Background: ACTN4 potentiates nuclear receptor (NR)-mediated transcriptional activity.

Results: The flanking sequences to the LXXLL motif in ACTN4 are important for both its association with ERα and co-activators.

Conclusion: The ACTN4 (Iso) acts as a more potent co-activator of NRs than the corresponding ACTN4 (full length) through stronger interactions with known co-activators.

Significance: This study describes a novel molecular mechanism by which ACTN4 (Iso) regulates transcription mediated by NRs.

Keywords: Nuclear Receptors, Transcription, Transcription Co-activators, Transcription Regulation, Transcription Target Genes

Abstract

α-Actinins (ACTNs) are a family of proteins cross-linking actin filaments that maintain cytoskeletal organization and cell motility. Recently, it has also become clear that ACTN4 can function in the nucleus. In this report, we found that ACTN4 (full length) and its spliced isoform ACTN4 (Iso) possess an unusual LXXLL nuclear receptor interacting motif. Both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) potentiate basal transcription activity and directly interact with estrogen receptor α, although ACTN4 (Iso) binds ERα more strongly. We have also found that both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) interact with the ligand-independent and the ligand-dependent activation domains of estrogen receptor α. Although ACTN4 (Iso) interacts efficiently with transcriptional co-activators such as p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) and steroid receptor co-activator 1 (SRC-1), the full length ACTN4 protein either does not or does so weakly. More importantly, the flanking sequences of the LXXLL motif are important not only for interacting with nuclear receptors but also for the association with co-activators. Taken together, we have identified a novel extended LXXLL motif that is critical for interactions with both receptors and co-activators. This motif functions more efficiently in a spliced isoform of ACTN4 than it does in the full-length protein.

Introduction

The nuclear hormone receptors (NRs)2 are a family of ligand-activated transcription factors that include receptors for thyroid hormones, vitamin D (VDR), retinoids (RAR and RXR), and steroid hormones (1–4). Nuclear hormone receptors are known to regulate organ homeostasis, cell differentiation, and development by controlling a network of gene expression.

The mechanisms underlying transcriptional regulation by NRs are thought to occur through their association with co-repressors or co-activators. The unliganded receptors adopt a conformation that favors their association with co-repressors. Upon binding to ligands, receptors undergo an allosteric change leading to dissociation of co-repressor complexes and concomitant recruitment of co-activator proteins. The transcriptional co-activators are responsible for marking histones and remodeling chromatin leading to the recruitment of RNA polymerase II to initiate transcription (5, 6). The co-activator proteins often function as components of large complexes that collaborate to potentiate transcriptional activation (4). There are three main classes of co-activators associated with NRs: the p160 family, cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CBP)/p300, and p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF). The well characterized p160 family proteins include steroid receptor co-activator 1 (SRC-1), glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1), and the activator of thyroid and retinoic acid receptor (ACTR) (7). The functional importance of the p160 family lies in the fact that mice lacking p160 genes are defective in nuclear receptor-mediated developmental processes (8–10). Several studies have indicated that hormone-induced interactions between NRs and co-activators is mediated through a single or multiple copies of conserved motif LXXLL (where L is leucine, and X can be any amino acid) (11), termed the nuclear receptor interaction box or nuclear receptor signature motif (12–17). NR boxes and flanking residues are grouped into four classes depending on the amino acid residues present at the −1 and −2 positions upstream of the LXXLL motif. The first three classes were identified by a phage display approach, and the fourth class was identified following analysis of naturally occurring motifs among co-activators (11–18).

The α-actinins (ACTNs) are actin-binding proteins that are important for the maintenance of cytoskeletal structure and cell morphology (19). Four ACTNs have been identified, and among them ACTN2 and ACTN3 are expressed exclusively in muscle, while ACTN1 and ACTN4 are widely expressed (20). All ACTNs harbor several conserved functional domains including an N-terminal actin-binding domain that contains two highly conserved calponin homology (CH1 and CH2) sequences, a central domain consisting of four spectrin repeats (SRs), two EF hand calcium-binding domains, and a C-terminal calmodulin-like domain (21). Notably, although originally identified as an actin-binding protein, ACTN4 is localized in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (22, 23). Indeed, we have previously shown that ACTN4 interacts with and potentiates MEF2 transcription factors as well as estrogen receptor (ER) α and VDR (23, 24). The ability of ACTN4 to interact with and potentiate NR activity depends on an intact LXXLL motif present in ACTN4. Functionally, we demonstrated that knockdown of ACTN4 significantly decreased the ability of estrogen to induce the expression of ERα target genes. Together, these observations indicated that ACTN4 is an integral component in ERα-mediated transcriptional activation.

In this study, we dissected the mechanisms underlying the ability of ACTN4 and an alternatively spliced product called ACTN4 (Iso) to potentiate transcriptional activation. ACTN4 (Iso) lacks most of the CH1 domain and all of CH2, SR1, and SR2, resulting in a predominantly nuclear localization (23). We found that unlike full length ACTN4, ACTN4 (Iso) is capable of interacting with selective co-activators such as the p160 family members and PCAF. Unexpectedly, the sequence immediately C-terminal to LXXLL motif in ACTN4 is important for both its association with ERα and co-activators. Together, our data define a novel function for the LXXLL motif and its C-terminal flanking sequence in ACTN4.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

Expression plasmid CMX-HA-ACTN4 and its spliced isoform equivalent have been previously described (23). Point mutations in the ACTN4 (Iso) were generated using ACTN4 (Iso) cDNA as a template by site-directed PCR mutagenesis according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene). ERα (2–185) and ERα (186-ter) were generated by PCR using human ERα cDNA as a template and subsequently subcloned into the CMX-HA expression vector. For GST constructs, ACTN4 (Iso) cDNA was PCR-amplified and subcloned in the pGEX4T vector using standard cloning techniques. FLAG-pBabe-ACTN4 (Iso) was generated by PCR using HA-ACTN4 (Iso) as a template and subcloned into FLAG-pBabe vector. Expression plasmids for nuclear receptors, and reporter constructs were generous gifts from Dr. Ron Evans (The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Antibodies and Chemicals

Anti-ACTN4 antibody has been previously described (23, 24). Anti-HA-conjugated α-horseradish peroxidase was purchased from Roche Applied Science. α-VDR (C-20) and α-ERα (D-12) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. 1-(24R)-24,25-Dihydroxy-vitamin D3 (705861) and β-estradiol (E2, E8875) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Transient Transfection Reporter Assays

For reporter assays, CV-1 or MCF-7 cells in 48-well plates were co-transfected with equal amounts of either 100 ng of VDRE-TK-Luc or ERE-TK-Luc with or without pCMX-ACTN4 (full length) or pCMX-ACTN4 (Iso) along with 100 ng of pCMX-β-gal in 200 μl of Opti-MEM I using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The amount of DNA was kept constant by the addition of pCMX vector. After 5 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum, 50 units/ml penicillin G, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. After 24 h, medium was replaced with or without hormones as indicated. In all experiments, the cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, and luciferase and β-gal activities were measured according to the manufacturer's protocol using luciferase assay system (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized to the level of β-gal activity.

To test whether ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) harbor the intrinsic activation domain, we generated fusion proteins in which ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) were fused to yeast Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD). Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso) or Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) expression constructs were co-transfected with β-gal expression plasmid and a reporter construct harboring four copies of the Gal4 binding site (MH100) (28) for transient transfection assays.

Preparation of Purified Recombinant Human ERα Protein

Recombinant human ERα (181–552) protein was overexpressed from a pMCSG7 plasmid with an N-terminal His tag in bacteria. E2 was added to the medium during expression. The protein was isolated by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography, and the protein sequence was confirmed by mass spectrometry. Final homogenous dimeric protein was then eluted from size exclusion chromatography and analyzed by both denatured and native gels.

