Background: IL-32α is known to interact with FAK1, and IL-32α overexpression in chronic myeloid leukemia cells increases natural killer cell-mediated killing.

Results: IL-32α interacted with PKCϵ and STAT3, mediated STAT3 phosphorylation, and thereby augmented IL-6 production.

Conclusion: IL-32α elevated IL-6 production through interaction with PKCϵ and STAT3.

Significance: The interaction of IL-32α with PKCϵ and STAT3 reveals a new intracellular mediatory role of IL-32α.

Keywords: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), Gene Regulation, Immunochemistry, Interleukin, STAT3, Interleukin-32α, Interleukin-6, PKCϵ, THP-1

Abstract

IL-32α is known as a proinflammatory cytokine. However, several evidences implying its action in cells have been recently reported. In this study, we present for the first time that IL-32α plays an intracellular mediatory role in IL-6 production using constitutive expression systems for IL-32α in THP-1 cells. We show that phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-induced increase in IL-6 production by IL-32α-expressing cells was higher than that by empty vector-expressing cells and that this increase occurred in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Treatment with MAPK inhibitors did not diminish this effect of IL-32α, and NF-κB signaling activity was similar in the two cell lines. Because the augmenting effect of IL-32α was dependent on the PKC activator PMA, we tested various PKC inhibitors. The pan-PKC inhibitor Gö6850 and the PKCϵ inhibitor Ro-31-8220 abrogated the augmenting effect of IL-32α on IL-6 production, whereas the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976 and the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin did not. In addition, IL-32α was co-immunoprecipitated with PMA-activated PKCϵ, and this interaction was totally inhibited by the PKCϵ inhibitor Ro-31-8220. PMA-induced enhancement of STAT3 phosphorylation was observed only in IL-32α-expressing cells, and this enhancement was inhibited by Ro-31-8220, but not by Gö6976. We demonstrate that IL-32α mediated STAT3 phosphorylation by forming a trimeric complex with PKCϵ and enhanced STAT3 localization onto the IL-6 promoter and thereby increased IL-6 expression. Thus, our data indicate that the intracellular interaction of IL-32α with PKCϵ and STAT3 promotes STAT3 binding to the IL-6 promoter by enforcing STAT3 phosphorylation, which results in increased production of IL-6.

Introduction

IL-32 is known as a multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine produced by various types of cells, including T cells, natural killer cells, monocytes, epithelial cells, and vascular endothelial cells. Elevated IL-32 levels have been associated with several inflammatory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1), rheumatoid arthritis (2), and Crohn disease (3).

Interestingly, despite that IL-32 has been studied as a secretable factor for its proinflammatory function, its cognate receptor has not yet been identified. Some reports have shown that IL-32 is detected mostly in cell lysates rather than in culture supernatants (3–8). Some reports have also indicated that IL-32β is the most abundant isoform among six splice variants (IL-32α, IL-32β, IL-32γ, IL-32δ, IL-32ϵ, and IL-32ζ) and that it is involved in the activation-induced cell death of T cells (4, 5). IL-32β and IL-32γ are also known to induce the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (9, 10). It was recently reported that IL-32α overexpression in chronic myeloid cells increases natural killer cell-mediated killing (11). IL-32α is known to be strongly expressed in pancreatic cancer cells (12). In addition, the interaction of IL-32α with integrin as well as paxillin through its α-helix bundle structure was reported (13). These data suggest the existence of isoform-specific or cell type-specific functional differences among IL-32 isoforms; however, it is unclear whether IL-32 has intracellular functions.

PKC is a family of serine/threonine kinases that are known to be involved in cell growth, migration, and inflammation (14). Specific PKC isoforms are crucial to the regulation of myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic development (15–18). A variety of tissues, such as those of the nervous, cardiac, and immune systems, express PKCϵ, and the role of PKCϵ is important for their proper function (19–22). PKCϵ may be a useful therapeutic target to treat disease conditions, such as inflammation (19), ischemia (23), addiction (24), pain (25), anxiety (26, 27), and cancer (28, 29).

IL-6 expression has been shown to be regulated by several PKC isoforms (30, 31). IL-6 production is induced by PKC via various signaling pathways, but it is only slightly induced by the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)2 alone (32). STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) is also known to induce IL-6 production in starved cancer cells, whereas JAK1/STAT3 signaling is known to mediate IL-6 signaling (33–35). Several studies have shown that PKCϵ interacts with STAT3 to induce its constitutive activation in prostate cancer and skin cancer (36, 37). Although previous studies have provided evidence for its action as a soluble inducer of inflammation, our study shows an unexpected action of IL-32, namely its interaction with PKCϵ and STAT3 in elevating IL-6 production as an intracellular mediator.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Cell Culture

The human promyelomonocytic THP-1 cell line was grown in RPMI 1640 medium (WelGENE, Taegu, Korea) supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). PMA was purchased from Sigma. MAPK inhibitors (PD98059, SB203580, and SP100625) and PKC inhibitors (Gö6850, Gö6976, Ro-31-8220, and rottlerin) were purchased from Calbiochem.

Construction of Expression Vectors and IL-6 Reporter Plasmid

The pcDNA3.1+-6×Myc vector was generated by inserting the 6×Myc tag from the pCS3MT vector and then subcloning IL-32α cDNA into this vector using EcoRI and XhoI. STAT3 cDNA was PCR-amplified from the human spleen cDNA library (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and subcloned into pCS3MT-6×Myc. A 5×FLAG tag was generated by ligating hybridized 5′-phosphorylated sense and antisense DNA strands of the FLAG tag sequence (Xenotech, Daejeon, Korea), and the tag was then inserted into pcDNA3.1+. cDNAs for PKCα, PKCδ, PKCϵ, PKCθ, and retinoid X receptor were synthesized by RT-PCR of total RNA collected from THP-1 cells; they were then PCR-amplified and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1+-5×FLAG vector using EcoRI and XhoI. The IL-6 promoter region (−1145 to +19) was PCR-amplified from THP-1 genomic DNA. The primer set was 5′-GGTACCATCCTGAGGGGAAGAGGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCTCCTGGAGGGGAGATAGAGCTT-3′ (antisense). The PCR product was digested with NheI and XhoI restriction enzymes. The digested fragment (−226 to +14) was ligated into the pGL3-Basic vector.

