Abstract

Hydroxyl radicals (OH˙) are involved in the pathogenesis of reperfusion injury and are observed in acute heart failure, stroke, and myocardial infarction. Two different subcellular defects are involved in the pathogenesis of OH˙ injury, deranged calcium handling, and alterations of myofilament responsiveness, but their temporal impact on contractile function is not resolved. Initially, after brief OH˙ exposure, there is a corresponding marked increase in diastolic calcium and diastolic force. We followed these parameters until a new steady-state level was reached at ∼45 min post-OH˙ exposure. At this new baseline, diastolic calcium had returned to near-normal, pre-OH˙ levels, whereas diastolic force remained markedly elevated. An increased calcium sensitivity was observed at the new baseline after OH˙-induced injury compared with the pre-OH˙ state. The acute injury that occurs after OH˙ exposure is mainly due to calcium overload, while the later sustained myocardial dysfunction is mainly due to the altered/increased myofilament responsiveness.

Keywords: contractile function, calcium overload, ischemia, oxygen radicals

reperfusion injury is a serious pathological process that occurs when myocardium is reoxygenized after a period of partial or complete ischemia. Oxygen free radicals occurring during reperfusion injury have been implicated in the pathogenesis of myocardial stunning and in the progression of heart failure. Hydroxyl radicals (OH˙) are one of the most aggressive species of oxygen free radicals that attack many molecules in the human body (11, 42). These OH˙ are involved in the pathogenesis of ischemia-reperfusion injury, commonly observed in numerous clinical situations, including acute heart failure, stroke, and myocardial infarction.

It is documented that multiple subcellular defects contribute to the development of acute myocardial dysfunction, predominantly intracellular calcium overload and alteration in myofilament responsiveness. Previous studies have demonstrated that, after acute exposure of OH˙, intact contracting cardiac trabeculae from mouse, rat, rabbit, and dog develop a rigorlike contracture marked by an increase in diastolic tension, myofilament proteolysis, and overall decreased cardiac contractility, followed by partial recovery (15, 16, 42). Although the phenotype of the acute injury response is well documented, the underlying mechanism and the relative importance of deranged calcium handling vs. altered myofilament function remains incompletely understood. Hence, the goal of this study is to delineate, in a time-resolved manner, the contribution of altered calcium handling and altered myofilament responsiveness throughout the various stages of experimental ischemia-reperfusion injury.

There are multiple mechanisms that are possibly responsible for calcium overload: sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) damage, mitochondrial damage, changes in properties of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), and L-type channel properties have all been implicated to play a (partial) role (4, 8, 11, 14, 16, 22, 42). The relative contributions of these factors, specifically to what extent and how they relate to the sustained damage observed after OH˙ exposure, are still unknown. It is known that impaired SR function is one of the main pathways through which calcium overload is mediated. Previous studies have shown that there is a direct impairment of SR function due to OH˙ exposure, and sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) overexpression can reduce the OH˙-induced contractile dysfunction in murine myocardium, whereas decreased SERCA activity aggravates this injury (10, 16, 37). These studies clearly indicate that calcium overload plays a significant role in cardiac dysfunction due to OH˙-induced processes. Previous studies also showed that OH˙ exposure can lead to the proteolysis of different subunits of troponin in different species (42). Although intracellular calcium overload is present, myofilament alterations may be the primary cause of contractile dysfunction by OH˙ exposure. The goal of this study is to understand the relative magnitude by which myofilament responsiveness, on one hand, and deranged calcium handling (increased diastolic calcium levels and reduced calcium transient amplitude), on the other, impair cardiac contractility after acute OH˙ exposure. In this study, we have focused on the possible interactions of these two mechanisms at different time points of ischemia-reperfusion injury to test our hypothesis that calcium overload plays a major role during acute/early OH˙-induced injury, and that an altered myofilament response occurs in the sustained/later part of the OH˙-induced injury. Elucidating the relative importance of these two distinctly different injury pathways at various stages throughout the injury window will provide crucial insight toward targeting hypothesis-driven novel treatment strategies for oxidative stress injury in the heart. Our results show that calcium overload is mainly responsible for acute diastolic dysfunction after OH˙-induced injury, while sustained myocardial dysfunction is primarily due to the alterations in myofilament responsiveness.

METHODS

Preparation of trabeculae and overall protocol.

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). Additionally, all protocols were approved in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Ohio State University. New Zealand White rabbits (2 kg, ∼3 mo old) were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg iv pentobarbital sodium and injected with 5,000 U/kg heparin. The heart was rapidly removed and perfused retrogradely through the aorta with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) solution containing the following (in mmol/l): 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 20 NaHCO3, 0.25 Ca2+, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4) in equilibrium with 95% O2/5% CO2 at body temperature (37°C). Additionally, 20 mmol/l 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM) was added to the dissection solution to stop the heart from beating and to prevent damage during dissection (19, 28, 29). The effects of BDM, after brief exposure, have been found to be reversible (19, 28). Suitable trabeculae from the right ventricle were dissected carefully, without touching the central part of the muscle, and mounted in a bath. In addition to the muscle, the dissected specimen contained a small portion of tricuspid leaflet attached to one end and a block of tissue from the right ventricular free wall attached to the other end, to facilitate mounting the muscle onto the experimental setup (7, 18, 21, 24, 38). Only thin muscles were used for the study, with a maximum diffusion distance of 100 μm to the core, so core hypoxia would be avoided and not affect the outcome of the results (31). Using a dissection microscope, muscles were mounted in the chamber. The piece of tricuspid valve leaflet was connected to a hook-like extension of micromanipulator, and the cube of ventricular tissue rested in a platinum-iridium, basket-shaped extension of the force transducer. By using this method, we can minimize the end-damage compliance of the muscle and prevent excessive loss of force throughout the experimental protocol (7, 21, 22, 38). The muscle was bathed in a continuous flow of oxygenated KH solution (without the BDM). The muscle was stimulated at 2 Hz, at a temperature of 37°C. The calcium concentration was raised to 1.5 mM, and the muscle stretched until maximal developed force (Fdev) was attained. This length is comparable to maximally attainable length in vivo at the end of diastole (around 2.2 μm sarcomere length) (32). After the stabilization of contractile parameters (15–20 min), we exposed the muscle to OH˙ for 2 min. Twitch contractions were monitored until the transient acute dysfunction had subsided, and diastolic force (Fdia) and Fdev had reached their new steady state (typically 45 min after OH˙ exposure).

