Abstract

Echinococcus multilocularis is a zoonotic parasite in wild canids. We determined its frequency in urban coyotes (Canis latrans) in Alberta, Canada. We detected E. multilocularis in 23 of 91 coyotes in this region. This parasite is a public health concern throughout the Northern Hemisphere, partly because of increased urbanization of wild canids.

Keywords: Echinococcus multilocularis, alveolar echinococcosis, coyotes, Canis latrans, Alberta, Canada, parasites, cestodes, zoonoses

Echinococcus multilocularis is the causative agent of alveolar echinococcosis in humans. This disease is a serious problem because it requires costly long-term therapy, has high case-fatality rate, and is increasing in incidence in Europe (1). This parasitic cestode has a predominantly wild animal cycle involving foxes (Vulpes spp.) and other wild canids, including coyotes (Canis latrans), as definitive hosts. However, it can also establish an anthropogenic life cycle in which dogs and cats are the final hosts. Rodents are the primary intermediate hosts in which the alveolar/multivesicular hydatid cysts grow and are often fatal. Humans are aberrant intermediate hosts for E. multilocularis (2).

In North America, E. multilocularis was believed to be restricted to the northern tundra zone of Alaska, USA, and Canada until it was reported in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from North Dakota, USA (3). This parasite has now been reported in the southern half of 3 provinces in Canada (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta) and in 13 contiguous states in the United States (1).

Foxes are the traditional definitive hosts for E. multilocularis worldwide. However, in North America, coyotes may be prominent hosts, particularly when they are more abundant than foxes. E. multilocularis was reported in 7 (4.1%) of 171 coyotes in the northcentral United States in the late 1960s (3), and subsequently prevalences ranging from 19.0% to 35.0% have been reported in coyotes in the central United States (4).

In Canada, E. multilocularis was detected in 10 (23.0%) of 43 coyotes in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba (5). In Alberta, 1 case was recorded from the aspen parkland in 1973 (5) but it was not found in coyotes from forested regions and southern prairies (6,7). Nonetheless, E. multilocularis is generally considered enzootic to central and southern Alberta on the basis of its prevalence in rodent intermediate hosts. During the 1970s, sixty-three (22.3%) of 283 deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) trapped in periurban areas of Edmonton were positive for alveolar hydatid cysts (8), and E. multilocularis was also detected in 2 deer mice collected <1.8 km from Lethbridge in southern Alberta (9).

Because mice and voles (family Cricetidae, including Peromyscus spp.) have been reported as main prey (70.1%) of coyotes in Calgary (10), and coyotes are common in urban areas of Calgary and Edmonton, we suspected a role for this carnivore in the maintenance of the wild animal cycle of E. multilocularis in such urban settings. Thus, we aimed to ascertain the frequency of E. multilocularis in coyotes from metropolitan areas in Alberta, Canada.

