Abstract

The interplay of mechanical forces transduces diverse physico-biochemical processes to influence lung morphogenesis, growth, maturation, remodeling and repair. Because tissue stress is difficult to measure in vivo, mechano-sensitive responses are commonly inferred from global changes in lung volume, shape, or compliance and correlated with structural changes in tissue blocks sampled from postmortem-fixed lungs. Recent advances in noninvasive volumetric imaging technology, nonrigid image registration, and deformation analysis provide valuable tools for the quantitative analysis of in vivo regional anatomy and air and tissue-blood distributions and when combined with transpulmonary pressure measurements, allow characterization of regional mechanical function, e.g., displacement, strain, shear, within and among intact lobes, as well as between the lung and the components of its container—rib cage, diaphragm, and mediastinum—thereby yielding new insights into the inter-related metrics of mechanical stress-strain and growth/remodeling. Here, we review the state-of-the-art imaging applications for mapping asymmetric heterogeneous physical interactions within the thorax and how these interactions permit as well as constrain lung growth, remodeling, and compensation during development and following pneumonectomy to illustrate how advanced imaging could facilitate the understanding of physiology and pathophysiology. Functional imaging promises to facilitate the formulation of realistic computational models of lung growth that integrate mechano-sensitive events over multiple spatial and temporal scales to accurately describe in vivo physiology and pathophysiology. Improved computational models in turn could enhance our ability to predict regional as well as global responses to experimental and therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: functional imaging, high-resolution computed tomography, deformation analysis, lung development, pneumonectomy, computational model

all iteratively branching structures develop as a result of persistent physical forces acting against the resistance of one or more media. The lung continuously balances internal and external pressure gradients created by the interdependent actions of two pumps at the interface of two media: air movement generated by the respiratory muscles and blood flow generated by the entire cardiac output. The adult human lung moves ∼9,000 liters of air and ∼7,000 liters of blood daily. In addition to rhythmic stretching of alveolar septa and pulsatile flow within the bronchovasculature, lung tissue experiences cyclic mechanical strain and shear distortion caused by its weight and asymmetric deformation, as well as surface tension at air-tissue interfaces. Since mechanotransduction—the conversion of mechanical load into a cellular response—is a fundamental and universal mechanism regulating diverse physico-biochemical processes from membrane permeability, ion transport, gene transcription, enzymatic reactions, protein synthesis to cell proliferation, and differentiation [reviewed in refs. (1, 15, 49, 62, 68)], it is not surprising that the interplay of mechanical forces critically shapes fetal lung morphogenesis, postnatal growth and maturation, and compensatory growth and remodeling following the loss of functioning lung units. Here, we review 1) the clinical and experimental evidence supporting mechanical stresses as major stimuli for lung growth, 2) the evolution of imaging approaches for quantifying lung strain in relation to alveolar-capillary and bronchovasuclar growth using pneumonectomy (PNX) as an example where quantitative imaging has been applied to gain insight into mechano-sensitive adaptation, 3) the limitations and new developments in relevant imaging approaches, and 4) the continuing challenges in quantifying tissue stress and developing imaging-based computational models to interpret deformation measurements and integrate the mechanical events that occur over multiple spatial scales during growth and development.

LUNG STRESS-STRAIN DURING DEVELOPMENT AND COMPENSATORY GROWTH

Lung stress-strain during development.

Structure of the growing lung has been described in detail elsewhere (6). The newborn human lung contains only a fraction (up to 50 million) (16, 17, 48) of the alveoli in the adult lung (∼400 million) (57), with millions of “saccules”—peripheral airspaces bound by septa containing a thick, connective tissue layer between two capillary sheets. Transformation from “saccular” to “alveolar” and then “mature” morphology requires not only the addition of alveolar septa but also new capillary formation and transition from a double- to a single-capillary profile, accompanied by increased gas-exchange surface area and reduced resistance of the diffusion barrier. New alveolar subdivisions arise as secondary septae emerge from the primary alveolar walls. This process is most rapid in the first 6 mo of life and continues during the next 2-3 years (5). Some studies suggested that new alveoli continue to appear throughout somatic maturation (6). New capillary beds may arise by “intussusception” (46), a process where tissue pillars form a bridge across the lumen of an existing capillary, eventually dividing it in two.

Mechanical interactions between the thorax and lungs are crucial for normal lung maturation and function (26, 33). In fluid-filled fetal lungs, a high level of distention is normally maintained by breathing-like movements and by upper-airway resistance during apnea. Any sustained perturbation that reduces lung expansion causes fetal lung hypoplasia, leading to postnatal compromise in function. Premature birth compromises airway and alveolar formation by shortening the duration of intrauterine lung expansion (23). Abolishing rhythmic respiratory movements decreases fetal lung liquid volume, developmental gene expression, and structural growth (24, 84). Reduced lung fluid in oligohydramnios (52, 53) or inadequate space for lung expansion in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) impedes fetal lung development, whereas severe kyphoscoliosis impedes postnatal lung growth (3, 54). Conversely, increasing lung distention by fetal tracheal occlusion (31, 81) or postnatal perfluorocarbon instillation accelerates lung development (18, 20, 56, 82) via transduction of growth-related pathways. Exposure to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during maturation increases lung capacity, lung weight, protein, and DNA contents (92). These data support stress-induced acceleration of parenchyma growth and remodeling. Clinically, long-term survivors of CDH repair exhibit only a mild reduction of forced vital capacity with normal total lung capacity, airway function, and exercise performance compared with age-matched control subjects (50), suggesting that the maturing lung undergoes “catch-up” growth and compensation once mechanical stress-strain relationships between the thorax and lung are normalized.

Lung stress-strain during compensatory growth.

