Abstract

Exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress (MS) and cold pressor test (CPT) has been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Recent epidemiological studies identify sleep deprivation as an important risk factor for hypertension, yet the relations between sleep deprivation and cardiovascular reactivity remain equivocal. We hypothesized that 24-h total sleep deprivation (TSD) would augment cardiovascular reactivity to MS and CPT and blunt the MS-induced forearm vasodilation. Because the associations between TSD and hypertension appear to be stronger in women, a secondary aim was to probe for sex differences. Mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), and muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) were recorded during MS and CPT in 28 young, healthy subjects (14 men and 14 women) after normal sleep (NS) and 24-h TSD (randomized, crossover design). Forearm vascular conductance (FVC) was recorded during MS. MAP, FVC, and MSNA (n = 10) responses to MS were not different between NS and TSD (condition × time, P > 0.05). Likewise, MAP and MSNA (n = 6) responses to CPT were not different between NS and TSD (condition × time, P > 0.05). In contrast, increases in HR during both MS and CPT were augmented after TSD (condition × time, P ≤ 0.05), and these augmented HR responses persisted during both recoveries. When analyzed for sex differences, cardiovascular reactivity to MS and CPT was not different between sexes (condition × time × sex, P > 0.05). We conclude that TSD does not significantly alter MAP, MSNA, or forearm vascular responses to MS and CPT. The augmented tachycardia responses during and after both acute stressors provide new insight regarding the emerging links among sleep deprivation, stress, and cardiovascular risk.

Keywords: autonomic activity, blood pressure, cold pressor test, mental stress, tachycardia

the extent of cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress (MS) and cold pressor test (CPT) in young men and women has been shown to have some predictive value regarding the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Specifically, exaggerated blood pressure reactivity to acute MS or CPT has been repeatedly linked to an increased incidence of hypertension (25, 28, 29, 47, 52). Additionally, studies report that prehypertensive individuals demonstrate an augmented pressor response to acute MS (22, 27, 36, 40), and studies have reported that the magnitude of MS cardiovascular reactivity is associated with resting blood pressure levels years later (28, 29).

In addition to blood pressure reactivity, forearm vascular responses to MS may be an important predictor of cardiovascular risk. Previous work has demonstrated an augmented blood pressure response to acute MS in prehypertensive adults (27, 36, 40), and it has been suggested that this augmentation is due, in part, to a blunted forearm vasodilatory response (36, 40). Similarly, Cardillo et al. (8) have reported that increases in forearm blood flow (FBF) during MS are attenuated in hypertensive adults. Thus evidence is accumulating to suggest that both exaggerated pressor responses and/or blunted forearm vasodilatory responses to acute stress may be important risk factors for hypertension.

Recent epidemiological studies estimate that more than one-third of adults in the United States obtain inadequate sleep (12a, 19). Moreover, studies report an association between inadequate sleep and hypertension (7, 18, 19). The influence of sleep deprivation on cardiovascular reactivity to MS and CPT remains controversial (17, 24). Kato et al. (24) reported that total sleep deprivation (TSD) did not alter cardiovascular reactivity to MS or CPT, whereas a more recent study by Franzen et al. (17) documents an augmented blood pressure reactivity to MS after TSD. Thus it remains unclear if TSD alters cardiovascular reactivity to MS or CPT; moreover, neither study (17, 24) examined the influence of TSD on forearm vascular reactivity to MS. Studies report that sleep deprivation can elicit vascular dysfunction in young, healthy subjects (2, 37, 45). Therefore, the primary purpose of the present study was to examine the influence of 24-h TSD on cardiovascular reactivity to acute MS and CPT. We hypothesized that TSD would augment cardiovascular reactivity to MS and CPT and blunt the forearm vasodilatory response to MS. Additionally, a recent epidemiological study reported that short sleep duration and hypertension are significantly correlated in women but not men (7). Therefore, a secondary purpose of this study was to probe for potential sex differences.

METHODS

Subjects.

This study examined 28 healthy adults—14 men (age 22 ± 1 yr, height 176 ± 2 cm, weight 79 ± 4 kg, body mass index 25 ± 1 kg/m2) and 14 women (22 ± 1 yr, height 165 ± 2 cm, weight 63 ± 4 kg, body mass index 23 ± 1 kg/m2). Resting baseline data for these participants have been reported previously (9). Exclusion criteria included history of autonomic dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes; all were nonsmokers. All participants demonstrated an apnea-hypopnea index <10 events/h, according to an at-home ApneaLink evaluation (ResMed, San Diego, CA) interpreted by a board-certified sleep physician (J. P. DellaValla). All subjects abstained from exercise, alcohol, and caffeine for at least 12 h prior to laboratory testing. All female subjects had regular menstrual cycles (range 26–30 days) and were tested during the early follicular phase (i.e., days 2–5) of their cycle. Female participants were not taking oral contraceptives or other hormonal supplementations. All subjects received an orientation session, and each participant provided his or her written, informed consent. The experimental protocol and procedures were approved by the Michigan Technological University Institutional Review Board.

