Background: Two-pore channel 2 (TPC2) is a calcium channel, but its function in osteoclasts is unknown.

Results: TPC2 expression levels in osteoclast precursor cells were increased upon osteoclast differentiation induced by RANKL. Down-regulation of TPC2 expression suppressed RANKL-induced intracellular Ca2+ signaling as well as nuclear localization of NFATc1 and inhibited osteoclastogenesis.

Conclusion: TPC2 regulates osteoclastogenesis.

Significance: TPC2 plays a critical role in osteoclast differentiation.

Keywords: Bone, Calcium, Ion Channels, Osteoclast, Osteoporosis

Abstract

Osteoclast differentiation is one of the critical steps that control bone mass levels in osteoporosis, but the molecules involved in osteoclastogenesis are still incompletely understood. Here, we show that two-pore channel 2 (TPC2) is expressed in osteoclast precursor cells, and its knockdown (TPC2-KD) in these cells suppressed RANKL-induced key events including multinucleation, enhancement of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activities, and TRAP mRNA expression levels. With respect to intracellular signaling, TPC2-KD reduced the levels of the RANKL-induced dynamic waving of Ca2+ in RAW cells. The search for the target of TPC2 identified that nuclear localization of NFATc1 is retarded in TPC2-KD cells. Finally, TPC2-KD suppressed osteoclastic pit formation in cultures. We conclude that TPC2 is a novel critical molecule for osteoclastogenesis.

Introduction

Bone mass is regulated by remodeling, which is a delicate balance between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic bone resorption. Negative balance in bone remodeling reduces bone mass and causes osteopenic skeletal disorders such as osteoporosis (1, 2). Defects in the control of osteoclast differentiation and activity are the primary causes of skeletal diseases (1, 3). Osteoclasts are derived from hematopoietic precursors that undergo multiple differentiation steps shared with those in monocyte-macrophage lineage (1, 3). The monocyte-osteoclast precursors differentiate based on the RANK/RANKL3 signaling pathway into committed preosteoclasts (4). RANK cooperates with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) adaptors to activate phospholipase Cγ, which promotes the release of intracellular Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (5).

Changes in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) control multiple cellular functions. The importance of [Ca2+]i) in osteoclast differentiation has been reported (6–9). The RANK/RANKL pathway evokes Ca2+ oscillation leading to calcium-calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation and activation of NFATc1 which translocates to nucleus from cytosol (6). Intracellular Ca2+ dynamics are considered to result from repetitive release of Ca2+ from ER (7). In osteoclasts, the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) type 2 is essential for the changes of [Ca2+]i and differentiation (8). The osteoclastic Ca2+ oscillations originate from intracellular Ca2+ stores because Ca2+ oscillation persists in Ca2+-free extracellular solution (9, 10). However, the molecules involved in calcium signaling in osteoclastic differentiation are still incompletely understood. TPC2 is a recently identified novel family of Ca2+-permeable channels and activated by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), a potent Ca2+-mobilizing messenger (11, 12). TPC2 is a specific lysosomal calcium channel that does not localize in endosome, ER, Golgi, and mitochondria (12). Two isoforms, TPC1 and TPC2, have been cloned as translation products of different genes in mammals, and TPC1 localizes predominantly in endosomes (12, 13). NAADP evokes Ca2+ release via TPC2. This often leads to recruitment of further Ca2+ release from the ER through IP3Rs or ryanodine receptors (12, 13). TPC2 is required for myocyte differentiation (14, 15). This channel is also involved in autophagy in astrocytes (16). Considering bone physiology, osteoclasts are regulated by calcium signaling (17). However, the presence and role of TPC2 in osteoclasts remain unknown. Thus, we examined TPC2 channel in osteoclasts.

Here we show that TPC2 is expressed in osteoclasts and is a regulator for osteoclast differentiation. The expression levels of TPC2 are critical for osteoclastogenesis. Furthermore, TPC2 regulates [Ca2+]i and NFATc1 activity in osteoclastic precursors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Mouse bone marrow cells were obtained from the tibia and femur of mice (C57BL/6, 4-week-old males; Charles River). Bone marrow stromal cells were depleted from mouse bone marrow macrophage (BMM) cells using the Sephadex G-10 (GE Healthcare) column as described previously (18–20). They were cultured in α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (PS) with 20 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; R&D Systems). A mouse monocyte/macrophage cell line, RAW264.7 (ATCC) was cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. The RAW cell has been also used widely as a preosteoclast cell line in many previous reports (21–23). All cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

Establishment of TPC2 Knockdown Cell Lines

Lentiviral constructs expressing two different artificial micro-RNAs targeting murine TPC2 (TPC2-miR-A and B) and a negative control plasmid were purchased from Invitrogen (pLenti6.3/V5-DEST and BLOCK-iT Pol II miR RNAi Expression Vector which express artificial micro-RNAs). Target sequences were as follows: A, 5′-tcatctttagccaccactact-3′; B, 5′-gataggaagcttgtttctgat-3′. According to the manufacturer's protocol, lentiviral vectors and three packaging plasmids (pVSVG, pLG1, and pLG2) were transfected into 293FT cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty h after transfection, the culture medium was collected as lentiviral solution. Viral titers were estimated using a Lenti-X quantitative RT-PCR (Chemicon). Viral transduction of RAW cells was performed by addition of lentiviral solution into the medium in the presence of 6 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma). Stably transduced cells were selected with 5 μg/ml blasticidin (Invitrogen).

