Abstract

Older drivers are primarily overinvolved in crashes at intersections, and failure to attend to regions that contain relevant information about potential hazards is a major contributor to this problem. Corroborating this, we have found that older drivers in both controlled scenarios on a driving simulator and somewhat less controlled situations on the road attend to (i.e., fixate) target regions in intersections significantly less frequently than do younger experienced drivers. Moreover, we have developed a training program that substantially improves older drivers’ attention to these regions. Together, these findings indicate that older drivers’ less frequent scanning of regions at intersections from which hazards may emerge may be due to their developing something like an unsafe habit rather than to deteriorating physical or mental capabilities and thus that training may be effective in reducing crashes.

Keywords: safe driving, older drivers, eye movements

Introduction

Older drivers, especially those over 70 years old, are overinvolved in right-of-way crashes, primarily in intersections, where hazards typically emerge from the side of the driver’s vehicle (Clarke, Ward, Bartle, & Truman, 2010). This is in spite of the fact that older drivers appear to be aware of the problem and make efforts to remediate it (Eck & Winn, 2002). The overinvolvement of older drivers in such crashes has been traced to diminished cognitive abilities such as a narrowing of drivers’ useful field of view (Ball & Owsley, 1991), a loss of the ability to selectively attend to what is important (Hakamies-Blomqvist, Sirén, & Davidse, 2004), poor judgment of vehicle speed (Spek, Wieringa, & Janssen, 2006), and diminished physical abilities that interfere with their ability to control the vehicle (Yan, Radwan, & Guo, 2007) and failure to turn their heads (Isler, Parsonson, & Hansson, 1997).

There is also evidence that older drivers scan at intersections less effectively than do younger experienced drivers (Bao & Boyle, 2009; Braitman, Kirley, Ferguson, & Chaudhary, 2007; Clarke et al., 2010). This could be due to one or more of the causes above (e.g., older drivers could be failing to scan less effectively because they are attending to unimportant information). An attempt to determine whether scanning itself, in the absence of distractions and other traffic, was a problem was recently studied on a driving simulator and in the field. The results clearly indicated that a failure to scan for potential hazards was by itself a possible cause of crashes (Romoser & Fisher, 2009; Romoser, Fisher, Mourant, Wachtel, & Sizov, 2005). Moreover, the older drivers’ failure to scan can be remediated by a brief training program (Romoser & Fisher, 2009). This fact, together with our detailed analysis of the comparison of scanning behavior of older experienced drivers with that of younger experienced drivers, has led us to the surprising conclusion that much of older drivers’ problems with scanning in intersections is attributable not solely to cognitive or physical decline but also to the gradual development over time of something akin to an “unsafe habit.”

Our research addresses three central questions about older drivers’ failure to scan appropriately at intersections: (a) whether this is just a general tendency to look around less while driving or whether it occurs mainly at certain critical periods (e.g., when approaching and entering an intersection); (b) whether older drivers’ failure to monitor for potential hazards is due solely to the various changes in mental abilities described above, such as an increase in distractibility or decrease in the useful field of view; and (c) whether older drivers’ failure to scan at intersections is mainly due to musculoskeletal problems.

To help answer these questions, we will first discuss some data comparing the scanning behavior of older drivers (over 70) and younger experienced drivers (aged 25–55). We have studied the differences between these groups on the road (Romoser & Fisher, 2009) and in a driving simulator (Romoser et al., 2005; Romoser & Fisher, 2009) and have found similar differences in both environments. However, since the driving simulator allows more control over the situation, we will limit our analyses below to the simulator data. We will then discuss the training program that remediates these differences and why these results lead to the “unsafe habit” conclusion.

Differences in Scanning Behavior

A typical drive in the simulator contains stretches in which little of interest happens, but there are specific stretches in the drive called scenarios that are of particular interest and are scored (Romoser & Fisher, 2009). The three scenarios we discuss below are all at intersections, and in each of them, there is a potential hazard that the driver needs to monitor (see Fig. 1). They represent the three possible turning behaviors a driver would have to execute at an intersection (a left turn, a right turn, and no turn). Most importantly, each contains a well-defined region that should be monitored when approaching and entering the intersection. That is, in each of the scenarios, a vehicle traveling on another road entering the intersection could have been hidden by either a hill or a bend in the road, and if such a hidden vehicle was going the speed limit, it would be in the intersection three seconds after it first became visible. In each of these scenarios, this vehicle would have the right of way; thus there would be no reason for it to slow down except for trying to avoid a crash. We should emphasize that this potentially crashing vehicle never appeared in any of the scenarios “at the last minute” (i.e., when the driver arrived at the intersection and began the turn), so as not to make drivers hypervigilant by creating crash or near-crash situations.