Experimental design.

Participants were tested ∼1 mo apart to ensure that all females were in the early follicular phase on both testing days. Participants reported to the laboratory for testing at 7:30 AM in the morning after either normal sleep (NS) or 24-h TSD. The order of the trials (i.e., TSD vs. NS) was randomized. Details of the TSD protocol are described previously (9). Wrist actigraphy (Actiwatch-64; Mini Mitter, Philips Respironics, Bend, OR) was used to obtain the average sleep times for at least three consecutive nights preceding each trial. In <10% of nights, actigraphy data were not available; thus self-reported sleep diary data were used. A board-certified sleep physician (J. P. DellaValla) analyzed all actigraphy and sleep diary data. Participants were getting adequate sleep before the NS (7.3 ± 0.2 h in men and 7.2 ± 0.2 h in women) and TSD (7.6 ± 0.3 h in men and 7.4 ± 0.3 h in women) trials for the three nights preceding each testing day.

On each testing day (NS and TSD), three resting-seated blood pressures were taken at 7:30 AM after at least 5 min of quiet rest. Following the blood pressure recordings, state anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory questionnaire for adults (41), followed by fasting venipuncture to determine levels of estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone. Following these initial measurements, participants were situated in the supine position on a laboratory table for cardiovascular and neural instrumentation. Following a 10-min baseline reported previously (9), there was a 10-min nonrecorded period in which forearm venous occlusion plethysmography (VOP) was instrumented. Following the VOP instrumentation, all subjects participated in a MS trial that consisted of a 5-min supine baseline, 5 min of MS (arithmetic), and 5 min of recovery. The mental arithmetic involved subtracting a single digit number (e.g., six or seven) continuously from random two- to three-digit numbers while investigators verbally pressured the subject to subtract faster. Immediately following the MS protocol, subjects reported their perceived stress during the mental arithmetic using a standard scale of zero to four (6). Following a 10-min nonrecorded recovery, which allowed for removal of the VOP equipment, subjects performed a CPT trial, which consisted of a 3-min baseline, 2 min of CPT (hand submersed in ice water, ∼1°C), and a 3-min recovery.

Measurements.

Beat-to-beat arterial blood pressure was recorded continuously using a Finometer (Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Three consecutive supine blood pressures were taken prior to both the MS and CPT baselines via an automated sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM-907XL, Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) to calibrate the Finometer. Arterial blood pressures were expressed as systolic (SAP), diastolic, and mean (MAP) arterial blood pressures. Heart rate (HR) was recorded continuously via a three-lead electrocardiogram, and respiratory rate was measured continuously with the use of a pneumobelt.

Multifiber recordings of muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) were obtained by inserting a tungsten microelectrode (FHC, Bowdoin, ME) into the peroneal nerve of the right leg, while a reference electrode was inserted 2–3 cm subcutaneously from the recording electrode. Both electrodes were connected to a differential preamplifier and then to an amplifier (total gain of 80,000) where the nerve signal was band-pass filtered (700–2,000 Hz) and integrated (time constant = 0.1). Quality recordings of MSNA were considered to be spontaneous, pulse-synchronous bursts that increased during end-expiratory apnea and remain unchanged during auditory stimulus or stroking of the skin.

FBF was measured during the MS protocol via VOP (EC6; D. E. Hokanson, Bellevue, WA). Briefly, a mercury-in-silastic strain gauge was placed around each subject's forearm at the point of greatest circumference. Cuffs were placed around each subject's left wrist and upper arm. The occluding cuff placed on the wrist was inflated to 220 mmHg, whereas the upper-arm cuff was inflated to 60 mmHg for 8 s and deflated for 7 s (i.e., 15-s blood flow intervals). Forearm vascular conductance (FVC) was calculated as FBF divided by MAP.

Data analysis.

