Abstract

Background

Role of non-complement activating antibodies (Abs) to mismatched donor HLA in pathogenesis of chronic lung rejection is not known. We utilized a murine model of obliterative airway disease (OAD) induced by Abs to MHC class I and serum from donor specific Abs (DSA) developed human lung transplantation (LTx) recipients (LTxR) to test the role of non-complement activating Abs in development of OAD and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS).

Methods

Noncomplement activating anti-MHC (ncAbs) were administered intrabronchially in B.10 mice or in C3 knockout (C3KO) mice. Lungs were analyzed by histopathology. Lymphocytes secreting IL-17, IFN-γ or IL-10 to Collagen V (ColV) and K-alpha 1 tubulin (Kα1T) were enumerated by ELISpot. Serum Abs to ColV and Kα1T determined by ELISA. Cytokine and growth factor expression in lungs was determined by RTPCR. DSA from patients with BOS and control BOS-negative LTxR were analyzed by C1q assay.

Results

Administration of ncAbs in B.10 mice or C3KO resulted in OAD lesions. There were significant increases in IL-17 and IFNγ secreting cells to ColV and Kα1T along with serum Abs to these antigens. There was also augmented expression of MCP-1, IL-6, IL-1β, VEGF, TGFβ, and FGF in ncAbs administered mice by day 3. Among LTxR with BOS only 1/5 had C1q binding DSA.

Conclusion

Complement activation by Abs to MHC class I is not required for development of OAD and human BOS. Therefore, anti-MHC binding to epithelial and endothelial cells can directly activate pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory cascades leading to immune response to self-antigens and chronic rejection.

INTRODUCTION

Long-term lung allograft function is limited by chronic rejection diagnosed as bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) in lung transplant recipients (LTxR) (1, 2). The etiology of BOS is multifactorial, with significant contribution of immune responses to both allo and autoantigens (3, 4) and responses to mismatched donor HLA independently increase risk of BOS (4–6).

Towards understanding the role of antibodies (Abs) to major histocompatibility antigens (MHC) in pathogenesis of chronic rejection, we developed a murine model of obliterative airway disease (OAD) – correlate of BOS. In this model, Abs to MHC class I administered intrabronchially results in cellular infiltration and fibrosis around the terminal vessels and bronchioles, a hallmark of BOS (7). Additionally, there was C4d deposition and development of immune responses to lung specific self-antigens – collagenV (ColV) and k-alpha-1-tubulin (Kα1T) (7).

Anti-MHC can activate the complement cascade manifested as deposition of C4d and C3d (8) leading to development of tests that detected complement-activating donor specific Abs (DSA) (9, 10). Studies indicate complement fixing Abs (cfAbs) correlate with acute rejection, graft function and survival (10, 11). However, controversy exists for requirement of complement activation for rejection and graft loss since some reports did not find a correlation of cfAbs with rejection (12). Additionally, many patients with chronic rejection following heart or kidney transplants failed to demonstrate complement in grafts (C4d) even with DSA (13, 14).

We hypothesized that chronic rejection may develop even in the absence of complement activation. To this end we administered non-complement fixing MHC class I Abs (ncAbs) in wild type mice and in complement C3 knock out (C3KO) mice intrabronchially and tested their role in the development of OAD using the murine model OAD (7). In addition, we also tested BOS+ve and stable human LTxR for C1q binding DSA. We demonstrate that administration of ncAbs to MHC class I in wild type and C3KO mice results in OAD. This was associated with development of T-helper (Th)-17 immune responses to ColV and Kα1T and up-regulation of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors.

METHODS

Mice

Male C57BL/6 (H-2b), B10.A (H-2a), and complement factor C3-deficient C57BL/6 (C3KO) mice were utilized (6–8 weeks age, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Experiments were performed in compliance of the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University.

Monoclonal antibodies

Murine mAbs (BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) were tested endotoxin free. Abs against MHC class I were administered to following (n=10 each): 1) B10.A mice with ncAbs AF3-12.1.3 (IgG1, anti-H2-Kk) Abs; 2) C3KO mice with cfAbs AF6.88.5 (anti-H2Kb); 3) B10.A wild type mice with IgG1a isotype control Abs (MOPC-21); 4) C57BL/6 wild type mice with AF6.88.5 (anti-H2Kb) cfAbs. AF6.88.5 (IgG2a, anti-H2Kb) has been shown to be capable of activating complement and studies have shown that AF3-12,1,3 (IgG1a, anti-H2-Kk) cannot activate complement (15, 16).

Abs administration

Abs (200µg/dose) were administered intrabronchially in mice on days 1,2,3 and 6 and weekly thereafter as detailed previously (7).

Histology

Mice were sacrificed on day 15 and 30. Formaldehyde fixed lung sections were stained with Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome. Slides were analyzed by random sampling by two experts blinded to the experiments. Cellular infiltration and percentage fibrosis area were evaluated morphometrically in five randomly selected areas from 3 different parts of the lungs. Immunohistochemical staining was done to evaluate C4d and to enumerate CD4+ and CD8+ cells as described previously (7).

Enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) for cellular immune responses to ColV and Kα1T

To determine cellular immune responses to lung specific self-antigens ColV and Kα1T, we enumerated IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-17 secreting cells specific to ColV and Kα1T using ELISpot as described previously (7). Cells cultured in medium alone or with phytohemagglutinin were negative and positive controls respectively. Results were represented as mean spots per million cells (spm) ±SD.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Abs to ColV and Kα1T

Development of Abs to self-antigens ColV and Kα1T were determined using ELISA as described previously (7). Samples were considered positive if the value was over average cutoff values obtained from normal mouse sera. Concentration of Abs was calculated based on a standard curve of known concentration of anti-ColV Abs or anti-Kα1T (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Real-Time polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR) for cytokine and growth factor expression

To determine the gene expression profile of growth factors and cytokines that are up-regulated in lungs following administration of anti-MHC, expression of cytokines and growth factors in mouse lung tissue harvested on days 3, 5, 7 and 15 following Abs administration was analyzed using a cytokine and growth factor array (SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from 0.5 mg of lung using TRIzol (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO). RNA samples were quantified by absorbance at 260nm. RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA and RTPCR performed as per manufacturer’s instructions (SABiosciences).

Assessment of DSA and complement fixation by C1q assay in Human serum

To determine the role of Abs to mismatched donor HLA in human LTxR, we retrospectively analyzed serum from 5 patients who developed BOS following LTx and 11 stable patients. This was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University and samples obtained after informed consent.

Sera obtained 12 weeks post transplant were tested for DSA class I and II by Luminex single antigen beads (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA). These DSA+ve sera were then tested for complement binding by the C1q assay (One Lambda) as per manufacturer’s instructions (10).

Statistical Analysis

Morphometric analysis of tissue sections was performed on NIS-Elements Software (Nikon, Melville, NY) and images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse 55 microscope. Data was analyzed in SPSS v.19 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (LaJolla, CA) and represented at mean±SD with at least 5 mice in each cohort. ChiSquare tests or Student T-tests were used as appropriate. Significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Non-complement activating MHC-Class I Abs induces OAD

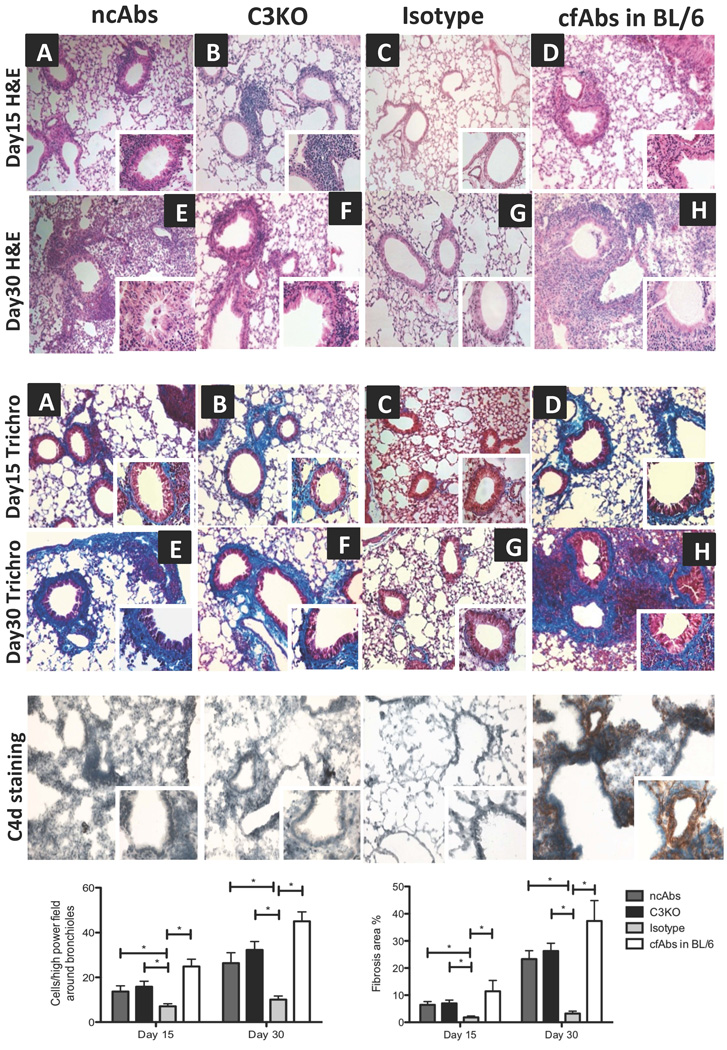

To determine the role of ncAbs to MHC class-I in development of OAD in B.10 mice we utilized a murine model of OAD (7). In mice IgG1 (AF3-12.1.3) Abs are incapable of activating complement (15). ncAbs (AF3-12.1.3) or isotype control Abs (MOPC-21) were administered intrabronchially in B.10 mice. cfAbs (IgG2a - AF6.88.5) administered in C57Bl/6 mice were positive control (15, 16). Histological analysis of the lungs on days 15 and 30 from all mice receiving ncAbs (n=10) demonstrated OAD with increased cellular infiltration around vessels and bronchioles and luminal occlusion and fibrosis (Figure 1). None of the isotype control mice had OAD.