The Study

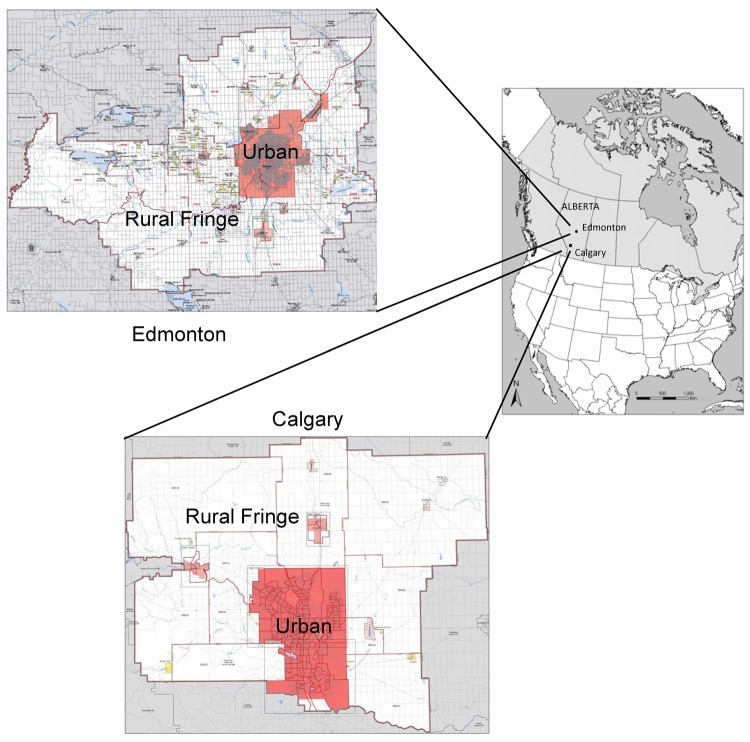

Ninety-one hunted or road-killed coyotes were collected during October 2009–July 2011. Most (n = 83) of the carcasses were from the Calgary census metropolitan area (CMA) (Figure 1). The remainder (n = 8) were opportunistically collected from the Edmonton CMA. Of those from the Calgary CMA, the exact location of collection was known for 60 animals: 27 were from Calgary and 33 were from the rural fringe, including 2 near Strathmore. Of the carcasses from the Edmonton CMA, 7 were from Edmonton and 1 was from a periurban site. Sex and age of 90 of the coyotes were recorded.

Figure 1.

Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, census metropolitan areas in which 91 coyote carcasses were collected during 2009–2011 and tested for Echinococcus multilocularis. Reference maps (2006) were obtained from the Geography Division, Statistics Canada (www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/geo/index-eng.cfm). Urban core areas and surrounding rural fringes are indicated. For Edmonton, 5 (62.5%) of 8 carcasses were positive. For Calgary, 18 (20.5%) of 83 carcasses were positive: 9 (27.3%) of 33 from the rural fringe, 4 (14.8%) of 27 from the urban area, and 5 (21.7%) of 23 whose locations of collection were not accurate enough to be classified as urban or from the rural fringe.

Before necropsy, all carcasses were stored at −20°C. Gastrointestinal tracts collected at necropsy were refrozen at −80°C for 3–5 days to inactivate Echinococcus spp. eggs. Once thawed and dissected, intestinal contents were washed, cleared of debris, and passed through a sieve (500-µm pores), and the material in the sieve was examined for Echinococcus spp.

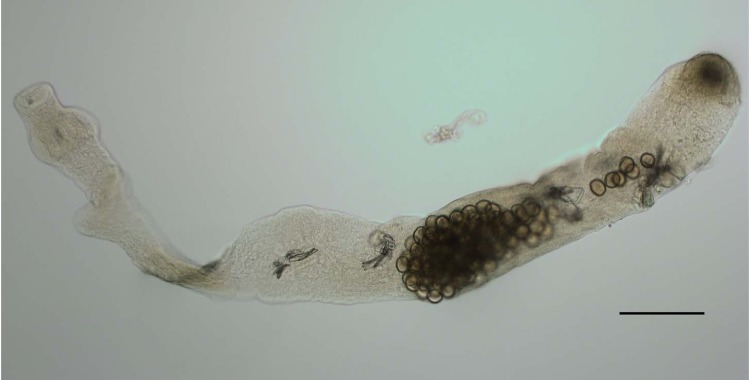

Adult tapeworms were counted and identified as E. multilocularis on the basis of morphologic features (Figure 2). To confirm morphologic identification, PCR was performed by using species-specific primers (11). Briefly, a representative adult worm from each positive animal was lysed in 50 μL of DNA extraction buffer (500 mmol/L KCl, 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 15 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mol/L dithiothreitol, and 4.5% Tween 20) containing 2 μL of proteinase K. This lysate was further diluted (1:20 in double-distilled water), and 2 μL was used for PCR. Amplicons of an expected 395 bp confirmed infection with E. multilocularis.

Figure 2.

Differential interference contrast micrograph of a representative Echinococcus multilocularis isolate from a coyote carcass in Alberta, Canada, October 2009–July 2011. The parasite was 2,059.72 μm long, as measured by using an Olympus BX53 microscope and software (http://microscope.olympus-global.com/en/ga/product/bx53/sf04.cfm). Scale bar = 200 μm.