Data were imported and analyzed in the WinCPRS software program (Absolute Aliens, Turku, Finland). R-waves were detected and marked in the time series. Bursts of MSNA were automatically detected on the basis of amplitude with the use of a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1, within a 0.5-s search window centered on a 1.3-s expected burst peak latency from the previous R-wave. Potential bursts were displayed and edited by one trained investigator. MSNA was expressed as burst frequency (bursts/min), burst incidence (bursts/100 heartbeats), and total MSNA (i.e., the sum of the normalized burst areas/min). Due to the complexity of the experimental approach (see discussion for more detail), successful and complete recordings of MSNA throughout the MS and CPT trials were limited to n = 10 and n = 6, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

All data were analyzed statistically using commercial software (SPSS 20.0, IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY). We used repeated-measures ANOVA with time (baseline, intervention, and recovery) and condition (NS vs. TSD) as within-subjects factors and sex (men vs. women) as a between-subjects factor. Post hoc analysis was performed when significant condition × time interactions were detected. Pearson correlations were used to examine the relations between changes of HR and percent changes of FVC during MS. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Means were considered significantly different at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline hemodynamics.

Our previous study reported that TSD elicited increases of resting-seated and supine baseline blood pressure (9). Consistent with this, the present study reveals that TSD increased baseline SAP immediately preceding the MS and CPT trials (P < 0.05). TSD did not alter resting HR, FBF, and FVC during the baselines preceding MS or CPT (condition × sex, P > 0.05).

Cardiovascular and neural reactivity to MS and CPT.

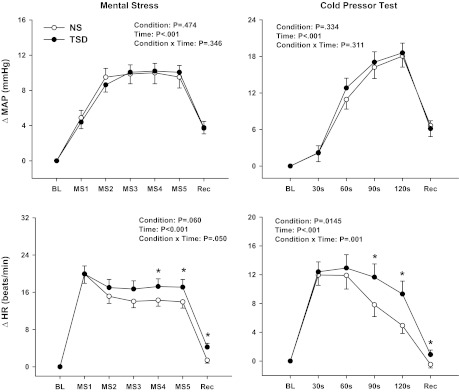

Figure 1 depicts that MS and CPT elicited robust increases in both MAP and HR (time, P < 0.01). Whereas the increases in MAP during MS and CPT were similar between NS and TSD (condition × time, P = 0.35 and P = 0.31, respectively), TSD elicited an augmented HR reactivity (MS: condition × time, P = 0.05; CPT: P < 0.01). Likewise, HR responses remained elevated during both stress recovery periods following TSD compared with NS (condition × time, P < 0.01). MSNA reactivity to MS [change in (Δ)2 ± 1 vs. Δ0 ± 1 bursts/min; condition × time, P = 0.40; n = 10] and CPT (Δ14 ± 4 vs. Δ14 ± 6 bursts/min; condition × time, P = 0.48; n = 6) was similar between NS and TSD. MSNA reactivity to MS and CPT was also similar between NS and TSD when expressed as burst incidence and total MSNA (data not reported).

Fig. 1.

Changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) and heart rate (ΔHR) to mental stress (MS; n = 28) and cold pressor test (CPT; n = 26) after a normal night of sleep (NS) and 24-h total sleep deprivation (TSD). MAP and HR increased significantly during MS and CPT. TSD did not alter the MAP reactivity but elicited an exaggerated HR response to MS and CPT. *P < 0.05 vs. corresponding NS. BL, baseline; Rec, recovery; MS1-5, mental stress in minutes 1–5.