Intracellular calcium measurements.

After the stabilization of contractile parameters, we stopped the stimulation, and trabeculae were iontophoretically loaded with bis-fura-2 (Texas Fluorescence), as described previously (2, 17, 21). As bis-fura-2 is a ratiometric dye, it automatically cancels out confounding variables, such as variable dye concentration due to leakage or inactivation of dye by radicals, motion artifacts, and cell thickness. Bis-fura-2, rather than the more commonly used fura-2, was chosen for its higher signal-to-calcium buffering ratio (allowing for a loading of the dye to 5–10 times background without impacting buffering), its slightly higher Kd (390 nM in vitro) than fura-2, which allows for accurate diastolic calcium values and a better resolution at higher intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), and the speed of the indicator (27). Iontophoretic loading of the dye was performed at room temperature (at body temperature, the rate of dye leak is higher). We loaded the bis-fura-2 until the photomultiplier output at baseline 380 nm excitation was between 6 and 10 times over background. After loading and spreading of the dye was completed at room temperature, the system was returned to 37°C. The muscle was stimulated to contract at 2 Hz, while force and fluorescent emission measurements (excitation, 340 and 380 nm) were recorded for the duration of the experimental protocol.

OH˙ exposure.

After the stabilization of contractile parameters, we exposed the muscle to OH˙ for 2 min and measured force and fluorescence (excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm). Contractions were monitored until Fdia and Fdev reached their new steady state (typically 45 min). In this study, OH˙ was produced via the Fenton reaction through H2O2 + Fe3+-NTA (ferric nitrilotriacetic acid) system (42): H2O2 + Fe2+ → Fe3+ + HO− + HO.

The reaction involves hydrogen peroxide and a ferrous iron as a catalyst. The concentration of the H2O2 and Fe-NTA in the organ bath is 3.75 mM and 10 μM, respectively. Previous studies utilizing the fenton reaction have been conducted with H2O2 concentration from 1–10 mM (23). This produces an amount of OH˙ that is comparable to those that occur in ischemia-reperfusion injury (42, 43). As the half-life of OH˙ is short, H2O2 was infused via a separate line feed directly into the organ bath at the level of the muscle. This ensured that OH˙ formation took place directly in the muscle and muscle bath where H2O2 meets Fe-NTA. We also performed control experiments by exposing these muscles to either H2O2 or Fe-NTA alone. In agreement with previous studies (42, 43) using this protocol, exposure to H2O2 alone, or Fe-NTA alone, did not cause any significant change in the contractile parameters, suggesting that the contractile dysfunction is specifically due to the formation of radicals, and not H2O2 or Fe-NTA (23). Hence, this type of protocol reflects an OH˙-mediated injury.

Potassium contractures.

To obtain levels of steady-state force development, which are needed to construct the steady-state force-[Ca2+]i relationship, we wanted to tetanize cardiac muscle reversibly while measuring calcium under physiological conditions. At room temperature, cardiac muscle can be tetanized by rapidly pacing the muscle (at 15 Hz) in the presence of SR-inhibiting drugs. However, at a physiological temperature, even at pacing rates as fast as 20 Hz, healthy, well-perfused muscles almost fully relax at each beat. We thus resorted to K+ contractures before and after OH˙-induced injury to obtain levels of steady-state force development, which are needed to construct the steady-state, force-[Ca2+]i relationship. After ionophoretically loading right ventricular trabeculae with bis-fura 2, the superfusion solution was switched to a modified solution containing (in mM) 142 KCl, 0 NaCl, and 3 CaCl2. Because of the very thin size of trabeculae, fast diffusion of dye, and slowly forming contracture, all of the myocytes in the muscle tissue should eventually depolarize. The rest of the contents of this K+ solution were identical to that of the normal KH buffer. Excitation wavelengths were switched back and forth between 340 and 380 nm so that the 340-to-380 ratio could be taken at given points during the contracture. The high K+ solution was applied for 20 s and then washed out. We plotted the curve between excitation ratio and force to the peak of K+, which was typical of a myofilament calcium sensitivity curve.

Myofilament enrichment sample preparation.

