Abstract

Retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) and retinitis pigmentosa (RP) affect millions of people. Replacing lost cells with new cells that connect with the still functional part of the host retina might repair a degenerating retina and restore eyesight to an unknown extent. A unique model, subretinal transplantation of freshly dissected sheets of fetal-derived retinal progenitor cells, combined with its retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), has demonstrated successful results in both animals and humans. Most other approaches are restricted to rescue endogenous retinal cells of the recipient in earlier disease stages by a ‘nursing’ role of the implanted cells and are not aimed at neural retinal cell replacement. Sheet transplants restore lost visual responses in several retinal degeneration models in the superior colliculus (SC) corresponding to the location of the transplant in the retina. They do not simply preserve visual performance – they increase visual responsiveness to light. Restoration of visual responses in the SC can be directly traced to neural cells in the transplant, demonstrating that synaptic connections between transplant and host contribute to the visual improvement. Transplant processes invade the inner plexiform layer of the host retina and form synapses with presumable host cells. In a Phase II trial of RP and ARMD patients, transplants of retina together with its RPE improved visual acuity.

In summary, retinal progenitor sheet transplantation provides an excellent model to answer questions about how to repair and restore function of a degenerating retina. Supply of fetal donor tissue will always be limited but the model can set a standard and provide an informative base for optimal cell replacement therapies such as embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived therapy.

Keywords: retinal degeneration, retinal transplantation, retinal progenitor sheets, electrophysiology, superior colliculus, trans-synaptic tracing, electron microscopy

1. Introduction: Cell replacement therapies for retinal degeneration

The transplanting of immature, freshly harvested retina together with or without its RPE as a sheet is currently the method that can lead to fully developed functional photoreceptors in severely degenerated recipients that have lost most photoreceptors at the time of transplantation. Since our previously published reviews in this journal (Aramant and Seiler, 2002a; Aramant and Seiler, 2004), much progress has been made toward demonstrating the mechanism of visual restoration by retinal sheet transplants.

The purpose of this article is to describe the positive results of fetal sheet transplantation compared to other cell transplantation approaches, with a special emphasis on the evidence of functional connectivity and long-term retinal restoration. We define “restoration” either as a morphological repair of a retinal area with lamination resembling normal retina, or as a stable improvement of visual function compared to the stage of retinal degeneration of the host at time of surgery. It does not mean to have reached a level of vision of a normal retina. “Rescue” means preservation of remaining photoreceptors so that there is better visual function at a later time compared to the corresponding untreated stage of retinal degeneration.

1.1 Short overview of retinal degenerative diseases

Retinal degenerative diseases first induce destruction of photoreceptors or RPE, and then affect the nearest inner retinal cell layers. These cells can look histologically normal but have started the disease process (review: Marc, 2010). Diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) or retinitis pigmentosa (RP) affect millions of people and lead to irreversible vision loss. In ARMD, loss of vision occurs in the central retina first; in RP, peripheral vision is lost first. In spite of the synaptic rewiring (“remodeling”) that occurs after loss of photoreceptors and RPE (review: Jones and Marc, 2005; Marc et al., 2007), the remaining inner retinal layers maintain their thickness for a long time (Humayun et al., 1999). Retinal ganglion cells can also still produce action potentials after electrical stimulation in the absence of photoreceptor input (Margolis et al., 2008; Jensen and Rizzo, 2009; Kolomiets et al., 2010).

1.2. Retinal degeneration models

We have provided an extensive, more detailed review of retinal degeneration models in our previous reviews (Aramant and Seiler, 2002a; Aramant and Seiler, 2004). Important is to keep in mind that each retinal degeneration model has its own unique features and causes. The results achieved in one model often cannot be reproduced in another. In particular, trophic effects on photoreceptors can vary across models (see section 5.5).

1.2.1 Induced retinal degeneration models

Light damage models had been widely used before inherited retinal degeneration models became widely available. Both Silverman and Del Cerro used light damaged albino rats as recipient for retinal transplants. Rats were exposed to continuous white light for 4-5 weeks at 3500 lux (del Cerro et al., 1991) or 2-4 weeks at 1900 lux (Silverman and Hughes, 1989). In contrast, exposure to 420 nm blue light of moderate intensity (680-1290 lux) requires only 2-4 days to specifically destroy almost all photoreceptors while sparing the RPE (Seiler et al., 2000). This procedure was used in early retinal sheet transplantation studies (Seiler and Aramant, 1998). In addition, blue light damage has been used to accelerate retinal degeneration in the S334ter line 3 transgenic rat (Thomas et al., 2007). However, light damage cannot be achieved in albino rabbits (unpublished observations) possibly due to the avascular retina. Light damaged minipigs have been used for transplantation of human fetal retina/RPE sheets (Li et al., 2009). Further discussion of different light damage models can be found in other reviews (Wenzel et al., 2005; Organisciak and Vaughan, 2010).

Drugs have been used to induce retinal degeneration, such as sodium iodate (Henkind and Gartner, 1983) for destruction of RPE and MNU (N-Methyl-N-nitrosourea) for destruction of photoreceptors (review: Tsubura et al., 2011). However, if used at a dosage that is not generally toxic, this kind of drug treatment only results in patchy and incomplete damage which makes it difficult to study the functional effect of transplants.

1.2.2. Inherited and transgenic rodent retinal degeneration models

A recent review of naturally occurring models of retinal degeneration can be found in Baehr and Frederick (2009). The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rat which has a defect in RPE phagocytosis (D'Cruz et al., 2000) and the retinal degenerate (rd) 1 mouse with a defect in the β-phosphodiesterase gene (Bowes et al., 1990) have been the most commonly used models for retinal cell replacement and rescue strategies. Photoreceptors degenerate relatively slowly in the RCS rat secondarily to RPE dysfunction, whereas rd mice show loss of photoreceptors early on and never develop outer segments. Rds mice have a mutation in the rds/peripherin gene and show slow photoreceptor degeneration over several months.

With the advancement of transgenic technologies, many human mutations identified in retinal diseases have been cloned into animals, commonly mice (review: Chang et al., 2005). Fewer transgenic rat models have been created on an albino Sprague-Dawley rat background, using the P23H and S334ter mutation of rhodopsin (Steinberg et al., 1996; Pennesi et al., 2008; Martinez-Navarrete et al., 2011). For most of our latest transplantation studies, we have used transgenic pigmented S334ter line 3 rats, a model of dominant RP with fast retinal degeneration. Because there is a homozygous strain available, mating with pigmented rats results in pigmented heterozygous rats that are more useful for functional testing than albinos. The rate of retinal degeneration is not affected by the pigmentation. Eye surgery is also easier in rats than in mice. For testing of human tissue without immunosuppression, we have recently developed a pigmented immunodeficient retinal degenerate rat strain, a cross between S334ter line 3 and NIH nude rats [SD-Foxn1 Tg(S334ter)3Lav], which is now available through the Rat Research Resource Center at the University of Missouri (www.rrrc.us).

1.2.3 Large animal models of retinal degeneration

Many naturally occurring mutations that lead to retinal degeneration have been found in dogs (review: Tsai et al., 2007), and cats (review: Narfstrom et al., 2011). In addition, rhodopsin Pro347Leu-transgenic retinal degeneration models have also been created in pigs (Li et al., 1998) and rabbits (Kondo et al., 2009). The rate of retinal degeneration is, however, very slow in most larger transgenic models. Recently, a transgenic minipig has been developed that more closely mimics RP with a faster rate of degeneration (Ross et al., 2012).

1.3. Treatment strategies for retinal degeneration

Most current experimental approaches target early disease stages, with the aim of preventing degeneration of cones. Micronutrient supplements (Berson et al., 2004) and gene therapy to introduce trophic factors or to correct mutated genes (Liu et al., 2011) may help in the early stages. Many factors (e.g., basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF], ciliary derived neurotrophic factor [CNTF], pigment epithelium derived factor [PEDF], glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor [GDNF], brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF]) delay degeneration of retinal cells, and protect photoreceptors in different models of retinal degeneration (review: (LaVail, 2005). Phase II clinical trials with encapsulated RPE cells producing CNTF have shown some photoreceptor protection in ARMD and RP patients with early stages of retinal degeneration (Talcott et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; review: Wen et al., 2012). Although the effect of most factors on photoreceptor survival is indirect via microglia and Müller cells (Taylor et al., 2003), red-green cones express the BDNF receptor trkB and can directly respond to BDNF (Di Polo et al., 2000). CNTF treatment up-regulates both BDNF and bFGF in Müller cells (Harada et al., 2002). In rd mice, transplants of rods slow cone degeneration (Mohand-Said et al., 2000). This so-called rod-derived cone viability factor (RdCVF) is a diffusible factor, synthesized by rods, and distinct from known trophic factors (Leveillard et al., 2004).

In contrast, retinal sheet transplantation targets extended, especially later-stage retinal degeneration when photoreceptors and/or RPE have been irreversibly damaged. Two other treatment strategies that are targeting later disease stages are not covered in this review: development of a retinal prosthesis (reviews: Matthaei et al., 2011; Ong and Cruz, 2011) and gene transfer to make either retinal ganglion cells or bipolar cells responsive to light by introducing light-sensitive bacterial or algae proteins (Tomita et al., 2009; Busskamp and Roska, 2011).

1.4. Criteria for successful transplants

To be successful, transplants should (1) replace lost photoreceptors with new, functional and morphologically differentiated cells, (2) make appropriate synaptic connections with the host retina, and (3) restore visual function to an objectively measurable degree in the brain that can be demonstrated by different functional tests (electrophysiology, behavior, etc.). (4) In addition, transplants should not form tumors or in any other way be harmful to recipients.

2. History of retinal transplantation

This review concentrates on cellular replacement therapy, with emphasis on sheets of retina together with its RPE (Figure 1) that established proof of principle in 2001 (Woch et al., 2001). Retinal sheet transplantation is based on the hypothesis that degenerated cells can be replaced with healthy cells that can connect with the remaining inner retina. Because many patients with retinal degeneration have lost both photoreceptors and RPE, both tissues should be replaced together. Transplantation of photoreceptors can only have a limited effect when the patient needs new RPE. Or in reverse, it makes little sense of transplanting RPE when the patient has almost no photoreceptors left to be rescued.