Osteoclast Development

For osteoclast differentiation, clonal RAW cell lines were seeded at 2.0 × 105 cell/cm2 in α-MEM with sRANKL (50 ng/ml; ORIENTAL YEAST). Viral transformation of BMM cells was performed by the addition of lentiviral solution into medium in the presence of 6 μg/ml Polybrene and 20 ng/ml M-CSF for 12 h. The BMMs were subsequently cultured in the presence of 5 μg/ml blasticidin and 20 ng/ml M-CSF for 3 days. These selected cells were cultured in the presence of 20 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml sRANKL to induce osteoclast differentiation. For counting the number of osteoclasts, TRAP staining was performed as described previously (19). The TRAP-positive cell, which has >3 nuclei, was defined as multinucleated osteoclast. This experiment was repeated on three separate occasions.

Measurement of TRAP Activity

To measure TRAP activity, cells were lysed in extraction buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, 1% Nonidet P-40, pH 8.0) supplemented with protease inhibitor (Sigma). An aliquot of 20 μl of lysate was added to 200 μl of TRAP buffer (50 mm sodium acetate, 25 mm sodium tartrate, pH 5.0, 0.4 mm MnCl2,0.4% N,N-dimethylformamide, 0.2 mg/ml Fast Red Violet, 0.5 mg/ml naphthol AS-MX phosphate). After incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader (SPECTRAmax; Molecular Devices). The data were normalized against total protein, which was determined by BCA kit (Pierce). Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Osteoclast Pit Assay

In experiments of resorption activity, clonal RAW cell lines and viral transformation of BMMs were seeded on a calcium-phosphate thin layer coated dishes (OSTEOLOGIC; BD Biosciences). After 5 (RAW) or 7 (BMMs) days of culture, osteoclasts were detached by 5% sodium hypochloride. The resorption pit was measured by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). This experiment was repeated twice.

Gene Expression Assay

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First-strand cDNA was produced from total RNA using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed based on Step One Real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green and specific forward and reverse primers. Transcripts were normalized against the levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcripts. Primer sequences were as follows: TPC2 forward, 5′-gaagcacaggaccaggagag-3′ and reverse, 5′-aaaggcccggttctgagtat3′; TRAP forward, 5′-gaccaccttggcaatgtctctg-3′ and reverse, 5′-tggctgaggaagtcatctgagtttg-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-agaaggtggtgaagcaggcat-3′ and reverse, 5′-cgaaggtggaagagtgggagttg-3′; calcitonin receptor forward, 5′-gccagccgcccaagactctg-3′ and reverse, 5′-ggcagggtgaggcgcagaag-3′; integrin β3 forward, 5′-agtgctctgaggaggattaccg-3′ and reverse, 5′-tgccgaagtcgctgctatgg-3′; cathepsin K forward, 5′-ttctcctctcgttggtgctt-3′ and reverse, 5′-aaaaatgccctgttgtgtcc-3′.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously (24). Briefly, control and TPC2 knockdown cells cultured on type I collagen-coated 3.5-cm glass-bottom dishes or 3.5-cm plastic dishes with RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 3 days were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100, and after blocking with 1% BSA and 5% normal goat serum, were incubated with anti-NFATc1 (1:500, mAb 7A6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies (1:500; Invitrogen). Nuclei were visualized by DAPI (Invitrogen) staining. Images were obtained by CCD camera (Biozero; Keyence) and analyzed for quantification of nuclear location of NFATc1. At least 300–350 mononuclear cells were counted in 5 regions/dish. Three dishes were analyzed in control and knockdown conditions.

Western Blotting

Cells were rinsed with cold PBS and then extracted cytoplasm and nuclear protein by DUALXtract (Dualsytems Biotech). Western blotting (WB) was performed as described previously (24). Briefly, SDS-PAGE was performed using any kDa gels (Bio-Rad) to separate proteins which were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PVDF). Blots were blocked with Ezblock (Atto) and then incubated with antibodies (NFATc1; 1:1000, mAb 7A6, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; histone H1; 1:1000, mAb AE4, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; β-actin, 1:5000, mAb AC74, Sigma). The images were captured by CCD camera (LAS-3000; Fuji-film), and then the quantitative analysis was performed by Multigage (Fuji-film).

