Abstract

Few studies assessed the results of multiple exposures to disaster. Our objective was to examine the effect of experiencing Hurricane Gustav on mental health of women previously exposed to Hurricane Katrina. 102 women from Southern Louisiana were interviewed by telephone. Experience of the hurricanes was assessed with questions about injury, danger, and damage, while depression was assessed with the Edinburgh Depression Scale and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) using the Post-traumatic Checklist. Minor stressors, social support, trait resilience, and perceived benefit had been measured previously. Mental health was examined with linear and log-linear models. Women who had a severe experience of both Gustav and Katrina scored higher on the mental health scales, but finding new ways to cope after Katrina or feeling more prepared was not protective. About half the population had better mental health scores after Gustav than at previous measures. Improvement was more likely among those who reported high social support or low levels of minor stressors, or were younger. Trait resilience mitigated the effect of hurricane exposure. Multiple disaster experiences are associated with worse mental health overall, though many women are resilient. Perceiving benefit after the first disaster was not protective.

Keywords: disaster, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, women

Introduction

Hurricane Katrina (2005) was one of the largest natural disasters ever experienced in the United States, and led to extensive flooding, damage, and loss of life, especially in the New Orleans area. Hurricane Gustav (2008) was a less powerful hurricane; damage was largely limited to wind damage and power outages, with more extensive effects in the mid-Southern Louisiana area, such as around Baton Rouge. Gustav was, however, the first major hurricane to hit the New Orleans area after Katrina, and a mandatory evacuation was called. The effects of evacuation, such as disruptions of schools and jobs, and extensive transportation difficulties, were widespread.

Experiencing a disaster is a known cause of psychopathology (mental illness and distress). It is estimated that disaster increases overall community psychopathology by 17% (Rubonis & Bickman, 1991), while between 5 and 60% of those exposed to a disaster will develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD;(Galea et al., 2005)). The duration of these psychological disorders will vary, with many people showing symptoms only in the short term, while others experience an extended or lifetime mental illness. For instance, Goenjian et al. found that those exposed to severe trauma, including earthquake trauma, had high PTSD scales which did not remit over the next 1–5 years, while depressive symptoms subsided (Goenjian et al., 2000). These patterns were less clear in those exposed to mild earthquake trauma.

Generally, subsequent traumas worsen PTSD and other post-traumatic psychopathology. Initial bad experiences can cause a person to react badly to subsequent events (‘kindling’) (Carver, 1998). A study of refugees found the September 11th terrorist attacks often triggered traumatic responses and symptoms (Kinzie et al., 2002), while emergency room patients in New York exposed to both the 9/11 attacks and a plane crash one year later had worse mental health status and general health if they were exposed to both rather than a single disaster (Fernandez et al., 2005). Exposure to prior traumatic stress was associated with distress after an earthquake (Sattler, de Alvarado, de Castro, Male, et al., 2006). Chronic (rather than remitting) PTSD was associated with experiencing new traumatic events during follow-up in an adolescent/young adult sample (Perkonigg et al., 2005), and several studies have shown that multiple traumatic experiences in childhood and adulthood increase the likelihood of persistent depression in women (Honkalampi et al., 2005; Maciejewski et al., 2001; Tanskanen et al., 2004).

Resilience has been defined as the ability to bounce back or recover from stress (Carver, 1998), and as well as an ability to maintain healthy psychological functioning in the face of highly disruptive events (Bonanno, 2004). Some people are able to face disruptive events and go beyond baseline or maintenance, to actual improvement. This positive change after adversity is often referred to as post-traumatic growth. We refer to a subset of post-traumatic growth, perceived benefits, for the specific situation when a person perceives good things as having arisen from a negative situation (regardless of external perceptions or empirical measures). Resilience has been most studied in a developmental perspective, i.e., children who grow up in difficult circumstances but avoid substance abuse or behavioral problems, do well in school, and achieve education, employment, and stable family life as adults (Garmezy, 1991; Luthar et al., 2000; Masten, 2001; Werner, 1995). However, the concept of resilience can also be applied to experiencing difficult events as an adult. Bonanno et al. (2006), in his studies of the effects of September 11th, operationalized resilience as a lack of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression symptoms and low self-reported alcohol use (Bonanno et al., 2006). Research shows that those with high self-reported hardiness or ego resiliency who are exposed to a difficult circumstance will be less likely to develop depression (Adler & Dolan, 2006; Fredrickson et al., 2003).

