Abstract

Introduction

Rarely, amyloidosis presents as a focal, macroscopic lesion involving peripheral neural tissues (amyloidoma). In all known reported cases, peripheral nerve amyloidomas have immunoglobulin light chain fibril composition and occurred in the context of paraproteinemia.

Methods

A 46 y.o. man presented with progressive insidious onset right lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy without paraproteinemia. MRI-targeted fascicular nerve biopsy was performed on an enlarged sciatic nerve after earlier distal fibular nerve biopsy was nondiagnostic. Laser dissected mass spectroscopy of the discovered amyloid protein was performed after immunohistochemistry failed to identify the specific amyloid protein. Complete gene sequencing of ApoA1 was performed.

Results

Only wild type ApoA1 amyloid was found in the congophilic component in the nerve.

Discussion

The case highlights the utility of MRI guided fascicular nerve biopsy combined with laser dissected mass spectrometric analysis. Importantly, the case expands the known causes of amyloidomas to include wild type ApoA1.

Keywords: Amyloidoma, Apolipoprotein A1, Peripheral neuropathy, Amyloidogenesis, Mass spectrometry

Introduction

Most commonly, amyloidosis of peripheral neural tissues is pathologically characterized by diffuse, microscopic, predominantly endoneurial deposition of amyloid protein.1,2 The dorsal roots and autonomic ganglia typically show early involvement, but deposition can extend to all nerve segments and nerve fiber types.3,4 These pathologic involvements most commonly manifest clinically as a length-dependent, sensory before motor neuropathy with prominent dysautonomia. Rarely, focal macroscopic deposition of amyloid, i.e. amyloidoma, can involve peripheral neural tissues, usually originating from vertebral bodies5,6 or within the Gasserian ganglia.7 There are very few reported cases of amyloidomas arising within peripheral nerve tissues of the extremities.8-11 In all amyloidomas reported to date, amyloid fibrils are composed of immunoglobulin light chains and have arisen in the context of known systemic monoclonal gammopathy.

Amyloid deposits comprised of non-variant protein are known to occur in chronic inflammatory conditions (secondary amyloidosis AA), where deposits are composed of serum protein A (SAA), and in senile systemic amyloidosis, where deposits are composed primarily of wild type transthyretin. Peripheral neural tissue involvement in such conditions is not described.12 All known cases of peripheral nervous system amyloidosis have occurred in the context of plasma cell dyscrasia (i.e. primary light chain amyloidosis AL) or inherited mutations of transthyretin, gelsolin, or ApoA1.13 Autonomic neuropathy has been reported in hereditary fibrinogen amyloidosis, but it has not been confirmed histopathologically in peripheral nerve.14,15 ApoA1 is by far the rarest of known causes of amyloid associated neuropathy. It invariably presents with kidney involvement as well as cardiac and cutaneous amyloid deposits.16,17 In amyloidosis, the amyloid fibrils are associated with other proteins, including heparan sulphate proteoglycan, laminin, collagen IV, serum amyloid P, and apolipoprotein E.12

Localized macroscopic amyloid deposition seen with amyloidomas directs attention to unsettled pathologic implications of amyloidogenesis. Specifically, whether amyloidomas represent a localized primary overwhelming of normal protein recycling processes versus a macroscopic “tombstone” remnant of a more primary pathologic process is unclear.18 The tendency for distribution of amyloid in certain tissues, including the peripheral nervous system, is poorly understood and may relate to the balance between each tissue’s ability to clear amyloidogenic proteins relative to its tendency to generate or accumulate them.16 Amyloidomas provide an extreme example of these issues.

We report a patient with lumbosacral radiculoplexus amyloidoma in which we utilized recently described mass spectrometry analysis19 to identify ApoA1 as the amyloid fibril of origin without systemic markers of paraproteinemia.

