Abstract

A series of reports have recently appeared using tensor based morphometry statistically-defined regions of interest, Stat-ROIs, to quantify longitudinal atrophy in structural MRIs from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). This commentary focuses on one of these reports, Hua et al. (2010), but the issues raised here are relevant to the others as well. Specifically, we point out a temporal pattern of atrophy in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment whereby the majority of atrophy in two years occurs within the first 6 months, resulting in overall elevated estimated rates of change. Using publicly-available ADNI data, this temporal pattern is also found in a group of identically-processed healthy controls, strongly suggesting that methodological bias is corrupting the measures. The resulting bias seriously impacts the validity of conclusions reached using these measures; for example, sample size estimates reported by Hua et al. (2010) may be underestimated by a factor of five to sixteen.

Keywords: Nonlinear image registration, Regional change quantification, MRI biomarkers, Clinical trials, Bias, Alzheimer’s disease

Commentary

We have read with interest a series of publications using tensor based morphometry (TBM) measures of longitudinal change estimated from structural MRI available through the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): Hua et al. (2008a,b, 2009, 2010); Ho et al. (2010); Kohannim et al. (2010); Beckett et al. (2010); among others. Formed in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the Food and Drug Administration, private pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations, ADNI is a multisite initiative that collects serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), genetics, biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessments to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The Principal Investigator of this initiative is Michael W. Weiner, of the Veterans Administration Medical Center and University of California-San Francisco.

This commentary focuses on Hua et al. (2010), hereinafter Hua et al., but the results we present also impact the validity of conclusions reached in these other ADNI reports. Specifically, we provide statistical evidence that longitudinal trajectories of brain atrophy for AD and MCI subjects, quantified in a statistically-defined template region, the temporal lobe Stat-ROI, are systematically biased upward for all follow-up timepoints. We further demonstrate that longitudinal TBM-measures from a healthy control (HC) group, publicly available at http://www.loni.ucla.edu, provide an important check on the plausibility of longitudinal trajectories of the TBM-derived atrophy in AD and MCI subjects.

Though diagnosing the precise source of bias in Hua et al. is beyond the scope of this commentary, we make some general remarks here as to how it may have arisen. Bias can enter image-based measurements of change if there is asymmetry with respect to the images in the methodology (Christensen, 1999; Ashburner et al., 2000). Though methods of image registration designed to be unbiased (Leow et al., 2007; Yanovsky et al., 2009) were employed in Hua et al., asymmetry in longitudinal registration of subject follow up to baseline scans cannot be ruled out. Any small bias that may have arisen at this stage (Yushkevich et al., 2010) might then be amplified by use of the Stat-ROI, where voxels of highest change are preferentially selected. Bias in estimates of change is therefore potentially more pronounced in methods that rely on Stat-ROIs than in methods that use predefined subject-specific tissue ROIs.

