer may create more problems than expectations that children help with household chores or the care of younger children.

Psychosocial Consequences of Parentification

Over the years, clinicians and researchers have consistently argued that excessive involvement in caretaking contributes to poor developmental outcomes (for discussions, see Chase, 1999; Jurkovic, 1997). Surprisingly, despite the belief that such involvement contributes to compromise of psychosocial adjustment, relatively little is known about the emotional and behavioral correlates of caretaking burden as it unfolds during childhood and adolescence (Earley & Cushway, 2002). At this time, much of the research exploring the potential consequences of parentification has focused on documenting the psychosocial correlates of retrospective reports of caretaking burden during childhood when provided by adults, particularly young adults attending college (e.g., see Fullinwider-Bush & Jacobvitz, 1993; Jacobvitz & Bush, 1996; Mayseless et al., 2004). However, the work that has been conducted with children suggests that excessive involvement in caretaking may contribute to emotional, behavioral, and social problems during childhood and adolescence.

For example, Koerner and her colleagues (Koerner et al., 2004; Lehman & Koerner, 2002) showed that, in the context of divorce, teens cast in the role of parental confidante demonstrated more emotional distress than teens who were not put in that position, and Godsall et al. (2004) showed that, among children affected by parental alcoholism, parentification characterized by involvement in instrumental and emotional caretaking correlated negatively with a concurrent measures of positive self-concept. Most recently, Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac, and Weisshaar (2005) found that, within a sample of middle-school students affected by the war in Bosnia, both degree of caregiving and perceived fairness of caregiving correlated in potentially meaningful ways with concurrent measures of self-efficacy, emotional distress, and academic performance. Furthermore, in a study of school-age children affected by divorce, Johnston (1990) showed that parentification characterized by reversal of emotional and instrumental roles was associated prospectively with somatic symptoms and disturbance in interpersonal relations. Stein et al. (1999) also found that, in a prospective study of teens living with an HIV-seropositive parent, responsibility for household chores correlated positively with internalizing pathology while responsibility to care for a parent correlated positively with externalizing behavior, sexual activity, and substance use.

This Study

Given the empirical literature on the concept, this study was designed to examine the psychosocial correlates of caretaking burden within a sample of 8- to 17-year-old children living in high-risk family systems characterized by urban poverty, maternal substance abuse, and maternal psychopathology. The primary goal was to extend the existing literature by identifying defining characteristics and potential consequences associated with three dimensions of caretaking burden in children: (a) responsibility to care for mother, (b) responsibility for household chores, and (c) responsibility to care for siblings. Three specific hypotheses were targeted for investigation.

First, caretaking burden was expected to be best characterized as a multidimensional, multidetermined construct defined in an additive manner by an array of potential influences broadly organized into three clusters representing (a) the characteristics of the child, (b) the characteristics of the mother, and (c) the characteristics of the family. Given the clinical and empirical literatures on the nature of parentification, age, gender, status as the oldest child living in the home, and status as the only child living in the home were selected to represent important characteristics of the child. Age, ethnic heritage, vocational–educational status, substance abuse, psychiatric distress, personality disturbance, and perception of social support were selected to represent important characteristics of the mother, and single-parent family structure and number of minor children living in the home were selected to represent important characteristics of the family system.

Second, variability in the defining characteristics of different dimensions of caretaking burden was expected. In the context of urban poverty, responsibility to care for mother was expected to be associated with substance abuse, psychiatric distress, and personality disturbance in the mother. However, responsibility for household chores and responsibility to care for siblings were expected to be associated with characteristics of the child, vocational–educational status of the mother, and family structure in a manner reflecting practical demands on children given the socioeconomic status of the family.

Finally, the different dimensions of caretaking burden were expected to correlate with markers of psychopathology and social competence in a curvilinear manner. That is, moderate involvement in caretaking representing developmentally appropriate participation in family life was expected to be associated with less internalizing pathology, less externalizing pathology, better parent–child relations, better peer relations, and more involvement in social and recreational activity. Conversely, both relatively high and relatively low involvement in caretaking were expected to be associated with more internalizing pathology, more externalizing pathology, poorer parent–child relations, poorer peer relations, and less involvement in social and recreational activity. Given the work of Stein et al. (1999), responsibility to care for mother, more so than responsibility for household chores or the care of siblings, was expected to correlate consistently with emotional–behavioral status.

Method

Sample

The sample for this study comprised 361 mother–child dyads recruited into a study examining the psychosocial adjustment of children living in the inner city with a drug-abusing mother (Luthar & Sexton, 2007). For this study, clusters of parents recruited to represent (a) mothers with drug abuse problems, (b) mothers with psychiatric problems, and (c) mothers without substance abuse or psychiatric problems were collapsed into a single group with proper coding of their substance abuse and psychopathology. After three mother-child dyads were excluded because of missing data and two others were excluded because the child was not living in the same household as the mother, the final sample included 356 children 8 to 17 years of age living in urban poverty with their biological mother.

Characteristics of this final sample are outlined in Table 1. As indicated, this was an ethnically diverse sample of middle-aged mothers. On average, the mothers had a high school education, and a majority of them were not working outside the home. Most were living with two or three minor children, often as a single parent. Approximately half of the mothers had a substance abuse problem. Psychiatric distress and personality disturbance were also relatively common, and 41% of the mothers were receiving treatment for a mental health or substance abuse problem. A majority of the mothers with a substance abuse problem were opioid-dependent women enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables of Primary Interest

| Construct and variable | Descriptive statistics | Possible values |

|---|---|---|

| Caretaking burden | ||

| Care for mother | 18.94 (4.77) | 0–32 |

| Household chores | 22.95 (5.66) | 0–40 |

| Care for siblings | 16.26 (4.93) | 0–28 |

| Characteristics of the child | ||

| Age | 12.09 (2.80) | 8–17 |

| Gender (male) | 46% (163) | Yes/no? |

| Oldest child | 36% (129) | Yes/no? |

| Only child | 26% (93) | Yes/no? |

| Characteristics of the mother | ||

| Age | 38.23 (6.20) | 23–55 |

| African American | 52% (184) | Yes/no? |

| Hispanic | 6% (23) | Yes/no? |

| Years of education | 12.45 (2.66) | 0–22 |

| Employed outside home | 39% (138) | Yes/no? |

| Substance abuse problem | 53% (188) | Yes/no? |

| Anxiety symptoms | 15% (52) | Yes/no? |

| Depressive symptoms | 9% (34) | Yes/no? |

| Eccentric personality | 16% (56) | Yes/no? |

| Dramatic personality | 32% (115) | Yes/no? |

| Anxious personality | 22% (79) | Yes/no? |

| Social support: Family | 12.49 (4.20) | 0–20 |

| Social support: Friends | 12.90 (3.04) | 0–20 |

| Characteristics of the Family | ||

| Single-parent family | 45% (162) | Yes/no? |

| No. of minor children | 2.55 (1.45) | 1–8 |

| Potential consequences: Child report | ||

| Psychological distress | 43.77 (8.25) | 33–90 |

| School maladjustment | 47.09 (8.63) | 29–88 |

| Parent–child relations | 51.99 (7.56) | 10–57 |

| Peer relations | 52.82 (7.61) | 10–58 |

| Potential consequences: Maternal report | ||

| Internalizing pathology | 48.88 (12.30) | 27–120 |

| Externalizing pathology | 51.19 (14.69) | 27–120 |

| Social competence | 47.80 (11.17) | 19–78 |

Note. Descriptive statistics represent the mean for continuous variable with the standard deviation in parentheses and the percent for categorical variables with the count in parentheses. All categorical variables were dummy coded so that Yes = 1 and no = 0.

As noted in Table 1, the children were, on average, approximately 12 years of age, there was approximately equal representation of boys and girls, and many of the children were characterized as either the oldest or the only child living in the home. Food stamps (62%), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits (50%), rental subsidy (40%), and income from legal employment (39%) were the most common sources of financial support for the family, and the median family income from all sources was approximately $1,699 per month. All of the participants were living in southern New England.

