SUMMARY

Tumor maintenance relies on continued activity of driver oncogenes, although their rate-limiting role is highly context dependent. Oncogenic Kras mutation is the signature event in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), serving a critical role in tumor initiation. Here, an inducible KrasG12D-driven PDAC mouse model establishes that advanced PDAC remains strictly dependent on KrasG12D expression. Transcriptome and metabolomic analyses indicate that KrasG12D serves a vital role in controlling tumor metabolism through stimulation of glucose uptake and channeling of glucose intermediates into the hexosamine biosynthesis and pentose phosphate pathways (PPP). These studies also reveal that oncogenic Kras promotes ribose biogenesis. Unlike canonical models, we demonstrate that KrasG12D drives glycolysis intermediates into the nonoxidative PPP, thereby decoupling ribose biogenesis from NADP/NADPH-mediated redox control. Together, this work provides in vivo mechanistic insights into how oncogenic Kras promotes metabolic reprogramming in native tumors and illuminates potential metabolic targets that can be exploited for therapeutic benefit in PDAC.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is among the most lethal cancers with a 5-year survival rate of ~5% (Hidalgo, 2010). Malignant progression from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanINs) to invasive and metastatic disease is accompanied by the early acquisition of activating mutations in the KRAS oncogene, which occurs in >90% of cases, and subsequent loss of tumor suppressors including INK4A/ARF, TP53, and SMAD4 (Hezel et al., 2006). Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMM) have provided evidence for oncogenic Kras (KrasG12D) as a major driver in PDAC initiation, with the aforementioned tumor suppressor genes constraining progression (Aguirre et al., 2003; Guerra et al., 2003; Hingorani et al., 2003). Although shRNA extinction of Kras expression as well as pharmacological inhibition of its effectors can impair growth of human PDAC lines, clinical trials of drugs targeting key components of the RAS-MAPK pathway have shown meager responses (Rinehart et al., 2004; Singh and Settleman, 2009). The paucity of clinical progress may relate to a number of factors including the lack of a tumor maintenance role for oncogenic Kras, redundancy in downstream signaling surrogates, suboptimal penetration of the drug into the tumor, and/or tumor plasticity owing to a myriad of genomic alterations and intratumoral heterogeneity (Hidalgo, 2010).

Constitutive KrasG12D signaling drives uncontrolled proliferation and enhances survival of cancer cells through the activation of its downstream signaling pathways, such as the MAPK and PI3K-mTOR pathways (Gysin et al., 2011). To meet the increased anabolic needs of enhanced proliferation, cancer cells require both sufficient energy and biosynthetic precursors as cellular building blocks to fuel cell growth. In cancer cells, metabolic pathways are rewired in order to divert nutrients, such as glucose and glutamine, into anabolic pathways to satisfy the demand for cellular building blocks (Vander Heiden et al., 2009). Accumulating evidence indicates that the reprogramming of tumor metabolism is under the control of various oncogenic signals (Levine and Puzio-Kuter, 2010). The Ras oncogene in particular has been shown to promote glycolysis (Racker et al., 1985; Yun et al., 2009). However, the mechanisms by which oncogenic Kras coordinates the shift in metabolism to sustain tumor growth, particularly in the tumor microenvironment, and whether specific metabolic pathways are essential for Kras-mediated tumor maintenance remain areas of active investigation. Here, we generated an inducible oncogenic Kras model of PDAC and establish that this gene is essential for tumor maintenance in vivo. Integrated transcriptomic, biochemical, and metabolomic analyses reveal a fundamental role of the Kras oncogene in reprogramming tumor metabolism by selectively activating biosynthetic pathways to maintain tumor growth.

RESULTS

KrasG12D Is Essential for PDAC Maintenance

To control KrasG12D expression in a temporal- and tissue-specific manner, we generated a conditional KrasG12D transgene under the control of a tet-operator with a lox-stop-lox (LSL) cassette inserted between the promoter and the start codon of the KrasG12D open reading frame (tetO_Lox-Stop-Lox-KrasG12D, designated tetO_LKrasG12D) (Figure S1A available online). These mice were crossed to ROSA26-LSL-rtTA-IRES-GFP (ROSA_rtTA) (Belteki et al., 2005) and p48-Cre (Kawaguchi et al., 2002) mice to enable pancreas-specific and doxycycline (doxy)-inducible expression of KrasG12D (Figure S1B). This triple transgenic strain is designated hereafter as iKras. Doxy treatment effectively induced oncogenic Kras expression and activity (Figures S1C and S1D), but did not substantially increase total Kras expression at the mRNA or protein levels (Figures S1C and S1E). Extinction of the KrasG12D transgene occurs within 24 hr following doxy withdrawal (Figures S1C and S1D).