Intracellular Ca2+ Imaging and Analysis

To examine the effects of RANKL (1 nm) on the intracellular Ca2+ level, cells were analyzed as follows. RAW-derived control and TPC2-KD cell lines and stromal cell-free bone marrow cells expressing micro-RNA (negative control and TPC2 target sequence B) were subjected to intracellular Ca2+ imaging. Cells were loaded with 4 μm Fluo-4/AM (Dojindo; excitation 488 nm, emission 505–530 nm) for 30 min in physiological solution containing 145 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm d-glucose, 0.1% BSA, and 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4). After rinsing with physiological solution, the fluorescent images were captured every 6 s for 15 min using confocal fluorescent microscope (LSM5 PASCAL; Carl Zeiss). To analyze [Ca2+]i changes in individual cells in these experiments, fluorescent intensity in each cell was quantified using LSM image software (Carl Zeiss). Approximately 20–30 cells/field were analyzed in a single culture, and the experiment was repeated several times to obtain 300–400 data points from experimental groups of RAW cells, and 60–80 cells from the groups of BMMs. These experiments were started after incubating physiological solution at room temperature for 5 min. At the end of experiments, 5 μm ionomycin (Sigma) was added to confirm cell viability. To analyze the effect of depletion in ER or lysosomal Ca2+ store, cells were preincubated with thapsigargin (1 μm; Sigma) and/or bafilomycin A1 (100 nm; Sigma) for 40 min (12).

To analyze the serial changes of fluorescent intensity of each cell, a chronological data set obtained from every single cell was mathematically fitted to an exponential curve using OriginPro 8.5 (OriginLab), and then the value named as “peak curve area” was calculated by a command named “Peak Analyzer.” At the beginning of each experiment, the value of fluorescence intensity was defined as 1.0. The peak curve area represents the integrated extent of peak fluctuation during 15 min and can be utilized as an index of Ca2+ oscillation.

To compare the distribution of peak curve areas in the control and knockdown cells statistically, the histograms (for peak curve area) were drawn for each of the independent 15 experiments in control and knockdown in RAW-derived cell lines and each of the independent four experiments in BMMs. Total cell numbers used for measurement were 361 (control) and 323 (knockdown) in RAW, and 79 (control) and 67 (knockdown) in BMM, respectively. The threshold was determined at the second turning point of the fitted polynomial curve for the distribution (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). The cells were defined as responding cells when the values of the peak curve area were larger than the thresholds. The percentage of responding cells in each experimental group were compared between the control and knockdown.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed based on Student's t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Bonferroni test was applied as a post hoc test.

RESULTS

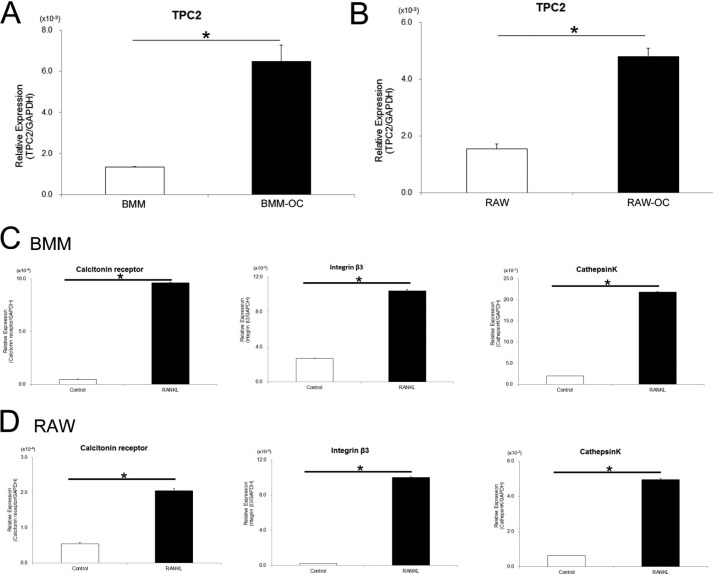

TPC2 expression was detected in BMMs at base-line levels (Fig. 1A, BMM). Induction of these cells to differentiate into osteoclasts significantly enhanced the expression of TPC2 (Fig. 1A, BMM-OC). Base-line TPC2 expression was also detected in osteoclast precursor-like RAW cells, and again induction of differentiation into mature osteoclasts significantly enhanced TPC2 expression levels (Fig. 1B, RAW-OC). For the confirmation of the differentiation of BMMs and RAW cells, we examined the expression of genes. The BMM and RAW cells were differentiated into osteoclasts upon RANKL treatment as these cells expressed mRNAs of genes encoding the terminal osteoclast markers including calcitonin receptor, integrin β3, and cathepsin K (Fig. 1, C and D).

FIGURE 1.

