Background: Tumor microenvironments affect the progression of cancers.

Results: We demonstrated that Th17 cells were accumulated in tumor tissues, and the tumor-derived MIF induced Th17 cell accumulation and had clinical relevance in NPC.

Conclusion: The cytokine MIF regulates intratumoral Th17 cell expansion and has prognostic value for NPC patients.

Significance: The tumor microenvironment influences the clinical prognosis of NPC patients.

Keywords: Cancer, Cellular Immune Response, Chemokines, Chemotaxis, Immunology, Immunosuppression, EBV, MIF, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Tumor Microenvironment

Abstract

The accumulation of an intratumoral CD4+ interleukin-17-producing subset (Th17) of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is a general characteristic in many cancers. The relationship between the percentage of Th17 cells and clinical prognosis differs among cancers. The mechanism responsible for the increasing percentage of such cells in NPC is still unknown, as is their biological function. Here, our data showed an increase of Th17 cells in tumor tissues relative to their numbers in normal nasopharynx tissues or in the matched peripheral blood of NPC patients. Th17 cells in tumor tissue produced more IFNγ than did those in the peripheral blood of matched NPC patients and healthy controls. We observed high levels of CD154, G-CSF, CXCL1, IL-6, IL-8, and macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF) out of 36 cytokines examined in tumor tissue cultures. MIF promoted the generation and recruitment of Th17 cells mediated by NPC tumor cells in vitro; this promoting effect was mainly dependent on the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway and was mediated by the MIF-CXCR4 axis. Finally, the expression level of MIF in tumor cells and in TILs was positively correlated in NPC tumor tissues, and the frequency of MIF-positive TILs was positively correlated with NPC patient clinical outcomes. Taken together, our findings illustrate that tumor-derived MIF can affect patient prognosis, which might be related to the increase of Th17 cells in the NPC tumor microenvironment.

Introduction

Undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC),4 which is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, accounts for over 95% of NPC in China (1–3). NPC tumor progression is usually accompanied by an increase of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and chronic inflammatory response due to the presence on the tumor cells of EBV type II latent antigens, including latent membrane proteins 1 and 2 (LMP1 and LMP2), EBV nuclear protein 1 (EBNA1), and BARF0 (4, 5). The tumor microenvironment includes tumor cells and nonmalignant stromal cells such as fibroblasts, tumor-associated macrophages, and lymphocytes (6). Th17 cells, a CD4+ interleukin-17-producing subset of TILs, have been identified in both humans and mice by the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including the interleukins IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22. Crucial for the development of Th17 cells are the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and transforming growth factor (TGF) β, and the transcription factors STAT3 and retinoic acid-related orphan receptor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γτ (7, 8).

The clinical predictive value of Th17 cells differs among various cancers such as colon, liver, and ovarian cancer (9–11). The origin of Th17 cells and their biological function in human tumor microenvironments are still under investigation. Mechanistic studies have revealed that many cytokines and chemokines, including CCL5, CCL17, CCL20, CCL22, MCP-1, and IL-6, are expressed at a high level within the tumor microenvironment in association with the accumulation of Th17 cells (3, 11–14). However, the mechanistic relationships in NPC between the accumulation of Th17 cells, the cytokines released from tumor environments, and tumorigenesis and progression remain unknown.

In this study, our results indicated an elevated percentage of Th17 cells in the NPC tumor microenvironment. We have shown for the first time that microenvironment-derived macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF) promoted the generation and migration of Th17 cells mediated by tumor cells, and the promotion effect of MIF on the generation and recruitment of Th17 cells was mainly dependent on the mTOR pathway and was mediated by the MIF-CXCR4 axis. Most importantly, the expression of MIF in TILs predicted an improved clinical outcome in NPC. Taken together, our data provide novel evidence that tumor-derived cytokines affect the development of cancer and its prognosis, and they are associated with Th17 cell subset expansion within the tumor microenvironment. These results deepen our understanding of the inflammatory mechanisms involved in NPC progression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Human Samples and Cell Lines

Tumor biopsy tissues and peripheral blood were collected from 21 newly diagnosed NPC patients at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (supplemental Table 1) in 2009 and 2010, and peripheral blood was collected from 21 age-matched healthy individuals. The tumor tissues were divided and cultured for a short period in RPMI 1640 complete medium with a low dose (20 IU/ml) of IL-2 to obtain sufficient lymphocytes, after which the cells were used to generate TILs or in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from blood samples taken from NPC patients and healthy individuals were isolated and then frozen for FACS analyses. One hundred and eight paraffin-embedded tumor specimens from NPC patients were collected in a previous study by our group, and detailed patient information was provided (15). This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration; all patients and healthy controls signed a consent form approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

An EBV-transformed LCL line and the NPC tumor cell lines C666 (EBV+) and CNE2 (EBV−) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The normal nasopharyngeal (NP) cell line NP69 was maintained in keratinocyte-SFM medium (Invitrogen).

Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocyte Culture

TILs were isolated from NPC biopsy tissues and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, and recombinant human IL-2 (300 IU/ml). They were grown using a rapid expansion protocol, as described previously (16).

Flow Cytometry and Antibodies

The expression of T cell markers was analyzed by FACS after surface or intracellular staining with anti-human-specific antibodies conjugated with fluorescent molecules. These human antibodies included anti-CD4, anti-CCR6, anti-IL-17, anti-IFNγ, anti-IL-2, anti-IL-10, anti-IL-4, anti-TGFβ, anti-CCR7, anti-CD45RO, anti-CD45RA, anti-CTLA-4, and anti-GITR. These were conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin, allophycocyanin, or phycoerythrin-Cy7 (BD Biosciences or eBioscience). Recombinant human IL-2, TGFβ, and IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems. Intracellular staining for IL-17 and other cytokines was performed on T cells stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin for 4 h in RPMI 1640 medium, and cytokine secretion was blocked by the addition of brefeldin A (10 μg/ml, Sigma). After washing, cells were stained with anti-CD4, then were fixed and permeabilized with Perm/Fix solution (eBiosciences), and finally were stained intracellularly with anti-IL-17A or with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies for other cytokines. All stained cells were analyzed on an FC500 flow cytometer, and the obtained data were analyzed with CXP software (Beckman Coulter).

