Abstract

Individual sites of superoxide production in the mitochondrial respiratory chain have previously been defined and partially characterized using specific inhibitors, but the native contribution of each site to total superoxide production in the absence of inhibitors is unknown. We estimated rates of superoxide production (measured as H2O2) at different sites in rat muscle mitochondria using specific endogenous reporters. The rate of superoxide production by the complex I flavin (site IF) was calibrated to the reduction state of endogenous NAD(P)H. Similarly, the rate of superoxide production by the complex III site of quinol oxidation (site IIIQo) was calibrated to the reduction state of endogenous cytochrome b566. We then measured the endogenous reporters in mitochondria oxidizing NADH-generating substrates, without added respiratory inhibitors, with and without ATP synthesis. We used the calibrated reporters to calculate the rates of superoxide production from sites IF and IIIQo. The calculated rates of superoxide production accounted for much of the measured overall rates. During ATP synthesis, site IF was the dominant superoxide producer. Under non-phosphorylating conditions, overall rates were higher and sites IF, IIIQo and unidentified sites (perhaps the complex I site of quinone reduction, site IQ) all made substantial contributions to measured H2O2 production.

Keywords: mitochondria, ROS, superoxide, complex I, complex III, NADH autofluorescence, cytochrome b.

Production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 has been implicated in many detrimental or degenerative biological processes. A truncated list includes metabolic diseases [1;2], neurodegenerative diseases [3], and cancers [4]. Mitochondrial ROS production has been asserted to play a fundamental role in the aging process, although this remains contentious [5–9]. There is increasing evidence that ROS are also crucial signalling molecules in many important physiological pathways [10]. The increasing number of physiological and pathological hypotheses that cite ROS production as crucial to their mechanism brings the question of physiological ROS production into focus. What are the native rates of mitochondrial ROS production in isolated mitochondria (i.e. the rates in the absence of added electron transport chain inhibitors)? What are these native rates in cells, or in vivo? What controls these rates? Is there one site in the electron transport chain of mitochondria that is responsible for most of the ROS production in cells? Do the rates of production differ with substrate and tissue type?

Chance and colleagues [11–13] established that isolated mitochondria can produce H2O2 in vitro. It is now appreciated that most of this H2O2 is formed as superoxide, and superoxide dismutase-2 [14] in the matrix converts it to H2O2, which can escape and be assayed in the surrounding medium. The field has subsequently expanded considerably and many characteristics of H2O2 production by mitochondria have been revealed. Using respiratory chain inhibitors to manipulate the reduction state of sites under investigation and to prevent superoxide generation from other sites, at least eight specific sites of superoxide and H2O2 production in the Krebs cycle and the electron transport chain of mammalian mitochondria have been identified or suggested, and partially characterized. These sites are α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; pyruvate dehydrogenase; glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; the electron transferring flavoprotein:Q oxidoreductase (ETFQOR) of fatty acid β-oxidation; the flavin in complex I (site IF); the ubiquinone-reducing site in complex I (site IQ); the ubiquinol-oxidizing site in complex III (site IIIQo) [15–17]; and complex II, which can generate large amounts of superoxide and/or H2O2 under appropriate conditions [18].

Despite the importance ascribed to mitochondria as a source of ROS, it is still unknown which enzymes or respiratory complexes are the main sources of superoxide or H2O2 production by mitochondria in vivo, in situ in cells, or in vitro [16;17]. This is because inhibiting or genetically modifying a candidate site interrupts normal electron flow and alters the redox states of remaining sites, and can dramatically alter their rates of superoxide or H2O2 production. This raises the question: how can the individual contributions from a complex suite of ROS-producing sites be assessed within intact mitochondria?

In the present paper we introduce and exploit a novel method of estimating the rates of superoxide generation from two specific sites by calibrating the reduction state of endogenous redox pools to the rate of superoxide generated from that site (the redox state of endogenous NAD(P)H to report site IF, and the redox state of cytochrome b566 to report site IIIQo), which we call endogenous reporters here. We describe the calibration of the reporters, then present the first quantitative estimate of the contributions of site IF and site IIIQo to total H2O2 production by isolated mitochondria under native conditions in the absence of respiratory chain inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, reagents and mitochondrial preparation

Female Wister rats (Harlan Laboratories), age 5–8 weeks, were fed chow ad libitum with free access to water. Skeletal muscle mitochondria were isolated at 4 °C in Chappell-Perry buffer (CP1; 100 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris, 2 mM EGTA, pH 7.1 at 25 °C) by standard procedures [19]. They had robust respiratory control ratios (3–4.5) for six hours after isolation, and we generally completed all assays in under four hours. The animal protocol was approved by the Buck Institute Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with IACUC standards. All reagents were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) except Amplex UltraRed, which was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Superoxide Production

Rates of superoxide production were measured indirectly as rates of H2O2 production following dismutation of two superoxide molecules by endogenous or exogenous superoxide dismutase (SOD) to yield one H2O2. H2O2 was detected using exogenous horseradish peroxidase and Amplex UltraRed [20]. Peroxidase activity associated with exogenous SOD was negligible compared to the added horseradish peroxidase activity, since SOD addition did not decrease the observed rate of H2O2 production when site IF was driven by malate in the presence of rotenone. Where there is clear evidence that the initial species formed at a site is superoxide, as there is for sites IF [21] and IIIQo [22], we refer to it throughout the present paper as ‘superoxide production’. Where it is not known or ambiguous whether a site generates superoxide or H2O2, as it is for site IQ, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase [23–25], and also where the sites involved are not fully defined, we refer to it as ‘superoxide/H2O2 production’. Where we discuss purely the experimental measurement we refer to it as ‘H2O2 production’. Where we discuss effects of the various species produced by mitochondria, including superoxide, H2O2, and their downstream products such as hydroxyl radical and lipid peroxides, we refer to them collectively as ‘ROS’.

Mitochondria (0.3 mg protein • ml−1) were suspended in medium at 37 °C containing 120 mM KCl, 5 mM Hepes, 5 mM K2PO4, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (pH 7.0 at 37 °C), together with 5 U·ml−1 horseradish peroxidase, 25 U • ml−1 SOD and 50 μM Amplex UltraRed. Where indicated, phosphorylating (“state 3”) conditions of ATP synthesis were established by adding an ADP regenerating system containing 0.1 mM ADP, 2.5 units • ml−1 hexokinase, and 20 mM glucose. Non-phosphorylating (“state 4”) conditions were established by adding 0.1 μg-ml−1 oligomycin. Reactions were monitored fluorometrically in a Shimadzu RF5301-PC or Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (λexcitation = 560 nm, λemission = 590 nm) with constant stirring, and calibrated with known amounts of H2O2 [19]. After addition of substrate at 5 minutes, linear rates of change were monitored between minutes 6.5 and 8; the background rate of change of Amplex UltraRed fluorescence was corrected for by subtracting the rate preceding substrate addition between minutes 4 and 5 (as illustrated in Fig. 4a).

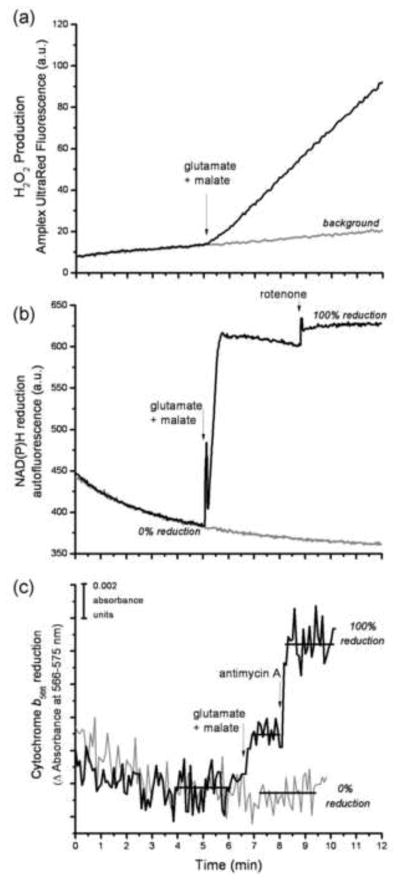

FIGURE 4. Design of the reporter-based superoxide assay.