Establishment of Stable Cell Lines

To establish constitutive expression systems of IL-32α, THP-1 promonocytic cells were transfected with the pcDNA3.1+-6×Myc or pcDNA3.1+-6×Myc-IL-32α vector using the NeonTM transfection system (Invitrogen). G418 (900 μg/ml)-resistant cells were screened for 3 weeks, and single cell-expanded clones were obtained by serial dilutions.

Measurement of IL-6 Expression Levels and IL-6 Promoter Activity

IL-6 mRNA expression was detected by RT-PCR of total RNAs extracted from THP-1 cells expressing empty vector (THP-1-EV cells) or IL-32α (THP-1-IL-32α cells) after the various treatments during the experiments. The IL-6 primer set used for PCR was 5′-TACATCCTCGACGGCATCTCA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTACATTTGCCGAAGAGCCCT-3′ (antisense). IL-6 ELISA was performed using an IL-6 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). pGL3-IL-6 promoter (0.5 μg), pRL-null (Renilla, 0.5 μg), STAT3 (1 μg), and PKCϵ (1 μg) expression vectors were cotransfected into HEK293 cells with or without the IL-32α expression vector (1 μg). Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase® reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI).

Western Blotting and Immunoprecipitation

HEK293 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3.1+-6×Myc-IL-32α and pcDNA3.1+-5×FLAG-PKC and then lysed in 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, 20 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 1 mm EDTA. Western blotting was performed using anti-Myc tag antibody (Millipore, Bedford, MA); anti-FLAG tag antibody (Sigma); and anti-PKCϵ, anti-IκBα, and anti-STAT3 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Anti-phospho-STAT3 antibody was purchased from Millipore. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were mixed with 1 μg of anti-Myc antibody, 3 μg of anti-PKCϵ antibody, 3 μg of anti-STAT3 antibody, or 5 μg of anti-IL-32 antibody KU32-52(9, 38) for 1 h and then pulled down using 35 μl of protein G-agarose beads (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD).

ChIP Assay

For this experiment, we used a commercially available ChIP assay kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, THP-1-IL-32α cells were treated with PKC inhibitors for 1 h, and then both THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells were treated with PMA for 3 h, including inhibitor-treated samples. The cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, lysed with kit lysis buffer, and sonicated with five pulses for 5 s each. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min, the supernatants were mixed with anti-Myc tag antibody or normal mouse IgG and maintained overnight. Protein A-agarose/salmon sperm DNA (60 μl, 50% slurry) was added to each sample, and the pulled down DNA fragments were eluted. PCR amplification using the eluted DNA as the template was performed for 35 cycles at an annealing temperature of 59 °C. The primers used for PCR amplification of the IL-6 promoter were 5′-GTCACATTGCACAATCTTAAT-3′ (sense, −162 to −142) and 5′-GAGCCTCAGACATCTCCAGTC-3′ (antisense, −21 to −1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was analyzed by Student's unpaired two-tailed t test.

