Background: UDP-GlcNAc is a precursor of glycoconjugates, including hyaluronan, and induces protein glycosylation to form O-linked GlcNAc (O-GlcNAcylation).

Results: UDP-GlcNAc induces hyaluronan synthesis through O-GlcNAcylation of hyaluronan synthase 2, which stabilizes the enzyme and prevents its proteasomal degradation.

Conclusion: O-GlcNAcylation of hyaluronan synthase 2 can control synthesis of extracellular matrices with hyaluronan.

Significance: UDP-GlcNAc could control cell microenvironments that are altered in many pathologies, including vascular diseases and cancer.

Keywords: Extracellular Matrix, Glycobiology, Hyaluronate; O-GlcNAcylation, Protein Stability, Covalent Enzyme Regulation

Abstract

Hyaluronan (HA) is a glycosaminoglycan present in most tissue microenvironments that can modulate many cell behaviors, including proliferation, migration, and adhesive proprieties. In contrast with other glycosaminoglycans, which are synthesized in the Golgi, HA is synthesized at the plasma membrane by one or more of the three HA synthases (HAS1–3), which use cytoplasmic UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine as substrates. Previous studies revealed the importance of UDP-sugars for regulating HA synthesis. Therefore, we analyzed the effect of UDP-GlcNAc availability and protein glycosylation with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAcylation) on HA and chondroitin sulfate synthesis in primary human aortic smooth muscle cells. Glucosamine treatment, which increases UDP-GlcNAc availability and protein O-GlcNAcylation, increased synthesis of both HA and chondroitin sulfate. However, increasing O-GlcNAcylation by stimulation with O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino-N-phenylcarbamate without a concomitant increase of UDP-GlcNAc increased only HA synthesis. We found that HAS2, the main synthase in aortic smooth muscle cells, can be O-GlcNAcylated on serine 221, which strongly increased its activity and its stability (t½ >5 h versus ∼17 min without O-GlcNAcylation). S221A mutation prevented HAS2 O-GlcNAcylation, which maintained the rapid turnover rate even in the presence of GlcN and increased UDP-GlcNAc. These findings could explain the elevated matrix HA observed in diabetic vessels that, in turn, could mediate cell dedifferentiation processes critical in vascular pathologies.

Introduction

Cardiovascular pathologies are the most common causes of death in Western countries and are often determined by vessel wall thickening due to endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cell (SMC)5 dedifferentiation, proliferation and migration, lipid accumulation, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Although the etiology is not completely understood, the extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling has a critical role for the onset of vascular diseases (1). The glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan (HA), other proteoglycans, including versican, and matrix metalloproteinases accumulate within the neointima and strongly induce SMC growth, motility, LDL binding, and monocyte recruitment, which promotes vessel thickening (2–5). The crucial role of HA has been demonstrated in transgenic animals overexpressing HAS2 as well as in mice lacking the HA receptor CD44, which are prone to and protected from atherosclerosis, respectively (6, 7).

HA is one of the main and ubiquitous constituents of mammalian cellular microenvironments and ECMs. It is formed by the repetition of the disaccharide glucuronic acid (GlcUA) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to form large polysaccharides up to 10 MDa (8). Although HA has a simple structure without sulfation, branching, epimerization, or a core protein, it has a plethora of effects that include the control of cell growth, migration, and survival, as well as the regulation of developmental and inflammatory processes, and therefore, it is involved in several pathologies. How these functions are orchestrated by HA remains partially unsolved although its molecular mass, its turnover, and its receptors are critical for HA biological activities (9).

As HA promotes atherogenesis, it is important to understand how cells regulate its metabolism. HA is synthesized by three different isoenzymes (HAS1–3) located in the plasma membrane, whereas HA degradation is mediated by a series of hyaluronidases that produce HA fragments that can modulate inflammation and immune responses (8, 10). HASes polymerize activated sugars (i.e. UDP-GlcUA and UDP-GlcNAc) onto the reducing end of the HA chain and directly extrude the growing GAG chain into the ECM. Therefore, regulation of HASes, together with HA degradation, are main control points to determine tissue HA content. HASes can be regulated by different mechanisms, including growth factor- and hormone-mediated gene expression, availability of UDP-sugar substrates (11, 12), and ubiquitination (13, 14). Recently, we found that HAS2, but not HAS1 or HAS3, is strictly regulated by the ATP/AMP ratio through AMP-activated protein kinase, the principal energy sensor of the cell (15). Moreover, as HASes are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and pass through the Golgi to the plasma membrane, their cytosolic domains are exposed to changes in UDP-sugars that can be driven by stresses such as hyperglycemia. For example, mesangial cells dividing in hyperglycemic medium activate HAS2 in intracellular compartments, which initiates ER stress, autophagy, and formation of a monocyte-adhesive HA matrix (16).

Hyperglycemia induces vascular damages that are the main complications of diabetic patients. The increased glucose availability induces nonenzymatic glycosylation of proteins and lipids, oxidative stress, and protein kinase C activation (17, 18), and through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP), it greatly increases UDP-GlcNAc, which in turn greatly increases the nucleo-cytoplasmic protein glycosylation with O-linked GlcNAc (O-GlcNAcylation) (19, 20). O-GlcNAcylation is a reversible post-translational modification of serines/threonines that often alternates with protein phosphorylation and is controlled by two enzymes, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAc hydrolase (OGA), that can work as nutrient sensors (21). O-GlcNAcylation regulates many cellular functions, including signaling, gene expression, degradation, and trafficking (22).

HA accumulates in arteries in diabetic patients and in a porcine model for diabetes and is linked to diabetes-related vasculopathies (23, 24). In this study, we investigated the role of increased UDP-GlcNAc in primary human AoSMCs and the role of induced O-GlcNAcylation of HAS2, the key enzyme in HA synthesis in these cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Cultures and Treatments

Primary human AoSMCs were purchased from Lonza and were grown for 4–8 passages in complete SmGm2 culture medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% FBS as described previously (25). 3 × 105 cells were seeded in 35-mm dishes, and after 6 h, SmGm2 medium was replaced with DMEM (Euroclone) supplemented with 0.2% FBS. After 48 h to induce quiescence, the medium was changed to low glucose (5 mm) DMEM/F-12 with 10% FBS, and the cells were treated without or with 2 mm GlcN, 40 μm 6-diazo-5-oxo-leucine (DON), 5 mm alloxan, 100 μm O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino-N-phenylcarbamate (PUGNAC), or 1 mm 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) for 24 h (all from Sigma) to modulate protein O-GlcNAcylation (26). In some experiments, NIH3T3 cells were used and grown to confluence in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Glutamax (Lonza). After preliminary experiments, a final concentration of 4 mm GlcN, 150 μm PUGNAC, or 40 μm DON was used for 24 h.

For stable transfections, human HAS2 with an N-terminal c-Myc tag in pcDNA3 (c-Myc-HAS2) was transfected in NIH3T3 cells using Exgen 500 (Fermentas), and clones were selected in 400 μg/ml G-418 (Euroclone). Expression levels were assayed by Western blots with anti-c-Myc monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to generate the HAS2 S221A mutation following the manufacturer's instruction.

GAG Determinations

HA and chondroitin sulfate (CS) released into the culture medium were purified by proteinase K (Finnzymes) and ethanol precipitation. Streptococcus dysgalactiae hyaluronidase and chondroitinase ABC (Seikagaku) were used to obtain the unsaturated Δdisaccharides that were fluoro-tagged with 2-aminoacridone and quantified by HPLC analyses or PAGE of fluorophore-labeled saccharides (PAGEFS) (27, 28).

Western Blots

Western blot experiments were done with the monoclonal antibody CTD110.6 (Sigma) that detects O-GlcNAcylated proteins, with polyclonal antibody against GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or with a monoclonal anti-tubulin antibody (Sigma) as a control. In some experiments the anti-c-Myc antibody was also used to detect recombinant c-Myc-HAS2 fusion protein.

Cell Mobility, Adhesion, and Particle Exclusion Assays

Confluent quiescent AoSMCs were scratched by the pipette tip and then cultured in different conditions. Migrated cells were quantified after 6 h as described previously (29). Monocyte adhesive properties of AoSMCs in different conditions were tested with U937 monocyte adhesion assays. This experiment was done essentially as described previously (29) with the exception that the binding phase of monocytes with AoSMCs was done at 37 °C for 1 h. To quantify the pericellular HA coat, particle exclusion assays using paraformaldehyde-fixed human red blood cells were done on untreated and treated AoSMCs as described previously (15).

Immobilization of O-GlcNAc-modified Proteins with Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA)

NIH3T3 cells were transfected by using cationic linear polyethyleneimine Exgen 500 (Fermentas), which ensured high transfection efficiency with low toxicity when used with cell lines. Primary AoSMCs were nucleofected by using Amaxa Nucleofector (Lonza) to have a transfection efficiency of about 60% as described previously (5). Plasmids coding for 6myc-HAS2, OGT, or empty vector (pcDNA3) were used in both transfection and nucleofection experiments. The next day, cells were treated to modulate protein O-GlcNAcylation, and after 24 h of incubation, growth medium was removed, and the cells were scraped in Lysis Buffer (10 mm Tris, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)). The crude membrane preparations were incubated in ice for 5 min and sonicated, and protein contents were quantified by using the Bradford assay (Sigma). 100 μg of total proteins were incubated with 100 μl of WGA-conjugated agarose beads (Vector Laboratories) or, as binding control, with unconjugated agarose beads. The preparations were rotated for 20 h at 4 °C. The WGA-conjugated beads were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with lysis buffer containing 20 mm GlcNAc to remove nonspecific binding as described previously (30). Immobilized glycoproteins were then eluted by incubating with 1 m GlcN. Eluted proteins were denatured by boiling before polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and Western blot analyses were done to identify eluted proteins.