TPC2 expression levels correlate with the levels of in vitro osteoclastogenesis. A and B, increase in TPC2 mRNA expression during RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. The mRNA expression levels of TPC2 were analyzed based on quantitative RT-PCR in BMM (A) and RAW (B) cells. BMM-OC, BMM-derived matured osteoclast (day 5 of RANKL treatment). RAW-OC, RAW-derived matured osteoclast (day 3 of RANKL treatment). *, p < 0.01 (n = 3). C and D, mRNA expression of osteoclast terminal differentiation markers (calcitonin receptor, integrin β3, and cathepsin K) in BMM (C) (day 5) and RAW cell (D) (day 3). *, p < 0.01 (n = 3).

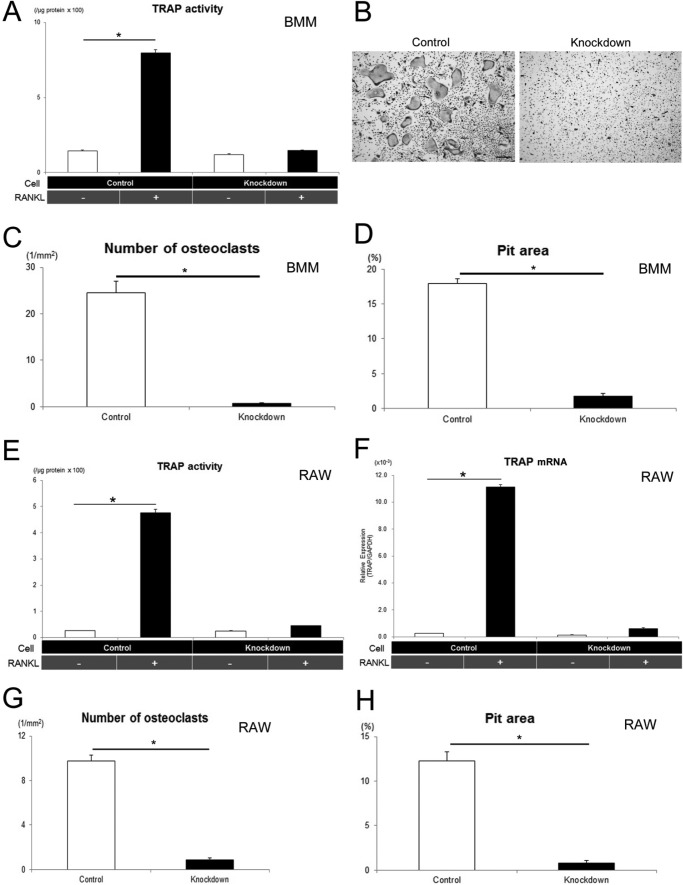

To address further the functional role of TPC2 in osteoclast differentiation, we knocked down TPC2 in preosteoclasts by using lentivirus. The expression levels of TPC2 in BMM and RAW cell lines were reduced by approximately 80% compared with control (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). As control cells, we transfected negative control miRNA by lentivirus system. Quantification of TRAP activity, which is an index of osteoclastogenesis, indicated that RANKL treatment increased TRAP activity in control cells (Fig. 2A, second bar from the left) compared with base line (Fig. 2A, leftmost bar) in BMMs. In contrast, TPC2 knockdown suppressed RANKL-induced TRAP activity in BMMs (Fig. 2A, right two bars). The similar results were obtained in TPC2-KD RAW cell lines (Fig. 2E, Knockdown). With regard to gene expression, TRAP mRNA expression was increased significantly after RANKL treatment in control, and this TRAP mRNA expression was significantly suppressed by knockdown of TPC2 (Fig. 2F). Morphological examination revealed that RANKL treatment induced development of TRAP(+)-multinucleated cells during osteoclastogenesis in control BMM and RAW cells (Fig. 2B (BMM) and supplemental Fig. S1C (RAW), left panel, Control). In contrast, TPC2 knockdown suppressed RANKL-induced formation of TRAP(+)-multinucleated cells (Fig. 2B (BMM), and supplemental Fig. S1C (RAW), right panel, Knockdown). TPC2 knockdown also reduced the number of osteoclasts (Fig. 2, C (BMM) and G (RAW)). RANKL-induced resorption activity was evaluated based on pit formation assay. Pit formation activity was increased by RANKL treatment, but this was reduced in TPC2 knockdown in BMM cells (Fig. 2D). Similarly, TPC2 knockdown also reduced RANKL-induced pit formation activity in RAW cell lines (Fig. 2H). The TPC2 knockdown also suppressed the increase in TRAP activity, osteoclast number, and resorption activity during osteoclast differentiation in RAW cells when independent miR sequence was used to knockdown TPC2 (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

TPC2 regulates in vitro osteoclastogenesis and resorption activity. A, TRAP activities in BMM cultured in the presence or absence of RANKL for 5 days. *, p < 0.01 (n = 5). B, TRAP staining of osteoclasts developed in the cultures of BMM cells on day 5 of RANKL treatment. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, number of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells at 5 days in culture of BMM. *, p < 0.01 (n = 5). D, pit formation assay of control and TPC2-KD BMM cells. Resorbed area against total area is expressed as percentage. *, p < 0.01 (n = 4). E, TRAP activities in RAW cell lines cultured in the presence or absence of RANKL for 3 days. *, p < 0.01 (n = 5). F, TRAP mRNA expression in RAW cell lines on day 2 of RANKL treatment. *, p < 0.01 (n = 3). G, number of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells at 3 days in culture of RAW cell lines. *, p < 0.01 (n = 5). H, pit formation assay of control and TPC2-KD RAW cell lines. Resorbed area against total area is expressed as percentage. *, p < 0.01 (n = 4).

