Abstract

Prevention of adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction (MI) remains a therapeutic challenge. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) are a well-established first-line treatment. ACE-I delay fibrosis, but little is known about their molecular effects on cardiomyocytes. We investigated the effects of the ACE-I delapril on cardiomyocytes in a mouse model of heart failure (HF) after MI. Mice were randomly assigned to three groups: Sham, MI, and MI-D (6 weeks of treatment with a non-hypotensive dose of delapril started 24h after MI). Echocardiography and pressure-volume loops revealed that MI induced hypertrophy and dilatation, and altered both contraction and relaxation of the left ventricle. At the cellular level, MI cardiomyocytes exhibited reduced contraction, slowed relaxation, increased diastolic Ca2+ levels, decreased Ca2+-transient amplitude, and diminished Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments. In MI-D mice, however, both mortality and cardiac remodeling were decreased when compared to non-treated MI mice. Delapril maintained cardiomyocyte contraction and relaxation, prevented diastolic Ca2+ overload and retained the normal Ca2+ sensitivity of contractile proteins. Delapril maintained SERCA2a activity through normalization of P-PLB/PLB (for both Ser16-PLB and Thr17-PLB) and PLB/SERCA2a ratios in cardiomyocytes, favoring normal reuptake of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. In addition, delapril prevented defective cTnI function by normalizing the expression of PKC, enhanced in MI mice. In conclusion, early therapy with delapril after MI preserved the normal contraction/relaxation cycle of surviving cardiomyocytes with multiple direct effects on key intracellular mechanisms contributing to preserve cardiac function.

Keywords: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors; pharmacology; therapeutic use; Animals; Calcium; metabolism; Diastole; Disease Models, Animal; Excitation Contraction Coupling; drug effects; Male; Mice; Myocardial Contraction; drug effects; Myocardial Infarction; drug therapy; metabolism; mortality; Myofibrils; metabolism; Ryanodine Receptor Calcium Release Channel; metabolism; Sarcoplasmic Reticulum; metabolism; Ventricular Remodeling; drug effects

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, excitation-contraction coupling, heart failure, hypertrophy, myofilaments, sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

INTRODUCTION

Over-activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a critical role in the progression of cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction (MI) [1]. Evidences for the cardiovascular benefits of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) have emerged from long-term studies (CONSENSUS, SAVE, AIRE, TRACE, SOLVD) [2]. Indeed, ACE-I lower mortality rates and hospital admissions in patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and progressive heart failure (HF) [3]. Benefits occur mainly via blood pressure reduction, yet there is evidence of blood pressure independent protective effects in coronary disease ([4]. Experimental studies have shown that ACE-I therapy delays myocardial remodeling, thus inhibiting the transition to HF [5–7]. At the clinical level, short-term studies (e.g., CONSENSUS-II, AIRE) suggest that early ACE-I therapy provides significant and rapid benefits [2]. Long-term therapy attenuates morphological and functional alterations related to hypertrophy and fibrosis [8, 9]. In particular, ACE-I therapy blocks the fibrogenic action of angiotensin both in experimental models and in patients. However, the pure anti-remodeling effects of ACE-I through normalization (or prevention) of impaired intracellular Ca2+ signaling and excitation-contraction coupling as observed in HF (i.e. independent of the blood pressure reduction) at the molecular level have been poorly explored.

After MI, the sustained activation of compensatory neurohormonal systems, coupled with the alteration of various cell signaling and gene expression pathways, triggers a domino effect that leads to severely compromised cardiac function. Changes in cardiomyocyte phenotype are responsible for significant alterations in excitation-contraction (E–C) coupling and pro-arrhythmogenicity, due to the modification of cellular ion currents and Ca2+ handling [10–12]. Specific therapeutic options to optimize healing and prevent adverse post-MI remodeling are currently lacking [13]. Several studies have shown that ACE-I modify the expression of genes coding for Ca2+ handling proteins during HF [14–16] but the functional consequences are not well-established. In addition, no study has evaluated the effects of ACE inhibition on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, a key determinant of contraction, during HF.

The ACE-I delapril is an old molecule but still currently used, in combination with Ca2+ antagonist manidipine, as a therapeutic option to control hypertension complicated by diabetes and microalbuminuria, and to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in high-risk patients [17]. Interestingly, all ACE-I do not have exactly the same molecular effects and pharmacological properties. The affinities of the enzymatic carboxyterminal and aminoterminal regions (C-site and N-site) of ACE for ACE-I drugs differ according to the organ involved and the two catalytic sites may control different functions [18, 19]. Delaprilat, the active metabolite of delapril, binds with higher affinity to the C-site than to the N-site, in particular in the left ventricle (LV) and reduces cardiac hypertrophy [20]. By comparison, the ACE-I captopril displays a high affinity for the N-site and has less affinity for the myocardium [18, 19]. In the present work, we focused on the independent blood pressure effects of a chronic treatment with delapril, started 24 hours after MI in mice, on surviving LV cardiomyocytes. The study focused on the molecular effects of delapril not only on Ca2+ handling but also on Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments which, to our best knowledge, has never been studied before. Delapril preserved the contractile properties of cardiomyocytes by reducing the Ca2+ transient alterations and by preventing the alterations of myofilament contractile properties in HF after MI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MI model and experimental groups

Experimental protocols were approved by the institutional standing committee for animal research and conformed to European directives (86/609/CEE) and the standards set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (published by the National Academy of Science, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.). Male Swiss mice (Janvier, France), aged 8 weeks and weighing 34.5±1.5 g (n=102) were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups: Sham-operated (Sham), subjected to MI, or subjected to MI and treated with delapril (MI-D). MI was induced by left coronary artery ligation [21]. Briefly, a left thoracotomy was performed in anesthetized mice (2% inhaled isoflurane in O2, Aerrane®, Baxter, France). The artery was ligated 1–2 mm beyond the point of emergence from the top of the left atrium, using an 8-0 Sofsilk suture (Syneture, USA). A unique subcutaneous injection of 0.01 ml buprenorphine solution (0.3 mg.ml−1) for postoperative analgesia was administered. Sham animals were subjected to the same surgical procedure but without coronary artery ligation. The MI-D group received a daily dose of 6 mg.kg−1 of delapril (kindly supplied by Chiesi Farmaceutici, Parma, Italy) provided in drinking water, starting 24 hours after surgery and lasting for 6 weeks. This dose was chosen because delapril given for 3 weeks did not lower BP in conscious PMI rats [22]. A complete morphological and functional cardiac evaluation was performed at this stage as described [23] before cellular and molecular studies.