Measures

Caretaking Burden

The Child Caretaking Scale (Baker & Tebes, 1994) was used to measure caretaking burden from the perspective of the children. The Child Caretaking Scale is a self-report inventory originally designed for use in a study of children living with a mother experiencing psychiatric difficulty (Baker, 1997). For this study, children rated their degree of agreement with statements reflecting involvement in different form of caretaking activity along a 5-point scale that ranged from strongly disagree (0) to neutral (2) to strongly agree (4). Twenty-five items from the scale were used to define three dimensions of caretaking burden: (a) responsibility to care for mother (“My mother needs me to be her friend”), (b) responsibility for household chores (“It is my job to make sure the door is locked before I go to bed”), and (c) responsibility to care for siblings (“I help my brothers and sisters get ready for school every morning”). In this sample, coefficients alpha were .63 for the Responsibility to Care for Mother scale, .61 for the Responsibility for Household Chores scale, and .75 for the Responsibility to Care for Siblings scale.

Defining Characteristics of Caretaking Burden

Characteristics of the child

Information provided by mothers was used to define four characteristics of the child hypothesized to be defining characteristics of caretaking burden: (a) age of the child, (b) gender of the child, (c) status as the oldest child living in the home, and (d) status as the only child living in the home.

Characteristics of the mother

Information obtained from mothers during administration of several structured interviews and a battery of self-report instruments was used to define 13 variables representing seven constructs thought to be defining characteristics of caretaking burden: (a) age, (b) ethnicity, (c) vocational–educational status, (d) substance abuse, (e) psychiatric distress, (f) personality disturbance, and (g) perception of social support. Ethnic heritage was dummy coded to represent mothers of African American heritage versus all others and mothers of Hispanic heritage versus all others. Similarly, information derived from a structured interview was used to define two vocational– educational characteristics: (a) years of formal education completed and (b) employment outside the home.

The Clinical Syndrome and Clinical Personality Pattern scales from the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory III (Millon, Davis, & Millon, 1997) were used to document the presence of psychiatric distress and personality disturbance in the mothers. For this study, base rate scores greater than 74 on the Dysthymia or Major Depression scales were used to document the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms, and base rate scores greater than 74 on the Anxiety or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder scales were used to define clinically significant anxiety symptoms. Similarly, base rate scores greater than 74 were used to code the presence of clinically significant disturbance in personality characterized by an Odd–Eccentric (Cluster A) pattern derived from the Paranoid, Schizoid, and Schizotypal scales, a Dramatic–Erratic (Cluster B) pattern derived from the Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, and Narcissistic scales, and an Anxious–Fearful (Cluster C) pattern derived from the Avoidant, Dependent, and Obsessive–Compulsive scales.

In addition, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM–IV (Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, 1995) was used to document the presence of a current substance use disorder involving (a) alcohol, (b) opioids, (c) cocaine, (d) marijuana, (e) sedatives/hypnotics, (f) amphetamines, or (g) hallucinogens. Finally, the Perceived Social Support Scale developed by Procidano (1992) was used to document perception of social support available to the mother from family and friends. In this sample, coefficients alpha were .78 for the Family subscale and .60 for the Friends subscale.

Characteristics of the family

Information provided by mothers was also used to define two structural characteristics of the family hypothesized to be defining characteristics of caretaking burden: (a) single-parent family and (b) number of minor children living in the home.

Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden

Selected scales from the Behavioral Assessment System for Children (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992) were used to document both emotional–behavioral disturbance and social competence in the children. The Self-Report of Personality was completed by the children, and the Parent Rating Scales were completed by the mothers. Depending on the age of the child, the Child or Adolescent version of the instruments was used with each mother–child dyad.

The initial development, psychometric properties, and normative data for the scales have been described by Reynolds and Kamphaus (1992). For this study, normative data were used to transform raw scores to T scores reflecting quality of psychosocial adjustment when compared with a nationally representative sample of children the same age. For measures of emotional–behavioral disturbance, T scores that fall between 60 and 69 identify children with mild to moderate psychopathology, and T scores greater than 70 identify children with serious psychopathology. Similarly, for the measures of social competence, T scores that fall between 40 and 31 identify children with mild to moderate compromise of social competence, and T scores less than 31 identify children with serious compromise of social competence.

Potential consequences reported by children

The Clinical Maladjustment and School Maladjustment composites from the Self-Report of Personality were used to document emotional distress and alienation from school when examined from the perspective of the children. The Clinical Maladjustment composite documents internalizing pathology characterized by anxiety, a negative attributional style, and feelings of tension, pressure, and inability to cope. The School Maladjustment composite documents negative attitudes toward school, teachers, and learning. Higher scores on both composites reflect more psychopathology.

Similarly, the Relations With Parents and Interpersonal Relations scales from the Self-Report of Personality were used to document social competence from the perspective of the children. The Relations With Parents scale documents quality of parent–child relationships and perception of the family environment. The Interpersonal Relations scale documents quality of peer relationships. Higher scores on both composites represent more social competence.

Potential consequences reported by mothers

The Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems composites from the Parent Rating Scales were used to document emotional–behavioral disturbance in the children when examined from the perspective of the mothers. The Internalizing Problems composite documents internalizing pathology characterized by anxiety, depressive, and somatic symptoms. The Externalizing Problems composite documents externalizing pathology characterized by hyperactive, aggressive, disruptive, antisocial behaviors. Higher scores on both these composites represent more psychopathology.

The Leadership scale from the Parent Rating Scales was used to document social competence in the children when examined from the perspective of the mothers. The Leadership scale documents positive adaptation to school, social problem-solving skills, and positive involvement in social and recreational activity. Higher scores on this scale represent more social competence.

Procedure

We recruited mother–child dyads using targeted announcements posted in supermarkets, social service offices, primary care clinics, drug abuse treatment programs, mental health clinics, and other places frequently visited by women living in urban poverty. When a mother expressed interest in participating, both mother and child were screened to document eligibility for participation. If they were considered eligible, informed consent was obtained in writing from the mother for her participation, and informed consent for participation of the child was obtained in writing from a legal guardian, typically the biological mother enrolling with the child. Informed assent was also obtained in writing from each child.

All research assessments were completed during a single session divided into two 60- to 90-min segments, and each assessment was completed by a research assistant with at least a bachelor degree in psychology or social work. Most of the time, mother and child completed the study on the same day. Mothers and children who completed a research assessment each received $40 compensation for their time, and mothers received an additional $20 if the family completed the study. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board for the Yale University School of Medicine.

Data Analyses

Defining Characteristics of Caretaking Burden

After the conceptual and empirical literatures were used to identify potential correlates of parentification, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses to identify the most salient defining characteristics for each dimension of caretaking burden. In each statistical analysis, the 19 variables representing the defining characteristics were entered into a standard multiple regression analysis as the independent variables. The three dimensions of caretaking burden were examined separately as the dependent variables. In the absence of any conceptual rationale to guide ordering of the variables for sequential entry, backward elimination was used to reduce the full set of 19 independent variables to a subset of salient defining characteristics for each of the three dimensions. Variables producing parameter estimates with p values less than .10 were allowed to remain in the final model as potentially meaningful defining characteristics of caretaking burden.

Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden

In a second set of statistical analyses, we used hierarchical multiple regression to examine the potential consequences of caretaking burden for the children. In each statistical analysis, the independent variables were entered sequentially on four steps. On the first step, age and gender of the child were entered as covariates to allow for age and gender differences in compromise of psychosocial adjustment relative to a normative sample of children the same age. On the second step, the three dimensions of caretaking burden were entered to test for linear relationships with specific markers of psychosocial adjustment. On the third step, product terms representing two-way interaction of the different dimensions of caretaking burden were entered to test for moderation of linear relationships with specific markers of psychosocial adjustment by another dimension of caretaking burden. This was also done because Ganzach (1997) has shown that, if the appropriate product terms are not included in the regression equation, the statistical analysis may fail to detect a true curvilinear relationship when one exists or it may invert the true nature of the relationship. On the final step, quadratic terms for each dimension of caretaking burden were entered to test for curvilinear relationships with specific markers of psychosocial adjustment. As suggested by Aiken and West (1991), product and quadratic terms were created with the measures of caretaking burden centered.