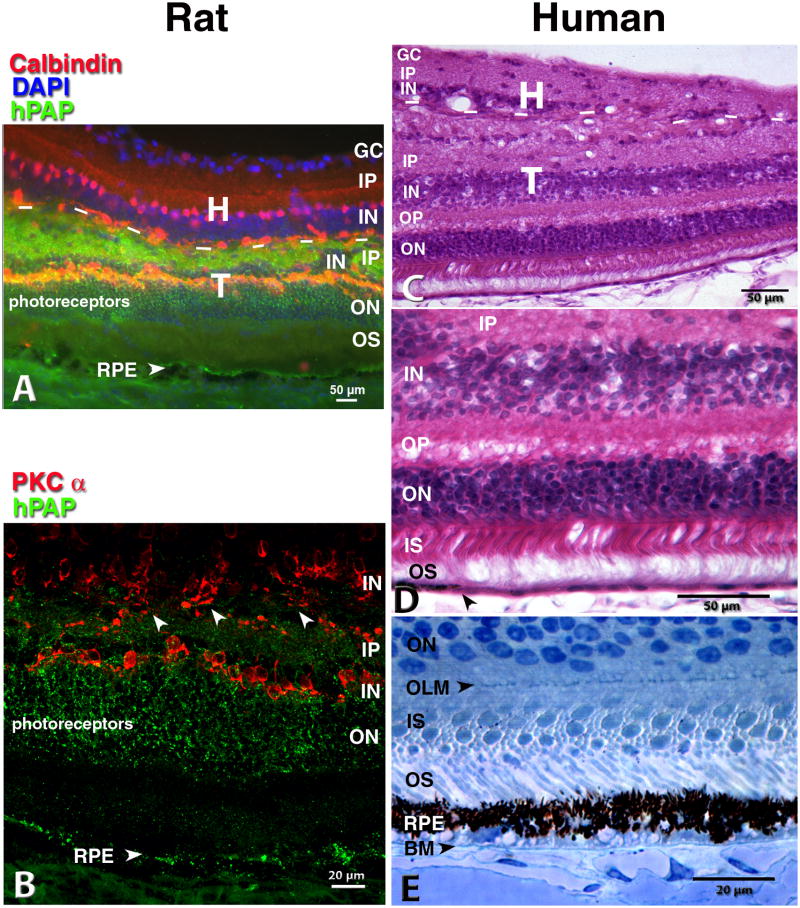

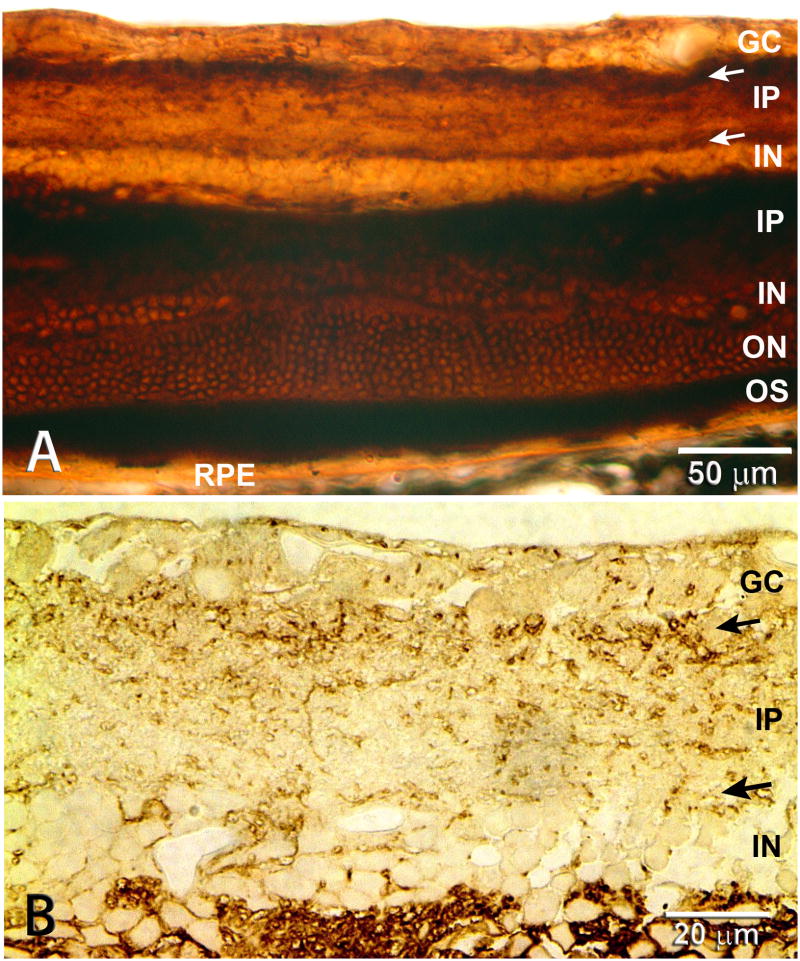

Figure 1. Rat and human retina, transplanted together with its RPE to the subretinal space.

From a sheet of neuroblastic cells, the transplant develops most retinal layers and cell types together with a monolayer of RPE seemingly in interaction with host choroid. A) B) Rat transplant to RCS rat 5.6 mo. after surgery; C) D) E) human transplant to nude rat 11.7 mo. after surgery.

(A) Double staining: Green hPAP label of all donor cells' cytoplasm, including processes, in combination with Calbindin (red) that labels horizontal and some amacrine cells. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Dashed lines: approximate border between transplant and host. Orange band of transplant horizontal cells double-stained for hPAP and Calbindin. The host horizontal cells border the transplant-host interface. The choroid shows some unspecific green autofluorescence which can be clearly distinguished from specific staining in the confocal microscope (B). (B) Single confocal scan of adjacent section: donor hPAP (green) and rod bipolar cells (PKC alpha, red). Arrow heads indicate areas with potentially crossing processes. Note the hPAP label of the co-transplanted RPE cells in A) and B). (C, D,E) Human transplant to normal albino athymic nude rats. C),D), Donor 12 weeks post-conception, 11.7 months after surgery, H-E staining. The transplant has developed all retinal layers with the exception of ganglion cells. (D) Enlargement of C). Arrow head in D) indicates transition from pigmented to non-pigmented RPE. (E) Toluidine blue-stained 1 μm semithin section. Human donor 14 weeks post-conception, 8.9 months post-surgery. Inner segments of individual transplant cones and rods clearly outlined. Normal appearing donor RPE with apical melanosomes adjacent to transplant photoreceptor outer segments. Close to the human Bruch's membrane, many rat host choroidal blood vessels can be seen. No trace of host albino rat RPE. Image in A) taken with standard Nikon FXA fluorescence microscope and deconvoluted (Autoquant, Autodeblur software 9.2 and 9.3). Scale bars: 50 μm (A,C,D), 20 μm (B,E). (A) Reprinted with permission from Seiler et al., 2008: Transplants of retinal layers– a hope to preserve and restore vision? Optonics and Photonics News, 19(4): 37-42. Copyright The Optical Society.

2.1 Transplantation of RPE and other supporting cells

RPE cells support photoreceptor function by maintaining the blood-retinal barrier, maintaining the Vitamin A cycle, providing nutrition and trophic support to the photoreceptors and phagocytosis of outer segments (Binder et al., 2007; Lee and Maclaren, 2011). The possibility of RPE transplantation was first investigated by Gouras et al. (1984). Since the demonstration that RPE cells can delay photoreceptor degeneration in RCS rats (Li and Turner, 1988; Lopez et al., 1989), this rescue effect and its functional implications have been studied extensively (Yamamoto et al., 1993; Sauvé et al., 1998; Girman et al., 2003; Gias et al., 2007), leading to clinical trials (Algvere et al., 1999) (see section 7). Because of supply issues, several laboratories have derived RPE cells from human embryonic stem cells (hESC) (Klimanskaya et al., 2004; Vugler et al., 2008a) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) (Buchholz et al., 2009; Kokkinaki et al., 2011) which have shown photoreceptor rescue in RCS rats (Lund et al., 2006; Carr et al., 2009) and in RPE65 −/− mice (Wang et al., 2010b). This research is now finally leading to clinical trials (see section 7). However, RPE transplants can only delay retinal degeneration and only have an effect as long as there are photoreceptors to rescue.

It has also been shown in the RCS rat that a trophic effect can be achieved by transplanting non-RPE cells, such as iris pigment epithelium (IPE) (Abe et al., 2000a; Schraermeyer et al., 2000), Schwann cells (Lawrence et al., 2000), bone marrow stem cells (Inoue et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2010), fetal brain-derived neural progenitors (Wang et al., 2008a) and ESC-derived neural progenitors (Schraermeyer et al., 2001).

Although dissociated RPE can delay photoreceptor degeneration in the RCS rat, they do not form a monolayer and thus do not contribute to the blood-retinal barrier. In addition, the aged Bruch's membrane in the patient's eye does not provide a good attachment substrate for RPE cells which inhibits RPE function (Gullapalli et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2007). There is also concern that dissociated cells may escape into the vitreous after transplantation and cause retinal detachment. Therefore, many laboratories have worked on culturing and transplanting RPE sheets isolated as patches (Sheng et al., 1995), embedded in gelatin (Del Priore et al., 2004) or grown as sheets on a biodegradable membrane carrier (Thumann et al., 1997; Lu et al., 1998) (review: Treharne et al., 2011) or on a parylene membrane (Zhu et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012).

2.2. Transplantation of neural retina

Retinal transplantation in mammals started with a study transplanting rat fetal retina to the anterior chamber of the pregnant mother's eye (Royo and Quay, 1959). Several decades later, retinal transplantation to the anterior chamber was taken up again (del Cerro et al., 1985), followed by transplantation of retinal cell aggregates or microaggregates to the retina (Turner and Blair, 1986; del Cerro et al., 1991; Gouras et al., 1992).

2.2.1. Transplantation of dissociated cells or cell aggregates

Early on, most studies used freshly harvested early neonatal or fetal retinal cells. Del Cerro et al. transplanted dissociated postnatal cells to the subretinal space of light-damaged rats (del Cerro et al., 1991). After retrograde labeling retinal ganglion cells of P4 rat retina by rhodamine injection into the superior colliculus (SC), inner and outer retinal layers were horizontally separated using trypsin and a filter membrane, and transplanted to the vitreous of light-damaged rats (del Cerro et al., 1990). Isolated outer retinal layers did not survive well in the vitreous, whereas isolated inner retinal layers developed primitive photoreceptors. Later studies included transplantation of dissociated human retinal cells to the subretinal space (DiLoreto et al., 1996), leading to a Phase I clinical trial in India (Das et al., 1999) (see section 7).