The assay was designed to measure the rate of H2O2 production using Amplex UltraRed, and the steady-state reduction levels of NAD(P)H and cytochrome b566 under closely similar conditions. The timing of all additions was synchronized between the three assays. The addition of substrate, in this case 5 mM glutamate plus 5 mM malate, led to an increased rate of change of Amplex UltraRed fluorescence (a), and increased steady-state reduction levels of both NAD(P)H (b) and cytochrome b566 (c). The gray traces in each graph show the control in the absence of substrates or inhibitors. The 100% value for each reporter in (b) and (c) was established by addition of its relevant downstream inhibitor (4 μM rotenone or 2 μM antimycin A), as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The horizontal bars in (c) indicate the regions of data that were averaged to give the mean value used to calculate the % reduction of cytochrome b566. All of the data for the calibration curves (Figs 5 and 7) and measurements of native rates (Fig. 8) were collected in essentially this way.

NAD(P)H measurements

Experiments were performed using 0.3 mg mitochondrial protein·ml−1 at 37 °C in parallel with measurements of H2O2 and cytochrome b566 in the same medium with the same additions. The reduction state of endogenous NAD(P)H was determined by autofluorescence [26] using a Shimadzu RF5301-PC or Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer at λexcitation = 365 nm, λemission = 450 nm. NAD(P)H was assumed to be 0% reduced after 5 min without added substrate (the small apparent further oxidation of NAD(P)H in the absence of added substrate was ignored; this caused a small overestimate of NAD(P)H reduction state, but did not affect the reported rates of H2O2 production by site IF since the overestimate affected both assay and calibration equally) and 100% reduced with 5 mM malate and 4 μM rotenone (Fig. 4b). Intermediate values were determined as %NAD(P)H relative to the 0% and 100% values.

Cytochrome b566 measurements

Experiments were performed at 1.5 mg mitochondrial protein·ml−1 in parallel with measurements of H2O2 and NAD(P)H in the same medium. The reduction state of endogenous cytochrome b566 was measured with constant stirring at 37 °C in an Olis DW-2 dual wavelength spectrophotometer at 566–575 nm. The signal at this wavelength pair reports ~75% cytochrome b566 and ~25% cytochrome b562 [20;27]. We did not correct for the b562 contribution because the combined signal led to the same interpretations as the corrected signal, and less protein was required for each assay. Cytochrome b566 was assumed to be 0% reduced after 5 min without added substrate and 100% reduced with saturating substrates plus antimycin A (Fig. 4c). Intermediate values were determined as %b566 reduced relative to the 0% and 100% values. At least 15 consecutive data points were used to calculate the average %reduction in each condition. Reduction of cytochrome b562 was measured at 561–569 nm [27].

Protonmotive force and respiration measurements

Protonmotive force was assayed as mitochondrial membrane potential (in the presence of nigericin to abolish pH gradients), using an electrode sensitive to the membrane-permeant cationic probe, methyltriphenylphosphonium [19]. This gave minimum values for the normal steady state, because nigericin slightly inhibited substrate oxidation. Mitochondrial respiration was measured in parallel in a Clark-type oxygen electrode (in the absence of nigericin). Mitochondria were incubated under identical conditions to the H2O2 assays at 37 °C. The four experimental conditions in Fig. 8 generated the following protonmotive force values and respiration rates (mean ± SEM of three biological replicates). (a) 5 mM malate, phosphorylating: 140 ± 5 mV, 89 ± 40 nmol O min−1 • mg protein−1; (b) 5 mM malate, non-phosphorylating: 165 ± 1 mV, 28 ± 3 nmol O min−1 • mg protein−1; (c) 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate, phosphorylating: 158 ± 3 mV, 222 ± 29 nmol O min−1 • mg protein−1; (d) 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate, non-phosphorylating: 183 ± 2 mV, 48 ± 10 nmol O min−1 • mg protein−1.

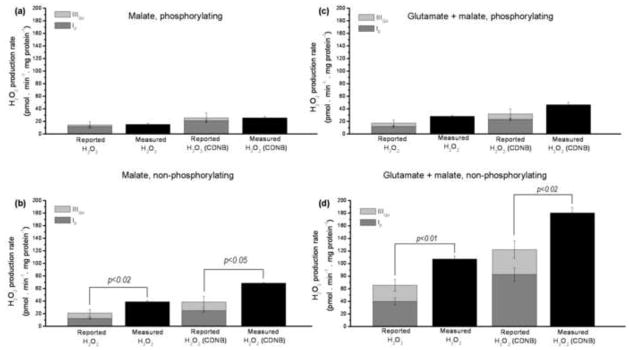

FIGURE 8. Reported and measured native rates of superoxide and H2O2 production by mitochondria oxidizing NAD-linked substrates in the absence of electron transport chain inhibitors.

Data from Table 2. (a) 5 mM malate as substrate under phosphorylating conditions. (b) 5 mM malate under non-phosphorylating conditions. (c) 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate under phosphorylating conditions. (d) 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate under non-phosphorylating conditions. The two left-hand bars in each panel show results for control mitochondria; the two right hand bars show results for CDNB-treated mitochondria. Reported rates from site IF are in dark grey; those from site IIIQo are in light grey. Black bars represent measured rates. Data are means ± SEM (n = 6). SEM values for reported rates were determined by error propagation; significance was tested using Welch’s t-test, see MATERIALS AND METHODS.

CDNB treatment and calibration

To allow correction for losses of H2O2 caused by peroxidase activity in the matrix, mitochondria were treated where stated with 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) to deplete glutathione and decrease glutathione peroxidase and peroxiredoxin activity [26]. In a previous publication [26], we performed the appropriate controls in skeletal muscle mitochondria to show that this protocol does not damage respiratory chain components and introduce artifactual H2O2 production, nor does it have measurable effects on the redox state of the NAD(P)H pool. Mitochondria (5 mg protein·ml−1) were treated with 35 μM CDNB or ethanol control in CP1 medium for 5 min at room temperature, mixed with an equal volume of ice-cold CP1 and centrifuged for 5 min at 15 000 g (at 2–4 °C). The pellet was washed twice in ice-cold CP1 and resuspended to approximately 30 mg protein·ml−1.

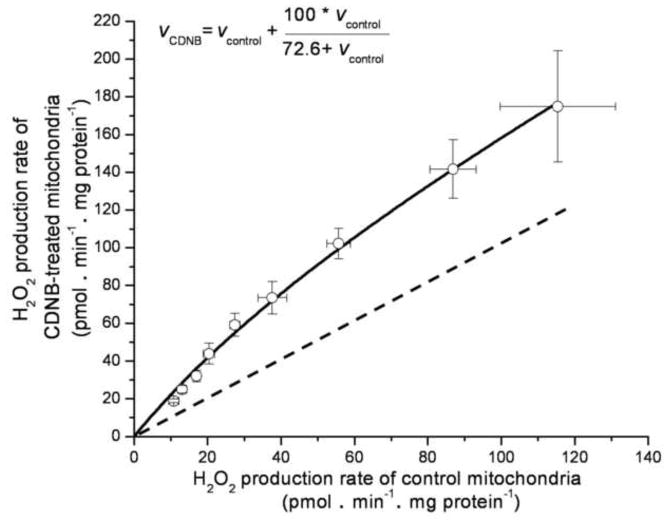

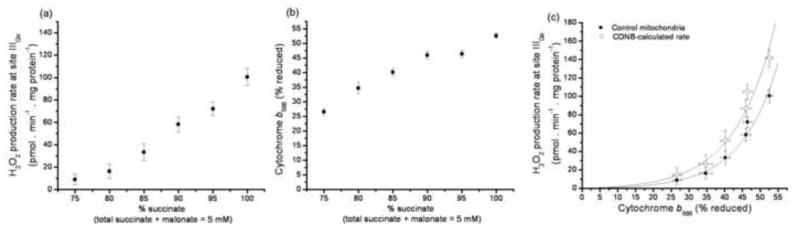

The CDNB correction curve (Fig. 1) was determined as described [26], but with improved accuracy at low H2O2 production rates. The previous correction curve [26] utilized rates from 0.25–1.5 nmol H2O2 • min−1 • mg protein−1 in a medium lacking phosphate and magnesium. We generated a new CDNB-correction curve in the current medium, at rates below 0.1 nmol H2O2 • min−1 • mg protein−1, by titrating malate into CDNB and ethanol-control treated mitochondria. The rates of H2O2 production were measured after the addition of 4 μM rotenone and assumed to be purely matrix-directed. The empirically-derived hyperbolic equation that described this relationship was:

| (Eq. 1) |

FIGURE 1. Comparison of rates of superoxide production (measured as H2O2 production) by site IF in CDNB-pretreated and control mitochondria.