Case report

A 46 year-old right handed man had 5 years of slowly progressive right lower extremity symptoms and was previously well without history of neuromuscular disease. His first symptoms consisted of loss of feeling and tingling of the right lateral foot and leg. Six months subsequently he became aware of a slapping of his right foot as he walked. He then developed frequent cramping of his right calf and hamstrings which would wake him from sleep with occasional paroxysms of shock-like pain radiating from the buttock to the lower leg. The dorsiflexion strength of the right ankle progressively decreased over the following year to the point he was not able to ankle dorsiflex against gravity. He then gradually became aware of plantar flexion weakness such that he found it difficult to lift all his weight with that single ankle and foot against gravity. He noticed atrophy in his right buttock, posterior thigh, and leg. He was without symptoms in other extremities and denied sweat, erectile or orthostatic symptoms. He had an identical twin brother who was healthy, and there was no known family history of neuropathy, amyloidosis, or plasma cell dyscrasia.

MRI of the lumbosacral spine, lumbosacral plexus, and distal nerves showed marked enlargement and T2 hyperintensity of the right L4 through S3 segments extending proximally to the roots (figure 1), which were consistent with a right lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy involving the L4-S3 segments, lumbosacral plexus, sciatic and femoral nerves. No contrast enhancement was seen after gadolinium administration. Denervation edema and atrophy were seen in the gluteus maximus, the posterior thigh compartment, and the abductor muscles of the right thigh with trace adductor involvement. No abnormalities were detected on the left.

Figure 1.

3 Tesla MRI of the pelvis demonstrated marked enlargement and T2 hyperintensity of the right L4-S3 nerve roots (arrows), extending along the lumbosacral plexus to the level of the sciatic notch on axial (A) and coronal (B) images. Denervation edema and atrophy were seen in the right gluteus maximus (arrow head).

Nerve conduction studies performed 2 years from symptom onset showed a normal right tibial compound muscle action potential (CMAP), reduced right sural sensory nerve action potential (SNAP), absent right superficial fibular SNAP, and absent right fibular CMAP. The F-wave latency was prolonged in the right tibial nerve. Needle electromyography showed fibrillation potentials in the right tibialis anterior, and no motor unit potentials (MUPs) were recruited. Fibrillation potentials and large MUPs were noted in the right medial gastrocnemius, short head of the biceps, gluteus maximus, and gluteus medius. Vastus medialis needle examination was normal. Biopsy of the right fibular nerve at the level of the knee showed moderate, generalized axonal loss with Wallerian-degeneration but indicated no specific etiology for the neuropathic process.

Based on imaging characteristics, a working diagnosis of hypertrophic inflammatory neuropathy was made, and a course of 2 grams (grams/kg) of intravenous immuonoglobulin was initiated in divided doses over five days, followed one month later by a second identical course. No benefit was appreciated. He was referred for subspecialty peripheral nerve consultation in evaluation of this problem.

On neurologic examination 5 years from symptom onset, he had normal mental status, speech, and cranial nerve exam. Motor and sensory examination of the upper extremities and the left leg was unremarkable. In the right leg, he had marked atrophy of the buttocks, hamstrings, tibialis anterior, and calf muscles. He had MRC grade 4 strength of hip abduction sparing hip flexion, grade 4 strength of knee flexion, normal strength of knee extension and adduction, without movement in ankle dorsiflexion, toe extension, and eversion, and grade 3 strength of ankle inversion, toe flexion, and plantar flexion. Tendon stretch reflexes were mildly reduced at the right patellar tendon, moderately reduced at the right Achilles tendon and were normal elsewhere. Sensory examination demonstrated panmodal sensory loss of the dorsolateral foot and lower leg.

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis, immunofixation, light chain analyses, and plasma cell flow cytometry were normal and were repeatedly so on annual examination over three years. Other normal studies included a complete cell count and differential, electrolyte panel, serum antineuronal antibody panel, sedimentation rate, rheumatologic markers (ANCAs, RF, CCP antibodies), ganglioside antibody panel, PMP-22 gene analysis, serum Lyme disease Western blot, TSH, ACE level, renal and liver function studies, creatine kinase, vitamin B12, and folate levels. Cerebrospinal fluid showed protein of 36.6mg/dL, glucose of 64, normal cell count and cytology, and negative Lyme polymerase chain reaction. Congo red staining of subcutaneous fat aspirate showed no amyloid deposition. Peripheral blood, bone marrow aspirate, and biopsy of the iliac crest showed no morphologic or immunophenotypic findings of involvement by a plasma cell proliferative disorder, and bone marrow was normocellular (50%) with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. F-18 FDG PET/CT scan was performed from the orbits through the upper thighs on two occasions and showed no abnormal foci of FDG accumulation to suggest plasmacytoma.