Gouras et al. transplanted dissociated adult rat photoreceptors to 4-6 months old RCS rats (Gouras et al., 1991a). Transplanted cells slowly degenerated over time and only showed rudimentary outer segments at 2 weeks post surgery although some surviving photoreceptor cell bodies could be seen after several months. Then, transplantation of dissociated cells was compared with transplants of microaggregates (small retinal pieces) of neonatal mouse retina to rd mice (Gouras et al., 1992). In contrast to transplants of dissociated cells, microaggregate transplants developed small patches of outer segments in 50% of the cases where the small pieces were randomly placed in the correct orientation into the subretinal space, with photoreceptor progenitors facing the RPE. Such transplanted photoreceptors could survive and maintain their outer segments long-term (Gouras and Tanabe, 2003). However, after transplantation of retinal microaggregates to retinal degenerate cats, photoreceptors mostly formed rosettes (spheres of photoreceptors with outer segments in the center) (Ivert et al., 1998). Rosette formation thus showed some level of laminar organization that could not be achieved with dissociated cells.

Similarly, another group compared transplants of dissociated cells and aggregates and found photoreceptor rosette formation only in aggregate transplants (Juliusson et al., 1993).

The model of transplanting cell aggregates (in contrast to dissociated cells) into a retinal injury site (Turner and Blair, 1986) showed that immature cells can develop retinal layers in rosettes, that embryonic donor ages develop better lamination than postnatal donor ages (Aramant et al., 1988), express glial and neuronal retinal cell markers (Seiler and Turner, 1988; Aramant et al., 1990a), grow processes into the host inner plexiform layer and form synapses (Aramant and Seiler, 1995) and that xenografts of human fetal retinal cells develop most retinal cell types in immunosuppressed or immunodeficient rat recipients (Aramant et al., 1990b; Aramant and Seiler, 1994). After 8 months of cryopreservation, fetal retinal aggregates can be transplanted and survive (Aramant and Seiler, 1991). Early on in Turner's laboratory it was found out that less disrupted cell aggregates formed transplants containing many more photoreceptors with outer segments in form of rosettes (Aramant et al., 1988). However, the organization of such transplants was still very unsatisfactory.

In summary, cell aggregates clearly showed better results than dissociated cells.

2.2.2. Transplants of retinal or photoreceptor sheets

Silverman developed a method to isolate photoreceptor sheets of 8d postnatal and adult retina by gelatin embedding and vibratome sectioning retinal wholemounts down to the photoreceptor layer (Silverman and Hughes, 1989). These sheets were then transplanted into light-damaged rats using a special instrument. The transplantation method consisted of rolling up the gelatin embedded donor tissue to fit into a round nozzle, and then unfolding it after insertion into the subretinal space. This required the formation of a subretinal bleb prior to delivering the tissue, and subsequent retinal reattachment. The amount of fluid required to inject the tissue caused some trauma to the host and the donor tissue. However, the transplanted isolated sheet photoreceptors did not maintain outer segments; outer segments were only seen when portions of inner retina were left together with the photoreceptor sheet (Silverman and Hughes, 1989; Silverman et al., 1992a). Photoreceptor isolation was improved by using an excimer laser instead of a vibratome (Huang et al., 1998; Tezel and Kaplan, 1998). This procedure was also used for early clinical safety trials with transplanting adult photoreceptor sheets to RP patients (Kaplan et al., 1997) (see section 7).

The Silverman method (with modifications) was taken up by several researchers who either transplanted photoreceptor sheets (Mohand-Said et al., 1997; Ghosh et al., 1999c), full-thickness fetal (Ghosh et al., 1998) or adult retina (Schuschereba and Silverman, 1992; Ghosh et al., 1999c; Wasselius and Ghosh, 2001). Ghosh at al. compared the vibratome sectioning method with their “full-thickness” retinal transplant method and concluded the trauma induced by vibratome sectioning led to disturbed lamination and lower transplant survival (Ghosh et al., 1999c).

Independently, our group developed an instrument and procedure to transplant intact fetal retinal sheets - freshly isolated alone or together with its RPE - to the subretinal space of a degenerating retina (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Aramant et al., 1999; Aramant and Seiler, 2002b) (see section 4). The implantation instrument (reviewed in Aramant and Seiler, 2002a) does not inject the sheet, but allows the fragile donor tissue to be gently placed in its correct orientation in a minimal amount of fluid. No retinal reattachment is necessary after delivering the donor tissue in this way. These sheet transplants can integrate with a degenerating retina and restore visual responses as shown in several rat models of retinal degeneration (Woch et al., 2001; Sagdullaev et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2004b; Seiler et al., 2005; Seiler et al., 2008b; Seiler et al., 2010a) (see sections 4 and 6, Figures 1-8).

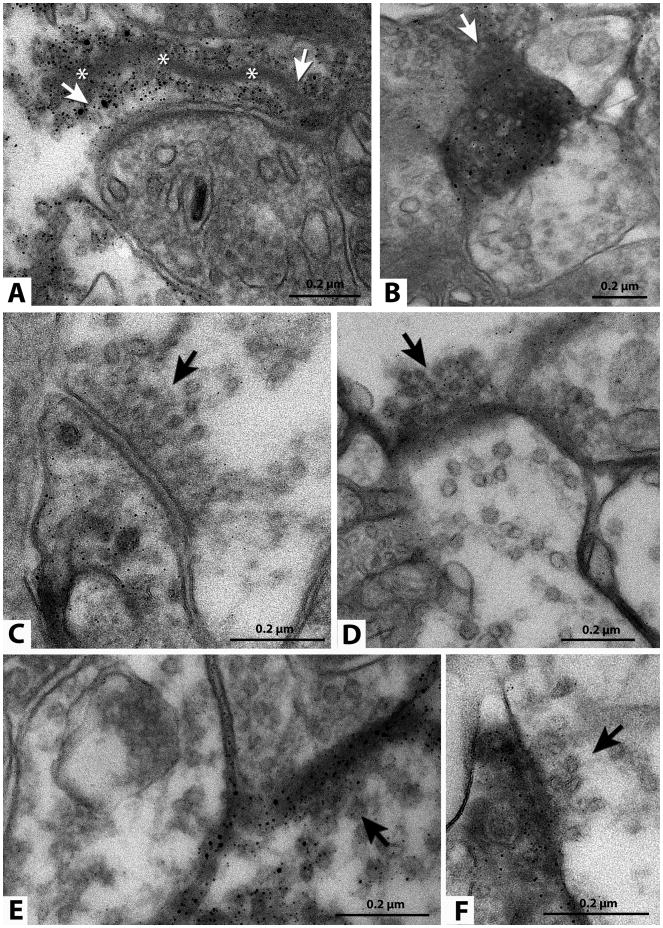

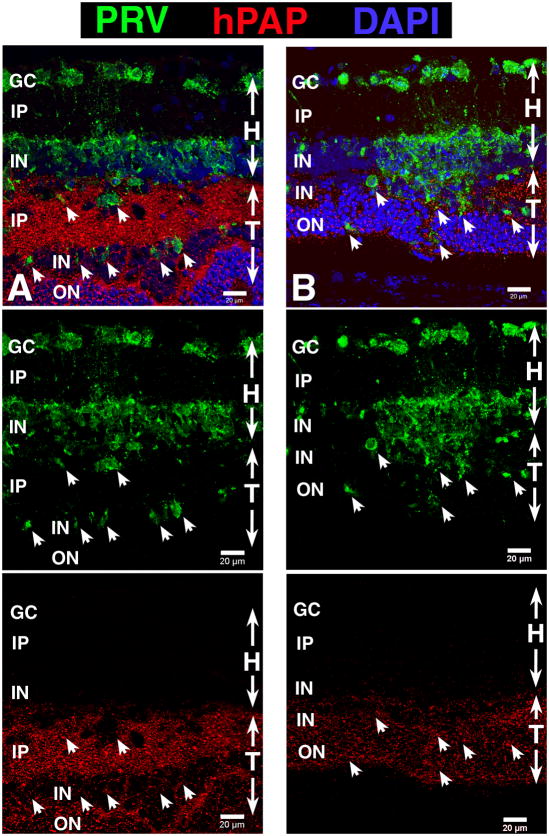

Figure 8. Ultrastructural demonstration of synaptic connectivity. Direct evidence.

Transplant processes and synapses in the inner plexiform layer of the host retina (images from 4 different rats). Immunohistochemistry for human placental alkaline phosphatase, recognizable as silver grains. The sections could not be counterstained therefore many apparent synapses were too diffuse to document clearly. Arrows indicate a presynaptic element of an apparent synapse between transplant and host cell. (A) Labeled ribbon synapse. A long synaptic ribbon is indicated by asterisks. Labeled processes are presynaptic in A, D and E, and postsynaptic in B, C and F. Scale bars: 0.2 μm.

Reprinted with permission from Seiler et al. 2010: Visual restoration and transplant connectivity in degenerate rats implanted with retinal progenitor sheets. Eur J. Neurosci, 31(3):508-520. Copyright J. Wiley & Sons.

In summary, more-or-less inferior results occur when the retina is sliced on different levels; this is likely due to the damage to the scaffold of Muller glial cells that are responsible for organization and nourishment of the neuronal cells.

3. Retinal donor tissue

Preparation of the retinal donor tissue is crucial for the survival and development of the transplant. The dissection has to be done very carefully, with minimal touching of the retina. In our experiments, donor tissue is kept cold in Hibernate E medium which can protect the tissue for several days. Ghosh's group is using oxygenated Ames' medium, originally used for electrophysiology of retinal wholemounts (e.g., Ghosh et al., 1998; Wasselius and Ghosh, 2001).

3.1. Fetal cells

Extensive preclinical studies to find the optimal donor tissue for transplantation in the central nervous system (CNS) took place around the 1980s in Sweden for Parkinson's patients (Lindvall et al., 1988). Unequivocally, these studies indicated that fetal donor tissue was the tissue of choice (Brundin et al., 1988; Lindvall and Bjorklund, 2004). A 2004 review stated “… intrastriatal transplants of fetal mesencephalic tissue in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients have provided proof-of-principle for the cell replacement strategy in this disorder” and “Most probably, fetal mesencephalic grafts will continue to be the golden standard …” (Lindvall and Bjorklund, 2004). In a 2011 review, the same authors discuss a European Research project called TransEuro, started in 2010, where fetal cell grafting was taken up again to optimize and standardize the therapy for PD “while waiting for the new opportunities offered by stem cell technology” because “… stem cell-derived DA neurons, suitable for use in clinical trials, are not going to be available any time soon” (Lindvall and Bjorklund, 2011).