Co-culture for Generation of IL-17-producing Cells in Vitro

Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured in T cell medium containing 100 IU/ml IL-2 and 10% FBS at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/well in a 48-well plate and were stimulated with plate-bound OKT3 (1 μg/ml). The naive CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with irradiated NPC tumor cells or irradiated C666 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or pooled MIF-siRNAs at a 1:1 ratio or in the presence of RhIL-1β (25 ng/ml), RhTGFβ (3 ng/ml), or RhIL-1β and RhTGFβ together for 7 days. Half the medium was replaced with fresh medium on days 3 and 6. After 7 days, the percentage of Th17 cells was determined by FACS analysis. The experiments were repeated in triplicate. The RhMIF (R&D Systems), the MIF small molecule antagonist (SR)3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-5-isoxazole acetic acid methyl ester (ISO-1, Sigma), cyclosporin A (CsA, Sigma), or rapamycin (Enzo Life Science) was added to the medium at various concentrations in a subset of the samples as reported before (17, 18).

Cytokine Proteomic Profiling

NPC tumor cell lines (2.5 × 105 per well) or single cell suspensions from collagenase type IV-digested NPC or normal NP tissues were cultured in 6-well plates in 2% FBS RPMI 1640 medium for 48 h. The supernatants were then collected for detection of cytokines. Cytokines in the culture medium were measured using the Human Cytokine Array Panel A (Proteome Profiler; R&D Systems). All cytokine protein array analyses were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Positive controls were paired spots located in the upper left, lower right, and lower left corners of each array.

Migration Assay

Migration assays of TILs from NPC patients were performed using 24-well Transwell chemotaxis plates (5-mm pore size; Corning Costar) as described previously (14). TILs were induced to migrate with supernatants from various cell lines. In some cases, the MIF small molecule antagonist ISO-1(50–100 μm) or neutral anti-CXCR4 antibody (5–10 μm) (19) was added 150 min before the migration assay. The migration of the Th17 cell subset was evaluated based on the percentage of Th17 cells in the inner and outer chambers. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Immunochemistry

MIF immunohistochemistry (IHC) was carried out using a primary monoclonal mouse anti-human MIF antibody (1:100 dilution, ab55445, Abcam), per manufacturer's instructions. The slides were scored independently by two pathologists blinded to the clinicopathological data of the NPC patients. The level of MIF expression in the tumor cells was scored based on staining intensity (score 0–3) and area (score 1–4), as described previously (20); the final expression level was scored as the product of the staining intensity and area scores. The level of MIF expression in lymphocytes was obtained by counting the positively and negatively stained lymphocytes in five separate ×400 high power microscopic fields and calculating the mean percentage of positively stained lymphocytes among the total lymphocytes per field. Mouse anti-human IgG1 (1:200 dilution, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as a negative control in this study.

Statistics

All analyses were carried out with SPSS 13.0. Numerical data are presented as the means ± S.E. A standard two-tailed Student's t test and paired Student's t test were used for comparison of numerical data, and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant in this study. The median of the MIF expression level in tumor cells or in lymphocytes was used as a cutoff subgroup for MIF immunohistochemical variables in our data. The Pearson χ2 test was carried out to assess the relationships among IHC variables. The survival rate was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and tested by log-rank analysis. A Cox regression model was applied for multivariate analyses.

RESULTS

Th17 Cells Were Enriched in Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes

An increase of Th17 cells in the tumor microenvironment is becoming recognized as a general characteristic of cancers (11, 21, 22). We investigated the percentage of Th17 cells in PBMCs and among TILs from 21 newly diagnosed NPC patients and from healthy donors. Fig. 1A shows representative FACS plots of PBMCs from two patients and two controls. The percentage of circulating Th17 cells in 21 NPC patients was significantly lower than that in 21 healthy controls (Fig. 1B; p < 0.001). We also compared the distribution of the Th17 cell subset in tumor tissues versus in peripheral blood from individual NPC patients (Fig. 1C). We found the percentage of Th17 cells was significantly higher in tumor tissues (Fig. 1D, p < 0.001; supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of Th17 cells was decreased in peripheral blood and increased in tumor tissues of NPC patients. A, representative FACS plots of circulating Th17 cells from two NPC patients and two healthy donors (HD). The number displayed is the percentage of the labeled cell population in this study. B, graph of the Th17 cell percentage in PBMCs from NPC patients (n = 21) and healthy donors (n = 21). C, representative FACS plots of circulating and tumor-derived Th17 cells in two matched NPC patients. D, graph of the percentage of Th17 cells among PBMCs and TILs from individual NPC patients (n = 21). Error bars represent S.E. Significance was determined using a χ2 test or paired t test. (*, p < 0.001).

To confirm the increase of Th17 cells in NPC tumor microenvironments, we compared the percentage of Th17 cells in matched sets of samples of peripheral blood and nontumor and tumor tissues from the nasopharynx of NPC patients (Fig. 2, A and B). The percentage of Th17 cells was significantly higher in tumor tissue versus PBMCs or normal tissue and in normal tissue versus PBMCs (Fig. 2C, p < 0.05). The percentage of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells was significantly increased in tumors and peripheral blood relative to normal tissue (Fig. 2D, p < 0.05). The percentage of CD4+ IFNγ-producing cells was not significantly different among the three tissues (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the frequency of Foxp3+ IL-17-producing cells and IFNγ+ IL-17-producing cells in tumor tissues was significantly higher than in normal tissues and PBMCs (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of different lymphocyte subsets in PBMC and in normal nasopharynx (NILs) and nasopharynx tumor tissues (TILs) from individual NPC patients. Representative FACS plots of Th17 cells and Foxp3+ Treg (A) and IFNγ-producing cells in total CD4+ cells from two NPC patients out of five studied (B) are shown. Graphs for total CD4+ cells of the percentage of Th17 cells (C), CD4+ Foxp3+ cells (D), and IFNγ-producing cells in samples from NPC patients (n = 5) (E) are shown. Significance was determined using a paired t test (p < 0.05).