For proteomic studies, muscles were prepared separately as previously described. Because muscles had to be flash frozen, for this particular analysis, muscles were not incubated with calcium indicator dye. To determine potential alterations in myofilament proteins [troponin T (TnT), troponin I (TnI), myosin light chain 2 (MLC-2), myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C), and actin], phosphorylation status of individual trabeculae, treated with either hydrogen peroxide and Fe-NTA or Fe-NTA alone, were homogenized by glass mortar and pestal in a solution containing the following: 75 mM KCl, 10 mM imidazole (pH 7.2) 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM NaN3 (3). As previously mentioned, treatment with Fe-NTA or H2O2 alone produced no alteration in contractile function; thus either can be used as an untreated control (34, 35). Solutions were modified with the addition of 1% Triton, depending on homogenization step. After homogenization, protein pellets were resuspended in sample buffer containing the following: 6% SDS, 0.3% bromophenol blue, 30% glycerol, 150 mM Tris·HCl, and 15 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Before loading, samples were heated to 80°C and centrifuged.

ProQ phospho-protein stain and SYPRO ruby stain.

To determine phospho-protein levels, a ProQ phospho-stain and a SYPRO Ruby protein gel stain (from Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, and Fluorotechnics) was used (26). Briefly, protein samples were run on a 200:1 bis-acrylamide gel at 12%, with a stacking of 4% 29:1 bis-acrylamide concentration. ProQ and SYPRO staining was performed according to standard protocols (Invitrogen). Fluorescent imaging was done using Typhoon imagining (GE). Protein levels were normalized to SYPRO Ruby levels for each individual muscle. Data are expressed as a ratio of phospho-protein to total protein levels and as means ± SE.

Data analysis and statistics.

Data were collected and analyzed on- and offline using custom-written software in LabView (National Instruments). Data are expressed as means ± SE, unless otherwise stated. Data were statistically analyzed using ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc test where applicable or Student's t-tests (paired or unpaired) where applicable. A two-tailed value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Contractile function after OH˙ exposure.

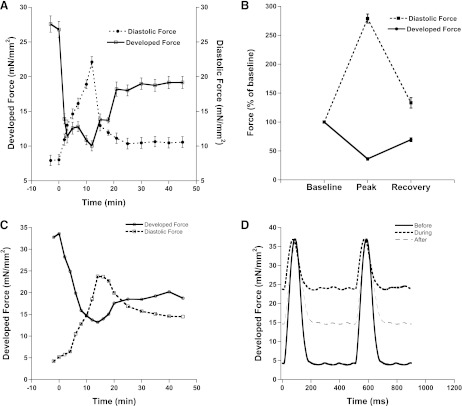

In accordance with previous studies in other species, acute OH˙ exposure in rabbit trabeculae muscles led to a rapid increase in Fdia and a decrease in Fdev. Figure 1A shows the effect on Fdia and Fdev for (n = 10) trabeculae after the exposure of OH˙ in rabbit trabeculae. Contractile parameters were observed for 45 min until a new steady-state level was reached. This new steady-state level was marked by an elevated Fdia and reduced Fdev, compared with pre-interventional values.

Fig. 1.

A: effect of 2-min exposure of hydroxyl radicals (OH˙) on the contractile parameters of cardiac trabeculae (n = 10). Values are means ± SE. B: percentage effect of OH˙ on the contractile parameters of cardiac trabeculae (n = 10). At peak of contracture (occurring at ∼12 min after OH˙ exposure), there is significant increase in diastolic force and a decrease in developed force. New steady state was marked by significant elevated diastolic force and reduced developed force. Values are means ± SE. C: representative tracing developed and diastolic force of one muscle (101013_3) before and after treatment show similar effects to average data. D: representative twitch tracings for one muscle taken before, during, and after treatment with OH˙. Stimulation frequency was 2 Hz and temperature was 37°C throughout the experiment.

Fdia at the peak of contracture (∼12 min after OH˙ exposure) was increased to 279 ± 8% (P < 0.05) of its value before OH˙ exposure and, after ∼45 min, returned to a new steady-state level of 133 ± 9% (P < 0.05). Fdev at peak of contracture was decreased drastically to 36 ± 2% (P < 0.05) and returned to a new steady state level of 70 ± 3% (P < 0.05). Figure 1D shows a representative tracing of an individual muscle before, during, and after the recovery following treatment with H2O2 and Fe-NTA. In another set of control experiments, contractile parameters remained unchanged when muscles were treated similarly but without OH˙ formation for the equivalent period of time (data not shown). These control experiments indicate reliability and durability of the preparation, as well as showing that prolonged study of these isolated trabeculae is not complicated by an excessive loss of function over time. There was no change in contractile parameters in control experiments (data not shown) with either H2O2 alone or with Fe-NTA alone, confirming that formation of OH˙ occurs only when H2O2 with Fe-NTA react, and that this OH˙ is the initiator of the injury response.

Elevated Fdia and a reduced Fdev at the new steady-state level were also accompanied by a slower relaxation: Fig. 2 shows that 50% relaxation time (RT50) and time from 50% relaxation to 90% relaxation (RT90-RT50) were significantly slower after OH˙-induced injury, compared with before injury. Figure 2C shows a representative tracing for RT50 and RT90 of an individual muscle. It is important to remember that, following induction of the OH˙-induced contracture, the RT50 and RT90 are not always visible due to extreme dysfunction of the contracting muscle. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in time to peak tension and another often-used index of contractility and relaxation, the first derivative of force, between the two groups (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Time from peak tension to 50% relaxation (RT50; A) and time from 50% relaxation to 90% relaxation (RT90-RT50; B) before and after OH˙-induced injury are significantly different. At baseline frequency of 2 Hz, RT50 and RT90-RT50 are significantly longer after injury compared with before frequency. Values are means ± SE. *Difference of P < 0.05 between conditions in the same group. C: representative recording of relaxation kinetics from individual muscle (101013_3).

Force-frequency relationship.