We can presume that the overall principles apply throughout the CNS including the eye, i.e., fetal cells are optimal for transplantation. Many retinal transplantation studies from 1980s and 1990s indicated that fetal cells were optimal in a progressive scale from dissociated cells to intact sheets (see section 3.2 below).

In spite of the ethical and supply issues, fetal transplants can be done ethically and safely following the protocol of Helsinki from otherwise discarded tissue provided that there is complete separation between donor and tissue use for the recipient, clean medical history of the donor, informed consents (both donor and recipient), and no incentive for abortions. Results with fetal tissue provide the basis for the proof of principle of what retinal transplants can do in the best case. In this interim, while aiding to develop other approaches like stem cells for clinical use, many patients might be helped.

3.2. Advantages of fetal retinal sheets

As a general overview, the retinal sheets are part of an organ: the eye. Science has been successful with organ transplants like heart, lung, kidney, liver etc. Transplants of intact fetal sheets with its pigment epithelium have clear advantages. It is a method that takes into account different sick parts of a degenerating retina. Degeneration of RPE or photoreceptors is either directly or indirectly related to each other, and then the damage progressively spreads to the nearest layers. Results have shown that restored communication with the host retina can take place not necessarily by the photoreceptors but through other transplant retinal cells (Seiler et al., 2008b; Seiler et al., 2012) (see section 6.2). As a piece of a developing organ, fetal retinal tissue has already early on developed a primordial circuitry and the cells are committed to be retinal cells.

Allografts of fetal tissue face a lower chance of rejection because of the “immune privilege” of the subretinal space (Streilein et al., 2002; Niederkorn, 2006). Although neural retina is non-immunogenic, the RPE and the microglial cells in the donor retina are immunogenic (Ma and Streilein, 1998; Streilein et al., 2002). Microglial cells are associated with blood vessels and migrate postnatally into the rat retina (Ashwell et al., 1989) and, into the human retina, from 16 weeks gestation (Provis et al., 1997). Fetal retinal tissue is less immunogenic than adult tissue because it contains less microglia and fewer, immature blood vessels (Ashwell et al., 1989; Diaz-Araya et al., 1995). Fetal cells have few surface markers that make them recognizable as foreign cells. However, macrophages can act as antigen presenting cells in the subretinal space (McMenamin and Loeffler, 1990) when cografting RPE and retina. Interestingly, xenografts of full-thickness fetal rat retina can survive as laminated sheets in rabbits – however, without development of outer segments and only rudimentary inner segments – whereas fragmented fetal rat grafts are rejected (Ghosh et al., 2008). Similarly, allografted sheets of neonatal mouse RPE survive when transplanted to the kidney capsule whereas dissociated cells are rejected (Wenkel and Streilein, 2000).

The fetal cells have a high capacity to sprout processes, and to produce trophic substances that will aid host and transplant cells in different ways. Fetal cells can multiply, so that the transplants can grow to cover a larger area, usually doubling in size. A fully developed sheet transplant contains much more cells than at the time of surgery. Fetal cells can overcome the trauma of transplantation much easier than adult cells because fetal retinal cells do not depend as much on oxygen as adult cells (Wasselius and Ghosh, 2001).

However, photoreceptors and their precursors develop mostly postnatally; thus it is impossible to isolate photoreceptor progenitors from fetal retinal sheets without disrupting the sheets. Gosh and collaborators have developed procedures for culturing fetal retinal sheets (Ghosh et al., 2009) and whole eye cups (Engelsberg and Ghosh, 2011). Tissue culture induces selective loss of inner retinal cells. They argue that this is a better way to enrich photoreceptor progenitors than cutting photoreceptor sheets from retinal wholemounts or enriching photoreceptor progenitors from dissociated retinal cells. No transplantation studies have been published yet.

Yang et al. transplanted either photoreceptor sheets (sliced from retinal wholemounts) or whole retinal sheets of postnatal P8 retina to 3-month-old P23H rats, a slow retinal degeneration model (Yang et al., 2010b) using a modification of Silverman's method. Both types of transplants improved the amplitude of the ERG b-wave to same extent and had a positive paracrine effect to rescue host cones.

A comparison of different rat donor ages in aggregate transplants showed that embryonic donor tissue developed better lamination and integrated better than postnatal donor tissue (Aramant et al., 1988). In a study comparing different donor ages of retinal aggregate transplants after 8 months of cryopreservation, rat E16 donor retina developed better than older or younger donor ages. However, freshly harvested retinas developed better laminated transplants than cryopreserved retinas (Aramant and Seiler, 1991). Similarly, aggregate transplants of human fetal retina grew larger and were better organized when derived from donor tissue of 9-11 weeks post-conception compared to older human donor tissue (Aramant and Seiler, 1994).

Our first published study of intact fetal rat retinal sheet transplants to light-damaged rats used E15 to E21 donors (Seiler and Aramant, 1998). Most of our later studies used E19-20 donor tissue (Woch et al., 2001; Sagdullaev et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2004b; Seiler et al., 2010a; Yang et al., 2010a).

Other laboratories have transplanted adult retinal sheets in normal rabbits (Schuschereba and Silverman, 1992; Wasselius and Ghosh, 2001). Rabbit retina is special because it contains no blood vessels outside the visual streak, and can be maintained viable in vitro (e.g. for recording) for relatively long time. Schuschereba's study reported that the transplant photoreceptor layer was reduced to 50% thickness after only 2 weeks survival (Schuschereba and Silverman, 1992). Wasselius' study showed long-term survival of adult retinal sheet transplants in normal rabbits, using optimized medium and storage conditions before transplantation (Wasselius and Ghosh, 2001). In contrast, fragmented transplants did not survive. However, all layers of the normal host retina severely degenerated in the transplant area, and the transplants were mostly separated from the host retina although small areas of connections were seen. This study was not repeated in retinal degeneration models.

On the other hand, transplantation of intact fetal retinal sheets can consistently achieve a large continuous layer of transplant photoreceptors with outer segments in contact with host or donor RPE, in recipients that have lost their photoreceptor layer (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Aramant et al., 1999; Seiler and Aramant, 2001; Aramant and Seiler, 2002b).

In summary, early in the 1990s, we hypothesized that the optimal donor tissue for transplantation in the eye should be freshly harvested fetal retinal sheets because transplants of intact fetal retinal sheets preserve the environment of the developing donor retina including the Muller cells that are responsible for the organization and nourishment of the retinal neurons.

3.3. Retinal stem cells, photoreceptor precursors - Single cells and neurospheres

Transplantation of dissociated cells has the advantage that only a small, self-sealing incision is necessary to deliver the cells. However, long-term survival of photoreceptors is poor in transplants of dissociated retinal cells (Gouras et al., 1991a; Gouras et al., 1991b; Mansergh et al., 2010); photoreceptors in microaggregates fare better if photoreceptors come in contact with RPE (Gouras et al., 1994; Gouras and Tanabe, 2003). Only one study in 1999 showed the development of a new photoreceptor layer with outer segments from mechanically dissociated postnatal retinal cell transplants to rd mice (Kwan et al., 1999). No other study using dissociated cells has replicated these results although transplanted photoreceptor precursors can develop outer segments and synaptic connections when they integrate into an existing outer nuclear layer (MacLaren et al., 2006; Bartsch et al., 2008; Pearson et al., 2012).

Since the source of fetal tissue is limited and controversial, most research is now focused on expanding cells (either derived from fetal origin, adult tissue or pluripotent stem cells) in tissue culture before transplantation. Recent research advances have made it possible to create three-dimensional optic eye cup-like tissue from pluripotent stem cells (Eiraku et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2012; Nakano et al. 2012) (see section 7.6).

3.3.1. Retinal stem cells

Retinal stem cells have been isolated from fetal retina (Chacko et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2004; Klassen et al., 2008), postnatal retina (Klassen et al., 2004a), Muller glial cells (Das et al., 2006) or from the ciliary margin of the eye (review: Djojosubroto and Arsenijevic, 2008). However, it has been questioned whether adult ciliary epithelial cells represent retinal stem cells (Cicero et al., 2009). In addition, ciliary epithelial cells derived from NRL-GFP mice fail to differentiate into rod photoreceptors (Gualdoni et al., 2010).

Undifferentiated retinal stem cells remain proliferative in culture over several passages (usually by the addition of EGF and/or FGF). Differentiation to various retinal cell types is induced by removing growth factors and adding retinoic acid and/or serum. The photoreceptor differentiation potential of adult ciliary stem cells can be much improved by combined transduction of OTX2 and CRX together with the modulation of Chx10 (Inoue et al., 2010).

After transplantation to the vitreous or subretinal space, a subpopulation of retinal stem cells can integrate into the retina, differentiate and show transient trophic effects in retinal degeneration models (Klassen et al., 2004a). Klassen et al. transplanted neurospheres of retinal progenitor cells to the subretinal space of rho −/− mice (Klassen et al., 2004a), whereas other laboratories transplanted dissociated cells (Yang et al., 2002; Chacko et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2005). Survival, differentiation and integration of retinal progenitor cell transplants can be somewhat improved by matrix embedding (Redenti et al., 2009; Tucker et al., 2010), indicating that maintaining cell-cell interactions is important.