Some studies indicate that post-traumatic growth also buffers against mental health problems among those with severe exposures to disasters (McMillen et al., 1997) or sexual assault (Frazier et al., 2001); however, not every study agrees (Sattler, de Alvarado, de Castro, Van Male, et al., 2006). Several other studies show varying degrees of relationship between types of post-traumatic growth and subsequent distress (Linley & Joseph, 2004). A meta-analysis found small negative associations between perceived positive changes after a major negative event (such as major health concerns, bereavement, war, rape, or “major traumatic event” ) and depression, no association with global distress, and positive associations with intrusive-avoidant thoughts (Helgeson et al., 2006). Another review found inconclusive relationships between post-traumatic growth and mental health: generally, studies found a null or negative relationship with depression, and null or positive relationship with distress or anxiety. However, fewer of these studies dealt with disaster (Zoellner & Maercker, 2006).

Bonanno also included “the capacity for generative experiences and positive emotions” in his definition of resilience (Bonanno, 2004), p.20). This implies that resilient people will not only be resistant to psychological distress, but be more apt to experience growth after difficult experiences. At least one study suggests that resilient people are actually less likely to search for meaning after trauma (Westphal & Bonanno, 2007). However, other studies indicate that resilient people will be more likely to experience post-traumatic growth. Experimental studies by Tugade and Fredrickson (2004) showed that high-resilient individuals reported greater positive emotionality and experience faster cardiovascular recovery to a stressor (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). In a non-experimental context, Fredrickson et al. (2003) examined the role of resilience and positive emotions in predicting depression and thriving after 11 September (Fredrickson et al., 2003). They found that resilient people were more likely to thrive (defined as an increase in psychological resources like optimism and tranquility) after the attacks.

In this study, we address mental health in a group of women who had first been exposed to Hurricane Katrina, to varying degrees, and then were exposed to Hurricane Gustav. These women were initially part of a study of postpartum mental health after Katrina. We use this multiply-exposed sample to assess how Hurricane Gustav experience affected the mental health of women already exposed to Hurricane Katrina. We also examined how the experiences of the hurricanes, self-rated trait resilience, and post-traumatic growth predicted resilience after Hurricane Gustav.

Methods

Participants were initially recruited from Tulane Lakeside Hospital, Metairie, LA and Women’s Hospital, Baton Rouge, LA after being admitted for childbirth between March 2006 and May 2007. The two sites were chosen as a strongly-affected area (Metairie is a suburb of New Orleans and was flooded during Hurricane Katrina) and a less-affected area to serve as a comparison group. Both hospitals serve a wide geographic and socioeconomic range from their cities and surrounding areas. Women recruited at the New Orleans site needed to have lived in the New Orleans area before Hurricane Katrina, be 18 or over, speak English, and have access to a telephone. Women in Baton Rouge needed to be 18 or over, speak English, have access to a telephone, and not have had a severe exposure to Katrina (defined as being forced to evacuate or having a relative die). Demographic characteristics were similar between the two sites, except that Baton Rouge women were somewhat more likely to be married or living with a partner (86% vs. 77% in New Orleans) and to have a college education or more (46% vs. 33% in New Orleans).

At recruitment, participants completed a questionnaire (details below). Participants completed a phone interview at approximately 8 weeks postpartum (median time since delivery, 8.9 weeks; median time since hurricane 10.1 months), and a self-administered, mail-delivered questionnaires at 12 months postpartum (median time since the hurricane, 19 months). If a woman did not return the 12-month questionnaire within a month, she received a reminder phone call. If she still did not return it, a brief questionnaire consisting only of the depression and PTSD scales (described below) was sent. 365 women were recruited, 292 completed the phone interview, 172 returned the 12-month questionnaire, and 48 returned the brief 12-month questionnaire only. Those lost to follow-up were more likely to be young, black, or have a lower level of education.

After Hurricane Gustav, IRB approval was received for another round of phone interviews. All women were contacted by telephone during the fall of 2008; interviews were completed with 102 women. Most of those lost to follow-up could not be located by telephone.

All procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Tulane University and Woman’s Hospital.