E. multilocularis was identified in 23 (25.3%) of 91 coyotes by using morphologic and molecular identification. Among positive animals, 18 (20.5%) of 83 were from the Calgary CMA and 5 (62.5%) of 8 were from the Edmonton CMA. In the Calgary CMA, 4 (14.8%) of 27 positive animals were found in the city and 9 (27.3%) of 33 were found in the rural fringe (Figure 1). Five (21.73%) of 23 coyotes for which the location was not recorded were also positive.

E. multilocularis intensity (number of cestodes per host) ranged from 1 to 1,400 (median 20.5). The frequency of infection was significantly higher in male coyotes (n = 44, 34.19%) than in female coyotes (n = 46, 15.2%; χ2 4.337, df 1, Pexact = 0.05) (Table). No difference was detected between 43 juvenile coyotes and 47 adult coyotes (Table).

Table. Echinococcus multilocularis in coyotes carcasses collected in Calgary (n = 83) and Edmonton (n = 8) census metropolitan areas, Alberta, Canada, October 2009–July 2011*.

| Characteristic | Total | No. (%) positive or median (range) | No. negative | IQ distance | χ2 (z) | df | pexact value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex‡ | |||||||

| M | 44 | 15 (34.1) | 29 | ||||

| F | 46 | 7 (15.2) | 39 | NA | 4.337 | 1 | 0.05 |

| Parasite intensity | |||||||

| M | NA | 9 (1–1,400) | NA | 83 | |||

| F | NA | 59 (9–822) | NA | 137 | (−1.406) | 0.19 | |

| Age‡ | |||||||

| Juvenile | 43 | 14 (33.3) | 29 | NA | |||

| Adult | 47 | 8 (17.0) | 39 | NA | 1.661 | 1 | 0.226 |

| Parasite intensity | |||||||

| Juvenile | NA | 9 (1–151) | NA | 71 | |||

| Adult | NA | 32 (1–1,400) | NA | 520 | (−0.737) | 0.518 |

*Values in boldface indicate a significant difference. Higher prevalence in male coyotes suggests a role for sex in parasite dispersion. Frequencies of cestodes in males vs. females and juveniles vs. adults were analyzed by using χ2 test. Parasite intensity (no. parasites per host) among sex and age classes was compared by using Mann-Whitney test for independent samples. IQ, interquartile distance; NA, not applicable. †Probability of distribution was estimated by using the permutation approach (pexact). ‡Sex and age of 1 coyote were not recorded.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that E. multilocularis is common in coyotes of metropolitan areas of Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, including their urban cores. This finding might indicate an emerging phenomenon similar to that observed in Europe with infiltration of urban centers by E. multilocularis caused by an increase in red foxes in cities such as Copenhagen, Geneva, and Zurich (2). In Alberta, this phenomenon may be caused by coyotes occupying the urban landscape or by city sprawl invading the natural habitats of coyotes.

Our data suggest that E. multilocularis is enzootic in coyotes in Alberta and that perpetuation of the wild animal cycle of E. multilocularis within cities and surroundings and potential infection of domestic dogs may pose a zoonotic risk, as documented on Saint Lawrence Island, Alaska, and in China (2,12). With a considerable increase in domestic dog population of Calgary (32.1% increase since 2001, a total of 122,325 dogs in 2010; Animal and Bylaw Services Survey 2010, www.calgary.ca/CSPS/ABS/Pages/home.aspx) and substantial human population growth (32.9% increase in Calgary since 1999; Statistics Canada, 2009, www.statcan.gc.ca/start-debut-eng.html), awareness is needed of potential transmission risks associated with changing city landscapes and E. multilocularis in the urban environment.

In Canada, only 1 autochthonous human case of alveolar echinococcosis has been reported in Manitoba (13). However, imported cases have been described. In Alberta, there are no known reports of alveolar echinococcosis. This finding may be caused by the long incubation time required for clinical manifestation in humans (12) or a strain of E. multilocularis with a low zoonotic potential. Although there is little evidence of human risk from the strain of E. multilocularis in central North America (14), a human case caused by this strain has been confirmed (15).