3.3.2. Freshly isolated or cultured photoreceptor precursors

Rod precursor cells are postmitotic and express the transcription factors NRL and CRX. MacLaren et al. (MacLaren et al., 2006) isolated mouse photoreceptor precursor cells from freshly harvested postnatal retinas (P1-7) and transplanted them as dissociated cells. Using the NRL-GFP mouse as donor, photoreceptor precursors could be enriched by FACS sorting. A small percentage (0.1 – 0.2%) of the transplanted cells integrated into the photoreceptor layer of normal and rho−/− retina (see below). More recently, photoreceptor progenitor cells were isolated by FACS sorting from CRX-GFP mice and transplanted to two mouse models of Leber's Congenital Amaurosis (Lakowski et al., 2010). Dissociated cells (derived from the rho-GFP mouse) survived and differentiated better after transplantation when freshly isolated than after several passages of cell culture (Mansergh et al., 2010). After transplantation of freshly harvested photoreceptor precursors derived from NRL-GFP mice to normal adult mice, a significant decrease of integrated photoreceptors was seen starting at 4 months due to invasion of macrophages, and very few cells could be found surviving in the retina up to 12 months after transplantation (West et al., 2010). At 4 months after transplantation, immune suppression with cyclosporine A increased the number of the few integrated cells about 4-fold. One main inference of the study was that the problem with survival could be solved with immunosuppression. However, immunosuppression has many side effects, both on the recipient and on the transplants. An important comment: fetal retinal sheet transplants survive long-term without immunosuppression (e.g. Ghosh et al., 1999b; Thomas et al., 2004b; Seiler et al., 2010a; Yang et al., 2010a). It would be very difficult to justify systemic immunosuppression in a clinical setting for treating an eye disease because it is not life-threatening like heart or kidney diseases.

Sorting of postnatal retinal cells for rod precursor cell surface markers CD73 (and absence of CD24) increases the efficiency of photoreceptor integration into the outer nuclear layer and is 2-3 times more effective than only sorting for the expression of the GFP-NRL transgene (Eberle et al., 2011; Lakowski et al., 2011). At 3 weeks after transplantation, the percentages of integrated cells varied greatly between these 2 publications. Lakowski (Lakowski et al., 2011), injecting 200,000 cells, reported integration of in average 6%, up to 16% of the transplanted cells when sorting for CD74 and excluding CD24, compared to an average integration of 2.3%, up to maximum 4% for NRL-GFP sorted cells. Eberle (Eberle et al., 2011), injecting 400,000 cells, reported integration of 0.55% of CD73-sorted cells, and only integration of 0.17% unsorted cells.

Recently, mouse NRL-GFP+ sorted rod precursors have been transplanted into a mouse model of rod degeneration lacking rod transducin (Gnat1−/− mice) using an improved transplantation procedure, either performing scleral puncture or retinal detachment before cell injection to two transplantation sites instead of one (Pearson et al., 2012). This resulted in the integration of in average 8-9%, up to 16% of transplanted cells into the outer nuclear layer. Experiments were analyzed 4-6 weeks after transplantation, with many different methods, from cellular to behavioral, demonstrating that transplanted cells developed photoreceptor morphology, synaptic connectivity and light responses and could elicit light-evoked responses in the brain (although no full-field ERGs). Transplanted mice showed visual improvements in dark-adapted optokinetic testing and water maze (in dim light). The authors claimed that “So far there have been no convincing reports of photoreceptor-cell transplantation actually improving the recipient's vision …”, and thus their study was the first showing visual restoration by photoreceptor transplantation, ignoring many previous studies (see section 5).

3.3.3. Retinal progenitors and photoreceptor precursors derived from pluripotent stem cells

Mouse postnatal day 5 (the best age to isolate photoreceptor precursors) would correspond to late second or early third trimester human fetal tissue. This would be impossible to justify and obtain. Therefore, another cell source needs to be found. Retinal and photoreceptor progenitor cells have been derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) (Lamba et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2009; Yue et al., 2010; Meyer et al., 2011; Hambright et al., 2012; Clarke et al. 2012) and from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Lamba et al., 2010; Parameswaran et al., 2010; Meyer et al., 2011; Tucker et al., 2011). Lamba et al. (Lamba et al., 2009) transplanted hESC-derived retinal progenitors, differentiated according to a previously published protocol to newborn and adult wild-type mice and to adult transgenic CRX −/− mice, a retinal degeneration model. Transplanted cells migrated into all cell layers in newborn mice and preferentially into the outer nuclear layer in adult mice. Cells that developed into photoreceptors did not develop outer segments in the CRX −/− mice. A study in 2010 showed a differentiation protocol for iPS towards photoreceptors and a picture of three transplanted cells that had successfully integrated into the outer nuclear layer of a normal mouse, expressing recoverin and OTX2 (Lamba et al., 2010). Integrated transplanted cells also expressed rhodopsin in their cytoplasm, but no outer segments were shown. Using mouse iPS cell-derived retinal progenitors, Tucker et al. (2011) showed that transplanted cells (labeled with dsRed) integrated into the outer nuclear layer of rho−/− mice and expressed the outer segment marker ROM1 (shown 3 weeks after transplantation). Undifferentiated cells expressing the marker SSEA1 needed to be removed twice prior to transplantation to avoid teratoma formation. A recent study (Hambright et al., 2012) compared the survival and differentiation of hESC-derived retinal progenitor cells that were injected either into the subretinal space or vitreous of normal mice, and analyzed at 3 weeks and 3 months after transplantation. Surprisingly, the xenografts survived without immunosuppression provided there was no break of the blood-retinal barrier. However, this surgery approach (injection through the cornea) would not apply to human vitreoretinal surgery, and the study was not performed in a retinal degeneration model. Cells transplanted to the subretinal space developed photoreceptor markers whereas cells in the vitreous failed to differentiate. Cells transplanted to the vitreous migrated and integrated into the inner retinal layers, but cells from subretinal grafts only migrated into the outer nuclear layer when there was damage to the outer retina due to the injection.

3.3.4. Summary

As the studies above indicate, the foremost issue with transplantation of dissociated cells is cell survival and integration. Although some cells will integrate into the host retina, a high percentage of dissociated transplanted photoreceptor precursors remain in the subretinal space without contact to the host retina (MacLaren et al., 2006; Bartsch et al., 2008; Hambright et al., 2012). Retinal integration and morphological development of dissociated photoreceptor precursors depends on the developmental stage, process of mitosis, the donor age, selection of photoreceptor precursors, disruption of the glial barrier of the host retina and on the status of the host.

Development of normal photoreceptor morphology of the integrated transplanted photoreceptor precursors depends on the presence of the host outer nuclear layer; transplanted cells will not develop normal morphology of outer segments when transplanted to a recipient that has lost most photoreceptors such as rd or severely light-damaged mice (MacLaren et al., 2006; Lamba et al., 2009). When transplanting freshly harvested dissociated retinal cells, it appears that photoreceptor progenitor cells derived from early postnatal ages (P1 – P7) integrated into the host retina more efficiently than donor cells derived from either embryonic or older ages (MacLaren et al., 2006). P1 – P7 photoreceptor progenitor cells have stopped dividing, but are still immature and do not express markers of mature photoreceptors such as opsin and recoverin. They are in their strongest morphological and most suitable stage for single cell transplantation.

On the other hand, integration of donor cones after transplantation into two genetic models of Leber's congenital amaurosis (Crb1rd8/rd8 and Gucy2e−/− mouse) was only achieved when transplanting embryonic donor tissue (FACS-sorted from transgenic GFP-CRX mice that express GFP in all photoreceptor progenitors) (Lakowski et al., 2010). Cone integration efficiency was highest in the cone-deficient Gucy2e−/− retina. However, dissociated adult photoreceptors can also integrate into the outer nuclear layer of normal mouse retina when analyzed 2 weeks after transplantation (Gust and Reh, 2011), but they died rapidly after plating on coverslips in vitro. Long-term survival of such transplants is unknown but is not expected.

In summary, dissociated retinal cells (retinal stem cells, photoreceptor precursors, or adult retinal cells) survive less well after transplantation and are more easily rejected than sheets or microaggregates. Only a small percentage of transplanted cells integrate into the host retina and develop morphology of photoreceptors provided there is an existing host outer nuclear layer. All this indicates that a scaffold of Muller cells and also likely a healthy RPE is important for full photoreceptor development in vivo. The optimal donor age timing for cell transplantation is likely different for diverse retinal cell types depending on their last mitosis and applies only to transplantation of single cell suspensions, not to sheets.

3.4. Donor cell label

It is necessary to identify the donor tissue in the host to demonstrate cell differentiation, survival and integration after transplantation. Several groups have used nuclear labels that are taken up by dividing cells during DNA synthesis such as 3H-thymidine (del Cerro et al., 1990; Gouras et al., 1991a; Du et al., 1992) and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Seiler and Aramant, 1995, 1998; Aramant et al., 1999); and the nuclear label DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole hydrochloride) (Wasselius and Ghosh, 2001). DAPI has however the disadvantage that it can be taken up by host macrophages, especially when dissociated cells are transplanted (Castanheira et al., 2009). Nuclear labels can only show cell migration, not extension of processes into the host. Donor tissue has also been prelabeled using dyes such as DiI (Silverman and Hughes, 1989; Tian et al., 2010), CFDA (Chacko et al., 2000), quantum dots (Wang et al., 2010a), or by gene transfection (Chacko et al., 2003; Bartsch et al., 2008).

However, genetically labeled donor tissue provides a label that also shows cytoplasmic processes and cannot be transferred by diffusion to host cells. Gouras et al. used donor tissue derived from transgenic mice expressing E.coli β-galactosidase (β-gal) in rods transplanted to a recipient that expressed β-gal in rod bipolar cells (Gouras and Tanabe, 2003). Transgenic animals have been created which express fluorescent proteins such as EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) - either in all cells (Okabe et al., 1997; Park et al., 2001; Hadjantonakis et al., 2002) or specifically in photoreceptor precursors (Chan et al., 2004; Akimoto et al., 2006). Such animals have been used in a variety of studies, ranging from transplantation of cultured retinal progenitors (Klassen et al., 2004b; Klassen et al., 2008; Mansergh et al., 2010), freshly isolated photoreceptor precursors (MacLaren et al., 2006; Bartsch et al., 2008) to retinal sheets (Arai et al., 2004). A rat strain in which all cells express human placental alkaline phosphatase (hPAP) developed by Dr. Sandgren, University of Wisconsin (Kisseberth et al., 1999), has been used by our laboratory since 2001 in all our experiments. This strain was cross-bred with pigmented ACI rats (RT1av1, Harlan Laboratories) to obtain pigmented donors. 50% of the offspring will express hPAP which can be detected by a simple histochemical reaction or by immunohistochemistry. Figure 1 A,B; 2A, 5 – 8 show examples of hPAP stained transplants. The label is expressed in the cytoplasm, not in nuclei, and therefore shows up much fainter in nuclear layers. A list of the antibodies used for the figures is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. List of antibodies used in figures.