Echocardiography

Longitudinal transthoracic echocardiography was carried out in awake mice using a sonographic apparatus equipped with an i13L 14 MHz linear array transducer designed for the examination of small rodents (Vivid 7, GE Medical systems, USA). Mice were trained for several days before the examination in order to decrease the stress due to handling. No difference in heart rate (bpm) was observed within the 3 groups (701±10, 702±10, 715±11, in Sham, Mi and MI-D respectively). Only mice with a large infarct and an atrial diameter of more than 1.9 mm were used to ensure the transition to HF.

Pressure-volume (P-V) analysis

Briefly, a 1F dual-field combination pressure-conductance catheter (model PVR-1045, Millar Instruments) connected to a pressure-conductance unit (MPVS-300, Millar) was inserted in the right carotid artery and advanced into the LV of anesthetized mice (isoflurane 1.5–2%). Changes in LV function were visualized through the use of ventricular pressure-volume (P-V) loops. Measurements were acquired at rest and after dobutamine infusion (5 μg.kg−1.min−1). Steady-state LV pressure levels were determined during suspended ventilation, and signal-averaged data from 5–10 consecutive beats were used. Parallel conductance from surrounding structures was calculated by injecting a 10 μL bolus of 15% NaCl through the femoral vein. Load-independent parameters of contractility were derived from the P-V relationship as described [24]. The mean arterial pressure and the maximal (+dP/dt) and minimal (−dP/dt) first derivatives of LV pressure were calculated with IOX v1.8.9.4 software (EMKA Technologies, France).

Quantification of fibrosis

Interstitial fibrosis was measured in 10 μm thick transverse sections of mouse hearts in the peri-infarcted area [25] to assess the effect of delapril on this parameter. Briefly, after cervical dislocation, hearts were excised from mice, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Collagen distribution was determined using picrosirius red-stained sections and expressed as a percentage of total LV surface area (Histolab, Gothenburg, Sweden).

Cell Contractility and Ca2+-Transient Measurements

LV myocytes were freshly isolated from the non-infarcted free wall and recorded as previously described [26]. For measurements of intracellular Ca2+, confocal images were obtained by line scanning (1.5 ms/line) cells loaded with fluo-4-AM (4 μmol/L) [26]. The time course of Ca2+ transients was assessed by measuring the time constant (τ) of the exponential part of the decay phase. Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ content was assessed by measuring the peak amplitude of the cytosolic Ca2+ transient induced by the rapid application of caffeine (10 mmol/L). Sarcomere length (SL) and fluorescence (405 and 480 nm) were also simultaneously recorded using an IonOptix system (Milton, MA) and used specifically for the measurement of diastolic Ca2+. To do this, LV myocytes were incubated for 30 min with indo-1 AM (10 μmol/L Invitrogen inc. France) as previously described [27]. Cells were field stimulated to contract at 1 Hz. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Force Measurements in Permeabilized Cardiomyocytes

Isometric force was measured in single permeabilized cardiomyocytes at different Ca2+ concentrations at an SL of 1.9 μm as described [27]. Force was normalized to the cross-sectional area measured from imaged cross-sections, and the force-pCa relation fitted to a Hill equation. In some experiments, myofilaments have been incubated with the catalytic domain of PKA (100 U/mL; Sigma-aldrich, Paris, France) or PKC (0.25 U/mL; Sigma) for 50 min at room temperature.

Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated and analyzed using standard methods. Tissue from the non-infarcted free wall of LV was dissected (n=6 in each group) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Gene expression levels were determined by RT-PCR (LightCycler, Roche, Meylan, France). The sequences of the specific primers for collagen I and collagen III were: Collagen I 5′-TGGTACATCAGCCCGAAC-3′ (sense), and 5′-GTCAGCTGGATAGCGACA-3′ (antisense); collagen III 5′-GACAGATTCTGGTGCAGAGA-3′ (sense), and 5′-CATCAACGACATCTTCAGGAAT-3′(antisense). Results are expressed as a function of β-tubulin expression level.

Protein Analysis

Ca2+ handling

Proteins extracted from the non-infarcted free wall of the LV were separated using 2–20 % SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Protran, Schleichen and Schuele, Dassel, Germany). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-RyR2 (Affinity Bioreagents, Neshanic Station, NJ), NCX antibody (R3F1, SWANT, Switzerland), Phospho Ser2809-RyR2 antibody (A010-30, Badrilla, Leeds, UK), SERCA2a antibody (A010-20, Badrilla, UK), Ser16-PLB and Thr17-PLB and PLB antibody (Badrilla, UK). RyR2, SERCA2a and PLB levels were expressed relative to GAPDH (Chemicon International, CA, USA) on the same membrane. Immunodetection was carried out using the ECL Plus system (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont Buckinghamshire, UK).

Myofilament proteins

Myofibrillar proteins were analyzed in skinned muscle strips from the non infarcted area of the LV. The heart was pre-skinned by perfusion with a relaxing solution containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors, for 10 min. Phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of myosin light chain 2 (MLC-2) were separated on a 10% urea gel and detected with an antibody specific to cardiac MLC-2 (Coger SA, Paris, France). TnI and PKC-α was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and membranes were incubated with specific antibodies against total cardiac TnI (Cat#4T21, Hytest, Turku, Finland), the PKA-phosphorylated form of cardiac TnI (Cat#4T45, Hytest), PKC-α ((Upstate, Biotechnology, Milton Keynes, UK) or the phospho-Ser657 PKCα (Santacruz, Heidelberg, Germany). All gels were run in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. Statistical tests included the Mann–Whitney U test, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when more than two groups were compared, and a Newman-Keul’s multiple comparison test for paired values. Differences were considered significant when the P-value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Survival, myocardial function and remodeling