In this series of statistical analyses, the seven markers of psychosocial adjustment as reported by the children and their mothers served as the dependent variables. We examined each marker of psychosocial adjustment separately to preserve the integrity of the constructs and clinical thresholds defined by Reynolds and Kamphaus (1992). Within each statistical analysis, R2 and change in R2 were computed for each block of independent variables.

Because they did not represent tests of specific hypotheses, only linear terms producing parameter estimates with p values less than .05 after the omnibus test for the block were considered statistically significant, potentially meaningful linear effects. Similarly, because interaction and quadratic effects can be difficult to detect (McClelland & Judd, 1993), product terms producing parameter estimates with p values less than .10 after a significant omnibus test for the block were considered statistically significant, potentially meaningful interaction effects. Finally, because they represented tests of specific hypotheses, quadratic terms producing parameter estimates with p values less than .10 independent of the omnibus test were considered statistically significant, potentially meaningful curvilinear effects (Bedeian & Mossholder, 1994).

When statistically significant quadratic terms emerged, intercepts and unstandardized regression coefficients derived from a simultaneous multiple regression analysis were used to graph the nature of the curvilinear relationship (Ganzach, 1997). Across statistical analyses, there was interest in the consistency of hypothesized relationships. Statistically significant, but inconsistent, findings that may have represented Type I error were not interpreted.

Results

Patterns of Caretaking Burden

As noted in Table 1, the children in this sample confirmed, on average, moderate levels of all types of caretaking with variability across individuals that approximated a normal distribution. Correlation coefficients listed in Table 2 indicate that there was also a positive, moderate correlation among the three dimensions of caretaking, suggesting that they represent conceptually distinct, but related, dimensions of a single construct. As expected, zero-order correlation of the 19 defining characteristics of caretaking burden was generally low to moderate (M = 0.11, SD = 0.14, Mdn = .07), and there was no evidence of singularity or multicollinearity. Although self-report of psychological distress was somewhat lower than the norm, psychosocial adjustment within the sample otherwise compared with that of a nationally representative sample of children the same age (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). Zero-order correlation of the seven markers of psychosocial adjustment was also consistently low to moderate (M = 0.24, SD = 0.17, Mdn = .19), and there was again no evidence of singularity or multicollinearity.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlation Matrix for Variables of Primary Interest

| Construct and variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caretaking burden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Care for mother | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Household chores | .45*** | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Care for siblings | .38*** | .43*** | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Characteristics of the child | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Age | –.08 | .12** | –.06 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Gender (male) | –.14*** | .11** | –.04 | –.07 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Oldest child | .02 | .12** | .27*** | .13** | –.06 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Only child | .12** | –.03 | –.20*** | .01 | –.08 | –.44*** | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Characteristics of the mother | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Age | –.10* | –.09* | –.20*** | .35*** | –.02 | –.24*** | .16*** | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. African American | .08* | .20*** | .10* | .03 | .02 | .07 | –.19*** | –.21*** | — | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Hispanic | .00 | .02 | .04 | –.02 | –.01 | .09 | –.05 | –.07 | –.27*** | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Years of education | –.18*** | –.12** | –.12** | –.04 | .02 | –.16*** | .10* | .27*** | –.04 | –.23*** | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Employed outside home | –.03 | –.05 | .12** | –.02 | .05 | –.07 | –.01 | –.00 | .05 | –.14*** | .29*** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 13. Substance abuse problem | .09 | .06 | .03 | –.07 | .07 | –.08 | .10* | .05 | –.11** | –.00 | –.15*** | –.15*** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 14. Anxiety symptoms | .02 | .04 | .10*** | .04 | .03 | .00 | .04 | –.08 | –.00 | .08 | –.16*** | –.05 | .18*** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 15. Depressive symptoms | –.00 | .04 | .04 | .09* | .05 | .05 | .05 | .00 | –.11** | .15*** | –.19*** | –.18*** | .17*** | .60*** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 16. Eccentric personality | .10* | .08 | .07 | .08 | .00 | .04 | –.01 | –.08 | .05 | .11** | –.22*** | –.15*** | .16*** | .72*** | .62*** | — | |||||||||||||

| 17. Dramatic personality | –.06 | .04 | .04 | .09* | .02 | .02 | –.07 | .03 | –.04 | –.01 | .04 | .07 | –.01 | .41*** | .33*** | .43*** | — | ||||||||||||

| 18. Anxious personality | .07 | .06 | .02 | .08 | .02 | .00 | .01 | .01 | –.15*** | .08 | –.03 | .02 | .04 | .54*** | .49*** | .51*** | .53*** | — | |||||||||||

| 19. Social support: Family | –.12** | –.04 | –.06 | .03 | –.03 | .03 | –.10* | .05 | .18*** | –.04 | .20*** | .02 | –.09* | –.08 | –.17*** | –.07 | –.02 | –.11** | — | ||||||||||

| 20. Social support: Friends | –.14*** | –.09* | –.07 | –.01 | .13** | –.01 | –.07 | .06 | .02 | .06 | .19*** | .03 | –.13** | –.03 | –.11** | –.05 | .00 | –.07 | .39*** | — | |||||||||

| Characteristics of the family | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Single-parent family | .16*** | .20*** | –.01 | .04 | .10* | –.02 | –.02 | –.00 | .18*** | .03 | –.16*** | –.11** | .04 | –.04 | .03 | –.01 | –.07 | –.07 | –.09* | –.03 | — | ||||||||

| 22. No. of minor children | –.16 | .07 | .14*** | .07 | .02 | .49*** | –.64*** | –.12** | .15*** | .03 | –.16*** | –.11** | –.01 | –.08 | –.05 | –.02 | –.05 | –.08 | .11** | .04 | .00 | — | |||||||

| Potential consequences: Child report | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23. Psychological distress | .14*** | .06 | .03 | .13** | .03 | .02 | –.02 | –.03 | .07 | .07 | –.09* | .07 | –.06 | .09* | –.01 | .12** | .01 | .04 | –.08 | .05 | .04 | –.05 | — | ||||||

| 24. School maladjustment | –.04 | –.03 | –.04 | .09* | .19*** | –.03 | –.01 | .05 | –.03 | .03 | –.03 | .07 | .01 | .09* | .06 | .07 | .03 | .06 | –.06 | .06 | .03 | –.04 | .56*** | — | |||||

| 25. Parent–Child relations | .09* | –.03 | .04 | –.12** | –.02 | –.07 | .17*** | –.01 | –.15*** | .02 | .08 | .02 | –.10* | –.04 | –.02 | –.06 | –.07 | –.02 | .01 | –.03 | –.09* | –.12** | –.30*** | –.34*** | — | ||||

| 26. Peer relations | .00 | .04 | .05 | –.08 | –.09* | –.02 | –.02 | –.07 | –.05 | .03 | .09* | –.04 | –.00 | –.03 | .03 | –.02 | .00 | .00 | .07 | –.07 | –.05 | –.01 | –.53*** | –.40*** | .36*** | — | |||

| Potential consequences: Maternal report | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. Internalizing pathology | .05 | –.04 | –.03 | .04 | –.05 | –.05 | .14*** | .04 | .01 | .04 | –.08 | –.04 | .17*** | .26*** | .15*** | .26*** | .04 | .04 | –.04 | .02 | –.01 | –.10* | .22*** | .12** | –.03 | –.17*** | — | ||

| 28. Externalizing pathology | .05 | .03 | .09* | .06 | .13** | .06 | .06 | –.03 | –.01 | .01 | –.14** | –.03 | .22*** | .30*** | .22*** | .27*** | .06 | .05 | –.11** | –.02 | .01 | –.01 | .19*** | .29*** | –.14*** | –.17*** | .66*** | — | |

| 29. Social competence | –.02 | –.04 | –.07 | –.10** | –.07 | –.10** | –.04 | .04 | –.01 | –.01 | .28*** | .13** | –.09* | –.12** | –.11** | –.14*** | –.01 | –.10* | .20*** | .14*** | –.06 | –.01 | –.14*** | –.20*** | .15*** | .12** | –.02 | –.15*** | — |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Defining Characteristics of Caretaking Burden