A second nerve biopsy using a targeted fascicular approach facilitated by the described MRI imaging was obtained from the tibial division of the sciatic nerve just distal to the sciatic notch. Intraoperatively, the sciatic nerve appeared enlarged in a fusiform fashion over about 6cm, tapering distally. Teased fiber analysis showed only unclassifiable fibers with large amounts of adherent, flocculent material. Semithin sections stained with methylene blue demonstrated severely decreased myelinated fiber density in a diffuse pattern, and only occasional, thinly myelinated fibers were seen. A large collection of subperineurial mononuclear cells was seen on paraffin sections. Amorphous, acellular material was seen diffusely throughout the endoneurium and perineurium. It was Congo red positive and showed apple green birefringence with polarized light (figure 2). Numerous mononuclear cells containing intracellular inclusions with a Maltese cross pattern of birefringence were present throughout the endoneurium. Electron microscopy together with immunohistochemical staining (which included S100, EMA, KP-1, CD 163, and CD11C preparations) demonstrated many of the cells to be macrophages, each with a single, large intracellular aggregate of fibrous material arranged in a starburst-like pattern (figure 3). Some starburst aggregates were partially extracellular and were closely associated with macrophages or Schwann cells; others were extracellular and were apparently remote from any mononuclear cell. Immunohistochemical staining of the congophilic material was indeterminate for specific type, including preparations for transthyretin, IgG kappa, and IgG lambda. Serum amyloid protein (SAP) and ApoE staining were present.

Figure 2.

Osmificated teased fiber preparation (A) showed mostly empty fibers, often with adherent, amorphous, flocculent material. On methylene blue-stained epoxy-embedded semithin sections (B), a severely decreased density of myelinated fibers is seen, with only rare, intermediate sized fibers seen (arrow head), and frequent spherical aggregates of amorphous material (arrows). Congo red stained sections (C) revealed the endoneurium (asterisk) and perineurium (arrow) of some fascicles to be completely effaced by congophillic, amorphous material which was diffusely birefringent under polarized light (D), diagnostic of amyloidosis. A large, subperineurial collection of inflammatory cells was seen in one fascicle (arrow head – panel C) displacing surrounding amyloid.

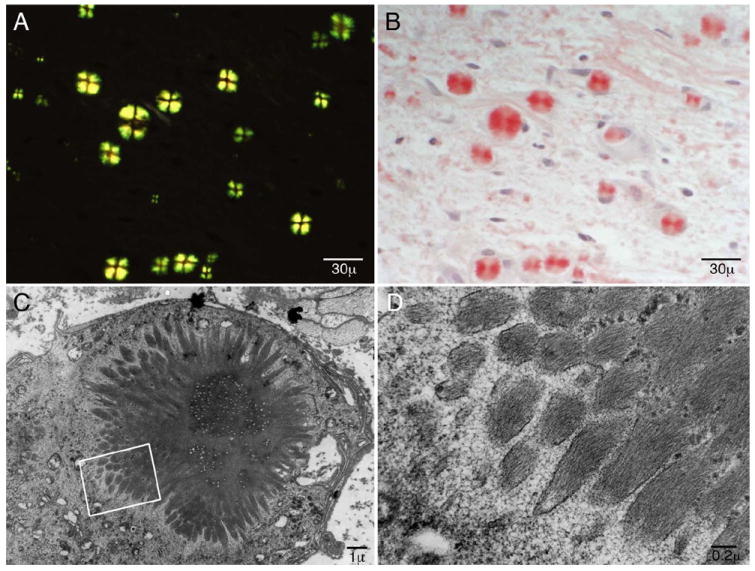

Figure 3.