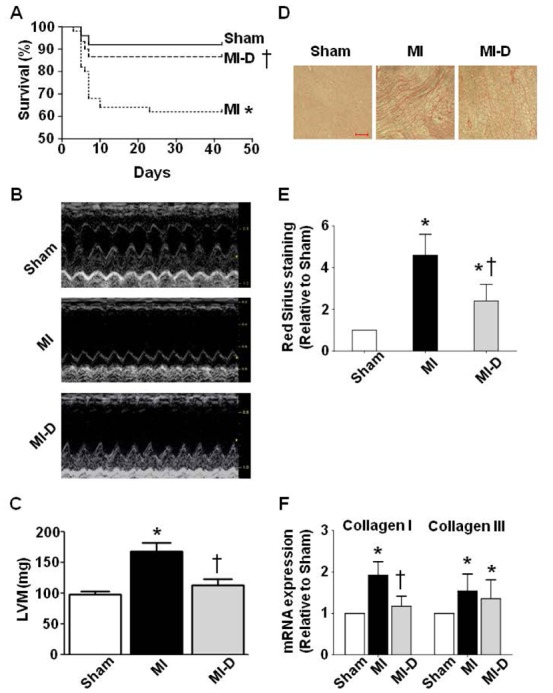

We compared survival in Sham, MI and MI-D mice. Survival declined rapidly in the MI group compared to Sham, while Delapril (MI-D) prevented the high mortality observed in the MI group (Fig. 1A). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the survival of MI-D mice (87%, n=29) was higher than that of MI mice (62%, n= 49; P < 0.05) but not different from the survival of Sham animals (92%, n=24). The body weights (BW, g) of Sham, MI and MI-D mice were indistinguishable (Table 1). However, the heart weight (HW, mg) to BW ratio (HW/BW) was higher in MI than in Sham mice, confirming cardiac hypertrophy, which was reduced by delapril (Table 1). The mean arterial blood pressure was similar in Sham (89.3±2.6 9 mmHg, n=4) and MI (87.9±10.6 9 mmHg, n=4) mice, as reported before (28), and was not modified by delapril in MI-D animals (88.3±2.9 mmHg, n=4), suggesting that the cardiac effects of delapril were independent of blood pressure reduction.

Figure 1. Effects of delapril on survival, cardiac morphology and function.

A. Kaplan-Meier survival curve of MI mice (n=49) compared to Sham (n=24) and MI-D animals (n=29). B. Representative M-mode echocardiographic images of the left ventricular parasternal short axis in awake Sham, MI and MI-D mice. C. Left ventricular mass (LVM) assessed by the Devereux formula from M-mode images. There is a significant increase in LVM in MI mice (n=18) compared to Sham mice (n=18), which is prevented in MI-D mice (n=21). D. Representative images showing levels of fibrosis in Sham, MI and MI-D mice in 10μm-thick heart slices (LV free wall) after Sirius red staining. E. Quantification of Sirius red staining in Sham, MI and MI-D hearts (n=6 in each group). Fibrosis increases 5 fold in MI mice vs. Sham mice. This increase is prevented by delapril. F. Expression of mRNAs for collagen I and III. Expression is increased in MI hearts (n=6) vs. Sham mice (n=6). The increase in collagen I is partially prevented by delapril treatment (MI-D, n=6). *P<0.05 in comparison with Sham mice. †P<0.05 in comparison with MI mice.

Table 1.

Morphological and functional parameters in vivo

| Sham | MI | % Sham | MI-D | % Sham | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | n=9 | n = 9 | n = 18 | ||

| BW (g) | 39.2 ± 2.6 | 38.9 ± 3.0 | 39.7 ± 2.5 | ||

| HW/BW (mg/g) | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.4* | +41 | 6.3 ± 0.3 *† | +17 |

| Echocardiography | n = 18 | n = 18 | n = 21 | ||

| Systole | |||||

| PWT (mm.10−1) | 14.9 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 1.1* | −23 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | −15 |

| LVEsD (mm.10−1) | 19.4 ± 0.6 | 56.4 ± 3.2* | +191 | 44.9 ± 1.4*† | +131 |

| Diastole | |||||

| PWT (mm.10−1) | 7.58 ± 0.27 | 6.33 ± 0.29 * | −16 | 6.34 ± 0.42 * | −16 |

| LVEdD (mm.10−1) | 40.7 ± 1.0 | 65.0 ± 2.7* | +60 | 54.4 ± 1.4*† | +34 |

| SF (%) | 52 ± 1 | 13 ± 2* | −75 | 17 ± 1*† | −67 |

| Haemodynamic | n = 14 | n = 14 | n = 15 | ||

| Pressure | |||||

| LVEsP (mmHg) | 83 ± 3 | 67 ± 3* | −19 | 65 ± 4* | −22 |

| LVEdP (mmHg) | 0 ± 3 | 7 ± 2* | −3 ± 1 † | ||

| Max dP/dt (mmHg/s) | 5223 ± 551 | 4129 ± 198 * | −21 | 4518 ± 380 | −13 |

| Min dP/dt (mmHg/s) | −3934 ± 460 | −3037 ± 157 * | −23 | −3401 ± 226 | −14 |

| EDV (μl) | 23 ± 1 | 29 ± 1* | +21 | 27 ± 1*† | +17 |

| SV (μl) | 17 ± 1 | 26 ± 1* | +53 | 23 ± 1*† | +35 |

BW: body weight; HW: heart weight; PWT: posterior wall thickness; LVEsD: LV end-systolic diameter; LVEdD: LV end-diastolic diameter; SF: shortening fraction; LVEsP: LV end diastolic pressure; LVEsP: LV End systolic pressure; Max dP/dt: maximum rate of increase in pressure during contraction (positive slope); Min dP/dt: Minimum rate of decrease in pressure during relaxation (negative slope); EDV: end-disatolic volume; SV: systolic volume. Values given are means ± S.E.M.;

P<0.05 MI compared to Sham.

P<0.05 MI-D compared to MI.

In terms of cardiac morphology and function, 2D echocardiography in vivo (Fig. 1B) showed that MI mice had an augmented LVM (Fig. 1C) and LV dilation as assessed by the end-diastolic diameter (LVEdD) (Table 1). Posterior wall thickness (PWT) was reduced in MI and MI-D mice as compared to Sham mice (Table 1). Delapril treatment prevented the increase of the LVM (Fig. 1C) and attenuated LV dilation (Table 1). At the functional level, MI hearts exhibited a dramatic reduction of the shortening fraction (SF) (Table 1), reflecting a major alteration of ventricular function. Although MI-D mice exhibited signs of improved systolic function, the benefit was small (Table 1), consistent with the extensive cardiomyocyte necrosis caused by the large infarct of the LV in this model.

We further evaluated cardiac function based on LV pressure-volume relationships in vivo. In MI mice, the LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEdP) and LV end-systolic pressure (LVEsP) were, respectively, higher and lower than in Sham mice (Table 1). Furthermore, the maximal slope of the increment of systolic pressure (dP/dt max), an index of myocardial contractility, was decreased whereas the maximal slope of the increment of diastolic pressure (dP/dt min), an index of relaxation, was increased (Table 1). MI mice also exhibited larger LV cavity volumes (end systolic and diastolic) than Sham animals. Delapril treatment had no effect on LVSP, confirming that the dose of delapril used did not reduce blood pressure (Table 1). However, it attenuated the effect of MI on LV cavity volume with a remarkable benefit in terms of diastolic pressure (Table 1). Picrosirius red staining showed interstitial and scar fibrosis in the hearts of MI mice (vs. Sham) (Fig. 1D,E). The expression of both collagen I and collagen III mRNAs (Fig. 1F) was higher, consistent with the phenotype of HF at the molecular level. Delapril treatment attenuated both fibrosis and collagen I mRNA expression.