Figure 1. Intrabronchial administration of Abs to MHC class I results in development of OAD in the absence of complement activation.

Histology of lungs harvested on day 15 (A-D) and day 30 (E-H) from ncAbs administered B.10 mice, cfAbs administered complement factor C3KO mice, isotype control Abs administered mice, or cfAbs administered C57BL/6 (BL/6) mice. Formalin fixed lung sections were stained with H&E or trichrome (trichro) stains. Collagen deposition seen as blue color on trichrome stains. Representative histology at 100x and 400x (insets) magnification with 5 mice in each cohort per time point all demonstrating similar histology.

Complement activation was determined in frozen sections of lungs stained for C4d deposition (C4d staining). Representative histology from lungs at day 30 from above cohorts of mice at 100x and 400x (insets) magnification.

Cellular infiltration was evaluated morphometrically on H&E stains as the number of mononuclear cells infiltrating bronchioles and vessels at five randomly chosen areas from 3 different areas of the lungs. These were represented as mean±standard deviation (SD) per high power field (400x). Percentage of fibrosis was determined morphometrically in trichrome stains (with blue collagen staining) as the total area enclosed by basement membrane at 5 different high power (400x) field and dividing by a factor of 5 in 3 different areas of the lungs, represented as mean ±SD percent of fibrosis area.

All images in figure 1 were obtained on a Nikon Eclipse 55i microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and analyzed morphometrically on NIS-Elements BR morphometric software (Nikon).

Immunohistochemical staining revealed complete absence of C4d in lung parenchyma especially around vessels and bronchioles in ncAbs administered mice. Mice administered cfAbs demonstrated complement deposition (Figure 1), (7).

Complement fixing MHC class I Abs induces OAD in C3KO mice

To confirm that complement activation is not necessary for pathogenesis of OAD, C3 deficient mice (C3KO) were administered complement-activating Abs to MHC class I (IgG2a AF6.88.5) (15, 16). Anti-MHC class I administration in C3KO mice resulted in OAD with cellular infiltration around vessels and bronchioles and fibrosis (Figure 1). As expected, OAD lesions in C3KO mice did not demonstrate C4d (Figure 1).

These results confirm that development of OAD by anti-MHC can take place in absence of complement activation. However, it is worth noting that OAD lesions seen following administration of either ncAbs to MHC or cfAbs to C3KO animals are less severe than those seen with cfAbs in wildtype mice (Figure 1).

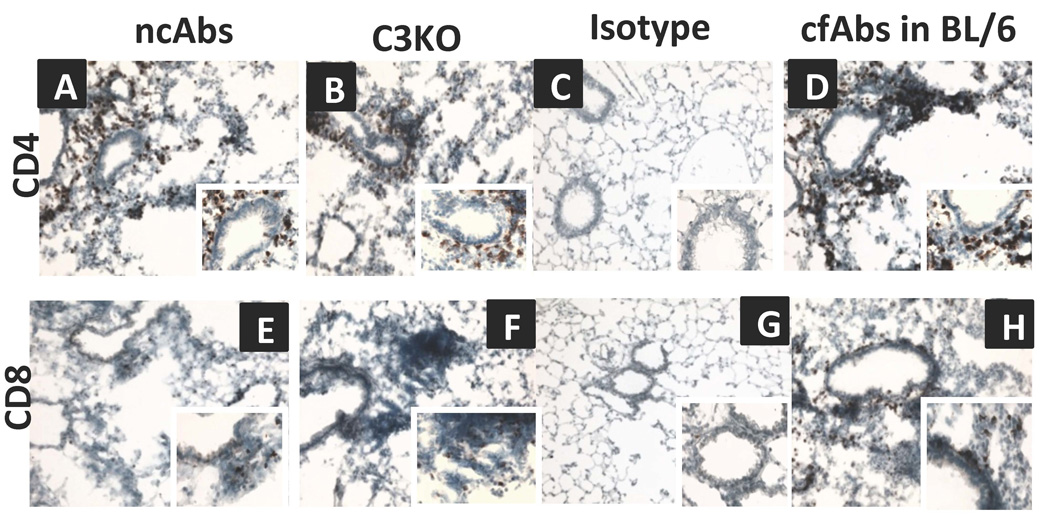

Cellular infiltration in lungs following administration of anti-MHC in absence of complement activation

Since administration of ncAbs resulted in OAD lesions with significant cellular infiltration (27±5 cells/hpf, Figure 1), the phenotype of infiltrating cells was determined by immunohistochemical staining. As shown in figure 2 there was increased infiltration of CD4+ cells around the bronchioles and vessels in ncAbs administered mice as compared to isotype control mice (cells/high power field (hpf) − 25±9 vs. 3±2 p<0.05). There was also an increase in infiltration of CD8+ cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Abs to MHC class I induce infiltration of CD4 and CD8 T-cells in the lungs in the absence of complement activation.