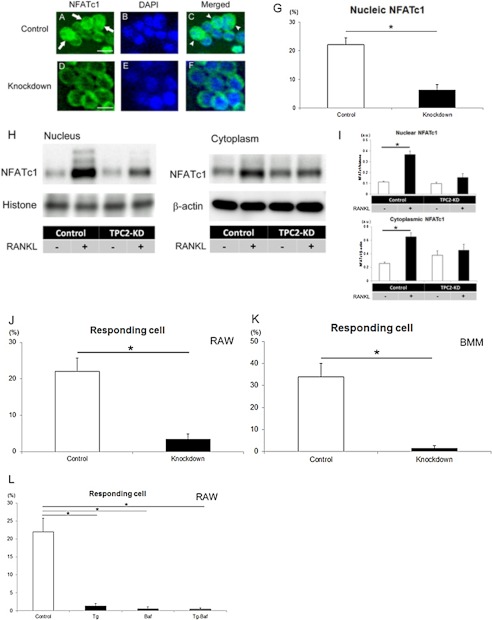

To address roles of TPC2 action in regulation of signaling associated with osteoclast differentiation, we examined the effects of TPC2 knockdown on nuclear localization of NFATc1 because TPC2 regulates [Ca2+]i (12, 13) that is critical for osteoclastogenesis based on nuclear translocation of NFATc1. To this end, subcellular localization of NFATc1 was examined using an antibody against NFATc1 after RANKL treatment. In the early stages of osteoclast development, some mononuclear cells are known to be positive to for TRAP activities (1, 3). In such mononuclear cells, immunocytochemistry showed that NFATc1 was localized in both cytosol and nuclei in the cells (Fig. 3A, green, arrows). This was shown by the locations of nuclear DNA based on DAPI staining (Fig. 3B, blue) and by merging the two signals (Fig. 3C; green signal was seen both inside and outside the nuclei, arrowheads). TPC2 knockdown suppressed nuclear localization of NFATc1 in nuclei (Fig. 3D), and this was supported when nuclear DAPI staining (Fig. 3E, blue) was merged with NFATc1 (Fig. 3F). Quantification of the number of cells having NFATc1 in nuclei revealed that TPC2 knockdown suppressed the level of nuclear NFATc1 by >70% (Fig. 3G, 22% versus 6% for control and TPC2-KD, respectively). These results indicate that the presence of TPC2 promotes nuclear localization of NFATc1. To examine further NFATc1 localization biochemically, Western blot analyses was performed by using nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions of RAW cells (Fig. 3, H and I). The results showed that RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation increased both nuclear and cytoplasmic NFATc1 protein in control-RAW cells in accordance with previous reports (5, 6, 25). In contrast, TPC2-KD suppressed such RANKL-induced increase in NFATc1 protein levels in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 3, H and I). This observation supports our results that TPC2 regulates osteoclastogenesis via NFATc1 signaling.

FIGURE 3.

TPC2 regulates nuclear localization of NFATc1 and dynamic response of intracellular Ca2+. A–F, localization of NFATc1 in control (A–C) and TPC2 knockdown B (D–F) mononucleated cells 3 days after treatment with RANKL. White arrows (A) and arrowheads (C) indicate nuclear NFATc1 in control. Green, NFATc1; blue, DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. G, percentage of nucleic NFATc1 in a control and TPC2 knockdown cells. *, p < 0.01 (n = 3). H and I, quantification of NFATc1 protein levels in nucleus and cytoplasm based on Western blot analysis. H, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of cell extracts prepared from control and TPC2-KD RAW cells. I, analysis of NFATc1 protein levels normalized against histone (nuclear) and β-actin (cytoplasm). *, p < 0.01 (n = 3). J, percentage of responding cells. The cells were defined as responsive cells when the values of the peak curve area were larger than the thresholds (see supplemental Fig. S2, A and B), as described under “Experimental Procedures”) in mononuclear RAW cells (control and knockdown; day 3 after treatment with RANKL at 1 nm). *, p < 0.01 (n = 15). K, percentage of responding cells in mononuclear BMM cells (day 3 after treatment with RANKL).*, p < 0.01 (n = 4). L, percentage of responding cells (see the definition of responding cells under “Experimental Procedures, Intracellular Ca2+ Imaging and Analysis”). Cells were treated with RANKL in the presence of Tg (1 μm), Baf (100 nm) or both (Tg-Baf) or vehicle (Control). *, p < 0.01 (n = 10–25).