Cell contraction and Ca2+ transients

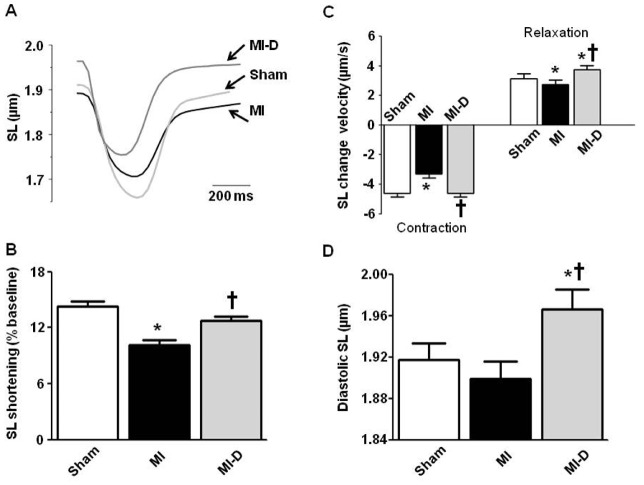

We next investigated the effect of delapril on cardiomyocytes isolated from the non-infarcted area comprised of viable cells subjected to cardiac remodeling following the MI. In unloaded intact single cardiomyocytes from MI mice (vs. Sham), sarcomere length (SL) shortening, reflecting cell contraction during field stimulation, was decreased (Fig. 2A,B). Contraction and relaxation velocities were also reduced (Fig. 2C). Delapril treatment prevented all of these changes. Notably, the diastolic SL was larger in MI-D than in MI or even Sham mice, consistent with the remarkable effect of delapril on cell relaxation (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Effects of delapril on cardiomyocyte sarcomere length.

A. Representative contraction, indexed by sarcomere length (SL) shortening at 1 Hz, of intact myocytes isolated from Sham, MI and MI-D mice. B. Mean ± S.E.M. of the amplitude of SL shortening from Sham, MI and MI-D mice. C. Mean ± S.E.M. of the kinetics of contraction and relaxation from Sham, MI and MI-D mice. D. Mean ± S.E.M. of diastolic SL. Delapril treatment in MI-D cells increases diastolic SL when compared to Sham and MI cells. In B, C and D: Sham (n=26), MI (n=31) and MI-D (n=23). *P<0.05 in comparison with Sham mice. †P<0.05 in comparison with MI mice.

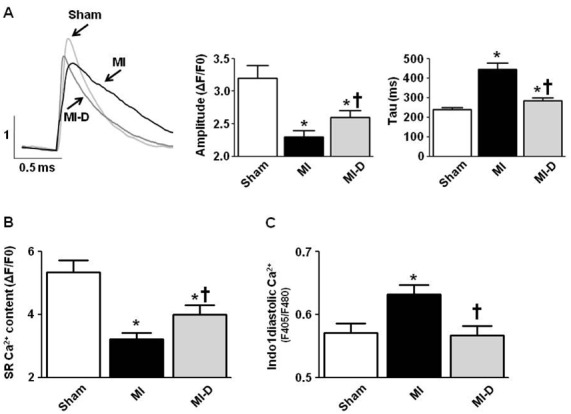

We measured the Ca2+ transients of field-stimulated cardiomyocytes loaded with fluo-4 AM. The amplitude of Ca2+ transients was smaller in MI mice (2.3±0.1, n=25) than in Sham mice (3.2±0.2, n=33; P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). Their time to peak and decay (τ) were delayed in MI mice (Fig. 3A). In parallel, we determined that the Ca2+ content of the SR, assessed by a challenge with caffeine leading to full Ca2+ release, was lower in MI mice than in Sham mice (Fig. 3B), which could account for the decrease in the Ca2+-transient amplitude. All these alterations were partially prevented by treatment with delapril, which had a astonishing effect on Ca2+-transient decay kinetics (Fig. 3A). We further investigated diastolic Ca2+ using the ratiometric indicator indo-1. Diastolic Ca2+ was higher in MI mice than in Sham mice, an increase that was completely prevented by delapril (Fig. 3C). Delapril treatment thus, had a notable effect on cell relaxation, Ca2+-transient decay and diastolic Ca2+.

Figure 3. Effects of delapril on Ca2+ transients in LV myocytes.

A. Top left panel: Representative Ca2+transients from Sham (n=33), MI (n=27) and MI-D cardiomyocytes (n=41) loaded with Fluo-4 AM, observed by confocal microscopy. Top center and right panels: Average Ca2+-transient amplitude and Ca2+ reuptake kinetics (tau). B: SR Ca2+ content in Sham (n=9), MI (n=10) and MI-D cells (n=8) after caffeine application (100 μM). C. Mean ± S.E.M. of diastolic Ca2+ concentrations from Sham (n=23), MI cells (n=27) and MI-D cells (n=18) from the LV loaded with the fluorescent indicator Indo-1 AM. *P<0.05 in comparison with Sham mice. †P<0.05 in comparison with MI mice.

Expression of Ca2+ handling proteins

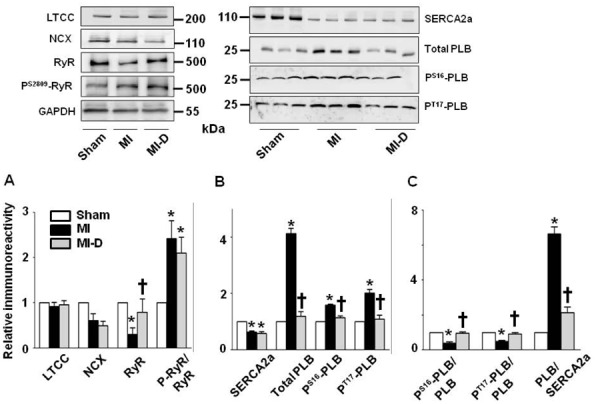

We measured the expression level of Ca2+ handling proteins involved in E-C coupling (Fig. 4). The abundance of the voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) protein, responsible for Ca2+ entry into cardiomyocytes, and of the NCX protein was similar in Sham, MI and MI-D mice. The abundance of the ryanodine receptor (RyR), responsible for Ca2+ release from the SR, following Ca2+ entry via LTCCs, was decreased in MI (vs. Sham) mice, a change that was prevented by delapril (Fig. 4A). In contrast, its phosphorylated form (P-RyR) was increased, and this increase was resistant to delapril treatment (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Effect of delapril on excitation-contraction coupling proteins.