Responsibility to Care for Mother

As noted in Table 2, there was evidence of positive, relatively modest zero-order correlation between responsibility to care for mother and (a) single-parent family, (b) status as the only child living in the home, and (c) the presence of odd–eccentric personality disturbance in the mother. There was also evidence of negative, relatively limited zero-order correlation with (a) years of education completed by the mother, (b) male gender, (c) perception of social support available to the mother from family, (d) perception of social support available to the mother from friends, and (e) age of the mother. When the 19 defining characteristics were entered into a standard multiple regression, the full model accounted for 15.78% of the variance in this dimension of caretaking burden, F(19, 336) = 3.31, p < .0001.

After backward elimination, nine variables with potentially meaningful relationships remained. These variables are listed in Table 3. In the final multivariate model, responsibility to care for mother correlated positively with (a) single-parent family, (b) status as the only child living in the home, (c) odd–eccentric personality disturbance in the mother, and (d) anxious–fearful personality disturbance in the mother. This dimension of caretaking burden also correlated negatively with (a) age of the child, (b) male gender, (c) years of education completed by the mother, (d) the presence of depressive symptoms in the mother, and (e) the presence of dramatic–erratic personality disturbance in the mother. Together, these nine variables accounted for 12.89% of the variance in responsibility to care for the mother, F(9, 346) = 5.69, p < .001.

Table 3.

Defining Characteristics of Caretaking Burden

| Construct and variable | β | sr 2 | r 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsibility to care for mother | |||

| Characteristics of the child | .048*** | .040*** | |

| Age | –0.11 | .011** | .007 |

| Gender (male) | –0.15 | .021*** | .020*** |

| Only child | 0.12 | .014** | .013** |

| Characteristics of the mother | .056*** | .061** | |

| Years of education | –0.15 | .020*** | .031*** |

| Depressive symptoms | –0.15 | .013** | .000 |

| Eccentric personality | 0.15 | .011** | .010 |

| Dramatic personality | –0.11 | .009* | .004 |

| Anxious personality | 0.14 | .012** | .004 |

| Characteristics of the family | .025*** | .026*** | |

| Single-parent family | 0.16 | .025*** | .026*** |

| Responsibility for household chores | |||

| Characteristics of the child | .036*** | .042*** | |

| Age | 0.11 | .011** | .016** |

| Gender (male) | 0.11 | .013** | .011** |

| Oldest child | 0.11 | .011** | .016** |

| Characteristics of the mother | .034*** | .049*** | |

| African American | 0.16 | .024*** | .040*** |

| Social support: friends | –0.10 | .010** | .008* |

| Characteristics of the family | .023*** | .041*** | |

| Single-parent family | 0.15 | .023*** | .041*** |

| Responsibility to care for siblings | |||

| Characteristics of the child | .077*** | .080*** | |

| Age | –0.10 | .010** | .003 |

| Oldest child | 0.28 | .073** | .072*** |

| Characteristics of the mother | .043*** | .046*** | |

| Years of education | –0.11 | .011** | .014** |

| Employed outside home | 0.16 | .027*** | .013** |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.10 | .009* | .011** |

Note. β = the standardized regression coefficient; sr2 = the squared semipartial correlation coefficient from the final multiple regression analysis; r2 = the square of the zero-order correlation coefficient for each variable and the multiple r2 for each block of variables.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Alone, each of these nine variables accounted for 1% to 2.5% of the variance in this dimension of caretaking burden, and as noted in Table 3, there was evidence of suppressor effects involving several of the variables. That is, when examined in combination with other defining characteristics, the explanatory power of several variables was enhanced significantly when compared with their explanatory power when considered alone (for a discussion, see Paulhus, Robins, Trzesniewski, & Tracy, 2004). When the bootstrapping method of assessing the indirect effects of multiple mediators described by Preacher and Hayes (2005) was used to explore the exact nature of these suppressor effects, there were indications that (a) the explanatory power associated with male gender was enhanced significantly primarily through its relationship with single-parent family, (b) the explanatory power associated with depressive symptoms and anxious– fearful personality disturbance were both enhanced significantly primarily through their relationship with one another, and (c) the explanatory power associated with dramatic– erratic personality disturbance was enhanced significantly through its relationship with both odd– eccentric and anxious–fearful personality disturbance.

Responsibility for Household Chores

Zero-order correlation coefficients presented in Table 2 indicate that responsibility for household chores correlated positively and relatively modestly with (a) African American heritage, (b) single-parent family, (c) age of the child, (d) status as the oldest child living in the home, and (e) male gender. The zero-order correlation coefficients also indicate that this dimension of caretaking burden correlated negatively and relatively modestly with (a) years of education completed by the mother, (b) perception of social support available to the mother from friends, and (c) maternal age. When the 19 defining characteristics were entered into a standard multiple regression, the full model accounted for 13.84% of the variance in this dimension of caretaking burden, F(19, 336) = 2.84, p < .0001.

After backward elimination, six variables with potentially meaningful relationships remained. These variables are also listed in Table 3. In this final multivariate model, responsibility for household chores correlated positively with (a) age of the child, (b) male gender, (c) status as the oldest child living in the home, (d) African American heritage, and (e) single-parent family. This dimension of caretaking burden also correlated negatively with perception of social support available to mother from friends. Together, the six variables accounted for 11.19% of the variance in responsibility for household chores, F(6, 349) = 7.33, p < .0001. Alone, each accounted for 1% to 2.4% of the variance, and there was evidence that the explanatory power associated with perception of social support available from friends was enhanced significantly through its relationship with African American heritage.

Responsibility to Care for Siblings

Finally, as indicated in Table 2, there was evidence of positive, relatively limited zero-order correlation between responsibility to care for siblings and (a) status as the oldest child living in the home, (b) number of minor children living in the home, (c) maternal employment outside the home, (d) the presence of anxiety symptoms in the mother, and (e) African American heritage. There was also evidence of negative, relatively modest zero-order correlation with (a) status as the only child living in the home, (b) age of the mother, and (c) years of education completed by the mother. When the 19 defining characteristics were entered into a standard multiple regression, the full model accounted for 14.75% of the variance in this dimension of caretaking burden, F(19, 336) = 3.06, p < .0001.

After backward elimination, five variables with potentially meaningful relationships remained. Again, these variables are listed in Table 3. In this final multivariate model, responsibility for the care of siblings correlated positively with (a) status as the oldest child living in the home, (b) maternal employment outside the home, and (c) the presence of anxiety symptoms in the mother. This dimension of caretaking burden also correlated negatively with (a) age of the child and (b) years of education completed by the mother. Together, the five correlates accounted for 12.31% of the variance in responsibility for the care of siblings, F(5, 350) = 9.83, p < .0001. Alone, each accounted for 1% to 7.5% of the variance, and there were indications that (a) the explanatory power associated with age of the child was enhanced significantly through its relationship with status as the oldest child in the home and (b) the explanatory power associated with employment outside the home was enhanced significantly through its relationship with years of education completed by the mother.

Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden

Child Report

Results of hierarchical multiple regression analyses examining relationships involving caretaking burden and the psychosocial adjustment of children when examined from their perspective are summarized in Table 4. As indicated, there were statistically significant relationships involving both covariates and negative attitudes toward school such that, relative to other children the same age, boys and older children reported more negative attitudes. The block of variables containing the quadratic terms also proved statistically significant for three of the four dimensions of psychosocial adjustment, and there was consistent evidence of unique, statistically significant quadratic relationships involving responsibility to care for mother and (a) psychological distress, (b) negative attitudes toward school, and (c) positive relations with parents. There was also a statistically significant quadratic relationship between responsibility for household chores and negative attitudes toward school. There were no statistically significant linear relationships, and although the block containing the product terms proved statistically significant for the two markers of social competence, there were no unique statistically significant moderator effects.

Table 4.

Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden: Child Report

| Psychological distress |

School maladjustment |

Parental relations |

Peer relations |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step and block | R 2 | Δ R 2 | R 2 | Δ R 2 | R 2 | Δ R 2 | R 2 | Δ R 2 |

| 1. Covariates | .019** | .019** | .045*** | .045*** | .015* | .015* | .016* | .016* |

| 2. Linear terms | .047** | .028** | .050*** | .005 | .024 | .009 | .024 | .008 |

| 3. Interactive terms | .048** | .001 | .053** | .003 | .102** | .078*** | .066*** | .042*** |

| 4. Quadratic terms | .068* | .020* | .096*** | .044*** | .142*** | .040*** | .072*** | .006 |

| Variable | B | SE | sr 2 | B | SE | sr 2 | B | SE | sr 2 | B | SE | sr 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.48 | 0.16 | .025*** | 0.37 | 0.16 | .014** | –0.26 | 0.14 | .009 | –0.30 | 0.15 | .011** |

| Gender (male) | 1.21 | 0.90 | .005 | 3.62 | 0.93 | .040*** | –0.57 | 0.79 | .001 | –2.09 | 0.83 | .017** |

| Care for the mother | 0.36 | 0.11 | .030*** | 0.09 | 0.11 | .001 | 0.07 | 0.10 | .001 | –0.13 | 0.10 | .005 |

| Household chores | –0.07 | 0.10 | .001 | –0.10 | 0.10 | .002 | 0.01 | 0.08 | .000 | 0.21 | 0.09 | .015** |

| Care for siblings | 0.00 | 0.10 | .000 | 0.01 | 0.10 | .000 | –0.04 | 0.09 | .000 | –0.00 | 0.09 | .000 |

| Mother × Household Chores | –0.04 | 0.02 | .007 | –0.07 | 0.02 | .025*** | –0.00 | 0.02 | .000 | –0.04 | 0.02 | .010* |

| Mother × Siblings | –0.01 | 0.02 | .001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .001 | –0.03 | 0.02 | .005 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .000 |

| Household Chores × Siblings | –0.00 | 0.02 | .000 | –0.00 | 0.02 | .000 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .000 | –0.00 | 0.02 | .000 |

| Care for the mother2 | 0.05 | 0.02 | .018*** | 0.05 | 0.02 | .024*** | –0.06 | 0.01 | .038*** | –0.02 | 0.02 | .004 |

| Household chores2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .002 | 0.03 | 0.01 | .018*** | 0.00 | 0.01 | .000 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .001 |

| Care for siblings2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .000 | –0.02 | 0.02 | .003 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .000 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .000 |

| Intercept | 42.92 | 0.63 | 46.00 | 0.65 | 53.26 | 0.55 | 53.35 | 0.58 |

Note. B = the unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = the standard error of the unstandardized regression coefficient; sr2 = the squared semipartial correlation coefficient from the hierarchical multiple regression analysis.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

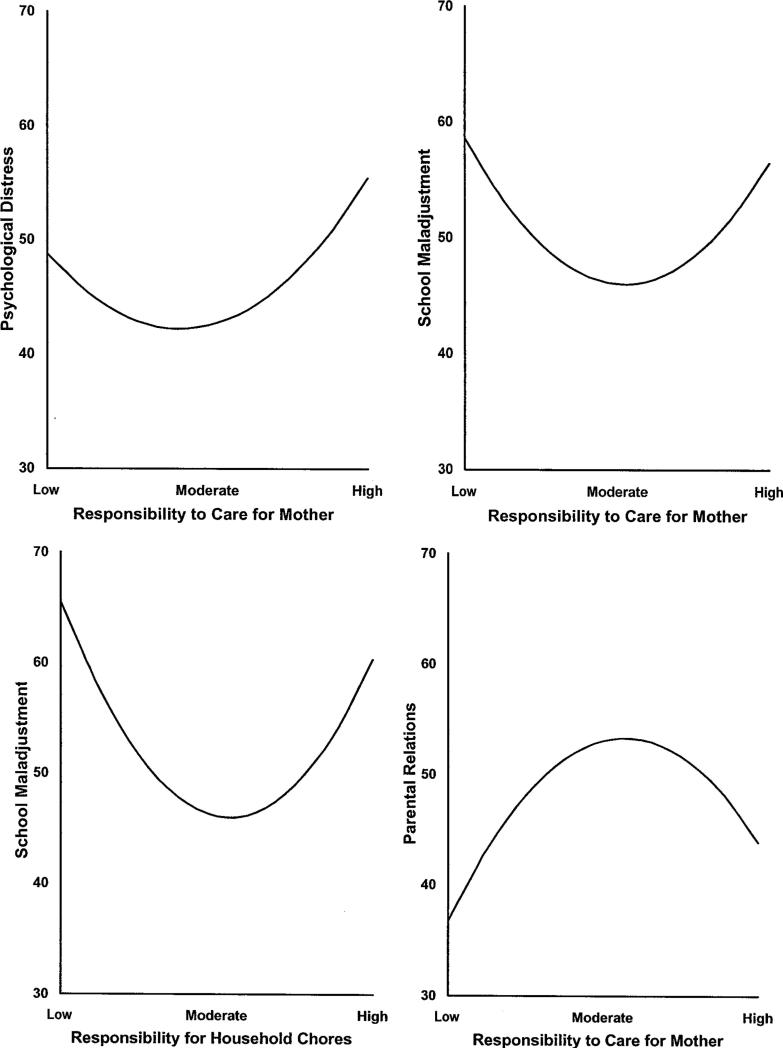

The nature of the statistically significant curvilinear relationships is illustrated in Figure 1. As expected, moderate involvement in emotional caretaking of the mother was associated with less psychological distress, less negative attitudes toward school, and better parent– child relations. Moderate involvement in household chores was also associated with less negative attitudes toward school. Although associated with relatively poorer psychosocial adjustment, neither extremely high nor extremely low levels of responsibility to care for mother were associated with clinically significant psychological distress or alienation from school. However, extremely high and extremely low levels of responsibility to care for mother were associated with clinically significant compromise of parent– child relations, and extremely high and extremely low responsibility for household chores were associated with clinically significant alienation from school.

Figure 1.

Curvilinear relationships involving caretaking burden and child report of psychopathology and social competence. Values for the measures of psychopathology and social competence represent T scores derived from normative data reported by Reynolds and Kamphaus (1992).

Maternal Report

Results of hierarchical multiple regression analyses examining relationships involving caretaking burden and the psychosocial adjustment of children when examined from the perspective of their mothers are summarized in Table 5. As indicated, there were statistically significant relationships involving the covariates and both externalizing pathology and social competence. Relative to other children the same age, boys and older children were described as having more behavioral difficulty, and older children were described as being less involved in social and recreational activity in the community. As expected, there were unique, statistically significant quadratic relationships involving responsibility to care for mother and both internalizing and externalizing pathology, but again there were no statistically significant linear relationships and no statistically significant moderator effects.

Table 5.

Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden: Maternal Report

| Internalizing pathology |

Externalizing pathology |

Social competence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step and block | R 2 | Δ R 2 | R 2 | Δ R 2 | R 2 | Δ R 2 |

| 1. Covariates | .004 | .004 | .023** | .023** | .018** | .018** |

| 2. Linear effects | .012 | .008 | .039** | .016 | .026 | .008 |

| 3. Interactive effects | .032 | .021* | .042* | .003 | .036 | .010 |

| 4. Quadratic effects | .047 | .015 | .054* | .012 | .042 | .006 |

| Variable | B | SE | sr 2 | B | SE | sr 2 | B | SE | sr 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.26 | 0.24 | .003 | 0.50 | 0.16 | .008* | –0.50 | 0.14 | .015** |

| Gender (male) | –0.90 | 1.36 | .001 | 4.85 | 0.93 | .025*** | –2.00 | 0.79 | .007 |

| Care for the mother | 0.28 | 0.17 | .008 | 0.28 | 0.11 | .005 | –0.00 | 0.10 | .000 |

| Household chores | –0.13 | 0.15 | .002 | –0.23 | 0.10 | .005 | 0.04 | 0.08 | .000 |

| Care for siblings | –0.07 | 0.15 | .000 | 0.38 | 0.10 | .012 | –0.22 | 0.09 | .007 |

| Mother × Household Chores | –0.03 | 0.03 | .002 | –0.01 | 0.02 | .003 | –0.01 | 0.02 | .000 |

| Mother × Siblings | –0.05 | 0.03 | .006 | –0.04 | 0.02 | .001 | –0.01 | 0.02 | .000 |

| Household Chores × Siblings | –0.00 | 0.03 | .000 | –0.02 | 0.02 | .009 | 0.04 | 0.02 | .007 |

| Care for mother2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | .010* | 0.06 | 0.02 | .009* | –0.00 | 0.01 | .000 |

| Household chores2 | –0.02 | 0.02 | .004 | –0.01 | 0.01 | .000 | –0.02 | 0.01 | .005 |

| Care for siblings2 | –0.01 | 0.02 | .000 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .001 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .001 |

| Intercept | 49.51 | 0.95 | 50.53 | 1.13 | 53.26 | 0.55 |

Note. B = the unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = the standard error of the unstandardized regression coefficient; sr2 = the squared semipartial correlation coefficient from the hierarchical multiple regression analysis.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

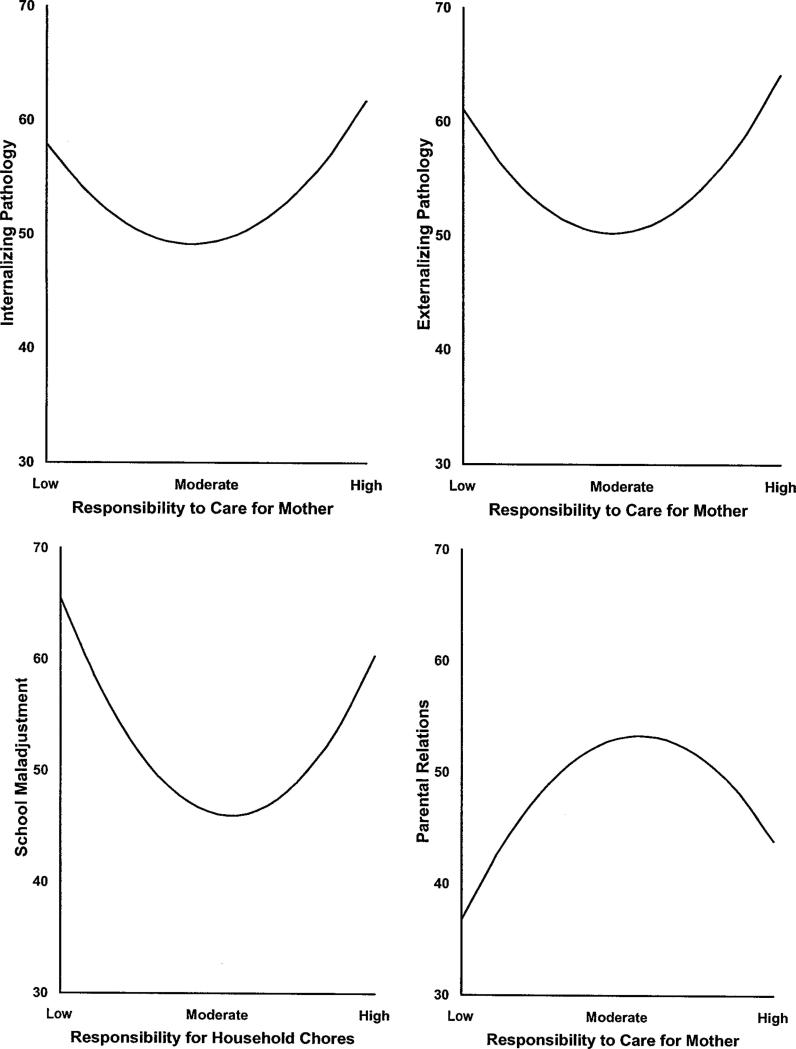

The nature of the statistically significant curvilinear relationships are illustrated in Figure 2. As expected, moderate involvement in emotional caretaking was associated with less internalizing and less externalizing pathology. Although the relationships were not as robust as those noted for child report of psychosocial adjustment, extremely high levels of responsibility to care for mother were clearly associated with mild to moderate psychopathology. Moreover, extremely low levels of responsibility to care for the mother were also associated with mild to moderate externalizing pathology.

Figure 2.

Curvilinear relationships involving caretaking burden and maternal report of psychopathology. Values for the measures of psychopathology represent T scores derived from normative data reported by Reynolds and Kamphaus (1992).

Discussion

Patterns of Caretaking Burden

Consistent with the conceptual model of parentification outlined by Jurkovic and his colleagues (2004), the results of this investigation suggest that the phenomena should be defined as a multidimensional, multidetermined process that may vary with social circumstance. Building upon distinctions involving type versus object of caretaking outlined by Jurkovic (1997), the results of this study provide empirical support for conceptual distinctions involving (a) emotional caretaking of a parent, (b) instrumental activity within the home, and (c) instrumental caretaking of siblings. Consistent with the idea that parentification represents distortion of normative family process, moderate levels of involvement in all three forms of caretaking appeared to be the norm in this social context. Moreover, although extensive involvement in caretaking occurred relatively infrequently, so did minimal involvement, suggesting that, among children living in urban poverty, both under- and overinvolvement in caretaking may represent disturbance in family process.

Defining Characteristics of Caretaking Burden

Given the existing literature, it is noteworthy that the results of this study also highlighted the multidetermined nature of caretaking burden. The three dimensions of caretaking examined in this study correlated differently with constructs repeatedly defined as causal influences in the clinical literature. However, although combinations of specific factors may actually potentiate the influence of one another, the explanatory power of optimal combinations of circumstances was still relatively limited. Surprisingly, although commonly associated with parental substance abuse and parental psychopathology in the clinical literature, maternal substance abuse and maternal psychopathology did not emerge as robust correlates of caretaking burden in either bivariate or multivariate models. Instead, the different dimensions of caretaking burden correlated more consistently with characteristics of the child, vocational–educational status of the mother, and family structure.

Although frequently examined as the consequence of a specific family process such as parental alcoholism, the results of this study suggest that parentification needs to be defined as a complex, multidetermined phenomenon in which parental psychopathology and substance abuse may only play a limited role in family process that contributes to children being inappropriately involved in caretaking activity. Surprisingly, although some forms of psychopathology in mothers correlated positively with caretaking burden in children, others correlated negatively. Specifically, clinically significant anxiety symptoms along with odd–eccentric and anxious–fearful personality disturbance correlated positively with specific dimensions of caretaking burden, whereas clinically significant depressive symptoms and dramatic–erratic personality disturbance correlated negatively with specific dimensions of caretaking burden. As expected, personality disturbance in mothers was more clearly associated with children being responsible to care for their mother.