In Vitro Protein-Protein Interaction Assays

Glutathione S-transferase fusion protein GST-ACTN4 (Iso) was expressed in E. coli DH5a strain, affinity-purified, and immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. In vitro pulldown assays were carried out in which purified immobilized GST-ACTN4 (Iso), GST-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA), or GST-ACTN4 (Iso, M1/M2/M3) were incubated with whole cell extracts expressing nuclear receptors in the presence or absence of vitamin D3 (1 μm) or E2 (100 nm) for 1 h at 4 °C. For co-activator binding, immobilized, purified GST-ACTN4 (Iso), GST-ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102), and GST-ACTN4 (95–521) fusion proteins were incubated with whole cell lysates expressing co-activators. After extensive washing with NETN buffer (100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, and 1 mm dithiothreitol), SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to the beads, boiled, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed either with anti-HA-conjugated anti-horseradish peroxidase antibody (Roche Applied Science) or antibodies against nuclear receptors (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Co-immunoprecipitation

To detect the interaction between ACTN4 (Iso) and PCAF, HEK293 cells were grown on 10-cm plates and transfected with 10 μg of total DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 48 h, the cells were washed with 1× PBS. Whole cell lysates were prepared in NETN buffer along with protease inhibitors. Immunoprecipitations were carried out with anti-FLAG antibody M2 affinity gel (Sigma) for 4 h at 4 °C followed by Western blotting with α-HA-conjugated anti-horseradish peroxidase antibody (Roche Applied Science).

Transient Transfections and Immunoflourescence

MCF-7 cells were transfected either with wild-type or mutant ACTN4 (Iso) expression plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) followed by immunostaining with the indicated antibodies. Transfected cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and permeabilized in PBS with the addition of 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% goat serum for 10 min. The cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated in a PBS containing goat serum (10%) and Tween 20 solution (0.1%) (ABB) for 60 min. Incubation with primary antibodies was carried out for 120 min in ABB. The cells were washed three times in PBS, and the secondary antibodies were added for 60 min in the dark, at room temperature in ABB. Coverslips were mounted on slides using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (H-1200; Vector Laboratories, Inc.) The primary antibody used was purified a α-HA mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz). The secondary antibody used was from Molecular Probes (α-mouse Alexa Fluor 594).

Generation of Stable Cells Expressing FLAG-ACTN4 (Iso)

MCF-7 cells were stably transfected with FLAG-pBabe vector or FLAG-pBabe-ACTN4 (Iso). After transfection the stable cells were selected on puromycin (0.5 μg/ml) for 5 days. The stable cell lines were maintained in puromycin (0.25 μg/ml).

Transient Transfection Assays and qRT-PCR

MCF-7 cells were transfected with HA vector, HA-ACTN4 (Iso, WT), or HA-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) along with GFP expression plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). An aliquot of the cells was used for mRNA analyses by qRT-PCR. A second aliquot of the cells was subjected to Western blotting. For protein analyses, whole cell extracts were prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1× PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) along with the protease inhibitors. SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to the lysates, boiled, and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. In a typical experiment, the cells were treated with 10 nm E2 or ethanol as a vehicle control 48 h post-transfection for 24 h followed by RNA isolation or whole cell extract preparation. Total RNA was extracted from MCF-7 cells according to the manufacturer's protocol (Affymetrix). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Gene expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR using a real time PCR system (Bio-Rad) with the following primers: GAPDH, 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT-3′ and 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′; c-Myc, 5′-ATGAAAAGGCCCCCAAGGTAGTTAT-3′ and 5′-GCATTTGATCATGCATTTGAAACAA-3′; and pS2, 5′-GAGAACAAGGTGATCTGCGCCC-3′ and 5′-CCCACGAACGGTGTCGAAACA-3′.

Relative changes in gene expression were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Each value was representative of three replicates, and all experiments were repeated twice. To determine the effects of E2 on mRNA accumulation of ACTN4 (full length) and its spliced isoform, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated with 100 nm E2 and harvested at the indicated times followed by RNA isolation. Full length and isoform-specific primers were used for qRT-PCR to measure their mRNA expression.

Cell Proliferation Assays

For cell proliferation assays, MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-ACTN4 (Iso, WT) or (Iso, LXXAA) mutant expression plasmids. 48 h after transfection, the cells were trypsinized, and equal numbers of cells were seeded and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, 50 units/ml penicillin G, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Cell numbers were determined by a Cyquant cell proliferation assay kit (C7026) according to our published protocol (24). An aliquot of cells was also used to prepare whole cell lysates to examine expression levels of transfected HA-ACTN4 (Iso).

Molecular Modeling

A GRIP1 peptide from ERα (Protein Data Bank entry 3ERD) was used as a template (15). To build structural models for the ACTN4 peptide, the following two steps were used for virtual mutation. First, a rotamer library from SCWRL was used to predict the mutated side-chain conformations (26). Second, the final atom coordinates were subjected to energy optimization using the CHARMM force field (27), and the lowest energy conformation was finally selected.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student's t test.

RESULTS

ACTN4 (Iso) Potentiates NR-mediated Transcriptional Activation

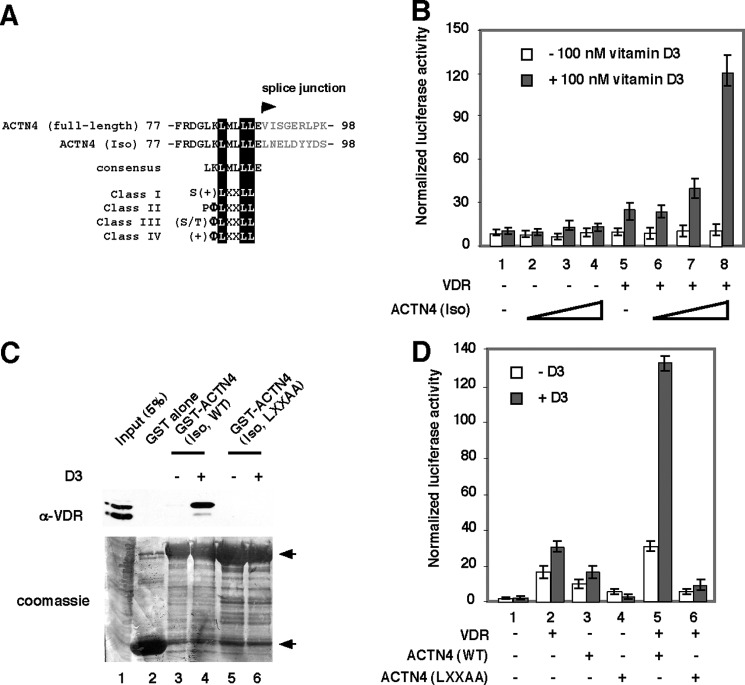

We have previous identified an alternatively spliced ACTN4 product ACTN4 (Iso) and shown that both the full length and the isoform are capable of potentiating MEF2 transcriptional activity (23). We have recently shown that ACTN4 (full length) is also capable of potentiating transcriptional activation by VDR and ERα and that knockdown of ACTN4 significantly compromised the ability of estrogen to induce ERα target genes (24). In addition to missing part of SR2, SR3, and SR4 because of exon exclusion, ACTN4 (Iso) harbors a putative LXXLL nuclear receptor interaction motif with distinct amino acid sequences C-terminal to the LXXLL motif when compared with ACTN4 (full length) (Fig. 1A). To test whether ACTN4 (Iso) modulates transcriptional activation by NRs, we carried out transient transfection reporter assays in CV1 cells using a reporter construct harboring a vitamin D3 response element (VDRE). Fig. 1B shows that in the absence of the VDR expression plasmid, ACTN4 (Iso) weakly activated VDRE reporter activity, regardless of vitamin D3 status. In the presence of VDR, ACTN4 was capable of activating VDRE reporter activity in a VDR dose-dependent manner. Most NR co-activators such as CBP/p300, PCAF, and the p160 family proteins utilize LXXLL receptor-interacting motifs to mediate their association with NRs. The nuclear receptor interaction box is required for transcriptional activation. To test whether ACTN4 (Iso) potentiates NR-mediated transcriptional activation by interacting with NRs through its LXXLL motif, we generated mutant ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) and examined its ability to interact with receptors by GST pulldown assays. As shown in Fig. 1C, we detected hormone-induced association of GST-ACTN4 (Iso, WT) with VDR. In contrast, GST or GST-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) mutant failed to bind VDR even in the presence of the vitamin D3 (Fig. 1C, lane 4 versus lane 6). We further determined the functional significance of the LXXLL motif by transient transfection reporter assays and found that ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) mutant dramatically lost the ability to potentiate transcriptional activation of a VDRE reporter (Fig. 1D). Together, these data show that ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with and potentiates VDR activity in a ligand-dependent manner.

FIGURE 1.