Mechanical thoraco-pulmonary interactions also mediate adaptation to lung disease and the reinitiation of alveolar-capillary growth in mature lungs. In a robust model of restrictive lung disease by surgical removal of lung units, e.g., unilateral PNX, the remaining units expand ∼90% to fill the thoracic cavity, whereas ventilation and perfusion/lung unit increase by a factor of one/fractional lung remaining, causing the recruitment of existing alveoli and capillaries. The resulting tissue and capillary stress transduces nearly all major homeostatic pathways (1, 2, 21, 47, 60, 72, 86, 91), leading to increased permeability and remodeling of the remaining alveolar septa and acinar airspaces and if the signal intensity exceeds a critical threshold, reinitiation of cell proliferation, protein synthesis, and matrix deposition, culminating in the generation of new gas-exchange tissue as reviewed in refs. (1, 33). The remaining conducting airways and vessels become distorted and elongated, followed by slow dilatation that partially counteracts the increase in flow resistance (11, 74). Preventing post-PNX lung expansion using a customized inflatable prosthesis significantly impairs, whereas subsequent reimposition of lung expansion upregulates, growth-related pathways and facilitates compensatory alveolar growth and function (37, 38, 87, 91). Application of CPAP in isolated lungs elicits many of the same biochemical changes seen following PNX (71). Therefore, PNX is a useful model for examining the extent and the mechanisms of mechanosensitive compensation. Conversely, the diminished mechanical interactions associated with air trapping and loss of elastic recoil in emphysema may at least partly explain the difficulty in reinducing compensatory lung growth in this condition.

QUANTIFYING REGIONAL LUNG VOLUME, STRESS AND STRAIN

Imaging regional lung volume and deformation.

The asymmetry of intrathoracic structures and rigidity of the mediastinum predispose to nonuniform distributions of mechanical stress, lobar expansion, and tissue deformation that could impact regional parenchyma structure and function. It is difficult to relate lung mechanics to structure assessed from a few selected postmortem-fixed specimens. To quantitatively relate regional as well as global anatomy to function in vivo, early studies used chest X-ray and biplane cineradiography to estimate regional volume and stress-strain relationships in canine lungs by determining the three-dimensional (3D) spatial coordinates of radio-opaque markers implanted into the parenchyma or affixed onto pleural surfaces (41, 58, 70). Mechanical deformation is measured as strain, which is usually a tensor (a geometric representation that quantifies fractional length change relative to initial length in 3D space) that can be decomposed into its stretch and shear components. Strain must be quantified relative to an initial unloaded or prestretched state; hence, the calculation of strain requires identifying unique material points within the tissue and tracking their displacement between successive images following intervention. In the studies using implanted lung markers, deformation of tetrahedrons formed by any four noncoplanar markers was expressed as strain along 3D orthogonal axes; regional mechanical properties were estimated from the tetrahedron volume changes and expressed at the centroid of each tetrahedron. These invasive studies demonstrated relatively uniform respiratory expansion of normal lobes, posture-dependent shape changes in the diaphragm and lung, displacement of the lobes relative to each other (9), differential patterns of regional ventilation and diaphragm motion during mechanical ventilation compared with spontaneous breathing, and a nonlinear relationship between regional ventilation and volume changes (40). Regional parenchyma strain exhibits volume-, posture-, and lobe-dependent variations in supine but not prone posture (70), which is partly due to mechanical interaction between the lung and diaphragm via a shift in the abdominal contents with posture. A recent computational study of human lung stress-strain also reported supine-prone differences in lung density and pleural pressure gradients that can be explained by posture-related lung-shape change in the absence of any change in gross lung shape (77). Thus components of the “container”—heart and mediastinum, rib cage, diaphragm, and abdominal content—constrain the shape and direction in which the lungs could deform. Mechanical interactions between lung and chest wall and the relative motion between lobes are significant determinants of regional ventilation, whereas heterogeneity in expansion, compliance, and strain among small lung regions could explain the gravity-independent nonuniform regional ventilation (58) and gas mixing within lobes (85).

Quantitative analysis of volumetric chest computed tomography.

Early chest computed tomography (CT), using the dynamic spatial reconstructor, noninvasively demonstrated a ventral-to-dorsal gradient of decreasing fractional lung air content at FRC in supine but not prone posture; regional differences were caused by gravitational effects as well as structural differences and the rigidity of mediastinal contents (27, 29, 30). Subsequently, CT attenuations of air and air-free tissue were used to estimate lung weight, gas volume, and expansion. In children of different ages, volumetric CT-derived gas volume and lung weight correlated with predicted values of functional residual capacity (FRC) and postmortem lung weight, respectively; the estimated rates of lung expansion with age are consistent with the view that postnatal lungs grow initially by addition of alveolar septa, followed by gradual increases of both tissue volume and airspace size (13). Airway wall and lumen and arterial area were exponentially related to body height, whereas airway surface length/area ratio was linearly related to alveolar surface/volume ratio (12).