Histology of lungs harvested on day 30 from ncAbs administered B.10 mice, cfAbs administered complement factor C3KO mice, isotype control Abs administered mice, or cfAbs administered C57BL/6 (BL/6) mice. Frozen sections were stained for CD4+ (A-D) and CD8+ cells (E-H) and representative histology shown at 100x and 400x (insets) magnification. Positive cells (staining brown) were enumerated morphometrically using NIS-Element BR software. CD4 cells/high-power field − 25±9 vs. 30±12 vs. 3±2 vs. 40±5, p<0.05, CD8 cells/high power field − 10±4 vs. 15±7 vs. 3±2 vs. 23±6. p<0.05 in the cohorts respectively.

We also analyzed lungs from cfAbs treated C3KO mice and significant increase in CD4+ cells (30±12 cells/hpf) and CD8+ cells (15±7 cells/hpf) were noted. This indicates that anti-MHC class I induces infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells without complement activation.

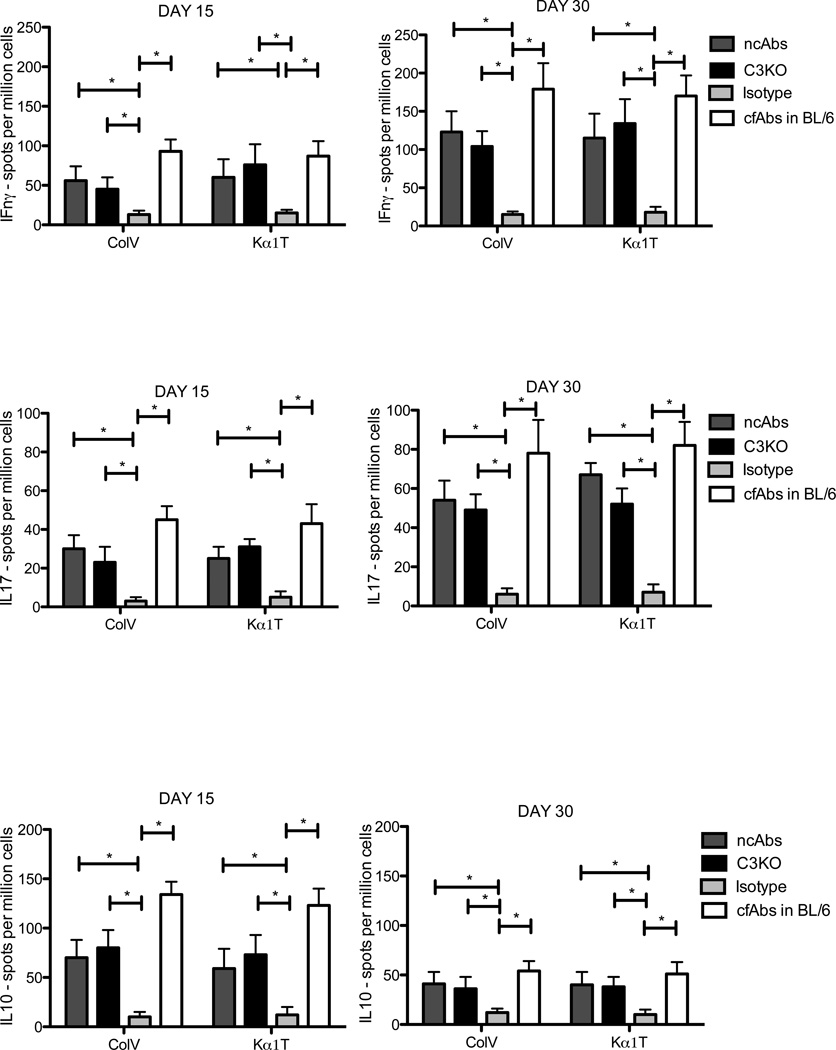

Induction of self-antigens specific IFN-γ, and IL-17 secreting cells and suppression of IL-10 cells following administration of ncAbs

To investigate development of immune responses to ColV and Kα1T, splenocytes were isolated and were stimulated with ColV and Kα1T and IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-17 secreting cells were enumerated using ELISpot. By day 15, there was a significant increase in cells secreting IL-17 specific to ColV and Kα1T in ncAbs administered mice that was further increased by day 30 compared to isotype control mice (Figure 3; in spm±SD: Day 30 ColV 54±10 6±3, p=0.02; Kα1T − 67±6 vs. 7±4, p=0.03). There was also an increase in IFN-γ secreting cells in response to ColV and Kα1T in ncAbs administered mice, which was significantly higher by day 30 (p<0.05, Figure 3). IL-10 specific responses were significantly reduced at day 30 in comparison to Day 15 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Induction of IL-17 and IFN-γ responses and suppression of IL-10 responses to self-antigens – ColV and Kα1T following intrabronchial administration of anti-MHC class I without activation of complement.