Site IF was titrated by adding malate from 0.01 mM to 5 mM in separate runs followed by addition of rotenone. Points were fitted to give the parameter values in Eq. 1 (inset). The dashed line indicates a 1:1 relationship. Values are means ± SEM (n = 5).

(rates in pmol H2O2 • min−1 • mg protein−1). We emphasize that this relationship should be empirically determined for any new experimental condition and within the relevant data range.

Curve fitting

The control data for the IF calibration curve (Fig. 5c) were fitted by non-linear regression to a single exponential, to give the parameter values in Eq. 2:

| (Eq. 2) |

where vH2O2 is the rate of H2O2 production.

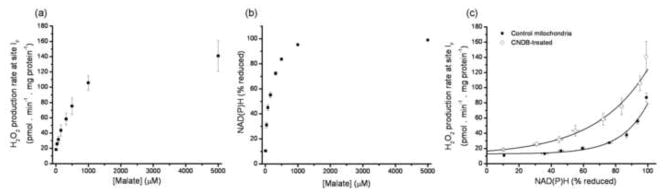

FIGURE 5. Relationship between the rate of superoxide production by site IF and the reduction state of NAD(P)H.

(a) Dependence of the rate of H2O2 production on malate concentration after addition of 4 μM rotenone. (b) Dependence of %NAD(P)H reduction on malate concentration after addition of rotenone (100% reduction was subsequently established by addition of 5 mM malate). (c) Final calibration of the relationship between the rate of superoxide production from site IF and NAD(P)H reduction state, obtained by combining panels (a) and (b). Filled symbols: control mitochondria; open symbols: CDNB-treated mitochondria (underlying data for CDNB-treated mitochondria is not shown). Where not visible, error bars are contained within the points. Lines show exponential relationships (for simplicity), fitted by non-linear regression to give the parameter values in Eq. 2. See MATERIALS AND METHODS. Data are means ± SEM (n = 6).

The control data for the IIIQo calibration curve (Fig. 7c) were fitted in the same way to give the parameter values in Eq. 3.

FIGURE 7. Relationship between the rate of superoxide production by site IIIQo and the reduction state of cytochrome b566.

(a) Dependence of the rate of myxothiazol-sensitive H2O2 production on succinate concentration at fixed succinate+malonate concentration in the presence of rotenone. Data were corrected for the contribution of site IF (Fig. 6c and Fig. 5c). (b) Dependence of cytochrome b566 reduction on succinate concentration in parallel incubations (100% reduction was subsequently established by addition of 2 μM Antimycin A). (c) Final calibration of the relationship between the rate of superoxide production from site IIIQo and cytochrome b566 reduction state, obtained by combining panels (a) and (b). Filled symbols: control mitochondria; open symbols: control values after correction to CDNB-treated mitochondria using Eq. 1, assuming that 50% of superoxide from site IIIQo was produced in the matrix (see [26]). Where not visible, error bars are contained within the points. Lines show exponential relationships (for simplicity), fitted by non-linear regression to give the parameter values in Eq. 3. See MATERIALS AND METHODS. Data are means ± SEM (n = 9).

| (Eq. 3) |

Data for CDNB-treated mitochondria were fitted in the same way (parameter values not shown).

Statistics

When using the calibration curves in Figs 5c and 7c to calculate rates of H2O2 production, the error in the measurements during calibration was taken into account. This error was calculated by error propagation using Eq. 4.

| (Eq. 4) |

For the data in Fig. 8, this error was combined with the error in the level of the measured reporter (Table 1) using Eq. 5:

| (Eq. 5) |

TABLE 1.

Reduction level of the reporters for sites IF and IIIQo in four different experimental conditions. The redox states of NAD(P)H and cytochrome b566 were determined in parallel as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

| Substrate, experimental condition | IF reporter (%reduced NAD(P)H) | IIIQo reporter (%reduced cytochrome b566) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 mM malate, phosphorylating | 20±1 | 16±2 |

| 5 mM malate, non-phosphorylating | 30±2 | 27±7 |

| 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate, phosphorylating | 26±1 | 23±3 |

| 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate, non-phosphorylating | 85±7 | 38±5 |

Values are means ± SEM, n = 6.

The sums of the reported rates of H2O2 production were calculated with Eq. 6:

| (Eq. 6) |

The significance of differences between reported and experimentally measured rates of H2O2 production in each experimental condition was tested using Welch’s t-test. Because error propagation was used to include uncertainty in the calibration curve, we could not enter individual data-points for statistical analysis. Instead we used the traits describing the population of data (mean, SEM based on error propagation and number of observations) to calculate if differences were significant (p <0.05).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Endogenous reporters of the rates of mitochondrial superoxide and H2O2 production

The rate of superoxide/H2O2 production at each individual site in the electron transport chain will be a function of the concentrations of the electron donor (i.e. the reduction state of the specific centre that donates its electron to oxygen), and electron acceptor (oxygen), and the appropriate rate constants for the reaction.

Despite earlier assumptions to the contrary, e.g. [29], all sites of superoxide/H2O2 production have similar hyperbolic responses to increasing oxygen concentrations and exhibit saturation kinetics, with little change in production rate above about 10 μM O2 at standard pressure [30]. In our air-saturated, open-cuvette experiments, the O2 concentration was about 200 μM, so the rate of production at any site will be a function of the concentration of the reduced electron donor and not rate limited by [O2]. For our analysis, the function relating the redox state of the donor to the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production has to be unique, but its other properties do not matter.

The redox states of the particular electron donors at each site may not be readily measureable. However, any electron carrier that is close to redox equilibrium with the donor will be a reporter of the donor’s redox state. Such a reporter can be used to construct an empirical calibration curve that describes how the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production from a site is related to the reduction state of the reporter. For our analysis, the relationship between the redox states of the reporter and the donor needs to be unique, but its other properties do not matter. However, if the reporter is close to equilibrium with the donor, their redox states will be related by the Nernst equation and can be modelled using exponentials. Even if there are complications (such as significant disequilibrium between donor and reporter or more complex kinetic interactions within a redox site), as long as the reporter has a unique relationship to the superoxide/H2O2 production rate in the range of conditions to be investigated, it can still be used.

Therefore, if there are unique relationships between the redox states of the reporter and the donor, and between the redox state of the donor and the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production, an empirical calibration of H2O2 production as a function of the redox state of the reporter can be used to predict the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production from any site with a suitable reporter. This is the basis of the method we introduce in the present paper to measure the native rates of superoxide production from different sites in the electron transport chain of isolated mitochondria in the absence of added inhibitors of electron transport. Fig. 2 depicts the principles and assumptions employed in using endogenous reporters of superoxide production rate in this way.