RESULTS

IL-32α Up-regulates IL-6 Production upon PMA Stimulation

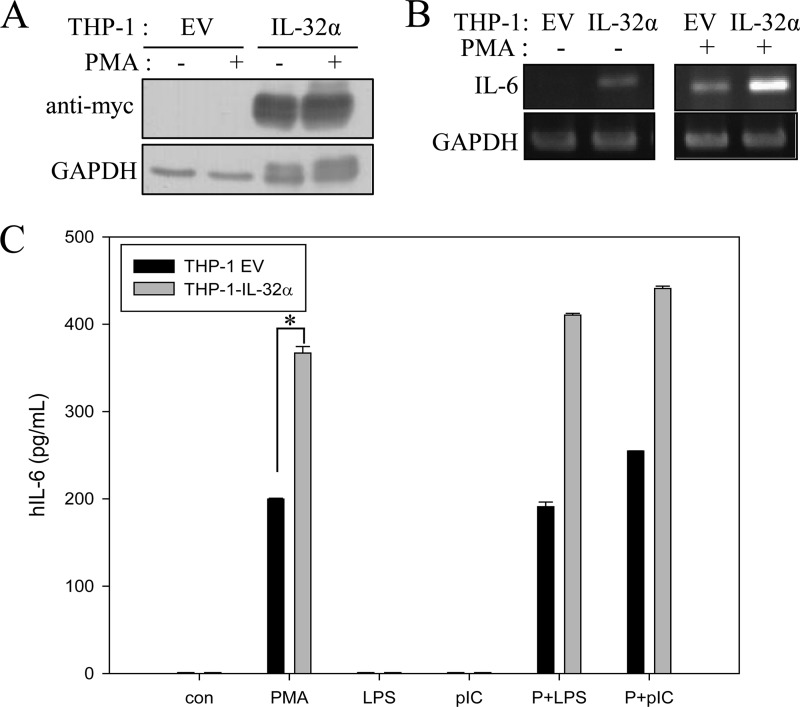

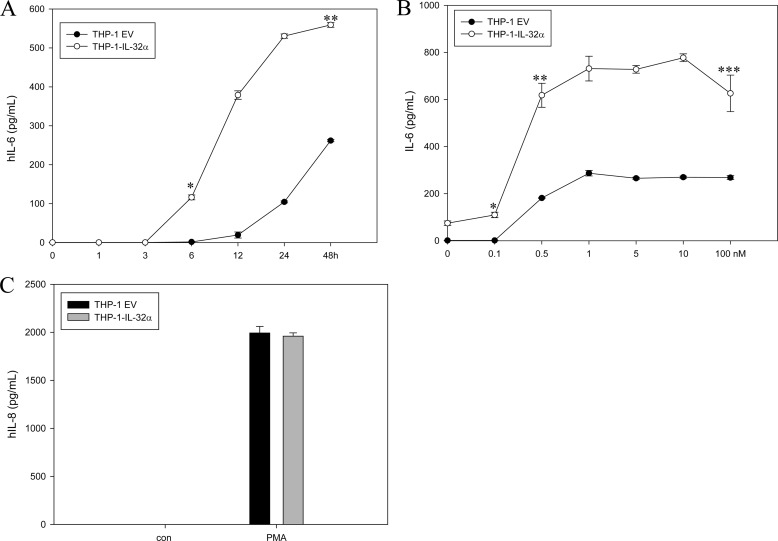

We generated a stable expression system for IL-32α by transfecting THP-1 promonocytic cells with 6×Myc-tagged IL-32α because the endogenous IL-32α protein is hardly detected in contrast with its transcript (Fig. 1A). Western blotting did not reveal any IL-32 isoform with THP-1 cells. Only the IL-32β transcript was identified by RT-PCR and sequencing (data not shown). We observed that the IL-6 transcript was weakly expressed by IL-32α overexpression, but upon treatment with 10 nm PMA, the levels of IL-6 transcripts in THP-1-IL-32α cells were markedly higher than those in THP-1-EV cells. In THP-1-EV cells, PMA stimulation resulted only in minimal expression of IL-6 mRNA (Fig. 1B). We examined the effect of other stimulants (LPS and poly(I:C)) on IL-6 induction in both cell lines. These stimulants did not induce IL-6 even though they slightly enhanced IL-6 production upon co-treatment with PMA (Fig. 1C). We further confirmed that the effect of PMA on IL-6 production was time- and dose-dependent. In THP-1-IL-32α cells, the IL-6 protein was detected in the culture medium even at 3 h after PMA stimulation, and the protein levels increased steeply until 48 h. However, in THP-1-EV cells, the amount of IL-6 secretion was less than half that in THP-1-IL-32α cells at 48 h (Fig. 2A). In the dose-related experiment, IL-6 production in THP-1-IL-32α cells was more than three times that in empty vector cells (Fig. 2B). The levels of IL-1β and TNFα were below the detection limit in both cell lines (data not shown). IL-8 levels were also increased by PMA treatment, but the expression levels were similar in THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 1.

A, constitutive expression systems of 6×Myc-tagged IL-32α were established in THP-1 promonocytic cells. IL-32α expression was confirmed using anti-Myc antibody with or without 10 nm PMA treatment. B, THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells were treated with 10 nm PMA for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted. The IL-6 transcript level was analyzed by RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as a loading control. C, THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells were treated with 10 nm PMA (P), 1 μg/ml LPS, 10 μg/ml poly(I:C) (pIC), and PMA + LPS, or PMA + poly(I:C) for 24 h, and the culture media were collected for IL-6 ELISA. *, p < 0.005 (THP-1-EV cells versus THP-1-IL-32α cells for PMA treatment). Values are means ± S.E. hIL-6, human IL-6.

FIGURE 2.

IL-32α increases IL-6 production in PMA-dependent manner. A and B, IL-6 levels were assessed by ELISA after time- and dose-dependent PMA treatment of THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells. Culture media were collected at the indicated time points after 10 nm PMA treatment. A: * and **, p < 0.001 (THP-1-EV cells versus THP-1-IL-32α cells at 6 and 48 h, respectively). B: * and **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.01 (THP-1-EV cells versus THP-1-IL-32α cells at 24 h after dose-dependent treatment of PMA at 0.1, 0.5, and 100 nm, respectively). hIL-6, human IL-6. C, expression levels of IL-8 were measured by ELISA with samples treated for 24 h with PMA. All values are means ± S.E. These experiments were performed three times in triplicate, and representative results are shown.

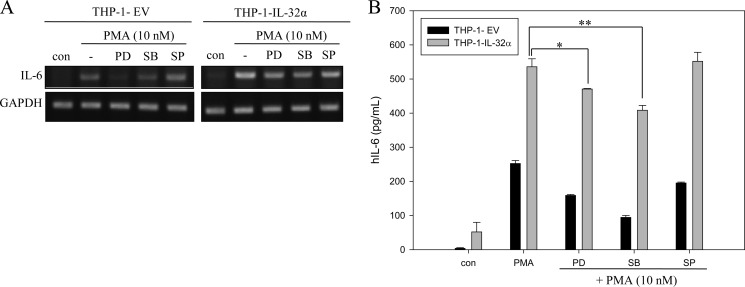

MAPK Does Not Contribute to IL-32α-induced Up-regulation of IL-6 Production

We examined whether MAPK signaling mediates the effect of IL-32α on IL-6 production because IL-32 is known to activate p38 signaling pathways (39). When THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells were treated with PD98059 for ERK inhibition, SB203580 for p38 inhibition, and SP600125 for JNK inhibition, the up-regulated production of IL-6 at both the mRNA and protein levels was sustained for longer periods of time in THP-1-IL-32α cells than in THP-1-EV cells (Fig. 3, A and B), although p38 or ERK inhibition affected IL-6 production compared with PMA-alone treatment in both cell lines (Fig. 3B). This may be because p38 or ERK is also involved in IL-6 induction. JNK did not seem to be involved in IL-6 production in this system as described elsewhere (40, 41). Our data imply that the augmented production of IL-6 by IL-32α was not mediated by MAPK signaling pathways and that other signal molecules may be involved in the augmenting effect of IL-32α on IL-6 production by THP-1 cells.

FIGURE 3.

MAPKs do not contribute to IL-32α-induced up-regulation of IL-6 production by PMA stimulation. Cells were pretreated with ERK inhibitor PD98059 (PD; 25 μm), p38 inhibitor SB203580 (SB; 10 μm), and JNK inhibitor SP600125 (SP; 20 μm) for 1 h before 10 nm PMA treatment. After a 24-h incubation, total RNAs were extracted for RT-PCR (A), and culture media were collected for ELISA (B). All values are means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05 (PMA-treated IL-32α cells versus PD98059-treated IL-32α cells); **, p < 0.05 (PMA-treated IL-32α cells versus SB203580-treated IL-32α cells). The experiments were repeated more than three times, and representative results are shown. ELISA was performed in triplicate. hIL-6, human IL-6.