ACTN4 (Iso) potentiates transcriptional activation by nuclear hormone receptors. A, an alignment of the nuclear receptor interacting motif of ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso). The LXXLL motifs are highlighted. Note that the sequences C-terminal to LXXLL are different between ACTN4 (full length) and its isoform because of alternative splicing. The LXXLL motif is also aligned with the four known classes of co-activators (25). B, ACTN4 (Iso) activates VDR reporter activity. Transient transfection assays were carried out according to our published protocol (24). CV-1 cells were transfected with reporter construct harboring VDRE with or without ACTN4 (Iso) along with β-gal. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with or without 100 nm of vitamin D3. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-gal activity. Each data point represents the mean and S.D. of results from triplicates. C, GST-ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with VDR in GST pulldown assays. HEK293 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing VDR, and 48 h post-transfection the cells were lysed, and whole cell lysates were prepared and incubated with either GST alone or with GST-ACTN4 (Iso) in the presence or absence of 1 μm vitamin D3. Pulldown fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with anti-VDR antibodies (top panel). The bottom panel shows Coomassie staining of the GST fusion proteins. GST and GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion proteins are marked by arrows. D, ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) loses the ability to potentiate transcriptional activity mediated by VDR. Transient transfection assays were carried out as described for Fig. 1B except that both ACTN4 (Iso, WT) and ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) expression plasmids were used for the transfection.

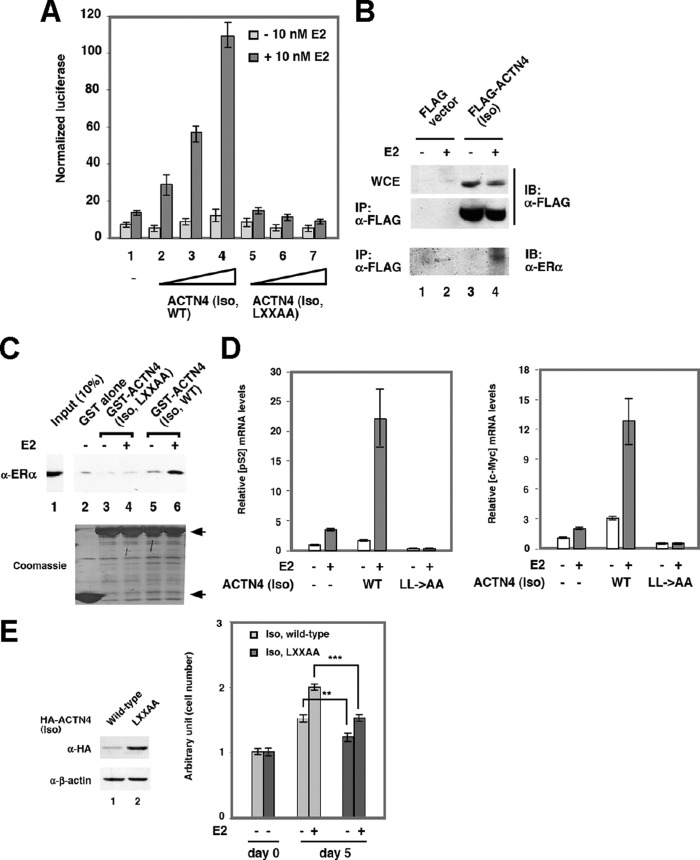

To test whether ACTN4 (Iso) can function as a co-activator for ERα-mediated transcriptional activation, we carried out transient transfection assays using a reporter construct harboring an estrogen response element (ERE). Fig. 2A shows that ACTN4 (Iso) was also capable of potentiating transcriptional activation by ERα in a dose-dependent manner. However, the LXXAA mutant failed to potentiate ERα activity (lanes 1–4 versus lanes 5–7). Indeed, overexpression of LXXAA partially inhibited basal and E2-induced reporter activity. The inability of ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) to potentiate transcriptional activation by NRs was not due to its aberrant subcellular localization (supplemental Fig. S1). We further demonstrated that E2 promoted the association between stably expressed FLAG-ACTN4 (Iso) and endogenous ERα (Fig. 2B) and that GST-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) failed to interact with ERα in a hormone-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). We further tested whether ACTN4 (Iso) was capable of inducing the expression of endogenous ERα target genes. MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector alone, ACTN4 (Iso), and ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) along with a GFP expression plasmid, and qRT-PCR was performed to determine the relative expression of selected ERα target genes. The expression levels of ACTN4 (Iso, WT) and ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) were relatively similar (supplemental Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 2D, in the presence of E2, a 4- and 3-fold increase in pS2 and c-Myc mRNA levels was observed in vector transfected cells, respectively. Transient overexpression of ACTN4 (Iso, WT) further induced pS2 and c-Myc mRNA levels by 5- and 3-fold, respectively. In contrast, overexpression of ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) failed to potentiate E2-induced mRNA expression level of pS2 and c-Myc, indicating that ACTN4 (Iso) potentiates E2-induced selected ERα target genes in MCF-7 cells and that the LXXLL motif is critical for this activity. Moreover, MCF-7 cells ectopically transfected with the wild-type but not with the mutant ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) exhibited a higher proliferation rate (Fig. 2E, right panel). These data indicated that the LXXLL motif is critical for the ability of ACTN4 (Iso) to potentiate E2-dependent activation of ERα target genes and proliferation (Fig. 2E). Altogether, these data suggest that similarly to ACTN4 (full length) (24), the ability of ACTN4 (Iso) to interact with and potentiate transcriptional activation of VDR and ERα target genes requires the LXXLL motif.

FIGURE 2.

ACTN4 (Iso) potentiates ERα transcriptional activity. A, the LXXLL motif is critical for the ability of ACTN4 (Iso) to potentiate transcription from an ERE reporter. MCF-7 cells were transfected with a reporter plasmid harboring an ERE element, an expression plasmid for ACTN4 (Iso) or ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) and β-gal. The cells were treated with or without 10 nm of E2, and luciferase activities were determined and normalized to β-gal activities. Each data point represents the mean and S.D. of results from triplicates. B, MCF-7 cells stably expressing FLAG vector alone (lanes 1 and 2) or FLAG-ACTN4 (Iso) (lanes 3 and 4) were grown in stripped serum for 12 h followed by ethanol (lanes 1 and 3) or E2 (lanes 2 and 4) treatment for an additional 12 h. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG or anti-ERα antibodies. C, the LXXLL motif is required for ACTN4 (Iso) and ERα association. HEK 293 cells were transfected with expression plasmid for ERα, and whole cell lysates were incubated with bacterially expressed GST-ACTN4 (Iso) or with GST-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) in the presence or absence of 100 nm of E2 for 1 h. Pulldown fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with α-ERα antibodies (top panel). Coomassie Blue staining is shown to demonstrate equal loading for GST beads (bottom panel). Lane 1 shows 10% of the input used for the pulldown assays. GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion proteins are marked by arrows. D, ACTN4 (Iso) enhances the expression of endogenous ERα target genes. MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector alone, ACTN4 Iso (WT), and ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) mutant along with a GFP expression plasmid. The GFP plasmid was used for normalization. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with charcoal stripped serum containing medium, and after 48 h the cells were treated with or without 10 nm of E2 for an additional 48 h. An aliquot of the samples were used to prepare total cell lysates for Western blotting (supplemental Fig. S2), and another aliquot was used to extract RNA. Total RNA was used to prepare cDNA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Real time qRT-PCR was carried out to analyze the changes in mRNA abundance of ERα target genes including pS2 (left panel) and c-Myc (right panel) after overexpression of ACTN4 (Iso) and ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA). The mRNA levels of target genes were normalized to GAPDH. The mRNA expression level of pS2 and c-Myc in MCF-7 cells overexpressing vector alone treated with vehicle was set to 1. E, wild-type ACTN4 (Iso) is more potent in increasing E2-mediated MCF-7 cell proliferation than the ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) mutant. The left panel shows the expression levels of transfected wild-type and mutant ACTN4 (Iso) at day 0. The right panel shows the cell proliferation of wild-type and mutant HA-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) transfected MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cell proliferation assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The statistical comparison of data is presented (** or ***). **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.0001. IP, immunoprecipitation.