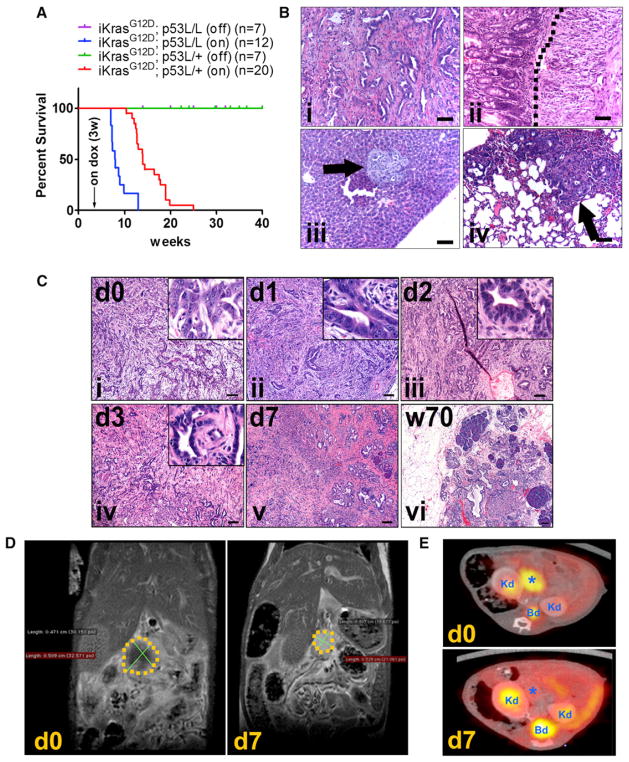

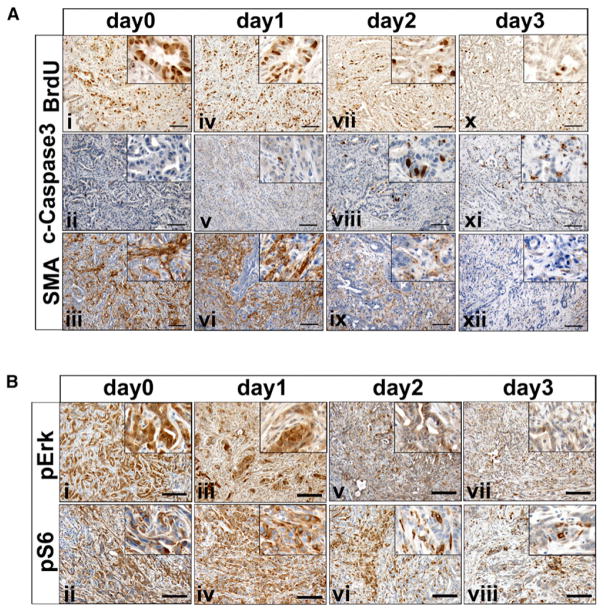

Consistent with the role of KrasG12D as a driver of PDAC initiation (Hezel et al., 2006), doxy induction provokes acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and PanIN lesions within 2 weeks (Figure S1F). Similar to the LSL-KrasG12D knock-in model, induction of the KrasG12D transgene leads to infrequent occurrence of invasive PDAC after long latency (35–70 weeks) (Figure S1F), suggesting comparable biological activity of the KrasG12D alleles and the need for additional genetic events for tumor progression. To enable full malignant progression and assess the tumor maintenance role of KrasG12D in advanced malignancies, we crossed iKras and conditional p53 knockout (p53L) alleles (Marino et al., 2000). Following doxy treatment at 3 weeks of age, all iKras p53L/+ mice succumbed to PDAC between 11 and 25 weeks of age (median survival, 15 weeks), whereas the doxy-treated iKras p53L/L mice succumbed to PDAC more rapidly with a median survival of 7.9 weeks (Figure 1A). The iKras p53 mutant tumors exhibited features commonly found in human PDAC, including glandular tumor structures, exuberant stroma, local invasion into surrounding structures such as the duodenum, and distant metastases to the liver and lung (Figure 1B). Histological analysis documented invasive PDAC in 8/8 iKras p53L/+ mice at 8 weeks after induction (Figure S1G). As such, we assessed the impact of KrasG12D extinction on tumor biology and maintenance at 9 weeks after induction. As shown in Figure 1C, KrasG12D extinction led to rapid tumor regression with morphological deterioration of tumor cells and rapid degeneration of stromal elements starting 48 hr and peaking at 72 hr following doxy withdrawal. After 1 week of doxy withdrawal, MRI showed a reduction in tumor mass of ~50%, whereas PET/CT showed complete loss of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake (Figures 1D and 1E). On the histopathological level, virtually all malignant components of the tumor regressed with the remaining pancreata displaying collagen deposition surrounding few remnant ductal structures (Figure 1C). Correspondingly, tumor regression was accompanied by decreased tumor cell proliferation (BrdU incorporation) and increased apoptosis (Caspase-3 activation) 2–3 days after doxy withdrawal, culminating in complete loss of tumor cell proliferation at 1 week off doxy (Figures 2A and S2A; data not shown). Moreover, KrasG12D extinction effected dramatic changes in the tumor stroma as evidenced by a reduction in pancreatic stellate cells (marked by SMA staining) (Figure 2A), which is a prominent component of the classical stromal reaction in PDAC. This indicates that oncogenic Kras has significant non-cell-autonomous effects on the stromal compartment. The in vivo findings of decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of the epithelial compartment parallel cell culture assays, such as loss of clonogenic growth of primary tumor cells (Figure S2B), consistent with a role for cell-autonomous mechanisms contributing to tumor regression. Together, these findings establish that KrasG12D expression is required for PDAC maintenance in this autochthonous model, supporting both the proliferation and viability of tumor cells and its associated stroma.

Figure 1. KrasG12D Inactivation Leads to Rapid Tumor Regression.

(A) Kaplan-Meier overall survival analysis for mice of indicated genotypes. Cohort size for each genotype is indicated. Arrow: time point for starting doxy treatment. On: mice were fed with doxy-containing water from 3 weeks of age. Off: mice were maintained doxy-free.

(B) Histopathological characterization of PDAC from iKras p53L/+ mice showing (i) typical ductal adenocarcinoma with well-differentiated glandular tumor cells and strong stromal reaction; (ii) local invasion of tumor cells (right of the dotted line) into duodenum wall; (iii) liver metastasis (arrow); and (iv) lung metastasis (arrow).

(C) H&E staining shows histological changes of PDAC at the indicated time points after doxy withdrawal. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

(D) MRI scan illustrating tumor (area within the dotted line) shrinkage following 7 days of doxy withdrawal.

(E) 18FDG-PET/CT scan of tumor bearing mice at day 0 and day 7 upon doxy withdrawal. *, tumor; Kd, kidney; Bd, bladder dome.

See also Figure S1.

Figure 2. Histopathological Characterization of Tumor Regression upon KrasG12D Inactivation.

(A) iKras p53L/+ mice were fed with doxy-containing water for 9 weeks from 3 weeks of age. The mice were pulled from doxy treatment at the indicated days and injected with BrdU. Pancreatic tumors were stained with antibodies to BrdU (panels i, iv, vii, x), cleaved-caspase3 (panels ii, v, viii, xi), and SMA (panels iii, vi, ix, xii).

(B) Pancreatic tumors from (A) were stained with antibodies to phospho-Erk (panels i, iii, v, vii) and phospho-S6 (panels ii, iv, vi, viii). Scale bar represents 100 mm.

See also Figure S2.

These biological changes aligned with changes in prototypical Kras signaling components, including a decrease in MAPK signaling measured by phospho-Erk as early as 24 hr following doxy withdrawal (Figure 2B), preceding any obvious changes in tumor morphology. Decreased phospho-Erk was followed by dampened mTOR signaling, as evidenced by a decreased phospho-S6 in tumor cells, although the signal remained high in some stromal cells (Figure 2B). These in vivo signaling patterns matched those seen in cultured tumor cells (Figure S2C). As expected, LSL-KrasG12D p53L/+ primary tumor cell cultures showed no doxy-dependent signaling changes (Figure S2D).

KrasG12D Regulates Multiple Metabolic Pathways at the Transcriptional Level

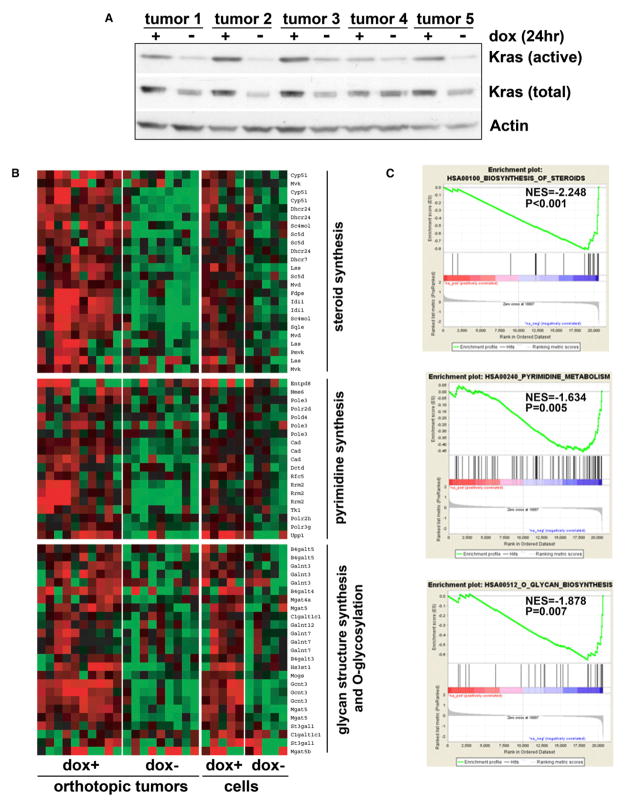

To gain further mechanistic insight into KrasG12D-mediated tumor maintenance, transcriptomic analysis was conducted using orthotopic iKras p53 null tumors generated from five independent primary tumor lines. Importantly, these orthotopic tumors faithfully recapitulated histological and molecular features of the primary tumors (Figure S3A). To audit proximal molecular changes linked to KrasG12D extinction, tumors were harvested at 24 hr following doxy withdrawal. This time point shows documented loss of Ras activity (Figure 3A), yet absence of morphological changes or a significant decrease in proliferation (Figure S2A). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian et al., 2005) of the in vivo and in vitro KrasG12D transcriptome using the KEGG gene sets showed striking representation of metabolic processes, including the downregulation of steroid biosynthesis, pyrimidine metabolism, O-glycan biosynthesis, and glycan structures biosynthesis pathways (Figures 3B and 3C and Table S1). Moreover, xenograft tumors and cultured parental lines exhibited significant correlation in expression levels for the differentially expressed genes (Figure S3B), suggesting that the cultured tumor cell lines may serve to complement tumor studies in vivo.