HAS Activity Assay

The quantification of HAS enzymatic activity was done with microsomes prepared from NIH3T3 cells, as described previously (31), and was also done with proteins eluted from WGA-agarose beads. In some experiments, microsomes were pretreated with active jack bean N-acetylglucosaminidase (GlcNAcase) (Sigma) or with heat-inactivated GlcNAcase prior to determining HAS activity.

c-Myc-HAS2 Stability

Stably transfected clones with high expression of c-Myc-HAS2 were selected by growing transfected NIH3T3 cells in the presence of 400 μg/ml of G418 (Euroclone) as described elsewhere (32). They were then plated 24 h prior to treatment with 150 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), GlcN, PUGNAC, or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 at 5 μm. At different time points, Western blot analyses were done as described above to detect the time decay of c-Myc-HAS2. Band intensities were determined by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software following normalization with tubulin levels, and first order decay was assumed to calculate protein half-lives (33).

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Stable NIH3T3 cell lines overexpressing wild type or S221A c-Myc-HAS2 were grown in the presence or absence of 150 μm PUGNAC, and cells were lysed by using a Mem-PER kit (Pierce). The lysates were dialyzed with M-PER buffer (Pierce) as described previously to immunoprecipitate the Wnt receptor Frizzled-7, a multipass transmembrane protein as are HASes (34). IP was done by using an anti-c-Myc IP kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The precipitate samples were analyzed by Western blot by using CDT110.6, anti-c-Myc, and anti-HAS2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis of the data were done using analysis of variance, followed by post hoc tests (Bonferroni) using Origin 7.5 software (OriginLab). Probability values of p < 0.01 or 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Experiments were repeated three times, each time in duplicate, and data are expressed as means ± S.E.

RESULTS

UDP-GlcNAc and O-GlcNAcylation Induce Accumulation of GAGs

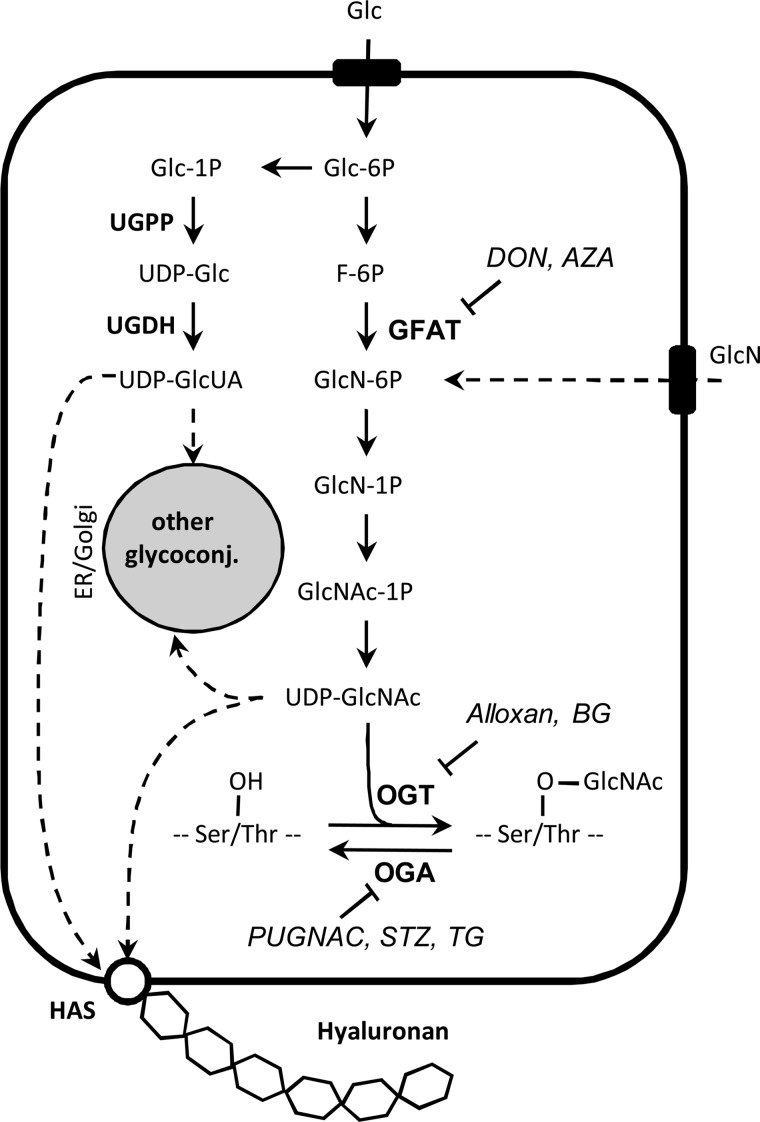

The cytosolic concentration of UDP-GlcNAc is strictly regulated, and the complex pathway (i.e. HBP) and its key points are shown in Fig. 1. In addition to synthesis of glycoconjugates, UDP-GlcNAc is a substrate for the intracellular OGT, which produces O-GlcNAcylated proteins, and this covalent post-translational modification controls several aspects of cell biology.

FIGURE 1.

HBP, biosynthesis of HA and other glycoconjugates, and protein O-GlcNAcylation. Glucose and glutamine enter the cell through the GLUT transporters. The HBP brings them to the formation of UDP-GlcNAc, and the main controlling enzyme is GFAT. UDP-GlcUA is formed starting from glucose 1-phosphate by the action of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGPP) and dehydrogenase (UGDH). UDP-GlcUA and UDP-GlcNAc can be directly used for the synthesis of HA by HAS enzymes located in the plasma membrane or can be transported inside the ER/Golgi for the synthesis of other glycoconjugates, especially proteoglycans. GlcNAc can be transferred from UDP-GlcNAc to hydroxyl groups of serine and threonine leading to O-linked GlcNAc (O-GlcNAcylation) that is regulated by the action of two enzymes, OGT and OGA. Inhibitors of GFAT, OGT, OGA, and HAS are indicated. Glc, glucose; F, fructose; GlcN, glucosamine; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; UDP, uridine diphosphate; AZA, azaserine; STZ, streptozotocin; GlcUA, glucuronic acid; TG, Thiamet G; BG, benzyl-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranoside.

To investigate a possible control of GAG synthesis by O-GlcNAcylation, we cultured AoSMCs in complete high glucose (25 mm) medium (i.e. SmGm2 with 5% FBS) up to 80% of confluence in 6-well plates. Quiescence was then induced by incubating the cells in DMEM and lowering the FBS concentration to 0.2%. After 48 h of incubation, AoSMCs were incubated in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS in 17.5 mm of glucose and treated with 2 mm GlcN, which is known to induce protein O-GlcNAcylation in the same cells (26).

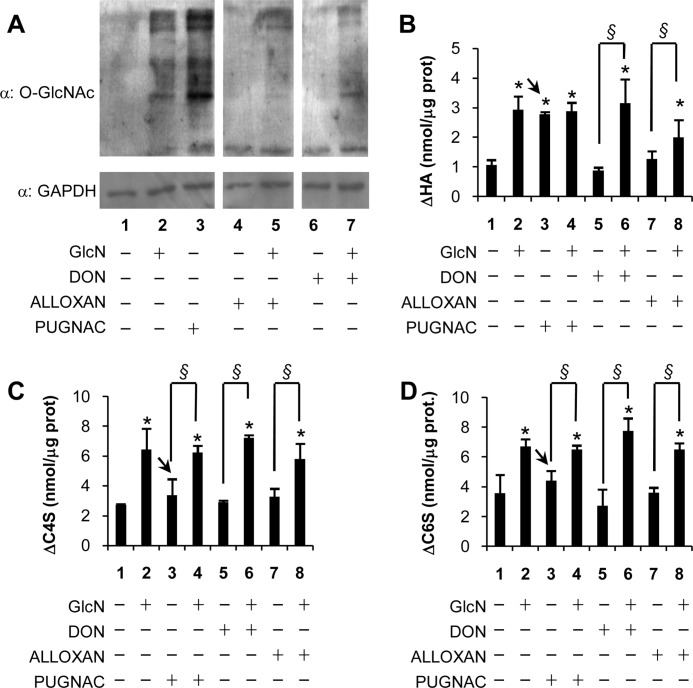

As shown in Fig. 2A (lane 2), several O-GlcNAcylated proteins were detected by Western blotting after GlcN treatment by using the specific monoclonal antibody CTD110.6 that recognizes O-GlcNAcylated proteins. We were able to reduce O-GlcNAcylation by treating AoSMCs with GlcN in the presence of alloxan, which inhibits OGT (Fig. 2A, lane 5, for a schematic view of GAG synthesis reactions and inhibitors used, see Fig. 1). In contrast, O-GlcNAcylation was not reduced when GlcN was added with DON to the level for treatment with DON alone (Fig. 2A, lane 7, compared with lane 6), which acts upstream from the GlcN entry point by inhibiting glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT). Treatments with alloxan or DON in the absence of GlcN were similar to the untreated culture control with near absence of O-GlcNAcylated proteins (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 6 compared with lane 1). Moreover, we were also able to increase O-GlcNAcylation by treating AoSMCs with PUGNAC, which inhibits OGA (Fig. 2A, lane 3) and would increase O-GlcNAcylation.

FIGURE 2.