Finally, we analyzed the function of TPC2 in the osteoclast precursor RAW cells regarding [Ca2+]i levels. Because TPC2 is a Ca2+ channel, the dynamic responses of the intracellular Ca2+ level were investigated (representative Ca2+ plots, supplemental Fig. S2C). In control RAW cells, ∼20% of the cells were showing [Ca2+]i dynamic response upon RANKL treatment. In contrast, TPC2 knockdown in these cells suppressed [Ca2+]i dynamic response to RANKL by >70% (Fig. 3J, 22% versus 5% for control and TPC2-KD, respectively). Responding cells did not appear when RANKL was not added (supplemental Fig. S2C). BMMs were also examined, and >30% of control cells exhibited [Ca2+]i dynamic response to RANKL. Again, in contrast to control, TPC2 knockdown suppressed the levels of cells positive for the [Ca2+]i dynamic response significantly (Fig. 3K, 34% versus 2% for control and TPC2-KD, respectively).

To examine lysosome-dependent [Ca2+]i levels, bafilomycin A1 (Baf) was used to deplete lysosomal but not ER-Ca2+ store (12). These cells were subjected to examination of [Ca2+]i in response to RANKL. Baf reduced the levels of responding cells (Fig. 3L). Such Baf-induced reduction in the levels of responding cells was similar to that in the cells treated with thapsigargin (Tg), which depletes ER store but not lysosomal Ca2+ store (Fig. 3L). No additive effects of these two inhibitors were observed (Fig. 3L, Tg-Baf). These results indicate that Ca2+ release from lysosomal store is a key event in the RANKL-induced [Ca2+]i dynamic response.

In TPC2 knockdown RAW cells, the responding cells were not observed in cells with Tg, Baf, and both (data not shown). We further analyzed RANKL-induced [Ca2+]i levels and quantified peak curve area in more than 800 control-RAW cells as well as cells treated with Baf or Tg or both (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). Baf treatment caused a peak shift of the Gaussian curve (of the responding cell number upon RANKL treatment) to the left compared with Tg treatment (supplemental Fig. S3A, Tg-Baf, arrow). The averaged peak curve area was also reduced by Tg-Baf treatment compared with Tg alone or Baf alone (supplemental Fig. S3B). These results support the notion that lysosomal-dependent [Ca2+]i exists independent of the ER store in RANKL-treated osteoclast precursors.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that Ca2+ channel TPC2 plays a key role in osteoclast differentiation. This was associated with the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling and NFATc1 translocation in the precursor cells. Osteoclast differentiation is driven by several important events, and one of these is mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ stores (1, 3). The Ca2+ release from the ER through IP3Rs has been reported (8), but not much was known about Ca2+ release due to lysosomal store. Our results provide the first evidence that the Ca2+ release in osteoclast precursors via TPC2 is a trigger for a subsequent larger globalized Ca2+ release from ER through IP3Rs. Our identification of TPC2 adds a novel contributor for osteoclastogenesis and Ca2+ signaling. In this study, we do not exclude the possibility that Ca2+ from other organelles may affect RANKL-induced [Ca2+]i. TPC2 knockdown suppressed osteoclast differentiation of the precursor cells subjected to RANKL stimulation. Nuclear transfer of NFATc1 was also suppressed in these cells. Thus, these effects were TPC2-dependent. We showed that TPC2 is critical for osteoclast differentiation from the precursor cells. The early step of osteoclast differentiation has been considered as one of the targets of osteoporosis treatment. In fact, the anti-RANKL antibody, denosumab, has been reported to efficiently improve fracture rate (26). TPC2-KD suppressed RANKL action to promote osteoclast differentiation. Thus, our data indicate that TPC2 is a downstream effector for RANKL and that it could be one of the targets of denosumab in the treatment of osteoporosis.

The expression levels of TPC2 were enhanced during osteoclast differentiation. Although the mechanism of how TPC2 expression increases during osteoclast differentiation remains to be determined, our current findings indicate that TPC2 could be a differentiation indicator of osteoclastic cells. The lysosome levels in matured osteoclasts are higher than in mononucleated cells (1, 27). Higher TPC2 expression in mature osteoclasts might be dependent on the increase in lysosome number. In fact, expression levels of TPC2 in osteoclasts were higher than many other tissue and cells (brain, spleen, skeletal muscle; data not shown). It would be of interest whether TPC2 expression could be monitored as a biomarker of osteoclastic activity in pathological conditions.