The biopsied material showed frequent round intracellular inclusions scattered throughout the endoneurium which were congophilic (B) and displayed Maltese crosses with polarized light (A). Electron microscopy revealed starburst-shaped inclusions within mononuclear cells (C) demonstrated to be macrophages in conjunction with immunohistochemical preparations. At higher magnification (D) criss-crossing fibril formations typical of amyloid are seen.

To understand the protein composition of the amyloid deposit we isolated the proteins by laser microdissection, and after trypsin digestion we did liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry analysis (LMD-MS).17 The data was queried using three different algorithms (Mascot, Sequest and X!Tandem); the results were assigned peptide and protein probability scores and displayed using Scaffold (Proteome Software, Portland, OR). All known amyloid proteins and their associated proteins were queried. Only ApoA1 and serum SAP without other known amyloid or amyloid associated proteins were found. With the result, ApoA1 DNA mutations were sought, and complete sequencing of the entire open reading frame of the ApoA1gene was found to be normal.

Discussion

This patient had clinical imaging, intraoperative, and histologic findings of a peripheral nerve amyloidoma, with a previously undescribed composition of amyloid, consisting of isolated wild type ApoA1. Biopsy of the distal fibular nerve failed to identify the amyloid protein, whereas targeted proximal fascicular biopsy identified the pathologic amyloid component. There were no systemic markers of primary AL-amyloidosis by serial serologic, urine or bone marrow analyses or by nerve amyloid spectrometric-analysis. This case highlights the clinical utility of targeted fascicular nerve biopsy and laser microdissected mass spectrometry (LMD-MS) analysis in identifying and characterizing the composition of amyloid deposits. The use of immunohistochemistry to identify amyloid type was problematic in this patient’s nerve, as has been described previously.19,20 Through proteomic analysis of his biopsy, including evaluation for all known amyloid-associated and amyloidogenic proteins, ApoA1 was the identified amyloid protein. In this case no mutation was found in the ApoA1gene. The occurrence of a non-mutated accumulation of ApoA1 to our knowledge has not been reported in nerve amyloidosis.

ApoA1 amyloidosis is the rarest of known inheritable causes of peripheral nerve amyloidosis. Only an arginine for glycine substitution at position 26 (Gly26Arg) in the ApoA1gene on chromosome 11 (11q23) has been found to be associated with neuropathy.21 All instances of ApoA1 amyloidosis have been seen in heterozygotes in whom both wild type and variant ApoA1 are found in serum. The amyloid deposits, however, contain only the amino terminal 83-93 amino acid residues of the variant protein.13,22,23 This is in contrast to familial transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis, in which deposits contain 35-40% wild type TTR, a proportion which increases after orthotopic liver transplant.24-28 Non-variant TTR amyloid accumulation in isolation is reported in senile amyloidosis with heart failure.29

ApoA1 is produced mainly in the liver and intestine and is the major component of high density lipoprotein. It functions as both a cofactor for lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase and as a cholesterol transporter. In all cases of variant ApoA1 amyloidosis, mutations are thought to result in reconfiguration of the protein to the predominant B-helical structure requisite for formation of amyloid fibrils. Full length ApoA1 contains both alpha-helical and non-helical structure, as well as short sections of beta-pleated sheet.30 Conditions which have been shown to impart wild type ApoA1 with greater amyloidogenic potential include simple local displacement of ApoA1 from its associated lipoprotein particles 22 and methionine ApoA1 oxidation.31 Both of these processes are promoted by the inflammatory milieu, which may be the uniting characteristic of the few previous reports of wild-type ApoA1 amyloid deposition in atherosclerotic plaques,23,32,33 in pulmonary vasculature of aging dogs,34 and in the in the knee meniscus of patients undergoing surgery for degenerative arthropathy.35