Splenocytes isolated on days 15 and 30 from ncAbs administered B.10 mice (dark grey bars), cfAbs administered complement factor C3KO mice (black bars), isotype control Abs administered mice (light grey bars), or cfAbs administered C57BL/6 (BL/6) mice (white bars) were stimulated with ColV and Kα1T and IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-10 secreting cells were enumerated by ELISpot. All cells cultured in positive control antigen phytohemagglutinin demonstrated IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-17 responses (not shown in figure). Data represented as mean ±SD spots per million cells of 5 different mice. * indicates p<0.05.

Further, in cfAbs C3KO mice, a similar induction of self-antigen specific cellular responses was seen with increase in IL-17, and IFN-γ secreting cells (IL-17 – ColV . 48±8 spm, Kα1T − 52±8, Figure 3).

These results indicate that even in absence of complement activation, anti-MHC class I can induce immune responses to self-antigens similar to that following administration of cfAbs to MHC class (Figure 3) (7) with a predominant IL-17 and IFN-γ response to ColV and Kα1T.

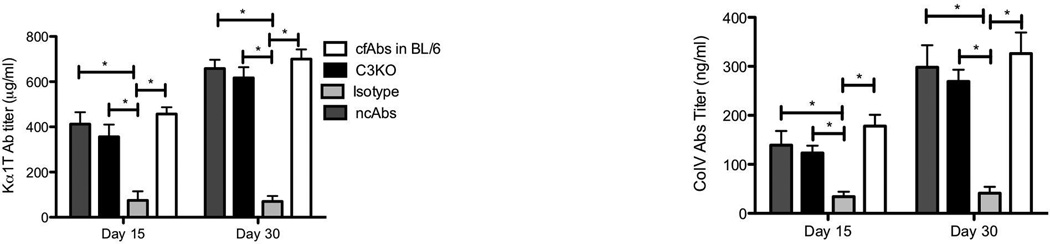

Complement activation by Abs to MHC class I is not required for the development of Abs against lung-associated self-antigens ColV and Kα1T

To determine the role of ncAbs in development of humoral responses to self-antigens (ColV and Kα1T), serum from Abs administered mice were tested for Abs to ColV and Kα1T by ELISA. B.10 mice administered ncAbs demonstrated significant increase in serum Abs to ColV and Kα1T by day 15 compared to isotype control mice (in µg/ml ColV − 139±29 vs. 34±10, p<0.002, Kα1T − 412±53 vs. 75±40, p=0.001, Figure 4) and these titres were elevated by day 30. C3KO mice also developed Abs to ColV (123±15) and Kα1T (356±46) by day 15, which increased by day 30 (Figure 4). cfAbs in wild type C57Bl/6 mice resulted in higher titers of Abs to self-antigens (Figure 4). These results demonstrate that administration of ncAbs results in development of both cellular and humoral immune responses to self-antigens.

Figure 4. Development of serum Abs to ColV and Kα1T after administration of Abs to MHC class I in absence of complement activation.

Serum collected on days 15 and 30 from ncAbs administered B.10 mice (dark grey bars), cfAbs administered complement factor C3KO mice (black bars), isotype control Abs administered mice (light grey bars), or cfAbs administered C57BL/6 (BL/6) mice (white bars) were tested for development of Abs to ColV and Kα1T by ELISA. Data represented as Abs concentration in ng/mL as mean±SD of 5 different mice. * indicates p<0.05

Up-regulation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic growth factors in lungs by ncAbs to MHC class I

