Abstract

Neutrophils are highly specialized innate immune effector cells that evolved for antimicrobial host defense. In response to inflammatory stimuli and pathogens, they form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which capture and kill extracellular microbes. Deficient NET formation predisposes humans to severe infection, but, paradoxically, dysregulated NET formation contributes to inflammatory vascular injury and tissue damage. The molecular pathways and signaling mechanisms that control NET formation remain largely uncharacterized. Using primary human neutrophils and genetically manipulated myeloid leukocytes differentiated to surrogate neutrophils, we found that mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulates NET formation by posttranscriptional control of expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1α), a critical modulator of antimicrobial defenses. Next-generation RNA sequencing, assays of mRNA and protein expression, and analysis of NET deployment by live cell imaging and quantitative histone release showed that mTOR controls NET formation and translation of HIF-1α mRNA in response to lipopolysaccharide. Pharmacologic and genetic knockdown of HIF-1α expression and activity inhibited NET deployment, and inhibition of mTOR and HIF-1α inhibited NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing. Our studies define a pathway to NET formation involving 2 master regulators of immune cell function and identify potential points of molecular intervention in strategies to modify NETs in disease.

Introduction

Neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes, PMNs) are key effector cells in infection, inflammation, and tissue injury.1 Formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), first identified with human PMNs, is a function of neutrophils.2 NETs are complex lattices of decondensed chromatin that trap and kill bacteria, fungi, and some parasites by exposing them to high concentrations of NET-associated microbicidal factors.3,4 Rapidly evolving studies indicate that NETs effect extracellular microbial killing while limiting the spread of pathogens in vivo.3,5

The intracellular signaling pathways that regulate NET formation by PMNs remain largely unknown. There is evidence that generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a key event.4,6 Nevertheless, we showed in primary human PMNs that NET formation requires signaling events and regulatory pathways in addition to ROS generation.4 Consistent with our results, subsequent studies in human HL-60 myeloid leukocytes and genetically altered mice indicate that activity of peptidylarginine deiminase 4, an enzyme responsible for chromatin decondensation, is also required.5,7 Recent observations further suggest that NET formation requires enzymatic activity of neutrophil elastase (NE) and myeloperoxidase to initiate degradation of core histones that lead to chromatin decondensation before plasma membrane rupture.8 Furthermore, ROS generation and NET formation can be dissociated under some conditions.9,10 Thus, molecular regulation of NET formation is complex and may involve multiple signaling pathways and effector events, depending on the neutrophil agonists and inflammatory context.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a highly conserved PI3K-like serine/threonine kinase with functional homologs found in all studied eukaryotic organisms.11 mTOR integrates nutrient, energy, oxygen sensing, and mitogenic input signals.12 We found that mTOR also responds to inflammatory signals and mediates a previously unrecognized pathway of posttranscriptional gene regulation in human PMNs.13 These results identified a new mechanism by which mTOR can regulate innate, as well as, adaptive, immune responses. Immunoregulatory activities of mTOR are now increasingly recognized.14

Recent observations indicate that hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), the regulated subunit of the transcription factor HIF-1, is a novel “command and control” protein in activities of myeloid leukocytes. In a murine model, conditional deletion of HIF-1α resulted in decreased glycolytic capacity with dramatically reduced cellular ATP levels, leading to impaired myeloid leukocyte aggregation, motility, extravasation, and microbial killing.15 In additional murine studies, bacterial infection induced expression of HIF-1α in macrophages even in the absence of hypoxia,16 a key environmental regulator of HIF-1α accumulation in tumor cells and other cell types.17 Bacterial infection also triggered HIF-1α–dependent synthesis of antimicrobial products, granule proteases, nitric oxide, and cytokines, and deletion of HIF-1α in mice decreased bactericidal capacity and resulted in systemic spread of pathogens.16 HIF-1α has thus been termed a “master regulator” of innate host defense responses.18 Nevertheless, the activities of HIF-1α in human neutrophils remain largely uncharacterized, and nothing is known about its roles in the regulation of NET formation by human PMNs.

Here, we report that mTOR regulates NET formation by human PMNs through induction of HIF-1α protein expression and show that inhibition of mTOR and HIF-1α signaling in these immune effector cells leads to decreased bacterial killing. Our findings identify a previously unrecognized pathway to NET formation with key nodal points of biologic control and potential for therapeutic manipulation. The importance of these observations may extend to NET-mediated vascular injury and inflammatory tissue damage.19

Methods

Reagents

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Escherichia coli serotype 0111:134), poly-L-Lysine, Cytochalasin B, Cytochalasin D, glucose oxidase, paraformaldehyde, and N-(Methoxysuccinyl)-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val 4 nitroanilide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Additional reagents included 2-methoxyestradiol (Sigma-Aldrich), rapamycin, diphenylene iodonium (DPI; Calbiochem), torin 1 (a generous gift from the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), TOPRO-3, DNA standard (Invitrogen), Syto Green and Sytox Orange (Molecular Probes), DNase (Promega), Anti-CD15+ impregnated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), medium 199 (Lonza Biologics), micrococcal DNase (Worthington Biochemical), and platelet-activating factor (PAF; Avanti Lipids).

PMNs and surrogate PMN isolation

PMNs were isolated from acid-citrate dextrose anticoagulated venous blood of healthy adults under protocols approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. PMN suspensions (> 96% pure) were prepared by positive immunoselection with the use of anti-CD15–coated microbeads and an auto-MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) and were resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/mL concentration in serum-free M-199 media at 37°C.