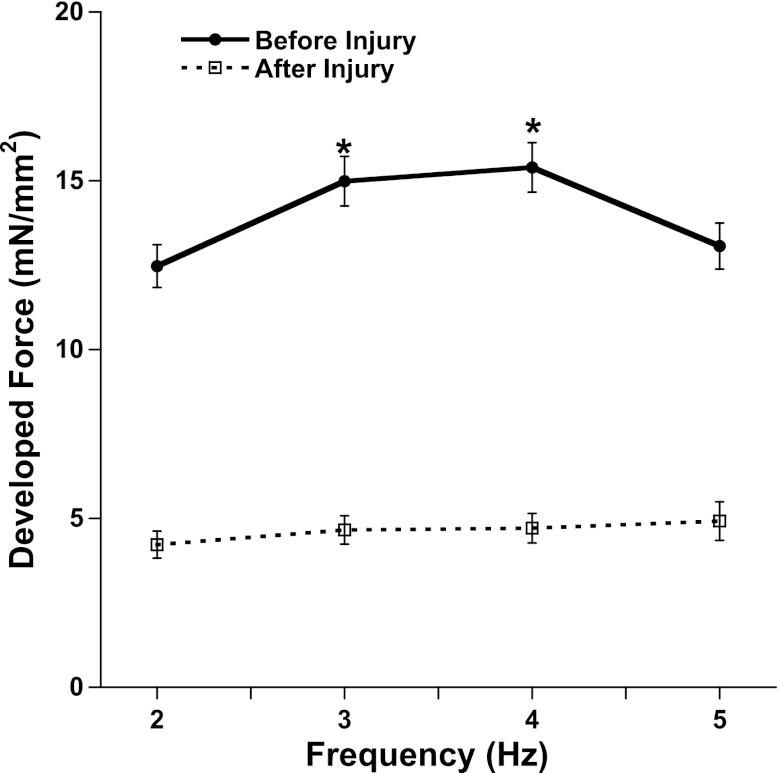

It is known that the activity of the SR calcium-ATPase is reduced by free oxygen radicals. An important aspect for characterizing SR function is the deviation of the force frequency relationship from the normal positive staircase. Figure 3 not only shows that there is a significant decrease in Fdev after OH˙-induced injury at all frequencies, but also that the increase in Fdev from 2 to 4 Hz before injury is significant (P < 0.05), compared with after injury. An increase in stimulation frequency from 2 to 5 Hz induced an increase in Fdev before exposure (this is a normal, positive response) but after OH˙ exposure, there is an attenuation of this positive force-frequency relationship. Force-frequency measurements were performed in rabbit trabeculae before and after 45 min past the OH˙ exposure using the same experimental setup. The long stabilization period inevitably induced some run-down in force (5, 12, 20), and these experiments were performed at a slightly lower extracellular calcium concentration, 1.25 mM Ca2+, the combination of which caused a lower baseline force than the group in Fig. 1.

Fig. 3.

Force-frequency relationship before (following 45 min of 2-Hz stabilization) and after 2 min of OH˙ exposure on RV trabeculae (n = 8). The new steady state was marked by the flat force-frequency relationship compared with positive force-frequency relationship (*P < 0.05) before application of OH˙. Values are means ± SE.

Role of intracellular calcium overload in OH˙-induced injury.

To delineate the temporal resolution of the impact of intracellular calcium overload during OH˙-induced injury, we measured the diastolic level, developed amplitude, and kinetics of calibrated intracellular Ca2+ transients and twitch contractions simultaneously, using ionophoretically loaded bis-fura-2. Figure 4 shows the relationship between intracellular cytosolic calcium and Fdia after the exposure of OH˙ in rabbit trabeculae. Direct acute exposure of OH˙ resulted in an increase in diastolic calcium (on average, from 137 to 779 nM) that occurred in parallel to the increase in Fdia (on average, from 6.2 to 46.4 mN/mm2). Contractile parameters were observed until a new steady-state level was reached. At this new steady-state level, diastolic calcium returned to near-normal levels, whereas Fdia remained significantly elevated compared with pre-interventional values.

Fig. 4.

A: relationship between intracellular calcium and diastolic force after the exposure of OH˙ in right ventricular rabbit trabeculae. Raw record of diastolic force and intracellular calcium before, during, and after exposure to OH˙ (from one experiment) are shown. B: percentage effect of OH˙ on the intracellular calcium and diastolic force (n = 8). At peak of contracture (occurring at ∼12 min after OH˙ exposure), there is a significant increase in diastolic force and a decrease in diastolic calcium. New steady state was marked by a significant elevated diastolic force, but diastolic calcium returned to near pre-interventional values. Values are means ± SE.

Role of myofilament calcium sensitivity in OH˙-induced injury.

The elevated tension, in the absence of significantly elevated calcium, could be partially explained by an increase in the sensitivity of the myofilament for calcium and partially to the development of rigor tension. We assessed myofilament calcium sensitivity, directly, through the use of potassium contractures. To elucidate the impact of altered myofilament responsiveness on sustained injury, we tracked [Ca2+]i (via bis-fura-2 ratio) and force throughout potassium contractures before and after OH˙-induced injury. Figure 5A shows the raw force-calcium data from a single experiment. A leftward shift of the sensitivity curve from before to after OH˙-induced injury was observed. Although the impact of OH˙ exposure on maximal force varies from muscle to muscle, on average, maximal forces were slightly elevated but not significantly different. Cooperativity (Hill coefficient) was likewise unaffected by OH˙ exposure. Figure 5B shows that, on average, there is a disproportional increase in force for a given calcium concentration and suggests that a sensitization of the myofilaments is responsible for the sustained increase in Fdia at the new steady state, after OH˙-induced injury.

