Abstract

EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) is the catalytic subunit of PRC2 (polycomb repressive complex 2), which mediates histone methyltransferase activity and functions as transcriptional repressor involved in gene silencing. EZH2 is involved in malignant transformation and biological aggressiveness of several human malignancies. We previously demonstrated that non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) also overexpress EZH2 and that high expression of EZH2 correlates with poor prognosis. Growing evidence indicates that EZH2 may be an appropriate therapeutic target in malignancies, including NSCLCs. Recently, an S-adenosyl-L homocysteine hydrolase inhibitor, 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep), has been shown to deplete and inhibit EZH2. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of DZNep in NSCLC cells. Knockdown of EZH2 by small-interfering RNA (siRNA) resulted in decreased growth of four NSCLC cell lines. MTT assays demonstrated that DZNep treatment resulted in dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation in the NSCLC cell lines with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) ranging from 0.08 to 0.24 μM. Immortalized but non-cancerous bronchial epithelial and fibroblast cell lines were less sensitive to DZNep than the NSCLC cell lines. Soft agarose assays demonstrated that anchorage-independent growth was also reduced in all three NSCLC cell lines that were evaluated using this assay. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that DZNep induced apoptosis and G1 cell cycle arrest in NSCLC cells, which was partially associated with cyclin A decrease and p27Kip1 accumulation. DZNep depleted cellular levels of EZH2 and inhibited the associated histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation. These results indicated that an epigenetic therapy that pharmacologically targets EZH2 via DZNep may constitute a novel approach to treatment of NSCLCs.

Keywords: 3-deazaneplanocin A (DZNep), polycomb-group protein, EZH2, non-small cell lung cancer, epigenetics, proliferation, apoptosis

Introduction

Lung cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for more than 80% of all lung cancer cases. Despite some advances in early detection and recent improvements in treatment, the prognoses of patients with lung cancer remain poor [1, 2]. The current challenges are to identify new therapeutic targets and strategies and to incorporate these strategies into existing treatment regimens with the goal of improving treatment outcomes.

Epigenetic gene silencing is an important mechanism that causes loss of gene expression and that mediates, along with genetic mutation, the initiation and progression of human cancer [3]. Polycomb group (PcG) proteins regulate and mediate epigenetic transcriptional silencing. They are involved in the maintenance of embryonic and adult stem cells and in repression of key tumor-suppressor pathways, which might contribute to their oncogenic function [4]. The enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) is the catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which also includes the suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12) protein and embryonic ectoderm development (EED) protein. EZH2 acts as a histone lysine methyltransferase that mediates trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3) to silence expression of PRC2 target genes involved in lineage differentiation [5, 6].

EZH2 is overexpressed in a variety of malignancies including prostate cancer [7, 8], breast cancer [7, 9], melanoma [7], uterine cancer [7], gastric cancer [10], and renal cell cancer [11]. EZH2 expression levels are correlated with aggressiveness, metastasis, and a poor prognosis in most types of these cancers [7-11]. EZH2 is barely expressed in normal tissues of various types [12]. More recently, we found that NSCLCs also overexpress EZH2 and that high expression of EZH2 is correlated with poor prognosis [13]. Furthermore, an activating mutation in EZH2 has been identified in a subset of B-cell lymphomas [14]. Overexpression of EZH2 enhanced aggressiveness in prostatic cancer cells [15] and produced a neoplastic phenotype characterized by anchorage-independent growth and cell invasion in immortalized mammary epithelial cells and in bronchial epithelial cells [9, 16]. Conversely, depletion of EZH2 results in reduced proliferation, increased apoptosis, and inhibition of tumorigenicity in cancer cells [8, 15, 17, 18] including NSCLC cells [12, 19]. These findings indicate that EZH2 may be an appropriate therapeutic target in various types of cancers, including NSCLCs.