Furthermore, although Stein et al. (1999) and Godsall et al. (2004) noted positive relationships between parental substance abuse and parentification, maternal substance abuse did not prove to be a significant correlate of caretaking burden in a statistical model that also included representation of psychiatric distress and personality disturbance. This may have occurred because of the comorbid nature of substance abuse, affective distress, and personality disturbance in women. Although many of the mothers confirmed ongoing use of alcohol and illicit drugs, treatment effects may have also minimized the relative contribution of maternal substance abuse because many of the mothers with a substance abuse problem were enrolled in drug abuse treatment. If mothers were actively using outside of treatment, substance abuse may have emerged as a more salient correlate of all three dimensions of caretaking burden.

Taken together, the results of this study raise questions about the ways that dynamic family processes occurring in the context of urban poverty contributes to the parentification of children. The findings suggest that maternal psychopathology, particularly some forms of disturbance in personality, may create the need for emotional caretaking that transcends social circumstance. In contrast, psychosocial stress common among women struggling with single-parent family structures, limited formal education, the need to work outside the home, and a lack of social support may contribute to the need for instrumental assistance defined primarily by social circumstances. Once the need for emotional versus instrumental support has been established, characteristics of the children present within the home may determine which child is actually involved in caretaking. As the process evolves, severity of maternal psychopathology and degree of situational stress may then determine the extent to which a specific child is involved.

Consistent with this, birth order, chronological age, and gender of the child emerged as important defining characteristics of caretaking burden. It is noteworthy that the girls in this sample reported significantly more responsibility to care for mother but less involvement in household chores. Although researchers frequently argue that mothers are more likely to turn to daughters for emotional and instrumental support when distressed (e.g., see Crouter, Head, Bumpus, & McHale, 2001; Koerner et al., 2004), the existing literature is equivocal on gender differences in both emotional and instrumental caregiving during childhood and adolescence. Dolgin (1996) and Hetherington (1999) found that divorced mothers were likely to involve daughters rather than sons in emotional caretaking after divorce, but Jurkovic et al. (2001), Koerner et al. (2004), and Stein et al. (1999) did not find gender differences in reversal of caretaking roles.

Similarly, although some researchers have found that girls report more involvement in household chores within stressed family systems (e.g., see Hetherington, 1999; Stein et al., 1999), girls in North America do not consistently report more responsibility for housework (Larson & Verma, 1999). In general, children tend to be involved in different types of housework on the basis of the gender typing of the task (e.g., see McHale, Bartko, Crouter, & Perry-Jenkins, 1990). Consequently, the boys in this study may have reported more responsibility for household chores because the measure of caretaking burden used in this study included several items that asked about involvement in traditionally male chores such as caring for the yard, fixing things, emptying the garbage, and shopping alone (McHale et al., 1990).

When characteristics of the children were considered, the oldest child living in the home was more likely to be involved in household chores and the care of siblings, whereas an only child was more likely to be involved in the emotional caretaking of mother. Responsibility for household chores also increased with chronological age, whereas responsibility to care for mother and responsibility for household chores declined with chronological age. This pattern of findings is generally consistent with other research indicating that (a) the oldest child is typically more involved in household chores (e.g., see Crouter et al., 2001) and (b) responsibility to care for younger siblings tends to occur most frequently during middle childhood (Zukow-Goldring, 2002). Unfortunately, status within the sibling subsystem has not been examined in other research exploring the nature of parentification. In one of the few investigations to consider birth order, Jurkovic et al. (2001) did not find a relationship between sibling status and either current or past involvement in caregiving, but they did not distinguish children who were an only child from those who were an oldest child. The results of this study suggest that the distinction may be important because each represents differential risk for inappropriate involvement in a specific form of caretaking.

Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden

As expected, responsibility to care for mother was consistently associated with relatively poorer psychosocial adjustment. When examined from the perspective of both the children and their mothers, there was evidence of significant, potentially meaningful curvilinear relationships such that moderate levels of emotional caretaking were associated with less psychological distress, less behavioral difficulty, less alienation from school, and better parent–child relations. Despite the consistency of these curvilinear relationships, it is noteworthy that responsibility to care for the mother was not associated with compromise of peer relations or restriction of social and recreational activity.

Again, the results support the idea that parentification should be conceptualized as a distortion of normative family process that typically supports positive child development through age-appropriate involvement in caretaking within the family. As suggested by Jurkovic (1997; Jurkovic et al., 2004), moderate levels of emotional caretaking were clearly associated with less emotional and less behavioral difficulty. Children reporting moderate involvement in emotional caretaking also reported more positive parent–child relations, whereas children reporting both extensive and limited involvement in emotional caretaking also reported relatively poorer parent–child relations. When examined from the perspective of the children, family systems that conveyed expectations that the children provide some emotional support to their mother were clearly viewed as the most supportive, most validating family environments. In the context of urban poverty, where mothers and children may be relatively isolated in stressful circumstances, expectations that children provide some degree of emotional support to their mother may reflect a degree of family cohesion that is both normative and adaptive for all family members.

Although there was some evidence that extensive and limited responsibility to care for mother were both associated with relatively poorer psychosocial adjustment, it is noteworthy that the effects were small and that emotional caretaking was not consistently associated with either clinically significant psychopathology or serious compromise of social competence. When examined from the perspective of the children, only limited responsibility to care for mother was associated with clinically significant disturbance in parent–child relations. When examined from the perspective of the mothers, extensive and, to a lesser extent, limited responsibility to care for mother were more consistently associated with mild to moderate internalizing and externalizing pathology. Unfortunately, although the clinical literature often focuses on the pathological nature of the process, researchers, for the most part, have not considered the extent to which excessive involvement in emotional caretaking contributes to compromise of psychosocial adjustment that exceeds some clinical threshold. The results of this study suggest that, although excessive involvement in emotional caretaking may contribute, caretaking burden alone may not consistently explain the presence of clinically significant disturbance in emotional, behavioral, and social adaptation.

Given the clinical literature, it is noteworthy that, with only one exception, instrumental caretaking was not associated in any potentially meaningfully way with either psychopathology or social competence. Responsibility for household chores was associated with negative attitudes toward school such that children with moderate responsibility to help at home demonstrated less alienation from school, whereas children with high and low responsibility demonstrated more alienation. Again, this relationship may reflect reasonable expectations that children accept responsibility for both their chores at home and their work at school, whereas children burdened with work at home may find that school only further taxes their resources and children with no responsibility at home may find school overly restrictive and excessively demanding. In general, the finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted by Chase, Deming, and Wells (1998) who found that relatively poorer academic status on admission to college was associated with greater caretaking burden during childhood.

Beyond this isolated finding, there was no evidence that either responsibility for household chores or responsibility to care for siblings was associated with psychopathology or compromise of social competence in this context. Unfortunately, either other researchers have focused on the potential consequences of emotional caretaking alone (e.g., see Johnston, 1990; Koerner et al., 2004; Lehman & Koerner, 2002), or they have not clearly distinguished instrumental from emotional caretaking (e.g., see Godsall et al., 2004; Jurkovic et al., 2005). However, although at odds with the clinical literature, the pattern of findings from this study is generally consistent with that reported by Stein et al. (1999) who found that emotional, rather than instrumental, caretaking was more clearly associated with compromise of psychosocial adjustment. The results of both investigations are also consistent with other research that has found inconsistent, qualified relationships involving responsibility for household chores and the psychosocial adjustment of children (e.g., see Grusec, Goodnow, & Cohen, 1996).

Limitations

Although the results of this study expand understanding of both the defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in urban poverty, there are a number of limitations that deserve mention. First, researchers do not currently agree about how to best conceptualize and measure parentification (Earley & Cushway, 2002; Kerig, 2005), and other approaches to definition and measurement (e.g., see Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Godsall et al., 2004; Macfie et al., 2005) may have produced different results. Consistent with this, the measure of caretaking burden used in this study may not have accurately captured those aspects of caretaking burden that contribute directly to compromise of psychosocial adjustment, particularly the problematic aspects of excessive involvement in household chores and the care of siblings. Moreover, Jurkovic and his colleagues (Jurkovic et al., 2001; Jurkovic et al., 2004) have been arguing that the perception of fairness may be a critical dimension of caretaking burden when examined from the perspective of children, and the results of this study may have been different if a measure that incorporated the concept of perceived fairness had been used.