HL-60 cells were obtained from ATCC and differentiated into surrogate PMNs with the use of 1.3% DMSO treatment over 5 days as previously described.13 Surrogate PMNs were then resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL in serum-free M-199 media at 37°C.

Genetic inhibition of HIF-1α via shRNA targeting of HIF-1α mRNA

We transduced undifferentiated HL-60 leukocytes via lentiviral infection with pLVTHM-GFP plasmids20 modified to constitutively express a short hairpin loop inhibitory-RNA (shRNA) against HIF-1α mRNA transcripts (www.genelink.com/siRNA/shrnaconstruct.asp; sequence: sense, 5′-caccggttaggtaatctggtaaggacgaatccttaccagattacctaacc-3′; antisense, 5′-aaaaggttaggtaatctggtaaggattcgtccttaccagattacctaacc-3′). As a control, PLVTHM-GFP was modified with a scrambled shRNA. Twenty-four hours after lentiviral transduction, the undifferentiated HL-60 cells were underwent FACS on the basis of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression. High GFP-expressing cells were then differentiated as described in the previous section and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL in serum-free M-199 media at 37°C in preparation for various assays described below.

HIF-1α transcript characterization using RNA-seq and qPCR in PMNs and surrogate PMNs

The expression and sequence of mRNA coding for HIF-1α in adult human PMNs were determined with paired-end next-generation RNA sequencing, as previously described with the use of the Illumina GAIIx sequencer with the assistance of the University of Utah Bioinformatics core,21 and quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the following primer sets: HIF-1α sense (5′-agagccgcttcatttcttaga-3′) and antisense (5′-tatccaaatcaccagcatcca-3′) and GAPDH sense (5′-gaacatcatccctgcctctactg-3′) and antisense (5′-agcttgacaaagtggtcgttgag-3′). The estimated secondary structure energy of the HIF-1α 5′–untranslated region (UTR) was determined with the Vienna RNA Websuite.22

Assessment of HIF-1α protein expression in PMNs and surrogate PMNs

We assessed HIF-1α protein expression in human PMNs and SC Control and HIF-1αKD surrogate PMNs with the use of the In-Cell Western technique with a primary antibody against human HIF-1α protein (Novus Biologicals) and an 800-nm secondary antibody (Li-Cor Biosciences) on an Odyssey Infrared scanner (Li-Cor Biosciences). Sapphire700 dye (Li-Cor Biosciences) uptake allowed for normalization to cell number in these assays. In selected experiments, HIF-1α protein expression was also quantified with quantitative immunocytochemistry and ImageJ Version 1.46 (National Institutes of Health) image analysis software.

To show mTOR-dependent, translational regulation of HIF-1α protein expression, we pretreated human PMNs with either rapamycin (200nM), torin 1 (250nM), or cycloheximide (500nM) for 1 hour before a 1-hour incubation with LPS (100 ng/mL) or PAF (10nM) in 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. The cells in each well were then fixed (2% p-formaldehyde) and permeablized (0.1% Triton X-100). Imaging and fluorescence quantitation were performed with the Odyssey Imaging system and Version 3.0 software (Li-Cor Biosciences). We used the same technique to show inhibition of HIF-1α protein expression in HIF-1αKD surrogate PMNs.

Live cell imaging

Primary or surrogate PMNs (2 × 106 cells/mL) were incubated with control buffer or stimulated with LPS (0.1-100 ng/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air on glass coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine and imaged with an Olympus FV300 1 × 81 confocal microscope and FluoView Version 2.1c software as previously described.4 NETs were detected with a mixture of cell permeable (Syto Green; Molecular Probes) and impermeable (Sytox Orange; Molecular Probes) DNA fluorescent dyes. For selected experiments, primary or surrogate PMNs were preincubated with rapamycin (200nM), FK-506 (200nM), 2 methoxyestradiol (2-ME2; 2μM), vinblastine (10μM), or paclitaxol (10μM) for 1 hour before imaging.

Quantitation of NET formation: supernatant histone H3 content

We determined supernatant total histone H3 content as follows. After live cell imaging of control and LPS-stimulated primary or surrogate PMNs (2 × 106/mL; 100 ng/mL), the cells were incubated with new media containing DNase (40 U/mL) for 15 minutes at room temperature to break down and release NETs formed in response to LPS stimulation. The supernatant was gently removed and centrifuged at 420g for 5 minutes. The cell-free supernatant was then mixed 3:1 with 4× Laemelli buffer before Western blot analysis. We used a polyclonal primary antibody against human histone H3 protein (Cell Signaling Technology) and infrared secondary antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences). Imaging and densitometry were performed on the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences). Comparison of histone H3 quantitation with other surrogates for NET formation4 is shown in supplemental Figure 2 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Bacterial killing assay

We determined bacterial killing efficiency of primary and surrogate PMNs as previously described.4 Leukocytes were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air alone or with the phagocytosis inhibitors Cytochalasin B and D (10μM). The leukocytes were then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL), placed in poly-L-lysine–coated wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate, and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour to induce cellular activation and formation of NETs. To inhibit NET-mediated bacterial killing, we incubated selected wells with DNase (40 U/mL) for 15 minutes before adding bacteria. E coli (1 colony forming unit/100 PMNs) were added to the PMNs, followed by continued incubation for 2 hours. The PMNs were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, and each well was scraped to free all cells. Serial dilutions were performed, and bacterial cultures were grown on 5% sheep blood agar plates (Hardy Diagnostics). After a 24-hour incubation, bacterial counts were determined. Total, phagocytotic, and NET-mediated bacterial killing were determined as described.4