A cyclopentenyl analog of 3-deazaadenosine, 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep), inhibits the activity of S-adenosyl-L homocysteine (AdoHcy) hydrolase, the enzyme responsible for the reversible hydrolysis of AdoHcy to adenosine and homocysteine [20]. This inhibition results in the intracellular accumulation of AdoHcy, which leads to inhibition of the S-adenosyl-L-methionine–dependent lysine methyltransferase activity. Recently, DZNep was shown to reduce levels of the PRC2 complex, including EZH2, in breast cancer cells and cause concomitant loss of H3K27me3 and derepression of epigenetically silenced target genes [21]. Moreover, DZNep inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in several types of cancer cells [22-28]. Currently, however, data on the activity of DZNep in NSCLC cells are scarce. The aim of the present study was to assess the effects of DZNep on NSCLC cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagent

The four human NSCLC cell lines—NCI-H1299 (H1299), NCI-H1975 (H1975), and A549 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and PC-3 (Japan Cancer Research Resources Bank, Tokyo, Japan)—were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.03% glutamine at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The PC-3 cell line used in the study is not a prostate cancer cell line, but a NSCLC cell line with an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation, a deletion of exon 19 [29].

HBEC3 KT cell line was generously provided by John D Minna (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA). HBEC3 KT cell line was derived from primary human bronchial epithelial cells and immortalized by CDK4 and hTERT [30], and cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor and 50 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen Life Technologies) on collagen-coated dishes at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. 16HBE14o- cell line was kindly provided by Dieter C. Gruenert (University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA). 16HBE14o- cell line was derived from primary human bronchial epithelial cells and immortalized by SV40 large T antigen [31], and cultured in EMEM (Invitrogen Life Technologies) containing 10% FBS on collagen-coated dishes in a humidified incubator at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. WI-38 VA-13 2RA cell line (American Type Culture Collection) was human embryo lung fibroblast WI38 cell line immortalized by SV40 virus, and cultured in EMEM containing 10% FBS in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

DZNep was synthesized in the National Cancer Institute by Marquez, V.E.

Transfection of siRNAs

RNA interference of EZH2 was performed using 21-bp (including a 2-deoxynucleotide overhang) siRNA duplexes purchased from Ambion (s4916, Ambion Inc. Austin, TX, USA). An unrelated siRNA comprising a 19-bp scrambled sequence was used as the negative control siRNA. Transfection was carried out using 11 nM of the siRNA oligonucleotide duplexes and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were seeded at 500–3000 cells/well in 96-well plates in normal growth medium. Transfection was performed at a confluence of 30–50% with 11 nM of a siRNA and Lipofectamine 2000 reagent every 72. After 6 days, anchorage-dependent growth was measured in 96 well plates using an MTT (dimethyl thiozolyl-2′, 5′-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide)-based assay (CellTiter 96 non-radioactive cell proliferation assay, Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA). At least three independent experiments were performed to determine the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for each cell line. IC50 values were determined using Graphpad Prism 4.0c (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Anchorage-independent growth assays were performed using 0.4% soft agarose (Seaplaque, FMC Corp., Rockland, ME, USA) in 6 well plates with or without DZNep (200 nM, 1 μM) as previously described [32]. After 2 weeks of incubation, colonies were stained with p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and counted using NIH Image version 1.62 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were cultured in 100-mm plates. Transfections were performed at a confluence of 30–50% with 11 nM of a siRNA. After 72 hrs, cells were treated with trypsin, washed twice with PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol at –20°C. Fixed cells were subjected to centrifugation and then resuspended in 250 μg/ml RNase and 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma) to label the DNA. DNA content was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and two software packages: CellQuest 3.1 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) and ModFit LT 2.0 (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA).

Analysis of apoptosis

Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V and PI, using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). Briefly, cells were treated with trypsin, subjected to centrifugation at 1000 x g for 5 min, washed one time with ice-cold PBS, and then resuspended in 500 μl of binding buffer. Thereafter, 1.1 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 10 μl of PI were added to the cell suspensions, and the components were mixed for 15 min in the dark. The percentage of apoptotic cells was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data analysis was performed using CellQuest 3.1 (BD Pharmingen).