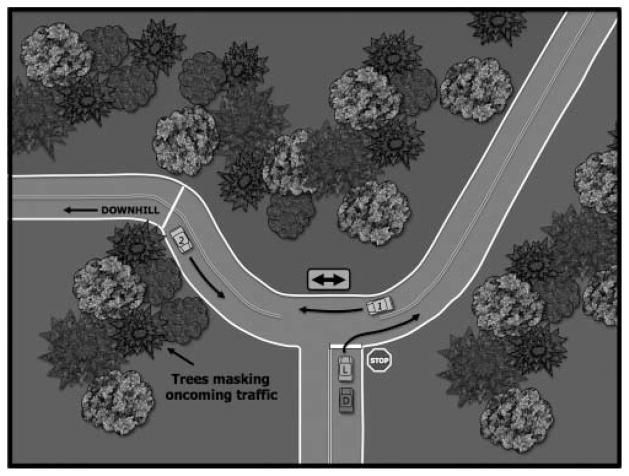

Fig. 1.

Left turn across traffic scenario. The driver (D) turns left at a four-way intersection on to the side street following a lead vehicle (L). Side streets have stop signs, the driver does not.

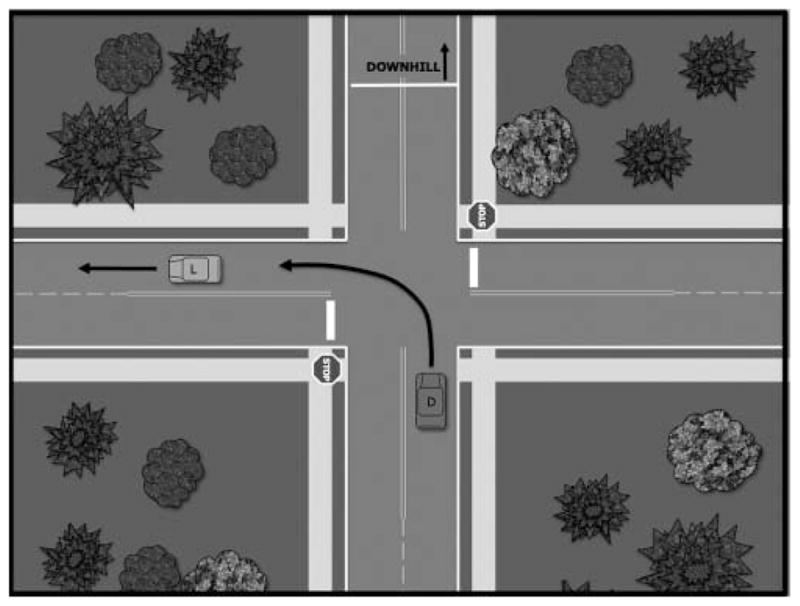

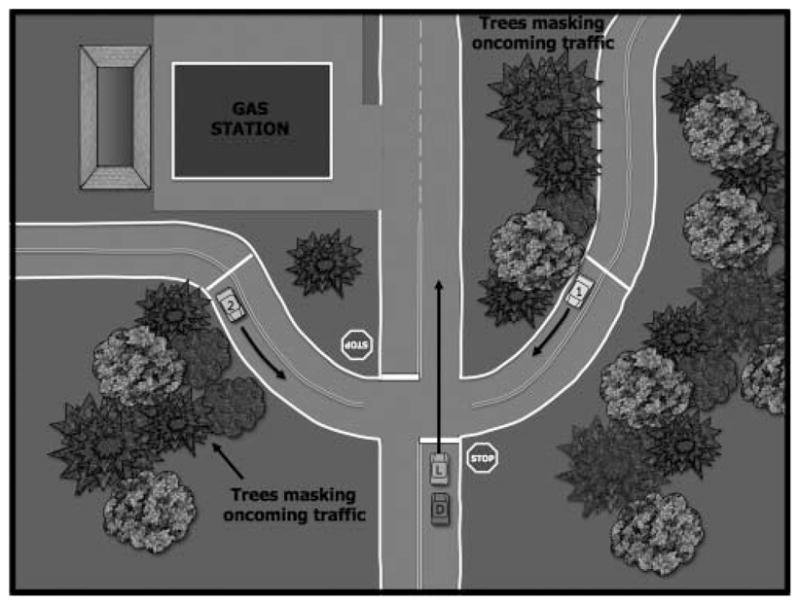

In the first scenario (Fig. 1), the driver and traffic in the opposing lane across the four-way intersection have the right of way. The driver is instructed to make a left turn at the intersection. Thus, the only plausible threat is a car in the opposing lane coming directly toward the driver. In the second (Fig. 2), the driver is instructed to make a right turn at the stem of a T-intersection onto a road where the traffic has the right of way, and this fact is made clear to the driver. Thus, the only plausible threat is a car coming from the left of the driver. In the third (Fig. 3), the driver is instructed to go straight through the intersection. However, the driver has a stop sign and cross traffic has the right of way. As there are restricted sight lines for traffic coming from the right and left, both of these areas need to be checked within three seconds of entering the intersection to be sure that a vehicle is not approaching from one or both sides.

Fig. 2.

Right turn at T-intersection. The driver (D) turns right at a T-intersection following a lead vehicle (L). Prior to the turn, two cross-traffic vehicles (1 and 2) proceed through the intersection to reinforce the concept that cross traffic does not stop.

Fig. 3.

Straight through intersection. The driver (D) proceeds straight through the four-way-stop intersection following the lead vehicle (L). Well prior to entering intersection, vehicles 1 and 2 proceed through the intersection to make clear to the driver that cross traffic does not stop.

In each of these scenarios, we defined a potential threat region that should be monitored just before and immediately after entering the intersection in order to make sure that additional cross-traffic has not materialized. Moreover, there is no moving vehicle or pedestrian that is obviously competing for the driver’s attention. Our analyses show that the only region competing for the driver’s attention is defined by the forward path of the vehicle (i.e., the arrows in the figures attached to the lead, L, vehicle). In the first scenario, this region is somewhat to the left when entering the turn and then straight ahead as the turn is completed. In the second scenario, it is to the right when beginning the turn and then straight ahead as the turn is completed. In the third scenario, with no turn, this region is straight ahead.

Of major interest in the data from the Romoser and Fisher (2009) experiment was the amount of time the driver spent glancing at (i.e., monitoring) the critical potential threat region in the interval when the driver approached and entered the intersection. The critical interval was chosen to be between 2 seconds before the driver’s vehicle entered the intersection and 1 second after the vehicle entered it (when the driver still had some chance of averting a potential