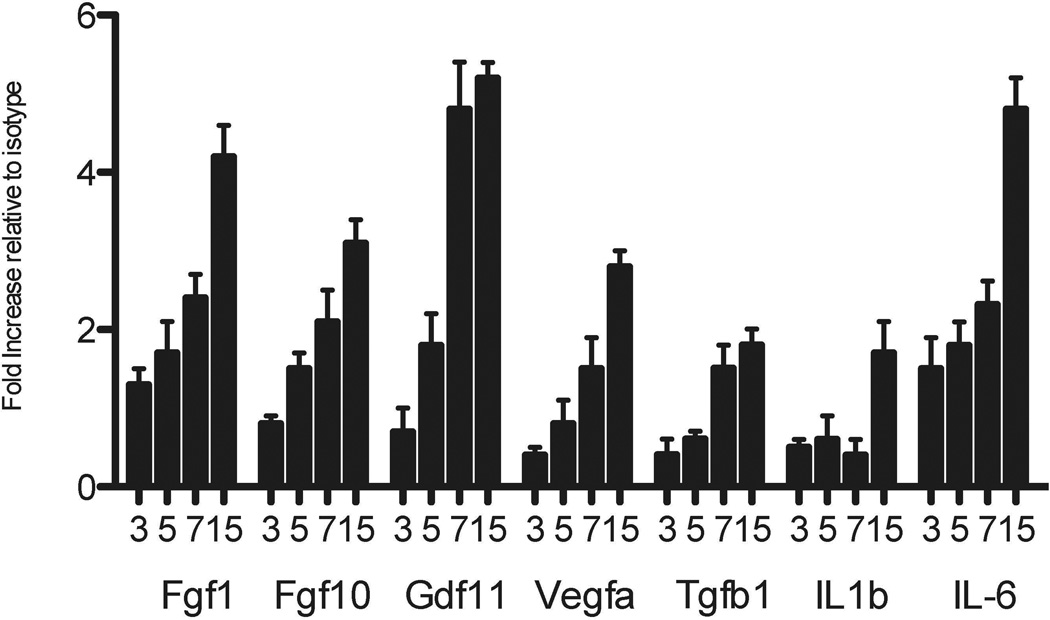

To elucidate the mechanisms by which ncAbs can induce OAD, expression of growth factors and cytokines was determined in lungs. In comparison to isotype control mice, administration of ncAbs to MHC class I resulted in significant up-regulation of fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1 – day 15 4.2±0.4 fold, p<0.05), fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10 – 4.8±0.4 fold, p<0.05), granulocyte derived factor (GDF – 3.1±0.3 fold, p<0.05), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF – 5.2±0.5 fold, p<0.05), transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1 – 2.8±0.3 fold, p<0.05) (Figure 5). There was also up-regulation of IL1β (1.8±0.2 fold, p=0.05), IL-6 (1.7±0.04 fold, p=0.049), macrophage chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1 – 4.5±1.2 fold, p=0.03) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα – 3.8±0.9 fold, p=0.04). The expression of other cytokines and growth factors analyzed were similar in ncAbs and isotype treated mice (data not shown).

Figure 5. Upregulation of growth factors and inflammatory cytokine and chemokines in lungs of mice administered non-complement activating Abs to MHC class I.

Lungs were harvested on days 3, 5, 7, 15 from ncAbs to MHC class I administered B.10 mice or isotype control Abs administered mice. Total RNA was extracted from lung and converted to cDNA. Expression of growth factors, cytokines and chemokines was determined using RTPCR using a murine cytokine and growth factor array. Fgf – Fibroblast growth factor, GDF – granulocyte derived factor, Vegfa – Vascular endothelial growth factor alpha, Tgfb – Transforming growth factor beta. Data represented as mean±SD fold difference of expression in ncAbs treated mice compared to isotype.

Lack of complement binding by DSA developed in BOS LTx patients

As ncAbs to MHC class I induced OAD, we investigated the role of complement fixing DSA in human LTxR with BOS. Five BOS+ve LTxR and 11 stable (free of BOS pathology) LTxR were retrospectively analyzed for DSA 12 weeks post-LTx. All 5 BOS patients had class I DSA (Table 1). Amongst these only 1 patient had DSA that bound to C1q as detected by the Luminex based C1q assay. Among stable patients 3 out of 11 had C1q binding DSA. This preliminary analysis suggests that although BOS patients develop DSA most of these Abs are not complement fixing, implicating a role for non-complement activating DSA in pathogenesis of BOS.

Table 1.

DSA developed in patients with BOS following LTx predominantly are not complement fixing (C1q binding).

| C1q+ve DSA | Time post-LTx | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOS + ve LTxR (n=5)* | 1 (20%) | 12 weeks | Not significant |

| Stable (no BOS) (n=11)* | 3 (27%) | 12 weeks |

All BOS+ve and stable LTxR were DSA+ve as determined by Luminex single antigen beads (One Lambda). C1q binding was tested by the C1q binding assay (One Lambda).

DISCUSSION

Chronic rejection is the major cause for long-term morbidity and late graft loss especially in lung allografts (17, 18). Abs against mismatched donor MHC antigens have been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis of chronic rejection (7, 17). Alloimmune Abs bind to epithelial and endothelial cells and activate complement cascade resulting in deposition of C4d and organ damage, which is a hallmark of the acute rejection (19). However, chronic rejection is not always associated with C4d (13, 16) thereby questioning the importance of complement activation in its immunopathogenesis. In this report we utilize a murine model of OAD (a correlate of BOS) with intrabronchial Abs administration to test the hypothesis that allo-immune responses can induce chronic rejection pathology in the absence of complement. This study provides evidence that ncAbs to MHC class I can induce development of OAD in mice (Figure 1) with up-regulation of profibrotic growth factors and inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. Further, there was development of IL-17 type autoimmune response to self-antigens ColV and Kα1T. Additionally preliminary analysis of BOS+ve human LTxR demonstrated low prevalence of complement fixing DSA.

Complement activation has been implicated in pathogenesis of acute rejection (20). In early studies, rejection developed only with passive transfer of complement fixing Abs (21) and ncAbs were not capable to inducing rejection on their own but could potentiate the effect of cfAbs (16). However recognition of clinical rejection in absence of complement activation (C4d/ C3d staining) has questioned its role (13) both for acute and more importantly for chronic rejection. De novo development of DSA in human LTx have been strongly correlated with the development of BOS suggesting a role for DSA in the immunopathogenesis of BOS (3). Further, DSA often precedes BOS by several months (3). However, results from a small cohort (table 1), suggest that these DSA need not be complement fixing.