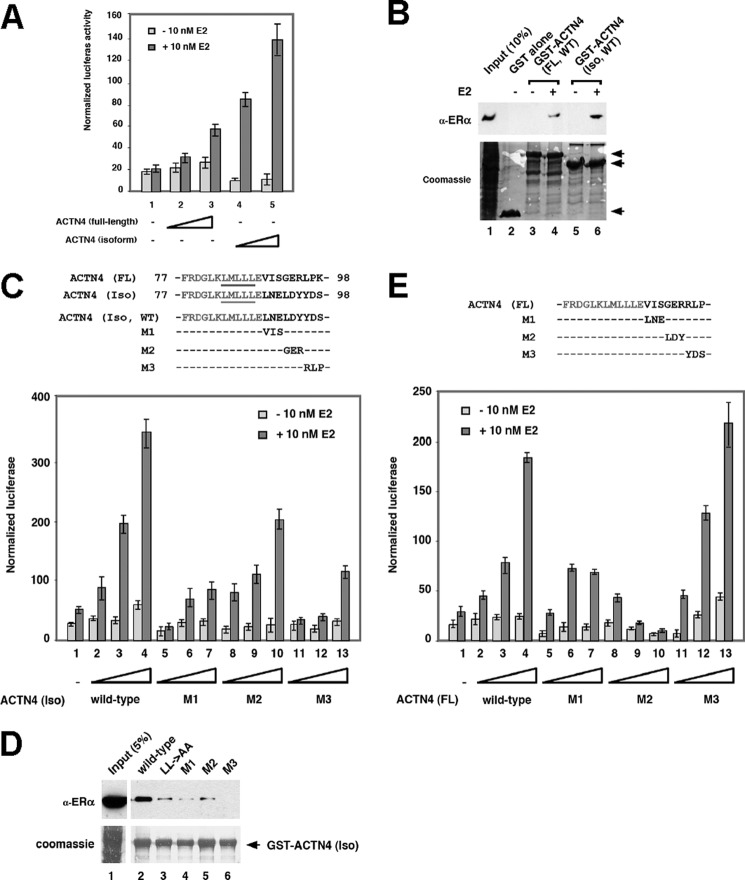

Because both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) harbor LXXLL motifs, we compared their ability to stimulate transcription regulated by ERα. Fig. 3A shows that both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) stimulate ERE transcriptional activity in a dosage-dependent manner (columns 1–5); however, ACTN4 (Iso) was more potent as compared with ACTN4 (full length) in inducing the transcription mediated by ERα (columns 2 and 3 versus columns 4 and 5). To elucidate the mechanism underlying the differential transcriptional regulation mediated by ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso), we analyzed the ability of ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) to interact with ERα. As shown in Fig. 3B, the interaction with ACTN4 (Iso) with ERα was slightly stronger than ACTN4 (full length) (column 4 versus column 6). Although the sequences N-terminal to the LXXLL receptor interacting motifs of ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) are identical, the sequences C-terminal to the LXXLL motif are distinct (Fig. 3C, top panel). To dissect the molecular basis of the association between ACTN4 (full length) or ACTN4 (Iso) and nuclear receptors, we replaced three amino acids of the sequences C-terminal to the LXXLL motif with that of the full-length protein and examined their ability to potentiate transcription. We found that ACTN4 (Iso, WT) potently activated an ERE reporter construct, whereas all three triple mutants (M1, M2, and M3) significantly lost their ability to activate reporter activity, and among them, the M1 mutant exhibited the most severe defect (Fig. 3C, bottom panel). Immunofluorescence microscopy indicated that these mutants displayed subcellular localization similar to that of the wild-type ACTN4 (Iso) protein (supplemental Fig. S3A). By contrast, these mutants still interacted with HDAC7 similarly to that of the wild-type protein (supplemental Fig. S4). Because the HDAC7 interaction domain is at the C-terminal region of ACTN4 (23), and the LXXLL motif is in the N terminus of ACTN4 (Fig. 2), these data indicate that these mutations did not alter global protein folding. Because these ACTN4 (Iso) downstream mutants were defective in activating an ERE reporter, we speculated that they might also be defective in their abilities to interact with ERα. To address this question, we generated GST-ACTN4 (Iso) mutant fusion proteins and carried out GST pulldown assays. As shown in Fig. 3D, all three ACTN4 mutants significantly lost their ability to interact with ERα. These data indicate that the C-terminal sequences to the LXXLL motif are also important for the interaction of ACTN4 (Iso) with ERα. Similar approaches were used to examine the sequences important for transcriptional activation mediated by ERα in ACTN4 (full length). We found that ACTN4 (full length) mutants M1 and M2 that were replaced by the corresponding amino acids in ACTN4 (Iso) still lost their ability to activate transcription by ERα (Fig. 3E). Immunofluorescence microscopy indicated that these mutants and the LXXAA mutant exhibited subcellular distribution similar to that of the wild-type ACTN4 (full length) protein (supplemental Fig. S3B). Together, these data indicate that sequences C-terminal to the LXXLL motif regulate the ability of ACTN4 to potentiate ERα binding and ERE reporter activity.

FIGURE 3.

The effect of the sequences downstream of the LXXLL motif on ERE reporter activity. A, ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) potentiate the transcriptional activation mediated by ERα. MCF-7 cells were transfected with varying amounts of ACTN4 (Iso) or ACTN4 (full length) as indicated in the figure along with a reporter construct bearing an ERE and β-gal. Transient transfection assays were carried out as described for Fig. 2A. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized to β-gal activity. Each data point represents the mean and S.D. of results from triplicates. B, ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) interact with ERα in vitro. Immobilized GST-ACTN4 (Iso) or GST-ACTN4 (full length) were incubated with whole cell lysates prepared from HEK293 cells expressing ERα. Pulldown fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with α-ER antibodies (top panel). The amount of GST fusion proteins is shown at the bottom panel as visualized by Coomassie Blue staining. GST, GST-ACTN4 (full length), and GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion proteins are marked by arrows. 5% of input is shown in lane 1. C, effect of wild-type and mutant ACTN4 (Iso) on ERα reporter activity. An alignment of the receptor interacting motif LXXLL in ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) is shown along with the substitutions described in the text (top panel). MCF-7 cells were transfected with varying amounts of ACTN4 (Iso) or the mutants indicated in the figure along with a reporter construct bearing an ERE and β-gal. Transient transfection assays were carried out as described for Fig. 2A. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized to β-gal activity. Each data point represents the mean and S.D. of results from triplicates (bottom panel). D, the ACTN4 (Iso) mutants fail to bind ERα. Immobilized GST-ACTN4 (Iso), GST-ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA), GST-ACTN4 (Iso, M1), GST-ACTN4 (Iso, M2), or GST-ACTN4 (Iso, M3) were incubated with whole cell lysates prepared from HEK293 cells overexpressing ERα. Pulldown fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with α-ER antibodies (top panel). Coomassie Blue staining is shown at the bottom panel demonstrating the equal expression of GST beads. 5% of input is shown in lane 1. GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion protein is marked by an arrow. E, effect of wild-type and mutant ACTN4 (full length) on the transcription mediated by ERα. Top panel, a sequence alignment showing the mutants made in ACTN4 (full length). Bottom panel, transient transfection assays were carried out as described for Fig. 2A, except that MCF-7 cells were transfected with ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (full length) mutants shown above. FL, full length.

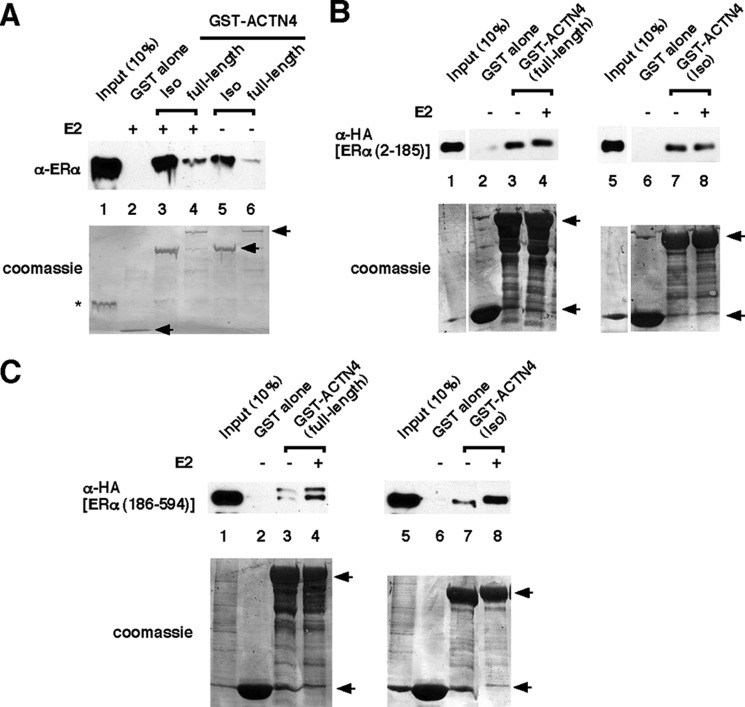

To determine whether the interaction between ACTN4 and ERα is direct, we expressed and purified recombinant ERα (181–552) used for GST pulldown assays. We found that although both GST-ACTN4 (Iso) and GST-ACTN4 (full length) pulled down ERα (181–552), the isoform interacts with ERα stronger than the full-length protein (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, these interactions were enhanced in the presence of E2.