A striking pathologic feature in our case was the abundance of birefringent macrophage inclusions demonstrating a Maltese cross appearance under polarized light. 36,37 This corresponds to radially-oriented amyloid fibrils that are seen within phagosomes of macrophages on electron microscopy (figure 3). Macrophage phagocytosis of amyloid 38-40 and spherulites composed of radially oriented accumulation of amyloid fibrils 36,41 have been infrequently described previously. The prominence of this unusual finding in our case might relate to the composition of amyloid fibrils with the ApoA1 wild type protein, possibly allowing for this vigorous, albeit futile, effort to clear the amyloid through normal targeting mechanisms. Furthermore, the biopsy seems to have captured a histologic snapshot of an active, vigorous process of phagocytosis and therefore likely contains both preprocessed and proteolyzed ApoA1. This may explain the presence of sequences both within and outside of the 93-residue amino terminal segment of ApoA1 previously reported to be amyloidogenic in all instances of both mutant and wild type ApoA1 amyloidosis. It is notable in our case that the perineurium, known to be a site of macrophage activation and senescence, is seen to be prominently involved by both amyloid deposits and inflammatory infiltrates. This lends further support to the hypothesis in this case that inflammation acted locally in combination with other amyloidogenic features to allow for the dramatic focal ApoA1 amyloidosis.

For clinicians, a consideration of amyloidoma in the differential diagnosis is problematic, especially in the absence of circulating monoclonal proteins, as was the case in our patient. Imaging led to consideration of a potentially treatable form of regional hypertrophic inflammatory neuropathy, and a prudent but unsuccessful immune treatment trial. Targeted biopsy combined with laser dissected mass spectrometric-analysis provided for the diagnosis. In our patient, orthopedic bracing and continued monitoring for development of a monoclonal gammopathy is planned. Currently there are no proven treatments for neural amyloidomas, including those with circulating monoclonal proteins.42 Hopefully, emerging new strategies to reduce associated amyloid proteins and hence the amyloid fibrils,43 and therapeutics to change energy kinetics away from the fibril forming constitutives44 may ultimately help such patients. Considering the reported proamyloidogenic effects on ApoA1 of local inflammatory processes such as atherosclerosis, future trends in treatment of similar patients might continue toward anti-inflammatory as well as statin and anti-oxidant medications.

Figure 4. ApoA1 Sequence and Identified Amino Acid Digests.

Mass spectrophotometry identified sequences throughout the ApoA1 protein, representing 113 of 267 of the total amino acids (i.e. 42% of the total protein, identified and highlight yellow). One oxidated methionine residue was identified (highlighted green). The identified sequences were both within and outside the 93 amino acid amino terminal segment previously identified as amyloidogenic.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Mayo Foundation Clinical Research Grant, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant (K08 NS065007-01A1)(NS36797).

Abbreviations

- ApoA1

Apolipoprotein A1

- TTR

transthyretin

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- MR

magnetic resonance

- Gly26Arg

glycine 26 arginine

- Leu178His

leucine 178 histidine

- WT

wild type

- PMP-22

peripheral myelin protein 22

- ANCA

anti neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- CCP

cyclic citrullinated peptide

- TSH

thyroid stimulating hormone

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- PET/CT

Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

- FDG

Fludeoxyglucose

- EMA

epithelial membrane antigen

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- SAP

serum amyloid P component

- SAA

serum amyloid A protein

- SNAP

sensory nerve action potential

- CMAP

compound muscle action potential

- MUP

motor unit potential

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- LMD-MS

laser microdissection mass spectroscopy

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- LCAT

lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement The authors have no financial disclosures related to the presented materials.