crash). Indeed, older drivers monitored the potential threat region significantly less than did younger drivers in this interval for each of the three scenarios, and as we indicated above, the difference between the groups during this interval could be largely accounted for by the fact that the older drivers glanced for a significantly greater amount of time at the forward direction of their car than did the 25- to 55-year-old drivers. (These observed differences extended to a wider range of scenarios, but we are focusing on these three scenarios because they illustrate several important points.)

First, the difference between the older and younger experienced drivers was not merely due to the fact that younger drivers generally look around more. After having negotiated the intersection, there was no difference between the groups in their pattern of scanning behaviors ahead and to the sides. In the first two scenarios, there was also virtually no difference between the groups prior to the critical interval; but in the third, the younger drivers looked around more, probably because more scanning is necessary, as one needs to check for traffic coming both from the left and right. Second, it is unlikely that the difference between groups was due to declining attentional capacities, because there were no distractions present in the intersections or in a surrounding field of view that would compete for processing. Third, the difference in scanning behavior was not plausibly due to declining physical abilities, because the correct scanning behavior in the first scenario was continuing to monitor the road directly in front and no large head movements were required to do this.

The training studies of Romoser and colleagues provide additional evidence that these three classes of explanations are unlikely explanations for the scanning deficits we discussed earlier. Moreover, they suggest what the older drivers’ problem might actually be.

The Effects of Training

These training studies have a classic design that is similar to that used in medical research (Romoser, 2008; Romoser et al., 2005; Romoser & Fisher, 2009). Participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more groups that receive various treatments, and then the performance of the groups is compared after the treatments. In the latest training study, older drivers were filmed as they drove from their homes using their own vehicles to points of their own choosing wearing head-mounted cameras. Three cameras were mounted on each vehicle to give additional views. The control group was given no training or video feedback. Of greater interest were the two different training groups. In the passive training group, the participants were given 30 to 40 minutes of instruction, which included coaching about where to look at intersections and why less careful scanning (e.g., scanning areas from which potential hazards might emerge) was an important cause of many crashes for older drivers. No video feedback of their field drives was provided. In the post-test, this group did no better than the control group. Thus, merely being told to be careful had no effect on behavior.