| Antibody Specificity | Species | Description | Dilution | Supplier | Shown in Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue opsin | rabbit | Blue-sensitive cones | 1:2000 | Chemicon, Temecula CA | 2C |

| Calbindin | rabbit | Marker for horizontal and some amacrine cells | 1:1000 | Chemicon | 1A |

| hPAP | mouse | Human placental alkaline phosphatase (donor label) Punctate stain | 1:500 (fl. 2nd ab) | Chemicon | 1A, B |

| 1:1K -1:2K (Elite ABC method) | Chemicon | 7, 8 | |||

| hPAP | mouse | Human placental alkaline phosphatase (donor label) Punctate stain | 1:600 | Sigma, St. Louis, MO | 5A,B |

| hPAP | rabbit | Human placental alkaline phosphatase (donor label) smooth stain | 1:50 | Epitomics, Burlingame CA | 2A, 6A-C |

| PKC alpha | rabbit | Rod bipolar cells | 1:125 | Oxford Biomedical, Oxford MI | 1B |

| PKC alpha | rabbit | Rod bipolar cells | 1:100 | Biodesign, Saco ME | 2C |

| PRV | rabbit | Pseudorabies virus | 1:5000 | gift of Dr. Enquist, Princeton University (Card et al., 1990) | 5A,B |

| PSD-95 | mouse | Post-synaptic density protein 95 | 1:500 | Stressgen, Victoria, BC, Canada | 6C |

| Recoverin | mouse | Rod and cone photoreceptors, cone bipolar cells | 1:500 | gift of Dr. McGinnis, University of Oklahoma (McGinnis et al., 1997) | 6 B1,B2 |

| Red-green opsin | rabbit | Red-green sensitive cones | 1:2000 | Chemicon | 2B |

| Rhodopsin (rho1D4) | mouse | rods | 1:50 | gift of Dr. Molday, University of British Columbia (Molday and MacKenzie, 1983) | 2B |

| Synapsin-1 | mouse | Synaptic layers | 1:500 | Chemicon | 6 A1,A2 |

| Syntaxin-1 (HPC-1) | mouse | Synaptic layers, amacrine cells | 1:500 | gift of Dr. Colin Barnstable, now Penn State Univ. (Barnstable et al., 1985) | 2A |

4. Transplantation of freshly harvested retinal progenitor sheets to repair degenerated retinas

4.1. Introduction

We hypothesized that the optimal organized transplant in the eye should be from a fetal intact piece, a retinal sheet with its primordial circuitry formed and cells that were committed to differentiate into various retinal cells.

In all studies, the ARVO statement for use of animals in research was followed, and all protocols were approved and monitored by the local IACUC committees (of the University of Louisville, the Doheny Eye Research Institute, and UC Irvine).

Our first published study showed transplantation of fetal retina to a rat light damage model (Seiler and Aramant, 1998). Using a custom-made instrument and procedure, the donor tissue was gently placed – not injected – into the subretinal space. The procedure has been described and reviewed in detail in Aramant and Seiler (2002a). The method was first presented at the Neuroscience Meeting in 1995.

A Swedish group also transplanted fetal “full thickness” retina, but, - in contrast to our group, to normal rabbit retina (Ghosh et al., 1998; Ghosh et al., 1999a; Ghosh et al., 1999b) and normal pig retina (Ghosh and Arner, 2002). They switched to the pig model of retinal degeneration later (Ghosh et al., 2004). Their transplants could develop good lamination, but they only showed integration with the inner layers of the avascular rabbit retina which appeared to degenerate over the transplant. However, in the vascularized pig and cat retina, the transplant remained mostly separated from the host retina (Ghosh and Arner, 2002; Bragadottir and Narfstrom, 2003; Ghosh et al., 2004). This was likely due to the more traumatic surgery method that required a retinal bleb and an extra retinotomy for relieving pressure to prevent the tissue to slip out after injection.

In contrast, using our implantation method, fetal sheet transplants could fuse well with the host retina in several rat degeneration models (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Seiler et al., 2005; Seiler et al., 2008b) and in Abyssinian cats (Seiler et al., 2009). Differences between the results of the Swedish work and ours could be the result of the different instrument and procedure used for transplantation.

4.2. Efforts to support donor tissue by matrix embedding

Fetal donor tissue is very fragile, so we thought it may be necessary to embed it in a gel for protection. Early studies used growth factor reduced matrigel (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Seiler et al., 1999), and later medium viscosity (MVG) alginate (Pronova, Oslo, Norway) (Seiler et al., 1999; Seiler and Aramant, 2001). We then decided to omit gel embedding entirely because of complications, such as partial separation of the neural retinal transplant from the host retina with the embedding matrix alginate, as can be seen in Aramant et al. (1999). However, it may be possible to improve the delivery of retina/RPE co-transplants with biomaterial scaffolds of which there are many possibilities available (review Treharne et al., 2011).

4.3. Cografts of fetal retina with RPE (rat and human) - an unique approach (Figure 1)

Many patients with advanced retinal degeneration need transplantation of both RPE, photoreceptors, and other retinal cells. Our retinal transplantation model has successfully demonstrated replacement of RPE and photoreceptors together in animals (Aramant et al., 1999; Woch et al., 2001; Aramant and Seiler, 2002b) and humans (Radtke et al., 2008). This was accomplished by transplanting freshly dissected sheets of fetal-derived (rat or human) neural retina progenitor cells with its RPE into the subretinal space. Such transplants have the potential to benefit retinal diseases with dysfunctional RPE and photoreceptors such as in ARMD and RP.

Dissection of fetal retina together with its RPE is a challenge since there is no adhesion between retina and RPE without developed photoreceptor outer segments. To dissect the RPE cleanly, eye cups were incubated in Dispase (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Using ultrafine forceps, sclera and choroid were gently peeled away, and alginate-embedded pieces of retina with its attached RPE were then transplanted to the subretinal space (Aramant et al., 1999; Woch et al., 2001; Aramant and Seiler, 2002b). The first successful co-transplantation of fetal retina with its RPE was done in RCS rats (Aramant et al., 1999) (Figure 1 A,B). These transplants could restore visual responses in the SC (Woch et al., 2001). In another important preclinical study, we showed that human fetal retina with its RPE could be transplanted to immunodeficient albino athymic nude rats, survive for 8 - 11 months and develop normal lamination with its monolayer of RPE (Aramant and Seiler, 2002b) (Figure 1 C, D, E). This study was the basis for FDA-controlled clinical trials (see section 7).

Gel embedding was later omitted for the clinical trials because the instrument could gently deliver the co-transplants without any protection (Radtke et al., 2002; Radtke et al., 2004; Radtke et al., 2008). In addition, we had noticed that alginate sometimes caused graft-host separation (see section 4.2), and FDA approval would have been needed for using bioscaffolds in patients.

Another group has transplanted gelatin-embedded sheets of fetal human retina and RPE to light-damaged minipigs (without immunosuppression), and reported an improvement in multifocal ERG (Li et al., 2009). These transplants did not differentiate photoreceptors, and contained mostly glial cells. The transplants degenerated over time, likely due to the lack of immunosuppression, with complete degeneration of host and graft retina in the transplant area at 9-12 months.

4.4. Why do not all transplants develop perfectly?

In the rodent eye, a posterior approach had to be used to place the donor tissue into the subretinal space in the center of the eye near the optic disk. A cut is made behind pars plana through sclera, choroid and retina. Then the surgeon “feels” his/her way with the instrument into the subretinal space without seeing how the transplant is placed. Therefore, only 20 - 30 % of the surgeries result in transplants with large laminated areas (e.g. Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Seiler et al., 2008b). Transplants only develop lamination if the transplant photoreceptors can develop in normal interaction with the host or donor RPE. The fetal tissue is very fragile; any misplacement and disturbance can lead to rosette formation.

Transplantation of retina together with its RPE adds additional difficulties since the RPE does not attach well to the retina when outer segments have not yet developed. Treatment of the eye cup with Dispase before dissection is important so choroidal vessels can easily be teased away.

In larger eyes, the surgery is a completely different scenario. The instrument can be used with a standard vitreoretinal surgery approach so that the surgeon can see and be in full control of the delivery with a higher success rate than in rodent eyes (Radtke et al., 2002; Radtke et al., 2008; Seiler et al., 2009) (see success criteria in section 1.4).

However, the study in cats (Seiler et al., 2009) used nozzles for human surgery that were too large and not adapted to the smaller cat eye. In addition, as discussed in that paper, posterior surgery in cats is technically more difficult because more bleeding occurs. Therefore, only 2 of the 4 cats contained transplants, and the donor tissue had folded in on itself. Despite of these issues, the transplants were well integrated with the host retina (Seiler et al., 2009), in contrast to another cat study using a different instrument (Bragadottir and Narfstrom, 2003).

We have not done extensive studies in larger animal models for two reasons: (1) the high costs involved and lack of funding; and (2) the lack of available models at the time we did the experiments. In addition, results can be obtained much faster and in higher numbers with rats although the surgery is more difficult. The transplantation into Abyssinian cats (Seiler et al., 2009) was done at a stage of retinal degeneration when most of the outer nuclear layer was still present, with a short follow-up of 2 months. Therefore, no transplant effect could be seen by electroretinograms (ERGs).

4.5. Imaging of transplants in live rats by 3-D Ocular coherence tomography

To evaluate the placement and structural quality of the transplants in live animals, retinal transplants were analyzed using optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Thomas et al., 2006a; Seiler et al., 2010b). Initial studies were done with single scans of a Stratus OCT-3 (Thomas et al., 2006a) which gave mainly information whether the transplant had been correctly placed into the subretinal space. However, it was difficult to clearly identify laminated transplants. In a later study (Seiler et al., 2010b), using a better setup with a Fourier domain optical coherence tomography (FDOCT) system (scanning of 139 or 199 consecutive slices), the laminar structure of the transplants and surgical defects, such as RPE/choroid damage could be detected with an accuracy rate between 83 and 99%. Three-dimensional projections showed the transplant position in the retina in relation to the optic disc and the growth of the transplant.