Phenotypic Features and Cytokine Profiles of Circulating and Tumor-infiltrating Th17 Cells in NPC Patients

To explore the biological properties of Th17 cells, we analyzed their phenotypic markers on cells from circulating blood and from the tumor microenvironment. As shown in Fig. 3A, among PBMCs, the Th17 cells were only found among CD45RO+ and CD45RA− memory cells, and the Th17 cells expressed a high level of CCR6 and some CCR7 but lacked expression of CTLA4 and GITR. Among TILs, the Th17 cells were also found only among CD45RO+ and CD45RA− memory cells and expressed a high level of CCR6, a low level of CCR7, some CTLA4, and a low level of GITR.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization and cytokine expression profiles of the Th17 cell subset among PBMCs and TILs from NPC patients. A, T cell surface markers were detected in Th17 cells from NPC patients. T cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin for 4 h, then stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against the markers shown, and analyzed by flow cytometry. B, graph of the percentage of cytokine-secreting Th17 cells among PBMCs and TILs from NPC patients (n = 5) and PBMCs from healthy donors (n = 5). Error bars represent the S.E. Significance was determined by the χ2 test or paired t test. (*, p < 0.001).

We also evaluated the profiles of cytokines, including IL-2, IFNγ, IL-4, IL-10, TGFβ, and GrB, released by the Th17 cell subset among PBMCs and TILs from NPC patients and among PBMCs from healthy controls. All Th17 cells expressed high levels of IL-2 and low levels of IL-4, IL-10, TGFβ, and granzyme B (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the Th17 cells among TILs secreted a large amount of IFNγ, significantly more than from the Th17 cells among the PBMCs of NPC patients or healthy donors (p < 0.001).

Generation and Migration of Th17 Cells Were Promoted by NPC Tumor Cell Lines in Vitro

The mechanism for the accumulation of Th17 cells in the NPC tumor microenvironment has been elusive, although tumor cells and immune cells often contribute to the induction of immune tolerance and inflammation at tumor sites (14, 23–25). To address whether NPC tumor cells could induce the generation or migration of Th17 cells in vitro, we first investigated the induction of Th17 cell differentiation from CD4+ T cells. Purified naive CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with the irradiated NPC cell lines CNE2 (EBV−) or C666 (EBV+), the normal NP cell line NP69, the EBV-transformed lymphoid blast cell line LCL, or in the presence of cytokines. Cells were cultured for 7 days in medium containing IL-2. RhTGFβ, RhIL-1β, or both were included as controls. The resulting percentage of IL-17-producing T cells was evaluated by FACS.

We found that naive CD4+ T cells co-cultured with C666 cells, with cytokine IL-1β, or with a combination of IL-1β and TGFβ exhibited a higher percentage of IL-17-producing cell differentiation in vitro relative to the other co-cultures (Fig. 4, A and B); these experiments were repeated three times.

FIGURE 4.

Generation and migration of Th17 cells mediated by NPC tumor cell lines. A, NPC tumor cell lines induce the differentiation of naive T cells into Th17 cells in vitro. Purified CD4+ naive T cells from healthy donors were stimulated with OKT3 and then co-cultured with the irradiated NPC cell line C666 (EBV+) or CNE2 (EBV−) in IL-2-containing medium for 7 days. The NP69 and LCL lines and the cytokines IL-1β and TGFβ were used as controls. All cultured cells were stained for Foxp3 and IL-17 for FACS analysis after stimulation of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin. The data represent one of three independent experiments. B, mean percentage of cytokine-secreting Th17 cells induced from CD4+ naive T cells from three experiments. C, migration of Th17 cells was increased in response to cultured supernatants from the NPC cell lines C666 and CNE2, relative to that from the normal NP cell line NP69 or with medium alone. The data represent one of three independent experiments. D, mean percentage of cytokine-secreting Th17 cells in the inner well and outer well after migration induced by supernatants from NP69, C666, or CNE2 cells from three experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. Significance was determined by the χ2 test or paired t test. (*, p < 0.05).

Next, we examined whether the supernatants of NPC tumor cells could attract the migration of Th17 cells from TILs or PBMCs (Fig. 4C). A higher percentage of Th17 cells was present in the outer well of a Transwell assay of TILs cultured with supernatants from the NPC C666 (p < 0.05) or CNE2 cell lines, indicating that the cytokines released from NPC cell lines attracted Th17 cells more strongly than those from normal NP cells or media alone (Fig. 4D). The supernatants from C666 and CNE2 cells also attracted the migration of Th17 cells from a PBMC population (data not shown). Collectively, these data suggest that NPC tumor-derived cytokines and chemokines may induce Th17 cell generation and chemotaxis.

High Levels of MIF and Other Cytokines Released from NPC Tumor Tissues and Cell Lines

To explore whether tumor-derived cytokines may affect NPC tumor microenvironments, we evaluated cytokine profiles of nontumor and tumor tissues from an NPC patient and of the NPC cell lines C666 (EBV+) and CNE2 (EBV−), using a Proteome Profiler Array as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The 36 analyzed cytokines are listed in Table 1. CD154, G-CSF, CXCL1, CD54, IL-6, IL-8, MIF, serpin E1, and SDF-1 were detectable in one or more of the culture supernatants, as shown in Table 1. G-CSF, CXCL1, IL-6, IL-8, MIF, and serpin E1 were detectable in the supernatant of normal NP tissues. Overall, MIF was the only cytokine found at a high level in all the supernatants (supplemental Fig. S2).

TABLE 1.