FIGURE 4.

Mapping of ACTN4 interacting domains. A, immobilized purified GST-ACTN4 (Iso) and GST-ACTN4 (full length) fusion proteins interact with purified recombinant ERα (181–552). GST pulldown assays were performed as described for Fig. 3B except that purified recombinant ERα protein was used. Note that both GST-ACTN4 fusion proteins were capable of pulling down recombinant ERα (181–552) even in the absence of E2. This is likely due to the presence of E2-bound ERα from incomplete removal of E2 during purification. The asterisk marks the purified ERα. B and C, GST (lanes 2 and 6), GST-ACTN4 (full length) (lanes 3 and 4), or GST-ACTN4 (Iso) (lanes 7 and 8) fusion proteins were immobilized and incubated with extracts expressing HA-ERα (2–185) (B) or HA-ERα (186-ter) (C). Pulldown fractions were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. The lower panel shows Coomassie staining of the GST fusion proteins. GST, GST-ACTN4 (Iso), and GST-ACTN4 (full length) fusion proteins are marked by arrows.

To further dissect the molecular basis of the interaction between ACTN4 and ERα, we generated HA-tagged plasmids expressing N- or C-terminal ERα fragments harboring amino acids 2–185 or 186–594, respectively. GST pulldown assays were used to determine the association between ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) and the N- or C-terminal fragments of ERα in the absence or presence of E2. Fig. 4B shows that both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) interact with the N terminus of ERα in a ligand-independent manner. However, E2 was capable of enhancing the association of the ERα C-terminal fragment, which harbors a ligand-binding domain, with both ACTN4 isoforms (Fig. 4C).

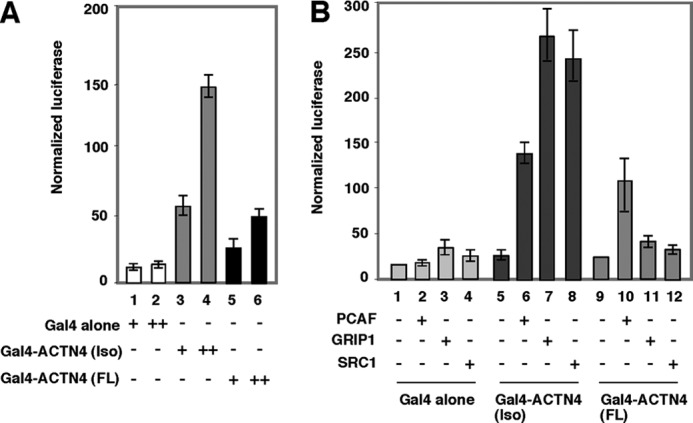

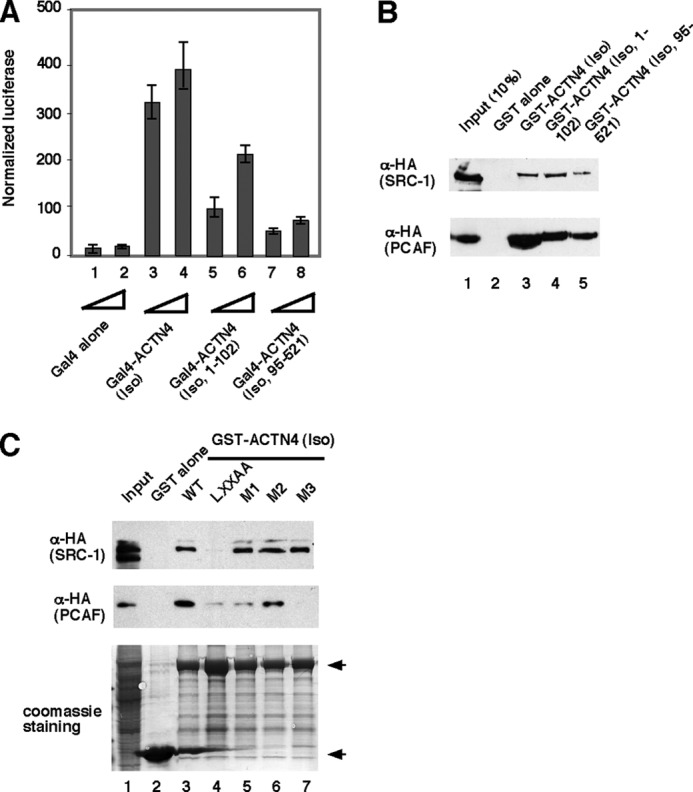

To further understand the molecular mechanism underlying ACTN4 (Iso) co-activation activity, we used transient transfection assays to test whether ACTN4 is able to activate transcription when tethered to a promoter region. We generated proteins in which ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) were fused to yeast Gal4 DBD. Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso) or Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) expression constructs were co-transfected with a reporter construct harboring four copies of the Gal4 binding site (MH100) (28). Fig. 5A shows that Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso) potently activated basal transcription activity, whereas Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) weakly activated the reporter. Because neither ACTN4 (full length) nor ACTN4 (Iso) harbor motifs known to modify histones or remodel chromatin, we hypothesized that ACTN4 may activate transcription through an interaction with other co-activators. To test this, we first examined whether p160 family members or PCAF were able to potentiate reporter activity of MH100 reporter gene by Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) or ACTN4 (Iso). Because these co-activators harbor intrinsic transcriptional activation domains, an interaction between these co-activators and ACTN4 would further enhance reporter activity. We found that coexpression of both the p160 co-activators and PCAF significantly enhanced the ability of ACTN4 (Iso) to activate reporter activity (Fig. 5B). However, only PCAF was capable of weakly activating Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) activity. In summary, these results suggest that the potent activation function of ACTN4 (Iso) may be attributed to its association with co-activators.

FIGURE 5.

ACTN4 harbors an intrinsic transcriptional activation domain. A, Gal4-ACTN4 activates basal transcription. CV-1 cells were transfected with MH100 encoding luciferase controlled by Gal4 response elements and expression plasmids encoding Gal4-DBD or Gal4-DBD fused to ACTN4 (full length) or to ACTN4 (Iso) alone with CMX-β-gal as an internal control. Transient transfection reporter assays were performed as described for Fig. 2A. B, co-activators potentiate transcriptional activity of Gal4-ACTN4. CV-1 cells were transfected with Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) and Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso) along with expression plasmids encoding co-activators GRIP1, PCAF, and SRC-1. Transient transfections were carried out as described for Fig. 2A. Note that GRIP1 and SRC-1 could not potentiate Gal4-ACTN4 (full length) activity but did activate reporter activity mediated by Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso). Each data point represents the mean and S.D. of results from triplicates. FL, full length.