References

- 1.Adams D. Hereditary and acquired amyloid neuropathies. J Neurol. 2001 Aug;248(8):647–657. doi: 10.1007/s004150170109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RA, Bayrd ED. Amyloidosis: review of 236 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975 Jul;54(4):271–299. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197507000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyck PJ, Lambert EH. Dissociated sensation in amylidosis. Compound action potential, quantitative histologic and teased-fiber, and electron microscopic studies of sural nerve biopsies. Arch Neurol. 1969 May;20(5):490–507. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480110054005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyle A, Kelly JJ, Dyck PJ. Amyloidosis and neuropathy. In: Dyck P, editor. Peripheral Neuropathies. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2005. pp. 2427–2451. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haridas A, Basu S, King A, Pollock J. Primary isolated amyloidoma of the lumbar spine causing neurological compromise: case report and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2005 Jul;57(1):E196. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000163423.45514.bc. discussion E196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porchet F, Sonntag VK, Vrodos N. Cervical amyloidoma of C2. Case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998 Jan 1;23(1):133–138. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801010-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laeng RH, Altermatt HJ, Scheithauer BW, Zimmermann DR. Amyloidomas of the nervous system: a monoclonal B-cell disorder with monotypic amyloid light chain lambda amyloid production. Cancer. 1998 Jan 15;82(2):362–374. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980115)82:2<375::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Consales A, Roncaroli F, Salvi F, Poppi M. Amyloidoma of the brachial plexus. Surg Neurol. 2003 May;59(5):418–423. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00041-7. discussion 423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladha SS, Dyck PJ, Spinner RJ, et al. Isolated amyloidosis presenting with lumbosacral radiculoplexopathy: description of two cases and pathogenic review. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006 Dec;11(4):346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2006.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabet JY, Vital Durand D, Bady B, Kopp N, Sindou M, Levrat R. Amyloid pseudotumor of the sciatic nerve. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1989;145(12):872–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pizov G, Soffer D. Amyloid tumor (amyloidoma) of a peripheral nerve. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986 Oct;110(10):969–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyle RA. Amyloidosis: a convoluted story. Br J Haematol. 2001 Sep;114(3):529–538. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson MD, Kincaid JC. The molecular biology and clinical features of amyloid neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2007 Oct;36(4):411–423. doi: 10.1002/mus.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Carvalho M, Linke RP, Domingos F, et al. Mutant fibrinogen A-alpha-chain associated with hereditary renal amyloidosis and peripheral neuropathy. Amyloid. 2004 Sep;11(3):200–207. doi: 10.1080/13506120400000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stangou AJ, Banner NR, Hendry BM, et al. Hereditary fibrinogen A alpha-chain amyloidosis: phenotypic characterization of a systemic disease and the role of liver transplantation. Blood. 2010 Apr 15;115(15):2998–3007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-223792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benson MD. The hereditary amyloidoses. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003 Dec;17(6):909–927. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joy T, Wang J, Hahn A, Hegele RA. APOA1 related amyloidosis: a case report and literature review. Clin Biochem. 2003 Nov;36(8):641–645. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(03)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisilevsky R. Amyloids: tombstones or triggers? Nat Med. 2000 Jun;6(6):633–634. doi: 10.1038/76203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein CJ, Vrana JA, Theis JD, et al. Mass spectrometric-based proteomic analysis of amyloid neuropathy type in nerve tissue. Arch Neurol. 2011 Feb;68(2):195–199. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picken MM, Herrera GA. The burden of “sticky” amyloid: typing challenges. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007 Jun;131(6):850–851. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-850-TBOSAT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Allen MW, Frohlich JA, Davis JR. Inherited predisposition to generalized amyloidosis. Clinical and pathological study of a family with neuropathy, nephropathy, and peptic ulcer. Neurology. 1969 Jan;19(1):10–25. doi: 10.1212/wnl.19.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obici L, Franceschini G, Calabresi L, et al. Structure, function and amyloidogenic propensity of apolipoprotein A-I. Amyloid. 2006 Dec;13(4):191–205. doi: 10.1080/13506120600960288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teoh CL, Griffin MD, Howlett GJ. Apolipoproteins and amyloid fibril formation in atherosclerosis. Protein Cell. 2011 Feb;2(2):116–127. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1013-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herlenius G, Wilczek HE, Larsson M, Ericzon BG. Ten years of international experience with liver transplantation for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: results from the Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy World Transplant Registry. Transplantation. 