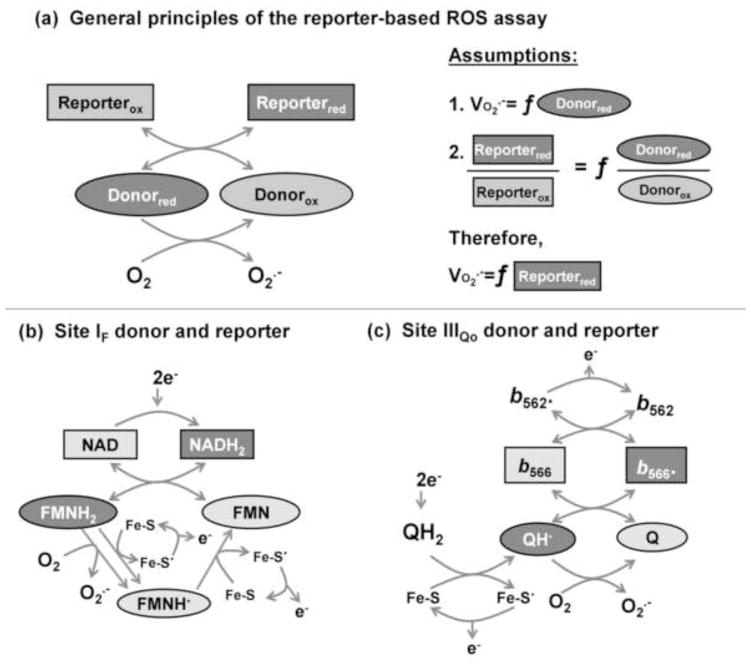

FIGURE 2. The theory and assumptions of the reporter-based assay of superoxide production rate.

(a) Theory. When the donor species in a superoxide-producing site (ovals) is reduced (darker shading) it donates electrons to oxygen to generate superoxide. The redox state of the donor is reported by an adjacent redox centre (rectangles). Two primary assumptions are made. First, the rate of superoxide production is a unique function (f) of the reduction state of the donor (in the simplest case, the rate of superoxide production is the product of a pseudo first-order rate constant and the concentration or % reduction of the donor). Second, the reduction state of a relevant, nearby reporter is a unique function of the reduction state of the donor (in the simplest case the two centres are at equilibrium and their redox states are related by the Nernst equation). It follows that the rate of superoxide production will be a unique function of the reduction state of the reporter (in the simplest case, that function can be derived from the two simplest cases above). These assumptions allow the rate of superoxide production by a particular donor to be calibrated to the reduction state of the appropriate reporter. In the present study we calibrated the rate of superoxide production from site IF to the reduction state of NAD(P)H, and the rate of superoxide production from site IIIQo to the reduction state of cytochrome b566. (b) Reactions of donor (FMNH2) and reporter (NADH2) at site IF. (c) Reactions of donor (QH·) and reporter (reduced cytochrome b566) at site IIIQo.

Candidate sites of native superoxide and H2O2 production

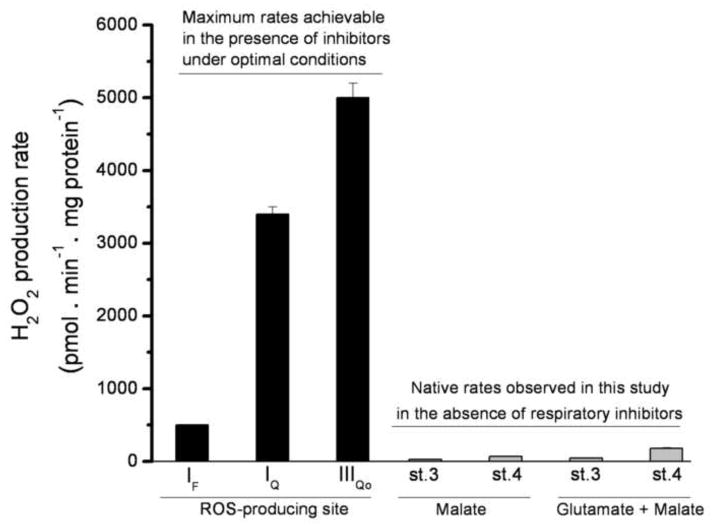

In this paper we use the term “native rate” to mean the rate in the absence of added respiratory chain inhibitors. The obvious candidates for sites of native mitochondrial superoxide and H2O2 production during oxidation of NAD-linked substrates are respiratory chain complexes I and III [12;16;29;31;32]. These two complexes contain three potentially important sites: site IF [21;31], site IQ [33;34]; and site IIIQo [12;20]. The black bars in Fig. 3 show the maximum rate of H2O2 production observed from each of these sites under optimal conditions of electron supply, in the presence of appropriate inhibitors to prevent escape of electrons, with suppression of matrix peroxidase-catalyzed losses of hydrogen peroxide.

FIGURE 3. Maximum observed rates of H2O2 production from different sites compared to the native rates observed in this study.

Black bars indicate the approximate maximum rates of H2O2 production from different sites in CDNB-treated rat skeletal muscle mitochondria, to establish a basis for comparison with the native rates. Data were obtained in standard KCl buffer (see MATERIALS AND METHODS), but lacking phosphate and magnesium (phosphate lowers the rate of H2O2 production from both site IQ and site IIIQo). Site IF was assayed in the presence of 5 mM malate, 4 μM rotenone, and 4 μM FCCP. Site IQ was assayed in the presence of 5 mM succinate as the rotenone-sensitive portion of the signal (no correction was made for the changes in rate of H2O2 production by other sites on addition of rotenone). Site IQ data were adapted from [21]. Site IIIQo was assayed with 5 mM succinate and 2.5 mM malonate, in the presence of 2 μM antimycin A, as the myxothiazol-sensitive portion of the signal (no correction was made for the changes in rate of H2O2 production by other sites on addition of myxothiazol). Site IIIQo data were adapted from [20]. The final four bars (grey) show the current assay conditions (data from Fig. 8): CDNB-treated mitochondria oxidizing 5 mM malate or 5 mM glutamate plus 5 mM malate in the absence of inhibitors during ATP synthesis (st. 3) or in non-phosphorylating conditions (st. 4); the sites generating H2O2 in each condition will be determined in this study (Fig. 8). Data are means ± SEM (n = 4).

The grey bars of Fig. 3 show the observed native rates of H2O2 production by mitochondria oxidizing NAD-linked substrates in the presence and absence of ATP synthesis. The maximum rate of H2O2 production from each site greatly exceeds any of the observed native rates, and the sum of the maximum rates is 50-fold greater than any of the native rates, illustrating vividly that any one site, or any combination of the sites, could, in principle, account for the native rates. In the following sections we will dissect the native H2O2 production under each condition into its components using reporter-based assays.

This study can be divided into two parts: (A) identification and calibration of endogenous reporters using respiratory inhibitors to define the individual sites, and (B) measurement of the reporters in a complex system in which the sites of superoxide production are unknown, prediction of the contributions of each of the reported sites, and comparison of the sum of predicted rates to the total observed native H2O2 production rates.

Experimentally, both parts of this study were performed in the same way (Fig. 4). For each condition, during either calibration or measurement, we measured Amplex UltraRed oxidation to determine the H2O2 production rate (Fig. 4a), and the redox states of two endogenous reporters, NAD(P)H (Fig. 4b) and cytochrome b566 (Fig. 4c).

The reduction state of NAD(P)H as a site-specific endogenous reporter of superoxide production at site IF

The immediate electron donor to oxygen during superoxide production at site IF (the flavin mononucleotide in the NADH oxidation site of complex I) is thought to be the fully-reduced flavin [21]. Although the reduction state of the flavin can be detected by its absorbance [35], and the “semiflavin” product can be detected using EPR [36], the signals are small and therefore unsuitable for routine use as reporters of the rate of superoxide production from site IF.