UDP-GlcNAc availability controls GAG synthesis, whereas O-GlcNAcylation increases specifically HA synthesis. A, Western blotting analysis of 30 μg of protein extracts prepared from untreated AoSMCs grown in DMEM/F-12 or from cells treated with 2 mm GlcN, 100 μm PUGNAC, 1 mm alloxan, or 40 μm DON or in combination by using CTD 110.6 (an O-GlcNAc-specific monoclonal antibody) or anti-GAPDH antibody. B, quantification of ΔHA by HPLC prepared from GAGs released into the culture medium of AoSMCs treated as described in A. C and D, quantification of Δchondroitin 4-sulfate (ΔC4S) (C) and Δchondroitin 6-sulfate (ΔC6S) (D) by HPLC for samples prepared from GAGs released into the culture medium of AoSMCs treated as described in A. Arrows indicate the PUGNAC treatments (lanes 3) that are different in B compared with C and D. Results are expressed as means ± S.E. in three different determinations. *, p < 0.01 untreated versus treatment, respectively; §, p < 0.01.

The HPLC analyses of 2-amidoacridone fluoro-tagged specific lyase digests of GAGs extracted from the conditioned cell medium were quantified to measure the unsaturated disaccharides (Δ) derived from HA, chondroitin 4-sulfate and chondroitin 6-sulfate. Treatments with DON and alloxan added separately from GlcN did not statistically modify GAG accumulation (Fig. 2, B–D, lanes 5 and 7), but the same inhibitors with GlcN increased CS significantly and up to levels similar to GlcN alone (Fig. 2, C and D, lanes 6 and 8 compared with lane 2). Although HA also increased significantly in the GlcN cultures treated with DON and alloxan, the increase for the GlcN plus alloxan was not as high as the GlcN alone culture (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 8 compared with lane 2). Treatment with PUGNAC gave distinctly different results for HA compared with CS. PUGNAC alone increased HA synthesis to the same level as treatment with GlcN with or without PUGNAC (Fig. 2B, lanes 2–4). In contrast, CS synthesis in PUGNAC alone cultures was not statistically different from untreated cultures (Fig. 2, C and D, lanes 3 compared with lanes 1), although CS synthesis in the PUGNAC plus GlcN increased to the level of GlcN alone (Fig. 2, C and D, lanes 4 compared with lanes 2). Because PUGNAC inhibits OGA, which inhibits the hydrolysis of O-GlcNAc on proteins, these latter results suggest that O-GlcNAcylation may regulate HA synthesis without changing synthesis of CS.

HA Accumulation Induces AoSMC Migration and Monocyte Adhesion

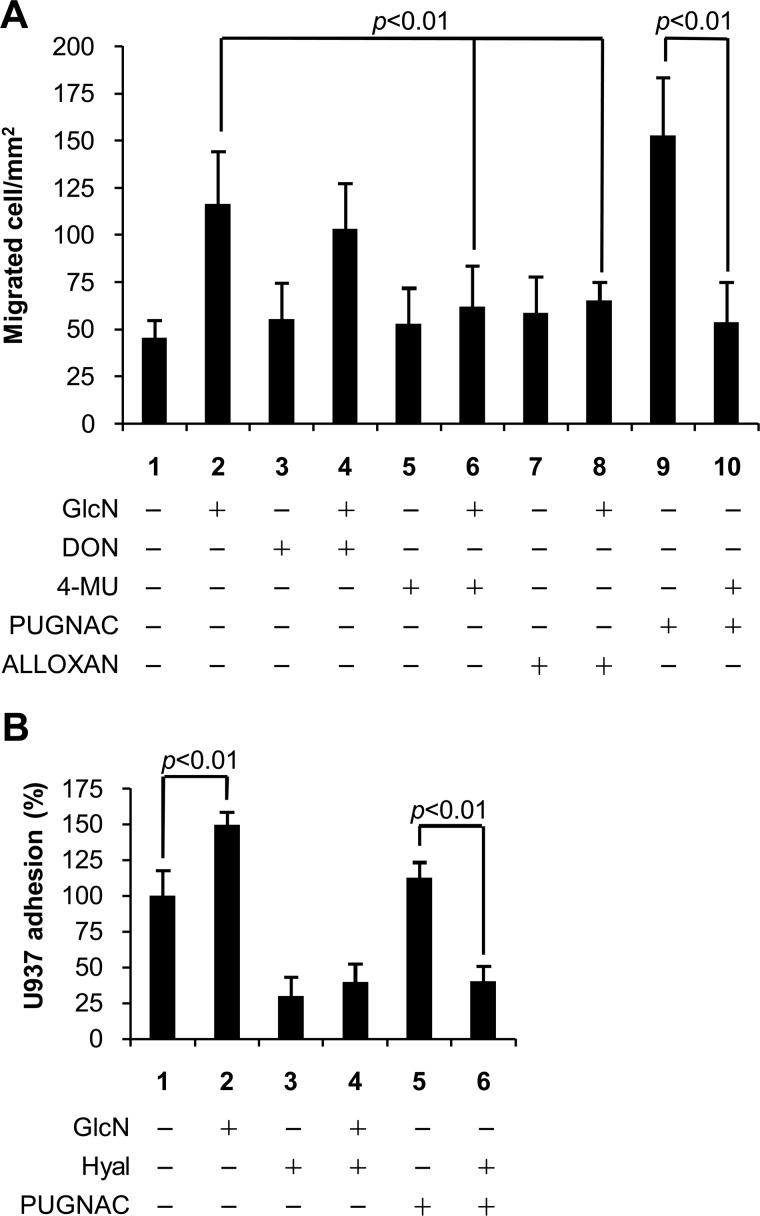

SMCs are involved in vascular diseases through their proliferation, intima invasion, and recruitment of immune cells, and HA has a role in this context (25). Therefore, we investigated whether the HA increase due to O-GlcNAcylation could regulate cell migration and adhesiveness. Fig. 3A shows the results of cell migration in scratch tests. The number of migrated AoSMCs significantly increased after treatments with GlcN, DON plus GlcN, and PUGNAC (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 4, and 9 compared with lane 1).

FIGURE 3.

O-GlcNAcylation regulates motility and adhesive proprieties of AoSMCs through HA. A, quantification of AoSMC mobility. Quiescent and confluent AoSMCs were left untreated or treated with 2 mm GlcN, 40 μm DON, 1 mm 4-MU, 100 μm PUGNAC, 5 mm alloxan, or different combinations and were scratched by using a pipette tip. After 6 h, migrated cells were counted. B, relative quantification of U937 monocyte adhesion assays. Fluorescent U937 monocytes were added to quiescent AoSMCs left untreated or treated with 2 mm GlcN, 100 μm PUGNAC, 2 units/μl hyaluronidase SD (Hyal), or different combinations. After 30 min of incubation at 4 °C, AoSMCs were washed and monocytes counted. In control experiments, AoSMCs were pretreated with hyaluronidase for 1 h at 37 °C. Results are expressed as the relative number of adherent U937 cells per field and represent the mean ± S.E.

Cell migration in AoSMC cultures treated with DON or alloxan alone was the same as migration in control cultures (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 7 compared with lane 1). Cell migration increased significantly in cultures treated with GlcN (Fig. 3A, lane 2 compared with lane 1), and the presence of DON with GlcN also increased migration (lane 4 compared with lane 3). In contrast, cell migration in cultures treated with alloxan in the presence of GlcN was not increased (Fig. 3A, lane 8 compared with lane 7). These results indicate that GlcN treatment can bypass the HBP (GFAT) block by DON but cannot bypass the O-GlcNAcylation step (OGT) blocked by alloxan (Fig. 1).

The results with PUGNAC, which inhibits hydrolysis of O-GlcNAc (Fig. 1), provide further support for this mechanism. Cultures treated with PUGNAC in the absence of GlcN increased HA synthesis (Fig. 2B, lane 3) and also increased cell migration significantly (Fig. 3A, lane 9 compared with lane 1). Treatment of cultures with PUGNAC and 4-MU, which inhibits HA synthesis but not CS synthesis (supplemental Fig. S1), blocked the increase in cell migration (Fig. 3A, lane 10 compared with lane 9). Treatment of cultures with 4-MU alone or in the presence of GlcN did not increase cell migration (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 6). These results provide evidence for a direct role of increased HA synthesis in increasing cell migration and suggest that O-GlcNAcylation of HAS may be involved.

To test whether the HA increase due to O-GlcNAcylation could regulate inflammatory cell adhesion, we measured the number of fluorescent U937 monocytes that adhered on AoSMC monolayer cultures. As shown in Fig. 3B, cultures treated with GlcN increased monocyte adhesion compared with control cultures (lane 2 compared with lane 1), and pretreatment with hyaluronidase substantially reduced monocyte adhesion for both control and GlcN-treated cultures (lanes 3 and 4 compared with lanes 1 and 2). Pretreatment with hyaluronidase also decreased monocyte adhesion to PUGNAC-treated cultures to the same level (Fig. 3B, lane 5 compared with lane 6). The results with PUGNAC suggest that the increased HA due to O-GlcNAcylation induced synthesis of a monocyte adhesive HA matrix. The presence of HA pericellular matrices in GlcN- and PUGNAC-treated AoSMCs was demonstrated by a particle exclusion assay using fixed red blood cells (supplemental Fig. S2). The pretreatment with hyaluronidase also showed that the monocyte adhesion was actually due to HA and not to the other GAGs induced by GlcN treatment.

O-GlcNAcylation of Ser-221 on HAS2 Mediates an Alteration of Protein Stability

In the experiments showed in Fig. 2, we described that PUGNAC treatment induces a specific HA accumulation without altering CS synthesis. Therefore, we tested whether the molecular mechanism could be due to O-GlcNAcylation of HASes, which utilizes cytosolic substrates and are exposed to OGT and inhibition of OGA by PUGNAC (Fig. 1). In contrast, the other GAG synthases are in the Golgi and should not be exposed to O-GlcNAcylation and hence would not be directly exposed to the effects of PUGNAC.