Figure 3. Transcriptional Changes Induced by KrasG12D Inactivation.

(A) Orthotopic xenograft tumors were generated from five independent primary iKras p53L/+ PDAC cell lines. Animals were kept on doxy for 2 weeks until tumors were fully established. Half of the animals were pulled off doxy for 24 hr at which point tumor lysate was prepared. Ras activity was measured with Raf-RBD pull-down assay.

(B) Heat maps of the genes enriched in indicated metabolism pathways illustrate the changes in gene expression upon doxy withdrawal. Expression levels shown are representative of log2 values of each replicate from either xenograft tumors or cultured parental cell lines. Red signal denotes higher expression relative to the mean expression level within the group and green signal denotes lower expression relative to the mean expression level within the group.

(C) GSEA plot of steroid biosynthesis (top), pyrimidine metabolism (middle), and O-glycan biosynthesis (bottom) pathways based on the off-doxy versus on-doxy gene expression profiles. NES denotes normalized enrichment score.

See also Figure S3.

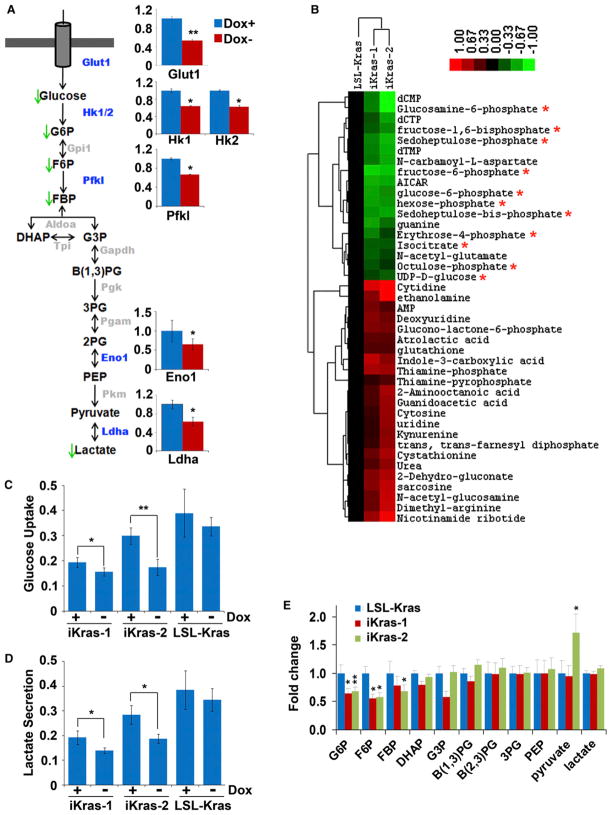

KrasG12D Enhances Glycolytic Flux

To interrogate the role of KrasG12D in the regulation of tumor metabolism, targeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) metabolomic studies were performed to comprehensively characterize metabolic alterations immediately following KrasG12D withdrawal (Yuan et al., 2012). This analysis revealed that KrasG12D extinction effected significant metabolic changes involving multiple pathways, the most significant of which are intermediates in glucose metabolism (Figures 4A and 4B). Consistent with the function of KrasG12D in the regulation of glycolysis (Racker et al., 1985), KrasG12D extinction was accompanied by a significant drop in glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), fructose-6-phosphate (F6P), and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) with minimal changes to the remaining components in glycolysis (Figure 4E). In addition, KrasG12D extinction led to decreased glucose uptake and lactate production (Figures 4C and 4D), demonstrating that oncogenic KrasG12D enhances glycolytic flux in PDAC. These metabolic changes were highly concordant with the gene expression changes from the transcriptional profiles, which showed downregulation of the glucose transporter (Glut1/Slc2a1) and several other rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes Hk1, Hk2, and Pfkl, as well as Ldha, the enzyme responsible for converting pyruvate to lactate (Figures 4A and S4A). These data suggest that KrasG12D is essential for glucose utilization in this model through the regulation of multiple rate-limiting steps including those that govern glucose uptake and subsequent metabolism. Interestingly, we also observed that KrasG12D inactivation was not accompanied by significant alterations to TCA cycle intermediates (Figure S4B). This finding is in line with a model whereby proliferating cells divert glucose metabolites into anabolic processes (e.g., nucleotide and lipid biosynthesis) whereas alternative carbon sources are utilized to fuel the TCA cycle (Vander Heiden et al., 2009). Indeed, consistent with previous reports (Gao et al., 2009; Wise et al., 2008), glutamine is the major carbon source for the TCA cycle in the KrasG12D-driven PDAC cells as shown by uniformly labeled (U-13C6)-glucose and U-13C5-glutamine tracing (Figure S4C).

Figure 4. KrasG12D Extinction Leads to Decreased Glucose Uptake and Glycolysis.

(A) Summary of the changes in glycolysis upon KrasG12D inactivation. Metabolites that decrease upon doxy withdrawal are indicated with green arrows. Bar graphs indicate the relative expression levels of differentially expressed glycolytic enzymes that showed a significant decrease in the absence of doxy; the gene names for those enzymes that exhibited significant changes are also highlighted in the cartoon in blue. Glycolytic enzymes whose change in expression was not significant are illustrated in gray.

(B) Heat map of those metabolites that are significantly and consistently changed upon doxy withdrawal between the two iKras p53L/+ lines as determined by targeted LC-MS/MS using SRM. Cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr, at which point metabolite levels were measured from triplicates for each treatment condition. The averaged ratios of off-doxy over on-doxy levels for differentially regulated metabolites are represented in the heat map. Asterisks indicate metabolites involved in glucose metabolism that decrease upon doxy withdrawal.

(C and D) iKras p53L/+ cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr. Relative changes of glucose (C) or lactate (D) levels in the medium were measured and normalized to cell numbers.

(E) Fold changes of glycolytic intermediates upon doxy withdrawal for 24 hr. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Error bars represent SD of the mean. B(1,3)PG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; B(2,3)PG, 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate.

See also Figure S4.

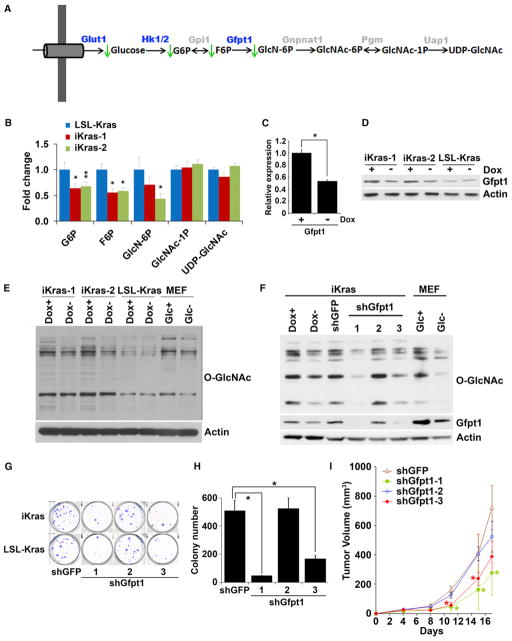

KrasG12D Activates the Hexosamine Biosynthesis Pathway and Protein Glycosylation

Because KrasG12D-regulated glucose metabolites, including G6P and F6P, are precursors for other glucose-utilizing pathways, namely the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), we audited these pathways immediately following KrasG12D inactivation. Steady-state metabolite profiling showed a significant decrease in glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN-6P), the product of the committed step governing entry into HBP (Figures 5A and 5B). Correspondingly, downregulation of the rate-limiting enzyme, Gfpt1, was documented at the transcriptional and protein levels (Figures 5C and 5D). Moreover, the GSEA showed downregulation of O-glycosylation and glycan structure biosynthesis pathways (Figures 3B and S5A) and western blotting of cells off doxy showed a decrease in the levels of total O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) posttranslational modification (Figure 5E), data supported by the fact that the HBP provides the substrate for O- and N-linked glycosylation. This profile of reduced glycosylation is comparable to that observed upon glucose starvation (Figure 5E) and strongly indicates that oncogenic KrasG12D is essential for the maintenance of protein glycosylation in established tumors.