NADH, the reductant of the flavin, is more suitable as a reporter. The observation in isolated mitochondria that complex I is readily reduced by NADH, and in turn can readily reduce NAD+ during reverse electron transport, indicates that NADH and flavin may be close to equilibrium [37]. A potential problem is that NAD+ competes with NADH for the binding site, which can kinetically limit the reduction of the flavin and make it sensitive to NAD-pool size [21]. However, in isolated mitochondria the NAD-pool size is effectively constant, and any kinetic limitation by NAD+ does not appear to prevent easy reversibility. NADH may therefore be a suitable endogenous reporter of the redox state of the flavin and of IF superoxide production [26;38]. The reduction state of endogenous mitochondrial NAD(P)H can be measured by autofluorescence with excitation at 365 nm and emission at 450 nm. It is generally referred to as NAD(P)H to acknowledge that some of the signal comes from NADPH, although that contribution is expected to be small in skeletal muscle mitochondria [26]. Much of the fluorescence signal may come from NADH bound to the active site of complex I [39], making it particularly specific and suitable as an endogenous reporter of site IF. Following these considerations, we have previously found that the autofluorescence of NAD(P)H can report the rate of superoxide production at site IF under different conditions [26;38].

Calibration of NAD(P)H redox state as a reporter of superoxide production from site IF

Site IF generates superoxide at maximal rate when the NAD(P)H pool is highly reduced; this can be achieved by the addition NADH to complex I, or NAD-linked substrates to isolated mitochondria, in the presence of rotenone (a Q-binding site inhibitor of complex I) to block electron escape from the complex [26;40–42].

The site can be titrated by adding different sub-maximal concentrations of substrate. We chose to calibrate with different concentrations of malate in the presence of rotenone. This was to minimize contributions from downstream electron transport chain complexes, which will remain oxidized under these conditions. The matrix enzymes α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase can generate superoxide/H2O2 under some conditions [23–25]. If these matrix dehydrogenases do cause any H2O2 production in these calibrations with no obvious source of α-ketoglutarate or pyruvate, using electrons from NAD(P)H, it will be correctly accounted for but wrongly attributed to site IF.

Fig. 5a shows the relationship of superoxide production rate from site IF (measured as H2O2) to the concentration of malate during titration with malate in the presence of rotenone. Fig. 5b shows the relationship of NAD(P)H reduction state to the concentration of malate during parallel titrations. Fig. 5c is the replot of superoxide production rate from site IF as a function of NAD(P)H reduction in control mitochondria (filled symbols). This is the critical calibration curve to be used to report the rate of superoxide production from site IF.

For completeness, Fig. 5c also shows the relationship between superoxide production rate from site IF and NAD(P)H reduction in CDNB-treated mitochondria (open symbols). CDNB treatment, by decreasing matrix glutathione concentration and slowing matrix peroxidase-dependent consumption of H2O2, allows a more realistic approximation of actual rates of superoxide production by site IF compared to the measurements under standard conditions [26].

The reduction state of cytochrome b566 as a site-specific endogenous reporter of superoxide production at site IIIQo

The immediate electron donor to oxygen during superoxide production at site IIIQo (the quinol oxidation site located on the outer side of complex III, facing the intermembrane space) is thought to be the semiquinone in the Qo site [12;43;44]. Although this semiquinone can be detected using EPR [45], the signal is very difficult to work with and therefore unsuitable for routine use as a reporter of the rate of superoxide production from site IIIQo.

Cytochrome b566 is the immediate oxidant of this semiquinone in the Qo site [46;47], and may be more suitable as a reporter, since its reduction state can be measured by dual-wavelength absorbance spectroscopy [20;43].

In the presence of the Qi site inhibitor, antimycin A, superoxide production at site IIIQo is not a unique function of cytochrome b566 redox state but depends on the redox states of both cytochrome b566 and cytochrome b562 [20]. However, the redox relationship between these cytochromes depends on the membrane potential. At a protonmotive force of about 140 mV (applied by ATP hydrolysis) in the presence of antimycin A, cytochrome b562 has a similar apparent mid-point potential to cytochrome b566, and the dependence of superoxide production rate approximates to a function of cytochrome b566 reduction alone [20]. In the present study all measurements of native rates were made in the absence of antimycin A and the presence of high protonmotive force (140 – 183 mV). Under these conditions, the relationship between the superoxide production rate at site IIIQo and the reduction state of cytochrome b566 (Fig. 7c) was similar to that found previously when a protonmotive force of 140 mV was imposed in the presence of antimycin A [20]. Therefore, as proton motive force rises higher than 140 mV, we assume that further oxidation of cytochrome b562 relative to cytochrome b566 has no effect on the relationship between superoxide production and cytochrome b566 redox state. These considerations allow the use of cytochrome b566 redox state as a reporter of site IIIQo.

Calibration of cytochrome b566 redox state as a reporter of superoxide production from site IIIQo

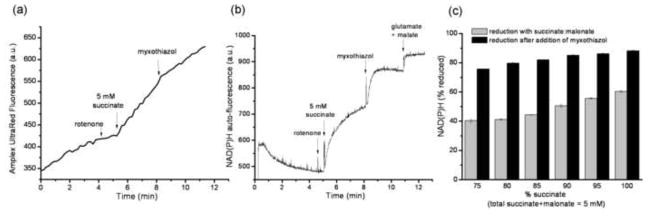

The superoxide production rate of site IIIQo was assayed as the rate with succinate as substrate, in the presence of rotenone, that was sensitive to the Qo site inhibitor myxothiazol (Fig. 6a). We initially assumed that this protocol would avoid reduction of NADH, but found that NAD(P)H was significantly reduced by succinate, and further reduced when myxothiazol was added (Fig. 6b). The residual rate of superoxide production after addition of myxothiazol in Fig. 6a was correctly reported by the IF calibration in Fig. 5c (not shown), identifying its source as site IF.

FIGURE 6. Contribution of site IF during calibration of site IIIQo.

For the calibration curve in Fig. 7c, the rate of superoxide production by site IIIQo was measured as myxothiazol-sensitive H2O2 production at different succinate:malonate ratios in the presence of rotenone. (a) Typical Amplex UltraRed fluorescence trace. 2 μM myxothiazol was added where indicated. (b) Corresponding NAD(P)H autofluorescence trace indicating that NAD(P)H becomes reduced under these conditions (5 mM glutamate plus 5 mM malate were added at the end to establish 100% reduction of the NAD(P)H pool. Therefore, correction for the changes in superoxide production from site IF before and after addition of myxothiazol was required. (c) The mean ± SEM reduction state of NAD(P)H at each succinate:malonate ratio in the absence and presence of 2 μM myxothiazol used to generate the correction using the IF calibration curve in Fig. 5c (n = 3).

The superoxide production rate of site IIIQo was calibrated at different succinate:malonate ratios. Fig. 6c shows the reduction of NAD(P)H at each succinate:malonate ratio. During reporter calibration, the contribution of site IF to the signal before and after addition of myxothiazol was corrected for during calculation of the rate from site IIIQo.

Fig. 7a shows the relationship of the superoxide production rate from site IIIQo (measured as H2O2) to the concentration of succinate during titration with different succinate:malonate ratios. Fig. 7b shows the relationship of cytochrome b566 reduction state to the concentration of succinate during parallel titrations. Fig. 7c is the replot of the corrected superoxide production rate from site IIIQo as a function of cytochrome b566 reduction in control mitochondria (filled symbols). This is the critical calibration curve to be used to report the rate of superoxide production from site IIIQo.

For completeness, Fig. 7c also shows the relationship between superoxide production rate from site IIIQo and cytochrome b566 reduction that would be predicted in CDNB-treated mitochondria (open symbols) to allow a more realistic approximation of total superoxide production by site IIIQo. The prediction was made by correcting the observed rates in control mitochondria to the rates in CDNB-treated mitochondria using the relationship in Fig. 1, assuming that 50% of the superoxide from site IIIQo is generated in the matrix [26;29;48;49].