Measures

Depression

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was used to assess depression among the study participants. The 10-question self-administered scale and has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 78% against a clinical diagnosis(Cox et al., 1987). Subsequent validation studies in general and high-risk populations put sensitivity between 65 and 100% and specificity between 49 and 100% (Eberhard-Gran et al., 2001). The internal consistency of this scale has been found to be good (in pregnant women, Cronbach’s α=0.85; (Dayan et al., 2002). Depression was measured at the 2-month phone interview, the 12-month questionnaire, and the post-Gustav interview.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

PTSD was measured using the PTSD checklist (PCL), a commonly used, 17-item inventory of PTSD-like symptoms, with response alternatives ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) (Weathers et al., 1993; Weathers et al., 1999). Using a 5-point scale, respondents indicate how much they are bothered by each PTSD symptom in the past month. An α of 0.97 and a test-retest reliability of 0.96 have been reported (Weathers et al., 1993; Weathers et al., 1999). PTSD was measured at the 2-month phone interview, the 12-month questionnaire, and the post-Gustav interview.

Hurricane Experience

The hurricane experience score was based on answers to 9 questions, including whether participants ever felt their life was in danger during the storm, if they or a family member became ill or injured as a result of the storm, if they walked through floodwaters, severity of damage to their home and possessions, if anyone close to them died, or if they witnessed anyone die. The scale was based on a previous study of Hurricane Andrew by Kaniasty and Norris (Norris et al., 1999). Based on a factor analysis, these questions were divided into three categories: damage, injury, and perceived/experienced danger. We also created a scale of overall severity of hurricane experience by summing the number of events experienced. Two or more of the listed experiences was considered ‘high hurricane experience’, which was associated with PTSD and depression after Katrina (Harville et al., 2009; Xiong et al., 2010). Hurricane Katrina experience was measured at recruitment. For the Gustav follow-up, we asked the same questions relating to Gustav, as well as questions about the time spent evacuating, the time spent living without power, and the time one’s house was without power, regardless of whether one was living there. A factor analysis did not indicate multiple subfactors, so a simple summary index was also created, summing the number of negative experiences: injury, damage, injury to others, felt life in danger.

Perceived benefit

Perceived benefit was assessed in two ways. First, we asked the woman “Sometimes even the most awful events have their good outcomes, at least in part. Can you think of anything positive that came about as a result of the hurricane?” Next, we asked a series of questions about the respondent’s personal growth, usefulness of previous learning and oral traditions, ability to make new friends, and confidence in the future (Vazquez et al., 2005). Perceived benefit was measured at recruitment.

Resilience

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) was used to assess resilience as the self-perceived ability to bounce back from stress. In undergraduate students, adult women, and heart patients, the BRS has been associated with less anxiety, depression, physical symptoms, and more positive affect (Smith et al., 2008), as well as the ability to habituate to pain stimuli (Smith et al., 2009). The BRS is listed in table S1. The six items (e.g., “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”) were scored on a 5-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The Brief Resilience Scale was administered during the 6–8 week phone interview. In our data, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.83 and in a factor analysis the items loaded on a single factor.

Minor stressors

The Daily Stress Inventory (DSI)(Brantley et al., 1987) is a self-administered scale which features 44 minor but stressful occurrences, such as “Was stared at” and “Had difficulty in traffic”, asks if they occurred in the last 24 hours, and asks the respondent to rank how stressful the experience was. The DSI has been shown to correlate with endocrine measures of stress (Brantley et al., 1988). The effect of such minor stressors, often referred to as “daily hassles”, on well-being is believed to be mediated by both frequency and appraisal of the stressors (Almeida, 2005). A summed scale was created, so that 0=did not occur, 1=occurred but did not cause me stress, and 2 through 7 reflected increasing degrees of stress. This summed score was divided at 50, the upper tertile, to define high daily hassles. The DSI was part of the 12-month questionnaire.