Figure 5. KrasG12D Inactivation Leads to Inhibition of the Hexosamine Biosynthesis Pathway and Protein O-Glycosylation.

(A) Summary of changes in the HBP upon KrasG12D inactivation. Metabolites that decrease upon doxy withdrawal are indicated with green arrows. Differentially expressed genes upon doxy withdrawal are highlighted in blue.

(B) Fold change of metabolites in the HBP upon doxy withdrawal for 24 hr.

(C and D) Relative mRNA (C) and protein levels (D) of Gfpt1 in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr.

(E) Western blot analysis for O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) levels in cells maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr. For control samples, MEFs were cultured in the presence or absence of glucose for 24 hr.

(F) Western blot analysis for O-GlcNAc and Gfpt1 levels in cells infected with shRNA against GFP or Gfpt1.

(G and H) Clonogenic assay (G) and soft-agar colony formation assay (H) for iKras p53L/+ or LSL-Kras p53L/+ PDAC cells infected with shRNA against GFP or Gfpt1.

(I) iKras p53L/+ cell lines were infected with shRNA against GFP or Gfpt1 and subcutaneously injected into nude mice. Tumor volumes were measured and data shown are representative of results from three independent cell lines. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Error bars represent SD of the mean. GlcNAc-1P, N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate; GlcNAc-6P, N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate; GlcN6P, glucosamine 6-phosphate; UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. See also Figure S5.

To further substantiate the essentiality of KrasG12D-mediated control of protein glycosylation, we assessed the impact of shRNA knockdown of Gfpt1. Consistent with its pivotal role in providing protein glycosylation substrates, Gfpt1 knockdown reduced the overall O-linked glycosylation to a level similar to that of tumor cells in which KrasG12D is extinguished (Figure 5F). Gfpt1 knockdown also inhibited the clonogenic and soft-agar growth of tumor cells from both the iKras p53L/+ and the LSL-KrasG12D p53L/+ tumor cells (Figures 5G and 5H) and suppressed xenograft tumor growth in vivo (Figure 5I). Notably, tumors that emerged in the Gfpt1 knockdown group showed recovery of Gfpt1 expression (Figure S5B). Thus, KrasG12D-mediated tumor maintenance is at least partially dependent upon its stimulation of the HBP and associated protein glycosylation.

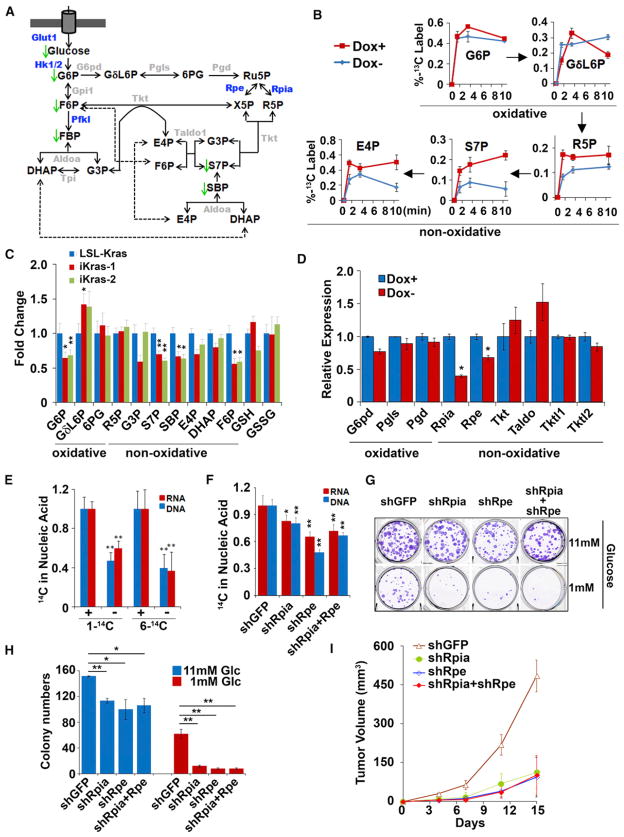

KrasG12D Promotes Ribose Biogenesis through the Nonoxidative Arm of the PPP

The PPP utilizes glucose to generate the ribose ring of DNA/RNA and to maintain cellular reducing power in the form of NADPH (Deberardinis et al., 2008b). Metabolomic profiling also revealed significant changes in several metabolites from the PPP (Figure 6A). In particular, an intermediate unique to the PPP, sedohe-pulose-7-phosphate (S7P), was significantly reduced upon KrasG12D extinction (Figure 6C). To further elucidate the effect of KrasG12D activity on glucose catabolism through the PPP, we used U-13C6-glucose to trace glucose flux into the PPP. Consistent with the steady-state data, we observed that KrasG12D enhanced glycolytic flux without affecting the flux of glycolytic metabolites into the TCA cycle (Figure S6A and data not shown). Moreover, we observed a dramatic reduction in flux of U-13C6-glucose into ribose-5-phosphate (R5P), S7P, and erythose-4-phosphate (E4P), components that are unique to the nonoxidative arm of the PPP (Figure 6B). This was especially striking given that we did not observe changes in flux through the oxidative arm of the PPP (Figure 6B), nor were significant changes evident by steady-state profiling (Figure 6C). Given the link between oncogenic Kras signaling and the non-oxidative arm of the PPP, we sought to compare and quantify flux through the two arms (oxidative and nonoxidative) of the PPP.

Figure 6. KrasG12D Preferentially Enhances Nonoxidative PPP to Support Ribose Biogenesis.

(A) Summary of changes in the PPP upon KrasG12D inactivation. Metabolites that decrease upon doxy withdrawal are indicated with green arrows. Differentially expressed genes upon doxy withdrawal are highlighted in blue.

(B) iKras p53L/+ cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr, at which point U-13C glucose labeling kinetics for the indicated metabolites were compared at 1, 3, and 10 min.

(C) Fold changes for metabolites in the PPP upon doxy withdrawal for 24 hr.

(D) Relative mRNA levels of PPP genes in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr.

(E) iKras p53L/+ cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr, followed by a 24 hr labeling with 1-14C or 6-14C glucose. Incorporation of radioactivity into DNA or RNA were determined and normalized to DNA or RNA concentration.

(F) iKras p53L/+ cells were infected with shRNA against Rpia and Rpe individually or in combination. shRNA against GFP was used as a control. Cells were labeled with 1-14C glucose and incorporation of radioactivity into DNA and RNA was determined as in (E).

(G) iKras p53L/+ cells were maintained under high (11 mM) or low (1 mM) glucose, and clonogenic activity was determined for cells infected with shRNA against GFP, Rpia, or Rpe.

(H) Quantification of colony numbers.