Top: Representative Western blot for LTCC: L-type Ca2+ channel; NCX: Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; RyR: ryanodine receptor 2; P-RyR: phosphorylated ryanodine receptor; SERCA2a: SR Ca2+ ATPase 2a; Total PLB: total phospholamban; PS16-PLB: PLB phosphorylated by PKA at Serine 16; PT17-PLB: phospholamban phosphorylated by CaMKII at the threonine-17 site. A. Mean ± S.E.M. of LTCC, NCX, RyR and P-RyR/RyR protein expression levels in Sham (n=5), MI (n=6), and MI-D mice (n=6). B. Mean ± S.E.M. of SERCA2a, Total PLB, PS16-PLB and PT17-PLB protein expression levels. C. Mean ± S.E.M. of PS16-PLB/PLB, PT17-PLB/PLB and PLB/SERCA2a ratio. Molecular Weight in kDa. *P<0.05 in comparison with Sham mice. †P<0.05 in comparison with MI mice.

The slowing of Ca2+-transient decay, as seen in MI cells (Fig. 3), usually reflects impaired Ca2+ reuptake due to the weakened activity of the SR Ca2+ ATPase 2 (SERCA2a). Immunoblot analysis showed that SERCA2a expression was decreased in MI (vs. Sham) mice (Fig. 4B). Since SERCA2a activity is regulated by the inhibitory protein phospholamban (PLB) [29, 30], we also investigated the effect of MI on this protein. Both protein expression and phosphorylation of phospholamban (P-PLB) at the serine 16 and threonine 17 residues (Ser16-PLB and Thr17-PLB), were increased in MI hearts (Fig. 4B). Delapril treatment had no effect on the reduction of SERCA2a abundance but remarkably, prevented the increase of PLB protein and phosphorylation levels. Importantly, both the decrease in the P-PLB/PLB ratio (for both Ser16-PLB and Thr17-PLB) and the increase in the PLB/SERCA2a ratio induced by MI were abolished by delapril (Fig. 4C).

Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments

Cardiomyocyte force development depends on both the amount of Ca2+ released by the SR and the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile machinery. To determine the effect of delapril on LV myofilament function, we measured the relationship between intracellular Ca2+ concentration and maximal isometric tension normalized to the cross-sectional area in single permeabilized LV myocytes, as described previously [31]. Cross-sectional area was greater in the MI group (248±16 μm2, n=20) than in Sham mice (203±18 μm2, n=16), consistent with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. This effect was prevented by delapril (198±14 μm2, n=22, P<0.05). In permeabilized cardiomyocytes, the resting SL was unchanged in MI (1.88±0.01 μm) and MID (1.89±0.01 μm) mice when compared to the Sham group (1.90±0.01 μm). In contrast, in MI mice (when compared with Sham animals), the maximum Ca2+-saturated force (Fmax) was decreased, and the curve representing the tension–pCa relationship was shifted to the right due to a reduction in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (pCa50: 5.66±0.01, n=20 in MI, vs. pCa50: 5.72±0.02, n=16 in Sham mice, P<0.05; Fig. 5A,B). Delapril treatment had a powerful preventive effect on changes in both maximal active tension and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (pCa50: 5.74±0.02, n=22; P<0.05 for MI-D vs. MI).

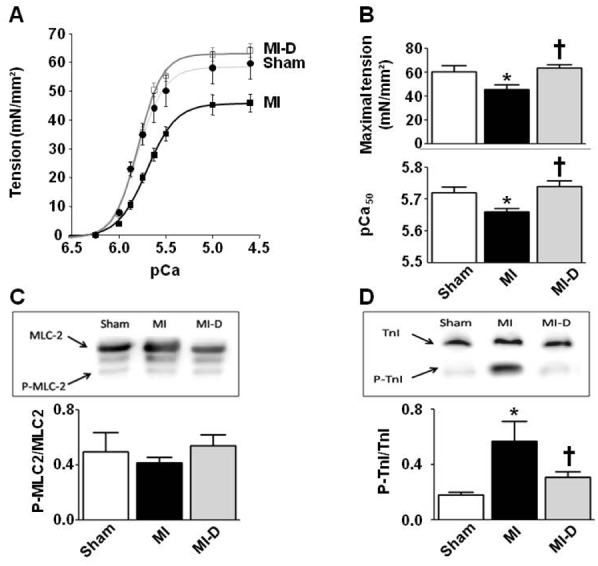

Figure 5. Effects of delapril on contractile machinery in permeabilized cardiomyocytes.

A. Relationship between Ca2+-activated tension and intracellular Ca2+ content measured at an SL of 1.9 μm in permeabilized cardiomyocytes from Sham (n=16), MI (n=20) and MI-D mice (n=22). The relationship was fitted to a modified Hill equation and the pCa at which half the maximal tension is developed (pCa50) was determined as an index of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (see Methods for more details). B. Mean ± S.E.M. of maximal tension (top) and pCa50 (bottom) obtained from permeabilized Sham, MI and MI-D cells C. Effect of delapril on the phosphorylation level of MLC-2 in permeabilized cardiac strips from Sham (n=5), MI (n=11) and MI-D hearts (n=11). Phosphorylation levels were determined by Western blotting using a P-MLC2 antibody as described in methods. D. Effect of delapril on the phosphorylation level of TnI in permeabilized cardiac strips from Sham (n=7), MI (n=8) and MI-D hearts (n=8). Results are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. *P<0.05 in comparison with Sham mice. †P<0.05 in comparison with MI mice.