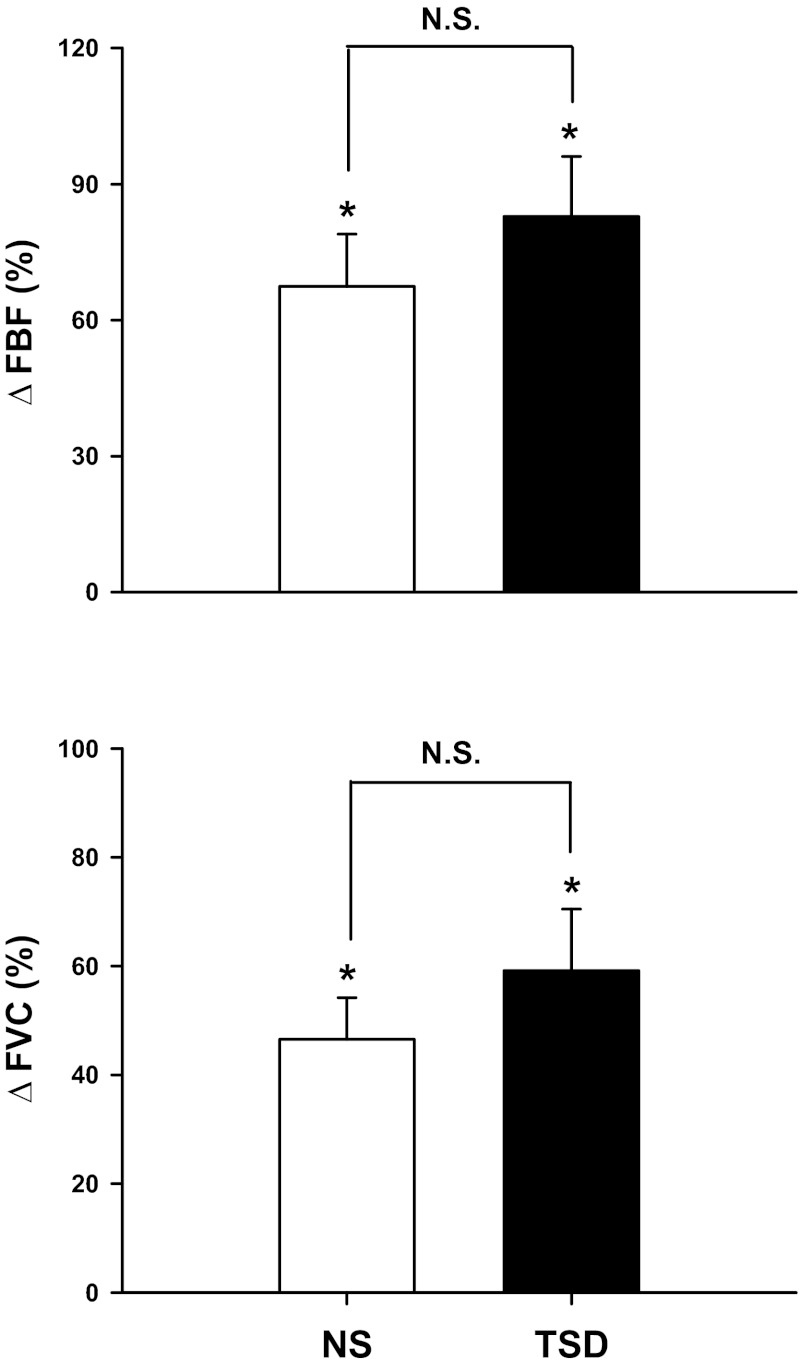

Figure 2 demonstrates that FBF and FVC increased significantly during 5-min MS (time, P < 0.01), and these responses were not different between NS and TSD. Specifically, TSD did not alter ΔFBF (Δ67 ± 12 vs. Δ83 ± 13%; condition × time, P = 0.30) or ΔFVC (Δ47 ± 8 vs. Δ59 ± 11%; condition × time, P = 0.25). Changes in HR were significantly correlated to changes in FVC during MS after NS (r = 0.59, P < 0.01) and TSD (r = 0.61, P < 0.01). Importantly, perceived stress was not different during the two trials (2.3 ± 0.2 vs. 2.5 ± 0.1 arbitrary units, P = 0.316).

Fig. 2.

Changes in forearm blood flow (ΔFBF) and forearm vascular conductance (ΔFVC) to MS (n = 25) after NS and 24 h of TSD. MS significantly elicited increases of FBF and FVC. TSD did not alter these responses. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline. N.S., not significant.

Sex comparisons.

There were no sex differences in the MAP or HR reactivities to MS (condition × time × sex, P > 0.05) or CPT (condition × time × sex, P > 0.05) following either sleep condition. Similarly, changes in FBF (condition × time × sex, P = 0.95) and FVC (condition × time × sex, P = 0.76) during MS were also not different between sexes.

DISCUSSION

The current study investigated the influence of 24-h TSD on cardiovascular reactivity to MS and CPT. We report three new findings. First, TSD did not alter the MAP reactivity to MS or CPT; however, TSD elicited an augmented HR reactivity during both MS and CPT. Moreover, this elevated HR response during TSD persisted throughout the recovery periods of both stressors. Second, contrary to our original hypothesis, increases in FBF and FVC during MS were not blunted by TSD. Third, no sex differences were observed among the MAP, HR, or forearm vascular reactivity after TSD. Our findings suggest that sleep deprivation elicits heightened HR reactivity and delayed HR recovery to MS and CPT; these findings may help to explain the emerging links among sleep deprivation, stress, and cardiovascular disease.