(I) iKras p53L/+ cells were infected with shRNA against GFP, Rpia, or Rpe and subcutaneously injected into nude mice. Tumor volumes were measured and data shown are representative of results from three independent cell lines.

Error bars represent SD of the mean. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; GδL6P, 6-phosphoglucono-δ-lactone; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; 6PG, 6-phosphogluconate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose 5-phosphate; SBP, sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate; X5P, xylulose 5-phosphate. See also Figure S6.

It has been suggested that the oxidative and nonoxidative arms of the PPP can be decoupled to facilitate ribose biosynthesis without affecting the cellular redox balance (NADP+/NADPH ratio) (Boros et al., 1998). To explore this possibility in the context of KrasG12D-driven PDAC, 14C1- or 14C6-labeled glucose was used to measure the production of CO2 from the oxidative PPP (14C1-CO2) relative to that generated from the glycolysis-TCA cycle route (14C6-CO2). Consistent with our previous data showing that KrasG12D deinduction exerts a minimal effect on TCA cycle intermediates (Figure S4B), no obvious change in the release of 14C6-CO2 was observed upon doxy withdrawal (Figure S6B). More importantly, no significant decrease in the release of 14C1-CO2 was detected (Figure S6B), indicating that KrasG12D extinction was not associated with decreased flux through the oxidative arm of the PPP. In addition, cellular reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) levels, which are regulated by NADPH, were not significantly altered by KrasG12D inactivation, as measured by both metabolomic profiling and biochemical analysis (Figures 6C and S6C). These results provide strong evidence that KrasG12D does not mediate the oxidative arm of the PPP.

To further interrogate the differential abundance of nonoxidative PPP metabolites in an oncogenic Kras-dependent manner, we traced the incorporation of individual glucose carbons using 1,2-labeled 13C-glucose. As shown in Figure S6D, KrasG12D extinction leads to a significant decrease in 1,2-13C-labeled G3P and F6P (glycolytic and PPP metabolites) and the nonoxidative PPP-specific metabolites S7P and sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate (SBP). Consistent with the 1,2-labeling experiment, we also observed a significant decrease of SBP upon KrasG12D inactivation in the steady-state analysis (Figure 6C). SBP was recently shown to be a metabolite in the nonoxidative PPP, whose hydrolysis to S7P provides the thermodynamic driving force to propel ribose biogenesis without engaging the oxidative arm (Clasquin et al., 2011). The downregulation of SBP upon oncogene extinction implies that KrasG12D may utilize this mechanism to facilitate flux through the nonoxidative arm of the PPP, although the enzyme responsible for mediating this reaction in mammals remains to be discovered.

A primary role of the nonoxidative arm of the PPP is to generate ribose-5-phosphate (R5P). As such, we hypothesized that the flux of glucose into the nonoxidative arm of the PPP by KrasG12D occurs to provide tumor cells with sufficient R5P for DNA/RNA biosynthesis. To explore this possibility, we used 14C1- or 14C6-labeled glucose to track the contribution of oxidative versus nonoxidative PPP into DNA and RNA. Whereas 14 C6-labeled glucose will give rise to radioactive DNA/RNA whether it is used by the oxidative or the nonoxidative arm of the PPP, 14C1-labeled glucose will only give rise to radioactive DNA/RNA if it is used by the nonoxidative arm (the 14C1 label is lost as CO2 through the oxidative arm; Figure S6B). As shown in Figure 6E, KrasG12D extinction leads to dramatic drop in the incorporation of both 14C1- and 14C6-labeled glucose into DNA/RNA, clearly demonstrating a predominant and KrasG12D-mediated role for the nonoxidative arm of the PPP in R5P-biogenesis. These data reveal an important role for KrasG12D in preferential maintenance of glycolytic flux through the nonoxidative arm of the PPP in PDAC tumors.

Inhibition of the Nonoxidative PPP Suppresses KrasG12D-Dependent Tumorigenesis

In agreement with the specific regulation of the nonoxidative arm of the PPP, the enzymes involved in the oxidative arm, including G6pd, Pgls, and Pgd, as well as the enzymatic activity of G6pd (the rate-limiting step for the oxidative arm) were not altered upon KrasG12D extinction (Figures 6D and S6E). In contrast, the expression levels of Rpia and Rpe, enzymes that regulate carbon exchange reactions in the nonoxidative arm of the PPP, were significantly decreased (Figure 6D). In agreement with their roles in the nonoxidative PPP, knockdown of either Rpia or Rpe, or the combination, significantly reduced the flux of 14C1-labeled glucose into DNA/RNA (Figures 6F and S6F), indicating that the selective regulation of nonoxidative PPP flux by oncogenic Kras is, at least, partially mediated through Rpia and Rpe. More importantly, although Rpia or Rpe knockdown moderately suppresses the clonogenic activity of iKras p53L/+ tumor cells in high-glucose (11 mM), the inhibitory effect is dramatically enhanced when cells were switched to low-glucose containing media (1 mM) (Figures 6G and 6H), a condition that may reflect the decreased glucose uptake and glycolytic flux after KrasG12D extinction. These findings were corroborated with the decrease in xenograft tumor growth upon Rpia or Rpe knockdown (Figure 6I), further supporting the functional importance of the non-oxidative PPP during KrasG12D-mediated PDAC maintenance.

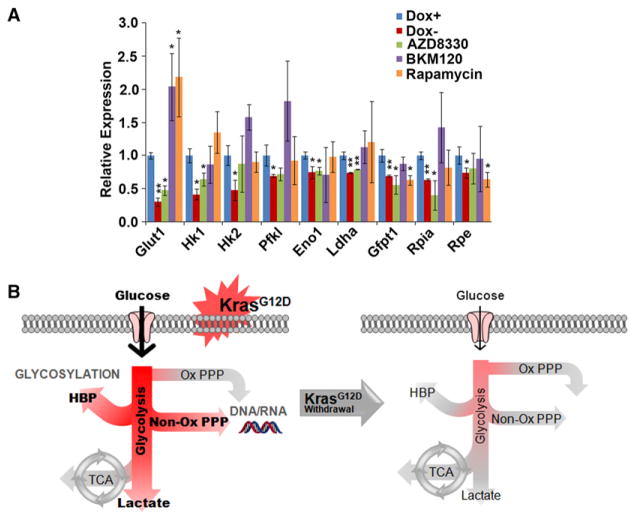

KrasG12D Reprograms Metabolism in PDAC through MAPK and Myc Pathways

To further dissect the downstream mechanism of KrasG12D-mediated metabolic reprogramming, we used specific pharmacological inhibitors to examine the impact of effector pathways on tumor metabolism. As shown in Figure 7A, the expression of several glycolytic genes (Glut1, Hk1, Eno1, Ldha), the rate-limiting HBP gene (Gfpt1), as well as a nonoxidative PPP gene (Rpia) are significantly decreased by MEK inhibition (AZD8330) at a dose that exerts a similar effect on ERK phosphorylation as that observed upon doxy withdrawal (Figure S7A). Consistently, MAPK inhibition recapitulated the KrasG12D inactivation-induced metabolite changes in the glycolysis, HBP and nonoxidative PPP pathways (Figure S7B). These data indicate that the MAPK pathway is a major effector of oncogenic Kras-mediated glucose metabolism remodeling in PDAC, which is consistent with the rapid decrease of MAPK signaling upon oncogene inactivation (Figures 2B, S2C, and S2D). In contrast, although mTOR signaling is also suppressed upon KrasG12D inactivation, Rapamycin treatment did not induce extensive changes in glucose metabolism. In agreement with the minimal alteration in Akt signaling upon oncogene silencing (Figures S2C and S2D), inhibition of PI3K-AKT signaling (BKM120) did not exhibit a significant impact on iKras-directed tumor metabolism (Figures 7A, S7A, and S7B).