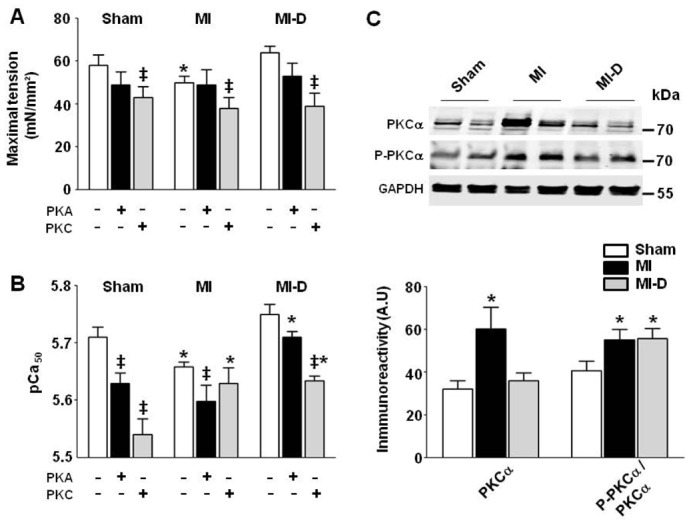

The Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments is regulated by the phosphorylation status of sarcomeric proteins such as MLC2 and TnI [32]. The phosphorylation level of MLC2 was unchanged in the ventricles of MI mice when compared with Sham mice, as well as after delapril treatment (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the phosphorylation level of TnI at the protein kinase A (PKA) sites Ser23/24, known to result in decreased Ca2+ sensitivity, was increased in MI hearts, an effect prevented by delapril (Fig. 5D) suggesting post-translational modifications of regulatory contractile proteins mediated by kinases. We next evaluated the contribution of kinases such as PKA and protein kinase C (PKC) to modulation of Ca2+ sensitivity in MI and MI-D mice by incubating myofilaments with the two activated kinases. PKA had no effect on maximal tension in the three groups (Fig. 6A). PKA decreased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in both Sham and MI mice by 0.09 and 0.06 pCa unit, respectively (Fig. 6B). In contrast, PKA had no significant effect in MI-D mice (decrease of 0.04 pCa unit). Overstimulation with PKA normalized myofilaments Ca2+ sensitivity in Sham and MI myocytes but not in MI-D cells, where it remained higher than in Sham and MI, suggesting that delapril protects myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity by a pathway independent of PKA signaling. Next, we explored the PKC signaling pathway known to be involved in angiotensin II effects through AT1R binding [24], and to regulate the myofilament function during HF [33]. Incubation of the myofilaments with activated PKC decreased the maximal tension in the three groups to a similar level (Fig. 6A). PKC also decreased the pCa50 in Sham and MI-D mice by 0.18 and 0.12 pCa unit, respectively, but had no effect in MI mice with a non-significant decrease of pCa50 of 0.03 pCa unit (Fig. 6B). Altogether the results indicate that myofilament function is affected by both PKA and PKC pathways in MI mice while PKC signaling is downregulated in MI-D mice. We thus determined the expression level of PKC-α and its activation evaluated by the level of phosphorylation at Ser657 (Fig. 6C). The expression and activation of PKC-α increased in MI mice. Delapril treatment prevented the increase in PKC-α expression and did not affect the level of activation compared with MI animals (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Effects of delapril on contractile machinery in permeabilized cardiomyocytes: involvement of the PKA and PKC pathways.

A. Maximal tension developed by isolated Sham (n=12), MI (n=9) and MI-D (n=9) cardiomyocytes, under control conditions and after PKA or PKC incubation. B. The pCa50 developed by isolated cardiomyocytes under control conditions and after PKA or PKC incubation. C. Top panel: representative Western blot for PKCα, P-PKCα and GAPDH; Molecular Weight in kDa. Bottom panel: PKCα expression levels, relative to GAPDH content, and P-PKCα/PKCα ratio. Results are expressed as means ± S.E.M (n=5 mice). *P<0.05 in comparison with Sham mice with the same treatment (panel C). ‡ P<0.05 in comparison with non-treated cells within each group.

DISCUSSION

ACE-I have been studied extensively over the last three decades and their clinical benefits are well-established. However, their molecular effects are complex and unclear. In particular, all cardiac therapeutical benefits are not supported exclusively by blood pressure reduction. Our study provides novel information about delapril effects at the cardiomyocytes level. We showed the strong benefits of delapril treatment on the contraction and relaxation of viable cardiomyocytes after MI in a model of cardiac remodeling in mice, which occurred independently of blood pressure reduction. Chronic treatment, started 24 hours after infarction, prevented the intracellular Ca2+ overload that occurs following MI and preserved the relaxation of cardiomyocytes. We also show for the first time that, in addition, delapril maintained the Ca2+ sensitivity of contractile myofilaments at normal levels. Both effects resulted in a remarkable preservation of cellular contraction and attenuated the typical transition toward HF after MI. Ours results were also consistent with the modulation of PKC expression.

Our experimental mice model reproduced critical features of post-ischemic HF, including depressed myocardial contraction and relaxation, chamber dilation, increased LV mass, and akinesia of the anterior wall due to a large infarcted area. Structural remodeling and functional alterations of the non necrosed tissue were accompanied by fibrosis and the increased expression of mRNAs for HF markers (Collagen I and III). At the cardiomyocyte level, contraction was depressed due to reduced SR Ca2+ load and systolic Ca2+ release, relaxation was slowed owing to blunted Ca2+ reuptake that resulted in a diastolic Ca2+ overload, and the Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments was reduced [12, 34, 35]. At the protein level, HF remodeling was associated with changes in the abundance and/or phosphorylation levels of Ca2+-handling proteins, including SERCA2a, PLB and RyR2, consistent with earlier reports [12, 34, 35].

ACE-I are among the most beneficial drugs used in HF patients. ACE-I therapy improves survival after MI, and large clinical trials point to the importance of initiating therapy as early as possible [3, 36]. In our MI mouse model, chronic treatment with a non-hypotensive dose of delapril (6 mg/kg) reproduced the expected cardiac effects of ACE-I, including attenuated LV chamber dilation, increased LVM, reduced myocardial fibrosis and collagen production [37]. Similar beneficial effect has been described with perindopril, which prevents cardiac hypertrophy without affecting systemic blood pressure in the rat with HF after MI [38]. The anti-fibrotic effects of delapril were also comparable to those of a non-hypotensive dose of fosinopril (1 mg/kg; compared to a 25 mg/kg antihypertensive dose), which has also been shown to restore the β-adrenergic signal transduction pathway independently of the regression of hypertrophy [39]. Our data are consistent with ACE inhibition delaying the transition from hypertrophy to HF by targeting mechanisms intrinsic to cardiomyocytes, in addition to its anti-fibrotic effects [40].

A major finding of our study, focused on the post-MI remodeling of cardiomyocytes, was that delapril preserved the normal contraction/relaxation cycle and attenuated SR dysfunction in the surviving cells. Delapril stabilized the amplitude and the onset of contraction through the normalization of Ca2+-transient amplitude and kinetics, in line with reports showing improved cell shortening, Ca2+-transient amplitude and SERCA2a activity in aortic-banded rats and guinea-pigs treated with the ACE-I ramipril [40, 41]. In our model, delapril did not affect the level of expression of SERCA2a and NCX. We propose that delapril promotes efficient reuptake of Ca2+ into the SR by maintaining SERCA2a activity through normal P-PLB/PLB (for both PS16-PLB and PT17-PLB) and PLB/SERCA2a ratios [29, 30, 42]. In addition, delapril attenuated the reduction in RyR2 abundance in viable cardiomyocytes (see also [43]), thereby favoring Ca2+ release in systole. Surprisingly, the higher PKA-phosphorylation level of RyR2, which has previously been associated with Ca2+ leakage from the SR in HF [44], was not prevented by delapril. Therefore, if we were to assume that RyR2 was still leaky in the presence of delapril, which might explain the lower SR Ca2+ content, the beneficial effect of delapril on SERCA2a activity was enough to maintain the normal decay of the Ca2+ transient (and relaxation) and normal diastolic cytoplasmic Ca2+. Several group proposed an increase of NCX expression as an important mechanism to rescue the compromised SERCA2a function in HF in both human [45–47] and experimental models [48, 49]. Surprisingly, we noted no change in the NCX expression in MI and MI-D mice, which may be in line with evidence for different phenotypes in HF (hearts with increased NCX and unchanged SERCA2a; and hearts with decreased SERCA2a and unchanged levels of NCX) [45] although other groups reported a decrease of NCX during HF [50–52].