With the use of high-resolution CT (HRCT) and combining the attenuation of lung parenchyma with the calibrated attenuations of intrathoracic air and air-free blood-containing tissue, it is possible to partition any given volume of parenchyma into air (Vair) and tissue (Vtiss; including microvascular blood) volumes (75) and to derive the fractional tissue volume (FTV) as FTV = Vtiss/(Vtiss + Vair). This analysis can be applied voxel-by-voxel to yield topographical gradients of Vair, Vtiss, and FTV, expressed along standardized 3D coordinate axes (65, 66, 88, 89). Recently developed semiautomated lobar fissure-detection algorithms (67, 88, 90) may be added, allowing separate analysis of each natural functioning unit (lobe) as well as comparisons of regional changes with respect to their relative positions within and among lobes before and after intervention, even in the presence of gross distortion. Adding simultaneous measurement of transpulmonary pressure (Ptp) during HRCT performed at two or more inflation levels allows estimation of regional lung compliance. A more accurate assessment of regional compliance (or more complex expressions of stress distribution) requires knowledge of the constitutive properties of the lung and the precise distribution of loads that are acting on the tissue: neither of these has yet been achieved. State-of-the-art open-source nonrigid registration and analytical tools are available to match natural landmarks on successive scans and warp or “morph” paired images and permit voxelwise analysis of regional deformation characteristics by generating 3D vector field maps of displacement (motion) and strain, as well as the estimation of lobar shear (55, 89). These evolving techniques have significantly advanced our state-of-the-art ability to monitor regional anatomy noninvasively in relation to regional function.

Functional lung growth assessed by HRCT.

Few studies have quantitatively measured lung-tissue growth by HRCT in children (12, 13, 22, 63). Reference values for the CT-derived volume of each lung as a function of age and sex are available (22). In infants and toddlers up to ∼3 years of age, HRCT-derived lung air and tissue volumes increase linearly with body length and at a constant rate; central conducting airway caliber also increases in proportion to parenchyma volume and body length (64). These results confirm those from previous studies (12, 13)—that early postnatal lung growth occurs primarily by the addition of new lung units rather than by the expansion of lung units. Following pediatric lung transplantation, the relationship of tracheal diameter to body height remains normal, and the postanastomotic large airways grow similarly to native pre-anastomotic airways (69).

Regional lung growth has been quantified experimentally. In normal canine lungs during maturation (∼6–12 mo of age), growth rates among lobes are relatively uniform. Air volume increases faster than tissue volume in all regions, causing the HRCT-derived FTV to decline at a similar rate among lobes (65). This is consistent with the interpretation that the rate of airspace enlargement exceeds the rate of increase in lung tissue and blood. However, upon reaching adulthood, the lungs exhibit moderate heterogeneity in the distributions of air volume, tissue volume, and specific lung compliance within and among lobes. Mean lobar FTV is higher in the caudal and infracardiac lobes than in the cranial lobes (88), reflecting the known lobar differences in alveolar septal tissue density and in microvascular perfusion and blood volume. In addition, regional CT-derived FTV increases in the ventrodorsal and cephalocaudal directions within all lobes (88).

In young dogs following 55–58% lung resection by right PNX, intensified mechanical signals superimpose upon developmental signals, causing an ∼2.2-fold increase in CT-derived tissue-blood volume in all remaining lobes relative to control lobes of matched animals following sham PNX. The magnitude of compensatory increase in CT-derived tissue volume is consistent with the increase in septal tissue volume assessed at postmortem by morphometry (73). However, when HRCT was repeated 10 mo later upon somatic maturity, the relative increase in lobar tissue volume of the remaining left caudal lobe (twofold) fell behind that of the cranial and middle lobes (2.5- to 2.8-fold) (65). The magnitude of whole-lung post-PNX structural growth was larger and functional compensation more complete in young animals than in adults (35, 39, 73), whereas the pattern of lobar nonuniformity was similar regardless of whether PNX was performed before or after somatic maturity (65, 66). Thus the additive developmental and post-PNX signals vigorously accelerated growth of all remaining lobes but do not alter the nonuniform nature of long-term outcome.

In adult dogs following 42–45% lung resection by left PNX, some lobes expanded, whereas others did not; air and tissue volumes of the right cranial and infracardiac lobes expanded 2.2-fold above and below the heart, but the right middle and caudal lobes did not expand, and overall lung-tissue volume did not increase significantly. Following 55–58% resection by right PNX, lobar expansion was more uniform. Air and tissue volumes increased in all remaining lobes; the left cranial and middle lobes expanded 2.3- to 2.7-fold across the midline anterior to the heart, whereas the caudal lobe expanded 1.9-fold posterior to the heart. Post-PNX changes in lobar FTV estimated by HRCT parallel postmortem estimates by morphometry (66). Thus the presence of mediastinal structures and ligaments dictated the heterogeneous nature and extent of lobar expansion. When lateral lung expansion was prevented by an inflated silicone prosthesis manufactured in the shape and size of the resected lung, the remaining lung still expanded, and overall lung-tissue volume increased by ∼20% via caudal displacement of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm (87), indicating that the remaining lung did not just passively expand to fill an empty space, but the thorax also adapted to accommodate the actively growing lung when space was not readily available. Ultrastructure evidence supports a graded response to strain-related alveolar-capillary distention and recruitment, whereby following ∼45% resection, type 2 epithelial cells are the first to increase in volume (36); as strain increases further following ∼55% resection, the other septal cells are also activated, resulting in an overt increase of alveolar tissue volume.