PKCϵ Is Involved in Enhanced Production of IL-6 by IL-32α

We expected the involvement of a certain type of PKC because the increase in IL-6 production by IL-32α was PMA-dependent. As shown in Fig. 4 (A and B), the increase in IL-6 production by IL-32α was totally abrogated by the pan-PKC inhibitor Gö6850, but not by the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976. This implies that PKCs other than the classical PKCs may be involved in the IL-32α effect. Nonetheless, it appears that classical PKCs were involved in IL-6 production by a mechanism not involving IL-32α because IL-6 production was decreased by Gö6976 treatment in THP-1-EV cells (Fig. 4, A and B). We treated the cells with rottlerin, a PKCδ inhibitor, or Ro-31-8220, which inhibits classical PKCs and PKCϵ among novel PKCs. As shown in Fig. 4 (C and D), Ro-31-8220 treatment totally abrogated the augmenting effect of IL-32α on IL-6 production. Rottlerin also decreased IL-6 production in both THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells, but IL-6 production was still maintained at higher levels in THP-1-IL-32α cells than in THP-1-EV cells; this implies that PKCδ has a minor effect on the augmented production of IL-6 by IL-32α.

FIGURE 4.

PKCϵ is involved in augmentation of IL-6 production by IL-32α. A and B, various PKC inhibitors were used to screen contributive PKCs for the IL-32α effect on IL-6 up-regulation. THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells were pretreated with the pan-PKC inhibitor Gö6850 (6850; 10 μm) and the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976 (6976; 10 μm) for 1 h before 10 nm PMA treatment for 24 h. The IL-6 transcript and protein levels were then measured by RT-PCR (A) and ELISA (B), respectively. *, p < 0.001 (PMA-treated versus Gö6976-treated THP-1-EV cells). hIL-6, human IL-6. C and D, cells were treated with the PKCϵ-specific inhibitor Ro-31-8220 (Ro31; 10 μm) and the PKCδ-specific inhibitor rottlerin (Rot; 10 μm). Both the IL-6 mRNA (C) and protein (D) levels were analyzed in the same manner. All values are means ± S.E. *, p < 0.01 (PMA-treated versus rottlerin-treated IL-32α); **, p < 0.001 (rottlerin-treated THP-1-EV cells versus rottlerin-treated THP-1-IL-32α cells). The experiments were repeated three to four times, and representative results are shown. ELISA was performed in triplicate.

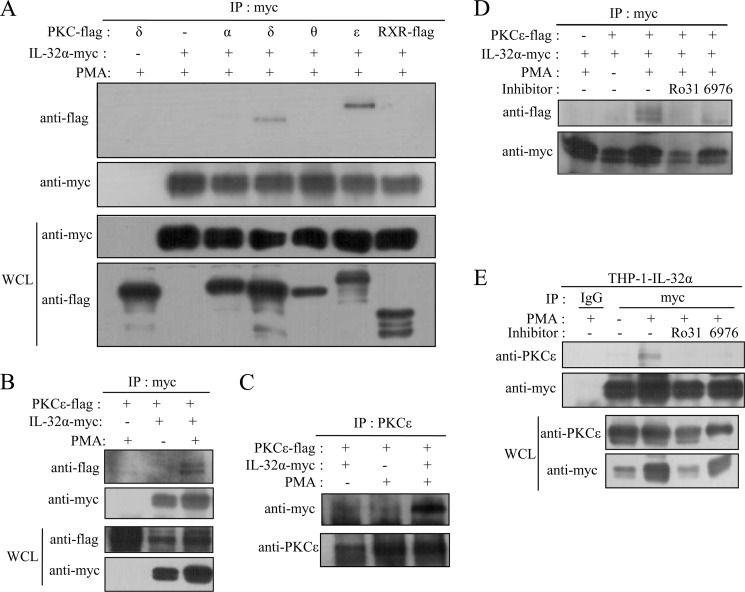

PMA-activated PKCϵ Interacts with IL-32α

To investigate how PKCs are involved in IL-32α-induced augmentation of IL-6 production, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments after cotransfecting HEK293 cells with 6×Myc-tagged IL-32α and each PKC isoform (α, δ, ϵ, and θ) tagged with the 5×FLAG. Consistent with the results shown in Fig. 4, IL-32α was found to interact with PKCϵ and PKCδ. The extent of interaction of IL-32α with PKCδ was weaker than that with PKCϵ (Fig. 5A), as expected from the results of Fig. 4 (C and D). IL-32α interacted with PMA-activated PKCϵ (Fig. 5, B and C). The interaction between IL-32α and PKCϵ was further verified by immunoprecipitation after cotransfection of HEK293 cells with both expression vectors or in THP-1-IL-32α cells. As shown in Fig. 5D, IL-32α was immunoprecipitated with PKCϵ upon PMA treatment. This interaction was suppressed by the PKCϵ-specific inhibitor Ro-31-8220. These data indicate that PMA-activated PKCϵ binds to IL-32α. Fig. 5E shows IL-32α co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous PKCϵ upon PMA stimulation in THP-1-IL-32α cells, and this interaction was blocked by Ro-31-8220 treatment. Although the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976 affected this interaction, the association was still maintained (Fig. 5D). These data imply that PKCϵ is the major factor involved in the effect of IL-32α on IL-6 production.

FIGURE 5.

IL-32α interacts with PMA-activated PKCϵ. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Myc-tagged IL-32α expression vector and each FLAG-tagged PKC isoform (α, δ, ϵ, and θ) expression vector. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 30 nm PMA for 3 h. Immunoprecipitation (IP) with 1 μg of anti-Myc antibody was performed, and the pulled down PKCs were detected with anti-FLAG antibody. Retinoid X receptor (RXR) was used as a negative control, and PKCδ alone (first lane) was used as an immunoprecipitation control for probing specific interactions (A). The interaction between PKCϵ and IL-32α was confirmed by immunoprecipitation with 1 μg of anti-Myc antibody (B) or 1.5 μg of anti-PKCϵ antibody (C) after cotransfection into HEK293 cells with or without 30 nm PMA treatment for 3 h. The specific interaction between PKCϵ and IL-32α was tested by treatment of HEK293 cells after cotransfection (D) and THP-1-IL-32α cells (E) with the PKCϵ-specific inhibitor Ro-31-8220 (Ro31; 10 μm) and the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976 (6976; 10 μm). Normal mouse IgG was used as a negative control. The expression levels of the transfected genes were determined by Western blotting with 20 μg of whole cell lysates (WCL). Immunoprecipitation experiments were repeated three to four times, and representative results are shown.