Another key finding of our study was that delapril treatment preserved the maximum Ca2+-saturated active force and Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments in surviving cardiomyocytes after MI. In MI mice, the altered Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments involves the increased activity of both PKA and PKC (Fig. 6B), leading notably to the phosphorylation of cTnI, as previously shown in other rodents [33, 53]. In the present study, the abnormal function of the troponin complex, related to the augmented phosphorylation of cTnI in MI, was prevented by delapril. Interestingly, delapril limited the impact of exogenous PKA in decreasing the pCa50 in MI-D mice, which may indicate that delapril does not prevent PKA activation but rather affects protein phosphorylation of TnI by another pathway. The large decrease of pCa50 by exogenous activated PKC in MI-D mice suggests a downregulation of PKC signaling. This is consistent with the decrease in PKC expression reported in the present study and with other works showing that imidapril and/or ramipril can block early cardiac remodeling via angiotensin receptor (AT1)-dependent mechanisms [54–56]. It has been recently proposed that during HF downregulation of β-receptor signaling and PKA phosphorylation of cTnI exposes sites for phosphorylation to an already hyperactive PKC-α, which then hyperphosphorylates cardiac troponin I at Ser 23, 24 and thus promotes myofilament decompensation [57]. Previous studies in reconstituted filaments showed that PKC isozymes can cross phosphorylate cTnI at Ser 23, 24 sites [58, 59]. Therefore, delapril may change phosphorylation level of TnI by decreasing PKC signaling pathway. These mechanisms warrant further investigation.

In conclusion, the beneficial effect of ACE-I therapy with delapril on adverse cardiac remodeling occurs by limiting both the fibrosis, with consequences on myocardial wall stiffness, and the loss of contraction of viable cardiomyocytes. Normal contractility and relaxation were preserved due to the prevention of diastolic Ca2+ overload and the loss of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. The mechanisms underlying these effects seem to be related to the maintenance of SERCA2a activity and the reduction of PKCα expression, respectively, in cardiomyocytes. Our data support a major role for ACE-I in the regulation of the functions of SERCA2a and PKC in the post-ischemic failing heart. Associated with a reduction in fibrosis, this may explain the survival benefits of ACEI therapy in clinical studies, through the improvement of cardiac function, by maintaining excitation-contraction coupling of viable cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roberta Razzetti for careful reading and comments on this manuscript, and Pr. Ole Sejersted and Halvor Kjean Mork for helpful discussions during this study. This work was supported in part by ANR (GENOPAT N°RPV08141FSA).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ACE-I

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- Max dP/dt

maximum rate of increase in pressure during contraction (positive slope)

- Min dP/dt

minimum rate of decrease in pressure during relaxation (negative slope)