Western blotting

Cell lysates derived from each NSCLC cell line were prepared by disrupting the cells in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer [150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)], which was supplemented with 100 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cell lysates were subjected first to sonication and then centrifugation to remove debris; the protein concentration in each sample was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Samples containing equal amounts of protein were loaded onto gels, and the proteins in each sample were separated in 12% or 15% SDS gels; separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, St. Albans, UK), and the membranes were incubated with the following antibodies: anti-EZH2 (11/EZH2; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA, USA), anti-SUZ12 (clone 3C1.2, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), trimethyl-Histone H3 Lys 27 (07-449, Millipore), anti-EED (09-774, Millipore), cyclin A (H-432, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-p27 Kip1 (clone 57, BD Transduction Laboratories), and anti-actin (A-2066, Sigma-Aldrich Co.) antibodies. The primary antibodies were detected using anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (NA934V, NA931V, Amersham Biosciences); secondary antibodies were visualized using the Amersham ECL system after the membranes were washing with TBST six times (5 min each) after first and second antibodies incubation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between two groups was determined using unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-test. For multiple group comparison, statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. All tests were performed using SPSS software (version 18.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

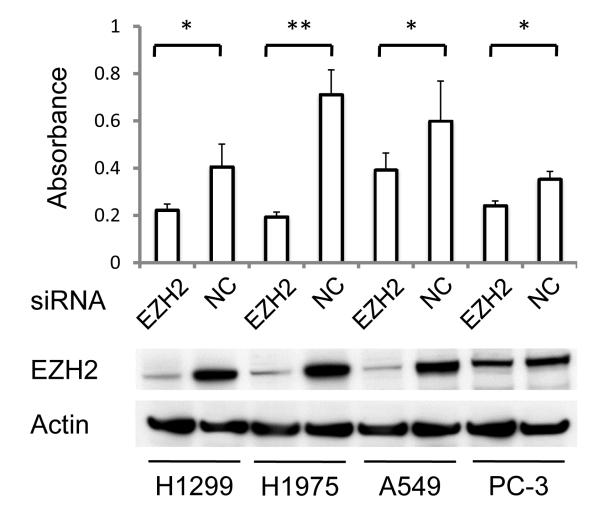

siRNA-mediated knockdown of EZH2 expression inhibited growth of NSCLC cells

We investigated whether siRNA-mediated knockdown of EZH2 inhibited growth in four NSCLC cell lines. Reductions in EZH2 protein expression in all four NSCLC cell lines—H1299, H1975, A549, and PC-3—were confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1). For each NSCLC cell line, cells transfected with EZH2 siRNA exhibited less cell proliferation than did cells transfected with negative control siRNA.

Fig. 1.

Effects of EZH2 knockdown on cell proliferation in NSCLC cell lines. NCI-H1299 (H1299), NCI-H1975 (H1975), A549, and PC-3 cells were transfected with EZH2 siRNA or a negative control siRNA every 72 h. After 6 days, cell proliferation was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Data are means ± SD of quadruplet samples in one of three independent experiments. Similar results were obtained from all three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and *p < 0.01 versus cells treated with negative control siRNA by unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-test. Cell lysates were collected 72 hrs after transfection with EZH2 or a negative control siRNA; lysates were subjected to western blot analysis. EZH2; transfected with EZH2 siRNA, NC; transfected with negative control siRNA.