Fig. 5.

A: assessment of myofilament responsiveness before (following 45 min of 2-Hz stabilization) and after the OH˙-induced injury. Using the K+ contracture protocol, a steady-state force-Ca2+ concentration relationship was measured before and after OH˙-induced injury. This shows that the curve shifts up and left after the injury. B: EC50 decreased after OH˙-induced injury. *Difference at P < 0.05 between conditions in the same group. On average, neither maximal force nor cooperativity (Hill coefficient) was significantly different (not shown). Values are means ± SE.

OH˙ induced alterations in phosphorylation level of key myofilament proteins.

During ischemic events, it is common to observe an increase in phosphorylation of TnI and TnT (39). In an attempt to better understand the effects of reperfusion injury, and the observed myofilament calcium sensitization, alterations in phosphorylation status of myofilament proteins was assessed. To determine if OH˙ induced alterations at the myofilament level, during reperfusion, ProQ phospho-protein stain and SYPRO Ruby total protein stain analyses were conducted on treated (n = 5) and untreated (n = 5) trabeculae (Fig. 6). Muscles were treated with either Fe-NTA (untreated for 45 min) or H2O2 + Fe-NTA (treated for 2 min and allowed to stabilize the remaining 43 min) and were analyzed for alterations in MyBP-C, TnT, TnI, and MLC-2 phosphorylation status. Figure 6, B and C, shows a representative blot of treated vs. untreated trabeculae. Analysis of the phosphorylation change after reperfusion shows a trending, but nonsignificant, increase in phosphorylation of TnT (P = 0.08) and MLC-2 (P = 0.22). Statistical analysis of all trabeculae indicated no significant alterations in phosphorylation state of TnI, TnT, MyBP-C, or MLC-2 upon treatment and OH˙ production.

Fig. 6.

Myofilament fraction protein phosphorylation was determined by comparing the protein band density of the Sypro Ruby protein gel stain (total protein) on the same gel stained with Pro-Q diamond (phosphor-protein). Molecular weight (MW) markers include lane 1 BioRad dual stain ladder and lane 2 peppermint stick (Molecular Probes) phosphor-protein marker positive control. None of the indicated bands was significantly different between control and OH˙-exposed muscles (n = 5 per group). A: densitometric measurements of phosphorylated protein compared with total actin. Values are means ± SE. B: representative blot of Sypro Ruby Gel stain (Invitrogen). C: representative blot of ProQ Diamond phospho-protien stain (Invitrogen). MyBP-C, myosin-binding protein C; TnT, troponin T; TnI, troponin I; MLC-2, myosin light chain 2; AU, arbitrary units.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that direct acute exposure of rabbit trabeculae to OH˙ is marked by an acute increase in Fdia, in parallel with the diastolic calcium and the sustained increase in Fdia at the new steady state (after 45 min). At this new steady state, there is an increase in myofilament calcium sensitivity compared with before OH˙-induced injury. These data indicate calcium overload is mainly, if not entirely, responsible for the acute myocardial dysfunction after OH˙-induced injury. The sustained dysfunction is mainly due to the alteration in myofilament responsiveness.

OH˙ induced injury in isolated rabbit myocardium.

The acute response of OH˙ radicals on rabbit myocardium is similar to what has been previously described in different species (16, 42). A transient, rigorlike contraction develops several minutes after OH˙ exposure. During the acute phase, this injury is marked by an increase in diastolic tension and a decreased Fdev. During the recovery phase, Fdia declines somewhat, but does not recover to pre-OH˙ radical levels, indicating a sustained injury. At this new baseline, Fdia remained elevated, and active Fdev remains decreased. Assessment of RT50 and RT90-RT50 indicated that myofilament relaxation kinetics were slowed after the injury, while time to peak tension was unchanged, suggesting a specific impairment of relaxation kinetics alone. This prolongation might be due to reduced Ca2+ reabsorption speed and/or capacity by the SR. The depressed contractile state was accompanied by the attenuation in the force-frequency response, one of the classic hallmarks of heart failure, after the OH˙ injury.

Previous studies also demonstrated a decrease in SR Ca2+-ATPase activity at increasing concentrations of OH˙ (10), as well as a significant attenuation of the positive force-frequency relationship after the exposure of OH˙ (22, 35, 42). A flat or negative force-frequency relationship is viewed as an indicator of impairment of SR function and is one of the classic hallmarks of congestive heart failure (33). These studies indicate that there is a direct impairment of SR function due to OH˙ exposure. From these prior studies and our new findings, we conclude that calcium overload plays a significant role in the acute cardiac dysfunction observed in OH˙-induced injury.

Calcium overload in acute OH˙-induced injury.