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 11.0 (Stata Corporation) and Prism 5.02 (GraphPad software). Descriptive statistics are reported as the mean ± SEM. For parametric results that compared 2 groups, we used an unpaired, single-tailed Student t test, whereas the 1-way ANOVA with Tukey Multiple Comparisons posthoc testing was used for comparison of 3 or more groups. For nonparametric results that compared 2 groups we used the 2-sample Wilcoxon rank sum test, and for 3 or more groups we used the Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test with 2-sample Wilcoxon rank sum post hoc testing. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

mTOR regulates NET formation by human PMNs

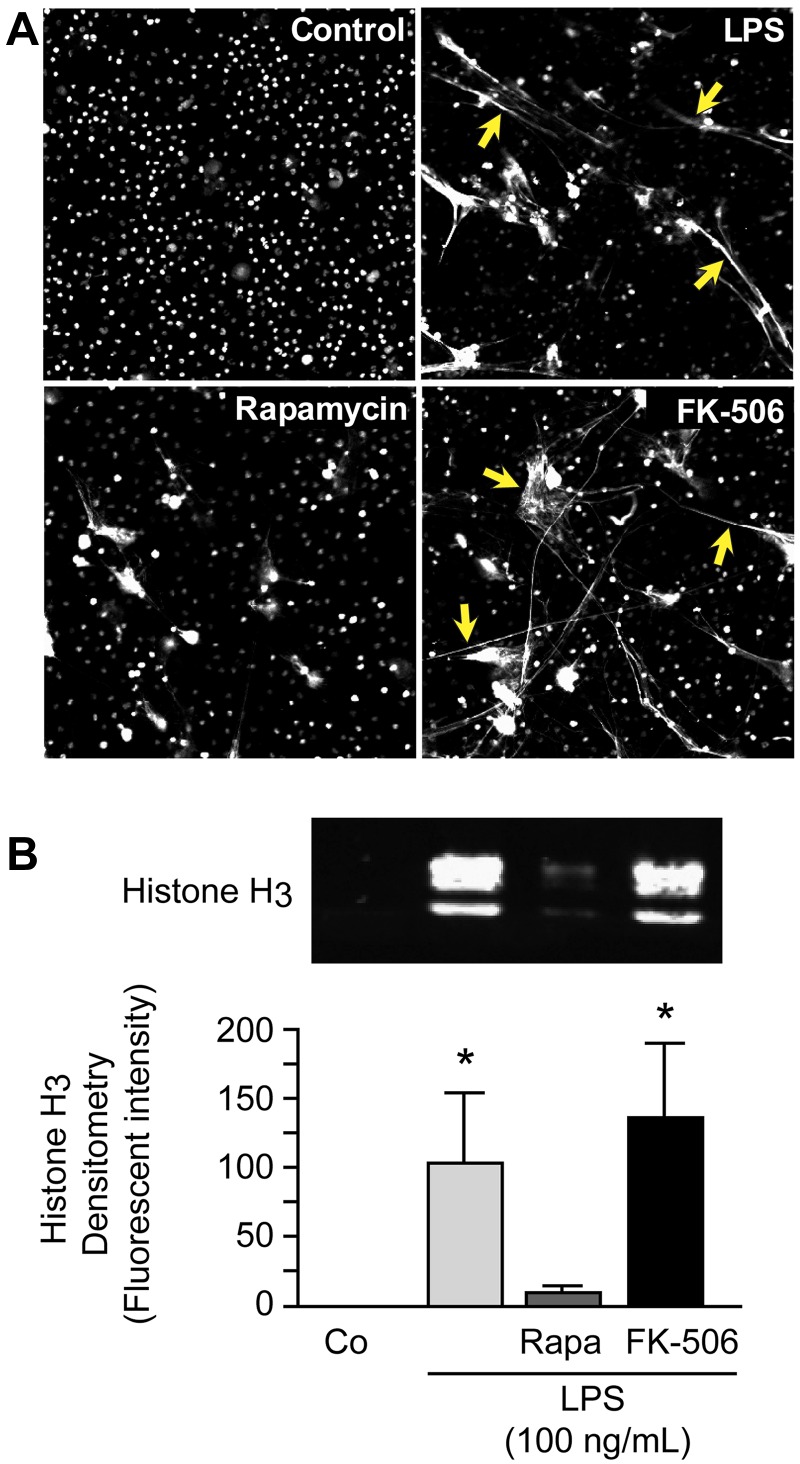

We first determined whether specific pharmacologic knockdown of mTOR activity with rapamycin23 altered NET formation by stimulated PMNs assessed by direct microscopic observation as previously described.4 We found that rapamycin, a selective blocker of mTOR activity,24 inhibits assembly of NETs by PMNs stimulated with LPS, whereas FK-506 did not (Figure 1A). FK-506, like rapamycin, binds to the regulatory molecule FKBP12, but in contrast, does not inhibit mTOR activity,25 and thus served as a control. In a complementary strategy that used genetic manipulation, we also attempted to silence mTOR in differentiated HL-60 surrogate PMNs with the use of siRNA. The cells with mTOR knocked down, however, repeatedly failed to divide and grow, consistent with known activities of mTOR12; therefore, experiments that examined NET formation under these conditions could not be accomplished. NETs are 3-dimensional structures that, in principal, must be visually assayed. Nevertheless, markers such as NE activity and extracellular DNA associated with NETs are used as surrogate assays for NET formation.4,6 We used histone release in this fashion and found that treatment of PMNs with rapamycin inhibited release of histone H3 by LPS-stimulated PMNs, whereas the control agent FK-506 did not (Figure 1B). These are the first observations that link the mTOR signaling pathway to NET formation.