The training group of interest saw a video replay of their behavior at intersections in the field drive. (Most of the older drivers recognized their failures without prompting.) They also were evaluated in a driving simulator, shown feedback of their behavior at the virtual intersections, and then allowed to practice appropriate scanning behaviors on the simulator. They were then given the same 30 to 40 minutes of instruction that the passive group was given. Notably, there was no training of motor skills. At the end of this training, the older experienced drivers’ performance had increased dramatically and was indistinguishable from the performance of younger experienced drivers. This training was effective both as assessed in a driving simulator and on the road. Moreover, the effects of training have endured both in a 3-month follow-up (Romoser & Fisher, 2009) and in a 12-month follow-up (Romoser, 2011).

It thus seems quite unlikely that mental or physical “hardware” problems could be the cause of the scanning deficiencies if these scanning deficiencies can be remediated in a training program that does not train motor behavior or remediate attentional deficits. The cause of the improved performance is obviously that older drivers have been made to attend better at intersections; but we do not think this pattern is consistent with what is usually meant by “attending better,” such as increasing mental capacity, expanding the size of the visual field within which one can perceive what is going on, or decreasing the ability of irrelevant stimuli to attract and hold attention. While it is logically possible that this brief training procedure increased something like working memory capacity and had a continuing effect 12 months later, this seems quite implausible. Moreover, as we emphasized earlier, the test scenarios had essentially no “clutter.” There was little competition for the driver’s attention other than controlling the car and paying attention to the roadway directly ahead.

What Is Older Drivers’ Problem at Intersections?

We seem to have eliminated all possible explanations for why older drivers fail to scan at intersections. However, there is another possibility, which we think is a viable working hypothesis: They have developed something akin to an unsafe habit. That is, it is plausible that older drivers take as their goal in driving to be sure not to hit anything that is in front of their vehicle. Thus, they focus on the area of the roadway toward which they are headed and drive more slowly in the event a collision were to occur. That is, they have, over time, come to focus on what they construe as the central driving task: not colliding with a vehicle, pedestrian, or other object in their intended path of travel. This may be because they have—or fear they have—reduced capabilities as drivers.

Such a strategy is adequate for most situations other than intersections. However, in an intersection, the primary threat for the older driver is a vehicle hitting the older driver from the side, not the older driver hitting another vehicle directly in front of him or her. One possible reason that older drivers are unaware that this strategy is unsafe is that crashes are in fact relatively rare, so that they are unlikely to have been given feedback on the nonoptimality of their behavior. Moreover, even if they have had a crash at an intersection, the crash may not have been entirely their fault (e.g., the other vehicle was going too fast), so that they may not realize they made a mistake.

We think it is plausible that such a habit could develop over time: It simplifies life and it seems to work. Moreover, it is consistent with the training data. That is, if a driver is merely told that this failure to scan is a general problem for older drivers, it appears to have no impact on behavior if the particular older driver has little reason to think that it applies to him or her. In contrast, if the training graphically shows drivers how they failed to scan and they are clear that they were missing something important, their scanning behavior is likely to change. We admit that it is amazing that this brief session appears to bring the older drivers back to the level of younger experienced drivers in the same scenarios. However, the older drivers in the experiment may have been better than average older drivers.

Conclusions

Our research has found that a major problem with older drivers is their failure to scan adequately for upcoming potential hazards. This is also a problem for novice drivers (Pollatsek, Fisher, & Pradhan, 2006) and is also remediable with training (Pradhan, Pollatsek, Knodler, & Fisher, 2009). However, unlike with younger drivers, this failure appears to be largely restricted to intersection scenarios—situations in which another vehicle could hit the driver’s vehicle from the side. Both problems appear to be trainable with simple methods that are not expensive. However, it is not plausible that these scanning failures are the sole reason for increased accidents in the older driver population. For example, it is likely that there are older drivers who should not be driving because they have serious vision, motor, or general attentional problems and that this is a factor contributing to the increased accident rates for older drivers. However, there are periodic tests in many states to limit the numbers of such drivers, at least those with vision problems; moreover, there is likely a fair amount of “self-selection” on the part of such drivers. Nonetheless, our data indicate that older drivers who do not suffer from such problems still fail to scan adequately at intersections and that this failure by itself is plausibly a major contributor to the increased crash rate for older drivers.