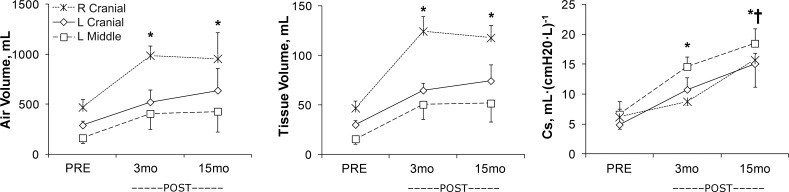

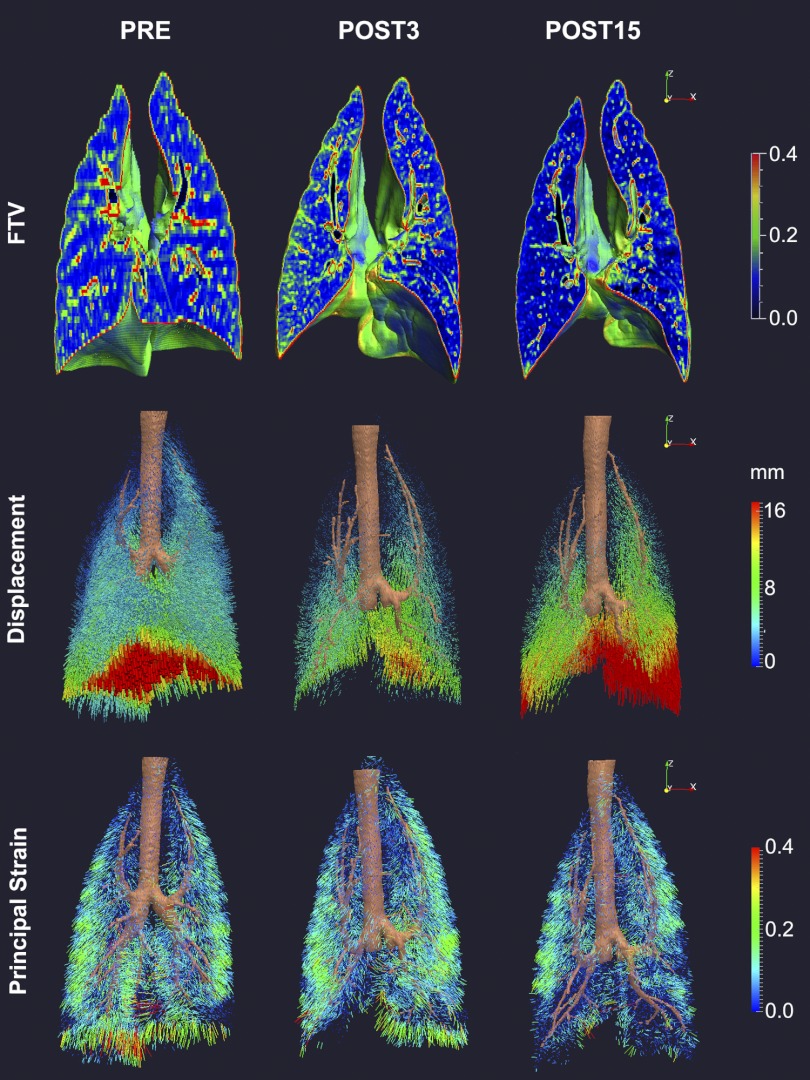

In adult dogs following two-stage balanced resection of 65–70% of total lung units (removing the caudal, infracardiac ± the middle lobes, or ∼35% from each lung without mediastinal distortion), the remaining cranial (and middle) lobes expanded in a caudal direction around and extending below the heart. HRCT-derived lobar air and tissue-blood volumes and FTV increased within 3 mo by 80–150%, 130–250%, and 30–45%, respectively, above the corresponding preresection values and remained unchanged thereafter, reflecting the increased lobar perfusion plus robust alveolar-capillary growth and resulting in early normalization of whole lung-tissue (including microvascular blood) volume (88, 89) (Fig. 1). Postresection lobar-specific compliance (Cs) doubled within 3 mo and then increased further when studied at 15 mo; consequently, whole-lung Cs normalized by 3 mo and increased further above baseline by 15 mo, suggesting a progressive decrease in tissue-stress postresection. Intralobar FTV increased heterogeneously postresection, particularly in peripheral and caudal regions, where a high FTV is associated with elevated alveolar septal-volume density and septal connective-tissue content on histology (88), suggesting that these sites experienced exaggerated mechanical stress and required greater connective-tissue support. Indeed, during passive inflation, parenchyma displacement within all lobes increased in a craniocaudal gradient, in keeping with the major direction of lobar expansion (Fig. 2). Parenchyma displacement diminished globally 3 mo postresection and then increased back to, or in the caudal regions of remaining lobes exceeded, preresection values by 15 mo. These changes indicate an initial reduction of lobar distensibility with subsequent normalization or even an increase in distensibility. Since there was no further tissue growth between 3 and 15 mo postresection, the later increase in distensibility may be attributed to gradual tissue relaxation and structural remodeling, which improved the static stress-strain relationship of the remaining lobes.

Fig. 1.

Serial high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was used to monitor lobar air and tissue volumes as well as specific compliance (Cs) calculated at 2 transpulmonary pressures (Ptp; 15 and 30 cmH2O), before (PRE) and 3 and 15 mo after (POST) 65–70% lung resection in adult dogs. In the remaining 3 lobes [right (R) and left (L) cranial and L middle], the increase in tissue volume stabilized at 3 mo, whereas Cs continued to increase, consistent with early alveolar-capillary growth and progressive remodeling, leading to continued improvement in mechanical function. Mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs. PRE; †P < 0.05 vs. 3 mo post-lung resection [adapted from Yilmaz et al. (89)].

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional color maps of regional fractional tissue volume (FTV; top panels) and vector field maps of parenchyma displacement (middle panels) and strain (bottom panels) during inflation (from 15 to 30 cmH2O)—imaged by HRCT in adult dog lung before and 3 and 15 mo after extensive (65–70%) lung resection (POST3 and POST15, respectively)—illustrate the temporal and spatial heterogeneity during early and late phases of compensation. Surgery removed 4 lobes (L and R caudal, R middle, and infracardiac lobes). The remaining 3 lobes (L and R cranial and L middle lobes) expanded markedly in a mainly caudal direction and around the mediastinum. At POST3, patchy increases in FTV, reduction in displacement, and nonuniform increases in strain developed compared with PRE. At POST15, mild, patchy reductions in FTV, markedly increased displacements, particularly in the caudal regions, and nonuniform reductions in regional strain developed compared with POST3 (88, 89).