Figure 1.

Rapamycin inhibits NET formation by human PMNs. (A) NET formation was assessed by live cell imaging with confocal microscopy (magnification, ×20). Extracellular and intracellular DNA were detected with a combination of cell permeable and cell impermeable DNA dyes (grayscale). Yellow arrows highlight areas of NET formation. Human PMNs were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour with or without pretreatment with rapamycin (200nM) or FK-506 (200nM) as a control for rapamycin. These images are representative of visual fields selected from randomly captured fields from assays performed with PMNs from 5 different adult donors. (B) We quantified extracellular histone H3 content in DNase-treated supernatants by Western blotting as a surrogate for NET formation by human PMNs. Human PMNs were stimulated as above. The image is representative of assays performed with human PMNs isolated from 4 different healthy adult donors with densitometry analysis (n = 4) indicated in the graph below. Columns represent mean ± SEM supernatant histone H3 fluorescent intensity. The Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test with 2-sample Wilcoxon rank sum posthoc testing was used. *Statistical significance with P < .05 in comparison with both control and LPS/rapamycin samples.

We have previously shown that mTOR exerts specialized translational control and regulates synthesis of key proteins in activated human PMNs.13 Furthermore, mTOR regulates specialized translation in other cell types.11,12 We considered HIF-1α a candidate for specialized posttranscriptional regulation by mTOR.

mTOR is a posttranscriptional regulator of HIF-1α protein expression in human PMNs

We first probed HIF-1α messenger RNA (mRNA) transcript structure and expression in control and stimulated human PMNs with the use of paired-end next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and qPCR.21 mRNA for full-length HIF-1α was present in freshly isolated, unstimulated PMNs (Figure 2A top). Consistent with this, HIF-1α protein was also basally present under normoxic conditions (Figures 2D-E and 3A). Analysis of HIF-1α transcript expression after stimulation with LPS showed a less than 1.5-fold increase in multiple experiments (Figure 2A top, C). In contrast, there was a 2- to 4-fold increase in HIF-1α protein expression (Figure 2D-E), even though the increase in HIF-1α mRNA was minimal, a pattern indicating a major element of posttranscriptional control.26 For comparison, we found a 5- to 8-fold increase in interleukin 8 (IL-8) mRNA expression in response to stimulation of PMNs under the same conditions (Figure 2A bottom). In previous experiments, we have shown that IL-8 protein synthesis is regulated by transcription in activated human PMNs.13,27

Figure 2.

HIF-1α protein accumulation is posttranscriptionally regulated by mTOR in LPS-stimulated human PMNs. (A) We assessed HIF-1α (top) and IL-8 (bottom) transcript expression with the use of RNA-seq in control and stimulated human PMNs isolated from a single healthy adult donor. (B) Using RNA-seq, we determined the sequence of the 5′-UTR for the transcript coding for HIF-1α and predicted both its secondary structure (image) and the energy required to resolve its secondary structure (−182.4 kcal/mole).22 (C) qPCR was used to assess HIF-1α mRNA transcript expression in PMNs isolated from 3 different healthy adults at baseline and after LPS-stimulation over 1 hour. The results are presented as fold change over baseline ± SEM with baseline HIF-1α mRNA expression arbitrarily set at 1 (dashed line). One-way ANOVA analysis found no statistically significant differences. (D) We determined HIF-1α protein accumulation using In-Cell Western analysis for PMNs isolated from healthy adults at baseline and after LPS-stimulation for 1 hour with or without 1-hour pretreatment with rapamycin (200nM) or cycloheximide (500nM). The results are presented as fold change over baseline with baseline HIF-1α expression arbitrarily set at 1. The 1-way ANOVA with Tukey Multiple Comparisons posttesting was used. These results are representative of 5 separate experiments performed with human PMNs isolated from 5 different healthy adult donors. Statistical significance with *P < .05 and **P < .001. (E) We again assessed HIF-1α protein accumulation using In-Cell Western techniques in PMNs isolated from healthy adults at baseline and after LPS-stimulation for 1 hour with or without 1-hour pretreatment with rapamycin (200nM), torin 1 (250nM), or cycloheximide (500nM). The results are presented as absolute fluorescence normalized to cell number and are representative of 2 separate experiments performed with human PMNs isolated from 2 different healthy adult donors. (F) Human PMNs were stimulated with PAF (10nM) for 1 hour after a 1-hour pretreatment with or without rapamycin (200nM) or FK-506 (200nM). HIF-1α protein expression was quantified with semiquantitative immunocytochemistry, and the columns represent the mean fold change over baseline ± SEM. Control HIF-1α protein expression was arbitrarily set at 1 (dashed line). We used the single tailed Student t test for statistical analysis. *Significant difference (P < .05) between samples from PAF-stimulated PMNs and rapamycin-pretreated, PAF-stimulated PMNs. These experiments were performed with PMNs isolated from 3 different healthy adult donors.