IL-32α Does Not Modulate NF-κB Signaling but Reinforces STAT3 Phosphorylation through Forming Trimeric Complex with PKCϵ

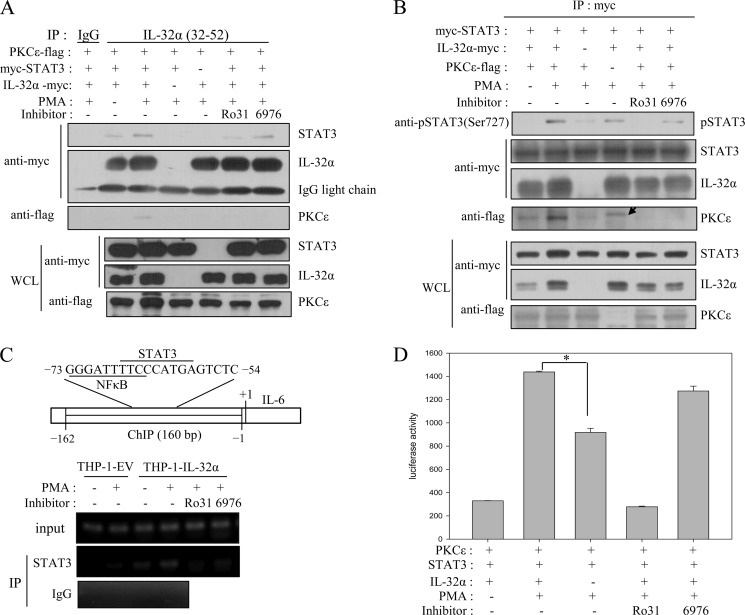

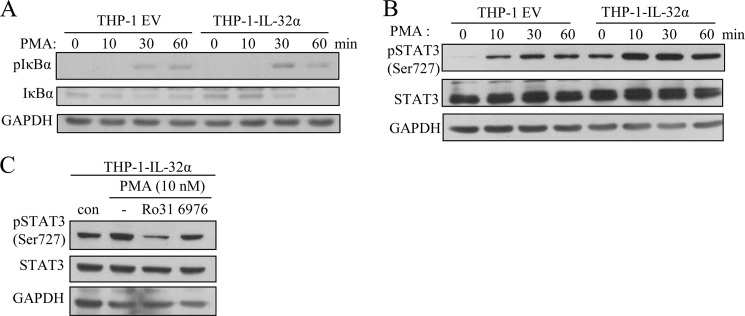

Various cytokines, including IL-6, are known to be induced by NF-κB signaling. In fact, the NF-κB consensus sequence is found on the IL-6 promoter (42, 43). Interestingly, the NF-κB-binding sequence partially overlaps with the STAT3 consensus sequence (see Fig. 7C), which suggests that STAT3 also contributes to IL-6 induction. STAT3 and NF-κB have been reported to cooperatively induce IL-6 (35). On the basis of these facts, we examined NF-κB signaling and STAT3 phosphorylation status after PMA treatment of THP-1-EV and THP-1-IL-32α cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, phospho-IκBα was increased by PMA treatment, whereas IκBα was gradually degraded in both cell lines. This implies that NF-κB signaling was not changed by IL-32α. However, PMA treatment induced greater STAT3 (Ser-727) phosphorylation in THP-1-IL-32α cells than in THP-1-EV cells (Fig. 6B). The phosphorylation of STAT3 was suppressed by Ro-31-8220 treatment, but not by Gö6976 treatment (Fig. 6C). Thus, these data indicate that IL-32α modulates STAT3 signaling via PKCϵ, but not NF-κB signaling. We further delineated the relationship between PKCϵ, IL-32α, and STAT3. The immunoprecipitation assay revealed that the interaction of IL-32α with STAT3 and PKCϵ resulted in the formation of a trimeric complex. As shown in Fig. 7A, IL-32α co-immunoprecipitated with STAT3 as well as PKCϵ. Trimeric complex formation was dependent on PKCϵ activation because Ro-31-8220 inhibited complex formation. These data imply that PKCϵ phosphorylates STAT3, which is mediated by IL-32α.

FIGURE 7.

IL-32α interacts simultaneously with STAT3 and PKCϵ, mediates STAT3 phosphorylation by PKCϵ, and increases IL-6 gene expression. A, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 6×Myc-tagged IL-32α and STAT3 and 5×FLAG-tagged PKCϵ. Cells were treated with 20 nm PMA for 90 min. For inhibitor-treated samples, cells were treated with 10 μm Ro-31-8220 (Ro31) or 10 μm Gö6976 (6976) 1 h before PMA treatment. Immunoprecipitations (IP) with 5 μg of anti-IL-32 antibody (KU32-52) and normal mouse IgG were conducted. The levels of IgG light chain bands show constant loadings. B, HEK293 cell lysates were prepared in the same way and then immunoprecipitated with 1.5 μg of anti-Myc antibody and analyzed for phospho-STAT3 (Ser-727) and pulled down PKCϵ. The arrow indicates an unidentified band. C, the expression levels of the transfected genes were determined by Western blotting with 20 μg of whole cell lysates (WCL). ChIP was performed with 3 μg of anti-STAT3 antibody and normal rabbit IgG, and then the immunoprecipitated IL-6 promoter with STAT3 was PCR-amplified. The schematic diagram shows the ChIP region (160 bp) of the IL-6 promoter. D, IL-6 promoter-firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (0.5 μg), STAT3 (1 μg), and PKCϵ (1 μg) were cotransfected into HEK293 cells with or without IL-32α expression vector (1 μg). After overnight incubation, cells were treated with 20 nm PMA for an additional 24 h. Cells were treated with 10 μm Ro-31-8220 or 10 μm Gö6976 1h before PMA treatment of inhibitor-treated samples. All values are means ± S.E. *, p < 0.0001 (presence versus absence of IL-32α).