Murine OAD is a correlate of chronic rejection (clinically diagnosed as BOS) following human LTx. OAD and human BOS both have similar pathology – obliteration of the terminal airways and vessels, hence suggesting that the mouse model is useful to define the immunopathogenesis of human BOS. Although this is a non-transplant model with no actual “rejection”, the results presented in this report using this model of murine OAD, and preliminary data from human BOS patients suggest that complement activation is not essential for the immunopathogenesis of BOS induced by alloAbs. This is further supported by previous reports of allo-Abs induced transplant arteriopathy and endarteritis in murine heart allografts in the absence of complement activation (14). To further confirm this and to rule out the possibility of low levels of complement activation with ncAbs, we utilized complement deficient C3KO mice. The development of OAD by anti-MHC in C3KO further substantiates that activation of complement is not essential.

Anti-MHC can bind to antigens on endothelial and epithelial cells leading to activation and phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt (22). This has been further postulated to promote sustained endothelial cell proliferation (22, 23). In addition, these alloAbs also activate endothelial cells to secrete FGF and VEGF (23). Endothelial cells co-cultured with macrophages in the presence of IgG1 type allo-Abs (ncAbs) has been shown to result in up-regulation of IL-6 and MCP-1 (24). The significant up-regulation of VEGF, TGF-β, MCP-1 and IL-6 seen in the lungs of mice administered ncAbs as early as day 3 (Figure 5), further supports the hypothesis that alloAbs may directly contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic rejection without complement activation.

The up-regulation of IL-6, IL-1β and TGF-β seen in the ncAbs administered mice has an important bearing on IL-17 type autoimmune responses to self-antigens. An increase in MCP1 and evidence for macrophages and epithelial cells to secrete IL-6 upon ligation with ncAbs in invitro studies (24) further supports our finding of increased expression of these cytokines in the lungs. IL-6 and IL-1β further supports differentiation of Th17 cells.

Studies from our laboratory as well as others have implicated an important role for IL-17 responses to self-antigens ColV and Kα1T in the pathogenesis of BOS (7, 25–27). Thus cellular and humoral autoimmune response to ColV and Kα1T in the ncAbs treated and C3KO mice, supports the hypothesis, that anti-MHC class I can activate profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines that favor the development of IL-17 response to self-antigens leading to OAD.

It is also important to note that in cfAbs administered C56BL/6 mice, OAD lesions and autoimmune responses were more apparent than in ncAbs, C3KO mice (Figure 1, 3, 4). Complement factors C3a and C5a can directly co-stimulate CD4 T cells leading to proliferation even in absence CD40 (28). C3 also promotes clonal antigen specific expansion of CD4 and CD8 Tcells, suggesting an important role for complement in T-cell immune responses (29–31). Additionally, ncAbs can synergize and augment the effect of even low titers of cfAbs that can result in chronic rejection (16). Therefore, in human LTx it is likely that ncAbs may synergize with low titers of cfAbs in augmenting chronic rejection.