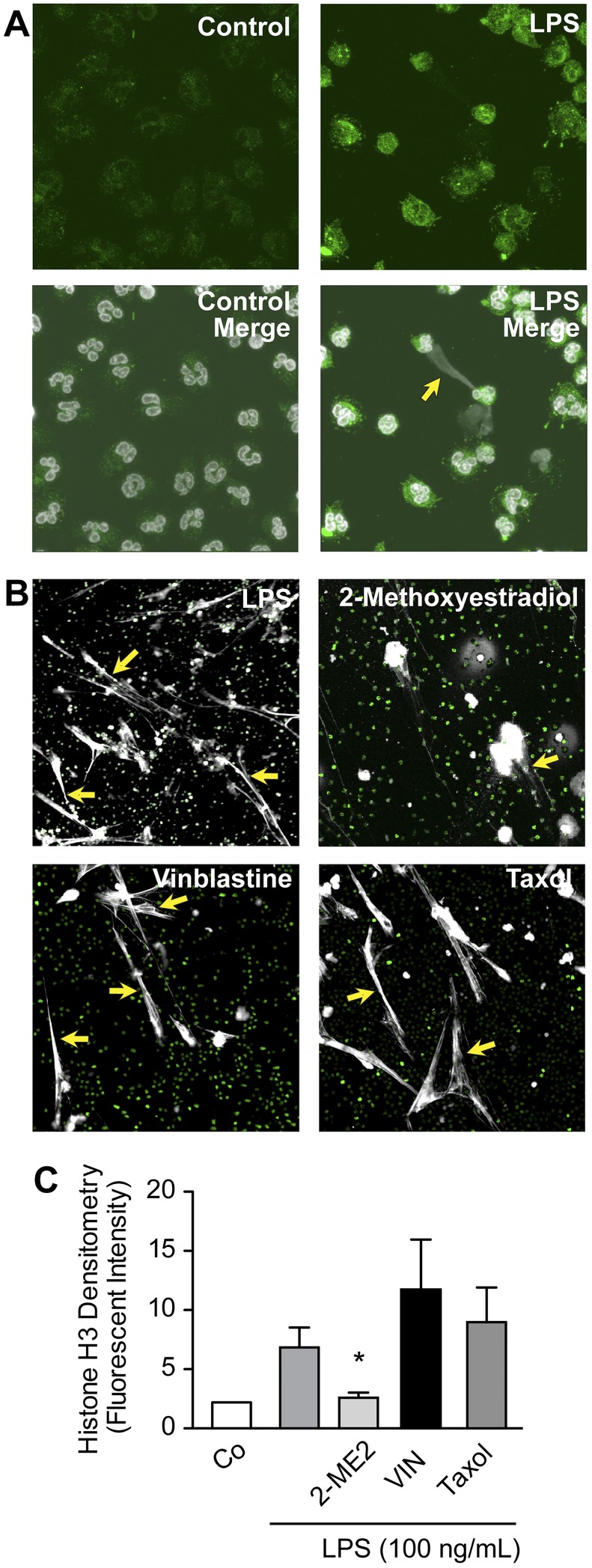

Figure 3.

Pharmacologic inhibition of HIF-1α activity decreases NET formation by LPS-stimulated human PMNs. (A) HIF-1α protein expression and NET formation were simultaneously assessed with immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy (magnification, ×60) in LPS-stimulated human PMNs (100 ng/mL), conditions that induced HIF-1α protein (Figure 2D-E). HIF-1α protein expression is shown (green fluorescence). In the merged images (bottom), extracellular and intracellular DNA are detected with TOPRO-3 (grayscale), with the yellow arrow highlighting an area of robust HIF-1α expression and NET formation. (B) NET formation was assessed by live cell imaging with confocal microscopy (magnification, ×20). Extracellular and intracellular DNA were detected with a combination of cell permeable (nuclear DNA; green) and cell impermeable (extracellular DNA; grayscale) DNA dyes. Yellow arrows highlight areas of NET formation. Human PMNs were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour with or without pretreatment with 2-ME2 (2μM). Vinblastine (10μM) and paclitaxol (10μM), 2 inhibitors of microtubule function, served as controls for 2-ME2 pretreatment and its reported antimicrotubule activity. These images are representative of randomly selected visual fields of assays performed with PMNs from 5 different adult donors. (C) The columns represent mean ± SEM supernatant histone H3 fluorescent intensity from human PMNs isolated from 7 different healthy adult donors indicated in the graph below. The 2-sample Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. *Statistical significance with P < .05 in comparison with the LPS, vinblastine, and taxol samples.

We examined the sequence of the 5′-UTR of the HIF-1α transcript identified by RNA-seq in PMNs (Figure 2A) and found that it exhibited substantial complexity with a base pair length of 339 and estimated secondary structure energy of −182.4 kcal/mol (Figure 2B). These features are characteristic of transcripts whose translation is controlled by mTOR in nonimmune cells28 and in human PMNs.13 Consistent with this, treatment of PMNs with rapamycin inhibited increased HIF-1α protein expression in stimulated PMNs, as did cycloheximide (Figure 2D-E). In addition, a second selective inhibitor of mTOR complex 1 activity, torin 1, had a similar effect (Figure 2E). These results indicated that HIF-1α is downstream in a pathway regulated by mTOR in human neutrophils, a previously unrecognized signaling cascade in this cell type.

HIF-1α regulated NET formation by primary and surrogate PMNs

Conditions that induced NET formation by PMNs, including LPS stimulation, also induced HIF-1α protein expression (Figures 2–3A). Furthermore, PAF, an inflammatory agonist that activates mTOR in human PMNs13 and induces NET formation,4 stimulated expression of HIF-1α protein in an mTOR-dependent manner (Figure 2F). In addition, we found enhanced HIF-1α protein expression in PMNs in areas of active NET formation by immunocytochemical analysis (Figure 3A).