Our finding of E. multilocularis in coyotes in urban regions in Alberta suggests that surveillance for this parasite should be increased in North America. Although removal of this parasite from domestic dogs and cats is effective, eradication from free-ranging definitive hosts may be unfeasible (2,12). Interventions other than improving public awareness about prevention and transmission risk are probably unnecessary, and public health messages should target veterinarians and dog owners because domestic dogs probably represent the main infection route for humans in North America (2,12). Genetic characterization of E. multilocularis and spatially explicit transmission models should also be developed to better assess risks of this emerging zoonosis in North America and worldwide.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bill Bruce, officers of the Animal and Bylaw Services of the city of Calgary, officers of the Alberta Fish and Wildlife and the Alberta Provinicial Parks, the Municipality District of Rocky View, City Roads of the City of Calgary, Colleen St. Claire and collaborators, and Mark Edwards for carcass collection; and Margo Pybus, Susan Cork, and William Samuel for helpful suggestions.

This study and A.M. were supported by the Animal and Bylaw Services of the city of Calgary and the Faculty of Veterinary Services of the University of Calgary. S.J.K was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Biography

Mr Catalano is enrolled in the MSc graduate program at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. His research interests include wildlife diseases and the ecology of parasites in wild animal communities.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Catalano S, Lejeune M, Liccioli S, Verocai GG, Gesy KM, Jenkins EJ, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis in urban coyotes, Alberta, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2012 Oct [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1810.120119

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:125–33. 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107–35. 10.1128/CMR.17.1.107-135.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiby PD, Carney WP, Woods CE. Studies on sylvatic echinococcosis. III. Host occurrence and geographic distribution of Echinococcus multilocularis in the north central United States. J Parasitol. 1970;56:1141–50. 10.2307/3277560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazacos KR. Cystic and alveolar hydatid disease caused by Echinococcus species in the contiguous United States. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2003;25(Suppl. 7A):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samuel WM, Ramalingam S, Carbyn L. Helminths of coyotes (Canis latrans Say), wolves (Canis lupus L.) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes L.) of southwestern Manitoba. Can J Zool. 1978;56:2614–7. 10.1139/z78-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes J, Podesta R. The helminths of wolves and coyotes from the forested regions of Alberta. Can J Zool. 1968;46:1193–203. 10.1139/z68-169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson RC, Colwell D, Shury T, Appelbee A, Read C, Njiru Z, et al. The molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium and Giardia infections in coyotes from Alberta, Canada, and observations on some cohabiting parasites. Vet Parasitol. 2009;159:167–70. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes JC, Mahrt JL, Samuel WM. The occurrence of Echinococcus multilocularis Leuckart, 1863 in Alberta. Can J Zool. 1971;49:575–6. 10.1139/z71-090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers GA, Barrett MW. Echinococcus multilocularis Leuckart, 1863 in rodents in southern Alberta. Can J Zool. 1974;52:1091. 10.1139/z74-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukasik VM, Alexander SM. Coyote diet and conflict in urban parks in Calgary, Alberta. Presented at: Canadian Parks for Tomorrow, 40th Anniversary Conference, May 8–11, 2008; University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trachsel D, Deplazes P, Mathis A. Identification of taeniid eggs in the faeces from carnivores based on multiplex PCR using targets in mitochondrial DNA. Parasitology. 2007;134:911–20. 10.1017/S0031182007002235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deplazes P, Knapen FV, Schweiger A, Overgaauw PA. Role of pet dogs and cats in the transmission of helminthic zoonoses in Europe, with a focus on echinococcosis and toxocarosis. Vet Parasitol. 2011;182:41–53. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James E, Boyd W. Echinococcus alveolaris: (with the report of a case). Can Med Assoc J. 1937;36:354–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hildreth MB, Sriram S, Gottstein B, Wilson M, Schantz PM. Failure to identify alveolar echinococcosis in trappers from South Dakota in spite of high prevalence of Echinococcus multilocularis in wild canids. J Parasitol. 2000;86:75–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamasaki H, Nakao M, Nakaya K, Schantz PM, Ito A. Genetic analysis of Echinococcus multilocularis originating from a patient with alveolar echinococcosis occurring in Minnesota in 1977. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:245–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]