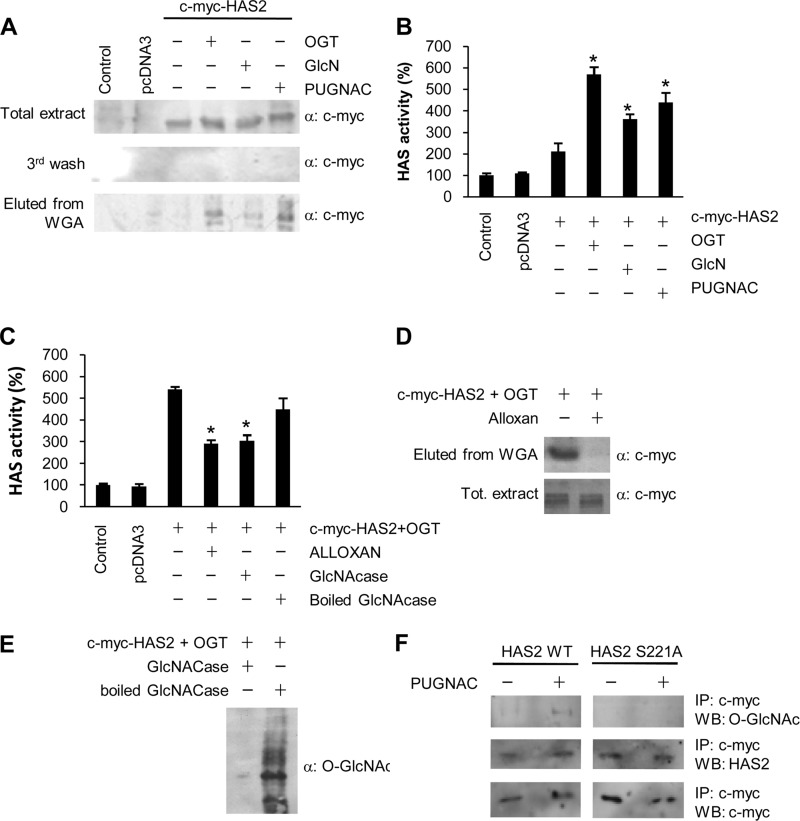

We studied whether HAS2, the main HA synthetic enzyme in AoSMCs (15), could be modified by O-GlcNAcylation. NIH3T3 cells were used for convenience, and after preliminary experiments, we were able to modulate protein O-GlcNAcylation with the same treatments as shown in Fig. 2A for AoSMC cultures (supplemental Fig. S3). NIH3T3 cells were transfected with plasmids coding for c-Myc-HAS2 alone, with a plasmid for OGT, or with an empty vector (pcDNA3). Transfected cells were left untreated or treated with GlcN or PUGNAC. After 24 h of incubation, O-GlcNAcylated proteins were purified from crude membrane preparations by binding to WGA agarose-beads. Fig. 4A shows that c-Myc-HAS2 was clearly detected in all total protein extracts from the transfected cells. However, after WGA purification, the c-Myc-HAS2 band was visible and greatly increased in cultures cotransfected with a plasmid coding for OGT, which increases O-GlcNAcylation, and in cultures treated with PUGNAC, which also increases O-GlcNAcylation by inhibiting O-GlcNAc hydrolysis. The results indicate that HAS2 is an O-GlcNAcylated enzyme. As the final third wash of WGA beads was completely negative for c-Myc-HAS2, we can exclude an effect due to bead overload. Moreover, control experiments using unconjugated agarose beads (supplemental Fig. 4) demonstrated that c-Myc-HAS2 specifically bound to WGA indicating its glycosylation.

FIGURE 4.

HAS2 O-GlcNAcylation of serine 221 increases HAS activity. A, Western blotting analysis of 30 μg of proteins prepared from NIH3T3 cells that were left untreated, transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3), with c-Myc-HAS2, or with OGT coding plasmids. After 24 h, transfected cells were treated with 4 mm GlcN or 150 μm PUGNAC and incubated for another 24 h. Crude membrane preparations were obtained as described under “Experimental Procedures” and were incubated with WGA-conjugated agarose beads. After three washes (the last is shown), WGA-associated proteins were eluted. Western blots were done by using anti-c-Myc antibody. B, relative quantification of HAS enzymatic activity in microsomes prepared from NIH3T3 cells transfected and treated as in A. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. in three different determinations. *, p < 0.01 control versus treatments, respectively. C, relative quantification of HAS enzymatic activity in microsomes prepared from NIH3T3 cells that were left untreated, transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3), cotransfected with c-Myc-HAS2 + OGT coding plasmids, or cotransfected with c-Myc-HAS2 + OGT and treated with 5 mm alloxan, followed by incubation for 24 h. To verify that the increment of HAS activity was due to O-GlcNAc, microsomes from cells cotransfected with c-Myc-HAS2 + OGT were pretreated with 1 unit of GlcNAcase or, as control, heat-inactivated GlcNAcase. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. in three different determinations. *, p < 0.01 c-Myc-HAS2 + OGT versus treatments, respectively. D and E, efficiency of alloxan and GlcNAcase treatments to inhibit or hydrolyze O-GlcNAc from proteins, respectively. D, Western blot analysis of 30 μg of proteins prepared from NIH3T3 cells cotransfected with plasmids coding for c-Myc-HAS2 + OGT and left untreated or treated with 5 mm alloxan to inhibit OGT. After 24 h, O-GlcNAcylated proteins were prepared by using WGA-conjugated agarose beads. After three washes, WGA associated proteins were eluted with GlcN. Western blots were done by using anti-c-Myc antibody. Analysis of the total protein extract before WGA incubation was used as a control. E, Western blot analysis of 30 μg of proteins prepared from NIH3T3 cells cotransfected with plasmids coding for c-Myc-HAS2 + OGT. After 24 h, protein extracts were prepared from the transfected cells and incubated with 1 unit of GlcNAcase. As a control, protein extracts were incubated with heat-inactivated (boiled) GlcNAcase. Western blot was done by using CTD110.6 antibody that recognizes O-GlcNAc modified proteins. F, Western blotting (WB) analysis for O-GlcNAc of immunoprecipitated wild-type (WT) or mutated c-Myc-HAS2 (S221A) from stable NIH3T3 cell lines untreated or treated with 4 mm of GlcN for 24 h.

Because O-GlcNAcylation controls several aspects of protein metabolism, we studied whether the HAS2 O-GlcNAcylation could regulate its enzymatic activity. NIH3T3 cells were transfected and treated as described above. Microsomes containing plasma membranes were purified by centrifugation, and the HAS enzymatic activity was quantified as reported previously (15). Fig. 4B shows that the transfection of c-Myc-HAS2 alone only slightly increased HA synthetic activity, whereas cotransfection with a plasmid coding for OGT or the treatment with GlcN or PUGNAC increased HAS activity. Because OGT and PUGNAC treatments increased c-Myc-HAS2 O-GlcNAcylation, we propose that the O-GlcNAcylation increased HAS2 synthetic capability. To test this, we treated the cotransfected c-Myc-HAS2 and OGT cells with alloxan to prevent O-GlcNAcylation. This significantly decreased HAS activity in isolated microsomes (Fig. 4C). Similarly, when O-GlcNAc was reduced by enzymatic treatment (GlcNAcase), HAS activity in the microsomes was decreased to the same extent (Fig. 4C). Both alloxan and GlcNAcase effectively inhibited and hydrolyzed O-GlcNAc, respectively (Fig. 4, D and E). Interestingly, the activity of HAS3, the only other HAS expressed in AoSMCs (15), was not significantly affected by treatments that increase O-GlcNAcylation (supplemental Fig. S5).

As O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation can compete for the same residues, we tested whether the HAS2 threonine 110, which we previously demonstrated to be phosphorylated by AMP-activated protein kinase (15), could also be glycosylated by O-GlcNAc. NIH3T3 cells were transiently transfected with the vector coding for T110A HAS2, or cotransfected with OGT, or treated with alloxan. After 48 h of incubation, HAS activity was measured in isolated microsomes as described above. As shown in supplemental Fig. S6, the mutation did not prevent the HA activity increase mediated by cotransfected OGT, whereas the OGT plus alloxan or plus GlcNAcase treatments prevented the increase similar to results with wild-type HAS2. This provides strong evidence that threonine 110 is not involved in the O-GlcNAcylation of HAS2 that regulates its activity.

To identify which HAS2 residue(s) could be modified by O-GlcNAc, we used the YinOYang server. Although a consensus sequence has never been identified for O-GlcNAcylation, recent crystallography data revealed that OGT prefers sequences in which the residues flanking the glycosylated amino acid enforce an extended conformation (for example, prolines and β-branched amino acids) (35). Using these approaches, excluding residues in common with HAS3 (whose activity is not stimulated by O-GlcNAc increase), as well as amino acids in transmembrane segments or in extra-cytoplasmic loops, we identified serine 221 (Ser-221) as a putative OGT target. Therefore, by site-directed mutagenesis, we generated a c-Myc-HAS2 construct in which Ser-221 was mutated to alanine (S221A). This latter vector and that coding for wild-type c-Myc-HAS2 were used to generate stable NIH3T3 cell lines expressing c-Myc-HAS2 S221A and c-Myc-HAS2. The use of stable expressing cell lines prevents artifacts due to different transfection efficiency and/or induction of stress response due to protein overexpression that is often observed in transient transfection experiments. These two cell lines were left untreated or treated with PUGNAC to induce protein O-GlcNAcylation. Wild-type and mutated c-Myc-HAS2 proteins were purified by IP by using the c-Myc tag. As shown in Fig. 4F, the anti O-GlcNAc antibody CTD110.6 detected a band only in the wild-type c-Myc-HAS2 treated with PUGNAC, confirming the data obtained with WGA and indicating that S221A is the main residue to be modified by O-GlcNAc.