FIGURE 6.

IL-32α enhances STAT3 phosphorylation upon PMA stimulation but does not modulate NF-κB signaling. A and B, THP-1-empty vector and THP-1-IL-32α cells were harvested at the indicated time points after treatment with 10 nm PMA. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE; transferred to PVDF membrane; and analyzed for IκBα and phospho-IκBα (A) and phospho-STAT3 (B) by Western blotting. C, THP-1-IL-32α cells were treated with 10 μm Ro-31-8220 (Ro31) or 10 μm Gö6976 (6976) for 1 h before 10 nm PMA treatment for 1 h. STAT3 phosphorylation was suppressed by the PKCϵ inhibitor Ro-31-8220, but not by the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976. We repeated these experiments three to four times for confirmation.

IL-32α Reinforces STAT3 Phosphorylation by PKCϵ and Augments IL-6 Gene Expression by Promoting STAT3 Localization onto IL-6 Promoter

Next, we investigated whether IL-32α mediates the phosphorylation of STAT3 by PKCϵ. After cotransfecting Myc-tagged STAT3 with or without IL-32α into HEK293 cells, Myc-tagged STAT3 was immunoprecipitated and then analyzed for phospho-STAT3 using phospho-STAT3 (Ser-727) antibody (Fig. 7B). STAT3 Ser-727 was phosphorylated in the presence of IL-32α upon PMA stimulation, but in the absence of IL-32α, its phosphorylation was significantly decreased. It is obvious that PKCϵ phosphorylates STAT3 Ser-727 because STAT3 Ser-727 phosphorylation was inhibited by Ro-31-8220, but not by Gö6976. PKCϵ co-immunoprecipitated with IL-32α as well as STAT3. On the other hand, we observed STAT3 phosphorylation despite no input of PKCϵ (Fig. 7B, fourth lane). This effect may be attributed to endogenous PKCϵ because HEK293 cells are known to express all types of PKC isoforms (44). Using ChIP, we next demonstrated that the enhanced phosphorylation of STAT3 by IL-32α induced a greater amount of STAT3 to present on the IL-6 promoter (Fig. 7C). STAT3 localization onto the IL-6 promoter was severely suppressed by the PKCϵ inhibitor Ro-31-8220, but not by the classical PKC inhibitor Gö6976. The effect of IL-32α on IL-6 promoter activity was analyzed by cotransfecting HEK293 cells with STAT3 and PKCϵ expression vectors. As shown in Fig. 7D, in the absence of IL-32α, IL-6 reporter activity was decreased to almost half that in the presence of IL-32α. The reporter activity was suppressed to the basal level by Ro-31-8220, but was not inhibited by Gö6976. Consequently, these data reveal a novel intracellular regulatory role of IL-32α, i.e. IL-32α mediates STAT3 phosphorylation via a novel PKCϵ and promotes STAT3 localization onto IL-6 promoter, and this effect augments IL-6 production.

DISCUSSION

IL-32 is known to be a proinflammatory cytokine and probably exerts its effects by binding to its cell surface receptor, although the receptor has not yet been identified. Although various cell types, including T cells, natural killer cells, monocytes, macrophages, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells, are known to express IL-32, not many cell types have been reported to secrete this molecule. IL-32 has even been reported to be a membrane-associated protein that is released via a non-classical secretory pathway (45). IL-32 seems to be multifunctional because it has been shown to induce proinflammatory cytokines (8, 39, 46), apoptosis (4, 47), and cell differentiation (48, 49).

A recent report indicated that IL-32α and IL-32β interact with integrin and that IL-32α binds to paxillin and FAK1 (focal adhesion kinase 1), which implies that IL-32 may be involved in the formation of the focal adhesion protein complex (13). In this study, we found for the first time that IL-32α interacts with PKCϵ and STAT3 upon PMA stimulation and thereby up-regulates IL-6 production. Many reports have indicated that IL-32 induces IL-6, but the precise mechanism remains elusive. Our data suggest that IL-32α functions intracellularly through interaction with PKCϵ and STAT3. We also found that IL-32α interacts with PKCδ (Fig. 4A). These results imply that IL-32α may be an adaptor protein for PKC, which is known to be a receptor for activated C kinase (RACK). RACK1 is an anchoring protein for activated PKCβII that mediates the binding of Src tyrosine kinase, integrin, and phosphodiesterase. PKCϵ-specific RACK2 is a coated vesicle protein that is involved in vesicular release and cell-to-cell communication (50). RACK1 and RACK2 interact with their specific partners, PKCβII and PKCϵ, respectively. Ten isotypes of PKCs have been identified, and it is thought that every PKC may have a specific RACK.

PKCϵ induces prostate cancer or skin cancer by phosphorylating STAT3. PKCδ has also been known to interact with and phosphorylate STAT3 Ser-727 (51). Although a previous report indicated that the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin inhibited IL-6 production in a PKCδ-independent manner (52), our data show that IL-6 production was only slightly inhibited by rottlerin in IL-32α-expressing cells, which suggests that PKCδ may be implicated in IL-32α-mediated IL-6 up-regulation to some extent. In the conventional pathway, STAT3 is activated by IL-6 signaling. However, in this study, we showed that the interaction of IL-32α with PKCϵ and STAT3 induces STAT3 Ser-727 phosphorylation and enhances IL-6 production.

This work was supported by Basic Program Grants 2010-0019306 and 2012R1A2A2A 02008751 from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), NRF Grant 2009-R1AAA002-351-2009-1-E00007 (to J.-W. K.), and Priority Research Centres Program Grant 2012-0006686 (to D.-Y. Y.).