One of the main goals of this study is to assess the potential role of the calcium overload at different time points during the injury phase. To address the clinical problem of ischemia-reperfusion injury, effectively in future stages, it is imperative that we understand at what time point, during the injury process, alterations in calcium handling are responsible for the derangement of contractile function. The present study is the first to directly observe the temporally resolved influence of altered calcium handling activity on the contractile response of the cardiac muscle to OH˙-induced injury. To test our hypothesis, that deranged calcium handling (increased diastolic calcium levels and reduced calcium transient amplitude) plays a major role during acute/early OH˙-induced injury and impaired cardiac contractility, we measured the amplitude and kinetics of calibrated intracellular Ca2+ transients and twitch contractions simultaneously in rabbit trabeculae after OH˙ exposure. After acute OH˙-induced injury, there is a marked increase in resting tension, in parallel with an increase in diastolic calcium. We observed these parameters until the transient acute dysfunction subsided and Fdia and Fdev had reached their new steady state (45 min after OH˙ exposure). At this new baseline, diastolic calcium returned to near-normal levels (pre-OH˙ radical levels) and Fdia declined, but not completely to pre-OH˙ radical levels, indicating a sustained injury. Previous studies also indicate that administration of calcium antagonists and inhibition of reverse NCX during the early reperfusion period can prevent the cardiac dysfunction and myocardial stunning (8, 9, 25, 42). This indicates that calcium overload is mainly, if not entirely, responsible for acute diastolic dysfunction after OH˙-induced injury.

Myofilament sensitivity in acute OH˙-induced injury.

In conjunction to understanding when calcium handling is deranged, it is important to know when myofilament function is involved in the phenotype of OH˙-induced injury. Although it is clear that, during ischemia-reperfusion injury, there is an acute change in myofilament response due to the metabolic acidosis and accumulation of different metabolites, the interaction between calcium overload and myofilament responsiveness, at different time points, is not clear. In support of our hypothesis that altered myofilament responsiveness plays a major role in late/sustained myocardial dysfunction after OH˙-induced injury, we observed an alteration in myofilament calcium sensitivity before and after OH˙-induced injury. Using the recently developed potassium contraction technique to assess myofilament calcium sensitivity (40, 41), we explained the observed disproportional increase in force for a given calcium concentration in the dynamic relaxation phase, after the OH˙ compared with pre-OH˙ exposure level. Even if we exclude the elevated baseline (i.e., normalize to zero) that is likely a result of rigor cross bridges, we still observe a leftward shift of the force-calcium relationship. Thus we concluded that a sensitization of the myofilaments partially, or perhaps exclusively, accounts for the increase in Fdia during the sustained injury phase. Similar to a previous study (42), neither maximal force development nor cooperativity (Hill coefficient) was significantly different. Taken together, these results indicate that the acute injury that occurs after OH˙ exposure is, significantly, due to calcium overload in the acute phase, while the sustained myocardial dysfunction is, in part, due to increased myofilament responsiveness.

Interaction between myofilament responsiveness and deranged calcium handling.

Although it is clear that, despite the intracellular calcium overload, myofilament alterations are the prominent cause of contractile dysfunction by OH˙, the possible interactions of these two mechanisms at different time points of ischemia-reperfusion injury remain unclear. During myocardial reperfusion, ROS are generated by xanthine oxidase (mainly from endothelial cells) and NADPH oxidase (mainly from neutrophils). In addition to the dysfunction of the SR and contributing to intracellular Ca2+ overload (34), there is an abrupt increase in intracellular Ca2+ damaging the cell membrane by lipid peroxidation, inducing enzyme denaturation, and causing direct oxidative damage to DNA. During the initial phase of reperfusion injury, Na+ is extruded out of the myocyte by reverse-mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange and leads to the calcium overload (42), specifically due to depletion of ATP leading to impaired Na+-K-ATPase, in the acute phase of injury. This calcium overload is mainly responsible for the cardiac dysfunction. Increases in myofilament calcium sensitivity could lead to impaired relaxation, inducing a diastolic dysfunction. Improving the myofilament calcium sensitivity, this increases the binding probability of calcium and thus prohibits the uniform cross-bridge cycling required for relaxation. Therefore, chronic sensitization of the myofilament to calcium may generate diastolic dysfunction. In the later injury phase, when the SR is again supplied with ATP, Na+-K-ATPase will reactivate, and the SR will once again remove the calcium from the cytoplasm, returning calcium to near normal levels. Additionally, direct alterations of NCX may be responsible for diastolic calcium overload during reperfusion. Ischemia induces alterations in cellular pH, which can lead to deactivation of the NCX. Increased intercellular calcium, however, can lead to NCX activation. The rate of calcium extrusion through NCX is severalfold less than the rate of SR calcium release. The disproportionate regulation of calcium flux thus elicits diastolic calcium overload. The increase in diastolic calcium has been shown to produce a negative effect on cardiac function (13). Following reperfusion, increased diastolic calcium and a normalization of pH may enhance the effects of NCX in forward mode. The reperfusion-induced enhancement of NCX would account for the decreased diastolic calcium following injury and a potential decline in SR calcium load. Reduction of the SR calcium load, would inhibit full recovery of Fdev.