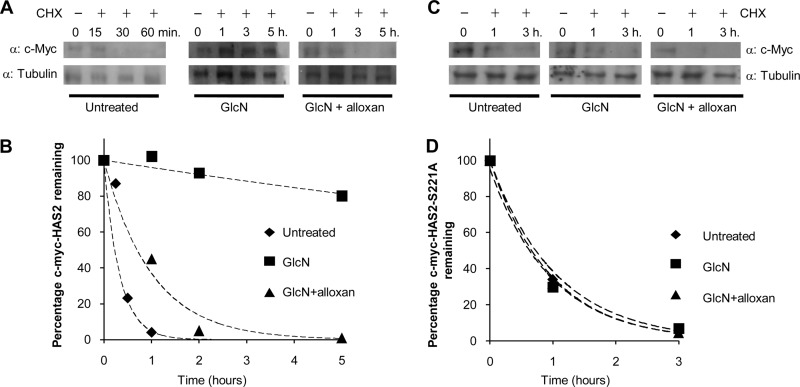

To understand the molecular mechanism that increases activity of O-GlcNAcylated HAS2 compared with unmodified HAS2, we investigated their stability. The stable expressing NIH3T3 cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to block new protein synthesis, and Western blots were used to detect c-Myc-HAS2 after different incubation times. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, c-Myc-HAS2 turned over rapidly and completely disappeared after 30 min after blocking protein synthesis. Based on these data and assuming a first order decay (33), it was possible to calculate a c-Myc-HAS2 half-life (t½) of about 17 min. This short time can explain the low abundance of HAS2 protein in the cells, although the protein tag (i.e. c-Myc) could influence the half-life (33). Interestingly, time course experiments of GlcN-treated cells after blocking protein synthesis with CHX greatly increased the t½ value of the O-GlcNAcylated form of c-Myc-HAS2 to greater than 5 h (Fig. 5, A and B). The critical role of O-GlcNAc binding was confirmed with cells that were treated with both GlcN and alloxan before blocking protein synthesis. This decreased the t½ to about 80 min, nearly 4-fold lower than treatment with GlcN alone (Fig. 5, A and B). This specific inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation by alloxan indicates such glycosylation can strongly stabilize c-Myc-HAS2. Similar experiments were done by using a stable cell line overexpressing the mutant c-Myc-HAS2-S221A (Fig. 5, C and D). The mutation of the O-GlcNAcylable Ser-221 to alanine generated an enzyme with a calculated t½ of about 70 min. Interestingly, the treatment with GlcN or GlcN + alloxan did not significantly change protein stability suggesting that the loss of O-GlcNAc maintained a rapid turnover enzyme.

FIGURE 5.

Determination of half-life of c-Myc-HAS2 and c-Myc-HAS2-S221A with or without O-GlcNAcylation. A, representative Western blot for an experiment in which an NIH3T3 cell line that stably expressed c-Myc-HAS2 was left untreated, treated with 4 mm of GlcN, or with 4 mm of GlcN + 2 mm alloxan in the presence of 150 μm/ml CHX. At the indicated times, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed in Western blots by using anti-c-Myc and as a control anti-tubulin antibody. Note that in the untreated samples, short incubation times were used because c-Myc-HAS2 was completely degraded at longer incubations. Blot images were acquired and quantified with a densitometer. B, c-Myc-HAS2 degradation kinetics. Intensity of the c-Myc-HAS2 bands in A were quantified and calculated as a percentage of the intensity of the band at time 0 for each treatment. The lines represent exponential fitting to the experimental data. C, representative Western blot for an experiment in which an NIH3T3 cell line that stably expressed the mutated c-Myc-HAS2-S221A was left untreated or treated as described in A. D, c-Myc-HAS2-S221A degradation kinetics calculated as in B.

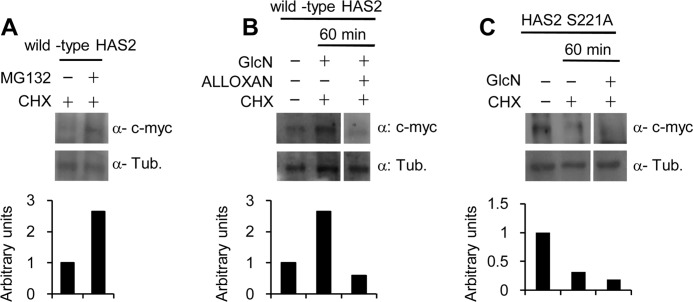

To better understand the molecular mechanism that underlies the rapid c-Myc-HAS2 turnover, we studied the involvement of the 26 S proteasome. The stable NIH3T3 cell line overexpressing wild-type c-Myc-HAS2 was treated with CHX for 60 min in the presence of the 26 S proteasome inhibitor MG132. Fig. 6A shows that MG132 effectively inhibited c-Myc-HAS2 degradation, which indicates that the rapid turnover of c-Myc-HAS2 involves the 26 S proteasome. Interestingly, the addition of GlcN with CHX inhibited c-Myc-HAS2 degradation, whereas the addition of alloxan with CHX and GlcN increased c-Myc-HAS2 degradation compared with untreated control (Fig. 6B). The mutation of the Ser-221 to alanine, which prevents HAS2 O-GlcNAcylation, produced an enzyme with a turnover comparable with the wild-type protein. After 60 min of incubation with CHX, the mutated enzyme band almost disappeared, and as expected, GlcN did not prevent this decrease in contrast to its effect on the wild-type c-Myc-HAS2 (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

HAS2 O-GlcNAcylation increases HAS stability. A, representative Western blots for an experiment in which an NIH3T3 cell line that stably expressed c-Myc-HAS2 (clone 8) was treated with 150 μm/ml CHX in the presence or absence of 5 μm MG132. After 60 min of incubation, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for c-Myc-HAS2 and tubulin. B, representative Western blots for an experiment in which clone 8 cells were left untreated or treated with combinations of GlcN, alloxan, or CHX. After 60 min of incubation, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for c-Myc-HAS2 and tubulin (Tub). C, representative Western blots for an experiment in which an NIH3T3 cell line that stably expressed the mutant c-Myc-HAS2 S221A were left untreated or treated with a combination of GlcN and CHX. After 60 min of incubation, cell extracts were prepared and used to analyze the mutated c-Myc-HAS2 and tubulin. All lower panels show the quantification of the bands relative to tubulin.