Cytokines and chemokines released from NPC tumor cell lines, NPC tissue, or normal NP tissue in vitro

| Cytokine | Alternative nomenclature | C666 (EBV+) | CNE2 (EBV−) | NPC tissue | Normal NP tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5a | Complement component 5a | − | − | − | − |

| CD154 | CD40 ligand | + | + | + | − |

| G-CSF | CSFβ, CSF-3 | − | − | + | + |

| GM-CSF | CSFα, CSF-2 | − | − | − | − |

| GROα | CXCL1 | − | − | + | + |

| I-309 | CCL1 | − | − | − | − |

| CD54 | sICAM-1 | + | − | − | − |

| IFN-γ | Type II IFN | − | − | − | − |

| IL-1α | IL-F1 | − | − | − | − |

| IL-1β | IL-1F2 | − | − | − | − |

| IL-1ra | IL-F3 | − | − | − | − |

| IL-2 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-4 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-5 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-6 | − | − | + | + | |

| IL-8 | CXCL8 | − | − | + | + |

| IL-10 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-12p70 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-13 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-16 | LCF | − | − | − | − |

| IL-17 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-17E | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-23 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-27 | − | − | − | − | |

| IL-32α | − | − | − | − | |

| IP-10 | CXCL10 | − | − | − | − |

| I-TAC | CXCL11 | − | − | − | − |

| MCP-1 | CCL2 | − | − | − | − |

| MIF | GIF, DER6 | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| MIP-1α | CCL3 | − | − | − | − |

| MIP-1β | CCL4 | − | − | − | − |

| Serpin E1 | PAI-1 | − | + | − | + |

| RANTES | CCL5 | − | − | − | − |

| SDF-1 | CXCL12 | + | + | − | − |

| TNFα | TNFSF 1A | − | − | − | − |

| sTREM-1 | − | − | − | - |

MIF Promotes the Generation and Migration of Th17 Cells Mediated by Tumor Cells

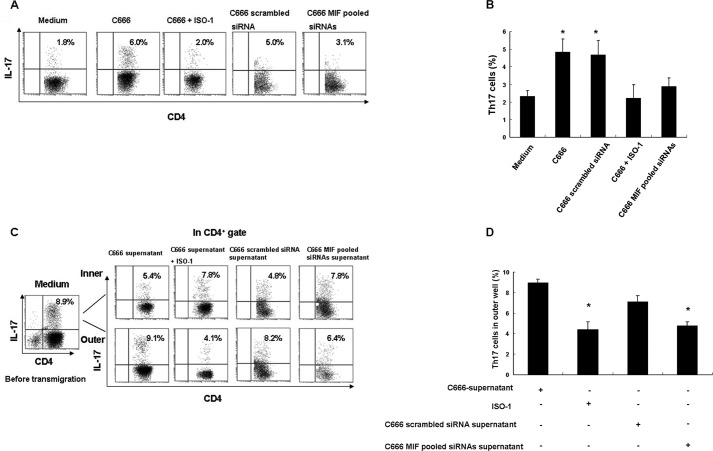

Based on the high expression levels of MIF in the NPC tumor microenvironment and on reports that MIF may be involved in the generation of IL-17-producing cells in mice (26, 27), we investigated whether MIF is involved in the generation and recruitment of Th17 cells in tumors. In a culture of CD4+ naive T cells with C666 NPC cells, the presence of the MIF small molecule inhibitor ISO-1 reduced the generation of Th17 cells (p < 0.05); in addition, the generation of Th17 cells also noticeably decreased when CD4+ naive T cells were co-cultured with C666 transfected with siRNAs against MIF (Fig. 5, A and B; supplemental Fig. S3). In a Transwell chemotaxis assay, ISO-1 and the supernatants from MIF-siRNA-transfected C666 cells noticeably decreased the migration of Th17 cells to the outer well (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5, C and D; supplemental Fig. S3). The ability of MIF directly to promote the migration of Th17 cells in an NPC TIL population was also demonstrated (supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 5.

Role of MIF in the generation and migration of Th17 cells. A, generation of Th17 cells was decreased by the presence of either ISO-1 or siRNA against MIF. B, graph of IL-17-positive cells as a percentage of Th17 cells; data are from three independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E.; *, p < 0.05. C, ISO-1 noticeably inhibited the migration of Th17 cells exposed to the supernatant of the C666 cell line, and the migration of Th17 cells exposed to supernatant from MIF-siRNA-treated C666 cells was also decreased; data are representative of three independent experiments. D, percentage of Th17 cells migrating to the outer well; data are from three independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E.. *, p < 0.05. Significance was determined by performing paired t test.

MIF-promoting Generation and Migration of Th17 Cells Are Mainly Dependent on mTOR Pathway and Mediated by MIF-CXCR4 Axis

It has recently been reported that the transcription factor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γτ, the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), and the transcription factor STAT3 were the key molecules in the induction and differentiation of human Th17 cells (28–30) and that MIF is involved in the mTOR pathway in CD4+ T cell proliferation under hypoxia (31). Here, our goal was to investigate the roles of NFAT and mTOR signaling pathways during the promoting effect of MIF on the Th17 cell expansion mediated by NPC tumor cells. In this study, as described above, purified naive CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with the irradiated NPC cell line C666 or in the presence of exogenous RhMIF in IL-2 medium for 7 days; rapamycin and CsA were present in a subset of samples; the cytokines RhTGFβ plus RhIL-6 and RhIL-23 were used as controls. The presence of CsA and rapamycin could noticeably reduce the percentage of TGFβ/IL-6/IL-23-stimulated IL-17-producing cells from 7.5 to 1.7 and 3.5%, respectively. Similarly, the presence of CsA and rapamycin reduced the generation of IL-17-producing cells mediated by NPC cell line C666 and exogenous RhMIF from 5.0 to 2.9 and 1.8%, respectively (Fig. 6A). Therefore, both CsA and rapamycin inhibited the generation of Th17 cells mediated by cytokines in vitro, and the inhibitory effect of CsA was stronger than that of rapamycin. However, rapamycin more effectively inhibited the generation of Th17 cells mediated by C666 and exogenous RhMIF, in contrast to CsA (data not shown). Collectively, these results suggested that the promotion effect of MIF on the generation of Th17 cells was mainly mediated by the mTOR pathway, as shown in Fig. 6B.