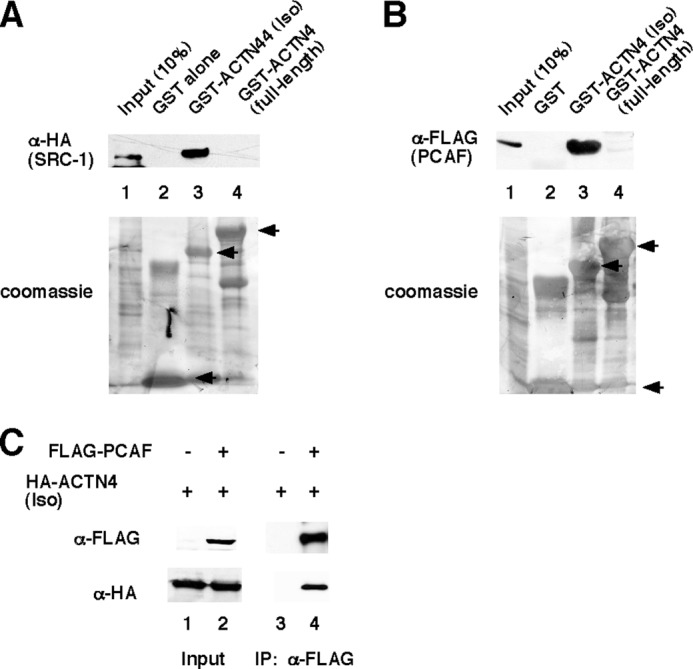

To determine whether ACTN4 physically interacts with co-activators, we first carried out GST pulldown assays. Immobilized, purified GST-ACTN4 (Iso) and GST-ACTN4 (full length) fusion proteins were incubated with whole cell lysates overexpressing p160 co-activator family members or PCAF. We found that GST-ACTN4 (Iso) bound efficiently to all three p160 co-activators (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S5), as well as PCAF (Fig. 6B). In contrast, GST-ACTN4 (full length) did not interact with either SRC-1 or with PCAF (Fig. 6, A and B, lane 4). To validate the interaction in mammalian cells, FLAG-PCAF and HA-ACTN4 (Iso) were coexpressed in HEK293 cells, and immunoprecipitations were carried out using α-FLAG antibodies followed by Western blotting. We found that ACTN4 (Iso) associates robustly with PCAF (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with co-activators in vitro and in vivo. A and B, ACTN4 interacts with co-activator SRC-1 and PCAF in vitro. HEK293 cells were transfected with either HA-SRC-1 or FLAG-PCAF expression plasmids. Whole cell lysates were prepared and incubated with either GST-ACTN4 (Iso) and or GST-ACTN4 (full length) for 1 h. Pulldown fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with either α-HA and α-FLAG antibodies. Lane 1 shows 10% input. The lower panel shows Coomassie staining of the GST fusion proteins. GST, GST-ACTN4 (Iso), and GST-ACTN4 (full length) fusion proteins are marked by arrows. C, ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with PCAF. Immunoprecipitation experiments were carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Briefly, FLAG-PCAF and HA-ACTN4 (Iso) constructs were used for transfection, and α-FLAG antibodies were used for immunoprecipitations. Sample buffer was added to immunoprecipitated fractions followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with α-HA and α-FLAG antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitation.

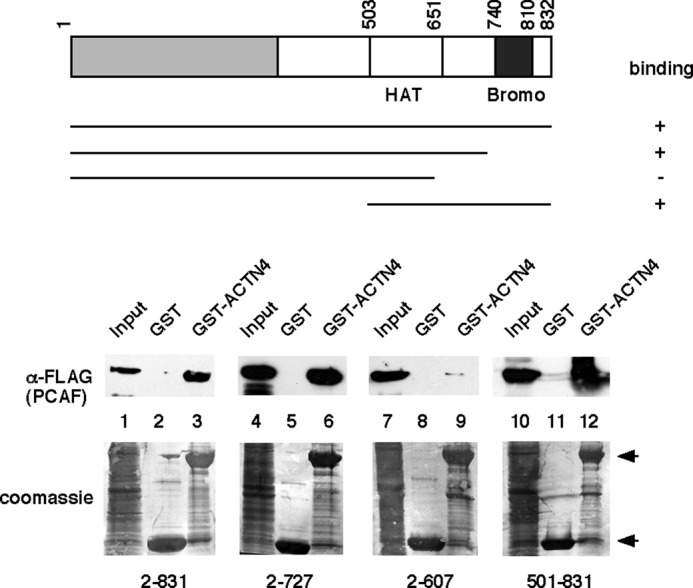

PCAF harbors a protein acetylation enzymatic domain (histone acetyltransferase (HAT)) and a bromodomain that binds acetylated proteins. We further explored the molecular basis of the interaction between ACTN4 (Iso) and PCAF. We carried out GST pulldown assays using HEK293 whole cell lysates expressing different fragment of PCAF and GST-ACTN4 (Iso, WT). As shown in Fig. 7, ACTN4 (Iso) interacted with amino acids 501–831 and only modestly with amino acids 2–607, suggesting that the interaction domain of ACTN4 (Iso) in PCAF lies within HAT domain. To find out which region in ACTN4 (Iso) interacted with co-activators. CV-1 cells were transfected with Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso), Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102), and Gal4-ACTN4 (95–521) along with the Gal4 reporter construct MH100. We found that both Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102) and Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso, 95–521) showed transcriptional activation, although Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102) was more potent (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, we tested whether these two fragments interact with co-activators by GST pulldown assays. As shown in Fig. 8B, both these two independent activation domains were capable of interacting with co-activators SRC-1 and PCAF, although again, ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102) was stronger. We conclude that there are two independent activation domains in ACTN4 (Iso).

FIGURE 7.

Amino acids of 501–727 of PCAF are essential for ACTN4 association. Different fragments of FLAG-PCAF were expressed in HEK293 cells. Lysates were prepared, and pulldown assays were carried out by incubating the lysates with bacterially expressed GST-ACTN4 (Iso) followed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. Inputs for different pulldowns are shown in lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10. Bottom panel, Coomassie Blue staining. GST and GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion proteins are marked by arrows. Bromo, bromodomain.

FIGURE 8.

ACTN4 (Iso) harbors two independent activation domains. A, CV-1 cells were transfected with MH100 harboring Gal4-responsive elements along with expression plasmids encoding Gal4-DBD or Gal4-DBD (Iso) or Gal4-DBD (Iso, 1–102) or Gal4-DBD (Iso, 95–521). Transient transfection reporter assays were performed as described for Fig. 2A. B, both ACTN4 (Iso) activation domains interact with co-activators. HEK293 cells overexpressing HA-SRC-1 and HA-PCAF were incubated with immobilized GST-ACTN4 (Iso), GST-ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102), and ACTN4 (95–521) for 1 h. Pulldown fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with α-HA antibodies. C, the LXXLL motif and its flanking sequences are critical for co-activator binding. Top panel, immobilized, purified wild-type or mutant GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion proteins were incubated with cell lysates expressing HA-SRC-1 or HA-PCAF, and pulldown was carried out as described for Fig. 7, followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. Bottom panel, Coomassie Blue staining is shown. GST and GST-ACTN4 (Iso) fusion proteins are marked by arrows. 10 and 5% of input are shown for SRC-1 and PCAF, respectively.

The observation that ACTN4 (Iso, 1–102) is capable of interacting with SRC-1 and PCAF raised the question of whether the C-terminal sequences to the extended LXXLL motif in the ACTN4 (Iso) was critical for this binding activity. Amino acids 1–95 of ACTN4 (Iso) and ACTN4 (full length) are identical, but amino acids 96–102 are unique to each isoform. To test this possibility, we used ACTN4 (Iso) mutants generated in Fig. 3 and carried out GST pulldown assays. Fig. 8C shows that surprisingly, the ACTN4 (LXXAA) mutant significantly lost its ability to bind co-activators SRC-1 and PCAF (Fig. 8A, columns 3 and 4). Furthermore, M1 and M3 mutants lost their ability to interact with PCAF. Taken together, these data indicate that flanking sequences of the extended LXXLL motif are critical for ACTN4 (Iso) co-activator binding.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have suggested that actin and actin-binding proteins play an important role in transcription in addition to their function as cytoskeleton proteins (29, 30). Actin and actin-related proteins have been shown to be present in complexes associated with transcriptional machinery (31, 32). We have also previously shown that both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) are capable of potentiating activity of MEF2 transcription factors (23) and that ACTN4 (full length) regulates nuclear receptor-mediated transcription by antagonizing HDAC7 function (24). Here we report a distinct role played by ACTN4 (Iso) in nuclear receptor-mediated transcription that is due to its ability to bind with both NRs and co-activators. We have dissected the mechanisms by which ACTN4 (Iso) potentiates transcriptional activation mediated by ERα. The major novel findings from our study include: 1) ACTN4 (Iso) is a more potent transcriptional co-activator of nuclear hormone receptors than ACTN4 (full length); 2) both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) directly interact with ERα, but ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with ERα somewhat more stronger than ACTN4 (full length); 3) both ACTN4 (Iso) and ACTN4 (full length) activate basal transcription when tethered to a promoter region; 4) ACTN4 (Iso) harbors two independent activation domains; 5) although ACTN4 (Iso) interacts strongly with co-activators, ACTN4 (full length) associates weakly with co-activators; 6) ACTN4 (Iso) has an unusual extended nuclear interacting motif, LXXLL, which is critical for ACTN4 (Iso) to interact with and potentiates transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors; and 7) the HAT domain of PCAF is essential for its interaction with ACTN4 (Iso). Taken together, we have defined ACTN4 (Iso) as a potent transcriptional co-activator for nuclear hormone receptors.