Large-scale longitudinal studies have documented that augmented cardiovascular reactivity to acute stressors such as MS and CPT is linked to an increased risk of developing hypertension (13, 26, 28, 43, 46, 52). Moreover, smaller observation studies report that both prehypertensive adults (22, 27, 36, 40) and subjects with a family history of hypertension (30, 51) demonstrated augmented blood pressure responses to MS. Thus evidence is accumulating to suggest that exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity to stress is linked to an increased incidence of future hypertension.

Recent epidemiological studies demonstrate a consistent link between sleep deprivation and hypertension in humans (7, 18, 19). However, the influence of TSD on cardiovascular reactivity to acute stressors remains controversial (17, 24). Kato et al. (24) reported that cardiovascular reactivity to acute stress was not different between NS and TSD. However, it is important to note that the MS protocol used in the study (24) failed to elicit significant increases in HR or blood pressure during MS in the control (i.e., NS) condition, thus limiting interpretation. Our laboratory (10–12) and others (3, 6, 20, 33, 49) consistently report robust increases in both HR and blood pressure during MS. In contrast to the findings of Kato et al. (24), a more recent study by Franzen et al. (17) reported an augmented SAP response to MS after TSD. Thus the influence of TSD on cardiovascular reactivity remains unresolved.

In the present study, we report that HR reactivity to both MS and CPT was exaggerated significantly after TSD, whereas blood pressure reactivities to both stressors were similar between NS and TSD. Light et al. (26) reported that individuals with high HR reactivity to acute stress were more likely to develop hypertension and tachycardia at a 10- to 15-yr follow-up compared with low HR reactors. Similarly, Stewart and France (43) demonstrated an association between heightened HR reactivity to MS and elevated SAP in a 3-yr follow-up investigation. Thus the augmented HR reactivities to MS and CPT after TSD may have important clinical relevance.

Wallin et al. (48) have shown a positive correlation between MSNA and cardiac norepinephrine spillover in healthy subjects. Because MSNA responses to MS and CPT were similar between NS and TSD, it is tempting to speculate that the heightened cardiac sympathetic activation is unlikely to be a primary contributor to the HR reactivity after TSD. However, there are several reasons why we are not comfortable with this speculation. First, whereas MSNA and cardiac norepinephrine spillover are correlated, Wallin et al. (48) report that these correlations are stronger at rest compared with sympathoexcitatory maneuvers. Moreover, the authors suggest that the balance between sympathetic outflows to heart and skeletal muscle differs between maneuvers (i.e., handgrip exercise vs. MS). Second, recent studies suggest differentiation of sympathetic outflow to the heart and skeletal muscle in certain cardiovascular disease states (15, 32). Likewise, Rundqvist et al. (35) demonstrated that early, mild heart failure is associated with augmented cardiac sympathetic activity but not sympathetic outflow to the skeletal muscle vasculature. Although our subjects were young and healthy, the TSD trial did elicit an acute hypertensive response. Collectively, it would appear that an investigation examining the effects of sleep deprivation on cardiac norepinephrine spillover might be warranted to better understand the heightened HR reactivity reported in the present study. Increases in cardiac sympathetic outflow are important to human hypertension (14, 16).

For decades, cardiovascular reactivity has been examined in the laboratory with few attempts to generalize reactivity assessed in the laboratory to the “real world” (39). This remains a limitation of the cardiovascular reactivity theory. However, it appears that the use of data “aggregation” across multiple stressors can improve generalizability (39). Additionally, evidence is accumulating to suggest that cardiovascular recovery from stress may be useful in predicting long-term cardiovascular health (21, 26, 38, 42–44). Specifically, Heponiemi et al. (21) reported that faster HR recovery after the MS was related to lower levels of carotid atherosclerosis. Additionally, Stewart et al. (44) demonstrated that faster HR recovery from five psychological tasks was related to a lower risk of developing hypertension at a 3-yr follow-up. In the present study, we found that TSD elicited a delayed HR recovery response after both MS and CPT. When combined with the augmented HR reactivity during both acute stressors, these findings may provide valuable insight into the emerging links among sleep deprivation, stress, and cardiovascular disease. The aggregation across stressors (i.e., MS and CPT) and trial time (i.e., actual stressor and recovery) lends credibility to the idea that TSD elicits heightened HR reactivity to acute stress.