Perceived social support

Social support is defined as assistance and protection received from others, either tangible help (such as money) or intangible (such as emotional support)(Langford et al., 1997). The Support Behaviors Inventory from the Perinatal Psychosocial Profile (PPP) was used to assess perceived social support (Brown, 1986a, 1986b). It includes 11 questions about perceived support, asked first about the woman’s partner and then about support from others. The PPP has been tested on a large, culturally diverse rural and urban pregnant women (Curry et al., 1998). The scale largely assesses emotional and information support, but seems to have an underlying single factor (Brown, 1986a). Internal consistency and reliability was 0.89 for total support in the development study (Brown, 1986a). Low social support was dichotomized as the 25th percentile at the 8-week interview, 50 points. Perceived social support was measured at 6 months post partum.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables. Correlations were calculated among the mental health variables (Spearman correlations were calculated for continuous variables and polychoric/tetrachoric correlations for ordinal and dichotomous variables). Scores on the PTSD and depression scales at 2 months post partum, 12 months post partum, and after Gustav were compared, and categorized into those whose scores improved after Gustav and those who worsened or stayed the same. The relationship between these categories and demographic and hurricane predictors was examined using chi-square tests. Multiple regression models were used to examine the effect of experiencing both Gustav and Katrina on mental health. Models were adjusted for variables associated with mental health: age, race, education, parity, prior mental health status, as well as time between Gustav and the interview. Other demographic factors (marital status, income) did not change effect estimates and so were eliminated from the model. An interaction term was used to allow for different effects in those who had a ‘high’ or ‘low’ experience of Katrina. Finally, we looked at demographic and hurricane-experience predictors of improvement. Log-linear models were used to calculate relative risk of improvement, adjusting for race, education, age, time since Gustav, parity, and baseline mental health.

Results

The study population was three-quarters white, with most having some higher education (Table 1). Mental health after Katrina and Gustav were highly correlated (Table 2). Experiencing danger or injury after Katrina or Gustav were also associated with worse mental health after Gustav, but reporting new ways to cope or feeling more prepared after Katrina were not associated with mental health. Higher trait resilience was associated with lower PTSD and depression symptoms.

Table 1.

Description of the study population

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–22 | 15 | 14.7 |

| 23–28 | 25 | 24.5 |

| 29–33 | 26 | 25.5 |

| 34+ | 36 | 35.3 |

| Race | ||

| white | 75 | 75.0 |

| black | 24 | 24.0 |

| other | 1 | 1.0 |

| Currently pregnant | ||

| yes | 9 | 8.9 |

| no | 92 | 91.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| married | 71 | 70.3 |

| living with partner | 15 | 14.9 |

| divorced | 3 | 3.0 |

| single | 12 | 11.9 |

| Education | ||

| <=HS | 28 | 28.2 |

| some college/AA | 27 | 27.3 |

| >=college | 44 | 44.4 |

| Parity at initial interview | ||

| 1 | 45 | 44.1 |

| 2 | 37 | 36.3 |

| 3+ | 20 | 19.6 |

AA, Associate of Arts (2-year degree)

Table 2.

Correlations among mental health and benefit variables

| PTSD-G | depression-G | |

|---|---|---|

| PTSD-K | 0.72*** | 0.47*** |

| depression -K | 0.54*** | 0.41*** |

| hurricane K - damage | 0.34 | 0.10 |

| hurricane K - injury | 0.29*** | 0.22** |

| hurricane K - danger | 0.40*** | 0.28*** |

| hurricane G - overall | 0.27*** | 0.21** |

| Found new ways to cope after Katrina | −0.10 | 0.05 |

| Felt more prepared to deal with disaster after Katrina | 0.68 | 0.05 |

| Trait resilience | −0.29*** | −0.18* |

G, after Gustav; K, after Katrina; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

Next, we examined the combined effect of experiencing Gustav and Katrina. Generally, feeling one’s life was in danger during Gustav, living without power, and overall severe experience of Gustav were associated with worse mental health after Gustav, and women who had a severe experience of both Gustav and Katrina scored higher on the mental health scales (table 3). However, there was little synergistic interaction between Katrina experience and Gustav experience. The strongest exception seemed to be for time one’s house was without power, which had a stronger effect on mental health among those with a severe Katrina experience.

Table 3.

Effects of Hurricane Gustav experience and Katrina on mental health

| PTSD | depression | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Low Katrina experience | High Katrina experience | Low Katrina experience | High Katrina experience | |||||||||||

| Beta1 | SD | P | Beta | SD | P | p for interaction - Gustav and Katrina experience | Beta1 | SD | P | Beta | SD | P | P for interaction - Gustav and Katrina experience | |

| life in danger2 | 4.9 | 3.50 | 0.15 | 15.1 | 5.60 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 3.7 | 1.72 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 2.75 | 0.98 | 0.26 |

| degree of damage | 3.6 | 3.04 | 0.24 | 10.2 | 6.30 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 1.2 | 1.48 | 0.40 | 4.5 | 3.04 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

| injury to self | 6.1 | 4.25 | 0.15 | 6.7 | 7.91 | 0.40 | 0.95 | 2.5 | 2.05 | 0.22 | 4.2 | 3.70 | 0.26 | 0.69 |