Further studies highlighting the posttranslational modifications of myofilament proteins have implicated PKC activation in reperfusion injury. Both TnI and TnT are known to be phosphorylated by PKC, with TnT containing four known PKC phosphorylation targets (36). The phosphorylation of TnI and TnT has been shown to lead to a 30% maximal force decrease in mouse cardiac myofilaments, with TnI phosphorylation specifically contributing to an increase in myofilament calcium sensitivity (6, 36). Here we have shown a mild increase in TnT phosphorylation following reperfusion, suggesting a possible role for TnT in the deranged calcium handling following ischemic injury. Recent studies have shown an increase in TnI and TnT phosphorylation after myocardial infarction in dog (39). The lack of statistically significant increases in TnT and TnI phosphorylation in this study could be due to this particular model. As in most models, there is an endogenous level of phosphorylation that is altered with time and frequency of pacing for a given system. Thus the differences in phosphorylation, although minimal, could be relevant when considering modifications of basal function. In addition, a methodological limitation is that the Pro-Q stain is not 100% phosphor-specific and also reacts with negatively charged proteins. Future experiments, possibly using whole protein mass spectroscopy, may be used to further investigate a role of protein phosphorylation or other posttranslational modifications. Phospholamban-induced SERCA deactivation has also been attributed to the effects of PKC phosphorylation, which explains the delayed calcium reabsorption associated with OH˙ treatment (30). As shown by Avner et al. (1) in skinned muscle preparations, calcium sensitivity increases on treatment with 0.5 mM H2O2. Previous studies have shown that H2O2-activated protein kinases lead to alterations in the phosphorylation of sarcomeric proteins. Additionally, studies have shown that H2O2 treatment causes the oxidation of sulfhydryl groups, affecting actin and tropomyosin (1). Thus other posttranslational modifications (such as oxidation) may have occurred that contribute to the elevated myofilament responsiveness, and these could be targets of future studies. In addition, although the immediate effects of myofilament phosphorylation are minimal, the long-term effects remain unknown.