Being a non-transplant model, this model is limited in simulating the clinical LTx and BOS. Murine LTx thus far don’t have highly reproducible development of chronic rejection (26, 32, 33). However in our model of intrabronchial anti-MHC administration almost universally results in OAD by day 30, which is similar to pathology of BOS supporting the utilization of this model and the extrapolation of the results to understand the pathogenesis of chronic human lung allograft rejection (7). Also further studies are required to delineate the role of ncAbs in BOS.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that ncAbs to MHC class I can induce murine OAD that is similar to chronic rejection pathology in human BOS. An increase in profibrotic cytokines and growth factors suggests that anti-MHC can directly activate profibrotic cascades that favor the development of Th17 immune response to self-antigens resulting in development of OAD. Based on the results of anti-MHC induced murine OAD as well as preliminary results from human BOS+ve LTxR sera, we conclude that complement activation is not obligatory for the development of BOS following human LTx.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI/NIAID HL092514-01A2, HL056643 and the BJC Foundation (TM). The authors would like to thank Ms. Billie Glasscock for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burton CM, Carlsen J, Mortensen J, Andersen CB, Milman N, Iversen M. Long-term survival after lung transplantation depends on development and severity of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hachem RR, Trulock EP. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: pathogenesis and management. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;16:350–355. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saini D, Weber J, Ramachandran S, et al. Alloimmunity-induced autoimmunity as a potential mechanism in the pathogenesis of chronic rejection of human lung allografts. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.01.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaresan S, Mohanakumar T, Smith MA, et al. HLA-A locus mismatches and development of antibodies to HLA after lung transplantation correlate with the development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Transplantation. 1998;65:648–653. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199803150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MA, Sundaresan S, Mohanakumar T, et al. Effect of development of antibodies to HLA and cytomegalovirus mismatch on lung transplantation survival and development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:812–820. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)00444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer SM, Davis RD, Hadjiliadis D, et al. Development of an antibody specific to major histocompatibility antigens detectable by flow cytometry after lung transplant is associated with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Transplantation. 2002;74:799–804. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukami N, Ramachandran S, Saini D, et al. Antibodies to MHC class I induce autoimmunity: role in the pathogenesis of chronic rejection. J Immunol. 2009;182:309–318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan SC. Complement fixing donor-specific antibodies and allograft loss. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahrmann M, Exner M, Regele H, et al. Flow cytometry based detection of HLA alloantibody mediated classical complement activation. J Immunol Methods. 2003;275:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yabu JM, Higgins JP, Chen G, Sequeira F, Busque S, Tyan DB. C1q-fixing human leukocyte antigen antibodies are specific for predicting transplant glomerulopathy and late graft failure after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:342–347. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318203fd26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutherland SM, Chen G, Sequeira FA, Lou CD, Alexander SR, Tyan DB. Complement-fixing donor-specific antibodies identified by a novel C1q assay are associated with allograft loss. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honger G, Wahrmann M, Amico P, Hopfer H, Bohmig GA, Schaub S. C4d-fixing capability of low-level donor-specific HLA antibodies is not predictive for early antibody-mediated rejection. Transplantation. 2010;89:1471–1475. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181dc13e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas M. C4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection in renal allografts: evidence for its existence and effect on graft survival. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75:271–278. doi: 10.5414/cnp75271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirohashi T, Uehara S, Chase CM, et al. Complement independent antibody-mediated endarteritis and transplant arteriopathy in mice. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ey PL, Russell-Jones GJ, Jenkin CR. Isotypes of mouse IgG--I. Evidence for 'non-complement-fixing' IgG1 antibodies and characterization of their capacity to interfere with IgG2 sensitization of target red blood cells for lysis by complement. Mol Immunol. 1980;17:699–710. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(80)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahimi S, Qian Z, Layton J, Fox-Talbot K, Baldwin WM, 3rd, Wasowska BA. Non-complement-and complement-activating antibodies synergize to cause rejection of cardiac allografts. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:326–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seetharam A, Tiriveedhi V, Mohanakumar T. Alloimmunity and autoimmunity in chronic rejection. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:531–536. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833b31f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hachem RR, Yusen RD, Meyers BF, et al. Anti-human leukocyte antigen antibodies and preemptive antibody-directed therapy after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin WM, 3rd, Kasper EK, Zachary AA, Wasowska BA, Rodriguez ER. Beyond C4d: other complement-related diagnostic approaches to antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platt JL, Saadi S. The role of complement in transplantation. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:965–971. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasowska BA, Qian Z, Cangello DL, et al. Passive transfer of alloantibodies restores acute cardiac rejection in IgKO mice. Transplantation. 2001;71:727–736. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin YP, Jindra PT, Gong KW, Lepin EJ, Reed EF. Anti-HLA class I antibodies activate endothelial cells and promote chronic rejection. Transplantation. 2005;79:S19–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153293.39132.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaramillo A, Smith CR, Maruyama T, Zhang L, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T. Anti-HLA class I antibody binding to airway epithelial cells induces production of fibrogenic growth factors and apoptotic cell death: a possible mechanism for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CY, Lotfi-Emran S, Erdinc M, et al. The involvement of FcR mechanisms in antibody-mediated rejection. Transplantation. 2007;84:1324–1334. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000287457.54761.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwata T, Philipovskiy A, Fisher AJ, et al. Anti-type V collagen humoral immunity in lung transplant primary graft dysfunction. J Immunol. 2008;181:5738–5747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan L, Benson HL, Vittal R, et al. Neutralizing IL-17 prevents obliterative bronchiolitis in murine orthotopic lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:911–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bharat A, Saini D, Steward N, et al. Antibodies to self-antigens predispose to primary lung allograft dysfunction and chronic rejection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strainic MG, Liu J, Huang D, et al. Locally produced complement fragments C5a and C3a provide both costimulatory and survival signals to naive CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2008;28:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dempsey PW, Allison ME, Akkaraju S, Goodnow CC, Fearon DT. C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science. 1996;271:348–350. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama Y, Kim SI, Kim EH, Lambris JD, Sandor M, Suresh M. C3 promotes expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in a Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:2921–2931. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemper C, Chan AC, Green JM, Brett KA, Murphy KM, Atkinson JP. Activation of human CD4+ cells with CD3 and CD46 induces a T-regulatory cell 1 phenotype. Nature. 2003;421:388–392. doi: 10.1038/nature01315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Vleeschauwer S, Jungraithmayr W, Wauters S, et al. Chronic rejection pathology after orthotopic lung transplantation in mice: the development of a murine BOS model and its drawbacks. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krupnick AS, Lin X, Li W, et al. Orthotopic mouse lung transplantation as experimental methodology to study transplant and tumor biology. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:86–93. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]