| injury to others | 5.9 | 3.11 | 0.06 | 1.6 | 6.42 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 1.3 | 1.51 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 3.16 | 0.89 | 0.81 |

| time house without power | 4.4 | 2.50 | 0.08 | 19.5 | 5.58 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 1.30 | 0.87 | 6.5 | 1.96 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| time lived without power | 4.8 | 2.91 | 0.10 | 7.6 | 5.80 | 0.19 | 0.66 | −0.4 | 1.28 | 0.78 | 3.9 | 2.50 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| evacuated early | −0.7 | 2.81 | 0.81 | −7.5 | 6.11 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.0 | 1.58 | 1.00 | −5.5 | 3.35 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Gustav summary experience | 1.6 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 4.2 | 1.43 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.5 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 1.2 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.44 |

increase in PTSD or depression scale in those experiencing factor; adjusted for age, race, education, parity, time since Gustav at interview, and prior mental health status.

during Gustav

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

45 (49%) had better PTSD scores than at the 2-month postpartum interview (median time since Katrina, 10 months), while 49 (53%) of the study population had better depression scales. 54 (65%) of the study population had better PTSD scores after Gustav than at the 12-month postpartum interview (median time since Katrina, 19 months), and 48 (58%) had better depression scores. Improvement in PTSD scores since 2 months was less likely among those who experienced an injury during Gustav (adjusted relative risk 0.28, 95% confidence interval 0.08–0.97), and more likely among those who were pregnant (1.81, 1.03–3.17). Improvement in depression scores since 2 months was less likely among those who reported low support from partner (0.56, 0.36–0.87) or high levels of daily hassles (0.64, 0.42–0.96). There was also a trend for the youngest women to be the most likely to show improvement, particularly for depression (p=0.02). Women who reported finding new ways to cope after Katrina were somewhat more likely to show improvement (1.72., 0.85–3.46) in PTSD scores, but not in depression scores (0.75, 0.55–1.01). There were no associations between feeling more prepared for future disasters and improved mental health.

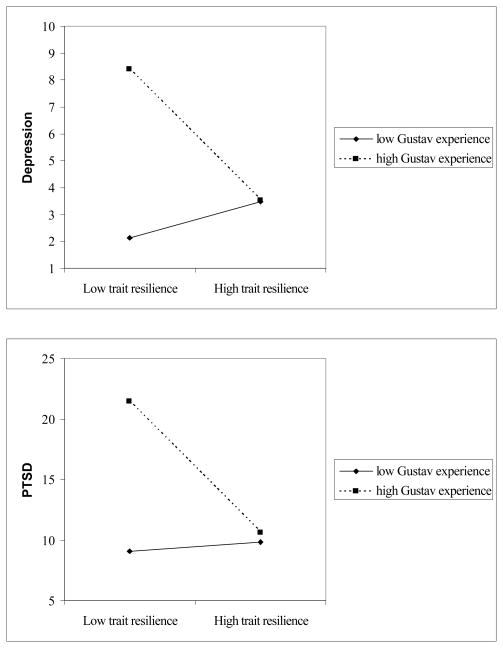

Finally, we examined the relationship between trait resilience and mental health after Gustav. Trait resilience was not a direct predictor of mental health once prior mental health was accounted for, nor did it predict perceived benefit after Gustav. It did, however, interact with some both Katrina and Gustav experiences, indicating that high trait resilience mitigated the effect of the hurricanes on mental health (table 4). Figure 1 shows how trait resilience moderated the effect of Gustav experience of injury on depression and PTSD.

Table 4.

Multiple regression models of trait resilience and hurricane experience predicting mental health.

| depression at 12 months postpartum

|

PTSD at 12 months postpartum

|

depression after Gustav

|

PTSD after Gustav

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta1 | SD | P | beta | SD | P | beta | SD | P | beta | SD | P | ||

| trait resilience | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.26 | −0.57 | 0.23 | 0.01 | trait resilience | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.51 | −0.17 | 0.26 | 0.53 |

| Katrina experience- damage | −1.14 | 3.17 | 0.72 | −11.36 | 6.66 | 0.09 | Gustav experience- damage | 2.13 | 1.41 | 0.13 | 4.99 | 2.90 | 0.09 |

| baseline mental health | 0.63 | 0.08 | <.01 | 0.55 | 0.07 | <.01 | baseline mental health | 0.45 | 0.12 | <0.01 | 0.64 | 0.10 | <.01 |