How TPC2 knockdown inhibits NFATc1 nuclear localization during RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis is of interest. We assume that the calcium-calcineurin pathway may be affected in TPC2-knockdown cells. Steady-state [Ca2+]i in these cells after exposure to RANKL may be altered. The [Ca2+]i is elevated before generation of Ca2+ oscillation (13, 28, 29). Also, it was reported that the Ca2+ release from ER through IP3Rs or ryanodine receptors is a main pathway for inducing Ca2+ oscillation and is promoted by NAADP-induced Ca2+ release from lysosomes (8, 12, 13). Therefore, we speculate that TPC2 is involved in the mechanisms inducing Ca2+ oscillation by affecting [Ca2+]i that may stimulate upstream IP3Rs-Ca2+ signaling. It is still to be determined whether the Ca2+ oscillation is related to the TPC2-induced dynamic response of [Ca2+]i. Nevertheless, our observation revealed a new possibility for the TPC2 regulation of [Ca2+]i (8, 12, 13, 28).

We showed the role of TPC2 in osteoclasts. Osteoclasts express general radical molecules including NADP/NADPH (30, 31). Thus, a part of NADP would be transformed into NAADP by ADP-ribosyl cyclases including CD38 (32). The deficiency of CD38 promotes osteoclastogenesis, resulting in decreased bone mass (33). This seems contradictory to NAADP synthesis. However, it has been reported that CD38 acts as a NAADP-degrading enzyme in vivo (34). It remains to be elucidated whether TPC2 also plays a role in mature osteoclasts. Considering high TPC2 expression in the mature osteoclasts (Fig. 1), TPC2 may play a certain role via lysosomal Ca2+ release in mature osteoclast activity. In fact, the significance of lysosome has been reported in the mature osteoclasts (17, 27, 35, 36).

In summary, our results demonstrate the role of the calcium channel, TPC2, in osteoclasts. TPC2 regulates RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. TPC2 induces intracellular Ca2+ dynamic response in osteoclast progenitor cells. Our findings suggest that the osteoclastic TPC2 function may be a target to develop novel therapeutic agents for skeletal disorders.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Uehara Memorial Foundation, Nakatomi Foundation, and Mochida Memorial Foundation.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- RANK