FIGURE 6.

Signaling pathways of MIF involved in the generation and migration of Th17 cells. A, generation of Th17 cells induced by cytokines or C666 cells and MIF was decreased by the presence of rapamycin or CsA in the culture media at different levels; data are representative of three independent experiments. B, MIF promoting the generation of Th17 cells in vitro was dependent on mTOR signaling pathway. C, expression of CXCR4 on IL-17-positive and -negative cell population. D, specific neutralizing antibody against CXCR4 significantly inhibited the migration of Th17 cells exposed to the supernatant of the C666 cell line; data are representative of three independent experiments. E, percentage of Th17 cells migrating to the outer well; data are from three independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. *, p < 0.05. Significance was determined by performing paired t test.

CD74 and CXCR4 are the key receptors of MIF, and the CXCR4 is one of the major chemokine receptors expressed on the Th17 cell subset (32, 33). Therefore, we examined the CXCR4 expression in the Th17 cell subset of TILs and found that Th17 cells expressed CXCR4 (Fig. 6C). We then performed an experiment in a Transwell system to determine whether the neutral antibody blocking CXCR4 could abort the effect of MIF on the migration of Th17 cells in vitro. As shown in Fig. 6, D and E, the supernatants of C666 cell lines enhanced the migration of Th17 cells relative to control medium, which was consistent with Fig. 4C. However, the migration of Th17 cells was significantly inhibited when the different concentrations of the neutral antibody against CXCR4 were added in the supernatants of the C666 cell line.

Expression Level of MIF in Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes Is an Independent Prognostic Factor for NPC Outcome

We examined the expression of MIF by immunohistochemistry in paraffin-embedded tumor specimens from 108 NPC patients. MIF could be localized to the cytoplasm of the tumor cells and to the cytoplasm of lymphocytes around tumor tissues (Fig. 7A). Thirty one of 108 tumor specimens showed no MIF expression in the tumor cells; the others displayed varied levels of MIF expression. The MIF-positive lymphocytes per high light microscope field in the 108 NPC tumor specimens ranged from 0 to 99% of total lymphocytes. Statistical analysis of the 108 specimens demonstrated that the percentage of MIF-positive lymphocytes was positively correlated with the level of MIF expression in the tumor cells (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Increased expression of MIF in TILs predicts improved patient survival. A, immunohistochemical staining shows varied intensities of MIF expression in the cytoplasm of tumor cells or tumor-associated lymphocytes (×40). B, percentage of MIF-positive lymphocytes around tumor cells was increased with the expression levels of MIF in tumor cells (R = 0.69, p < 0.0001). C and D, samples from NPC patients (n = 108) were divided into two groups based on positive or negative expression of MIF in NPC tumor cells. Disease-free survival and overall survival were significantly increased with increased expression of MIF in TILs, as displayed in Kaplan-Meier plots of overall survival.

We divided the NPC patients into subgroups based on the median expression level of MIF in tumor cells or lymphocytes. A high level of MIF expression in lymphocytes predicted a positive clinical outcome for NPC patients (Fig. 7, C and D). Multivariate analysis indicated that MIF was an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival and overall survival of NPC patients (supplemental Table 2), but we found no association between MIF expression in tumor cells or lymphocytes and clinicopathological characteristics (supplemental Table 3) and no association between MIF expression in tumors and NPC patient survival (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The idea that the immune system can control cancer has been suggested for over a century. In recent years, the “cancer immunoediting” hypothesis has been proposed, based on the 2001 discovery that the immune system can control the quality and quantity of cancer (6). The intratumor immune responses in humans, such as the distribution of special TIL subsets and tumor-derived cytokines, could be used to predict patient prognosis (6, 34). In recent years, the distribution and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in cancer have been studied (10, 11, 22, 35). The accumulation of Th17 cells in tumor tissues has been found to be a feature of many cancers, but the percentage of Th17 cells among the circulating lymphocytes changes based on disease progression and cancer type (10, 11, 36–38).

In this study, we determined the distribution and functional features of Th17 cells in peripheral blood and tumor tissues from nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients, and we investigated the ability of tumor cells to promote the generation and migration of this subset. We also analyzed the cytokines and chemokines released from the NPC tumor microenvironment and determined the clinical relevance of MIF expression in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

In 21 patients with NPC (19/21 in late-disease stage, supplemental Table S1), we found a decreased percentage of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood of NPC patients relative to that of healthy individuals. Moreover, a larger percentage of Th17 cells was found among TILs relative to the peripheral blood or normal nasopharynx tissues of NPC patients. It has been reported that the proportion of circulating Treg and Th17 cells is increased in early stage patients, although the percentage of circulating Th17 cells decreased and that of circulating Treg cells increased in advanced patients with gastric cancer (22). Our results also showed a decreased percentage of Th17 cells in PBMCs from NPC patients (most at an advanced disease stage) relative to healthy controls.

The clinical relevance of Th17 cells has been reported for many kinds of cancers, but the results have sometimes been opposed. For example, the number of Th17 cells positively predicted the clinical outcome for ovarian cancer patients but negatively predicted the clinical outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (10, 11). In a previous study, we could not determine the relationship between the density of Th17 cells and the clinical outcome in NPC patients (39).

The biological function of the Th17 cell subset in cancer remains largely unknown. In this study, we analyzed the general characteristics and functional features of the Th17 cell subset in PBMCs and TILs. Our results showed that Th17 cells expressed high levels of the chemokine receptor CCR6 and some CCR7. Most of the Th17 cells came from the CD45RO+ memory T cell population. Th17 cells from NPC patients expressed some CTLA4 but no GITR. These results are consistent with observations in other cancers and provide evidence that Th17 cells can home to tumor tissues (8, 14, 35, 40). Cytokine profiles indicated that Th17 cells secrete high levels of IL-2 and low levels of IL-4, TGFβ, and GrB. Interestingly, the Th17 cells in TILs secreted significantly higher levels of IFNγ than did PBMCs from NPC patients and healthy controls (Fig. 3B). This result indicates that Th17 cells may have an anti-tumor function in NPC tumor tissues by secreting Th1 cytokines such as IFNγ and IL-2, similar to Th17 cells in ovarian cancer (11).