We have shown that the LXXLL motif present in both ACTN4 (Iso) and ACTN4 (full length) plays an important role in transcriptional regulation mediated by nuclear receptors (Ref. 24 and Fig. 1A). Mutations of LXXLL to LXXAA in ACTN4 (Iso) abolished its physical interaction with NRs and its ability to regulate transcriptional activation mediated by NRs (Figs. 1. B–D, and 2, A and B). Additionally, we show that ectopic overexpression of ACTN4 (Iso, WT) further enhances hormonal induction of endogenous ERα target genes (Fig. 2C). Finally, MCF-7 cells transfected with ACTN4 (Iso) grew better than those transfected with ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA) mutant regardless of E2 treatment, although the difference in proliferation rate in E2-treated cells is significantly larger than the untreated group (Fig. 2D). These data indicate that ACTN4 may play a role in both E2-dependent and -independent growth. We have also observed a transient induction in mRNA levels for both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) in E2-treated MCF-7 cells, but not in ERα-negative MDAMB-231 breast cancer cells (supplemental Fig. S6). These data suggest that E2-induced ACTN4 mRNA expression contributes to its ability to modulate transcription and cell proliferation in ERα-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Molecular Determinants Regulating NR-mediated Transcriptional Activity

We have previously demonstrated that MCF-7 breast cancer cells express both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) mRNAs, although the full-length protein is expressed at a much higher level (23). We showed that knockdown of ACTN4 decreases MCF-7 cell proliferation, ERE-driven reporter activity, and expression of ERα target genes, pS2 and c-Myc (24). Because there is so little sequence unique to ACTN4 (Iso), it was not possible to selectively knock it down. However, exogenous overexpression of ACTN4 (full length) (24) or ACTN4 (Iso) significantly induced the pS2 and c-Myc mRNA level (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, ACTN4 (Iso) overexpressed MCF-7 cells proliferated more robustly than LXXAA mutant-expressing cells (Fig. 2D). We have previously shown that endogenous ACTN4 is recruited to pS2 promoter in a ligand-dependent manner (24). Although we attempted to generate full-length and isoform-specific peptide antibodies, this effort was not successful. As such, we do not know whether ACTN4 (full length) or ACTN4 (Iso) is predominantly recruited to this promoter. Our in vitro pulldown assays show that ACTN4 (Iso) binds ERα more tightly than the full-length protein (Fig. 3B). Consistent with this observation, substitution of the residues C-terminal to the LXXLL motif in ACTN4 (Iso) with the corresponding residues in ACTN4 (full length) reduced the ability of ACTN4 (Iso) to bind to ERα and to activate transcription (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, whereas M1, M2, and M3 mutants of ACTN4 (Iso) were defective in binding PCAF (Fig. 8C), these mutants still bound SRC-1 with the same affinity as the wild-type protein. These data indicate that different co-activators interact with ACTN4 (Iso) through distinct surfaces. However, the LXXLL mutant, ACTN4 (Iso, LXXAA), completely lost its ability to bind NRs or co-activators and its ability to potentiate transcription activation by NRs. Domain mapping studies have demonstrated that ACTN4 binds to both N- and C-terminal fragments of ERα. Similar to several other co-activators, ACTN4 interacts with ERα N-terminal fragment independent of the presence of E2. However, E2 induced an association between ACTN4 and the ERα C-terminal domain. Thus, ACTN4 joins a group of co-activators harboring bifunctional nuclear receptor interacting domains. Based on our data, we built a structural models of ACTN4 docking with ERα, using the published ERα:GRIP1 peptide co-crystal structure as a template (15). We found that our modeled ACTN4 LXXLL-containing peptides fit well with the ERα ligand-binding pocket and the activated helix 12, suggesting that it is likely that ACTN4 binds to ERα in a manner similar to the GRIP1 LXXLL-containing peptide (Fig. 9). Interestingly, it was previously shown that the second LXXLL motif in NCoA1 (SRC-1/ACTR/PCIP) is responsible for NR binding, whereas the fourth LXXLL motif is important for CBP/p300 recruitment (12). Therefore, the single LXXLL motif in ACTN4 (Iso) represents a novel motif that not only interacts with several co-activators but also binds NRs in a ligand-dependent manner.

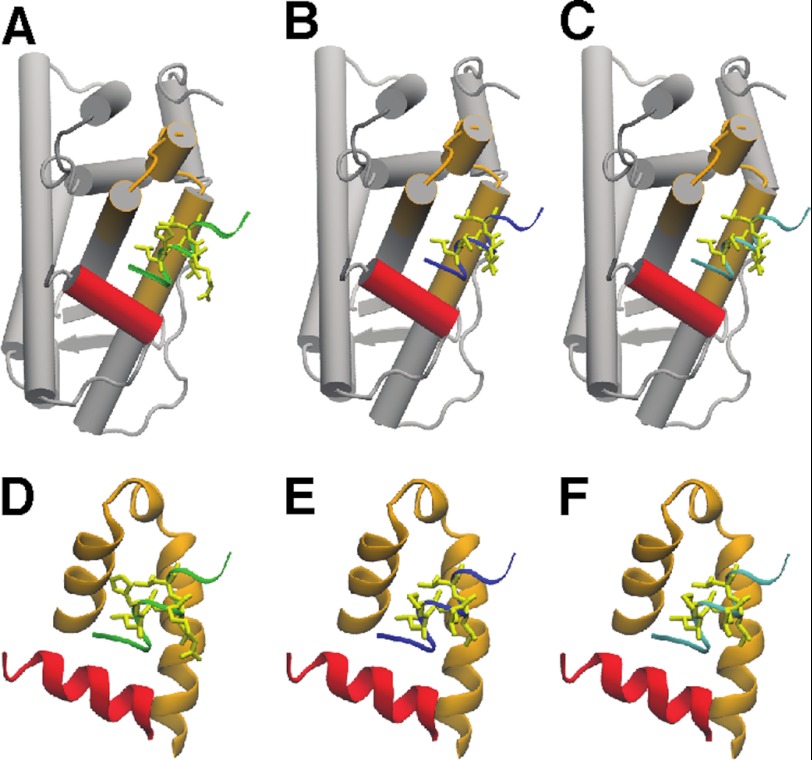

FIGURE 9.

Structure models of ACTN LXXLL-containing peptides interacting with synthetic E2-bound ligand-binding domain of ERα. A–C, cartoon illustration of the interaction between ligand-binding domain and co-activating peptides. A co-crystal structure of the LXXLL-containing peptide from GRIP1 NR box II (NH2-KHKILHRLLQD-CO2H) and E2-bound ERα ligand-binding domain (A) (15) was used as a template to model the structure between the LXXLL-containing peptides from ACTN (Iso) (middle, NH2-FRDGLKLMLLLEL-CO2H) (B) or full length ACTN4 (right, NH2-FRDGLKLMLLLEV-CO2H) (C). D–F, an enlarged view of the interaction between the AF-2 activation pocket and the peptides. H12 is highlighted in red, and the AF-2 activation pocket is highlighted in orange. The LXXLL-containing peptides of GRIP1 (D), ACTN4 (Iso) (E), and ACTN4 (full length) (F) are highlighted in green (left), blue (middle), and cyan (right), respectively.

Distinct Co-activation Activity

Both ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) possess a LXXLL receptor interaction motif. However, the mechanisms by which these two isoform activate ERα-mediated transcription are distinct. First, based on the expression levels of ACTN4 and the potency of co-activation, it is clear that ACTN4 (Iso) is a more potent ERα co-activator than ACTN4 (full length) when both are expressed at the same level. Several reasons may account for ACTN4 (Iso) being a more potent co-activator for transcription mediated by ERα. ACTN4 (full length) is predominantly cytoplasmic, whereas ACTN4 (Iso) is primarily nuclear (Ref. 23 and supplemental Fig. S1). In fact, deletion of the actin-binding domain of ACTN4 (full length) leads to a predominantly nuclear distribution and higher co-activation activity (data not shown). Second, ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with ERα slightly better than the full-length protein. Third, ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with higher affinity with co-activators than ACTN4 (full length). The interaction between ACTN4 (Iso) and co-activators is specific because they show relatively no or weak interactions with ACTN4 (full length). These data argue that the ability of ACTN4 (Iso) and ACTN4 (full length) to activate ERα activity absolutely requires a high affinity association with ERα. Our data suggest that when tethered to the promoter region, Gal4-ACTN4 (Iso) possesses potent transcriptional activity (Fig. 5), and this activity correlates with its ability to associate with co-activators including PCAF and p160 family members (Fig. 8). Indeed, ACTN4 (full length) is a weaker co-activator and only binds weakly to most co-activators. Thus, our data suggest that ACTN4 (Iso) interacts with GRIP1 and PCAF to regulate transcription mediated by ERα.