Figure 7. MAPK Pathway Is Critical for KrasG12D-Mediated Metabolism Reprogramming.

(A) iKras p53L/+ cells were treated with AZD8330 (50 nM), BKM120 (150 nM), or Rapamycin (20 nM) for 18 hr. In parallel, cells were cultured in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr to serve as controls and relative mRNA levels of indicated metabolism genes were measured by QPCR. Error bars represent SD of the mean. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

(B) Schematic representation of the shift in glucose metabolism upon KrasG12D withdrawal. Activation of oncogenic Kras enables PDAC tumor maintenance through the increased uptake of glucose and subsequent shunting into glycolysis, the HBP pathway (to enable enhanced glycosylation) and the nonoxidative arm of the PPP (to facilitate ribose biosynthesis for DNA/RNA). Glucose flux into the oxidative arm of the PPP and the TCA cycle do not change when KrasG12D is inactivated.

To gain further insight into the KrasG12D-mediated transcriptional regulation that facilitates metabolic reprogramming, promoter analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes upon KrasG12D inactivation. In silico cis-element analysis revealed a highly significant enrichment of the Myc binding element (Figure S7C, p = 5.11 × 10−65). Furthermore, Myc protein level was decreased upon KrasG12D inactivation or MEK inhibitor treatment (Figures S7A and S7D). Because it has been shown that Myc is required for Ras-dependent tumor maintenance (Soucek et al., 2008), we hypothesized that Myc may be a prominent mediator of the KrasG12D-dependent transcriptional regulation of metabolism genes. Indeed, shRNA knockdown of Myc in iKras PDAC cells significantly downregulated the expression of metabolism genes in the glycolysis, HBP, and nonoxidative PPP pathways (Figures S7E and S7F). Another possible candidate mediator of Kras-induced transcriptional changes of metabolism genes was HIF1α. Although there was some enrichment of HIF1α promoter elements in the Kras transcriptional changes, knockdown of HIF1α had only minimal impact on metabolic enzyme expression (data not shown). Together, our data indicates that the MAPK pathway and Myc-directed transcriptional control play key roles for KrasG12D-mediated metabolic reprogramming in PDAC.

DISCUSSION

In this study, an inducible KrasG12D-driven PDAC model provided genetic evidence that oncogenic Kras serves a tumor maintenance role in fully established PDAC. Integrated genomic, biochemical, and metabolomic analyses immediately following KrasG12D extinction revealed a prominent perturbation of multiple metabolic pathways. In particular, KrasG12D exerts potent control of glycolysis through regulation of glucose transporter and several rate-limiting enzymes at the transcriptional level, which collectively serve to shunt glucose metabolism toward anabolic pathways, such as HBP for protein glycosylation and PPP for ribose production (Figure 7B). Notably, we identified an unexpected connection between oncogenic Kras and the nonoxidative arm of the PPP, which functions to provide precursors for DNA and RNA biosynthesis. The functional validation of several KrasG12D-regulated metabolic enzymes provide candidate therapeutic targets and associated biomarkers for the signature oncogene in this intractable disease.

KrasG12D Is Required for PDAC Maintenance

Studies in multiple GEMMs have shown that tumor maintenance is often dependent on the driver oncogene that initiates tumor development (Chin et al., 1999; Felsher and Bishop, 1999; Fisher et al., 2001; Moody et al., 2002). However, recent in vitro studies in human PDAC cell lines have indicated that certain pancreatic cell lines expressing mutant Kras may lose dependence on this oncogene (Singh et al., 2009), raising the question whether oncogenic Kras remains relevant to tumor maintenance in advanced PDAC in the in vivo setting. In our study, the observation of a complete regression of fully established tumors ~1 week upon KrasG12D extinction underscores the essential role of this signature oncogene in PDAC, although we cannot exclude the possibility that residual cancer cells may remain. Additionally, our data uncovers a key relationship between the oncogenic Kras-expressing tumor cells and the prominent desmoplastic stroma that is characteristic of PDAC. Upon Kras extinction, there is a rapid reduction in SMA-positive pancreatic stellate cells. Recent work has shown a correlation between stromal SMA positivity and poor prognosis in PDAC patients (Fujita et al., 2010). It is tempting to speculate that KrasG12D may promote the paracrine secretion of prostromal factors such as Sonic Hedgehog (Neesse et al., 2011); however, further work will be necessary to define this complex relationship.

Oncogenic KrasG12D Directs Glucose Metabolism into Biosynthetic Pathways in PDAC

The reprogramming of cellular metabolism to support continuous proliferation is a hallmark of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Our analysis in vivo following KrasG12D extinction showed rapid downregulation of specific metabolic enzymes and their pathways prior to any discernible biological impact (e.g., morphological or proliferative changes), a finding consistent with the active control of tumor cell metabolism by KrasG12D. Indeed, the Kras oncogene is known to induce aerobic glycolysis (Racker et al., 1985), and PDAC cells have been shown previously to have metabolism consistent with elevated aerobic glycolysis (Zhou et al., 2011). Interestingly, this metabolic switch may be dependent on cell type or oncogenic Ras isoform as H-Ras transformed mesenchymal stem cells do not depend on increased glycolysis for ATP production during transformation (Funes et al., 2007).

The striking and specific transcriptional alteration of metabolic gene expression, which shows high concordance with the actual changes in metabolism, adds to the well-established means of metabolic regulation by allosteric effects on rate-limiting enzymes. Our findings underscore the relevance of gene expression as a mechanism to achieve metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells to determine the metabolic flux route and rate (DeBerardinis et al., 2008a). Another important feature of such transcriptional regulation is that the rewiring of metabolism pathways by the Kras oncogene is achieved through the highly coordinated control over multiple nodes, including rate-limiting enzymes.

Our work establishes that KrasG12D extinction leads to inhibition of glucose uptake and a decrease in several glycolytic intermediates, including G6P, F6P, and FBP. Although aerobic glycolysis is recognized as inefficient from a bioenergetics perspective, metabolic reprogramming to a glycolytic state has been proposed as a mechanism which allows the allocation of glycolytic intermediates into biosynthetic pathways (Vander Heiden et al., 2009). Indeed, we have demonstrated the enhanced glycolytic flux is diverted into the nonoxidative PPP to facilitate ribose biogenesis. Furthermore, such hypotheses are also supported by the observation that amplification/overexpression of PHGDH, a rate-limiting enzyme functioning to divert 3-phospho-glycerate (a glycolytic intermediate) into the serine biosynthesis pathway, facilitates tumor growth in certain contexts (Locasale et al., 2011; Possemato et al., 2011).

The Activation of Hexosamine Biosynthesis and Glycosylation Pathways by KrasG12D

In this study, we provide evidence that oncogenic Kras plays a prominent role in the flux of glucose into the HBP. Our data shows that the expression of Gfpt1, the first and rate-limiting step of HBP, is strongly downregulated upon KrasG12D inactivation. The HBP is obligatory for various glycosylation processes, such as protein N- or O-glycosylation and glycolipid synthesis. Although its function during tumorigenesis is poorly understood, recent studies indicate that the HBP is important for the coordination of nutrient uptake, partially through modulating the glycosylation and membrane localization of growth factor receptors (Wellen et al., 2010). Protein and lipid glycosylation is an abundant posttranslational modification and plays fundamental regulatory roles in tumor cell proliferation, invasion/metastasis, angiogenesis, and immune evasion (Fuster and Esko, 2005; Hart and Copeland, 2010). Ras oncogenes have been shown to induce N-glycosylation and Kras mutation in human colorectal cancer cells is associated with increased N-linked carbohydrate branching (Bolscher et al., 1988; Dennis et al., 1989; Rak et al., 1991; Wojciechowicz et al., 1995). Here, we provided additional evidence that oncogenic Kras signaling also sustains protein O-glycosylation during tumor maintenance.