| Katrina experience – damage *trait resilience | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.03 | Gustav experience*trait resilience | −0.27 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.84 |

| trait resilience | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.77 | −0.38 | 0.20 | 0.06 | trait resilience | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.82 |

| Katrina experience - injury | 4.39 | 3.40 | 0.20 | 2.70 | 1.84 | 0.14 | Gustav experience - injury | 3.22 | 1.77 | 0.07 | 6.80 | 3.75 | 0.07 |

| baseline mental health | 0.61 | 0.08 | <.01 | 0.58 | 0.07 | <.01 | baseline mental health | 0.41 | 0.11 | <0.01 | 0.63 | 0.10 | <.01 |

| Katrina experience*trait resilience | −0.11 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 0.13 | Gustav experience*trait resilience | −0.65 | 0.33 | 0.05 | −1.21 | 0.70 | 0.08 |

| trait resilience | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.42 | −0.03 | 0.22 | 0.89 | trait resilience | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.39 |

| Katrina experience - danger | 7.11 | 3.15 | 0.02 | 1.80 | 1.58 | 0.26 | Gustav experience - danger | 0.41 | 0.12 | <0.01 | 0.61 | 0.09 | <.01 |

| baseline mental health | 0.66 | 0.08 | <.01 | 0.57 | 0.07 | <.01 | baseline mental health | 2.67 | 1.51 | 0.08 | 6.16 | 3.01 | 0.04 |

| Katrina experience- danger*trait resilience | −0.33 | 0.14 | 0.02 | −0.44 | 0.31 | 0.15 | Gustav experience- danger*trait resilience | −0.15 | 0.32 | 0.64 | −1.38 | 0.63 | 0.03 |

Models adjusted for age, education, parity, and race. Gustav models also adjusted for time since Gustav. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

Figure 1.

Interaction of trait resilience with experience of injury during Hurricane Gustav.

Discussion

This analysis explored the question of whether some people react more or less strongly to a disaster after having been exposed to a prior disaster, and what predicts this. Consistent with many previous studies, mental health was worst in those who experienced the most trauma (Honkalampi et al., 2005; Tanskanen et al., 2004). However, we did not find that mental health was worse than would be expected given the independent effect of the storm. A study of adolescent female offenders found that pre-hurricane family stressors and Katrina-related stressors independently predicted depression. (Robertson et al., 2009). In addition, approximately one-half of the women scored better on PTSD and depression scales than after a previous disaster. Younger women seemed to be more likely to improve, as did those who reported lower levels of minor stressors after Katrina. We also found that those who reported high social support after Katrina were more likely to have improved mental health after Gustav. This is consistent with other studies which have found that pre-disaster support improves readiness, reduces exposure, and improves mental health (Lowe et al., 2010)(Heller et al., 2005).

Many women reported finding new ways to cope or feeling more prepared after Katrina, but these did not seem to translate into improved mental health after Gustav. Disaster survivors often report that the experience of prior trauma helps them deal with later ones. For instance, women who had experienced prior traumas felt the experience helped them cope with the terrorist attacks of 9/11(Thomas, 2003), and focus groups of Vietnamese-Americans exposed to Hurricane Katrina also reported resilience, and that family support was sufficient to buffer any problems associated with the hurricane (Chen et al., 2007). However, in this later study, prior trauma exposure was somewhat associated with poorer physical and mental health. As we have suggested in previous work, it seems that mental health and post-traumatic growth are two different axes of response to disaster (Harville et al., 2010) Higher trait resilience somewhat mitigated the effects of the hurricanes on mental health. This is consistent with studies that show high resilience or similar constructs like hardiness are associated with better mental health (Adler & Dolan, 2006; Wickrama & Wickrama, 2008), and that resilience serves as a resource that protects against mental illness. We did not find that trait resilience was associated with later post-traumatic growth, as other studies have indicated (Westphal & Bonanno, 2007).