DZnep inhibited growth of NSCLC cells

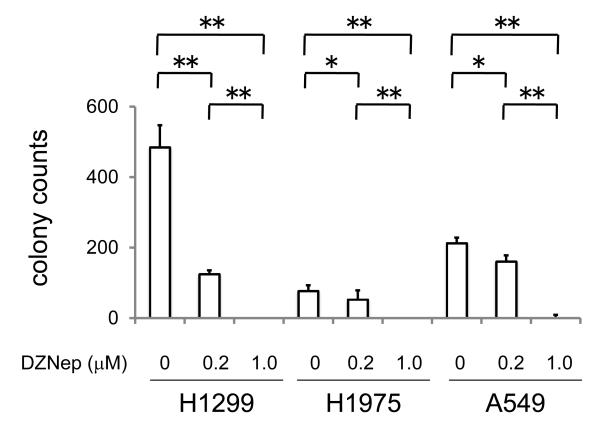

MTT assays demonstrated that DZNep caused dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation of NSCLC cell lines (Fig. S1), and the IC50 values ranged from 0.08 to 0.24 μM (Table 1). We also examined three immortalized but non-cancerous cell lines (HBEC3 KT, and 16HBE14o- bronchial epithelial cell lines and WI-38 VA-13 2RA fibroblast cell line). These cell lines also showed dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation by DZNep and had the IC50 values ranging from 0.54 to 1.03 μM, which were significantly higher than that of each NSCLC cell line (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Soft agarose assays showed that DZNep also reduced anchorage-independent growth in a dose-dependent fashion in all three NSCLC cell lines evaluated (Fig. 2). We excluded PC-3 cells from these assays because these cells did not form colonies within 4 weeks even in the absence of DZNep.

Table 1.

IC50 values of DZNep for the inhibition of proliferation in NSCLC and non-cancerous cell lines

| Cell type | Cell line | IC50 of DZNep (μM)* |

|---|---|---|

| NSCLC cells | H1299 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| H1975 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | |

| A549 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | |

| PC-3 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | |

| Non-cancerous cells | HBEC3 KT | 0.58 ± 0.09** |

| 16HBE14o- | 1.03 ± 0.11** | |

| WI-38 VA-13 2RA | 0.63 ± 0.07** |

Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

p < 0.001 compared with each NSCLC cell line by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of anchorage-independent growth by DZNep. Representative data from one of three independent experiments is shown. Data are means ± SD of triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained from all three independent experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 between indicated groups by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

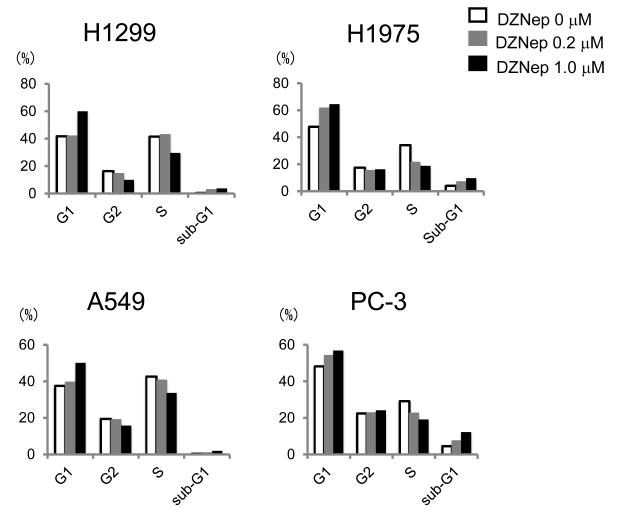

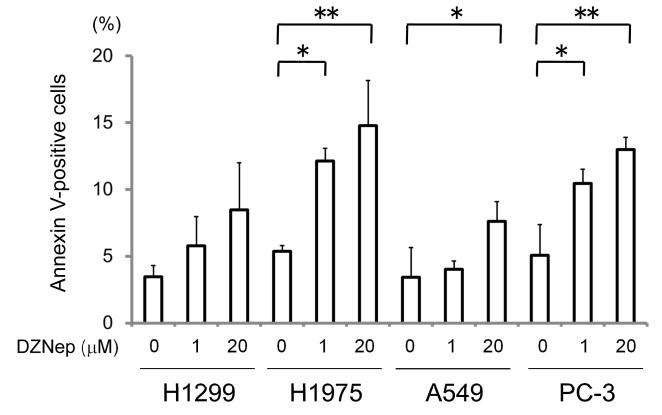

DZNep induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis

We used flow cytometry to determine whether the reduction in proliferation was due to cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in the four NSCLC cell lines. Treatment with DZNep at a concentration of 0.2 - 1.0 μM resulted in a slight increase in accumulation of cells in G1 phase of the cell cycle with a concomitant decrease in cells in S phase. The sub-G1 fraction also increased slightly following treatment with DZNep (Fig. 3). Flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V and PI demonstrated that the apoptotic fraction in each cell line increased in a dose-dependent manner following the treatment with DZNep; these effects were more evident in H1975 and PC-3 cells than in A549 cells and in H1299 cells, in which the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effect of DZNep on cell cycle in NSCLC cells. Cells were transfected with indicated doses of DZNep. After 72 hrs, the percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase was measured using a FACS flow cytometer and ModFitLT software. Representative data from one of three independent experiments is shown. Similar results were obtained in all three independent experiments.