KrasG12D Induces Nonoxidative PPP Flux

The PPP is considered important for tumorigenesis as it provides NADPH for macromolecule biosynthesis and ROS detoxification, as well as ribose 5-phosphate for DNA/RNA synthesis (Boros et al., 1998; Deberardinis et al., 2008b). Additionally, it has been shown that the Ras oncogene promotes resistance to oxidative stress through GSH-based ROS scavenger pathways (DeNicola et al., 2011; Recktenwald et al., 2008), and this is likely mediated in part by the production of NADPH through the oxidative arm of the PPP. In fact, the oxidative arm of the PPP has been shown to be activated by Kras oncogene-mediated transformation to promote cell proliferation (Vizan et al., 2005; Weinberg et al., 2010). Notably, we did not observe obvious changes in the oxidative PPP but rather a role for oncogenic Kras signaling in the preferential maintenance of the nonoxidative arm of PPP. It has been recently shown that p53 inhibits G6PD activity through direct binding (Jiang et al., 2011). Therefore, it is possible that the oxidative PPP is largely regulated by p53 deficiency in PDAC tumor cells, whereas oncogenic signaling from KrasG12D sustains the nucleotide pool through de novo biosynthetic pathways. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that the nonoxidative PPP is preferentially upregulated in tumor cells including pancreatic cancer (Boros et al., 2005; Tong et al., 2009). Our data indicate that such metabolic changes are tightly regulated by oncogenic Kras and that suppression of the nonoxidative PPP blocks tumorigenic activity. These data suggest that inhibition of early steps of nucleotide biosynthesis, such as R5P production, could provide a useful therapeutic strategy for KrasG12D mutant tumors.

One interesting observation of KrasG12D-mediated metabolic reprogramming is the decrease in SBP upon KrasG12D inactivation. Interestingly, an enzyme was recently discovered in yeast that dephosphorylates SBP thereby providing the thermodynamic driving force for canonical F-type nonoxidative PPP flux independent of the oxidative arm (Clasquin et al., 2011). However, attempts at identifying a mammalian ortholog have been unsuccessful. Alternatively, SBP has also been reported to function in an alternative “L-type” PPP in liver that eventually feeds into the nonoxidative arm (Williams et al., 1987). Our finding provides a unique connection of this pathway to a driver oncogene and may provide a novel diagnostic and therapeutic avenue for these Ras-driven tumors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Plasmid Construct and Transgenic Mice

A fragment containing mutant murine KrasG12D cDNA (Johnson et al., 2001) was used to generate the tetO_Lox-Stop-Lox-KrasG12D transgene by standard cloning methods. The detailed method and additional alleles are described in Extended Experimental Procedures. All manipulations were performed under IACUC approval protocol number 04116.

Xenograft Studies

For orthotopic xenografts, 5 × 105 cells suspended in 10 μl 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences)/Hanks buffered saline solution were injected pancreatically into NCr nude mice (Taconic). Animals were fed with doxy water.

For Sub-Q xenografts, 1 × 106 cells suspended in 100 μl Hanks buffered saline solution were injected subcutaneously into the lower flank of NCr nude mice (Taconic). Animals were fed with doxy water. Tumor volumes were measured every 3 days starting from Day 4 postinjection and calculated using the formula, volume = length × width2/2. All xenograft experiments were approved under IACUC protocol 04114.

Immunohistochemistry and Western Blot Analysis

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin overnight and embedded in paraffin. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed as described (Aguirre et al., 2003). The primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry or western are listed in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Targeted Mass Spectrometry

The preparation and measurement of metabolites by LC-MS/MS are described in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Isotope Labeling and Kinetic Profiling

Glucose- or glutamine-free RPMI was supplemented with 10% dialyzed serum and 1,2-13C2-glucose, U-13C6-glucose, or U-13C5-glutamine (Cambridge Isotope Labs) to 11 mM (for glucose) or 2 mM (for glutamine). Cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr, at which point labeled media was added to biological triplicates. For glucose-flux analysis, cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr and then media was replaced with that containing U-13C6-glucose.

1-14C/6-14C Glucose Incorporation into Nucleotides

Cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr, at which point biological triplicates were treated with 1 μCi 1-14C or 6-14C glucose. Cells were harvested 24 hr later. DNA or RNA were isolated with QIAGEN kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using a NanoDrop instrument. Equal volumes of DNA/RNA were added to scintillation vials and radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting and normalized to the DNA/RNA concentration.

14C Glucose Incorporation into CO2

Cells were maintained in the presence or absence of doxy for 24 hr, at which point biological triplicates were treated with 1 μCi 1-14C or 6-14C glucose and incubated at 37°C for the indicated time points. To release 14CO2, 150 μl of 3 M perchloric acid was added to each well and immediately covered with phenyl-ethylamine saturated Whatman paper and incubated at room temperature overnight. The Whatman paper was then analyzed by scintillation counting.

Metabolite Analysis of Spent Medium

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates in triplicate for 24 hr followed by culture in doxy-free medium or medium containing doxy for additional 24 hr. Glucose and lactate concentrations were measured in fresh and spent medium using a Yellow Springs Instruments (YSI) 7100. Glucose data are presented as net decrease in concentration, and lactate as net increase in concentration after normalization to cell numbers.

Expression Profiling and Bioinformatics Analysis

mRNA expression profiling and data analysis are described in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Lentiviral-Mediated shRNA Targeting

Lentiviral shRNA clones targeting Gfpt1, Rpia, Rpe, and nontargeting control construct shGFP were obtained from the RNAi Consortium at the Dana-Farber/Broad Institute. The clone IDs for the shRNA are listed in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Statistical Analysis

Tumor-free survivals were analyzed using GraphPad Prism4. Statistical analyses were performed using nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Other comparisons were performed using the unpaired Student’s t test. For all experiments with error bars, standard deviation (SD) was calculated to indicate the variation within each experiment and data, and values represent mean ± SD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Wright for the p48-Cre mice; Shan Zhou and Shan Jiang for expert monitoring of the mouse colony; Yingchun Liu, Yuxiang Zheng, Ning Wu, Alexandra Grassian, Joan Brugge, Min Yuan, and Susanne Breitkopf for helpful suggestions and technical support. Grant support derives from NIH grants T32 CA009382-26 (H.Y.) and P01 CA117969 (R.W., L.C., L.C.C., R.A.D.). Imaging was supported by U24 CA092782 and P50 CA86355 (R.W.). Mass spectrometry was supported by 5P01CA120964-05 (L.C.C. and J.A.), 5P30CA006516-46 (J.A.), and the BIDMC Research Capital Fund. A.C.K. is supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant R01 CA157490, Kimmel Scholar Award and AACR-PanCAN Career Development Award. C.A.L. is the Amgen Fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-2056-10). S.H. is supported by a Damon Runyon Fellowship. A.C.K. is a Consultant for Forma Therapeutics. L.C.C. is a founder of Agios Pharmaceuticals, a company developing drugs to target metabolic enzymes for cancer therapy.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058.