Use of the reporters to predict native rates of mitochondrial superoxide production

The calibration curves shown in Figs 5 and 7 were constructed to report the rates of superoxide production from site IF and site IIIQo under different applied conditions in these isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria. The applied conditions could include different substrates, different inhibitors, and different respiratory states, making these reporter-based assays powerful and general tools for the characterization of mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 production. For the initial application and validation of the method, we chose to measure the native rates of superoxide production by sites IF and IIIQo in a relatively simple system: mitochondria oxidizing NAD-linked substrates (5 mM malate, or the combination of 5 mM malate plus 5 mM glutamate), in the absence of inhibitors, during maximum rates of ATP synthesis (phosphorylating; state 3), or in the presence of oligomycin to establish non-phosphorylating conditions (state 4).

For these experiments, NAD(P)H reduction state, cytochrome b566 reduction state, and the overall rate of H2O2 production were measured in parallel on the same batch of skeletal muscle mitochondria (in different cuvettes), as exemplified in Fig. 4. The observed reduction levels of the two reporters are listed in Table 1. These values were used to report the rates of superoxide generation from sites IF and IIIQo using the calibration curves in Fig. 5c and Fig. 7c. The predicted rates of superoxide production from each site for control and CDNB-treated mitochondria are reported in Table 2 and Fig. 8. The measured total rates of H2O2 production under the same conditions are also shown, allowing comparison of the sum of the reported rates from each site with the experimentally-observed total rates.

TABLE 2.

Reported and measured native rates of superoxide and H2O2 production by mitochondria oxidizing NAD-linked substrates in the absence of electron transport chain inhibitors. Reported rates were calculated from the data in Table 1 using the calibration curves for control or CDNB-treated mitochondria as appropriate in Fig. 5c for site IF and Fig. 7c for site IIIQo. Measured rates refer to control or CDNB-treated mitochondria as shown.

| Rate of superoxide or H2O2 production (pmol H2O2·min−1·mg protein−1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated rate from site IF | Estimated rate from site IIIQo | Sum of estimated rates | Total measured rate | |||||

| Control | CDNB | Control | CDNB | Control | CDNB | Control | CDNB | |

| 5 mM malate, phosphorylating | 12 ± 1 | 22 ± 2 | 3 ± 5 | 4 ± 8 | 15 ± 5 | 26 ± 8 | 16± 2 | 26±2 |

| 5 mM malate, non-phosphorylating | 13 ± 1 | 25 ± 2 | 9 ± 6 | 14 ± 9 | 21 ± 6 | 39 ± 9 | 39**±2 | 69*±1 |

| 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate, phosphorylating | 12 ± 1 | 23 ± 2 | 5 ± 5 | 9 ± 8 | 18 ± 5 | 32 ± 8 | 29 ±1 | 47 ±4 |

| 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate, non-phosphorylating | 40 ± 6 | 83 ± 11 | 26 ± 9 | 40 ± 14 | 66 ± 11 | 123 ± 17 | 108***±5 | 182**±9 |

Values are means ± SEM, n = 6 for control conditions, and n = 4 for CDNB. SEM values for reported rates were determined by error propagation and significance was tested using Welch’s t-test, see MATERIALS AND METHODS.

p<0.05,

p<0.02,

p<0.01 compared to the appropriate sum of reported rates.

The results for the four experimental conditions are shown in Fig. 8. Figs 8a and 8b show H2O2 production by mitochondria oxidizing malate; Figs 8c and 8d show production by mitochondria oxidizing glutamate plus malate.

When mitochondria oxidized malate whilst generating ATP (Fig. 8a), NAD(P)H and cytochrome b566 were relatively oxidized (Table 1), as would be expected since malate is a relatively poor substrate for supply of electrons, and ATP synthesis keeps the protonmotive force relatively low (140 mV) and the electron transport chain relatively oxidized. Under these conditions, the reported rates of superoxide production were low (Table 2, Fig. 8a). Most of the superoxide (~80%) was reported to arise from site IF. The sum of the reported rates was not different from the measured rate of H2O2 production (second bar in Fig. 8a) (p>0.8; t-test). This good agreement between the sum of the reported rates and the measured rate is consistent with the reporters working well, and with little or no contribution to H2O2 production under these conditions from sites other than IF and IIIQo. The third bar in Fig. 8a shows the rates reported using the CDNB-corrected calibration curves in Figs 5c and 7c. Because the correction was applied to the whole of the superoxide production from site IF, but only to the 50% of superoxide production from site IIIQo assumed to be in the matrix, and because the correction is different at different rates, the proportion of superoxide production reported from site IF was slightly changed. Again, there was good agreement between the sum of the reported rates and the measured H2O2 production rate (fourth bar in Fig. 8a); there was no statistical difference between the total reported and measured H2O2 production rates (p>0.9; t-test).

Fig. 8b shows the same analysis, but this time of mitochondria oxidizing malate under non-phosphorylating conditions (not generating ATP), in which the protonmotive force was higher (165 mV) and the electron transport chain was consequently less oxidized (Table 1). The reported contribution of site IF was little changed, but the reported contribution of site IIIQo increased ~3-fold (Table 2). The reported superoxide production rate was shared between sites IF and IIIQo (~36% IF and ~20% IIIQo). In this case the sum of the reported rates was significantly less than the measured H2O2 production rate. In the CDNB treated mitochondria, the reporters accounted for only about half of the observed rate, with ~30 pmol H2O2 • min−1 • mg protein−1 remaining unassigned to either site.

Figs 8c and 8d show the second experimental condition, mitochondria oxidizing glutamate and malate. Addition of glutamate removes matrix oxaloacetate by transamination and makes malate a more effective substrate for supply of electrons. Fig. 8c shows the phosphorylating state. Compared to Fig. 8a, addition of glutamate increased protonmotive force from 140 to 158 mV, appeared to cause slightly more reduction of cytochrome b566, but not of NAD(P)H, and increased the reported contribution of IIIQo, but not of site IF (Table 2). The reported and measured rates in CDNB-treated mitochondria are also shown. Both sites IF and IIIQo contributed to superoxide production, with site IF tending to dominate (~70% IF). There was no significant difference between the sum of the reported rates and the observed rate of H2O2 production in either set of data.

Fig. 8d shows the analysis of H2O2 production by mitochondria oxidizing glutamate plus malate, but under non-phosphorylating conditions. These conditions generated the highest rates of H2O2 production observed in this study. Because of the good electron supply and high protonmotive force (183 mV), there was relatively high reduction of both NAD(P)H and cytochrome b566 (Table 1). This led to relatively high reported rates from both sites. Compared to the phosphorylating state, the rate of superoxide production by site IIIQo increased ~4–5-fold (Table 2). The reported rate of superoxide production was shared between sites IF and IIIQo (~45% IF and ~22% IIIQo). Similarly to the situation with malate in the non-phosphorylating condition, the sum of the reported rates was significantly less than the observed H2O2 production rate. In the CDNB-treated mitochondria ~60 pmol H2O2 • min−1 • mg protein−1 were unassigned, accounting for ~33% of the observed signal.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study is the first to dissect the individual sites of superoxide production by mitochondria under native conditions of oxidation of NAD-linked substrates with no added respiratory chain inhibitors.

The two conditions that most favour formation of H2O2 by isolated mitochondria are a highly reduced NAD(P)H pool [21;26;50], and a high protonmotive force together with a reduced ubiquinone pool [33;38;51;52]. From studies using respiratory chain inhibitors, we know which sites are most active under specific contrived conditions, such as site IQ during oxidation of succinate before addition of rotenone [33;51;52], site IF during oxidation of NAD-linked substrates in the presence of rotenone [40–42], or site IIIQo during oxidation of succinate in the presence of rotenone and antimycin A [12;20;43;44]. Although efforts have been made to characterize the mitochondrial sites that generate superoxide/H2O2 in complex systems [53–56], such studies using inhibitors do not unambiguously reveal which sites are most active under native conditions in the absence of added respiratory chain inhibitors with more physiologically-relevant substrates.