Fig. 4.

Cell apoptosis analysis of NSCLC cells using flow cytometry with Annexin V-FITC and PI staining. Cells were treated with indicated doses of DZNep. After 72 hrs, the percentage of cells in the apoptotic fraction was measured using a FACS flow cytometer. Data are means ± SD of triplicate samples from one of three independent experiments. Similar results were obtained in all three independent experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 between indicated groups by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

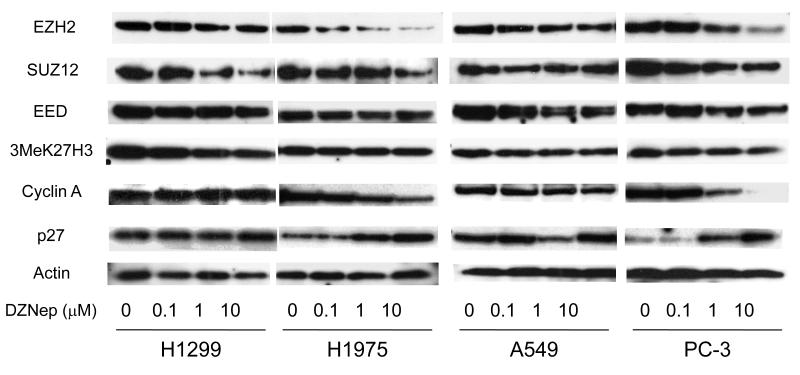

Treatment with DZNep depleted EZH2, SUZ12, EED, histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation and cyclin A, and increased p27kip1 in NSCLC cells

Treatment with DZNep results in reduced expression of three PRC2 proteins (EZH2, SUZ12 and EED) in breast and colon cancer cells [21]. Consistent with these previous findings, treatment with DZNep resulted in reduced expression of the EZH2, SUZ12, and EED proteins in all four NSCLC cell lines, while the degree of the reduction varied between proteins and cell lines (Fig. 5). We next determined the effects of DZNep on H3K27me3 (trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone H3). A slight reduction in the repressive H3K27me3 followed treatment with DZNep. DZNep induced dose-dependent accumulation of p27 Kip1 and decreases in cyclin A in H1975 and PC3 cells, while such effect was only slightly seen in H1299 and A549 cells.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis of NSCLC cells. Cell lysates were collected 72 hrs after the indicated doses of DZNep were administered; lysates were then subjected to western blot analysis. Representative western blots of EZH2, SUZ12, EED, trimethylation of lysine 27 on histon H3 (H3K27me3), cyclin A, p27 Kip1, and actin are shown.

Discussion

EZH2 overexpression correlates with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in a variety of malignancies including prostate, breast, uterine and gastric cancers [7-10]. Recently, we and others have shown that EZH2 is frequently overexpressed in NSCLCs and that high expression of EZH2 is correlated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis [13, 33]. Finding from the present study demonstrated that knockdown of EZH2 expression by siRNA reduced cell proliferation in four types of NSCLC cells, including A549 and H1299 cells, which were used in a previous study. In addition, our findings indicated that pharmacologic disruption of EZH2 via DZNep, which inhibits the histone methyltransferase EZH2, inhibited growth in four NSCLC cell lines in a dose-dependent manner with higher sensitivity than in non-cancerous cells; these findings were consistent with findings from previous studies on different types of tumors [22-28].

The reduction of PRC2 components (EZH2, SUZ12, and EED) and the associated H3K27me3 by DZNep were consistent with finding from previous studies [21, 27]. Meanwhile, DZNep was originally identified as an AdoHcy hydrolase inhibitor [20], which leads to the indirect inhibition of various S-adenosyl-methionine-dependent methylation reactions [34]. A recent study showed that DZNep globally decreases histone methylation including H3K9me3, H3K4me3 and H4K20me3, except for H3K9me3 and H3K36me3, suggesting histone methyltransferases other than EZH2 could be also susceptible to inhibition by DZNep [26]. Nevertheless, EZH2 knockdown alone caused significant inhibition of cell proliferation in all NSCLC cells in the present study, suggesting that the effect of DZNep are mediated by EZH2 depletion and the associated H3K27me3 reduction at least in part.