References

- Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, Redston MS, DePinho RA. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3112–3126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belteki G, Haigh J, Kabacs N, Haigh K, Sison K, Costantini F, Whitsett J, Quaggin SE, Nagy A. Conditional and inducible transgene expression in mice through the combinatorial use of Cre-mediated recombination and tetracycline induction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolscher JG, van der Bijl MM, Neefjes JJ, Hall A, Smets LA, Ploegh HL. Ras (proto)oncogene induces N-linked carbohydrate modification: temporal relationship with induction of invasive potential. EMBO J. 1988;7:3361–3368. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros LG, Lee PW, Brandes JL, Cascante M, Muscarella P, Schirmer WJ, Melvin WS, Ellison EC. Nonoxidative pentose phosphate pathways and their direct role in ribose synthesis in tumors: is cancer a disease of cellular glucose metabolism? Med. Hypotheses. 1998;50:55–59. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(98)90178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros LG, Lerner MR, Morgan DL, Taylor SL, Smith BJ, Postier RG, Brackett DJ. [1,2-13C2]-D-glucose profiles of the serum, liver, pancreas, and DMBA-induced pancreatic tumors of rats. Pancreas. 2005;31:337–343. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000186524.53253.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L, Tam A, Pomerantz J, Wong M, Holash J, Bardeesy N, Shen Q, O’Hagan R, Pantginis J, Zhou H, et al. Essential role for oncogenic Ras in tumour maintenance. Nature. 1999;400:468–472. doi: 10.1038/22788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasquin MF, Melamud E, Singer A, Gooding JR, Xu X, Dong A, Cui H, Campagna SR, Savchenko A, Yakunin AF, et al. Riboneogenesis in yeast. Cell. 2011;145:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008a;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008b;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, Gopinathan A, Wei C, Frese K, Mangal D, Yu KH, Yeo CJ, Calhoun ES, et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JW, Kosh K, Bryce DM, Breitman ML. Oncogenes conferring metastatic potential induce increased branching of Asn-linked oligosaccharides in rat2 fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1989;4:853–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsher DW, Bishop JM. Reversible tumorigenesis by MYC in hematopoietic lineages. Mol Cell. 1999;4:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GH, Wellen SL, Klimstra D, Lenczowski JM, Tichelaar JW, Lizak MJ, Whitsett JA, Koretsky A, Varmus HE. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3249–3262. doi: 10.1101/gad.947701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Nakata K, Yu J, Kayashima T, Cui L, Manabe T, Ohtsuka T, Tanaka M. alpha-Smooth muscle actin expressing stroma promotes an aggressive tumor biology in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2010;39:1254–1262. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181dbf647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funes JM, Quintero M, Henderson S, Martinez D, Qureshi U, Westwood C, Clements MO, Bourboulia D, Pedley RB, Moncada S, Boshoff C. Transformation of human mesenchymal stem cells increases their dependency on oxidative phosphorylation for energy production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6223–6228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700690104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster MM, Esko JD. The sweet and sour of cancer: glycans as novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:526–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, Dang CV. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra C, Mijimolle N, Dhawahir A, Dubus P, Barradas M, Serrano M, Campuzano V, Barbacid M. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysin S, Salt M, Young A, McCormick F. Therapeutic strategies for targeting ras proteins. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:359–372. doi: 10.1177/1947601911412376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Copeland RJ. Glycomics hits the big time. Cell. 2010;143:672–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1218–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Du W, Wang X, Mancuso A, Gao X, Wu M, Yang X. p53 regulates biosynthesis through direct inactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:310–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Tuveson DA, Jacks T. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Cooper B, Gannon M, Ray M, MacDonald RJ, Wright CV. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nat Genet. 2002;32:128–134. doi: 10.1038/ng959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ, Puzio-Kuter AM. The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Science. 2010;330:1340–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1193494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locasale JW, Grassian AR, Melman T, Lyssiotis CA, Mattaini KR, Bass AJ, Heffron G, Metallo CM, Muranen T, Sharfi H, et al. Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase diverts glycolytic flux and contributes to oncogenesis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:869–874. doi: 10.1038/ng.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S, Vooijs M, van Der Gulden H, Jonkers J, Berns A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 2000;14:994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody SE, Sarkisian CJ, Hahn KT, Gunther EJ, Pickup S, Dugan KD, Innocent N, Cardiff RD, Schnall MD, Chodosh LA. Conditional activation of Neu in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice results in reversible pulmonary metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neesse A, Michl P, Frese KK, Feig C, Cook N, Jacobetz MA, Lolkema MP, Buchholz M, Olive KP, Gress TM, Tuveson DA. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2011;60:861–868. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato R, Marks KM, Shaul YD, Pacold ME, Kim D, Birsoy K, Se-thumadhavan S, Woo HK, Jang HG, Jha AK, et al. Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature. 2011;476:346–350. doi: 10.1038/nature10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racker E, Resnick RJ, Feldman R. Glycolysis and methylaminoisobutyrate uptake in rat-1 cells transfected with ras or myc oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3535–3538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rak JW, Basolo F, Elliott JW, Russo J, Miller FR. Cell surface glycosylation changes accompanying immortalization and transformation of normal human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Lett. 1991;57:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90059-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recktenwald CV, Kellner R, Lichtenfels R, Seliger B. Altered detoxification status and increased resistance to oxidative stress by K-ras transformation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10086–10093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart J, Adjei AA, Lorusso PM, Waterhouse D, Hecht JR, Natale RB, Hamid O, Varterasian M, Asbury P, Kaldjian EP, et al. Multi-center phase II study of the oral MEK inhibitor, CI-1040, in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4456–4462. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Settleman J. Oncogenic K-ras “addiction” and synthetic lethality. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2676–2677. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.17.9336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N, Settleman J. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek L, Whitfield J, Martins CP, Finch AJ, Murphy DJ, Sodir NM, Karnezis AN, Swigart LB, Nasi S, Evan GI. Modelling Myc inhibition as a cancer therapy. Nature. 2008;455:679–683. doi: 10.1038/nature07260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Zhao F, Thompson CB. The molecular determinants of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in cancer cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizan P, Boros LG, Figueras A, Capella G, Mangues R, Bassilian S, Lim S, Lee WN, Cascante M. K-ras codon-specific mutations produce distinctive metabolic phenotypes in NIH3T3 mice [corrected] fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5512–5515. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, Weinberg S, Joseph J, Lopez M, Kalyanaraman B, Mutlu GM, Budinger GR, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8788–8793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen KE, Lu C, Mancuso A, Lemons JM, Ryczko M, Dennis JW, Rabinowitz JD, Coller HA, Thompson CB. The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway couples growth factor-induced glutamine uptake to glucose metabolism. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2784–2799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1985910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JF, Arora KK, Longenecker JP. The pentose pathway: a random harvest. Impediments which oppose acceptance of the classical (F-type) pentose cycle for liver, some neoplasms and photosynthetic tissue. The case for the L-type pentose pathway. Int J Biochem. 1987;19:749–817. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(87)90239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang XY, Pfeiffer HK, Nissim I, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, McMahon SB, Thompson CB. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18782–18787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810199105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowicz DC, Park PY, Paty PB. Beta 1–6 branching of N-linked carbohydrate is associated with K-ras mutation in human colon carcinoma cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:758–766. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M, Breitkopt SB, Asara JM. A positive/negative switching targeted mass spectrometry based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, fresh and fixed tissue. Nat Protoc. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun J, Rago C, Cheong I, Pagliarini R, Angenendt P, Rajagopalan H, Schmidt K, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Zhou S, et al. Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science. 2009;325:1555–1559. doi: 10.1126/science.1174229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Capello M, Fredolini C, Piemonti L, Liotta LA, Novelli F, Petricoin EF. Proteomic analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells reveals metabolic alterations. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1944–1952. doi: 10.1021/pr101179t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.