The increased percentage of Th17 cells in tumor tissues is associated with cytokines and chemokines released from tumor microenvironments (14, 23, 41–44). This study shows for the first time that the EBV+ C666 cells co-cultured with CD4+ naive T cells promoted the generation of Th17 cells, in comparison with the CNE2 (EBV−), LCL, or NP69 cells. Furthermore, the supernatants from C666 and CNE2 cultures could promote the migration of Th17 cells in vitro.

Six cytokines were found in the culture medium of NPC tumor tissues, with MIF being found in the greatest amount. MIF, which is often secreted by naive CD4+ T cells, can stimulate IL-17-producing cells in the lymph nodes of mice (27, 45). However, the role of MIF in expanding the Th17 cell subset in human tumors is not known. Our data showed that MIF was involved in the generation and migration of Th17 cells in NPC and that this activity was blocked by the MIF inhibitor ISO-1 or by siRNAs targeting MIF-transfected NPC cell lines in vitro. Furthermore, our results for the first time indicated that the effect of MIF on the generation and recruitment of Th17 cells was mainly dependent on the mTOR signaling pathway and mediated by the MIF-CXCR4 axis but independent of NFAT pathway. These results were consistent with recent reports that the effect of MIF on stimulating the expression of IL-17 in lymph node cells of mice was dependent on the MAPK-JAK2/STAT3 pathway but not the NFκβ or NFAT pathway (27, 46). Others also have found that MIF can up-regulate IL-6, which was also involved in the generation of Th17 cells, IL-8, and TNFα in patients with Vibrio vulnificus (47).

Overexpression of MIF has been identified in tumor cells of many types of cancers, including NPC (48–51). Here, we detected the expression of MIF in NPC tumor tissues by IHC in paraffin-embedded sections from 108 patients. MIF was expressed in tumor cells and in lymphocytes around NPC tumor tissues, and there was a correlation between the expression levels of MIF in tumor cells and the MIF-positive lymphocytes in tumor tissues. Moreover, we found that high expression of MIF in TILs was associated with improved NPC patient outcome, and MIF was an independent prognostic factor for NPC patients by multivariate analysis.

High expression of MIF in NPC tumor tissues is associated with increased microvessels and increased lymph node metastasis of NPC tumors, whereas the angiogenesis and lymph node status exhibited in relation to patient survival has been identified as an independent prognostic factor of NPC by multivariate analysis (52). MIF is overexpressed in human rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines, and it prevents rhabdomyosarcoma cells from responding to chemoattractants secreted outside of the growing tumor (e.g. SDF-1), thereby preventing the release of cells into the circulation. Moreover, MIF inhibits the recruitment of cancer-associated fibroblasts to growing tumors in an CXCR2/CD74-dependent manner; therefore, therapeutic inhibition of MIF in rhabdomyosarcoma may accelerate metastasis and tumor growth (50). In drug-resistant human colon cancers, the MIF-CXCR4 axis mediates the invasive and metastatic phenotype of the cancer (53, 54), but MIF does not play a prominent role in tumor progression in gastric adenocarcinomas (55). Collectively, these findings indicate that MIF has multiple functions in tumor microenvironments. The data obtained in this study are the first indicating a protective function of MIF in the tumor microenvironment and involvement in promoting the NPC tumor cell-mediated induction and migration of Th17 cells.

In conclusion, our data provide novel evidence of the accumulation of Th17 cells in the NPC tumor microenvironment and of the biological functions of the Th17 cells in NPC tumor tissues, such as secretion of Th1 cytokines. We have shown for the first time that overexpression of MIF in the tumor microenvironment is involved in the induction and migration of human Th17 cells in vitro, which mainly depends on the mTOR pathway and is mediated by the MIF-CXCR4 axis. Finally, we found that there is a clinical relevance to tumor-derived MIF expression levels in NPC patients. These data provide novel insights into inflammatory responses in NPC tumor progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rong-Fu Wang (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) for valuable comments for this manuscript and members of the Zeng laboratory for helpful discussions. We also thank David Nadziejka of Grand Rapids, MI, for critical reading and technical editing of the manuscript.

This work was supported by General Program Grants 30872981 and 81172164 (to J. L.), State Key Program Grant 81030043 (to C.-N. Q.) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation Grant 0151008901000156 (to J. L.), National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) Grant 20060102A4002 (to C.-N. Q.), and Major State Basic Research Program (973 Project) of China Grant 2006CB910104 (to Y. X. Z.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4, Tables S1–S3, and Methods.

- NPC

- nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Th17 cells

- CD4+ interleukin-17-producing cells

- MIF

- macrophage inhibitory factor

- TIL

- tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- ISO-1

- (SR)3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-5-isoxazole acetic acid methyl ester