2004 Jan 15;77(1):64–71. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000092307.98347.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liepnieks JJ, Wilson DL, Benson MD. Biochemical characterization of vitreous and cardiac amyloid in Ile84Ser transthyretin amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2006 Sep;13(3):170–177. doi: 10.1080/13506120600877003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liepnieks JJ, Zhang LQ, Benson MD. Progression of transthyretin amyloid neuropathy after liver transplantation. Neurology. 2010 Jul 27;75(4):324–327. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ea15d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yazaki M, Liepnieks JJ, Kincaid JC, Benson MD. Contribution of wild-type transthyretin to hereditary peripheral nerve amyloid. Muscle Nerve. 2003 Oct;28(4):438–442. doi: 10.1002/mus.10452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yazaki M, Mitsuhashi S, Tokuda T, et al. Progressive wild-type transthyretin deposition after liver transplantation preferentially occurs onto myocardium in FAP patients. Am J Transplant. 2007 Jan;7(1):235–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng B, Connors LH, Davidoff R, Skinner M, Falk RH. Senile systemic amyloidosis presenting with heart failure: a comparison with light chain-associated amyloidosis. Archives of internal medicine. 2005 Jun 27;165(12):1425–1429. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagerstedt JO, Budamagunta MS, Oda MN, Voss JC. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy of site-directed spin labels reveals the structural heterogeneity in the N-terminal domain of apoA-I in solution. J Biol Chem. 2007 Mar 23;282(12):9143–9149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong YQ, Binger KJ, Howlett GJ, Griffin MD. Methionine oxidation induces amyloid fibril formation by full-length apolipoprotein A-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Feb 2;107(5):1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910136107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mucchiano GI, Jonasson L, Haggqvist B, Einarsson E, Westermark P. Apolipoprotein A-I-derived amyloid in atherosclerosis. Its association with plasma levels of apolipoprotein A-I and cholesterol. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001 Feb;115(2):298–303. doi: 10.1309/PJE6-X9E5-LX6K-NELY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westermark P, Mucchiano G, Marthin T, Johnson KH, Sletten K. Apolipoprotein A1-derived amyloid in human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. The American journal of pathology. 1995 Nov;147(5):1186–1192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roertgen KE, Lund EM, O’Brien TD, Westermark P, Hayden DW, Johnson KH. Apolipoprotein AI-derived pulmonary vascular amyloid in aged dogs. The American journal of pathology. 1995 Nov;147(5):1311–1317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon A, Murphy CL, Kestler D, et al. Amyloid contained in the knee joint meniscus is formed from apolipoprotein A-I. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Nov;54(11):3545–3550. doi: 10.1002/art.22201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krebs MR, Macphee CE, Miller AF, Dunlop IE, Dobson CM, Donald AM. The formation of spherulites by amyloid fibrils of bovine insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Oct 5;101(40):14420–14424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405933101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin LW, Claborn KA, Kurimoto M, et al. Imaging linear birefringence and dichroism in cerebral amyloid pathologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Dec 23;100(26):15294–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534647100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Argiles A, Garcia Garcia M, Mourad G. Phagocytosis of dialysis-related amyloid deposits by macrophages. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2002 Jun;17(6):1136–1138. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.6.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommer C, Schroder JM. Amyloid neuropathy: immunocytochemical localization of intra- and extracellular immunoglobulin light chains. Acta neuropathologica. 1989;79(2):190–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00294378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vital A, Vital C. Amyloid neuropathy: relationship between amyloid fibrils and macrophages. Ultrastructural pathology. 1984;7(1):21–24. doi: 10.3109/01913128409141850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acebo E, Mayorga M, Fernando Val-Bernal J. Primary amyloid tumor (amyloidoma) of the jejunum with spheroid type of amyloid. Pathology. 1999 Feb;31(1):8–11. doi: 10.1080/003130299105449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gertz MA, Buadi FK, Hayman SR. Treatment of immunoglobulin light chain (primary or AL) amyloidosis. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011 Jun;25(7):620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bodin K, Ellmerich S, Kahan MC, et al. Antibodies to human serum amyloid P component eliminate visceral amyloid deposits. Nature. 2010 Nov 4;468(7320):93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature09494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berk JL, Dyck PJ, Obici L, et al. The diflunisal trial: update on study drug tolerance and disease progression. Amyloid. 2011 Jun;18(Suppl 1):191–192. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.574354073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]