We next treated human PMNs with cobalt chloride, a hypoxia mimetic that increases cellular HIF-1α protein expression,29 and found it induced NET formation (supplemental Figure 5). To further examine this relation, we treated PMNs with 2-ME2, a chemotherapeutic inhibitor of HIF-1α signaling,30 and assayed NET formation both qualitatively and quantitatively. We found that 2-ME2 blocked NET formation by LPS-stimulated PMNs (Figure 3B-C). Antimicrotubule activities of 2-ME2 have also been reported,30 so we examined the effect of paclitaxol and vinblastine, known antimicrotubule agents, on NET formation. Neither drug inhibited NET deployment by stimulated PMNs (Figure 3B-C). Furthermore, 2-ME2 inhibited vascular endothelial growth factor transcript expression, a key downstream mRNA with expression dependent on the HIF-1 transcription factor, whereas vinblastine did not (supplemental Figure 4). We also found that inhibition of endogenous ROS with DPI failed to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor transcript expression, suggesting that ROS generation was not required for HIF-1α's activity as a subunit of the HIF-1 transcription factor (supplemental Figure 3). These experiments indicated that, in response to LPS, NETosis and NET formation31 involve signaling to HIF-1α.

We next sought to confirm the contribution of HIF-1α to NET formation by genetic inhibition. Because primary PMNs are not readily tractable to genetic manipulation, we used differentiated HL-60 leukocytes as surrogates for PMNs as previously described.13 As previously reported, we found that these cells form NETs in response to LPS stimulation (supplemental Figure 1).7 With the use of lentiviral infection to transduce undifferentiated HL-60 leukocytes,32 we inhibited HIF-1α protein expression with the use of shRNA constructs that target HIF-1α mRNA (HIF-1αKD). Constructs encoding a scrambled shRNA sequence served as controls (SC Control). Both lentiviral constructs constitutively expressed GFP as a marker of transduction. The HL-60 leukocytes were then differentiated into surrogate PMNs.7 We achieved a substantial reduction in HIF-1α protein expression in the HIF-1αKD cells compared with the SC Control cells under control and LPS-stimulated conditions (Figure 4A-B). We then assessed the ability of HIF-1αKD and SC Control surrogate PMNs to form NETs with the use of confocal microscopy and histone H3 quantitation. NET formation in HIF-1αKD cells was dramatically decreased after a 2-hour incubation with LPS compared with the SC Control cells assayed in parallel (Figure 4C-D). This result was consistent with pharmacologic knockdown of HIF-1α in primary human PMNs (Figure 3B-C). These results showed for the first time that HIF-1α regulates NET formation.

Figure 4.

Genetic inhibition of HIF-1α activity decreases NET formation by LPS-stimulated surrogate PMNs. (A) Differentiated HL-60 surrogate PMNs were transduced with a lentivirus designed to coexpress GFP (as a marker for transduction) and an shRNA targeting HIF-1α (HIF-1αKD) to inhibit HIF-1α expression. HL-60 surrogate PMNs transduced with GFP lentivirus encoding a scrambled shRNA served as controls (SC Control). HIF-1α protein expression was determined with the In-Cell Western technique. The results are presented as fluorescence/cell ± SEM. *P < .05. We used Student t test to compare HIF-1α protein expression in HIF-1αKD and SC Control cells. (B) We also compared LPS-stimulated HIF-1αKD and SC Control cell expression of HIF-1α protein with the use of semiquantitative immunocytochemistry. The results are presented as fold change over baseline fluorescence/cell ± SEM. *Statistical significance, P < .05, using Student t test. (C) We assessed NET formation by LPS-stimulated HIF-1αKD and SC Control surrogate PMNs with the use of live cell imaging with confocal microscopy (magnification, ×20). Extracellular DNA was detected with a cell impermeable DNA dye (extracellular DNA; grayscale). Green fluorescence represents GFP expression. Yellow arrows highlight areas of NET formation. (C) We used Western blotting to quantify extracellular histone H3 content in DNase-treated supernatants as a surrogate for NET formation by HIF-1αKD and SC Control cells. This image is representative of assays performed in surrogate PMNs isolated from 4 discrete differentiation cultures with densitometry readings from all experiments represented in the graph below. (D) Columns represent supernatant histone H3 fluorescent intensity ± SEM. The Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test with 2-sample Wilcoxon rank sum posthoc testing was used. *Statistical significance (P < .05) in comparison of both control and LPS-stimulated samples. The results presented in this figure represent at least 4 separate experiments performed with surrogate PMNs.

Pharmacologic and genetic inhibition of mTOR and HIF-1α signaling inhibit NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing

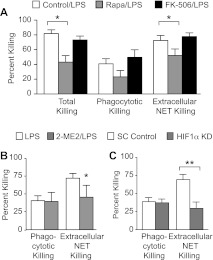

We next determined whether inhibition of mTOR signaling and HIF-1α activity decreased NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing. We first performed bacterial killing assays as previously described4 by incubating a pathogenic strain of E coli bacteria with LPS-stimulated primary human PMNs pretreated for 1 hour with either rapamycin or FK-506. Total and extracellular NET-mediated bacterial killings were significantly decreased in rapamycin-pretreated PMNs compared with FK-506–pretreated and control PMNs (Figure 5A). A trend toward decreased phagocytotic bacterial killing was also noted (Figure 5A). This result was consistent with inhibition of NET formation by rapamycin (Figure 1) and suggested that mTOR also regulated cellular pathways required for phagocytotic as well as NET-mediated, extracellular microbial killing.33

Figure 5.