Previous studies that have attempted to identify specific sites used pharmacological or genetic manipulation of putative sites of superoxide/H2O2 production and inferred the sites from the resulting changes in ROS production. For example, it is sometimes reported that addition of antimycin A to cells increases ROS production, with the implied or explicit inference that the native ROS production must have been from complex III (e.g. [57]). This inference is invalid for two reasons. First, the observation that a site produces ROS after inhibition does not show that it produced them before the addition of the inhibitor. Second, the addition of an inhibitor will increase superoxide/H2O2 production from upstream sites as they become more reduced, and decrease superoxide/H2O2 production from any downstream sites as they become more oxidized, distorting the pattern of production so much that few valid inferences can be made about the native sites of production before inhibitor addition. Similarly, addition of inhibitors of site IIIQo, such as myxothiaxol or stigmatellin, or genetic ablation of IIIQo activity [58] may decrease ROS production in cells. However, such inhibition will tend to increase superoxide/H2O2 production from site IF and complex II by causing reduction of ubiquinone and NADH, and to decrease production from site IQ by lowering the protonmotive force. These complications make the assignment of production to site IIIQo using these methods unreliable.

Previous studies recognized that the reduction states of the NADH and ubiquinone pools affect or determine superoxide production rates, but did not calibrate these relationships or use them for quantitative predictions. Such studies related the observed rate of superoxide production by site IF to NAD(P)H reduction state [21;31;38], and the observed rate of superoxide production by site IIIQo to cytochrome b566 reduction state [20].

In the present paper we introduce a novel general solution to the problem of identifying and quantifying individual sites of superoxide/H2O2 production: the calibration of endogenous reporters using inhibitors to define the sites that they report on, and the measurement of those reporters in the absence of added respiratory chain inhibitors to predict native rates of superoxide production from individual sites and their contribution to the total rate of superoxide production. We show that NAD(P)H reduction state can be used to report the rate of superoxide production from site IF, and cytochrome b566 reduction state can be used to report the superoxide production rate from site IIIQo. Using these calibrated reporters, we estimated the contributions of sites IF and IIIQo to H2O2 production in mitochondria isolated from rat skeletal muscle oxidizing malate or glutamate plus malate as substrates under two different conditions.

Fig. 8 shows that under phosphorylating conditions the reported rates of superoxide production from sites IF and IIIQo accounted fully for the observed rates, with site IF generating much of the total. We conclude that these two sites are the only significant contributors to mitochondrial H2O2 production during ATP synthesis under the conditions used in the present paper.

Under non-phosphorylating conditions superoxide production was ~40% from site IF, ~20% from site IIIQo and ~40% from unidentified sites. It is possible that this difference between reported and observed rates reflects systematic errors in our assumptions and calibrations, or it may suggest that there were contributions to H2O2 production by other sites in this system. The best candidates for other site(s) are the lipoic acid-containing enzyme complexes (α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase) and site IQ. Complex II is not a good candidate, since its superoxide/H2O2 production is strongly inhibited by malate [18], which was added in all the current experiments.

When malate alone is oxidized, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase is not expected to be active. However, in the presence of glutamate it is possible that α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase was provided sufficient substrate to generate superoxide/H2O2 [23–25], and this could have contributed some of the unassigned H2O2 generation during oxidation of glutamate plus malate. However, when we used 5 mM glutamate plus 5 mM malate instead of 5 mM malate alone in the IF calibration of Fig. 5c (data not shown) there was no significant difference in the rate of H2O2 production. This suggests that α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase does not contribute significant H2O2 to the total even when glutamate is present under our conditions.

Site IQ generates superoxide/H2O2 at high rates in the presence of succinate and absence of rotenone [33] (Fig. 3), and in the presence of rotenone and NAD-linked substrates when a protonmotive force is generated by ATP hydrolysis [54]. The site is very sensitive to protonmotive force (particularly the transmembrane pH gradient) [33] and to the redox state of the ubiquinone pool [38], both of which increase under non-phosphorylating compared to phosphorylating conditions, and during oxidation of glutamate plus malate compared to malate alone. Therefore, site IQ is an attractive candidate for the unassigned H2O2 production during non-phosphorylating respiration with malate alone and with glutamate plus malate as substrates.

Our results show that the rate of H2O2 production by mitochondria depends strongly on their state (i.e. on the protonmotive force): in mitochondria treated with CDNB the rate of H2O2 production increased 2–3-fold (malate) or ~4-fold (glutamate plus malate) between the phosphorylating and non-phosphorylating states (Table 2). The rate of superoxide/H2O2 production by the electron transport chain cannot depend simply on the rate of electron flow through the chain (as implied when rates are reported as a percentage of respiration rate), since there is no obvious mechanism for such a relationship, and rates are increased when electron transport is stimulated by addition of substrate, yet decreased when electron transport is increased by addition of uncouplers [28]. However, in this context in which no inhibitors were added and respiration was not manipulated, reporting ROS production as a percentage of respiration can give a general sense of the scale of the electron leak. In non-phosphorylating conditions, electron leak to oxygen was 0.25% (malate) and 0.4% (glutamate plus malate) of total respiration rate. Under phosphorylating conditions it was considerably less, 0.03% (malate) and 0.02% (glutamate plus malate) of total respiration rate.

An interesting aspect of our results is the prediction that the rate of direct superoxide production (as opposed to H2O2 production) in the extramitochondrial compartment depends even more strongly on the respiratory state of the mitochondria: the rate of external superoxide production increased ~3-fold (malate) or 4–5-fold (glutamate plus malate) between phosphorylating and non-phosphorylating states (Table 2). External superoxide production is expected to arise only from site IIIQo in this system. Superoxide from site IF, site IQ and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase is produced exclusively in the matrix [29], but ~50% of site IIIQo superoxide production is thought to be directed to the extramitochondrial compartment [26;29;48;49]. In principle, these large changes in extramitochondrial H2O2 or superoxide production rate could be used to signal the respiratory state of the mitochondria to the cytosolic compartment through H2O2 or superoxide-sensitive components in the cytosol, as proposed by others [16;17;58].

As a proof of concept and illustration of its application, the experimental design in the present work was necessarily relatively simple. However, the method can readily be expanded to other substrates, conditions, and sites of interest. For example, site IQ has one of the highest measured Vmax values of all the mitochondrial H2O2-producing sites [17;33], (Fig. 3), but its contribution to H2O2 production during oxidation of physiologically-relevant substrates such as fatty acids or glycerol 3-phosphate in cells, or in vivo is unknown. Similarly, complex II, α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, ETFQOR and lipoic acid containing dehydrogenases may each be capable of generating superoxide/H2O2 at significant rates under specific conditions. Through careful experimental design, the strategy introduced here should enable elucidation of the specific H2O2-producing behaviour of isolated mitochondria under many experimental conditions. If technical issues can be resolved, extension of these principles may also prove useful with intact cells as well as whole tissues and organisms. An improved understanding of which mitochondrial superoxide-and H2O2-producing sites are active physiologically and pathologically should greatly assist evaluation of the mechanisms and roles of mitochondrial ROS production in physiology and pathology.

Highlights.