It is possible that another difference between ACTN4 (full length) and ACTN4 (Iso) is that the latter may be substrate for a HAT enzyme. The GCN5 and PCAF have been shown to acetylate several transcription factors directly in addition to their global and gene-specific acetylation of histone proteins (33–36). The acetylation of non-histone proteins such as chromatin remodelers, sequence-specific transcription factors, transcriptional activators, and nuclear receptor cofactors can affect nuclear localization, inhibition of nuclear export, enhanced DNA binding, stimulation of transcription, or enhanced co-activator association (37, 38). However, whether HAT activity of PCAF is essential for ACTN4 (Iso) to enhance its transcriptional activity mediated by nuclear hormone receptor is under investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Samols for comments on the manuscript. We also thank Drs. Ron Evans, Michael Stallcup, and Hongwu Chen for providing p160 co-activator expression plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 DK078965 and HL093269 (to H.-Y. K.) and P30 CA43703-12. This work was also supported by American Cancer Society-Institutional Research Grant ACS IRG-91-022-15 (to S. Y.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- NR

- nuclear hormone receptor

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- ACTN

- α-actinin

- VDR

- vitamin D receptor

- CBP

- cAMP-responsive element-binding protein

- PCAF

- p300/CBP-associated factor

- SRC-1

- steroid receptor co-activator 1

- GRIP1

- glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1

- ACTR

- activator of thyroid and retinoic acid receptor

- SR

- spectrin repeat

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- qRT

- quantitative RT

- VDRE

- vitamin D3 response element

- ERE

- estrogen response element.

REFERENCES

- 1. Beato M., Herrlich P., Schütz G. (1995) Steroid hormone receptors. Many actors in search of a plot. Cell 83, 851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mangelsdorf D. J., Thummel C., Beato M., Herrlich P., Schütz G., Umesono K., Blumberg B., Kastner P., Mark M., Chambon P., Evans R. M. (1995) The nuclear receptor superfamily. The second decade. Cell 83, 835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. (1994) Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 451–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee Y. H., Campbell H. D., Stallcup M. R. (2004) Developmentally essential protein flightless I is a nuclear receptor coactivator with actin binding activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2103–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (2000) The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 14, 121–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heinlein C. A., Chang C. (2002) Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators. An overview. Endocr. Rev. 23, 175–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolf I. M., Heitzer M. D., Grubisha M., DeFranco D. B. (2008) Coactivators and nuclear receptor transactivation. J. Cell. Biochem. 104, 1580–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gehin M., Mark M., Dennefeld C., Dierich A., Gronemeyer H., Chambon P. (2002) The function of TIF2/GRIP1 in mouse reproduction is distinct from those of SRC-1 and p/CIP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5923–5937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu J., Qiu Y., DeMayo F. J., Tsai S. Y., Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. (1998) Partial hormone resistance in mice with disruption of the steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) gene. Science 279, 1922–1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu J., Liao L., Ning G., Yoshida-Komiya H., Deng C., O'Malley B. W. (2000) The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6379–6384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heery D. M., Kalkhoven E., Hoare S., Parker M. G. (1997) A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature 387, 733–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McInerney E. M., Rose D. W., Flynn S. E., Westin S., Mullen T. M., Krones A., Inostroza J., Torchia J., Nolte R. T., Assa-Munt N., Milburn M. V., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (1998) Determinants of coactivator LXXLL motif specificity in nuclear receptor transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 12, 3357–3368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Darimont B. D., Wagner R. L., Apriletti J. W., Stallcup M. R., Kushner P. J., Baxter J. D., Fletterick R. J., Yamamoto K. R. (1998) Structure and specificity of nuclear receptor-coactivator interactions. Genes Dev. 12, 3343–3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nolte R. T., Wisely G. B., Westin S., Cobb J. E., Lambert M. H., Kurokawa R., Rosenfeld M. G., Willson T. M., Glass C. K., Milburn M. V. (1998) Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature 395, 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shiau A. K., Barstad D., Loria P. M., Cheng L., Kushner P. J., Agard D. A., Greene G. L. (1998) The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell 95, 927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perissi V., Rosenfeld M. G. (2005) Controlling nuclear receptors. The circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 542–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aoyagi S., Archer T. K. (2008) Nicotinamide uncouples hormone-dependent chromatin remodeling from transcription complex assembly. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 30–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Francis G. A., Fayard E., Picard F., Auwerx J. (2003) Nuclear receptors and the control of metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 261–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Djinovic-Carugo K., Gautel M., Ylänne J., Young P. (2002) The spectrin repeat. A structural platform for cytoskeletal protein assemblies. FEBS Lett. 513, 119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Otey C. A., Carpen O. (2004) α-Actinin revisited. A fresh look at an old player. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 58, 104–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Djinović-Carugo K., Young P., Gautel M., Saraste M. (1999) Structure of the α-actinin rod. Molecular basis for cross-linking of actin filaments. Cell 98, 537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Honda K., Yamada T., Endo R., Ino Y., Gotoh M., Tsuda H., Yamada Y., Chiba H., Hirohashi S. (1998) Actinin-4, a novel actin-bundling protein associated with cell motility and cancer invasion. J. Cell Biol. 140, 1383–1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chakraborty S., Reineke E. L., Lam M., Li X., Liu Y., Gao C., Khurana S., Kao H. Y. (2006) α-Actinin 4 potentiates myocyte enhancer factor-2 transcription activity by antagonizing histone deacetylase 7. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35070–35080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khurana S., Chakraborty S., Cheng X., Su Y. T., Kao H. Y. (2011) The actin-binding protein, actinin α4 (ACTN4), is a nuclear receptor coactivator that promotes proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1850–1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang C., Norris J. D., Grøn H., Paige L. A., Hamilton P. T., Kenan D. J., Fowlkes D., McDonnell D. P. (1999) Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear receptor-coactivator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries. Discovery of peptide antagonists of estrogen receptors α and β. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8226–8239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shapovalov M. V., Dunbrack R. L. (2007) Statistical and conformational analysis of the electron density of protein side chains. Proteins 66, 279–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brooks B. R., Bruccoleri R. E., Olafson B. D., States D. J., Swaminathan S., Karplus M. (1983) CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4, 187–217 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kao H. Y., Downes M., Ordentlich P., Evans R. M. (2000) Isolation of a novel histone deacetylase reveals that class I and class II deacetylases promote SMRT-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 14, 55–66 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Olave I. A., Reck-Peterson S. L., Crabtree G. R. (2002) Nuclear actin and actin-related proteins in chromatin remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 755–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeong K. W., Lee Y. H., Stallcup M. R. (2009) Recruitment of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex to steroid hormone-regulated promoters by nuclear receptor coactivator flightless-I. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29298–29309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shen X., Ranallo R., Choi E., Wu C. (2003) Involvement of actin-related proteins in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Mol. Cell 12, 147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rando O. J., Zhao K., Janmey P., Crabtree G. R. (2002) Phosphatidylinositol-dependent actin filament binding by the SWI/SNF-like BAF chromatin remodeling complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 2824–2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bannister A. J., Miska E. A. (2000) Regulation of gene expression by transcription factor acetylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 1184–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sterner D. E., Berger S. L. (2000) Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 435–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yang X. J. (2004) Lysine acetylation and the bromodomain. A new partnership for signaling. BioEssays 26, 1076–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glozak M. A., Sengupta N., Zhang X., Seto E. (2005) Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene, 363, 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soutoglou E., Katrakili N., Talianidis I. (2000) Acetylation regulates transcription factor activity at multiple levels. Mol. Cell 5, 745–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thomas M., Dadgar N., Aphale A., Harrell J. M., Kunkel R., Pratt W. B., Lieberman A. P. (2004) Androgen receptor acetylation site mutations cause trafficking defects, misfolding, and aggregation similar to expanded glutamine tracts. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8389–8395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.