Strengths of the study include the longitudinal follow-up and validated instruments for measuring mental health. Limitations include the loss to follow-up in the original study population. Although the original sampling frame was systematic and fairly unselected with respect to mental health, loss to follow-up was greatest in the women most exposed to Katrina. Katrina hit those with few resources, particularly African-Americans, most strongly, and this loss limits the generalizability of our findings. Problems with evacuation, for either Katrina or Gustav, were also most likely for those with limited financial or social resources (Brodie et al., 2006; Eisenman et al., 2007; Elder et al., 2007). In addition, this is a follow-up study to an initial exploration of post-partum mental health after disaster. Severe post-partum depression most commonly declines after the first year, although some women show chronic severe or mild depression.(Ashman et al., 2008; Monti et al., 2008) Women who experience postpartum depression are at up to six times the risk of later depressive episodes (Josefsson & Sydsjo, 2007); follow-up indicates that most long-term cases represent pre-existing cases of depression rather than a long-term, postpartum-related depression (Najman et al., 2000). Therefore, our results comparing mental health at 12 months postpartum are likely to be more generalizable to other populations of women than our results at 2 months. Studies of PTSD in post-partum women are limited and have generally been focused on PTSD related to the birth experience; they have found relative stability in the proportion of women meeting PTSD criteria across the first year (2–3%)(Maggioni et al., 2006; Soderquist et al., 2006; White et al., 2006).

In conclusion, we find that multiple disaster exposures are associated with worse mental health, but that some people do have comparatively better mental health after a second stressful experience than the first. Low social support and higher daily hassles between the stressful experiences may contribute to worse mental health. Self-reported trait resilience mitigates the effect of some distressing experiences on mental health. Future research should try to identify factors that can be intervened on, in order to encourage resilience in the face of disaster.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

Multiple experiences of disaster are associated with worse mental health.

On the other hand, some women who are exposed to multiple disasters have better mental health after the second than the first.

Women who have low social support and high levels of daily hassles are less likely to be resilient when exposed to a later disaster.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R21 MH078185-01 and the Tulane Research Enhancement grants (Phase II).

Dr. Harville was supported by Grant Number K12HD043451 from the National Institute of Child Health And Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health