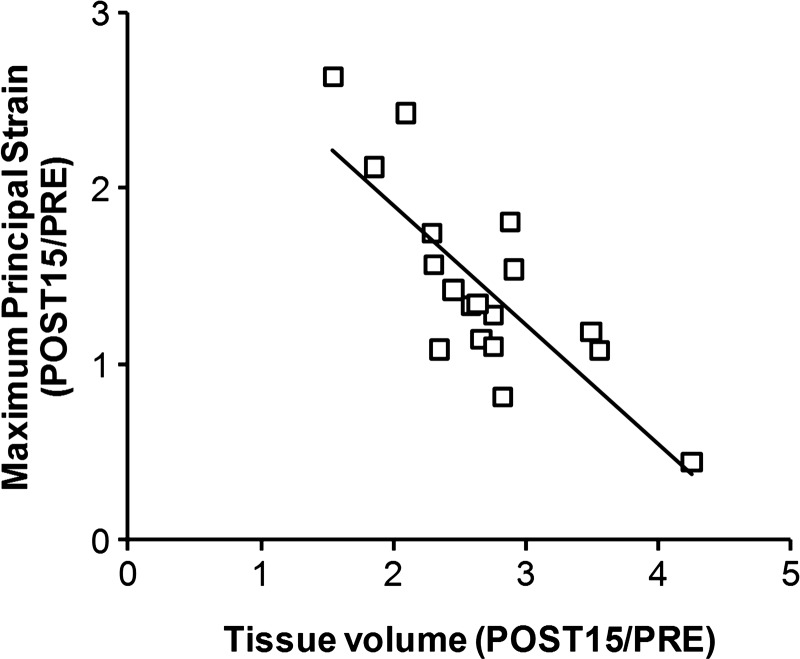

With the knowledge of the regional parenchyma displacement and Ptp changes during inflation, strain vector maps could be generated and the strain magnitude resolved along orthogonal axes (Fig. 2). In normal and postresection lungs, nonuniform strain preferentially distributes to the lobar periphery, where strong bronchovascular support is lacking; the distribution corresponds to the known pattern of more active cellular proliferation in peripheral than in central lobar regions (21, 51). Postresection strain increased nonuniformly, and the spatial pattern was altered from that preresection; strain increase was largest in the regions that expanded around the heart, especially in the left middle lobe. In normal lobes, shear distortion during inflation was minimal. Postresection, nonuniform lobar shear developed in different planes during inflation in keeping with the directions of stretch and rotation of the expanded lobes. From 3 to 15 mo postresection, there was no further change in lobar shear during inflation, whereas lobar strain either remained unchanged or continued to increase modestly and nonuniformly in different regions. Long-term postresection changes in lobar maximum principal strain and tissue growth correlated inversely—the larger the increase in tissue volume, the smaller the increase in maximum principal strain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Compensatory lung growth correlates with reduced lung strain during inflation. In adult dogs following extensive (65–70%) lung resection, the relative increase in maximum principal strain of the remaining lobes correlated inversely with the relative increase in lobar tissue volume estimated by HRCT. Data are expressed as a ratio between 15-mo postresection and the preresection baseline (POST15/PRE). y = −0.68x + 3.27; R2 = 0.62 [adapted from Yilmaz et al. (89)].

Taken together, imaging data in a large mammalian model of compensatory lung growth highlight the chronicity as well as the temporal and spatial heterogeneity of structure-function adaption, which are difficult to define from ex vivo tissue studies alone. Imaging provides visual and quantitative support for mechanotransduction as the initiating signal of compensatory lung growth and remodeling, which in turn, mitigates the expected increase in tissue stress strain in a feedback loop that continues until stress strain in all lung regions falls below some threshold level, at which point, growth and remodeling also cease. Heterogeneity of regional stress-strain responses could prolong the time course of this feedback loop, suggesting a potentially wide window of opportunity, during which the adaptive pathways remain persistently active in all or at least some regions of the remaining lobes and hence, are susceptible to exogenous manipulation (64).

Dysanaptic lung growth assessed by HRCT.

The post-PNX remaining bronchovasculature becomes grossly distorted due to rotation, splaying, and/or mediastinal displacement (11, 19, 89). Flow resistance is elevated at any given total ventilation or perfusion. The chronically elevated wall stress leads to a different kind of growth and remodeling in airway/vascular generations, comprised of lengthening followed by slower progressive dilatation. Long-term post-PNX lobar airway cross-sectional area increased 24% but was insufficient to completely offset the higher viscous resistance due to airway lengthening and a threefold higher flow resistance caused by increased turbulence and convective acceleration. Based on airway dimensions measured on HRCT and the expected increase in lobar airflow, the estimated post-PNX compensatory reduction in work of breathing (∼30%) agreed well with that measured in exercising post-PNX animals (11). With increasing severity of lung resection, work of breathing at a given minute ventilation rose steadily (34). Pulmonary arterial resistance rose in parallel, especially in the presence of mediastinal distortion (34), which can cause bronchovascular kinking and lead to morbidity and mortality. In both young and adult dogs, the slowly and incompletely adapting conducting structures confer limited functional improvement, which lags behind the improvement in gas exchange (34, 73, 74). Consequently, ventilatory resistance and pulmonary arterial resistance remain elevated long after alveolar diffusion-perfusion relationships normalize, signifying the inability to form new conducting branches in contrast to the vigorous formation of new alveolar tissue, capillaries, and surfaces. The disparity in structural adaptability, termed dysanaptic growth, is evident during normal lung development (25, 32), becomes more pronounced with increasing parenchyma stress following PNX, and constitutes the major factor that limits exercise capacity following 65–70% resection. In severe destructive lung disease, dysanaptic growth may impose an upper limit on how much functional improvement could be obtained from growth induction of the remaining alveolar units. This limit has major implications for various therapeutic attempts that aim to stimulate distal lung growth using exogenous growth-promoting compounds or stem cells.