Redox state of endogenous reporters was calibrated to rates of H2O2/O2/·− production

NADH and cytochrome b reported H2O2/O2/·− production from complexes I and III

Site-specific rates of H2O2/O2·− production were quantified under native conditions

This approach can quantify site-specific H2O2/O2/·− production in complex situations

Acknowledgments

FUNDING This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 AG025901, PL1 AG032118 and R01 AG033542 and by The Ellison Medical Foundation, grant AG-SS-2288-09. JRT is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

We thank Akos A. Gerencser for contributing his expertise in mathematical analysis.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ROS, reactive oxygen species; CDNB, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene; IF, flavin site of complex I; IQ, quinone-binding site of complex I; IIIQo or Qo, quinol oxidation site of complex III; IIIQi or Qi, quinone reduction site of complex III; SOD, superoxide dismutase; FCCP, carbonylcyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Begriche K, Igoudjil A, Pessayre D, Fromenty B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH: causes, consequences and possible means to prevent it. Mitochondrion. 2006;6:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green K, Brand MD, Murphy MP. Prevention of mitochondrial oxidative damage as a therapeutic strategy in diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 1):S110–S118. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witte ME, Geurts JJG, de Vries HE, van der Valk P, van Horssen J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: a potential link between neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Mitochondrion. 2010;10:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Neuzil J, Saavedra E, Moreno-Sanchez R. The causes of cancer revisited: “mitochondrial malignancy” and ROS-induced oncogenic transformation - why mitochondria are targets for cancer therapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:145–170. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barja G. Free radicals and aging. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller FL, Lustgarten MS, Jang Y, Richardson A, Van Remmen H. Trends in oxidative aging theories. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:477–503. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladiges W, Van Remmen H, Strong R, Ikeno Y, Treuting P, Rabinovitch P, Richardson A. Lifespan extension in genetically modified mice. Aging Cell. 2009;8:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mookerjee SA, Divakaruni AS, Jastroch M, Brand MD. Mitochondrial uncoupling and lifespan. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131:463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinlan CL, Treberg JR, Brand MD. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Free Radical Production and their Relationship to the Aging Process. In: Masoro E, Austad SN, editors. The Handbook of the Biology of Aging. Academic Press; San Diego, USA: 2010. pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:7–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boveris A, Oshino N, Chance B. The cellular production of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J. 1972;128:617–630. doi: 10.1042/bj1280617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loschen G, Flohe L, Chance B. Respiratory chain linked H2O2 production in pigeon heart mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1971;18:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCord JM, Fridovich I. The biology and pathology of oxygen radicals. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:122–127. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adam-Vizi V. Production of reactive oxygen species in brain mitochondria: contribution by electron transport chain and non-electron transport chain sources. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1140–1149. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Treberg JR, Perevoshchikova IV, Brand MD. Mitochondrial complex II generates superoxide in the forward and reverse reactions. J Biol Chem. 2012 Jun 11; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374629. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Affourtit C, Quinlan CL, Brand MD. Measurement of proton leak and electron leak in isolated mitochondria. In: Palmeira CM, Moreno AJ, editors. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2012. pp. 165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinlan CL, Gerencser AA, Treberg JR, Brand MD. The mechanism of superoxide production by the antimycin-inhibited mitochondrial Q-cycle. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:31361–31372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J, Trumpower BL. Superoxide anion generation by the cytochrome bc1 complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;419:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kussmaul L, Hirst J. The mechanism of superoxide production by NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7607–7612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510977103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunik VI, Sievers C. Inactivation of the 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase complexes upon generation of intrinsic radical species. Eur J Biochem. 2002:5004–5015. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starkov AA, Fiskum G, Chinopoulos C, Lorenzo BJ, Browne SE, Patel MS, Beal MF. Mitochondrial alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex generates reactive oxygen species. JNeurosci. 2004;24:7779–7788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Reaction Catalyzed by alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7771–7778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1842-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treberg JR, Quinlan CL, Brand MD. Hydrogen peroxide efflux from muscle mitochondria underestimates matrix superoxide production - a correction using glutathione depletion. FEBS J. 2010;277:2766–2778. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meinhardt SW, Crofts AR. The role of cytochrome b566 in the electron-transfer chain of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. Biochim Biophys Acta, Bioenerg. 1983;723:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(83)90120-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brand MD, Affourtit C, Esteves TC, Green K, Lambert AJ, Miwa S, Pakay JL, Parker N. Mitochondrial superoxide: production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:755–767. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St-Pierre J, Buckingham JA, Roebuck SJ, Brand MD. Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44784–44790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman DL, Brookes PS. Oxygen sensitivity of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation depends on metabolic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16236–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809512200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansford RG, Hogue BA, Mildaziene V. Dependence of H2O2 formation by rat heart mitochondria on substrate availability and donor age. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997;29:89–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1022420007908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Fiskum G, Schubert D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Neurochem. 2002;80:780–787. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambert AJ, Brand MD. Superoxide production by NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) depends on the pH gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Biochem J. 2004;382:511–517. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treberg JR, Brand MD. A model of the proton translocation mechanism of complex I. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17579–17584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholz R, Thurman RG, Williamson JR, Chance B, Bücher T. Flavin and pyridine nucleotide oxidation-reduction changes in perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:2317–2324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohnishi ST, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Ohta K, Yoshikawa S, Ohnishi T. New insights into the superoxide generation sites in bovine heart NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I): The significance of protein-associated ubiquinone and the dynamic shifting of generation sites between semiflavin and semiquinone radicals. Biochim Biophys Acta, Bioenerg. 2010;1797:1901–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown GC, Brand MD. Proton/electron stoichiometry of mitochondrial complex I estimated from the equilibrium thermodynamic force ratio. Biochem J. 1988;252:473–479. doi: 10.1042/bj2520473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treberg JR, Quinlan CL, Brand MD. Evidence for two sites of superoxide production by mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27103–27110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.252502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blinova K, Levine RL, Boja ES, Griffiths GL, Shi-Zhen D, Ruddy B, Balaban RS. Mitochondrial NADH Fluorescence Is Enhanced by Complex I Binding. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9636–9645. doi: 10.1021/bi800307y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrero A, Barja G. Sites and mechanisms responsible for the low rate of free radical production of heart mitochondria in the long-lived pigeon. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;98:95–111. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(97)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirst J, King MS, Pryde KR. The production of reactive oxygen species by complex I. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:976–980. doi: 10.1042/BST0360976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fato R, Bergamini C, Bortolus M, Maniero AL, Leoni S, Ohnishi T, Lenaz G. Differential effects of mitochondrial Complex I inhibitors on production of reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta, Bioenerg. 2009;1787:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erecinska M, Chance B, Wilson DF, Dutton PL. Aerobic reduction of cytochrome b 566 in pigeon-heart mitochondria (succinate-cytochrome C1 reductase-stopped-flow kinetics) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:50–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muller F, Crofts AR, Kramer DM. Multiple Q-cycle bypass reactions at the Qo site of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7866–7874. doi: 10.1021/bi025581e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cape JL, Bowman MK, Kramer DM. A semiquinone intermediate generated at the Qo site of the cytochrome bc1 complex: Importance for the Q-cycle and superoxide production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7887–7892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702621104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trumpower BL. Evidence for a protonmotive Q cycle mechanism of electron transfer through the cytochrome b–c1 complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;70:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)91110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crofts AR. The cytochrome bc1 complex: function in the context of structure. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:689–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.150251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller FL, Liu Y, Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49064–49073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miwa S, Brand MD. The topology of superoxide production by complex III and glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase in Drosophila mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2005;1709:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kudin AP, Bimpong-Buta NY, Vielhaber S, Elger CE, Kunz WS. Characterization of superoxide-producing sites in isolated brain mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4127–4135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korshunov SS, Skulachev VP, Starkov AA. High protonic potential actuates a mechanism of production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1997;416:15–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller FL, Liu Y, Abdul-Ghani MA, Lustgarten MS, Bhattacharya A, Jang YC, Van Remmen H. High rates of superoxide production in skeletal-muscle mitochondria respiring on both complex I- and complex II-linked substrates. Biochem J. 2008;409:491–499. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turrens JF, Alexandre A, Lehninger AL. Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:408–414. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lambert AJ, Brand MD. Inhibitors of the quinone-binding site allow rapid superoxide production from mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39414–39420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gyulkhandanyan AV, Pennefather PS. Shift in the localization of sites of hydrogen peroxide production in brain mitochondria by mitochondrial stress. J Neurochem. 2004;90:405–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kudin AP, Malinska D, Kunz WS. Sites of generation of reactive oxygen species in homogenates of brain tissue determined with the use of respiratory substrates and inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2008;1777:689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klimova T, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial complex III regulates hypoxic activation of HIF. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:660–666. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Moraes CT, Murphy MP, Budinger GRS, Chandel NS. The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:1029–1036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]