To our knowledge, the suppressive effects of DZNep on the proliferation of lung cancer cells have not been demonstrated previously, although DZNep has been shown to enhance deoxyazacytidine-mediated upregulation of some cancer-testis antigens in cells of lung cancers and to augment recognition and lysis of these cancer cells by T cells specific for these antigens [35]. Results of the cell cycle analysis in the present study indicated that the growth suppression by DZNep was associated with G1 cell cycle arrest in NSCLC cells; this conclusion is consistent with the findings from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells treated with DZNep [27]. Knockdown of EZH2 by siRNA has also been shown to induce G1 cell cycle arrest in Ras-transformed bronchial epithelial cells [16], A549 cells [12], and colon cancer cells [36]. Interestingly, DZNep induced decreases in cyclin A and accumulation of p27 Kip1 in H1975 and PC3 cells, but had minimal effects on these markers in the other two NSCLC cell lines. EZH2 is shown to reverse pRB2/p130-HDAC1 mediated transcriptional repression of cyclin A [37]. Genetic depletion of EZH2 results in reactivation of the p27 Kip1 gene in pancreatic cancer [17]. Association between either cyclin A repression or p27 Kip1 accumulation and G1 cell cycle arrest has been shown in various types of cells [38, 39]. Meanwhile, Fiskus et al. reported that DZNep treatment induces p16, p21, p27 Kip1, and FBXO32 while reducing cyclin E and HOXA9 levels in the human AML cells [27]. Taken together, these results indicate that growth suppression by DZNep was associated with G1 arrest in NSCLC cells, partly via cyclin A repression and p27 Kip1 accumulation, while different cell lines may employ distinct cellular programs in responding to DZNep.

Our finding that DZNep induced apoptosis was consistent with findings from previous studies of other types of cancer cells including breast, hepatoma, and AML cells [21, 24, 27]. Recently, Wu et al. reported that EZH2 directly inhibits E2F1-dependent apoptosis through epigenetically modulating Bim expression in A549 and H1299 NSCLC cells [19]; this finding is also consistent with our findings. Notably, the apoptotic response was distinct in gefitinib-sensitive PC-3 cells, which have an EGFR mutation (a deletion of exon 19), and in gefitinib-resistant H1975 cells, which have two EGFR mutations (L858R and T790M); this observation indicated that DZNep may be useful for treating NSCLCs that have an EGFR gene mutation, including gefitinib-resistant mutations. Recent evidence indicates that oncogenic RAS can activate EZH2 expression through MEK/ERK signaling [40]. Taking together, our results suggest that activating EGFR mutations, which often occur in NSCLCs, may activate EZH2 through RAS/MEK/ERK signaling and modulate apoptotic response by DZNep. Besides, PC-3 and H1975, in which DZNep-induced apoptosis was more evident, displayed strong EZH2 silencing upon DZNep treatment, suggesting that their strong apoptotic responses may be due to higher intracellular accumulation or less efficient degradation of DZNep. The precise mechanisms by which DZNep induced apoptosis in NSCLCs have yet to be determined.

In conclusion, we showed that, via G1 arrest and apoptosis, the histone methyltransferase EZH2 inhibitor, DZNep, inhibited growth in four different cell lines that represented different types of NSCLC cells. An epigenetic therapy that pharmacologically targets EZH2 may be a potent cancer therapeutic for treatment of NSCLCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This research was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The authors thank Namiko Sawada for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement None declared.

Conflict of Interest Statement All authors have no actual or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) their work.