CHALLENGES AND NEW DEVELOPMENTS

Limitations and developments in imaging.

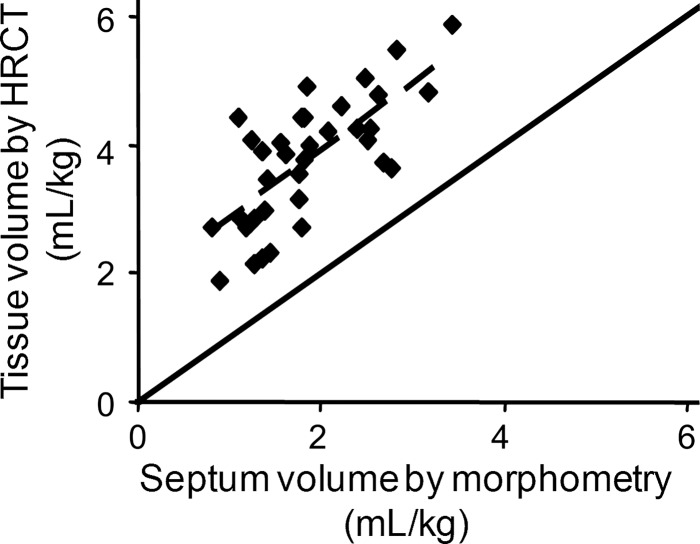

The resolution of air-tissue boundary at or below FRC by HRCT is often inadequate. Without intravenous contrast injection, extravascular tissue cannot be distinguished from microvascular blood. Separate quantification of lung-tissue and microvascular blood volumes following contrast injection remains to be validated. Because of a variable in vivo microvascular blood content, CT-derived lung-tissue volume is systematically larger than ex vivo alveolar extravascular tissue volume measured by morphometry. This observation per se is not a major drawback for the assessment of lung growth, because 1) functionally useful lung growth and compensation require balanced increases in gas-exchange tissue surfaces and capillary blood, and 2) a significant correlation exists between in vivo lung-tissue volume and ex vivo alveolar septal volume during development and post-PNX (Fig. 4) (66); these measurements, under different conditions, yield complementary data. However, in vivo and ex vivo correspondence may or may not hold in other pathophysiology and must be established individually.

Fig. 4.

Correlation of lung-tissue volume measured by HRCT (at 20 cmH2O Ptp) with alveolar septal volume measured by postmortem morphometry (tracheal instillation of fixatives at 25 cmH2O airway pressure). Solid line, identity; dashed line, regression through the data range. y = 1.06x + 1.79; R2 = 0.526 [adapted from Ravikumar et al. (66)].

Accurate detection of lobar fissures is a crucial and time-consuming step in HRCT image analysis. Ongoing improvement in automated or semiautomated lobar segmentation algorithms should facilitate the analysis. Texture-based image analysis, under development by various groups to aid the discrimination of emphysema and fibrosis (4, 28), may be combined with attenuation-based analysis to enhance the characterization of topographical growth patterns and to follow abnormal patterns. Consistent and accurate nonrigid registration of a well-distributed set of landmarks is crucial for reliable deformation vector field analysis. Lung regions near the pleura are more prone to registration errors than central lung regions (43). A plethora of nonrigid landmark registration algorithms for thoracic CT have been described; 20 of these were evaluated in an ongoing public forum, Evaluation of Methods for Pulmonary Image Registration 2010 (55), in an effort to compare them objectively and to facilitate further advances in their development.

Functional changes are usually inferred from static HRCT, performed at two or more states during breath-holding. Dynamic 4D CT is an alternative modality for functional imaging of the lung throughout the respiratory cycle without the need for breath-holding; it suffers the drawback of a lower resolution and higher radiation dose. Thus far, this modality has been used to assess lung tumor size and motion in the planning of stereotactic radiation therapy (43, 83), sometimes in combination with PET/CT (44).

Radiation exposure limits longitudinal clinical applications of functional HRCT. Alternative radiation-free imaging modalities for monitoring lung growth could be particularly useful in pediatric subjects. For example, conventional MRI with a relatively long echo-delay time cannot visualize the lung parenchyma due to a high air content causing rapid signal decay. Recent advent of 3D ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI sequence, in conjunction with a projection acquisition of the free induction decay, could reduce echo time to ∼100 μs and allow detection of inherent MRI signal intensity from lung parenchyma. Parenchyma signals have been shown to vary with lung inflation and correlate highly with tissue-blood density (80). Changes in parenchyma MRI signal intensity, due to inhalation of 100% oxygen or intravenous gadolinium contrast injection, may be combined with the UTE sequence to assess regional distributions of ventilation or perfusion, respectively (79). By registering corresponding, mostly vascular features on successive MRIs, voxelwise regional parenchyma motion may be assessed (45) in an approach similar to that used for HRCT. Currently, the resolution of parenchyma details by UTE MRI is inferior to that by HRCT, and lobar fissures cannot be detected. Further technological advances may overcome these obstacles.

Limitations in quantifying lung-tissue stress.