The possibility that this increased myofilament responsiveness is due to the direct effect of OH˙ can be ruled out by the half life of OH˙: the half-life of OH˙ is too short, and changes in myofilament responsiveness only developed in the later part of the injury. Further studies are needed to show what impact the alterations of myofilament proteins have on the contractile behavior over an extended period of time, and how these myofilament alterations are potentially species dependent. By tracking intracellular calcium while monitoring contractile function, we show that acute injury that occurs after OH˙ exposure is mainly, if not entirely, due to calcium overload in the acute phase, and altered/increased myofilament responsiveness is mainly responsible for the sustained/later phase of the OH˙-induced injury. Further unraveling the temporal resolution of these distinctly different mechanisms that depress contractile function may help target novel treatment strategies for oxidative stress injury in the heart.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL-738616 (to P. M. L. Janssen) and Fellowship F31HL096397 (to K. M. Haizlip), established investigator award of the American Heart Association 0740040N (to P. M. L. Janssen), and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship Grant 0715127B (to N. Hiranandani).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.M.H., N.H., and P.M.J. conception and design of research; K.M.H., N.H., and B.J.B. performed experiments; K.M.H., N.H., B.J.B., and P.M.J. analyzed data; K.M.H., N.H., B.J.B., and P.M.J. interpreted results of experiments; K.M.H. and N.H. prepared figures; K.M.H., N.H., and P.M.J. edited and revised manuscript; K.M.H., N.H., B.J.B., and P.M.J. approved final version of manuscript; N.H. and P.M.J. drafted manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Avner BS, Hinken AC, Yuan C, Solaro RJ. H2O2 alters rat cardiac sarcomere function and protein phosphorylation through redox signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H723–H730, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Backx PH, Ter Keurs HE. Fluorescent properties of rat cardiac trabeculae microinjected with fura-2 salt. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H1098–H1110, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biesiadecki BJ, Tachampa K, Yuan C, Jin JP, de Tombe PP, Solaro RJ. Removal of the cardiac troponin I N-terminal extension improves cardiac function in aged mice. J Biol Chem 285: 19688–19698, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bolli R, Marban E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial stunning. Physiol Rev 79: 609–634, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bupha-Intr T, Haizlip KM, Janssen PM. Temporal changes in expression of connexin 43 after load-induced hypertrophy in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H806–H814, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buscemi N, Foster DB, Neverova I, Van Eyk JE. p21-activated kinase increases the calcium sensitivity of rat triton-skinned cardiac muscle fiber bundles via a mechanism potentially involving novel phosphorylation of troponin I. Circ Res 91: 509–516, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Tombe PP, ter Keurs HE. Force and velocity of sarcomere shortening in trabeculae from rat heart. Effects of temperature. Circ Res 66: 1239–1254, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ehring T, Bohm M, Heusch G. The calcium antagonist nisoldipine improves the functional recovery of reperfused myocardium only when given before ischemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 20: 63–74, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrari R, Curello S, Ceconi C, Cargnoni A, Pasini E, Visioli O. Cardioprotection by nisoldipine: role of timing of administration. Eur Heart J 14: 1258–1272, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flesch M, Maack C, Cremers B, Baumer AT, Sudkamp M, Bohm M. Effect of beta-blockers on free radical-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction. Circulation 100: 346–353, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao WD, Liu Y, Marban E. Selective effects of oxygen free radicals on excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular muscle. Implications for the mechanism of stunned myocardium. Circulation 94: 2597–2604, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haizlip KM, Bupha-Intr T, Biesiadecki BJ, Janssen PM. Effects of increased preload on the force frequency response and contractile kinetics in early stages of cardiac muscle hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2509–H2517, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hasenfuss G, Reinecke H, Studer R, Pieske B, Meyer M, Drexler H, Just H. Calcium cycling proteins and force-frequency relationship in heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol 91: 17–22, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heusch G, Haigney MC, Lakatta EG, Stern MD, Silverman HS. Myocardial stunning: a role for calcium antagonists during ischaemia? Cardiovasc Res 26: 14–19, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hiranandani N, Billman GE, Janssen PM. Effects of hydroxyl radical induced-injury in atrial versus ventricular myocardium of dog and rabbit. Front Physiol 1: 25, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hiranandani N, Bupha-Intr T, Janssen PML. SERCA overexpression reduces hydroxyl radical injury in murine myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H3130–H3135, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hiranandani N, Varian KD, Monasky MM, Janssen PML. Frequency-dependent contractile response of isolated cardiac trabeculae under hypo-, normo-, and hyperthermic conditions. J Appl Physiol 100: 1727–1732, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Janssen PML, de Tombe PP. Uncontrolled sarcomere shortening increases intracellular Ca2+ transient in rat cardiac trabeculae. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H1892–H1897, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janssen PML, Hunter WC. Force, not sarcomere length, correlates with prolongation of isosarcometric contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H676–H685, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Janssen PML, Lehnart SE, Prestle J, Hasenfuss G. Preservation of contractile characteristics of human myocardium in multi-day cell culture. J Mol Cell Cardiol 31: 1419–1427, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janssen PML, Stull LB, Marban E. Myofilament properties comprise the rate-limiting step for cardiac relaxation at body temperature in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H499–H507, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Janssen PML, Zeitz O, Hasenfuss G. Transient and sustained impacts of hydroxyl radicals on sarcoplasmic reticulum function: protective effects of nebivolol. Eur J Pharmacol 366: 223–232, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Josephson RA, Silverman HS, Lakatta EG, Stern MD, Zweier JL. Study of the mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl free radical-induced cellular injury and calcium overload in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 266: 2354–2361, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Layland J, Kentish JC. Positive force- and [Ca2+]i-frequency relationships in rat ventricular trabeculae at physiological frequencies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H9–H18, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Massoudy P, Becker BF, Seligmann C, Gerlach E. Preischaemic as well as postischaemic application of a calcium antagonist affords cardioprotection in the isolated guinea pig heart. Cardiovasc Res 29: 577–582, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monasky MM, Biesiadecki BJ, Janssen PM. Increased phosphorylation of tropomyosin, troponin I, and myosin light chain-2 after stretch in rabbit ventricular myocardium under physiological conditions. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 1023–1028, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Monasky MM, Varian KD, Davis JP, Janssen PML. Dissociation of force decline from calcium decline by preload in isolated rabbit myocardium. Pflügers Arch 456: 267–276, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mulieri LA, Hasenfuss G, Ittleman F, Blanchard EM, Alpert NR. Protection of human left ventricular myocardium from cutting injury with 2,3-butanedione monoxime. Circ Res 65: 1441–1449, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mulieri LA, Hasenfuss G, Leavitt B, Allen PD, Alpert NR. Altered myocardial force-frequency relation in human heart failure. Circulation 85: 1743–1750, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noland TA, Jr, Kuo JF. Protein kinase C phosphorylation of cardiac troponin T decreases Ca(2+)-dependent actomyosin MgATPase activity and troponin T binding to tropomyosin-F-actin complex. Biochem J 288: 123–129, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raman S, Kelley MA, Janssen PML. Effect of muscle dimensions on trabecular contractile performance under physiological conditions. Pflügers Arch 451: 625–630, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodriguez EK, Hunter WC, Royce MJ, Leppo MK, Douglas AS, Weisman HF. A method to reconstruct myocardial sarcomere lengths and orientations at transmural sites in beating canine hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 263: H293–H306, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rossman EI, Petre RE, Chaudhary KW, Piacentino V, 3rd, Janssen PM, Gaughan JP, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Abnormal frequency-dependent responses represent the pathophysiologic signature of contractile failure in human myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 36: 33–42, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saini-Chohan HK, Dhalla NS. Attenuation of ischemia-reperfusion-induced alterations in intracellular Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes from hearts treated with N-acetylcysteine and N-mercaptopropionylglycine. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 87: 1110–1119, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schouten VJ, ter Keurs HE. The force-frequency relationship in rat myocardium. The influence of muscle dimensions. Pflügers Arch 407: 14–17, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sumandea MP, Pyle WG, Kobayashi T, de Tombe PP, Solaro RJ. Identification of a functionally critical protein kinase C phosphorylation residue of cardiac troponin T. J Biol Chem 278: 35135–35144, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Talukder MA, Kalyanasundaram A, Zhao X, Zuo L, Bhupathy P, Babu GJ, Cardounel AJ, Periasamy M, Zweier JL. Expression of SERCA isoform with faster Ca2+ transport properties improves postischemic cardiac function and Ca2+ handling and decreases myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2418–H2428, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. ter Keurs HE, Rijnsburger WH, van Heuningen R, Nagelsmit MJ. Tension development and sarcomere length in rat cardiac trabeculae. Evidence of length-dependent activation. Circ Res 46: 703–714, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Eyk JE, Colantonio DA, Przyklenk K. Degradation of troponin I is not essential for myocardial stunning (Abstract). Circulation 104: II-314, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Varian KD, Kijtawornrat A, Gupta SC, Torres CA, Monasky MM, Hiranandani N, Delfin DA, Rafael-Fortney JA, Periasamy M, Hamlin RL, Janssen PML. Impairment of diastolic function by lack of frequency-dependent myofilament desensitization rabbit right ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Heart Fail 2: 472–481, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Varian KD, Raman S, Janssen PML. Measurement of myofilament calcium sensitivity at physiological temperature in intact cardiac trabeculae. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2092–H2097, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zeitz O, Maass AE, Van Nguyen P, Hensmann G, Kogler H, Moller K, Hasenfuss G, Janssen PML. Hydroxyl radical-induced acute diastolic dysfunction is due to calcium overload via reverse-mode Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchange. Circ Res 90: 988–995, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P, Williams R, Rayburn BK, Smith D, Weisfeldt ML, Flaherty JT. Measurement and characterization of postischemic free radical generation in the isolated perfused heart. J Biol Chem 264: 18890–18895, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]