- receptor activator of NF-κB

- Baf

- bafilomycin A1

- BMM

- bone marrow macrophage

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- IP3R

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- KD

- knockdown

- NAADP

- nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- RANKL

- RANK ligand

- Tg

- thapsigargin

- TPC2

- two-pore channel 2

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boyle W. J., Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L. (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karsenty G., Wagner E. F. (2002) Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Dev. Cell 2, 389–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teitelbaum S. L., Ross F. P. (2003) Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 638–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lacey D. L., Timms E., Tan H. L., Kelley M. J., Dunstan C. R., Burgess T., Elliott R., Colombero A., Elliott G., Scully S., Hsu H., Sullivan J., Hawkins N., Davy E., Capparelli C., Eli A., Qian Y. X., Kaufman S., Sarosi I., Shalhoub V., Senaldi G., Guo J., Delaney J., Boyle W. J. (1998) Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93, 165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koga T., Inui M., Inoue K., Kim S., Suematsu A., Kobayashi E., Iwata T., Ohnishi H., Matozaki T., Kodama T., Taniguchi T., Takayanagi H., Takai T. (2004) Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature 428, 758–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takayanagi H., Kim S., Koga T., Nishina H., Isshiki M., Yoshida H., Saiura A., Isobe M., Yokochi T., Inoue J., Wagner E. F., Mak T. W., Kodama T., Taniguchi T. (2002) Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev. Cell 3, 889–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verkhratsky A. (2005) Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium store in the endoplasmic reticulum of neurons. Physiol. Rev. 85, 201–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuroda Y., Hisatsune C., Nakamura T., Matsuo K., Mikoshiba K. (2008) Osteoblasts induce Ca2+ oscillation-independent NFATc1 activation during osteoclastogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8643–8648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Masuyama R., Vriens J., Voets T., Karashima Y., Owsianik G., Vennekens R., Lieben L., Torrekens S., Moermans K., Vanden Bosch A., Bouillon R., Nilius B., Carmeliet G. (2008) TRPV4-mediated calcium influx regulates terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Cell Metab. 8, 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu M. X., Ma J., Parrington J., Galione A., Evans A. M. (2010) TPCs: endolysosomal channels for Ca2+ mobilization from acidic organelles triggered by NAADP. FEBS Lett. 584, 1966–1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee H. C., Aarhus R. (1995) A derivative of NADP mobilizes calcium stores insensitive to inositol trisphosphate and cyclic ADP-ribose. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2152–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calcraft P. J., Ruas M., Pan Z., Cheng X., Arredouani A., Hao X., Tang J., Rietdorf K., Teboul L., Chuang K. T., Lin P., Xiao R., Wang C., Zhu Y., Lin Y., Wyatt C. N., Parrington J., Ma J., Evans A. M., Galione A., Zhu M. X. (2009) NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature 459, 596–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galione A., Morgan A. J., Arredouani A., Davis L. C., Rietdorf K., Ruas M., Parrington J. (2010) NAADP as an intracellular messenger regulating lysosomal calcium-release channels. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1424–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tugba Durlu-Kandilci N., Ruas M., Chuang K. T., Brading A., Parrington J., Galione A. (2010) TPC2 proteins mediate nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)- and agonist-evoked contractions of smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24925–24932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aley P. K., Mikolajczyk A. M., Munz B., Churchill G. C., Galione A., Berger F. (2010) Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate regulates skeletal muscle differentiation via action at two-pore channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19927–19932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pereira G. J., Hirata H., Fimia G. M., do Carmo L. G., Bincoletto C., Han S. W., Stilhano R. S., Ureshino R. P., Bloor-Young D., Churchill G., Piacentini M., Patel S., Smaili S. S. (2011) Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) regulates autophagy in cultured astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27875–27881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coxon F. P., Taylor A. (2008) Vesicular trafficking in osteoclasts. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 424–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kukita A., Kukita T., Shin J. H., Kohashi O. (1993) Induction of mononuclear precursor cells with osteoclastic phenotypes in a rat bone marrow culture system depleted of stromal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196, 1383–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mori H., Sakai H., Morihata H., Kawawaki J., Amano H., Yamano T., Kuno M. (2003) Regulatory mechanisms and physiological relevance of a voltage-gated H+ channel in murine osteoclasts: phorbol myristate acetate induces cell acidosis and the channel activation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 2069–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ly I. A., Mishell R. I. (1974) Separation of mouse spleen cells by passage through columns of Sephadex G-10. J. Immunol. Methods 5, 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schröder H. C., Wang X. H., Wiens M., Diehl-Seifert B., Kropf K., Schlossmacher U., Müller W. E. (2012) Silicate modulates the cross-talk between osteoblasts (SaOS-2) and osteoclasts (RAW 264.7 cells): inhibition of osteoclast growth and differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 113, 3197–3206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takito J., Nakamura M., Yoda M., Tohmonda T., Uchikawa S., Horiuchi K., Toyama Y., Chiba K. (2012) The transient appearance of zipper-like actin superstructures during the fusion of osteoclasts. J. Cell Sci. 125, 662–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pham L., Kaiser B., Romsa A., Schwarz T., Gopalakrishnan R., Jensen E. D., Mansky K. C. (2011) HDAC3 and HDAC7 have opposite effects on osteoclast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12056–12065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Notomi T., Shigemoto R. (2004) Immunohistochemical localization of Ih channel subunits, HCN1–4, in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 471, 241–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Youn M. Y., Takada I., Imai Y., Yasuda H., Kato S. (2010) Transcriptionally active nuclei are selective in mature multinucleated osteoclasts. Genes Cells 15, 1025–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McClung M., Boonen S., Torring O., Roux C., Rizzoli R., Bone H., Benhamou C. L., Lems W., Minisola S., Halse J., Hoeck H., Eastell R., Wang A., Siddhanti S., Cummings S. (October 4, 2011) Effect of denosumab treatment on the risk of fractures in subgroups of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 10.1002/jbmr.536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nyman J. K., Väänänen H. K. (2010) A rationale for osteoclast selectivity of inhibiting the lysosomal V-ATPase a3 isoform. Calcif. Tissue Int. 87, 273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verkhratsky A., Petersen O. H. (2002) The endoplasmic reticulum as an integrating signalling organelle: from neuronal signalling to neuronal death. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 447, 141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berridge M. J., Lipp P., Bootman M. D. (2000) The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Silverton S. (1994) Osteoclast radicals. J. Cell. Biochem. 56, 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Razzouk S., Lieberherr M., Cournot G. (1999) Rac-GTPase, osteoclast cytoskeleton and bone resorption. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 78, 249–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aarhus R., Graeff R. M., Dickey D. M., Walseth T. F., Lee H. C. (1995) ADP-ribosyl cyclase and CD38 catalyze the synthesis of a calcium-mobilizing metabolite from NADP. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30327–30333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun L., Iqbal J., Dolgilevich S., Yuen T., Wu X. B., Moonga B. S., Adebanjo O. A., Bevis P. J., Lund F., Huang C. L., Blair H. C., Abe E., Zaidi M. (2003) Disordered osteoclast formation and function in a CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase)-deficient mouse establishes an essential role for CD38 in bone resorption. FASEB J. 17, 369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmid F., Bruhn S., Weber K., Mittrücker H. W., Guse A. H. (2011) CD38: a NAADP degrading enzyme. FEBS Lett. 585, 3544–3548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weinert S., Jabs S., Supanchart C., Schweizer M., Gimber N., Richter M., Rademann J., Stauber T., Kornak U., Jentsch T. J. (2010) Lysosomal pathology and osteopetrosis upon loss of H+-driven lysosomal Cl− accumulation. Science 328, 1401–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Henriksen K., Sørensen M. G., Jensen V. K., Dziegiel M. H., Nosjean O., Karsdal M. A. (2008) Ion transporters involved in acidification of the resorption lacuna in osteoclasts. Calcif. Tissue Int. 83, 230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.