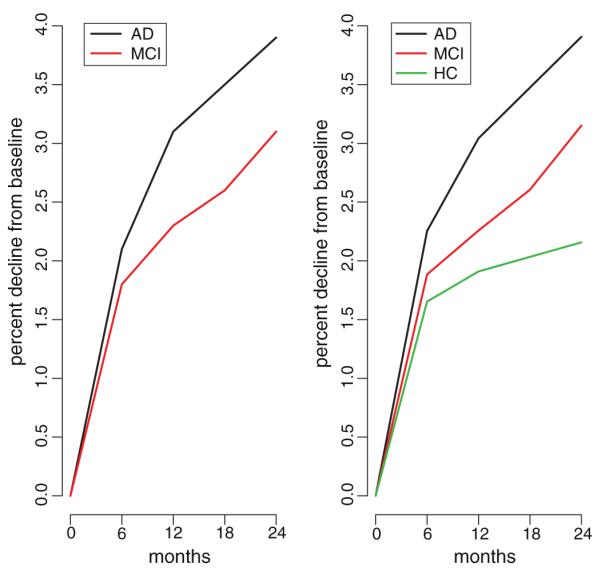

While we can only speculate on its source, the statistical evidence for such bias is unequivocal and seriously undermines the validity of conclusions reached in Hua et al. and in other reports using current TBM-derived measures of longitudinal brain atrophy, notably Cummings (2010), Jack et al. (2010), and Beckett et al. (2010). In particular, Hua et al. endeavor to compute sample sizes necessary in a clinical trial for detecting with 80% and 90% power a 25% reduction in mean annual rate of various TBM-derived measures of atrophy in AD and MCI subjects, using rates of atrophy computed as percent change from baseline at 6, 12, and 24 months for 91 AD subjects and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months for 189 MCI subjects. We reproduce the results from this report for the temporal lobe Stat-ROI of AD and MCI subjects in the left panel of Fig. 1 (data obtained from Hua et al. Fig. 3, p. 68). A higher mean annual rate of atrophy, but with a fixed variance in the rate, translates into a smaller sample size needed to detect a 25% reduction in the rate of atrophy for a given power, as can be seen using the formula on p. 66 of Hua et al. Based on their estimated mean annual rates of atrophy in AD and MCI subjects in the ADNI data, Hua et al. conclude that the Stat-ROI measures provide higher effect sizes and dramatically lower sample size requirements than the most commonly-applied clinical measures of cognition and dementia. Indeed, the Stat-ROI measures appear to be very powerful compared with all other imaging measures (Cummings, 2010; Beckett et al., 2010). This result has potentially significant practical implications, since conclusions reached from ADNI TBM-based Stat-ROI trajectories may be an influential guide to AD researchers in deciding which measures to use in clinical trials of treatments and how large of a sample size to recruit to obtain adequate power. We reproduce the sample size requirements for 80% and 90% power for TBM-derived Stat-ROI in Table 1 (data taken from Hua et al. Table 1, p. 68).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative atrophy for TBM-derived Stat-ROI. Left panel: Mean percent change in TBM-derived Stat-ROI measures for 91 AD and 189 MCI subjects in ADNI (data taken from Hua et al. (2010) Fig. 3 p. 68). Right panel: Mean percent change in TBM-derived Stat-ROI measures for 81 AD, 198 MCI, and 160 HC subjects in ADNI (data publicly-available at http://www.loni.ucla.edu, current as of May 5, 2010).

Table 1.

Sample size estimates for TBM-derived Stat-ROI.

| Uncorrected | Corrected | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 6 months | n80 | 80 | 425 |

| n90 | 107 | 569 | ||

| 12 months | n80 | 46 | – | |

| n90 | 62 | – | ||

| 18 months | n80 | – | 175 | |

| n90 | – | 234 | ||

| 24 months | n80 | 39 | – | |

| n90 | 52 | – | ||

| MCI | 6 months | n80 | 106 | 1698 |

| n90 | 142 | 2273 | ||

| 12 months | n80 | 79 | 883 | |

| n90 | 106 | 1183 | ||

| 18 months | n80 | 81 | 381 | |

| n90 | 109 | 510 | ||

| 24 months | n80 | 67 | – | |

| n90 | 90 | – |

Uncorrected: Sample size requirements necessary for 80% power (n80) and 90% power (n90) at 6, 12, and 24 months for AD subjects and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months for MCI subjects (data taken from Hua et al. (2010) Table 1 p. 68). Corrected: Sample size requirements for Stat-ROI recalibrated as percent change from 6 months. Note, corrected Stat-ROI at 6 months is computed as Stat-ROI percent change from 0–12 months minus Stat-ROI percent change from 0–6 months, with standard deviation taken from Stat-ROI percent change from 0–12 months; corrected Stat-ROI at 18 months is computed as Stat-ROI percent change from 0–24 months minus Stat-ROI percent change from 0–6months,with standard deviation taken from Stat-ROI percent change from 0–24 months, etc. Dashes indicate time intervals with no data.