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- EV

- empty vector

- RACK

- receptor for activated C kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Calabrese F., Baraldo S., Bazzan E., Lunardi F., Rea F., Maestrelli P., Turato G., Lokar-Oliani K., Papi A., Zuin R., Sfriso P., Balestro E., Dinarello C. A., Saetta M. (2008) IL-32, a novel proinflammatory cytokine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 178, 894–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mun S. H., Kim J. W., Nah S. S., Ko N. Y., Lee J. H., Kim J. D., Kim do K., Kim H. S., Choi J. D., Kim S. H., Lee C. K., Park S. H., Kim B. K., Kim H. S., Kim Y. M., Choi W. S. (2009) Tumor necrosis factor α-induced interleukin-32 is positively regulated via the Syk/protein kinase Cδ/JNK pathway in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 678–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shioya M., Nishida A., Yagi Y., Ogawa A., Tsujikawa T., Kim-Mitsuyama S., Takayanagi A., Shimizu N., Fujiyama Y., Andoh A. (2007) Epithelial overexpression of interleukin-32α in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 149, 480–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goda C., Kanaji T., Kanaji S., Tanaka G., Arima K., Ohno S., Izuhara K. (2006) Involvement of IL-32 in activation-induced cell death in T cells. Int. Immunol. 18, 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kobayashi H., Lin P. C. (2009) Molecular characterization of IL-32 in human endothelial cells. Cytokine 46, 351–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Netea M. G., Azam T., Lewis E. C., Joosten L. A., Wang M., Langenberg D., Meng X., Chan E. D., Yoon D. Y., Ottenhoff T., Kim S. H., Dinarello C. A. (2006) Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces interleukin-32 production through a caspase-1/IL-18/interferon-γ-dependent mechanism. PLoS Med. 3, e277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nishida A., Andoh A., Shioya M., Kim-Mitsuyama S., Takayanagi A., Fujiyama Y. (2008) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling mediates interleukin-32α induction in human pancreatic periacinar myofibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. 294, G831–G838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nold-Petry C. A., Nold M. F., Zepp J. A., Kim S. H., Voelkel N. F., Dinarello C. A. (2009) IL-32-dependent effects of IL-1α on endothelial cell functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3883–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kang J. W., Choi S. C., Cho M. C., Kim H. J., Kim J. H., Lim J. S., Kim S. H., Han J. Y., Yoon D. Y. (2009) A proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-32β promotes the production of an anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10. Immunology 128, e532–e540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choi J., Bae S., Hong J., Ryoo S., Jhun H., Hong K., Yoon D., Lee S., Her E., Choi W., Kim J., Azam T., Dinarello C. A., Kim S. (2010) Paradoxical effects of constitutive human IL-32γ in transgenic mice during experimental colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21082–21086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheon S., Lee J. H., Park S., Bang S. I., Lee W. J., Yoon D. Y., Yoon S. S., Kim T., Min H., Cho B. J., Lee H. J., Lee K. W., Jeong S. H., Park H., Cho D. (2011) Overexpression of IL-32α increases natural killer cell-mediated killing through up-regulation of Fas and UL16-binding protein 2 (ULBP2) expression in human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12049–12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishida A., Andoh A., Inatomi O., Fujiyama Y. (2009) Interleukin-32 expression in the pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17868–17876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heinhuis B., Koenders M. I., van den Berg W. B., Netea M. G., Dinarello C. A., Joosten L. A. (2012) Interleukin 32 (IL-32) contains a typical α-helix bundle structure that resembles focal adhesion targeting region of focal adhesion kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 5733–5743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Newton A. C. (1995) Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28495–28498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kovanen P. E., Junttila I., Takaluoma K., Saharinen P., Valmu L., Li W., Silvennoinen O. (2000) Regulation of Jak2 tyrosine kinase by protein kinase C during macrophage differentiation of IL-3-dependent myeloid progenitor cells. Blood 95, 1626–1632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lumelsky N. L., Schwartz B. S. (1997) Protein kinase C in erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation: possible role in lineage determination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1358, 79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mischak H., Pierce J. H., Goodnight J., Kazanietz M. G., Blumberg P. M., Mushinski J. F. (1993) Phorbol ester-induced myeloid differentiation is mediated by protein kinase Cα and -δ and not by protein kinase CβII, -ϵ, -ζ, and -η. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 20110–20115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tonetti D. A., Henning-Chubb C., Yamanishi D. T., Huberman E. (1994) Protein kinase Cβ is required for macrophage differentiation of human HL-60 leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23230–23235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aksoy E., Goldman M., Willems F. (2004) Protein kinase Cϵ: a new target to control inflammation and immune-mediated disorders. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Churchill E. N., Mochly-Rosen D. (2007) The roles of PKCδ and -ϵ isoenzymes in the regulation of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1040–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shirai Y., Adachi N., Saito N. (2008) Protein kinase Cϵ: function in neurons. FEBS J. 275, 3988–3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Van Kolen K., Pullan S., Neefs J. M., Dautzenberg F. M. (2008) Nociceptive and behavioral sensitization by protein kinase Cϵ signaling in the CNS. J. Neurochem. 104, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Budas G. R., Mochly-Rosen D. (2007) Mitochondrial protein kinase Cϵ (PKCϵ): emerging role in cardiac protection from ischemic damage. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1052–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Newton P. M., Messing R. O. (2006) Intracellular signaling pathways that regulate behavioral responses to ethanol. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khasar S. G., Lin Y. H., Martin A., Dadgar J., McMahon T., Wang D., Hundle B., Aley K. O., Isenberg W., McCarter G., Green P. G., Hodge C. W., Levine J. D., Messing R. O. (1999) A novel nociceptor signaling pathway revealed in protein kinase Cϵ mutant mice. Neuron 24, 253–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hodge C. W., Raber J., McMahon T., Walter H., Sanchez-Perez A. M., Olive M. F., Mehmert K., Morrow A. L., Messing R. O. (2002) Decreased anxiety-like behavior, reduced stress hormones, and neurosteroid supersensitivity in mice lacking protein kinase Cϵ. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1003–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lesscher H. M., McMahon T., Lasek A. W., Chou W. H., Connolly J., Kharazia V., Messing R. O. (2008) Amygdala protein kinase Cϵ regulates corticotropin-releasing factor and anxiety-like behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 7, 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Basu A., Sivaprasad U. (2007) Protein kinase Cϵ makes the life and death decision. Cell. Signal. 19, 1633–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gorin M. A., Pan Q. (2009) Protein kinase Cϵ: an oncogene and emerging tumor biomarker. Mol. Cancer 8, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fima E., Shahaf G., Hershko T., Apte R. N., Livneh E. (1999) Expression of PKCη in NIH-3T3 cells promotes production of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 10, 491–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garcia-Zepeda E. A., Rothenberg M. E., Ownbey R. T., Celestin J., Leder P., Luster A. D. (1996) Human eotaxin is a specific chemoattractant for eosinophil cells and provides a new mechanism to explain tissue eosinophilia. Nat. Med. 2, 449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kiriyama Y., Tsuchiya H., Murakami T., Satoh K., Tokumitsu Y. (2001) Calcitonin induces IL-6 production via both PKA and PKC pathways in the pituitary folliculostellate cell line. Endocrinology 142, 3563–3569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murray P. J. (2007) The JAK-STAT signaling pathway: input and output integration. J. Immunol. 178, 2623–2629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoon S., Woo S. U., Kang J. H., Kim K., Kwon M. H., Park S., Shin H. J., Gwak H. S., Chwae Y. J. (2010) STAT3 transcriptional factor activated by reactive oxygen species induces IL-6 in starvation-induced autophagy of cancer cells. Autophagy 6, 1125–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoon S., Woo S. U., Kang J. H., Kim K., Shin H. J., Gwak H. S., Park S., Chwae Y. J. (2012) NF-κB and STAT3 cooperatively induce IL-6 in starved cancer cells. Oncogene 31, 3467–3481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aziz M. H., Manoharan H. T., Sand J. M., Verma A. K. (2007) Protein kinase Cϵ interacts with Stat3 and regulates its activation that is essential for the development of skin cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 46, 646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aziz M. H., Manoharan H. T., Church D. R., Dreckschmidt N. E., Zhong W., Oberley T. D., Wilding G., Verma A. K. (2007) Protein kinase Cϵ interacts with signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (Stat3), phosphorylates Stat3 Ser-727, and regulates its constitutive activation in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 8828–8838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim K. H., Shim J. H., Seo E. H., Cho M. C., Kang J. W., Kim S. H., Yu D. Y., Song E. Y., Lee H. G., Sohn J. H., Kim J., Dinarello C. A., Yoon D. Y. (2008) Interleukin-32 monoclonal antibodies for immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and ELISA. J. Immunol. Methods 333, 38–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim S. H., Han S. Y., Azam T., Yoon D. Y., Dinarello C. A. (2005) Interleukin-32: a cytokine and inducer of TNFα. Immunity 22, 131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pathak S. K., Basu S., Bhattacharyya A., Pathak S., Banerjee A., Basu J., Kundu M. (2006) TLR4-dependent NF-κB activation and mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1-triggered phosphorylation events are central to Helicobacter pylori peptidylprolyl cis,trans-isomerase (HP0175)-mediated induction of IL-6 release from macrophages. J. Immunol. 177, 7950–7958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Georganas C., Liu H., Perlman H., Hoffmann A., Thimmapaya B., Pope R. M. (2000) Regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts: the dominant role for NF-κB but not C/EBPβ or c-Jun. J. Immunol. 165, 7199–7206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ammit A. J., Lazaar A. L., Irani C., O'Neill G. M., Gordon N. D., Amrani Y., Penn R. B., Panettieri R. A., Jr. (2002) Tumor necrosis factor α-induced secretion of RANTES and interleukin-6 from human airway smooth muscle cells: modulation by glucocorticoids and -β-agonists. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 26, 465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eickelberg O., Pansky A., Mussmann R., Bihl M., Tamm M., Hildebrand P., Perruchoud A. P., Roth M. (1999) Transforming growth factor β1 induces interleukin-6 expression via activating protein-1 consisting of JunD homodimers in primary human lung fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12933–12938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kanno T., Yamamoto H., Yaguchi T., Hi R., Mukasa T., Fujikawa H., Nagata T., Yamamoto S., Tanaka A., Nishizaki T. (2006) The linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA selectively activates PKCϵ, possibly binding to the phosphatidylserine-binding site. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1146–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hasegawa H., Thomas H. J., Schooley K., Born T. L. (2011) Native IL-32 is released from intestinal epithelial cells via a non-classical secretory pathway as a membrane-associated protein. Cytokine 53, 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Joosten L. A., Netea M. G., Kim S. H., Yoon D. Y., Oppers-Walgreen B., Radstake T. R., Barrera P., van de Loo F. A., Dinarello C. A., van den Berg W. B. (2006) IL-32, a proinflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3298–3303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heinhuis B., Koenders M. I., van Riel P. L., van de Loo F. A., Dinarello C. A., Netea M. G., van den Berg W. B., Joosten L. A. (2011) Tumor necrosis factor α-driven IL-32 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue amplifies an inflammatory cascade. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 660–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mabilleau G., Sabokbar A. (2009) Interleukin-32 promotes osteoclast differentiation but not osteoclast activation. PLoS ONE 4, e4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Netea M. G., Lewis E. C., Azam T., Joosten L. A., Jaekal J., Bae S. Y., Dinarello C. A., Kim S. H. (2008) Interleukin-32 induces the differentiation of monocytes into macrophage-like cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3515–3520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schechtman D., Mochly-Rosen D. (2001) Adaptor proteins in protein kinase C-mediated signal transduction. Oncogene 20, 6339–6347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jain N., Zhang T., Kee W. H., Li W., Cao X. (1999) Protein kinase Cδ associates with and phosphorylates Stat3 in an interleukin-6-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24392–24400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smyth D. C., Kerr C., Richards C. D. (2006) Oncostatin M-induced IL-6 expression in murine fibroblasts requires the activation of protein kinase Cδ. J. Immunol. 177, 8740–8747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]