- CsA

- cyclosporin A

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- NFAT

- nuclear factor of activated T cell

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- NP

- nasopharyngeal

- EBV

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Rh

- recombinant human.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pathmanathan R., Prasad U., Chandrika G., Sadler R., Flynn K., Raab-Traub N. (1995) Undifferentiated, nonkeratinizing, and squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Variants of Epstein-Barr virus-infected neoplasia. Am. J. Pathol. 146, 1355–1367 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cao S. M., Simons M. J., Qian C. N. (2011) The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin. J. Cancer 30, 114–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wee J. T., Ha T. C., Loong S. L., Qian C. N. (2010) Is nasopharyngeal cancer really a “Cantonese cancer”? Chin. J. Cancer 29, 517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Niedobitek G., Agathanggelou A., Nicholls J. M. (1996) Epstein-Barr virus infection and the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Viral gene expression, tumor cell phenotype, and the role of the lymphoid stroma. Semin. Cancer Biol. 7, 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasef M. A., Ferlito A., Weiss L. M. (1997) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, with emphasis on its relationship to Epstein-Barr virus. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 106, 348–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schreiber R. D., Old L. J., Smyth M. J. (2011) Cancer immunoediting. Integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 331, 1565–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu H., Kortylewski M., Pardoll D. (2007) Cross-talk between cancer and immune cells. Role of STAT3 in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang L., Yi T., Kortylewski M., Pardoll D. M., Zeng D., Yu H. (2009) IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1457–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lv L., Pan K., Li X. D., She K. L., Zhao J. J., Wang W., Chen J. G., Chen Y. B., Yun J. P., Xia J. C. (2011) The accumulation and prognosis value of tumor-infiltrating IL-17-producing cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 6, e18219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang J. P., Yan J., Xu J., Pang X. H., Chen M. S., Li L., Wu C., Li S. P., Zheng L. (2009) Increased intratumoral IL-17-producing cells correlate with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J. Hepatol. 50, 980–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kryczek I., Banerjee M., Cheng P., Vatan L., Szeliga W., Wei S., Huang E., Finlayson E., Simeone D., Welling T. H., Chang A., Coukos G., Liu R., Zou W. (2009) Phenotype, distribution, generation, and functional and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in the human tumor environments. Blood 114, 1141–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dürr C., Pfeifer D., Claus R., Schmitt-Graeff A., Gerlach U. V., Graeser R., Krüger S., Gerbitz A., Negrin R. S., Finke J., Zeiser R. (2010) CXCL12 mediates immunosuppression in the lymphoma microenvironment after allogeneic transplantation of hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res. 70, 10170–10181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu J., Zhang N., Li Q., Zhang W., Ke F., Leng Q., Wang H., Chen J. (2011) Tumor-associated macrophages recruit CCR6+ regulatory T cells and promote the development of colorectal cancer via enhancing CCL20 production in mice. PLoS One 6, e19495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Su X., Ye J., Hsueh E. C., Zhang Y., Hoft D. F., Peng G. (2010) Tumor microenvironments direct the recruitment and expansion of human Th17 cells. J. Immunol. 184, 1630–1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Y. L., Li J., Mo H. Y., Qiu F., Zheng L. M., Qian C. N., Zeng Y. X. (2010) Different subsets of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with NPC progression in different ways. Mol. Cancer 9, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dudley M. E., Wunderlich J. R., Shelton T. E., Even J., Rosenberg S. A. (2003) Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J. Immunother. 26, 332–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deleted in proof