References

- Adler AB, Dolan CA. Military hardiness as a buffer of psychological health on return from deployment. Military Medicine. 2006;171:93–98. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ashman SB, Dawson G, Panagiotides H. Trajectories of maternal depression over 7 years: Relations with child psychophysiology and behavior and role of contextual risks. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:55–77. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. Psychological resilience after disaster: New York City in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attack. Psychological Science. 2006;17:181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley PJ, Dietz LS, McKnight GT, Jones GN, Tulley R. Convergence between the Daily Stress Inventory and endocrine measures of stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:549–551. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley PJ, Waggoner CD, Jones GN, Rappaport NB. A Daily Stress Inventory: development, reliability, and validity. J Behav Med. 1987;10:61–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00845128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M, Weltzien E, Altman D, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Experiences of hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston shelters: implications for future planning. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1402–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MA. Social support during pregnancy: a unidimensional or multidimensional construct? Nurs Res. 1986a;35:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MA. Social support, stress, and health: a comparison of expectant mothers and fathers. Nurs Res. 1986b;35:72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages. Journal of Social Issues. 1998;54:245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Keith VM, Leong KJ, Airriess C, Li W, Chung KY, et al. Hurricane Katrina: prior trauma, poverty and health among Vietnamese-American survivors. Int Nurs Rev. 2007;54:324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry MA, Burton D, Fields J. The Prenatal Psychosocial Profile: a research and clinical tool. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:211–219. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199806)21:3<211::aid-nur4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan J, Creveuil C, Herlicoviez M, Herbel C, Baranger E, Savoye C, et al. Role of anxiety and depression in the onset of spontaneous preterm labor. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:293–301. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Samuelsen SO. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:243–249. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman DP, Cordasco KM, Asch S, Golden JF, Glik D. Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(Suppl 1):S109–115. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder K, Xirasagar S, Miller N, Bowen SA, Glover S, Piper C. African Americans’ decisions not to evacuate New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina: a qualitative study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(Suppl 1):S124–129. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez WG, Galea S, Miller J, Ahern J, Chiang W, Kennedy EL, et al. Health status among emergency department patients approximately one year after consecutive disasters in New York City. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:958–964. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Conlon A, Glaser T. Positive and negative life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1048–1055. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, Larkin GR. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2005;27:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Resilience and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. American Behavioral Scientist. 1991;34:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, Najarian LM, Fairbanks LA, Tashjian M, Pynoos RS. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:911–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Xiong X, Buekens P, Pridjian G, Elkind-Hirsch K. Resilience after hurricane Katrina among pregnant and postpartum women. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Xiong X, Pridjian G, Elkind-Hirsch K, Buekens P. Postpartum mental health after Hurricane Katrina: A cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich PL. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller K, Alexander DB, Gatz M, Knight BG, Rose T. Social and Personal Factors as Predictors of Earthquake Preparation: The Role of Support Provision, Network Discussion, Negative Affect, Age, and Education. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2005;35:399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Haatainen K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Tanskanen A, Viinamaki H. Adverse childhood experiences, stressful life events or demographic factors: which are important in women’s depression? A 2-year follow-up population study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:627–632. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson A, Sydsjo G. A follow-up study of postpartum depressed women: Recurrent maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior after four years. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2007;10:141–145. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie JD, Boehnlein JK, Riley C, Sparr L. The effects of September 11 on traumatized refugees: reactivation of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:437–441. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford CP, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SR, Chan CS, Rhodes JE. Pre-hurricane perceived social support protects against psychological distress: a longitudinal analysis of low-income mothers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:551–560. doi: 10.1037/a0018317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG, Mazure CM. Sex differences in event-related risk for major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:593–604. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni C, Margola D, Filippi F. PTSD, risk factors, and expectations among women having a baby: A two-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;27:81–90. doi: 10.1080/01674820600712875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56:227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, Smith EM, Fisher RH. Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:733–739. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti F, Agostini F, Marano G, Lupi F. The course of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first 18 months postpartum in an Italian sample. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2008;11:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Andersen MJ, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Postnatal depression-myth and reality: maternal depression before and after the birth of a child. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:19–27. doi: 10.1007/s001270050004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Perilla JL, Riad JK, Kaniasty K, Lavizzo EA. Stability and change in stress, resources, and psychological morbidity: who suffers and who recovers: Findings from Hurricane Andrew. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1999;12:363–396. doi: 10.1080/10615809908249317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A, Pfister H, Stein MB, Höfler M, Lieb R, Maercker A, et al. Longitudinal Course of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in a Community Sample of Adolescents and Young Adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1320–1327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AA, Morse DT, Baird-Thomas C. Hurricane Katrina’s impact on the mental health of adolescent female offenders. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2009;22:433–448. doi: 10.1080/10615800802290634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubonis AV, Bickman L. Psychological impairment in the wake of disaster: the disaster-psychopathology relationship. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:384–399. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler DN, de Alvarado AM, de Castro NB, Male RV, Zetino AM, Vega R. El Salvador earthquakes: relationships among acute stress disorder symptoms, depression, traumatic event exposure, and resource loss. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:879–893. doi: 10.1002/jts.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler DN, de Alvarado AMG, de Castro NB, Van Male R, Zetino AM, Vega R. El Salvador earthquakes: Relationships among acute stress disorder symptoms, depression, traumatic event exposure, and resource loss. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:879–893. doi: 10.1002/jts.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Tooley EM, Montague EQ, Robinson AE, Cosper CJ, Mullins PG. The role of resilience and purpose in life in habituation to heat and cold pain. Journal of Pain. 2009;10:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderquist J, Wijma B, Wijma K. The longitudinal course of post-traumatic stress after childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;27:113–119. doi: 10.1080/01674820600712172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen A, Hintikka J, Honkalampi K, Haatainen K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Viinamaki H. Impact of multiple traumatic experiences on the persistence of depressive symptoms--a population-based study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2004;58:459–464. doi: 10.1080/08039480410011687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. None of us will ever be the same again: reactions of American midlife women to 9/11. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24:853–867. doi: 10.1080/07399330390244266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez C, Cervellon P, Perez-Sales P, Vidales D, Gaborit M. Positive emotions in earthquake survivors in El Salvador (2001) Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:313–328. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the 9th Annual Conference of the International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the clinician-administered posttraumatic stress disorder scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE. Resilience in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M, Bonanno GA. Posttraumatic growth and resilience to trauma: Different sides of the same coin or different coins? Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2007;56:417–427. [Google Scholar]

- White T, Matthey S, Boyd K, Barnett B. Postnatal depression and post-traumatic stress after childbirth: Prevalence, course and co-occurrence. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2006;24:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KA, Wickrama KA. Family context of mental health risk in Tsunami affected mothers: findings from a pilot study in Sri Lanka. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:994–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Harville EW, Mattison DR, Elkind-Hirsch K, Pridjian G, Buekens P. Hurricane Katrina experience and the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among pregnant women. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5:181–187. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2010.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner T, Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology - a critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.