Pharmacologic and genetic inhibition of mTOR and HIF-1α signaling inhibit NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing. (A) Total, phagocytotic, and extracellular NET-mediated bacterial killings by LPS-stimulated human PMNs (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour were determined with or without pretreatment with rapamycin (200nM; gray bars) or FK-506 (200nM; black bars). The bars indicate mean percentage of bacterial killing ± SEM in 10 separate experiments. *Statistically significant difference (P < .05) between the rapamycin-pretreated PMNs and both vehicle and FK-506 control preincubated PMNs in the both the Total and Extracellular NET Killing groups. We used the Student t test and Mann-Whitney statistical tests. (B) Phagocytotic and extracellular NET-mediated bacterial killings by LPS-stimulated human PMNs (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour were determined with or without 2-ME2 (2μM; gray bars) pretreatment. The bars indicate mean percentage of bacterial killing ± SEM in 4 separate experiments. *Statistically significant difference (P < .05) among the 2-ME2 pretreated, LPS-stimulated PMNs and LPS-stimulated PMNs. We used the Student t test for statistical analysis. (C) We determined phagocytotic and NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing in LPS-stimulated (100 ng/mL; 1 hour) HIF-1αKD and SC Control surrogate PMNs as described for panel A. The bars indicate mean percentage of bacterial killing ± SEM in 4 separate experiments. **P < .001. We used 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons posttesting.

In parallel experiments, we pretreated human PMNs with 2-ME2 for 1 hour before LPS stimulation and determined phagocytotic and extracellular NET-mediated bacterial killing as described above. We found that pharmacologic inhibition of HIF-1α activity significantly decreased NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing by 35% while not affecting phagocytotic bacterial killing (Figure 5B).

Finally, we determined whether genetic inhibition of HIF-1α protein expression affected extracellular NET-mediated bacterial killing. We incubated LPS-stimulated HIF-1αKD and SC Control cells with E coli bacteria as described above and determined phagocytotic and extracellular NET-mediated bacterial killing. We found significantly decreased NET-mediated extracellular bacterial killing in HIF-1αKD cells compared with the SC Control cells, with no difference detected in phagocytotic bacterial killing between the 2 groups of cells (Figure 5C). Thus, pharmacologic inhibition of HIF-1α in primary PMNs and genetic knockdown of HIF-1α in surrogate neutrophils inhibit NET-mediated bacterial killing.

Discussion

Although the importance of NET formation in protection from microbial invasion is well established,10,34,35 the pathologic power of dysregulated NET formation is now increasingly recognized. Dysregulated NET formation, occurring in response to pathologic stimuli, may contribute to sepsis,19 small vessel vasculitis,36 and systemic inflammatory response syndrome.19,37 Recent studies also document the importance of dysregulated NET formation in vascular injury associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.38,39 Yet the regulatory pathways governing NET formation remain incompletely characterized. Others have highlighted the importance of downstream effector molecules such as ROS, peptidylarginine deiminase 4, and the granule enzymes NE and myeloperoxidase for NET formation,5,6,8 but knowledge of the upstream regulatory molecules governing NET formation remains elusive.

Here, we link for the first time the mTOR signaling pathway to NET formation by human PMNs and characterize mTOR regulation of HIF-1α expression in primary human PMNs. Our findings also show for the first time that HIF-1α regulates NET formation and indicate that HIF-1α is downstream in a pathway regulated by mTOR in human neutrophils, a previously unrecognized signaling cascade in this critical immune effector cell. Earlier reports indicate that mTOR regulates HIF-1α protein accumulation and stability in cancer cells and cell lines,29,40–42 but this mechanism has not been previously demonstrated in primary human inflammatory cells. In other cell types, HIF-1α protein accumulation has additional complex regulatory elements, including alterations in proteolytic degradation.43,44 Thus, it may also be controlled at multiple checkpoints in PMNs, depending on the physiologic context.45

Our studies found that regulation of NET formation by mTOR operates at least in part through translational control of HIF-1α protein expression. Pharmacologic and genetic “knockdown” of mTOR and HIF-1α expression in primary human and surrogate PMNs result not only in decreased NET formation, assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively, but also in decreased NET-mediated antibacterial activity. Thus, 2 “master” molecular regulators, which are nodal points of cellular control that respond to a variety of inflammatory and metabolic signals, influence the deployment of NETs by human PMNs.

Our studies do not, however, determine the mechanism through which HIF-1α regulates NET formation. Although HIF-1α is widely recognized as the regulated subunit of the HIF-1 transcription factor which governs the cellular response to hypoxia, the rapidity of the PMN response to stimulation with NET formation suggests that other, more direct mechanisms may be at play. Of interest is the described role of HIF-1α in the regulation of ROS generation.46 Initial experiments in human PMNs found that treatment with exogenous ROS restores NET formation to PMNs pretreated with DPI, a pharmacologic inhibitor of NADPH oxidase.4,6

Our observations have translational relevance. Agents known to increase HIF-1α activity enhanced neutrophil bacterial killing in a previous study.44 The antimicrobial activity was extracellular and was eliminated by DNase treatment. This combination of characteristics is unique to NET-mediated antibacterial killing.2,4,6 Although no increase in NET formation was detected in that report,44 our findings suggest that HIF-1α is a point of molecular regulation of NET formation that may be positively manipulated by pharmacologic interventions in syndromes of microbial invasion or in syndromes of innate immune deficiency, such as the complex neutrophil dysfunction exhibited by human neonates.4 In parallel, identification of mTOR and HIF-1α as regulators of NET formation suggests that one or both may be molecular points of intervention in sepsis, lupus erythematosus, and vasculitis, where NET deployment appears to be injurious to the host rather than protective.19,36,38

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jenny Pearce, Alex Greer, and Diana Lim for their help with preparation of the manuscript and figures and Andrew Weyrich and Guy Zimmerman for advice and collaboration in the studies reported and for suggestions and editorial help during drafting of this manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant K08 HD049699, C.C.Y.), The Children's Health Research Center of the University of Utah, and the Primary Children's Medical Center Foundation (award to C.C.Y.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.M.M. performed, directed, and interpreted experiments and wrote major portions of the paper; M.J.C., E.A.E, J.W.G., and J.W.R. performed experiments, provided key experimental approaches, and/or interpreted data; M.T.R. provided statistical expertise and helped interpret data; and C.C.Y. provided overall direction for the project, reviewed and analyzed all experiments, wrote sections of the paper, and edited the entire paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian C. Yost, Pediatrics/Neonatology, University of Utah, Williams Building, 295 Chipeta Way, Salt Lake City, UT 84108; e-mail: christian.yost@u2m2.utah.edu.