- 18. Kopf H., de la Rosa G. M., Howard O. M., Chen X. (2007) Rapamycin inhibits differentiation of Th17 cells and promotes generation of FoxP3+ T regulatory cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 7, 1819–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baribaud F., Edwards T. G., Sharron M., Brelot A., Heveker N., Price K., Mortari F., Alizon M., Tsang M., Doms R. W. (2001) Antigenically distinct conformations of CXCR4. J. Virol. 75, 8957–8967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wee A., Teh M., Raju G. C. (1994) Clinical importance of p53 protein in gallbladder carcinoma and its precursor lesions. J. Clin. Pathol. 47, 453–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The Selected Cancers Cooperative Study Group (1990) The association of selected cancers with service in the United States military in Vietnam. III. Hodgkin disease, nasal cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, and primary liver cancer. Arch. Intern. Med. 150, 2495–2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maruyama T., Kono K., Mizukami Y., Kawaguchi Y., Mimura K., Watanabe M., Izawa S., Fujii H. (2010) Distribution of Th17 cells and FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, tumor-draining lymph nodes and peripheral blood lymphocytes in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 101, 1947–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyahara Y., Odunsi K., Chen W., Peng G., Matsuzaki J., Wang R. F. (2008) Generation and regulation of human CD4+ IL-17-producing T cells in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15505–15510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moo-Young T. A., Larson J. W., Belt B. A., Tan M. C., Hawkins W. G., Eberlein T. J., Goedegebuure P. S., Linehan D. C. (2009) Tumor-derived TGF-β mediates conversion of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in a murine model of pancreas cancer. J. Immunother. 32, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shen X., Li N., Li H., Zhang T., Wang F., Li Q. (2010) Increased prevalence of regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment and its correlation with TNM stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 136, 1745–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Addis M. F., Tanca A., Pagnozzi D., Crobu S., Fanciulli G., Cossu-Rocca P., Uzzau S. (2009) Generation of high quality protein extracts from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Proteomics 9, 3815–3823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stojanović I., Cvjetićanin T., Lazaroski S., Stosić-Grujicić S., Miljković D. (2009) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor stimulates interleukin-17 expression and production in lymph node cells. Immunology 126, 74–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harris T. J., Grosso J. F., Yen H. R., Xin H., Kortylewski M., Albesiano E., Hipkiss E. L., Getnet D., Goldberg M. V., Maris C. H., Housseau F., Yu H., Pardoll D. M., Drake C. G. (2007) Cutting edge. An in vivo requirement for STAT3 signaling in TH17 development and TH17-dependent autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 179, 4313–4317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Delgoffe G. M., Kole T. P., Zheng Y., Zarek P. E., Matthews K. L., Xiao B., Worley P. F., Kozma S. C., Powell J. D. (2009) The mTOR kinase differentially regulates effector and regulatory T cell lineage commitment. Immunity 30, 832–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Radojcic V., Pletneva M. A., Yen H. R., Ivcevic S., Panoskaltsis-Mortari A., Gilliam A. C., Drake C. G., Blazar B. R., Luznik L. (2010) STAT3 signaling in CD4+ T cells is critical for the pathogenesis of chronic sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease in a murine model. J. Immunol. 184, 764–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaber T., Schellmann S., Erekul K. B., Fangradt M., Tykwinska K., Hahne M., Maschmeyer P., Wagegg M., Stahn C., Kolar P., Dziurla R., Löhning M., Burmester G. R., Buttgereit F. (2011) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor counter-regulates dexamethasone-mediated suppression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α function and differentially influences human CD4+ T cell proliferation under hypoxia. J. Immunol. 186, 764–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schober A., Bernhagen J., Weber C. (2008) Chemokine-like functions of MIF in atherosclerosis. J. Mol. Med. 86, 761–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lim H. W., Lee J., Hillsamer P., Kim C. H. (2008) Human Th17 cells share major trafficking receptors with both polarized effector T cells and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 180, 122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swann J. B., Vesely M. D., Silva A., Sharkey J., Akira S., Schreiber R. D., Smyth M. J. (2008) Demonstration of inflammation-induced cancer and cancer immunoediting during primary tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 652–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang C., Kang S. G., Lee J., Sun Z., Kim C. H. (2009) The roles of CCR6 in migration of Th17 cells and regulation of effector T-cell balance in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2, 173–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu J., Duan Y., Cheng X., Chen X., Xie W., Long H., Lin Z., Zhu B. (2011) IL-17 is associated with poor prognosis and promotes angiogenesis via stimulating VEGF production of cancer cells in colorectal carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 407, 348–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ratajczak P., Janin A., Peffault de Latour R., Leboeuf C., Desveaux A., Keyvanfar K., Robin M., Clave E., Douay C., Quinquenel A., Pichereau C., Bertheau P., Mary J. Y., Socié G. (2010) Th17/Treg ratio in human graft-versus-host disease. Blood 116, 1165–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tosolini M., Kirilovsky A., Mlecnik B., Fredriksen T., Mauger S., Bindea G., Berger A., Bruneval P., Fridman W. H., Pagès F., Galon J. (2011) Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, th2, treg, and th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 71, 1263–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang Y. L., Li J., Mo H. Y., Qiu F., Zheng L. M., Qian C. N., Zeng Y. X. (2010) Different subsets of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with NPC progression in different ways. Mol. Cancer 9, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zou W., Restifo N. P. (2010) T(H)17 cells in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 248–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Evans H. G., Gullick N. J., Kelly S., Pitzalis C., Lord G. M., Kirkham B. W., Taams L. S. (2009) In vivo activated monocytes from the site of inflammation in humans specifically promote Th17 responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6232–6237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kimura A., Naka T., Kishimoto T. (2007) IL-6-dependent and -independent pathways in the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12099–12104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paintlia M. K., Paintlia A. S., Singh A. K., Singh I. (2011) Synergistic activity of interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α enhances oxidative stress-mediated oligodendrocyte apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 116, 508–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye Z. J., Zhou Q., Gu Y. Y., Qin S. M., Ma W. L., Xin J. B., Tao X. N., Shi H. Z. (2010) Generation and differentiation of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in malignant pleural effusion. J. Immunol. 185, 6348–6354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park S. K., Cho M. K., Park H. K., Lee K. H., Lee S. J., Choi S. H., Ock M. S., Jeong H. J., Lee M. H., Yu H. S. (2009) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor homologs of anisakis simplex suppress Th2 response in allergic airway inflammation model via CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cell recruitment. J. Immunol. 182, 6907–6914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bachand A. M., Mundt K. A., Mundt D. J., Montgomery R. R. (2010) Epidemiological studies of formaldehyde exposure and risk of leukemia and nasopharyngeal cancer. A meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 40, 85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chuang C. C., Chuang Y. C., Chang W. T., Chen C. C., Hor L. I., Huang A. M., Choi P. C., Wang C. Y., Tseng P. C., Lin C. F. (2010) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor regulates interleukin-6 production by facilitating nuclear factor-κB activation during Vibrio vulnificus infection. BMC Immunol. 11, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen Y. C., Zhang X. W., Niu X. H., Xin D. Q., Zhao W. P., Na Y. Q., Mao Z. B. (2010) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a direct target of HBP1-mediated transcriptional repression that is overexpressed in prostate cancer. Oncogene 29, 3067–3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krockenberger M., Engel J. B., Kolb J., Dombrowsky Y., Häusler S. F., Kohrenhagen N., Dietl J., Wischhusen J., Honig A. (2010) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression in cervical cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 136, 651–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tarnowski M., Grymula K., Liu R., Tarnowska J., Drukala J., Ratajczak J., Mitchell R. A., Ratajczak M. Z., Kucia M. (2010) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is secreted by rhabdomyosarcoma cells, modulates tumor metastasis by binding to CXCR4 and CXCR7 receptors, and inhibits recruitment of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 1328–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fang W., Li X., Jiang Q., Liu Z., Yang H., Wang S., Xie S., Liu Q., Liu T., Huang J., Xie W., Li Z., Zhao Y., Wang E., Marincola F. M., Yao K. (2008) Transcriptional patterns, biomarkers, and pathways characterizing nasopharyngeal carcinoma of Southern China. J. Transl. Med. 6, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liao B., Zhong B. L., Li Z., Tian X. Y., Li Y., Li B. (2010) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor contributes angiogenesis by up-regulating IL-8 and correlates with poor prognosis of patients with primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 102, 844–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nishihira J., Ishibashi T., Fukushima T., Sun B., Sato Y., Todo S. (2003) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Its potential role in tumor growth and tumor-associated angiogenesis. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 995, 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takahashi N., Nishihira J., Sato Y., Kondo M., Ogawa H., Ohshima T., Une Y., Todo S. (1998) Involvement of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in the mechanism of tumor cell growth. Mol. Med. 4, 707–714 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xia H. H., Yang Y., Chu K. M., Gu Q., Zhang Y. Y., He H., Wong W. M., Leung S. Y., Yuen S. T., Yuen M. F., Chan A. O., Wong B. C. (2009) Serum macrophage migration-inhibitory factor as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer. Cancer 115, 5441–5449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]