Mechanical stress is a measure of the internal forces that arise within a deformable body as a reaction to external forces. To quantify stress, one must know the constitutive properties of the material that is being studied and the forces that are applied to it to establish a measured strain. For many engineering materials, this is simple, as they have linear elastic properties that allow stress and strain to be related by Hooke's law. However, biological materials are rarely this straightforward because of the nonlinear elastic behavior of their constituent proteins and the complexity of their structural configuration. The lung is no exception. Stress in the context of lung growth is critical, because it is the change in stress and not strain per se that is the signal for mechanotransduction. Estimation of regional lung compliance has stood for many years as a placeholder for quantification of the 3D distribution of tissue stress. Quantifying a constitutive law that relates stress and strain in lung tissue is extremely challenging and remains incompletely addressed. A uniaxial or biaxial stretch of tissue strips can be used to define a constitutive law for other tissues (42, 76). However, because the elastic response of lung tissue depends strongly on both the alveolar configuration and the interfacial forces at the air-liquid interface, it is not clear that tissue-strip experiments, which modify one or both of these, are sufficiently accurate to define the mechanical response of the lung. An alternative approach, proposed by Denny and Schroter (14), is to construct a computational model of the lung's microstructure that includes the alveolar geometry and the spatial distribution of elastin and collagen. Elastic moduli, which are representative of the bulk tissue, can then be derived by analyzing the deformation of a block of “virtual” tissue. This approach has been extended to the emphysematous lung (59), demonstrating a link between degradation in alveolar tissue microstructure and macroscopic tissue behavior. This approach may be extended to the maturing lung or to tissue that is under abnormally high and nonuniform strain, e.g., following PNX.

Imaging-based models to interpret measurements of deformation.

Imaging-based computational models of the lung have emerged as a means of integrating experimental data across spatial scales into a quantitative framework that is biophysically based and predictive of function (10, 61). These types of model have given new insights into lung physiology and pathophysiology, e.g., Burrowes et al. (7); however, they have been developed almost exclusively for the adult lung. A noted exception from the adult models are computational models for airway morphogenesis, e.g., Tebockhorst et al. (78). The predictive power of these imaging-based models lies in their biophysical basis and their foundation in conservation laws. They can be used to explain the interaction of mechanisms over different spatial scales that give rise to experimental observations, as demonstrated by Politi et al. (61), for force development in bronchoconstriction. Following validation against data from animal studies, they can then be used to predict or explain function in the human lung, where data are less accessible.

Data defining compensatory lung growth are of course more accessible from animal studies than from human. The translation between the animal and human computational model involves no more than a change in the model geometry and definition of physiological conditions that are appropriate to the species; the underlying physics remain the same, and cellular- or molecular-level function is assumed the same across species, unless there is clear evidence that this is not the case (e.g., the behavior of mouse airway smooth muscle in contrast to rat or human). This approach has suggested important species differences in the distribution of blood in the lung related to differences in branching geometry but not the nature of the blood flow itself or the mechanisms that influence its regional delivery (8). The same approach of modeling integrative function can be extended to lung maturation and growth, although ideally, this would involve accounting for events that occur over much longer time scales than are typically considered in current lung-modeling studies.

Existing imaging-based models could be used to estimate the regional distribution of stress during lung growth. The accuracy of this estimation would depend on the accuracy of the constitutive law for the lung tissue (which as described previously, is not yet well characterized) and the accuracy of the boundary conditions that control the lung-tissue deformation. Despite the constitutive law limitation, Tawhai et al. (77) have had some success in predicting the gross response of human lung-tissue deformation to gravity in prone and supine postures using a constitutive law with relatively simple parameterization. This model was developed for human lung but is likely to be valid for animal lungs, as the basic pressure-volume response of the lung tissue is similar between species. Baseline imaging and functional measurements would provide sufficient data to confirm this or to optimize the parameters in the constitutive law to make them species and/or subject specific. The Tawhai et al. (77) model minimizes boundary condition error by using contact and sliding constraints at the lung surface instead of defining the displacement of discrete surface points. With the use of contact constraints, the lung model is free to slide within the thoracic cavity, and asymmetric expansion of lung units, such as that occurring under negative intrapleural pressure following major resection, could be simulated to yield a predicted strain field that could be validated against imaging; the corresponding stress field would also be predicted. Whereas it is not possible to directly validate the spatial distribution of stress, good evidence for its appropriateness would be given by a close correspondence between the predicted and imaged strain distribution.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants RO1 HL40070 and UO1 HL111146 (C. C. W. Hsia) and Ministry of Research, Science and Technology (New Zealand) Grant 20959-NMTS-UOA (M. H. Tawhai).

DISCLOSURES

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or of the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.C.H. and M.H.T. conception and design of research; C.C.H. and M.H.T. performed experiments; C.C.H. and M.H.T. analyzed data; C.C.H. and M.H.T. interpreted results of experiments; C.C.H. and M.H.T. prepared figures; C.C.H. and M.H.T. drafted manuscript; C.C.H. and M.H.T. edited and revised manuscript; C.C.H. and M.H.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Cuneyt Yilmaz for the preparation of HRCT images.