References

- 1.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(3):173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Kockritz-Blickwede M, Nizet V. Innate immunity turned inside-out: antimicrobial defense by phagocyte extracellular traps. J Mol Med. 2009;87(8):775–783. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yost CC, Cody MJ, Harris ES, et al. Impaired neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation: a novel innate immune deficiency of human neonates. Blood. 2009;113(25):6419–6427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010;207(9):1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(2):231–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. 2009;184(2):205–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3):677–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow OA, von Kockritz-Blickwede M, Bright AT, et al. Statins enhance formation of phagocyte extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(5):445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcos V, Zhou Z, Yildirim AO, et al. CXCR2 mediates NADPH oxidase-independent neutrophil extracellular trap formation in cystic fibrosis airway inflammation. Nat Med. 2010;16(9):1018–1023. doi: 10.1038/nm.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster KG, Fingar DC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(19):14071–14077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.094003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yost CC, Denis MM, Lindemann S, et al. Activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes rapidly synthesize retinoic acid receptor-alpha: a mechanism for translational control of transcriptional events. J Exp Med. 2004;200(5):671–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson AW, Turnquist HR, Raimondi G. Immunoregulatory functions of mTOR inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(5):324–337. doi: 10.1038/nri2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, et al. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112(5):645–657. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peyssonnaux C, Datta V, Cramer T, et al. HIF-1alpha expression regulates the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(7):1806–1815. doi: 10.1172/JCI23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(11):851–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarember KA, Malech HL. HIF-1alpha: a master regulator of innate host defenses? J Clin Invest. 2005;115(7):1702–1704. doi: 10.1172/JCI25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13(4):463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiznerowicz M, Trono D. Conditional suppression of cellular genes: lentivirus vector-mediated drug-inducible RNA interference. J Virol. 2003;77(16):8957–8961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8957-8961.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowley JW, Oler A, Tolley ND, et al. Genome wide RNA-seq analysis of human and mouse platelet transcriptomes. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruber AR, Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Neubock R, Hofacker IL. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W70–W74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn188. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124(3):471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):729–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beretta L, Gingras AC, Svitkin YV, Hall MN, Sonenberg N. Rapamycin blocks the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and inhibits cap-dependent initiation of translation. EMBO J. 1996;15(3):658–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindemann SW, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Signaling to translational control pathways: diversity in gene regulation in inflammatory and vascular cells. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornton NL, Cody MJ, Yost CC. Toll-like receptor 1/2 stimulation induces elevated interleukin-8 secretion in polymorphonuclear leukocytes isolated from preterm and term newborn infants. Neonatology. 2011;101(2):140–146. doi: 10.1159/000330567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 2001;15(7):807–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.887201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laughner E, Taghavi P, Chiles K, Mahon PC, Semenza GL. HER2 (neu) signaling increases the rate of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) synthesis: novel mechanism for HIF-1-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(12):3995–4004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3995-4004.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mabjeesh NJ, Escuin D, LaVallee TM, et al. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(4):363–375. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wartha F, Henriques-Normark B. ETosis: a novel cell death pathway. Sci Signal. 2008;1(21):pe25. doi: 10.1126/stke.121pe25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonvillain RW, Painter RG, Adams DE, Viswanathan A, Lanson NA, Jr, Wang G. RNA interference against CFTR affects HL60-derived neutrophil microbicidal function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(12):1872–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez-Cambronero J. Rapamycin inhibits GM-CSF-induced neutrophil migration. FEBS Lett. 2003;550(1-3):94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00828-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Douda DN, Jackson R, Grasemann H, Palaniyar N. Innate immune collectin surfactant protein D simultaneously binds both neutrophil extracellular traps and carbohydrate ligands and promotes bacterial trapping. J Immunol. 2011;187(4):1856–1865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bianchi M, Hakkim A, Brinkmann V, et al. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood. 2009;114(13):2619–2622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schonermarck U, et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med. 2009;15(6):623–625. doi: 10.1038/nm.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1318–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011;187(1):538–552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(73):73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(20):7004–7014. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7004-7014.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernardi R, Guernah I, Jin D, et al. PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR. Nature. 2006;442(7104):779–785. doi: 10.1038/nature05029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas GV, Tran C, Mellinghoff IK, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mTOR in kidney cancer. Nat Med. 2006;12(1):122–127. doi: 10.1038/nm1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Land SC, Tee AR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is regulated by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) via an mTOR signaling motif. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(28):20534–20543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zinkernagel AS, Peyssonnaux C, Johnson RS, Nizet V. Pharmacologic augmentation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha with mimosine boosts the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(2):214–217. doi: 10.1086/524843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walmsley SR, Print C, Farahi N, et al. Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1alpha-dependent NF-kappaB activity. J Exp Med. 2005;201(1):105–115. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hervouet E, Cizkova A, Demont J, et al. HIF and reactive oxygen species regulate oxidative phosphorylation in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(8):1528–1537. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.