MS elicits a consistent and reproducible forearm vasodilatory response (4, 5, 10). There is growing evidence to suggest that blunted forearm vasodilation is a potential mechanism for the augmented pressor response to MS in at-risk populations (8, 34, 36). Weil et al. (50) reported recently that inadequate sleep elicits an excess forearm vasoconstrictor tone, which the authors suggest contributes to an increased risk of hypertension and other forms of cardiovascular disease. Additionally, studies have demonstrated vascular dysfunction in both large-conductance artery (i.e., brachial artery) (2, 45) and cutaneous microvascular beds (37) after chronic and/or acute sleep deprivation. FVC measurements via VOP adequately reflect vasodilation and/or vasoconstriction in the limb vasculature (31). Contrary to our initial hypothesis, our FVC data indicate that MS elicits similar forearm vasodilatory responses after NS and TSD. In fact, our data demonstrate a trend toward heightened forearm vasodilation after TSD. Pike et al. (33) reported a striking correlation between HR and FVC responses to MS and suggested that mechanical stimulation associated with higher HR reactivity is a key contributor to increases of FVC during MS. We observed similar correlations between FVC and HR as that reported by Pike et al. (33), and these relations between FVC and HR were present after both NS and TSD. That said, TSD did not statistically alter FVC responses to MS. This finding is consistent with the idea that changes in forearm vascular tone are not induced by 24-h TSD but instead require “habitual short sleep duration” (50).

A recent epidemiological study reports that the associations between short sleep duration and the risk of hypertension are stronger in women compared with men (7). Therefore, a secondary aim of this study was to probe for sex differences in cardiovascular reactivity after TSD. Our data indicate that there are no sex differences in blood pressure or HR reactivities to MS and CPT following TSD. Furthermore, there were no sex differences in the FVC response to MS. Thus the stronger associations between short sleep duration and the risk of hypertension do not appear to be related to different cardiovascular reactivity to acute stressors in men and women.

We recognize three important study limitations. First, our experimental approach used a 24-h TSD protocol. Whereas this remains a primary experimental intervention for examining physiological responses to inadequate sleep, it is recognized that accumulated sleep debt via multiple days of short sleep duration is much more common in a nonlaboratory setting (i.e., daily living). Thus we caution the translation of our findings beyond the context of 24-h TSD. Given the augmented HR reactivity to both MS and CPT reported in the present study, we believe that future work using the more complex and time-intensive sleep-restriction model (i.e., sleep time <6 h/night over consecutive days) appears warranted. Second, our recent study examining resting baseline responsiveness to TSD with the present cohort of subjects reported MSNA in 10 men and 10 women (9). Unfortunately, the microneurography electrode was dislodged during several of the MS and/or CPT trials in our subjects, thus limiting our MSNA sample sizes. Given the randomized, crossover approach (i.e., NS vs. TSD), we were not comfortable “repositioning” the electrode and rerunning baselines and interventions; we believed that providing a similar laboratory environment and experimental sequence was essential for the cardiovascular reactivity comparisons. Whereas the MSNA data were critical for our resting baseline study (9), it was not viewed as essential for the MS and CPT trials, because our primary hypotheses focused on the cardiovascular reactivity. In the present study, we were able to statistically analyze the MSNA data with regard to our primary hypothesis (i.e., TSD vs. NS) but were unable to probe our secondary hypothesis (i.e., sex difference). Third, TSD has been shown to influence the renal system (i.e., excess natriuresis and osmotic diuresis), which could affect hemodynamic changes (23). We did not monitor hydration status or renal hormone levels. Future work in this area might include measurements of renal hormones, catecholamines, and hydration status.

In summary, 24-h TSD does not affect the blood pressure reactivity to MS or CPT nor does it influence FVC reactivity to MS. In contrast, TSD elicits an augmented HR reactivity and delayed recovery during both MS and CPT. This exaggerated HR reactivity after TSD is of clinical relevance (21, 26, 43, 44) and provides new and valuable insight regarding the complex and poorly understood relations among sleep deprivation, stress, and cardiovascular disease.

GRANTS

Support for this project was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-098676).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.P.D. and J.R.C. conception and design of research; H.Y., J.J.D., R.A.L., and J.R.C. performed experiments; H.Y., J.J.D., R.A.L., and J.P.D. analyzed data; H.Y., J.J.D., R.A.L., J.P.D., and J.R.C. interpreted results of experiments; H.Y. prepared figures; H.Y., J.J.D., R.A.L., and J.R.C. drafted manuscript; H.Y., J.J.D., R.A.L., J.P.D., and J.R.C. edited and revised manuscript; H.Y., J.J.D., R.A.L., J.P.D., and J.R.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Thomas Drummer, Christopher Schwartz, Michelle King, and Kristen Reed for their technical assistance. We also thank all of our subjects for their participation.