- E-C

excitation contraction

- Fmax

maximum Ca2+-saturated force

- HF

heart failure

- LTCC

L-type calcium channel

- LV

left ventricle

- LVEdP

left ventricle end-diastolic pressure

- LVEsP

left ventricle end-systolic pressure

- LVM

left ventricular mass

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MI-D

myocardial infarction mice treated with delapril

- MLC2

myosin light chain 2

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLB

phospholamban

- P-PLB

phosphorylated phospholamban

- P-RyR

phosphorylated ryanodine receptor

- PV

pressure volume

- SERCA2a

SR Ca2+ ATPase 2

- SL

sarcomere lenght

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- RAS

renin angiotensin system

- RYR

ryanodine receptor

References

- 1.Unger T. The role of the renin-angiotensin system in the development of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(2A):3A–9A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02321-9. discussion 10A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sleight P. Angiotensin II and trials of cardiovascular outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(2A):11A–6A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02322-0. discussion 6A–7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flather MD, Yusuf S, Kober L, et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;355(9215):1575–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbull F, Neal B, Pfeffer M, et al. Blood pressure-dependent and independent effects of agents that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2007;25(5):951–8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280bad9b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litwin SE, Katz SE, Weinberg EO, et al. Serial echocardiographic-Doppler assessment of left ventricular geometry and function in rats with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition attenuates the transition to heart failure. Circulation. 1995;91(10):2642–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.10.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks WW, Bing OH, Robinson KG, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on myocardial fibrosis and function in hypertrophied and failing myocardium from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circulation. 1997;96(11):4002–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakata Y, Yamamoto K, Mano T, et al. Temocapril prevents transition to diastolic heart failure in rats even if initiated after appearance of LV hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57(3):757–65. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AIRE. Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Lancet. 1993;342(8875):821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, et al. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;333(25):1670–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wehrens XH, Marks AR. Novel therapeutic approaches for heart failure by normalizing calcium cycling. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(7):565–73. doi: 10.1038/nrd1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye DM, Hoshijima M, Chien KR. Reversing advanced heart failure by targeting Ca2+ cycling. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:13–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.052407.103237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bers DM. Altered cardiac myocyte Ca regulation in heart failure. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:380–7. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00019.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jugdutt BI. Preventing adverse remodeling and rupture during healing after myocardial infarction in mice and humans. Circulation. 2010;122(2):103–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.969410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren B, Shao Q, Ganguly PK, et al. Influence of long-term treatment of imidapril on mortality, cardiac function, and gene expression in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;82(12):1118–27. doi: 10.1139/y04-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo X, Chapman D, Dhalla NS. Partial prevention of changes in SR gene expression in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction by enalapril or losartan. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;254(1–2):163–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1027321130997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao Q, Ren B, Zarain-Herzberg A, et al. Captopril treatment improves the sarcoplasmic reticular Ca(2+) transport in heart failure due to myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31(9):1663–72. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coca A. Manidipine plus delapril in patients with Type 2 diabetes and hypertension: reducing cardiovascular risk and end-organ damage. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2007;5(2):147–59. doi: 10.1586/14779072.5.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bevilacqua M, Vago T, Rogolino A, et al. Affinity of angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for N- and C-binding sites of human ACE is different in heart, lung, arteries, and veins. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28(4):494–9. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acharya KR, Sturrock ED, Riordan JF, Ehlers MR. Ace revisited: a new target for structure-based drug design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(11):891–902. doi: 10.1038/nrd1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Razzetti R, Acerbi D. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacologic properties of delapril, a lipophilic nonsulfhydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(18):7F–12F. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarnavski O, McMullen JR, Schinke M, et al. Mouse cardiac surgery: comprehensive techniques for the generation of mouse models of human diseases and their application for genomic studies. Physiol Genomics. 2004;16(3):349–60. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masson S, Masseroli M, Fiordaliso F, et al. Effects of a DA2/alpha2 agonist and a beta1-blocker in combination with an ACE inhibitor on adrenergic activity and left ventricular remodeling in an experimental model of left ventricular dysfunction after coronary artery occlusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34(3):321–6. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finsen AV, Christensen G, Sjaastad I. Echocardiographic parameters discriminating myocardial infarction with pulmonary congestion from myocardial infarction without congestion in the mouse. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(2):680–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00924.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joho S, Ishizaka S, Sievers R, et al. Left ventricular pressure-volume relationship in conscious mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(1):H369–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00704.2006. Epub 2006/08/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thireau J, Aimond F, Poisson D, et al. New insights into sexual dimorphism during progression of heart failure and rhythm disorders. Endocrinology. 2010;151(4):1837–45. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fauconnier J, Thireau J, Reiken S, et al. Leaky RyR2 trigger ventricular arrhythmias in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(4):1559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908540107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flagg TP, Cazorla O, Remedi MS, et al. Ca2+-independent alterations in diastolic sarcomere length and relaxation kinetics in a mouse model of lipotoxic diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2009;104(1):95–103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quang KL, Naud P, Qi XY, et al. Role of T-type calcium channel subunits in post-myocardial infarction remodelling probed with genetically engineered mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91(3):420–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minamisawa S, Hoshijima M, Chu G, et al. Chronic phospholamban-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase interaction is the critical calcium cycling defect in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell. 1999;99(3):313–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt JP, Kamisago M, Asahi M, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure caused by a mutation in phospholamban. Science. 2003;299(5611):1410–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1081578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cazorla O, Lucas A, Poirier F, et al. The cAMP binding protein Epac regulates cardiac myofilament function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(33):14144–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812536106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamdani N, Kooij V, van Dijk S, et al. Sarcomeric dysfunction in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77(4):649–58. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Allen EJ, et al. Augmented protein kinase C-alpha-induced myofilament protein phosphorylation contributes to myofilament dysfunction in experimental congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 2007;101(2):195–204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hobai IA, O’Rourke B. Decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content is responsible for defective excitation-contraction coupling in canine heart failure. Circulation. 2001;103(11):1577–84. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piacentino V, 3rd, Weber CR, Chen X, et al. Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;92(6):651–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000062469.83985.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latini R, Maggioni AP, Flather M, et al. ACE inhibitor use in patients with myocardial infarction. Summary of evidence from clinical trials. Circulation. 1995;92(10):3132–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartha E, Kiss GN, Kalman E, et al. Effect of L-2286, a poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase inhibitor and enalapril on myocardial remodeling and heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52(3):253–61. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181855cef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiba K, Moriyama S, Ishigai Y, et al. Lack of correlation of hypotensive effects with prevention of cardiac hypertrophy by perindopril after ligation of rat coronary artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;112(3):837–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohm M, Castellano M, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Dose-dependent dissociation of ACE-inhibitor effects on blood pressure, cardiac hypertrophy, and beta-adrenergic signal transduction. Circulation. 1995;92(10):3006–13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeishi Y, Bhagwat A, Ball NA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on protein kinase C and SR proteins in heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(1 Pt 2):H53–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boateng SY, Naqvi RU, Koban MU, et al. Low-dose ramipril treatment improves relaxation and calcium cycling after established cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280(3):H1029–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kadambi VJ, Ponniah S, Harrer JM, et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of phospholamban alters calcium kinetics and resultant cardiomyocyte mechanics in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(2):533–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI118446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi F, Sanbe A, Takeo S. Effects of long-term treatment with trandolapril on sarcoplasmic reticulum function of cardiac muscle in rats with chronic heart failure following myocardial infarction. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123(2):326–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reiken S, Lacampagne A, Zhou H, et al. PKA phosphorylation activates the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) in skeletal muscle: defective regulation in heart failure. J Cell Biol. 2003;160(6):919–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasenfuss G, Schillinger W, Lehnart SE, et al. Relationship between Na+-Ca2+-exchanger protein levels and diastolic function of failing human myocardium. Circulation. 1999;99(5):641–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Studer R, Reinecke H, Bilger J, et al. Gene expression of the cardiac Na(+)-Ca2+ exchanger in end-stage human heart failure. Circ Res. 1994;75(3):443–53. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flesch M, Schwinger RH, Schiffer F, et al. Evidence for functional relevance of an enhanced expression of the Na(+)-Ca2+ exchanger in failing human myocardium. Circulation. 1996;94(5):992–1002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomez AM, Schwaller B, Porzig H, et al. Increased exchange current but normal Ca2+ transport via Na+-Ca2+ exchange during cardiac hypertrophy after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2002;91(4):323–30. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000031384.55006.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wasserstrom JA, Holt E, Sjaastad I, et al. Altered E-C coupling in rat ventricular myocytes from failing hearts 6 wk after MI. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(2):H798–807. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon IM, Hata T, Dhalla NS. Sarcolemmal Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase activity in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1992;262(3 Pt 1):C664–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.3.C664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Makino N, Hata T, Sugano M, et al. Regression of hypertrophy after myocardial infarction is produced by the chronic blockade of angiotensin type 1 receptor in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28(3):507–17. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sethi R, Dhalla KS, Ganguly PK, et al. Beneficial effects of propionyl L-carnitine on sarcolemmal changes in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42(3):607–15. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Kobayashi T, et al. Left ventricular myofilament dysfunction in rat experimental hypertrophy and congestive heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(5):H2344–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00541.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Liu X, Sentex E, et al. Increased expression of protein kinase C isoforms in heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284(6):H2277–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00142.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simonis G, Dahlem MH, Hohlfeld T, et al. A novel activation process of protein kinase C in the remote, non-ischemic area of an infarcted heart is mediated by angiotensin-AT1 receptors. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(11):1349–58. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simonis G, Braun MU, Kirrstetter M, et al. Mechanisms of myocardial remodeling: ramiprilat blocks the expressional upregulation of protein kinase C-epsilon in the surviving myocardium early after infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41(5):780–7. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200305000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Sievert GA, et al. Interventricular differences in myofilament function in experimental congestive heart failure. Pflugers Arch. 2011;462(6):795–809. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jideama NM, Noland TA, Jr, Raynor RL, et al. Phosphorylation specificities of protein kinase C isozymes for bovine cardiac troponin I and troponin T and sites within these proteins and regulation of myofilament properties. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(38):23277–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noland TA, Jr, Raynor RL, Kuo JF. Identification of sites phosphorylated in bovine cardiac troponin I and troponin T by protein kinase C and comparative substrate activity of synthetic peptides containing the phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(34):20778–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]