Of particular interest is the deceleration of percent decline from baseline subsequent to the first follow-up scan at 6 months (observable in the left panel of Fig. 1), implying that the Stat-ROI atrophies rapidly from baseline to 6 months, but much more slowly thereafter in both AD and MCI subjects. For example, the mean percent change of the Stat-ROI from baseline to 6 months in AD subjects is 2.1%, whereas there is only a 1% decline (=3.1%–2.1%) from 6–12 months, and an additional 0.8% decline (=3.9%–3.1%) from 12–24 months. The effects are similar for MCI subjects: while there is a 1.8% decline from 0–6 months in the Stat-ROI, this decelerates with only an additional 0.5% from 6–12 months, 0.3% from 12–18 months, and 0.5% from 18–24 months. The differences between 0–6 month and subsequent atrophy rates are highly significant; using publicly-available ADNI data downloaded on May 5, 2010 we performed paired t-tests for the rate of change per 6 months for AD subjects (0–6 months vs. 6–12 months: t=5.69, df=80, p<0.0001; 0–6months vs. 12–24 months: t=12.3, df=80, p<0.0001) and for MCI subjects (0–6months vs. 6–12 months: t=9.64, df=197, p<0.0001; 0–6 months vs. 12–18 months: t=12.7, df=197, p<0.0001; 0–6 months vs. 18–24 months: t=11.0, df=197, p<0.0001). We included only those subjects who had completed scans at all scheduled time points, although results change little using the entire available sample. Also, while the sample used in these calculations differs slightly from that of Hua et al., the estimated rates of atrophy are very similar (right panel of Fig. 1).

Thus, more than 50% of the decline in Stat-ROI over a period of 24 months occurs within the first 6 months after baseline in both AD and MCI groups. It is difficult to ascribe this phenomenon (the rapid atrophy of Stat-ROI after study entry followed by a sudden deceleration after 6 months) to the effects of disease processes alone, since ADNI was an observational rather than a treatment study and subject baselines do not have an obvious relationship with rates of atrophy that would apply to either the AD or the MCI groups. To the contrary, other reports have shown that rates of brain atrophy tend to accelerate as disease progresses from preclinical to early AD, e.g., Chan et al. (2003) and McDonald et al. (2009). This suggests the alternative explanation that the within-subject quantification of longitudinal Stat-ROI atrophy is over-estimated due to methodological bias.

To further explore the possibility of methodological bias, we computed the mean rates of Stat-ROI atrophy (percent change from baseline) at 6, 12, and 24 months for a sample of 160 HC subjects (mean age = 76, sd = 5 at baseline), from Stat-ROI measures publicly-available in ADNI’s derived-data collection, downloaded on May 5, 2010. These HC Stat-ROI measures, though not reported on by Hua et al., were produced by the same ADNI researchers using the same longitudinal registration methods as used to calculate the AD and MCIStat-ROI measures that were analyzed in Hua et al. The resulting estimates are illustrated in the right panel of Fig. 1. The Stat-ROI declined 1.7% from baseline to 6 months; from 6–12 months there was an additional 0.2% decline (=1.9% – 1.7%) and from 12–24 months there was a decline of 0.3% (=2.2% – 1.9%). Thus, over 75% of the reported atrophy for HCs occurred within the first 6 months. Using paired t-tests, the differences in rates per 6 months in the HC sample are highly significant (0–6 months vs. 6–12 months: t = 8.0, df = 159, p < 0.0001; 0–6 months vs. 12–24 months: t = 13.4, df = 159, p < 0.0001). Moreover, using two-sample t-tests with unequal variances, the rate of change for HC from baseline to 6 months is significantly higher than the rate of change for both AD and MCI subsequent to 6 months (e.g., HC 0–6 months vs. AD 6–12 months: t = 4.5, df = 140, p < 0.0001; HC 0–6 months vs. MCI 6–12 months: t = 9.0, df = 354, p < 0.0001).

HC subjects thus exhibit a high mean rate of Stat-ROI atrophy from baseline to 6 months, followed by a sharp deceleration of the rate from 6–24 months, a temporal trajectory quite similar to that of the AD and MCI subjects, but even more pronounced. This argues strongly against attributing the estimated Stat-ROI trajectory of atrophy in AD and MCI solely to disease processes. Rather, the alternative given previously – that the trajectory of atrophy may partly reflect systematic bias due to image analysis procedures – a fortiori suggests itself as an entirely more plausible explanation.