REFERENCES

- 2. Amir O, Alroy S, Schliamser JE, Asmir I, Shiran A, Flugelman MY, Halon DA, Lewis BS. Brachial artery endothelial function in residents and fellows working night shifts. Am J Cardiol 93: 947–949, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson EA, Wallin BG, Mark AL. Dissociation of sympathetic nerve activity in arm and leg muscle during mental stress. Hypertension 9: III114–III119, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barcroft H, Brod J, Hejl BZ, Hirsjarvi EA, Kitchin AH. The mechanism of the vasodilatation in the forearm muscle during stress (mental arithmetic). Clin Sci 19: 577–586, 1960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blair DA, Glover WE, Greenfield AD, Roddie IC. Excitation of cholinergic vasodilator nerves to human skeletal muscles during emotional stress. J Physiol 148: 633–647, 1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callister R, Suwarno NO, Seals DR. Sympathetic activity is influenced by task difficulty and stress perception during mental challenge in humans. J Physiol 454: 373–387, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, Miller MA, Taggart FM, Kumari M, Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Brunner EJ, Marmot MG. Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension: the Whitehall II Study. Hypertension 50: 693–700, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO, 3rd, Panza JA. Impairment of the nitric oxide-mediated vasodilator response to mental stress in hypertensive but not in hypercholesterolemic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 1207–1213, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carter JR, Durocher JJ, Larson RA, Dellavalla JP, Yang H. Sympathetic neural responses to 24-hour sleep deprivation in humans: sex differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1991–H1997, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter JR, Kupiers NT, Ray CA. Neurovascular responses to mental stress. J Physiol 564: 321–327, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carter JR, Lawrence JE. Effects of the menstrual cycle on sympathetic neural responses to mental stress in humans. J Physiol 585: 635–641, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carter JR, Ray CA. Sympathetic neural responses to mental stress: responders, nonresponders and sex differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H847–H853, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Effect of short sleep duration on daily activities—United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60: 239–242, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chida Y, Steptoe A. Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: a meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension 55: 1026–1032, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esler M. The sympathetic system and hypertension. Am J Hypertens 13: 99S–105S, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esler M, Eikelis N, Schlaich M, Lambert G, Alvarenga M, Dawood T, Kaye D, Barton D, Pier C, Guo L, Brenchley C, Jennings G, Lambert E. Chronic mental stress is a cause of essential hypertension: presence of biological markers of stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35: 498–502, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Esler M, Ferrier C, Lambert G, Eisenhofer G, Cox H, Jennings G. Biochemical evidence of sympathetic hyperactivity in human hypertension. Hypertension 17: III29–III35, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Franzen PL, Gianaros PJ, Marsland AL, Hall MH, Siegle GJ, Dahl RE, Buysse DJ. Cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress following sleep deprivation. Psychosom Med 73: 679–682, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, Rundle AG, Zammit GK, Malaspina D. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension 47: 833–839, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gottlieb DJ, Redline S, Nieto FJ, Baldwin CM, Newman AB, Resnick HE, Punjabi NM. Association of usual sleep duration with hypertension: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep 29: 1009–1014, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halliwill JR, Lawler LA, Eickhoff TJ, Dietz NM, Nauss LA, Joyner MJ. Forearm sympathetic withdrawal and vasodilatation during mental stress in humans. J Physiol 504: 211–220, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heponiemi T, Elovainio M, Pulkki L, Puttonen S, Raitakari O, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Cardiac autonomic reactivity and recovery in predicting carotid atherosclerosis: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Health Psychol 26: 13–21, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jern S, Bergbrant A, Hedner T, Hansson L. Enhanced pressor responses to experimental and daily-life stress in borderline hypertension. J Hypertens 13: 69–79, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kamperis K, Hagstroem S, Radvanska E, Rittig S, Djurhuus JC. Excess diuresis and natriuresis during acute sleep deprivation in healthy adults. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F404–F411, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato M, Phillips BG, Sigurdsson G, Narkiewicz K, Pesek CA, Somers VK. Effects of sleep deprivation on neural circulatory control. Hypertension 35: 1173–1175, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krantz DS, Manuck SB. Acute psychophysiologic reactivity and risk of cardiovascular disease: a review and methodologic critique. Psychol Bull 96: 435–464, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Light KC, Dolan CA, Davis MR, Sherwood A. Cardiovascular responses to an active coping challenge as predictors of blood pressure patterns 10 to 15 years later. Psychosom Med 54: 217–230, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matsukawa T, Gotoh E, Uneda S, Miyajima E, Shionoiri H, Tochikubo O, Ishii M. Augmented sympathetic nerve activity in response to stressors in young borderline hypertensive men. Acta Physiol Scand 141: 157–165, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matthews KA, Katholi CR, McCreath H, Whooley MA, Williams DR, Zhu S, Markovitz JH. Blood pressure reactivity to psychological stress predicts hypertension in the CARDIA study. Circulation 110: 74–78, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matthews KA, Woodall KL, Allen MT. Cardiovascular reactivity to stress predicts future blood pressure status. Hypertension 22: 479–485, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noll G, Wenzel RR, Schneider M, Oesch V, Binggeli C, Shaw S, Weidmann P, Luscher TF. Increased activation of sympathetic nervous system and endothelin by mental stress in normotensive offspring of hypertensive parents. Circulation 93: 866–869, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O'Leary DS. Regional vascular resistance vs. conductance: which index for baroreflex responses? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H632–H637, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osborn JW, Kuroki MT. Sympathetic signatures of cardiovascular disease: a blueprint for development of targeted sympathetic ablation therapies. Hypertension 59: 545–547, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pike TL, Elvebak RL, Jegede M, Gleich SJ, Eisenach JH. Forearm vascular conductance during mental stress is related to the heart rate response. Clin Auton Res 19: 183–187, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation 99: 2192–2217, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rundqvist B, Elam M, Bergmann-Sverrisdottir Y, Eisenhofer G, Friberg P. Increased cardiac adrenergic drive precedes generalized sympathetic activation in human heart failure. Circulation 95: 169–175, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santangelo K, Falkner B, Kushner H. Forearm hemodynamics at rest and stress in borderline hypertensive adolescents. Am J Hypertens 2: 52–56, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sauvet F, Leftheriotis G, Gomez-Merino D, Langrume C, Drogou C, Van Beers P, Bourrilhon C, Florence G, Chennaoui M. Effect of acute sleep deprivation on vascular function in healthy subjects. J Appl Physiol 108: 68–75, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schuler JL, O'Brien WH. Cardiovascular recovery from stress and hypertension risk factors: a meta-analytic review. Psychophysiology 34: 649–659, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwartz AR, Gerin W, Davidson KW, Pickering TG, Brosschot JF, Thayer JF, Christenfeld N, Linden W. Toward a causal model of cardiovascular responses to stress and the development of cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med 65: 22–35, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schwartz CE, Durocher JJ, Carter JR. Neurovascular responses to mental stress in prehypertensive humans. J Appl Physiol 110: 76–82, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Steptoe A, Marmot M. Impaired cardiovascular recovery following stress predicts 3-year increases in blood pressure. J Hypertens 23: 529–536, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stewart JC, France CR. Cardiovascular recovery from stress predicts longitudinal changes in blood pressure. Biol Psychol 58: 105–120, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stewart JC, Janicki DL, Kamarck TW. Cardiovascular reactivity to and recovery from psychological challenge as predictors of 3-year change in blood pressure. Health Psychol 25: 111–118, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takase B, Akima T, Uehata A, Ohsuzu F, Kurita A. Effect of chronic stress and sleep deprivation on both flow-mediated dilation in the brachial artery and the intracellular magnesium level in humans. Clin Cardiol 27: 223–227, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Treiber FA, Davis H, Musante L, Raunikar RA, Strong WB, McCaffrey F, Meeks MC, Vandernoord R. Ethnicity, gender, family history of myocardial infarction, and hemodynamic responses to laboratory stressors in children. Health Psychol 12: 6–15, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Treiber FA, Kamarck T, Schneiderman N, Sheffield D, Kapuku G, Taylor T. Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosom Med 65: 46–62, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wallin BG, Esler M, Dorward P, Eisenhofer G, Ferrier C, Westerman R, Jennings G. Simultaneous measurements of cardiac noradrenaline spillover and sympathetic outflow to skeletal muscle in humans. J Physiol 453: 45–58, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wasmund WL, Westerholm EC, Watenpaugh DE, Wasmund SL, Smith ML. Interactive effects of mental and physical stress on cardiovascular control. J Appl Physiol 92: 1828–1834, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weil BR, Mestek ML, Westby CM, Van Guilder GP, Greiner JJ, Stauffer BL, DeSouza CA. Short sleep duration is associated with enhanced endothelin-1 vasoconstrictor tone. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 88: 777–781, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Widgren BR, Wikstrand J, Berglund G, Andersson OK. Increased response to physical and mental stress in men with hypertensive parents. Hypertension 20: 606–611, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wood DL, Sheps SG, Elveback LR, Schirger A. Cold pressor test as a predictor of hypertension. Hypertension 6: 301–306, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]