Acknowledgments

The contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or the Arbella Insurance Charitable Foundation.

Funding

Portions of this research were funded by grants from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (DTNH22-04-H-01421), the National Institutes of Health 1R01HD057153-01), and the National Science Foundation (Equipment Grant SBR 9413733 for the partial acquisition of the driving simulator).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Recommended Reading

- Bao S, Boyle LN. Age-related differences in visual scanning at median-divided highway intersections in rural areas. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2009;41:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.10.007. Study finding that older drivers looked to the left and right less often than did younger and middle-aged drivers at two stop-controlled median-divided intersections with high crash rates. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DD, Ward P, Bartle C, Truman W. Older drivers’ road traffic crashes in the UK. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2010;42:1018–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.12.005. A study finding that intersection collisions (primarily a consequence of visual search problems) and more general failures to yield right of way were the largest single class of crashes in involving older drivers in a large U.K. sample. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollatsek A, Vlakveld W, Kappe B, Pradhan A, Fisher DL. Driving Simulators as training and evaluation tools: Novice drivers. In: Lee JD, Caird J, Fisher DL, Rizzo M, editors. Handbook of driving simulation in engineering, medicine and psychology. Chapter 30. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 1–18. Reviews worldwide studies that have used driving simulators to deliver training to novice drivers and to evaluate the difference between experienced and novice drivers or between trained and untrained novice drivers. [Google Scholar]

- Romoser MRE, Fisher DL. The effect of active versus passive training strategies on improving older drivers’ scanning in intersections. Human Factors. 2009;51:652–668. doi: 10.1177/0018720809352654. A fuller description of most of the experiments described in the current article (although the detailed description of the time course of glances is new to this article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Ball K, Owsley C. Identifying correlates of accident involvement for the older driver. Human Factors. 1991;33:583–595. doi: 10.1177/001872089103300509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Boyle LN. Age-related differences in visual scanning at median-divided highway intersections in rural areas. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2009;41:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitman KA, Kirley BB, Ferguson S, Chaudhary NK. Factors leading to older drivers’ intersection crashes. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2007;8:267–274. doi: 10.1080/15389580701272346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DD, Ward P, Bartle C, Truman W. Older drivers’ road traffic crashes in the UK. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2010;42:1018–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eck RW, Winn G. Older-driver perception of problems at unsignalized intersections and divided highways. Transportation Research Record. 2002;1818:70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Sirén A, Davidse R. Older drivers: A review (VTI Rapport 497A) 2004 Retrieved from http://www.vti.se/sv/publikationer/pdf/aldre-forare--en-oversikt.pdf.

- Isler RB, Parsonson BS, Hansson GJ. Age related effects of restricted head movements on the useful field of view of drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 1997;29:793–801. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollatsek A, Fisher DL, Pradhan AK. Identifying and remediating failures of selective attention in younger drivers. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:255–259. doi: 10.1177/0963721411429459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AK, Pollatsek A, Knodler M, Fisher DL. Can younger drivers be trained to scan for information that will reduce their risk in roadway traffic scenarios that are hard to identify as hazardous? Ergonomics. 2009;62:657–673. doi: 10.1080/00140130802550232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoser MRE. Improving the road scanning behavior of older drivers through the use of situation-based learning strategies. Amherst: Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Massachusetts; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Romoser MRE. The long term effects of active training strategies on improving older drivers’ scanning at intersections (Technical Report, Arbella Insurance Human Performance Laboratory) Amherst: Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Massachusetts; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Romoser MRE, Fisher DL. The effect of active versus passive training strategies on improving older drivers’ scanning in intersections. Human Factors. 2009;51:652–668. doi: 10.1177/0018720809352654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoser MRE, Fisher DL, Mourant R, Wachtel J, Sizov K. The use of a driving simulator to assess senior driver performance: Increasing situational awareness through post-drive one-on-one advisement. Proceeding of the Third International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training and Vehicle Design; Rockport, Maine. Iowa City: University of Iowa Public Policy Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spek ACE, Wieringa PA, Janssen WH. Intersection approach speed and accident probability. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2006;9:155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Radwan E, Guo D. Effects of major-road vehicle speed and driver age and gender on left-turn gap acceptance. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2007;39:843–852. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]