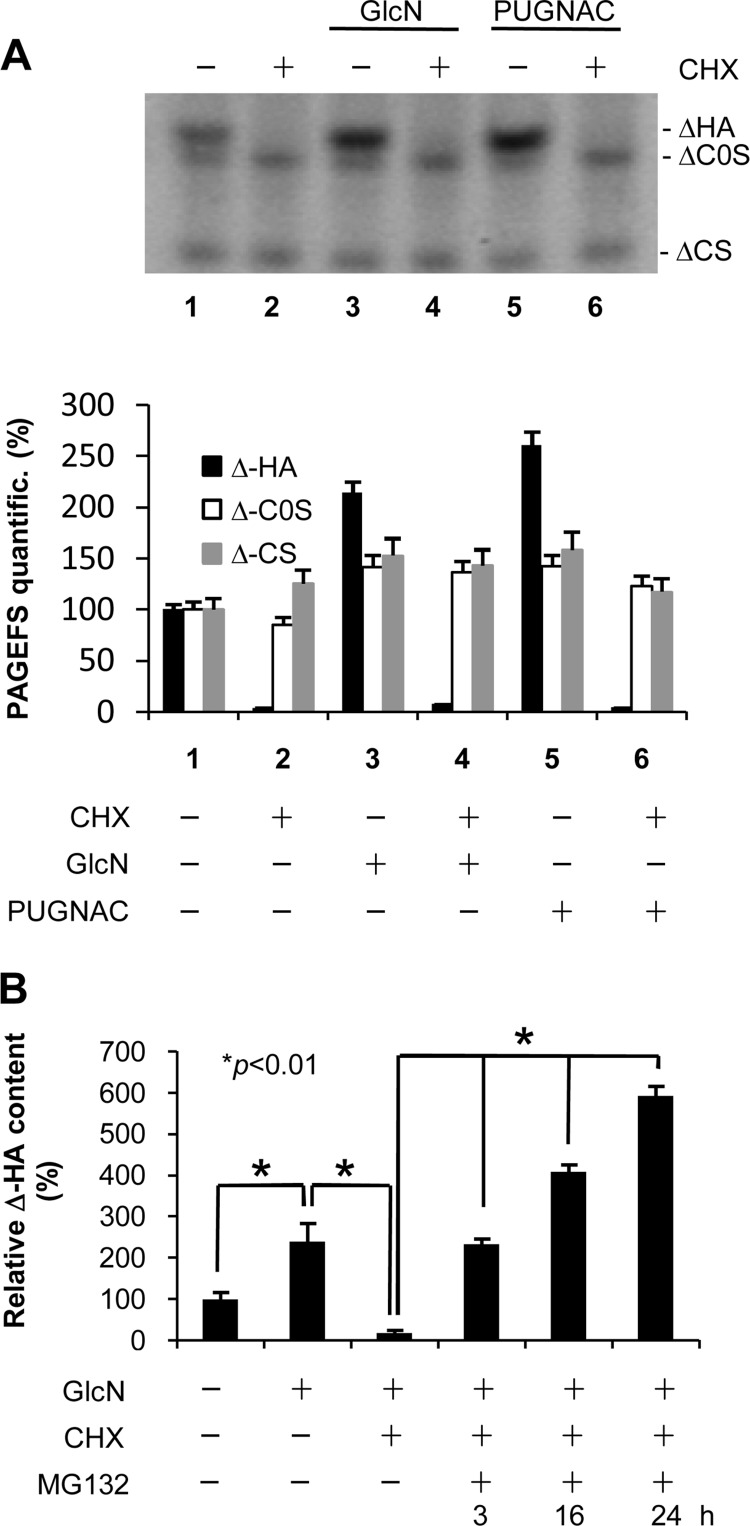

To study the effect of protein stability on cellular GAG metabolism, we treated AoSMCs with CHX for 24 h and analyzed secreted GAGs by using PAGEFS, which permits a rapid comparison of multiple GAG Δ disaccharides in a polyacrylamide gel. As shown in Fig. 7A, HA completely disappeared after CHX treatment, whereas the CS level remained substantially unaltered (lane 2 compared with lane 1) or increased (lane 2 compared with lane 3 and 5), indicating that HA is the unique GAG to have a very high turnover in vitro. Furthermore, HA degradation was still apparent when either GlcN or PUGNAC was added with CHX (Fig. 7A, lanes 4 and 6 compared with lanes 3 and 5). The treatment with GlcN and PUGNAC alone induced an increment of both HA and CS as expected (lane 1 compared with lanes 3 and 5). In contrast, treatment with MG132, the proteasome inhibitor, was able to sustain HA synthesis and accumulation into the culture medium in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Involvement of protein stability and proteasome inhibition in regulation of GAG secretion in AoSMCs. A, representative PAGEFS analyses of the culture media from untreated and 24-h treated AoSMCs with different combinations of 2 mm GlcN, 100 μm PUGNAC, and 7 μg/ml CHX. ΔHA and ΔC0S indicate HA and chondroitin 0 sulfate disaccharides, respectively, and ΔCS indicates a band composed of chondroitin 4- and 6-sulfate disaccharides that were not resolved in the gel. The lower panel represents the relative quantification of PAGEFS bands done by ImageJ software. B, relative quantification of ΔHA prepared from GAGs released into the culture media of AoSMCs left untreated or treated with different combinations of GlcN and CHX. After 24 h, MG132 (5 μm) was added to GlcN + CHX-treated cells, and aliquots of culture media were withdrawn at the indicated times for HA determination. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. in three different determinations.

DISCUSSION

HA, a ubiquitous component of cellular microenvironments, has critical effects on cell behavior in physiological as well as in pathological conditions (8). Some HA effects include morphogenesis and tissue injury repair, although in different situations, HA can exert negative effects favoring cancer progression and contributing to vascular wall thickening. Even if an increasing body of literature addresses the HA synthesis regulation (for a recent review see Ref. 14), this process has remained largely unclear. In this work, we describe for the first time that HAS2 can be modified by O-GlcNAc on serine 221, which stabilizes the enzyme by inhibiting its proteasomal degradation. In addition we demonstrated that HA accumulation in cell medium, but not that of chondroitin sulfates, is strictly regulated by protein turnover and 26 S proteasome.

O-GlcNAcylation is mediated by OGT and OGA and is strictly dependent on UDP-GlcNAc, the substrate of OGT. Interestingly, UDP-GlcNAc concentrations can greatly vary depending on substrates that enter into the HBP. Therefore, UDP-GlcNAc can be considered a nutrient sensor (21). Increased UDP-GlcNAc concentration increases protein O-GlcNAcylation, which controls a plethora of cellular enzymes and is becoming one of the most studied modifications induced by hyperglycemia (36). Because major diabetic complications are at the vascular level (19), we studied commercial AoSMCs, which are crucial for vessel thickening and are able to produce HA in specific conditions.

In our experiments, untreated AoSMCs cultured in medium with 17.5 mm glucose typical of DMEM/F-12 did not show significant levels of O-GlcNAcylated proteins suggesting that the cells used in these experiments were probably insulin-dependent for glucose uptake as debated previously. In fact, whether insulin, at physiological concentrations, has direct effects on vascular SMCs remains controversial (37, 38). In light of these considerations, the high concentration of glucose in the cell cultures did not induce hyperglycemic conditions in cell cytoplasm and consequently did not increase intracellular UDP-GlcNAc concentration. To significantly induce protein O-GlcNAcylation, we added 2 mm GlcN to the cells as described previously in AoSMCs (26). This amino-sugar enters in the cells using an insulin-independent and highly efficient GLUT2 transporter (39).

The first consideration stemming from this study is that in AoSMCs the HBP controls UDP-GlcNAc availability, the substrate critical for the synthesis of HA as well as for other GAGs and glycoproteins. Although GlcNAc is a specific component of only HA and heparin/heparin sulfate GAGs, the UDP-GlcNAc epimerase establishes an equilibrium with UDP-GalNAc, which is a critical component of CS (40). It has also been shown that UDP-GlcUA, the other substrate necessary for all GAG synthesis except keratan sulfate, increases after GlcN treatments (41). These observations suggest that there is a fine-tuning among the cytosolic sugar nucleotides in regulating GAG synthesis (41). GlcN addition to the AoSMC cultures increased synthesis of both HAs, which uses cytosolic UDP-sugar substrates, and CS, which utilizes UDP-sugar substrates that are transported into the Golgi by antiporters. The increases were inhibited by DON, which blocks GFAT and inhibits entry into the HBP thereby inhibiting increased UDP-GlcNAc (Fig. 1). Treatment with alloxan, which inhibits O-GlcNAcylation, did not prevent increased synthesis of HA and CS in the presence of GlcN, but the increase was less than with GlcN alone. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that elevated UDP-GlcNAc levels can increase general GAG levels of synthesis.

The results with PUGNAC indicate that inhibiting O-GlcNAc hydrolysis selectively affects HA synthesis. Cultures treated with PUGNAC without added GlcN increased HA synthesis significantly, but without increasing CS synthesis above control levels. Furthermore, the presence of GlcN with PUGNAC increased CS synthesis to levels for GlcN-treated cultures without increasing HA synthesis beyond cultures treated with PUGNAC in the absence of GlcN or cultures treated with GlcN alone. This provides strong evidence that protein O-GlcNAcylation can regulate HA synthetic activity.

Nucleotide-sugar transporters located on the Golgi membrane have the critical function to supply the substrates for the complex GAG synthesis system (i.e. GAGosome) (42, 43), and it was demonstrated that overexpression of the nucleotide-sugar transporter HFRC1 induced accumulation of heparan sulfate (44). Interestingly, UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, which produces UDP-glucose from glucose 1-phosphate, was reported to be O-GlcNAcylated (45). Moreover, UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase has been reported to be critical not only for glycogen but also for HA synthesis (46). This means that O-GlcNAcylation could be critical to coordinate the availability of UDP-glucose and, in turn, of UDP-GlcUA, which is crucial for GAG synthesis. Recently, it was shown that rat epidermal keratinocytes treated with GlcN accumulate HA (41), indicating that an increase of UDP-sugars and/or protein O-GlcNAcylation can be considered a general mechanism to regulate the synthesis of HA.

The molecular mechanism by which O-GlcNAcylation can induce HA accumulation could act at several levels. We proposed that HASes, having a large cytoplasmic loop critical for their activity, could be accessible to nucleo-cytoplasmic OGT. We previously demonstrated that the HAS2 intracellular domain can be recognized by AMP-activated protein kinase and that the specific phosphorylation of the threonine 110 residue inhibited the enzyme activity (15). Interestingly, the observation that CS synthetic machinery was not influenced by PUGNAC treatments provides strong evidence that the OGT may interact only with cytosolic proteins or enzymes and not with Golgi enzymes involved in sulfated GAG synthesis.

Our results clearly showed that HAS2 can be O-GlcNAcylated on the serine 221. This residue is within the large cytoplasmic loop of HAS2 that has been described to be critical for enzyme activity (47). This covalent post-translational modification strongly augments HA synthetic capability. As HAS2 is the most abundant HA synthetic enzyme in adult tissues and its specific presence is critical for development (48), it is natural that HAS2 activity needs to be finely modulated by post-translational modifications (i.e. phosphorylation, glycosylation, and/or ubiquitination) in response to different cellular situations. Moreover, HASes, having different biochemical properties (i.e. affinities toward substrates) (49), could modulate their activity depending on UDP-sugars availability.

As O-GlcNAcylated proteins are involved in transcription, translation, cytoskeletal assembly, signal transduction, stability, and many other cellular functions, we further investigated the molecular mechanism through which O-GlcNAcylation increased HAS2 activity. We previously showed that HAS2 N-glycosylation can modulate its enzymatic activity probably due to a different subcellular localization (31). However, N-glycosylation is an endoplasmic reticulum process that is unrelated with O-GlcNAcylation, HBP, and nutrient sensor. HAS2 has been recently described to be an ubiquitinated protein (13), and O-GlcNAcylation generally protects from protein degradation by modulation of proteasomal activity (21, 50). On this basis, the data on HAS2 stability presented in Figs. 5 and 6 confirmed that O-GlcNAcylation of the enzyme increased its stability. O-GlcNAcylation incremented its half-life by more than 30-fold and therefore increased the time available for its synthetic activity. Our study also provided evidence that the 26 S proteasome is involved by showing that MG132, a specific inhibitor of the proteasome, inhibited turnover of HAS2 O-GlcNAcylated at serine 221. This effect was confirmed by using a mutated S221A HAS2 and by treating the cells with the O-GlcNAcylation inhibitor alloxan. Taken together, these data clearly indicate that c-Myc-HAS2 has a very rapid turnover due to proteasomal activity, and O-GlcNAcylation of serine 221 prevents its degradation.