Next, this study was pursued with children living in a specific social context. Although the results expand understanding of caretaking burden among children living in urban poverty, the findings may not generalize to children living in rural poverty, working-class environments, or suburban affluence. Conceptually, it is important to acknowledge that the nature of caretaking burden may vary with the social context (for a discussion, see Jurkovic et al., 2004). Highlighting the importance of social circumstances, Jurkovic et al. (2004) have outlined ways that excessive caretaking may evolve for children living in economically disadvantaged, Latino family systems where stress associated with immigration may be an important influence. Similarly, Chase (2001), Jurkovic, Morrell, and Casey (2001), and Wells and Miller (2001) have outlined ways in which developmentally inappropriate caretaking may evolve in affluent, suburban family systems in response to the pressure to compete and achieve. Very recently, Peris and Emery (2005) outlined ways that the psychosocial stress associated with the divorce process may provoke parents to inappropriately involve children in a caretaking role.

Finally, although they can highlight relationships that should be explored in longitudinal investigations, statistical models generated from data collected concurrently do not provide information about relationships as they unfold over time, and they cannot be used to clearly establish causality. Consequently, although the existing literature guided selection of the variables used to represent defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden, they may not actually represent causes and consequences. For example, although internalizing pathology and quality of interpersonal relations have consistently been examined as potential consequences of caretaking burden in cross-sectional research designs, emotional distress and poor interpersonal relations may actually be a cause, rather than a consequence, of caretaking as children who are reluctant to leave the home because of emotional distress or poor peer relations focus their attention on caretaking activity within the home.

Conclusions

Directions for Future Research

As researchers seek empirical verification of conceptual definitions, mechanisms of influence, and potential consequences outlined in the clinical literature, they need to think of parentification as a multidimensional, multidetermined phenomenon that represents distortion of normative family process occurring in a social context. Moreover, researchers need to consider the possibility that, when compared with involvement in instrumental caretaking, responsibility to provide emotional caretaking to a parent may reflect greater disturbance in family process with greater risk for emotional–behavioral disturbance in children. Likewise, they need to acknowledge that little to no involvement in caretaking activity may also represent serious disturbance in family process with substantial risk for compromise of positive child development. While acknowledging the potential for negative effects on the psychosocial development of children, researchers must also better document ways that involvement in caretaking contributes to positive developmental outcomes as children move through childhood and adolescence. They also need to consider more seriously the possibility that the relationship between caretaking burden and the psychosocial adjustment of children may be curvilinear in nature. Finally, researchers need to explore the nature of caretaking burden in longitudinal investigations of family process and child development both within and across social contexts to support more definite conclusions about the causes and consequences of caretaking activity as they unfold under different circumstances.

Directions for Clinical Practice

In addition to highlighting a direction for future research, the results of this study offer some direction for clinicians working with children living in urban poverty. First, the results suggest that clinicians should be sensitive to ways that ethnic heritage and economic context may influence expectations children help with caretaking. As suggested by Jurkovic et al. (2004), they must be careful not to identify sociocultural differences as pathological family process. Second, the results of this study suggest that clinicians should be particularly sensitive to expectations that children provide emotional caretaking to an adult because, across social contexts, those demands, when excessive, may be most noxious to the well-being of children. Finally, the results of this study suggest that clinicians should be sensitive to the possibility that, although extensive involvement in caretaking may contribute to both internalizing and externalizing pathology, that dimension of family process alone may not explain the presence of clinically significant disturbance in emotional, behavioral, or social adaptation. As Jurkovic (1997; Jurkovic et al., 2004) suggested, the critical problem may not be the extent to which children are involved in caregiving but the extent to which the caregiving occurs in an unsupportive, unresponsive, invalidating family environment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 DA10726 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We thank Karen D'Avanzo, PhD, and the research assistants who worked on this project for their assistance with the collection and management of the data presented in this article. We also thank Michelle Baker, MD, and Jacob Tebes, PhD, for permission to use the Child Caretaking Scale in this research, we thank the mothers and children who agreed to participate.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baker MS. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT: 1997. The search for mechanisms of resilience: Consideration of caretaking behavior by children of mentally ill mothers. [Google Scholar]

- Baker MS, Tebes JK. The Child Caretaking Scale. Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bedeian AG, Mossholder KW. Simple question, not so simple answer: Interpreting interaction terms in moderated multiple regression. Journal of Management. 1994;20:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bekir P, McLellan T, Childress AR, Gariti P. Role reversals in families of substance abusers: A transgenerational phenomenon. International Journal of the Addictions. 1993;28:613–630. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boszormenyi-Nagy I, Spark GM. Invisible loyalties: Reciprocity in intergenerational family therapy. Harper & Row; Hagerstown, MD: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chase ND. Parentification: An overview of theory, research, and societal issues. In: Chase ND, editor. Burdened children: Theory, research, and treatment of parentification. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chase ND. Parentified children grow up: Dual patterns of high and low functioning. In: Robinson BE, Chase ND, editors. High-performing families: Causes, consequences and clinical solutions. American Counseling Association; Alexandria, VA: 2001. pp. 157–189. [Google Scholar]

- Chase ND, Deming MP, Wells MC. Parentification, parental alcoholism, and academic status among young adults. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1998;26:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Head MR, Bumpus MF, McHale SM. Household chores: Under what conditions do mothers lean on daughters? In: Fuligni AJ, editor. Family obligation and assistance during adolescence: Contextual variations and developmental implications. New directions for child and adolescent development. Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 23–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolgin KG. Parents’ disclosure of their own concerns to their adolescent children. Personal Relationships. 1996;3:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Earley L, Cushway D. The parentified child. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Fullinwider-Bush N, Jacobvitz DB. The transition to young adulthood: Generational boundary dissolution and female identity development. Family Process. 1993;32:87–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1993.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzach Y. Misleading interaction and curvilinear terms. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Godsall RE, Jurkovic GJ, Emshoff J, Anderson L, Stanwyck D. Why some kids do well in bad situations: Relation of parental alcohol misuse and parentification to children's self-concept. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:789–809. doi: 10.1081/ja-120034016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ, Cohen L. Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:999–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM. Should we stay together for the sake of the children? In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with divorce, single parenting, and remarriage: A risk and resiliency perspective. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz DB, Bush N. Reconstructions of family relationships: Parent–child alliances, personal distress, and self-esteem. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:732–743. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz DB, Morgan E, Kretchmar M, Morgan Y. The transmission of mother–child boundary disturbances across three generations. Developmental and Psychopathology. 1991;3:513–527. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JR. Role diffusion and role reversal: Structural variations in divorced families and children's functioning. Family Relations. 1990;15:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ. Lost childhoods: The plight of the parentified child. Brunner-Routledge; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Kuperminc GP, Perilla J, Murphy A, Ibanez G, Casey S. Ecological and ethical perspectives on filial responsibility: Implications for primary prevention with Latino adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25:81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Kuperminc GP, Sarac T, Weisshaar D. Role of filial responsibility in the post-war adjustment of Bosnian young adolescents. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2005;5:219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Morrell R, Casey S. Parentification in the lives of high-performance individuals and their families: A hidden source of strength and distress. In: Robinson BE, Chase ND, editors. High-performing families: Causes, consequences and clinical solutions. American Counseling Association; Alexandria, VA: 2001. pp. 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Thirkield A, Morrell R. Parentification of adult children of divorce: A multidimensional analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Revisiting the construct of boundary dissolution: A multidimensional perspective. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2005;5:5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner SS, Wallace S, Lehman SJ, Lee SA, Escalante KA. Sensitive mother-to-adolescent disclosures after divorce: Is the experience of sons different from that of daughters? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:46–57. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:701–736. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]