Despite efforts to mitigate it (Yanovsky et al., 2009), such a bias could result from differential smoothing due to asymmetry in the interpolation of baseline and follow-up images during longitudinal image registration (Yushkevich et al., 2010). If atrophy, measured with respect to baseline, in longitudinal measures is systematically biased upward because of the method of registration with baseline scans, this would result to a first approximation in the same trajectory of atrophy as that calculated for the AD, MCI, and HC subjects using the Stat-ROIs of Hua et al. (Yushkevich et al., 2010). Because all of a subject’s follow-up images were registered with his or her baseline image, and the resulting volume-change field subsequently mapped to an atlas, any systematic upward bias in estimated rates of atrophy due to asymmetric registration would show up as increased mean rates of atrophy relative to baseline only; mean rates of atrophy recalibrated relative to any post-baseline point (e.g., 6 months in Hua et al.) would subtract out this first-order longitudinal registration bias and hence would provide a more consistent basis for estimating the true mean rate of atrophy.

Thus, to correct for potential bias, we recomputed the effect sizes using differences in mean percent change of Stat-ROIs starting at 6 months (AD: 6–12 months = 1%, 6–24 months = 1.8%; MCI: 6–12 months = 0.5%, 6–18 months = 0.8%, 6–24 months = 1.3%). In Table 1 we present sample size estimates necessary to obtain 80% and 90% power to detect a 25% reduction in Stat-ROI mean rates of atrophy recalibrated as percent change from 6 months. These sample size estimates are between 4.7 and 16 times larger than those reported in Hua et al. Using the Stat-ROI for AD clinical trial outcomes with the uncorrected sample size estimates in Table 1 would therefore result in severely underpowered studies relative to the corrected sample size requirements, likely leading to unreliable and non-significant treatment effect estimates, with potentially serious implications if used for selecting dosage in clinical trials (Cummings, 2010). Note, we used the data summaries from Hua et al. (Fig. 3, p. 68) to make our results as comparable as possible to theirs; effect sizes computed similarly from publicly-available ADNI data current on May 5, 2010 give somewhat larger estimates for sample size requirements.

It should be noted that any potential bias due to registration methodology can be eliminated by making sure the entire procedure is symmetric, by construction. Since the change measured from baseline to 6 months should equal the inverse of the change measured from 6-months to baseline, a simple method for achieving symmetry is to measure the change in both directions independently, and then combining them by algebraic or geometric averaging. Error metrics for (1) inverse consistency of forward and reverse registrations, and (2) transitivity of pair-wise registrations, can also be computed to evaluate the quality of registration algorithms (Klein et al., 2009).

It is also important to compare longitudinal atrophy in AD and MCI groups with that in an HC group, as done by Holland et al. (2009) and Schott et al. (2010). As pointed out by Hua et al. (2009), longitudinal atrophy estimates in an HC group can provide a useful benchmark to evaluate the plausibility of unbiasedness assumptions for the method of longitudinal registration employed, and as a potentially more realistic reference condition for sample and effect size estimates than the “no temporal change” reference condition (Fox et al., 2000).

Acknowledgments

Data collection and sharing for this commentary was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Abbott, AstraZeneca AB, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai Global Clinical Development, Elan Corporation, Genentech, GE Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Innogenetics, Johnson and Johnson, Eli Lilly and Co., Medpace, Inc., Merck and Co., Inc., Novartis AG, Pfizer Inc, F. Hoffman-La Roche, Schering-Plough, Synarc, Inc., as well as non-profit partners the Alzheimer’s Association and Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, with participation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Private sector contributions to ADNI are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (http://www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. This research was also supported by NIH grants P30 AG010129, K01 AG030514, the Dana Foundation, and the ADNI ancillary grant AG031224.

We would also like to thank Anders Dale for his invaluable assistance and expertise.