4.6 Differentiation of retinal cell types in retinal sheet transplants and comparison with the degenerated host retina (Figures 1 + 2)

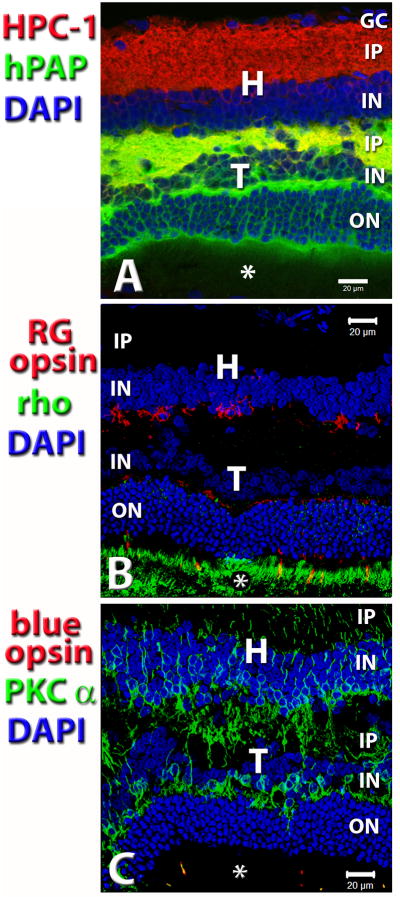

Figure 2. Analysis of marker expression and integration between transplant and host – indirect evidence that transplant is responsible for restoration of visual function.

Laminated transplant in S334ter-3 rat with responses in the superior colliculus (SC). Confocal projection stacks, stained for antibodies listed on the left side. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Photoreceptor outer segments are indicated by asterisks. Retinal transplant, age 8.5 mo., 7.4 mo. post surgery. This rat had very good visual sensitivity; the threshold was at −2.2 log cd/m2. (A) Donor cell label hPAP (green) in combination with anti-Syntaxin-1 (HPC-1; red). HPC-1 stains synaptic layers and, more faintly, the cytoplasm of amacrine cells in the inner nuclear layers. (B) red-green (RG) opsin (red) in combination with rhodopsin (green). Strong staining of transplant outer segments for rhodopsin. Note that there is no rhodopsin staining in the host retina. There are scattered cell bodies with processes of residual RG opsin immunoreactive host cones (red) at the transplant-host interface. Cone outer segments can only be seen in the transplant. Consequently, only transplant photoreceptors can send strong signals to the brain. Cone opsin also stains cone terminals in the outer plexiform layer of the transplant. (C) Double label of PKC alpha (green) which stains rod bipolar cells and blue opsin (red) that stains blue-sensitive cones. PKC staining of bipolar cells is stronger in the transplant than in the host retina. Note the good integration. Outer segments of blue cones (two samples) can only be seen in the transplant. Scale bars: 20 μm. - Reprinted with permission from Yang et al., 2010: Trophic Factors GDNF and BDNF Improve Function of Retinal Sheet Transplants. Exp Eye Res 91: 727-738 (part of Figure 7). Copyright Elsevier.

With the exception of ganglion cells, retinal sheet transplants can develop all retinal cell types, including fully differentiated photoreceptors in recipients of several retinal degeneration models (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Aramant et al., 1999; Aramant and Seiler, 2002b) (see Figures 1A,B, 2B, 6B1). Both rods and cones develop outer segments when in contact with either host or donor RPE. In general, the inner retinal layers of the transplants are less developed, specifically the inner nuclear and plexiform layer is thinner than of the host retina. Horizontal cells often show stronger immunoreactivity for Calbindin in the transplant than in the host (Figure 1A). In addition, transplants contain many rod bipolar cells which show stronger PKC alpha immunoreactivity and a more normal mGluR6 immunoreactivity at their dendritic tips in the outer plexiform layer than bipolar cells in the host retina (Seiler et al., 2008a; Yang et al., 2010a) (examples in Figures 1B, 2C).

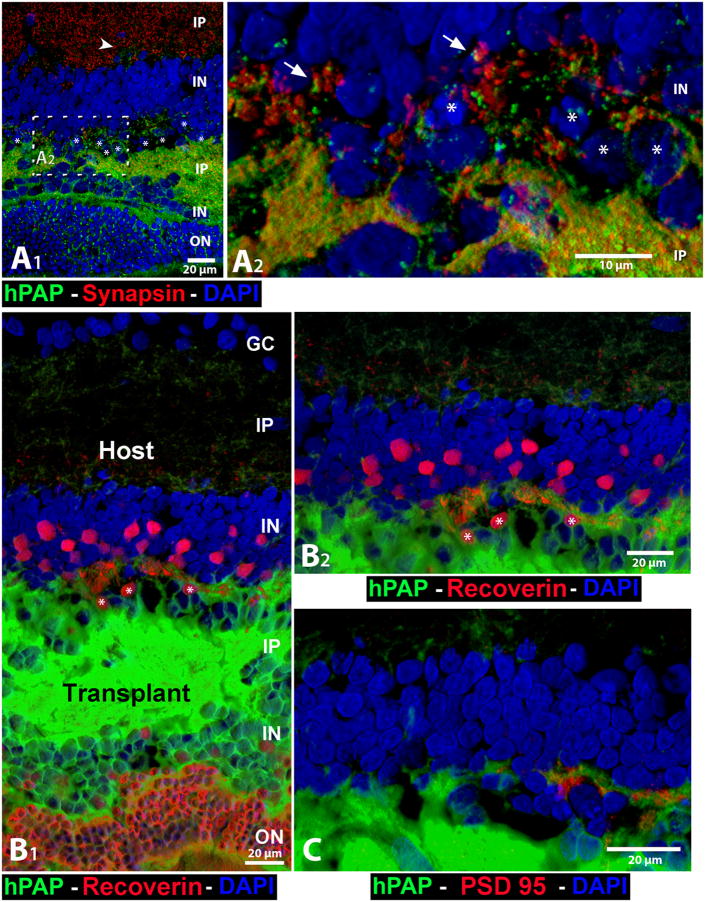

Figure 6. Interface transplant-host: cell and synaptic markers.

The cytoplasm of all donor cells, including their processes, is labeled with hPAP (green) in their cytoplasm (not the nuclei). Note the green donor cell processes in the host inner plexiform layer (IP), indicating outgrowth of processes from the transplant. All images are oriented with the host ganglion cell layer (GC) up. White asterisks (*) indicate nuclei of remnant host cones (containing clumped chromatin). All images are three-dimensional renderings of confocal stacks (not maximum intensity projections). (A1 and A2) Combination of donor label hPAP (green) and synapsin 1 (red, marker for synaptic vesicles and synaptic terminals), and DAPI nuclear label (blue). (A1) Overview. Transplant processes extend past remnants of host cones to the outer plexiform layer of the host. The arrowhead points to a group of transplant processes in the host IP that is slightly visible at this magnification, but can be clearly seen in B1, B2 and in Figure 7. The white dashed box indicates enlargement of the transplant–host interface in A2. (A2) Plentiful areas with potential transplant–host synaptic interactions (transplant processes close to red-stained synaptic structures inside the host area; only 2 examples indicated by arrows. (B1), B2), and C) Unpublished pictures of the same transplant. (B1) Recoverin (red), a marker for photoreceptors and cone bipolar cells and their processes, in combination with hPAP (green). The transplant photoreceptor layer stains strongly for recoverin. There are less, smaller-appearing recoverin-immunoreactive cone bipolar cells in the transplant IN than in the host IN. (B2) Enlargement of transplant-host interface. (C) PSD95 (marker for postsynaptic densities, red) in combination with hPAP (green) at the transplant-host interface. Note transplant process on the right, closely adjacent to PSD95-immunoreactive structures, indicating synaptic connections. E19 retinal transplant (no BDNF-treatment), age 3.0 months, 2.1 months after surgery. Scale bars: 20 μm (A1, B1, B2, C), 10 μm (A2).

(A1, A2) Reprinted with permission from Seiler et al. 2010: Visual restoration and transplant connectivity in degenerate rats implanted with retinal progenitor sheets. Eur J. Neurosci, 31(3):508-520. Copyright J. Wiley & Sons.

Synaptic layers of the transplants stain for diverse synaptic proteins (Seiler et al., 2010a) and show diverse synapse types at the electron microscope (EM) level (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Seiler and Aramant, 2001; Aramant and Seiler, 2002b; Peng et al., 2007; Seiler et al., 2012). The inner plexiform layer of the transplant mostly lacks the lamination found in normal retina (e.g. Figure 8 in Seiler et al., 2008b), and very few, if any, retinal ganglion cells survive (unpublished observations). Recoverin-immunoreactive cone bipolar cells often appear smaller and less numerous than in the host (see Figure 6 B1).

In summary, retinal sheet transplants develop most retinal cell types with the exception of retinal ganglion cells.

4.7. Potential circuitry between transplant and degenerate host retina

In a collaboration with Robert Marc's laboratory (Moran Eye Center, University of Utah), the neurotransmitter expression of retinal sheet transplants has been investigated using computational molecular phenotyping (CMP) (Seiler et al., 2012). CMP combines immunohistochemistry of many different neurochemical markers on adjacent 0.2 μm sections for cell classification and quantitative visualization as tissue theme maps (Marc and Jones, 2002; Jones et al., 2003). The goal of the study was to investigate the potential circuitry of long term retinal fetal sheet transplants that had restored responses in SC of a degenerated host retina. The data indicated that horizontal cells and both glycinergic and GABAergic amacrine cells are involved in a novel circuitry that had generated alternative signal pathways. A normal expression of neurotransmitters of different transplant cell types and areas of neuropil fusion between transplants and host could be seen. Interestingly, amacrine and horizontal cells appeared to be the main cell types involved in connectivity between transplant and host. However, there was an overall reduction of bipolar cells both in host and graft which contradicts previous data about strong PKC alpha expression in the transplants (see section 4.6). The tissue preparation for CMP cannot differentiate between cone and rod bipolar cells. Thus, there was likely a specific loss of cone bipolar cells in the transplant inner nuclear layer which would correspond to unpublished data indicating that there are few recoverin-immunoreactive cone bipolar cells in the transplant (see also Figure 6 B1). This issue needs to be addressed in further studies.

Since transplant photoreceptor signals would have to be transmitted both through transplant and host interneurons before reaching host ganglion cells, “normal” visual processing cannot be expected. However, the data discussed in the sections 5 and 6 indicate that transplants can improve and restore visual function in recipients with retinal degeneration, although with a delay in response time.

5. Transplant photoreceptors are functional and restore visual responses in retinal degeneration models

For our studies, transplants were performed at a stage when most rod photoreceptors had degenerated. The transplants cover a small area of the retina; the initial size of the transplant (in rats) is ca. 1-1.5 mm2, and it doubles in size after full development. This corresponds to ca. 10-20 % of the retina. Thus, we have not been able to distinguish visual responses from transplants from those of host cells by a conventional corneal electroretinogram (ERG) (unpublished observations). This is similar to what has been observed by other researchers (Radner et al., 2001; Gaillard and Sauve, 2007; Pearson et al., 2012). However, it may be possible to show transplant function by more sensitive local ERG methods. Studies investigating transplant rescue effects on remaining photoreceptors have transplanted animals in earlier stages of retinal degeneration for therapeutic intervention, and have been able to find improved ERGs (e.g., Wang et al., 2010b; Tucker et al., 2011).