The mechanism of such proteasomal degradation could be complex and requires additional processes as HAS2 is a multipass transmembrane protein typically localized in the plasma membrane as well as in intracellular vesicles. These vesicles can be part of the secretory pathway to bring HAS proteins into the plasma membrane but can also derive from endocytosis or plasma membrane recycling (31). Plasma membrane proteins, including c-Met, insulin receptor, and insulin-like growth factor receptor, are known to be ubiquitinated and degraded by proteasome (51, 52), whereas other plasma membrane proteins were ubiquitinated, internalized by endocytosis, and degraded by lysosomes (53). HAS2 is known to be mono- and polyubiquitinated, and although monoubiquitination seems to be involved in enzyme dimerization, polyubiquitination does not seem directly related to proteasomal degradation (13). Recently, it was described that the short OGA isoform promotes the proteasomal degradation of surface lipid droplet proteins (54, 55) and therefore could have a role in the regulation of HAS2 degradation. Moreover, very recent literature describes the presence of an OGT in the ER (EOGT) conserved in Drosophila and mice (56, 57), which could regulate the HAS2 folding process or its escape from the ER. Proteasomal degradation is typically associated with protein misfolding events within the ER, and this could also be involved in regulation of HAS2. ER stress is known to modulate HA synthesis by altering HAS activity (31). Therefore, the process to deliver HAS2 to the proteasome could be complex and occur in different cell conditions, which will require additional efforts to be elucidated.

An intriguing issue is represented by the results of experiments in Fig. 7. In the conditions that led to HAS2 stabilization, the concomitant treatment with CHX did not correspond to an increment of HA accumulation in the cell medium. This apparent contradiction can be explained taking into account that the incubation time was 24 h and not comparable with the c-Myc-HAS2 half-life in these conditions (more than 5 h). Moreover, the HA accumulation could depend on hyaluronidase catabolic activities that could be modulated by the treatments. Interestingly, the inhibition of proteasome already after 3 h from MG132 treatment induced an accumulation of HA indicating the critical role of protein turnover in the control of ECM composition and cell microenvironment that can actively regulate cell behavior as described previously for SMC proliferation (58).

A large body of literature reports that HA is involved in cell migration, and in our experiments the O-GlcNAcylation increased HA synthesis that correlated with increased AoSMC migration. The experiments based on the use of alloxan specifically indicated that the role of O-GlcNAcylation on cell motility is crucial, whereas the increase of UDP-GlcNAc availability is less critical. It is worth noting that cell proliferation can also contribute to scratch closure in this cell migration assay. For this reason, we reduced the experiment time and studied cells after 6 h of incubation. Moreover, cell proliferation is another factor critical in vascular thickening. This issue was investigated in a study by Raman et al. (26) that clearly demonstrated protein O-GlcNAcylation strongly induced AoSMCs proliferation via thrombospondin-1. The recruitment of immune cells is a crucial step in the progression of vascular lesions contributing to inflammation. In addition to integrins and selectins, circulating monocytes can adhere to HA through interaction with CD44 (59). Therefore, an accumulation of HA in monocyte adhesive matrices can be considered a proinflammatory signal and may shed light on the role of HA in inflammatory processes. Our results highlight that O-GlcNAcylation modulates AoSMCs adhesiveness favoring monocyte tethering via HA.

From a functional point of view, it has been shown that GlcN ameliorates parameters of several diseases, including adjuvant and rheumatoid arthritis and cardiac allograft survival. In cardiovascular systems, an increase of protein O-GlcNAcylation inhibits inflammatory and neointimal responses to acute endoluminal arterial injury suggesting a vasoprotective role of this post-translational modification in vivo (60). Our results seem to show a different role of O-GlcNAcylation favoring immune cell adhesion and SMC migration. Such different effects of O-GlcNAcylation are already reported in the literature, which has highlighted simultaneous negative (i.e. increase insulin resistance, impaired Ca2+ signaling, and increased angiotensin 2 synthesis) and positive (i.e. increased cardioprotection post trauma and decreased ER and oxidative stresses) effects of O-GlcNAcylation on cardiovascular systems (61, 62).

In conclusion, our work confirmed that sugar nucleotides are critical for GAG synthesis and demonstrated that O-GlcNAcylation influences only HA production. We discovered that HAS2 has a very short half-life due to proteasome 26 S degradation and that serine 221 O-GlcNAcylation increased protein stability and HAS2 activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yang Xiaoyong (Yale University) for OGT-expressing vector and Gerald W. Hart and Stephan Hardiville (The Johns Hopkins University) for CTD110.6 antibody used in IP experiments. We acknowledge the “Centro Grandi Attrezzature per la Ricerca Biomedica,” Università degli Studi dell'Insubria, for the availability of instruments.

This work was supported in part by the Fondazione Comunitaria del Varesotto-Organizzazione Non Lucrativa di Utilità Sociale (ONLUS), the Fondo di Ateneo per la Ricerca (FAR), and a Centro Insubre di Biotecnologie per la Salute Umana young researcher award (to D. V.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- HBP

- hexosamine biosynthetic pathway; O-GlcNAcylation, protein glycosylation with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine

- GlcUA

- glucuronic acid

- HA

- hyaluronan

- AoSMC

- primary human aortic smooth muscle cell

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- GAG

- glycosaminoglycan

- HAS

- HA synthase

- GlcN

- glucosamine

- DON

- 6-diazo-5-oxoleucine

- PUGNAC

- O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino-N-phenylcarbamate

- GFAT

- glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase

- WGA

- wheat germ agglutinin

- OGT

- O-GlcNAc transferase

- OGA

- O-GlcNAc hydrolase

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- GlcNAcase

- jack bean N-acetylglucosaminidase

- 4-MU

- 4-methylumbelliferone

- CS

- chondroitin sulfate

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- PAGEFS

- PAGE of fluorophore-labeled saccharide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ross R. (1999) Atherosclerosis. An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vigetti D., Viola M., Karousou E., Genasetti A., Rizzi M., Clerici M., Bartolini B., Moretto P., De Luca G., Passi A. (2008) Vascular pathology and the role of hyaluronan. Scientific World Journal 8, 1116–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nigro J., Osman N., Dart A. M., Little P. J. (2006) Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. Endocr. Rev. 27, 242–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Riessen R., Wight T. N., Pastore C., Henley C., Isner J. M. (1996) Distribution of hyaluronan during extracellular matrix remodeling in human restenotic arteries and balloon-injured rat carotid arteries. Circulation 93, 1141–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vigetti D., Moretto P., Viola M., Genasetti A., Rizzi M., Karousou E., Pallotti F., De Luca G., Passi A. (2006) Matrix metalloproteinase 2 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases regulate human aortic smooth muscle cell migration during in vitro aging. FASEB J. 20, 1118–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chai S., Chai Q., Danielsen C. C., Hjorth P., Nyengaard J. R., Ledet T., Yamaguchi Y., Rasmussen L. M., Wogensen L. (2005) Overexpression of hyaluronan in the tunica media promotes the development of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 96, 583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cuff C. A., Kothapalli D., Azonobi I., Chun S., Zhang Y., Belkin R., Yeh C., Secreto A., Assoian R. K., Rader D. J., Puré E. (2001) The adhesion receptor CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1031–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang D., Liang J., Noble P. W. (2011) Hyaluronan as an immune regulator in human diseases. Physiol. Rev. 91, 221–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vigetti D., Rizzi M., Moretto P., Deleonibus S., Dreyfuss J. M., Karousou E., Viola M., Clerici M., Hascall V. C., Ramoni M. F., De Luca G., Passi A. (2011) Glycosaminoglycans and glucose prevent apoptosis in 4-methylumbelliferone-treated human aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 34497–34503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de la Motte C., Nigro J., Vasanji A., Rho H., Kessler S., Bandyopadhyay S., Danese S., Fiocchi C., Stern R. (2009) Platelet-derived hyaluronidase 2 cleaves hyaluronan into fragments that trigger monocyte-mediated production of proinflammatory cytokines. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 2254–2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jokela T. A., Jauhiainen M., Auriola S., Kauhanen M., Tiihonen R., Tammi M. I., Tammi R. H. (2008) Mannose inhibits hyaluronan synthesis by down-regulation of the cellular pool of UDP-N-acetylhexosamines. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7666–7673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vigetti D., Ori M., Viola M., Genasetti A., Karousou E., Rizzi M., Pallotti F., Nardi I., Hascall V. C., De Luca G., Passi A. (2006) Molecular cloning and characterization of UDP-glucose dehydrogenase from the amphibian Xenopus laevis and its involvement in hyaluronan synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8254–8263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karousou E., Kamiryo M., Skandalis S. S., Ruusala A., Asteriou T., Passi A., Yamashita H., Hellman U., Heldin C. H., Heldin P. (2010) The activity of hyaluronan synthase 2 is regulated by dimerization and ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23647–23654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tammi R. H., Passi A. G., Rilla K., Karousou E., Vigetti D., Makkonen K., Tammi M. I. (2011) Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of hyaluronan synthesis. FEBS J. 278, 1419–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vigetti D., Clerici M., Deleonibus S., Karousou E., Viola M., Moretto P., Heldin P., Hascall V. C., De Luca G., Passi A. (2011) Hyaluronan synthesis is inhibited by adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase through the regulation of HAS2 activity in human aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7917–7924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang A., de la Motte C., Lauer M., Hascall V. (2011) Hyaluronan matrices in pathobiological processes. FEBS J. 278, 1412–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aronson D., Rayfield E. J. (2002) How hyperglycemia promotes atherosclerosis. Molecular mechanisms. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 1, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sheetz M. J., King G. L. (2002) Molecular understanding of hyperglycemia's adverse effects for diabetic complications. JAMA 288, 2579–2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brownlee M. (2001) Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414, 813–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buse M. G. (2006) Hexosamines, insulin resistance, and the complications of diabetes. Current status. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290, E1–E8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Butkinaree C., Park K., Hart G. W. (2010) O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc). Extensive cross-talk with phosphorylation to regulate signaling and transcription in response to nutrients and stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1800, 96–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hart G. W., Housley M. P., Slawson C. (2007) Cycling of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature 446, 1017–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heickendorff L., Ledet T., Rasmussen L. M. (1994) Glycosaminoglycans in the human aorta in diabetes mellitus. A study of tunica media from areas with and without atherosclerotic plaque. Diabetologia 37, 286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDonald T. O., Gerrity R. G., Jen C., Chen H. J., Wark K., Wight T. N., Chait A., O'Brien K. D. (2007) Diabetes and arterial extracellular matrix changes in a porcine model of atherosclerosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 55, 1149–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vigetti D., Viola M., Karousou E., Rizzi M., Moretto P., Genasetti A., Clerici M., Hascall V. C., De Luca G., Passi A. (2008) Hyaluronan-CD44-ERK1/2 regulate human aortic smooth muscle cell motility during aging. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4448–4458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raman P., Krukovets I., Marinic T. E., Bornstein P., Stenina O. I. (2007) Glycosylation mediates up-regulation of a potent antiangiogenic and proatherogenic protein, thrombospondin-1, by glucose in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5704–5714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karousou E. G., Viola M., Genasetti A., Vigetti D., Luca G. D., Karamanos N. K., Passi A. (2005) Application of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of fluorophore-labeled saccharides for analysis of hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfate in human and animal tissues and cell cultures. Biomed. Chromatogr. 19, 761–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vigetti D., Viola M., Gornati R., Ori M., Nardi I., Passi A., De Luca G., Bernardini G. (2003) Molecular cloning, genomic organization, and developmental expression of the Xenopus laevis hyaluronan synthase 3. Matrix Biol. 22, 511–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vigetti D., Rizzi M., Viola M., Karousou E., Genasetti A., Clerici M., Bartolini B., Hascall V. C., De Luca G., Passi A. (2009) The effects of 4-methylumbelliferone on hyaluronan synthesis, MMP2 activity, proliferation, and motility of human aortic smooth muscle cells. Glycobiology 19, 537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noach N., Segev Y., Levi I., Segal S., Priel E. (2007) Modification of topoisomerase I activity by glucose and by O-GlcNAcylation of the enzyme protein. Glycobiology 17, 1357–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vigetti D., Genasetti A., Karousou E., Viola M., Clerici M., Bartolini B., Moretto P., De Luca G., Hascall V. C., Passi A. (2009) Modulation of hyaluronan synthase activity in cellular membrane fractions. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30684–30694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Badi I., Cinquetti R., Frascoli M., Parolini C., Chiesa G., Taramelli R., Acquati F. (2009) Intracellular ANKRD1 protein levels are regulated by 26 S proteasome-mediated degradation. FEBS Lett. 583, 2486–2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Belle A., Tanay A., Bitincka L., Shamir R., O'Shea E. K. (2006) Quantification of protein half-lives in the budding yeast proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13004–13009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fujii N., You L., Xu Z., Uematsu K., Shan J., He B., Mikami I., Edmondson L. R., Neale G., Zheng J., Guy R. K., Jablons D. M. (2007) An antagonist of disheveled protein-protein interaction suppresses β-catenin-dependent tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 67, 573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lazarus M. B., Nam Y., Jiang J., Sliz P., Walker S. (2011) Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature 469, 564–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Slawson C., Copeland R. J., Hart G. W. (2010) O-GlcNAc signaling. A metabolic link between diabetes and cancer? Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 547–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chisalita S. I., Johansson G. S., Liefvendahl E., Bäck K., Arnqvist H. J. (2009) Human aortic smooth muscle cells are insulin-resistant at the receptor level but sensitive to IGF1 and IGF2. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 43, 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Erikstrup C., Pedersen L. M., Heickendorff L., Ledet T., Rasmussen L. M. (2001) Production of hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans from human arterial smooth muscle. The effect of glucose, insulin, IGF-I, or growth hormone. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 145, 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uldry M., Ibberson M., Hosokawa M., Thorens B. (2002) GLUT2 is a high affinity glucosamine transporter. FEBS Lett. 524, 199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thoden J. B., Wohlers T. M., Fridovich-Keil J. L., Holden H. M. (2001) Human UDP-galactose 4-epimerase. Accommodation of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine within the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15131–15136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jokela T. A., Makkonen K. M., Oikari S., Kärnä R., Koli E., Hart G. W., Tammi R. H., Carlberg C., Tammi M. I. (2011) Cellular content of UDP-N-acetylhexosamines controls hyaluronan synthase 2 expression and correlates with O-GlcNAc modification of transcription factors YY1 and SP1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33632–33640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Presto J., Thuveson M., Carlsson P., Busse M., Wilén M., Eriksson I., Kusche-Gullberg M., Kjellén L. (2008) Heparan sulfate biosynthesis enzymes EXT1 and EXT2 affect NDST1 expression and heparan sulfate sulfation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4751–4756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Esko J. D., Selleck S. B. (2002) Order out of chaos. Assembly of ligand-binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 435–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suda T., Kamiyama S., Suzuki M., Kikuchi N., Nakayama K., Narimatsu H., Jigami Y., Aoki T., Nishihara S. (2004) Molecular cloning and characterization of a human multisubstrate-specific nucleotide-sugar transporter homologous to Drosophila fringe connection. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26469–26474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wells L., Vosseller K., Cole R. N., Cronshaw J. M., Matunis M. J., Hart G. W. (2002) Mapping sites of O-GlcNAc modification using affinity tags for serine and threonine post-translational modifications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Magee C., Nurminskaya M., Linsenmayer T. F. (2001) UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Up-regulation in hypertrophic cartilage and role in hyaluronan synthesis. Biochem. J. 360, 667–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weigel P. H., DeAngelis P. L. (2007) Hyaluronan synthases. A decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36777–36781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Camenisch T. D., Spicer A. P., Brehm-Gibson T., Biesterfeldt J., Augustine M. L., Calabro A., Jr., Kubalak S., Klewer S. E., McDonald J. A. (2000) Disruption of hyaluronan synthase-2 abrogates normal cardiac morphogenesis and hyaluronan-mediated transformation of epithelium to mesenchyme. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 349–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Itano N., Sawai T., Yoshida M., Lenas P., Yamada Y., Imagawa M., Shinomura T., Hamaguchi M., Yoshida Y., Ohnuki Y., Miyauchi S., Spicer A. P., McDonald J. A., Kimata K. (1999) Three isoforms of mammalian hyaluronan synthases have distinct enzymatic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25085–25092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hardivillé S., Hoedt E., Mariller C., Benaïssa M., Pierce A. (2010) O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation cycling at Ser-10 controls both transcriptional activity and stability of Δ-lactoferrin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19205–19218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jeffers M., Taylor G. A., Weidner K. M., Omura S., Vande Woude G. F. (1997) Degradation of the Met tyrosine kinase receptor by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 799–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sepp-Lorenzino L., Ma Z., Lebwohl D. E., Vinitsky A., Rosen N. (1995) Herbimycin A induces the 20 S proteasome- and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16580–16587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bonifacino J. S., Weissman A. M. (1998) Ubiquitin and the control of protein fate in the secretory and endocytic pathways. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 19–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hanover J. A., Krause M. W., Love D. C. (2012) Post-translational modifications. Bittersweet memories. Linking metabolism to epigenetics through O-GlcNAcylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 312–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Keembiyehetty C. N., Krzeslak A., Love D. C., Hanover J. A. (2011) A lipid droplet-targeted O-GlcNAcase isoform is a key regulator of the proteasome. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2851–2860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sakaidani Y., Ichiyanagi N., Saito C., Nomura T., Ito M., Nishio Y., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2012) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of mammalian Notch receptors by an atypical O-GlcNAc transferase Eogt1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sakaidani Y., Nomura T., Matsuura A., Ito M., Suzuki E., Murakami K., Nadano D., Matsuda T., Furukawa K., Okajima T. (2011) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine on extracellular protein domains mediates epithelial cell-matrix interactions. Nat. Commun. 2, 583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bond M., Sala-Newby G. B., Newby A. C. (2004) Focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-dependent regulation of S-phase kinase-associated protein-2 (Skp-2) stability. A novel mechanism regulating smooth muscle cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37304–37310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hascall V. C., Majors A. K., De La Motte C. A., Evanko S. P., Wang A., Drazba J. A., Strong S. A., Wight T. N. (2004) Intracellular hyaluronan. A new frontier for inflammation? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1673, 3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xing D., Feng W., Nöt L. G., Miller A. P., Zhang Y., Chen Y. F., Majid-Hassan E., Chatham J. C., Oparil S. (2008) Increased protein O-GlcNAc modification inhibits inflammatory and neointimal responses to acute endoluminal arterial injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295, H335–H342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marsh S. A., Chatham J. C. (2011) The paradoxical world of protein O-GlcNAcylation. A novel effector of cardiovascular (dys)function. Cardiovasc. Res. 89, 487–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Laczy B., Hill B. G., Wang K., Paterson A. J., White C. R., Xing D., Chen Y. F., Darley-Usmar V., Oparil S., Chatham J. C. (2009) Protein O-GlcNAcylation. A new signaling paradigm for the cardiovascular system. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296, H13–H28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.