References

- Ashburner J, Andersson JL, Friston KJ. Image registration using a symmetric prior–in three dimensions. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2000 Apr;9:212–225. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200004)9:4<212::AID-HBM3>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett LA, Harvey DJ, Gamst A, Donohue M, Kornak J, Zhang H, Kuo JH. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: annual change in biomarkers and clinical outcomes. Alzheimers Dement. 2010 May;6:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D, Janssen JC, Whitwell JL, Watt HC, Jenkins R, Frost C, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Change in rates of cerebral atrophy over time in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: longitudinal MRI study. Lancet. 2003 Oct;362:1121–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen GE. Information processing in medical imaging. Ch. Consistent Linear-elastic Transformations for Image Matching. Vol. 1613. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 1999. pp. 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. Integrating ADNI results into Alzheimer’s disease drug development programs. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010 Aug;31:1481–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NC, Cousens S, Scahill R, Harvey RJ, Rossor MN. Using serial registered brain magnetic resonance imaging to measure disease progression in Alzheimer disease: power calculations and estimates of sample size to detect treatment effects. Arch. Neurol. 2000 Mar;57:339–344. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AJ, Hua X, Lee S, Leow AD, Yanovsky I, Gutman B, Dinov ID, Lepore N, Stein JL, Toga AW, Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Reiman EM, Harvey DJ, Kornak J, Schuff N, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Comparing 3T and 1.5T MRI for tracking Alzheimer’s disease progression with tensor-based morphometry. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010 Apr;31:499–514. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland D, Brewer JB, Hagler DJ, Fenema-Notestine C, Dale AM. Subregional neuroanatomical change as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009 Dec;106(49):20954–20959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906053106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Leow A, Lee S, Klunder A, Toga A, Lepore N, Chou Y, Brun C, Chiang M, Barysheva M, Jack C, Jr., Bernstein M, Britson P, Ward C, Whitwell J, Borowski B, Fleisher A, Fox N, Boyes R, Barnes J, Harvey D, Kornak J, Schuff N, Boreta L, Alexander G, Weiner M, Thompson P. 3D characterization of brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using tensor-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2008a May;41:19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Leow AD, Parikshak N, Lee S, Chiang MC, Toga AW, Jack CR, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Tensor-based morphometry as a neuroimaging biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: an MRI study of 676 AD, MCI, and normal subjects. Neuroimage. 2008b Nov;43:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Lee S, Yanovsky I, Leow AD, Chou YY, Ho AJ, Gutman B, Toga AW, Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Reiman EM, Harvey DJ, Kornak J, Schuff N, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Optimizing power to track brain degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment with tensor-based morphometry: an ADNI study of 515 subjects. Neuroimage. 2009 Dec;48:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Lee S, Hibar DP, Yanovsky I, Leow AD, Toga AW, Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Reiman EM, Harvey DJ, Kornak J, Schuff N, Alexander GE, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Mapping Alzheimer’s disease progression in 1309 MRI scans: power estimates for different inter-scan intervals. Neuroimage. 2010 May;51:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Borowski BJ, Gunter JL, Fox NC, Thompson PM, Schuff N, Krueger G, Killiany RJ, Decarli CS, Dale AM, Carmichael OW, Tosun D, Weiner MW. Update on the magnetic resonance imaging core of the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2010 May;6:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Andersson J, Ardekani BA, Ashburner J, Avants B, Chiang MC, Christensen GE, Collins DL, Gee J, Hellier P, Song JH, Jenkinson M, Lepage C, Rueckert D, Thompson P, Vercauteren T, Woods RP, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Evaluation of 14 nonlinear deformation algorithms applied to human brain MRI registration. Neuroimage. 2009 Jul;46:786–802. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohannim O, Hua X, Hibar DP, Lee S, Chou YY, Toga AW, Jack CR, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. Boosting power for clinical trials using classifiers based on multiple biomarkers. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010 Aug;31:1429–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leow AD, Yanovsky I, Chiang MC, Lee AD, Klunder AD, Lu A, Becker JT, Davis SW, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Statistical properties of Jacobian maps and the realization of unbiased large-deformation nonlinear image registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2007 Jun;26:822–832. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.892646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CR, McEvoy LK, Gharapetian L, Fennema-Notestine C, Hagler DJ, Holland D, Koyama A, Brewer JB, Dale AM. Regional rates of neocortical atrophy from normal aging to early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009 Aug;73:457–465. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b16431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott JM, Bartlett JW, Barnes J, Leung KK, Ourselin S, Fox N. Reduced sample sizes for atrophy outcomes in Alzheimer’s disease trials: baseline adjustment. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010 Aug;31:1452–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovsky I, Leow AD, Lee S, Osher SJ, Thompson PM. Comparing registration methods for mapping brain change using tensor-based morphometry. Med. Image Anal. 2009 Oct;13:679–700. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yushkevich PA, Avants BB, Das SR, Pluta J, Altinay M, Craige C. Bias in estimation of hippocampal atrophy using deformation-based morphometry arises from asymmetric global normalization: an illustration in ADNI 3 T MRI data. Neuroimage. 2010 Apr;50:434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]