In addition, even if responses can be recorded from the host retina or retinal ganglion cells, it does not mean that the transplant has any effect on the visual centers in the brain. Therefore, to determine the benefits of transplants for visual function in a recipient with retinal degeneration, transplant effects should be demonstrated not only in the retina, but also in the brain. The transplant should also have an effect on visually guided behavior. It is also important to determine whether beneficial effects remain for a long time after transplantation.

5.1. Light/dark shift of phototransduction proteins in transplant photoreceptors

Photoreceptors in retinal sheet transplants can display a perfect “normal” morphology; but can they respond to light?

S-antigen (arrestin) and rod transducin shift their position within the photoreceptors depending on the light cycle (Whelan and McGinnis, 1988); this process is disturbed in different retinal degeneration models (e.g., Peng et al., 2008). To test whether the phototransduction process is working in transplant photoreceptors, light-damaged rats with retinal sheet transplants were fixed either in light or at the end of dark cycle. The immunoreactivity of transplant photoreceptors for S-antigen (arrestin), α and γ-transducin, and rhodopsin was compared between dark- and light-adapted rats (Seiler et al., 1999).

Rhodopsin distribution was unchanged in light and dark adapted rats as expected. However, S-antigen shifted from outer (in the light) to inner segments (in the dark); α-transducin and γ-transducin shifted from inner (in the light) to outer segments (in the dark). Transducin immunoreactivity of transplant photoreceptors was considerably stronger in laminated than in disorganized transplant areas.

In summary, transplant photoreceptors can perform the phototransduction process similar to normal photoreceptors.

5.2. Transplant effect on visual behavior

Del Cerro et al. (del Cerro et al., 1991) used the indirect “startle reflex” to show that subretinal aggregate transplants had an effect on the vision of light-damaged recipients. This test warns rats with a light flash before exposing them to a loud noise. Rats with vision show less reaction to the noise because they have been pre-warned. Transplanted light-damaged rats showed a 20% less reaction (jumped 20% less) to the noise than non-transplanted light-damaged controls which was interpreted as a 20% restoration of vision. This paper created quite a stir when it was published; however it generated very skeptical responses from other vision scientists because it was only an indirect test to a simple light flash which did not involve any higher aspects of vision.

Kwan et al. used another indirect test of light-dark preference to show that the dark preference is restored after retinal transplantation (Kwan et al., 1999).

Another commonly used test, the pupillary light reflex (PLR), was established by Ray Lund and colleagues to show function of retinal transplants to the brain of newborn (Klassen and Lund, 1987) or adult recipients (Klassen and Lund, 1990; Radel et al., 1995), and was then later used to test photoreceptor sheet transplants (Silverman et al., 1992b), RPE transplants to RCS rats (Klassen et al., 2001) and photoreceptor precursors (MacLaren et al., 2006). In the MacLaren study (MacLaren et al., 2006), rho−/− mice with photoreceptor progenitor transplants showed 50% pupil constriction at about 0.6 log unit lower irradiance (ca. 13.5 log photons per s−1 cm−2) than sham injected rho−/− mice (ca. 14.1 log photons per s–1 cm–2). The increase in sensitivity to the sham-injected eye (max. 0.7 log units) correlated with the number of integrated photoreceptors. To put this into perspective: normal mice had 50% pupil constriction at ca. 10.8 log photons per s−1 cm−2, a 2.7 log difference. However, the PLR is an autonomous reflex and not related to the number of photoreceptors (Kovalevsky et al., 1995) and mediated by intrinsically photosensitive melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) in models of retinal degeneration (Semo et al., 2003) which normally receive synaptic inputs from rods and cones (Guler et al., 2008). Since the peak action spectrum of melanopsin ganglion cells is at 380 nm, it would be better to use blue and red light at lower light intensity. The PLR is very variable and depends on transplant location; many responses need to be averaged, and gas anesthesia should be used (Klassen et al., 2001). Thus, PLR testing has to be interpreted with caution and can only give some information about the function of transplants if contributions from melanopsin ganglion cells are eliminated, and appropriate controls are used.

Mice are normally active in the dark. The wheel running activity of normal mice in the dark is completely suppressed by exposure to light. Using this indirect test, Klassen et al. (Klassen et al., 2004b) showed that the running activity of rho−/− mice transplanted with cultured retinal progenitor cells was temporarily suppressed by exposing mice to different light levels at 8 weeks, but not 25 weeks after transplantation. Activity suppression of transplanted mice had a higher threshold than that of normal mice, but a lower threshold than non-transplanted rho−/− mice which only responded to the highest light intensity. This indicated that the transplantation of retinal progenitor cells restored some light sensitivity at 8 weeks after transplantation, but the effect had disappeared at 25 weeks.

The most widely used and accepted test of visual function is the optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) (McGill et al., 1988). Head tracking of experimental animals to moving stripes of varying widths shows thresholds of spatial frequency (discrimination of black and white stripes) and thus provides a measure of visual acuity. It can also be used to test contrast sensitivity (Thomas et al., 2010). It has been systematically used to investigate the progression of retinal degeneration (Thaung et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2010) and the efficacy of RPE and other cell transplants (Hetherington et al., 2000; McGill et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008b; Lu et al., 2010; Pearson et al., 2012).

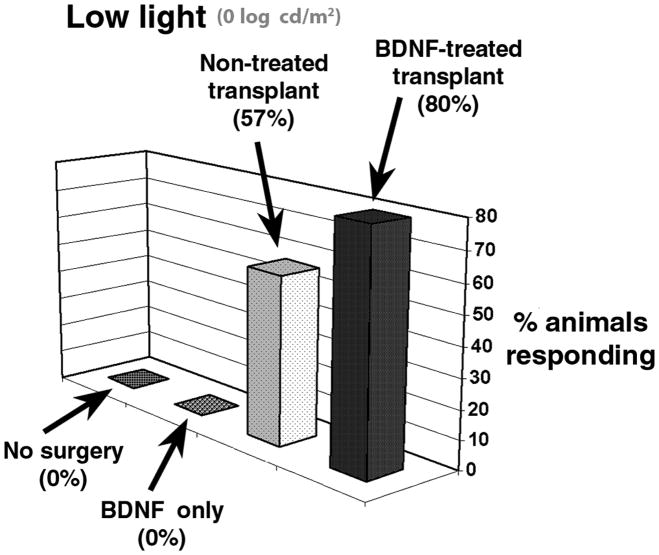

Our group modified the optokinetic drum to stimulate each eye separately and showed that retinal sheet transplants preserved visual acuity as determined by head tracking in S334ter-3 rats (Thomas et al., 2004a) and that BDNF microsphere treatment improves the functional effect of retinal sheet transplants (Seiler et al., 2008a) (see section 5.4).

The water maze test in which rats have to find a hidden platform indicated by visual cues, was used to demonstrate photoreceptor rescue in RCS rats by human fetal RPE transplants (Little et al., 1998), and to characterize the time course of degeneration in the RCS rat (McGill et al., 2004). After transplantation of NRL-GFP+ photoreceptor precursors to Gnat−/− mice that lack functional rods, 4 of 9 transplanted mice were able to find a hidden platform in dim light more than 70% of the time whereas sham surgery controls only found the platform by chance (50%) (Pearson et al., 2012). The performance in the water maze task was correlated to the number of integrated photoreceptors.

In summary, behavioral testing methods show variable reliability. Optokinetic testing is relatively good but not as sensitive to correlate with the quality of the transplant as the electrophysiological recording in the brain, but both methods complement each other.

5.3. Visual function of transplants shown by electrophysiology (Figure 3)

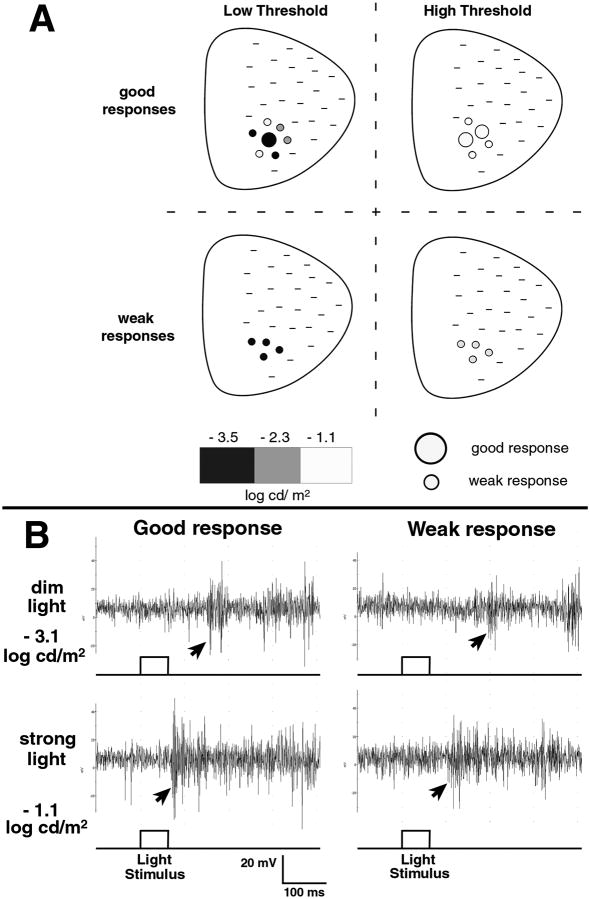

Figure 3. Brain recording after light stimulus to the eye showing the light sensitivity of transplants – electrophysiology in the superior colliculus (SC).

(A) Response characteristics in the SC from transplanted retinal-degenerate S334ter-3 rats using a 60 ms light stimulus (schematic diagram). Modified recording setup for obtaining rod-specific responses (Thomas et al., 2005). Response thresholds were determined by testing at different light intensities (−3.5 to −1 log cd/m2), indicated by black, gray, and white, from an area of the SC corresponding to the transplant location in the eye. Lower thresholds indicate higher light sensitivity and more rod involvement in the response. Examples of 4 different response types are presented.