Reference

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparmann A, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:846–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao R, Zhang Y. The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann IM, Halvorsen OJ, Collett K, Stefansson IM, Straume O, Haukaas SA, Salvesen HB, Otte AP, Akslen LA. EZH2 expression is associated with high proliferation rate and aggressive tumor subgroups in cutaneous melanoma and cancers of the endometrium, prostate, and breast. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:268–273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–629. doi: 10.1038/nature01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, Ghosh D, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Hayes DF, Sabel MS, Livant D, Weiss SJ, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11606–11611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsukawa Y, Semba S, Kato H, Ito A, Yanagihara K, Yokozaki H. Expression of the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 is correlated with poor prognosis in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:484–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagener N, Macher-Goeppinger S, Pritsch M, Husing J, Hoppe-Seyler K, Schirmacher P, Pfitzenmaier J, Haferkamp A, Hoppe-Seyler F, Hohenfellner M. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) expression is an independent prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:524. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takawa M, Masuda K, Kunizaki M, Daigo Y, Takagi K, Iwai Y, Cho HS, Toyokawa G, Yamane Y, Maejima K, Field HI, Kobayashi T, Akasu T, Sugiyama M, Tsuchiya E, Atomi Y, Ponder BA, Nakamura Y, Hamamoto R. Validation of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 as a therapeutic target for various types of human cancer and as a prognostic marker. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1298–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi J, Kinoshita I, Shimizu Y, Kikuchi E, Konishi J, Oizumi S, Kaga K, Matsuno Y, Nishimura M, Dosaka-Akita H. Distinctive expression of the polycomb group proteins Bmi1 polycomb ring finger oncogene and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in nonsmall cell lung cancers and their clinical and clinicopathologic significance. Cancer. 2010;116:3015–3024. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCabe MT, Graves AP, Ganji G, Diaz E, Halsey WS, Jiang Y, Smitheman KN, Ott HM, Pappalardi MB, Allen KE, Chen SB, Della Pietra A, 3rd, Dul E, Hughes AM, Gilbert SA, Thrall SH, Tummino PJ, Kruger RG, Brandt M, Schwartz B, Creasy CL. Mutation of A677 in histone methyltransferase EZH2 in human B-cell lymphoma promotes hypertrimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:2989–2994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116418109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karanikolas BD, Figueiredo ML, Wu L. Comprehensive evaluation of the role of EZH2 in the growth, invasion, and aggression of a panel of prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2010;70:675–688. doi: 10.1002/pros.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe H, Soejima K, Yasuda H, Kawada I, Nakachi I, Yoda S, Naoki K, Ishizaka A. Deregulation of histone lysine methyltransferases contributes to oncogenic transformation of human bronchoepithelial cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2008;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ougolkov AV, Bilim VN, Billadeau DD. Regulation of pancreatic tumor cell proliferation and chemoresistance by the histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homologue 2. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6790–6796. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagener N, Holland D, Bulkescher J, Crnkovic-Mertens I, Hoppe-Seyler K, Zentgraf H, Pritsch M, Buse S, Pfitzenmaier J, Haferkamp A, Hohenfellner M, Hoppe-Seyler F. The enhancer of zeste homolog 2 gene contributes to cell proliferation and apoptosis resistance in renal cell carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1545–1550. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu ZL, Zheng SS, Li ZM, Qiao YY, Aau MY, Yu Q. Polycomb protein EZH2 regulates E2F1-dependent apoptosis through epigenetically modulating Bim expression. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:801–810. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glazer RI, Hartman KD, Knode MC, Richard MM, Chiang PK, Tseng CK, Marquez VE. 3-Deazaneplanocin: a new and potent inhibitor of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase and its effects on human promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL-60. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:688–694. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan J, Yang X, Zhuang L, Jiang X, Chen W, Lee PL, Karuturi RK, Tan PB, Liu ET, Yu Q. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb-repressive complex 2-mediated gene repression selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1050–1063. doi: 10.1101/gad.1524107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp CD, Rao M, Xi S, Inchauste S, Mani H, Fetsch P, Filie A, Zhang M, Hong JA, Walker RL, Zhu YJ, Ripley RT, Mathur A, Liu F, Yang M, Meltzer PA, Marquez VE, De Rienzo A, Bueno R, Schrump DS. Polycomb Repressor Complex-2 Is a Novel Target for Mesothelioma Therapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;18:77–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crea F, Hurt EM, Mathews LA, Cabarcas SM, Sun L, Marquez VE, Danesi R, Farrar WL. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 inhibits tumorigenicity and tumor progression in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden A, Johnson PW, Packham G, Crabb SJ. S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibition by 3-deazaneplanocin A analogues induces anti-cancer effects in breast cancer cell lines and synergy with both histone deacetylase and HER2 inhibition. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suva ML, Riggi N, Janiszewska M, Radovanovic I, Provero P, Stehle JC, Baumer K, Le Bitoux MA, Marino D, Cironi L, Marquez VE, Clement V, Stamenkovic I. EZH2 is essential for glioblastoma cancer stem cell maintenance. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9211–9218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda TB, Cortez CC, Yoo CB, Liang G, Abe M, Kelly TK, Marquez VE, Jones PA. DZNep is a global histone methylation inhibitor that reactivates developmental genes not silenced by DNA methylation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1579–1588. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiskus W, Wang Y, Sreekumar A, Buckley KM, Shi H, Jillella A, Ustun C, Rao R, Fernandez P, Chen J, Balusu R, Koul S, Atadja P, Marquez VE, Bhalla KN. Combined epigenetic therapy with the histone methyltransferase EZH2 inhibitor 3-deazaneplanocin A and the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat against human AML cells. Blood. 2009;114:2733–2743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang X, Tan J, Li J, Kivimae S, Yang X, Zhuang L, Lee PL, Chan MT, Stanton LW, Liu ET, Cheyette BN, Yu Q. DACT3 is an epigenetic regulator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer and is a therapeutic target of histone modifications. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai Y, Miyazawa H, Huqun, Tanaka T, Udagawa K, Kato M, Fukuyama S, Yokote A, Kobayashi K, Kanazawa M, Hagiwara K. Genetic heterogeneity of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines revealed by a rapid and sensitive detection system, the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid PCR clamp. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7276–7282. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez RD, Sheridan S, Girard L, Sato M, Kim Y, Pollack J, Peyton M, Zou Y, Kurie JM, Dimaio JM, Milchgrub S, Smith AL, Souza RF, Gilbey L, Zhang X, Gandia K, Vaughan MB, Wright WE, Gazdar AF, Shay JW, Minna JD. Immortalization of human bronchial epithelial cells in the absence of viral oncoproteins. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9027–9034. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cozens AL, Yezzi MJ, Kunzelmann K, Ohrui T, Chin L, Eng K, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, Gruenert DC. CFTR expression and chloride secretion in polarized immortal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:38–47. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.7507342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabichi AL, Hendricks DT, Bober MA, Birrer MJ. Retinoic acid receptor beta expression and growth inhibition of gynecologic cancer cells by the synthetic retinoid N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:597–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huqun, Ishikawa R, Zhang J, Miyazawa H, Goto Y, Shimizu Y, Hagiwara K, Koyama N. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 is a novel prognostic biomarker in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiang PK. Biological effects of inhibitors of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao M, Chinnasamy N, Hong JA, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Xi S, Liu F, Marquez VE, Morgan RA, Schrump DS. Inhibition of histone lysine methylation enhances cancer-testis antigen expression in lung cancer cells: implications for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4192–4204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fussbroich B, Wagener N, Macher-Goeppinger S, Benner A, Falth M, Sultmann H, Holzer A, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F. EZH2 depletion blocks the proliferation of colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tonini T, Bagella L, D’Andrilli G, Claudio PP, Giordano A. Ezh2 reduces the ability of HDAC1-dependent pRb2/p130 transcriptional repression of cyclin A. Oncogene. 2004;23:4930–4937. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girard F, Strausfeld U, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ. Cyclin A is required for the onset of DNA replication in mammalian fibroblasts. Cell. 1991;67:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Resnitzky D, Hengst L, Reed SI. Cyclin A-associated kinase activity is rate limiting for entrance into S phase and is negatively regulated in G1 by p27Kip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4347–4352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujii S, Fukamachi K, Tsuda H, Ito K, Ito Y, Ochiai A. RAS oncogenic signal upregulates EZH2 in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:1074–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.