REFERENCES

- 1. ad hoc Statement Committee, American Thoracic Society Mechanisms and limits of induced postnatal lung growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 319–343, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Assaad AM, Kawut SM, Arcasoy SM, Rosenzweig EB, Wilt JS, Sonett JR, Borczuk AC. Platelet-derived growth factor is increased in pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Chest 131: 850–855, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berend N, Marlin GE. Arrest of alveolar multiplication in kyphoscoliosis. Pathology 11: 485–491, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blechschmidt RA, Werthschutzky R, Lorcher U. Automated CT image evaluation of the lung: a morphology-based concept. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 20: 434–442, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burri PH. Fetal and postnatal development of the lung. Annu Rev Physiol 46: 617–628, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burri PH. Structural aspects of postnatal lung development—alveolar formation and growth. Biol Neonate 89: 313–322, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burrowes KS, Clark AR, Tawhai MH. Blood flow redistribution and ventilation-perfusion mismatch during embolic pulmonary arterial occlusion. Pulm Circ 1: 365–376, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burrowes KS, Hoffman EA, Tawhai MH. Species-specific pulmonary arterial asymmetry determines species differences in regional pulmonary perfusion. Ann Biomed Eng 37: 2497–2509, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chevalier PA, Rodarte JR, Harris LD. Regional lung expansion at total lung capacity in intact vs. excised canine lungs. J Appl Physiol 45: 363–369, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clark AR, Tawhai MH, Hoffman EA, Burrowes KS. The interdependent contributions of gravitational and structural features to perfusion distribution in a multiscale model of the pulmonary circulation. J Appl Physiol 110: 943–955, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dane DM, Johnson RL, Jr, Hsia CCW. Dysanaptic growth of conducting airways after pneumonectomy assessed by CT scan. J Appl Physiol 93: 1235–1242, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Jong PA, Long FR, Wong JC, Merkus PJ, Tiddens HA, Hogg JC, Coxson HO. Computed tomographic estimation of lung dimensions throughout the growth period. Eur Respir J 27: 261–267, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Jong PA, Nakano Y, Lequin MH, Merkus PJ, Tiddens HA, Hogg JC, Coxson HO. Estimation of lung growth using computed tomography. Eur Respir J 22: 235–238, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Denny E, Schroter RC. A model of non-uniform lung parenchyma distortion. J Biomech 39: 652–663, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dobbs LG, Gutierrez JA. Mechanical forces modulate alveolar epithelial phenotypic expression. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 129: 261–266, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunnill MS. Postnatal growth of the lung. Thorax 17: 329–333, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emery JL, Mithal A. The number of alveoli in the terminal respiratory unit of man during late intrauterine life and childhood. Arch Dis Child 35: 544–547, 1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fauza DO, Hirschl RB, Wilson JM. Continuous intrapulmonary distension with perfluorocarbon accelerates lung growth in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: initial experience. J Pediatr Surg 36: 1237–1240, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fernandez LG, Le Cras TD, Ruiz M, Glover DK, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Differential vascular growth in postpneumonectomy compensatory lung growth. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 133: 309–316, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flake AW, Crombleholme TM, Johnson MP, Howell LJ, Adzick NS. Treatment of severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia by fetal tracheal occlusion: clinical experience with fifteen cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183: 1059–1066, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foster DJ, Yan X, Bellotto DJ, Moe OW, Hagler HK, Estrera AS, Hsia CCW. Expression of epidermal growth factor and surfactant proteins during postnatal and compensatory lung growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L981–L990, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gollogly S, Smith JT, White SK, Firth S, White K. The volume of lung parenchyma as a function of age: a review of 1050 normal CT scans of the chest with three-dimensional volumetric reconstruction of the pulmonary system. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29: 2061–2066, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harding R, Hooper SB. Regulation of lung expansion and lung growth before birth. J Appl Physiol 81: 209–224, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harding R, Hooper SB, Han VK. Abolition of fetal breathing movements by spinal cord transection leads to reductions in fetal lung liquid volume, lung growth, and IGF-II gene expression. Pediatr Res 34: 148–153, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hibbert M, Lannigan A, Raven J, Landau L, Phelan P. Gender differences in lung growth. Pediatr Pulmonol 19: 129–134, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Higuchi M, Hirano H, Gotoh K, Takahashi H, Maki M. Relationship of fetal breathing movement pattern to surfactant phospholipid levels in amniotic fluid and postnatal respiratory complications. Gynecol Obstet Invest 31: 217–221, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffman EA. Effect of body orientation on regional lung expansion: a computed tomographic approach. J Appl Physiol 59: 468–480, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM, Sonka M, Simon BA, Guo J, Saba O, Chon D, Samrah S, Shikata H, Tschirren J, Palagyi K, Beck KC, McLennan G. Characterization of the interstitial lung diseases via density-based and texture-based analysis of computed tomography images of lung structure and function. Acad Radiol 10: 1104–1118, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoffman EA, Ritman EL. Heart-lung interaction: effect on regional lung air content and total heart volume. Ann Biomed Eng 15: 241–257, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoffman EA, Sinak LJ, Robb RA, Ritman EL. Noninvasive quantitative imaging of shape and volume of lungs. J Appl Physiol 54: 1414–1421, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hooper SB, Han VK, Harding R. Changes in lung expansion alter pulmonary DNA synthesis and IGF-II gene expression in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 265: L403–L409, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hopper JL, Hibbert ME, Macaskill GT, Phelan PD, Landau LI. Longitudinal analysis of lung function growth in healthy children and adolescents. J Appl Physiol 70: 770–777, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsia CC. Signals and mechanisms of compensatory lung growth. J Appl Physiol 97: 1992–1998, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsia CC, Dane DM, Estrera AS, Wagner HE, Wagner PD, Johnson RL., Jr Shifting sources of functional limitation following extensive (70%) lung resection. J Appl Physiol 104: 1069–1079, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsia CC, Herazo LF, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL, Jr, Wagner PD. Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. II. VA/Q relationships and microvascular recruitment. J Appl Physiol 74: 1299–1309, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hsia CC, Johnson RL., Jr Further examination of alveolar septal adaptation to left pneumonectomy in the adult lung. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 151: 167–177, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsia CC, Johnson RL, Jr, Wu EY, Estrera AS, Wagner H, Wagner PD. Reducing lung strain after pneumonectomy impairs oxygen diffusing capacity but not ventilation-perfusion matching. J Appl Physiol 95: 1370–1378, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hsia CC, Wu EY, Wagner E, Weibel ER. Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy impairs regenerative alveolar tissue growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1279–L1287, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Fryder-Doffey F, Weibel ER. Compensatory lung growth occurs in adult dogs after right pneumonectomy. J Clin Invest 94: 405–412, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hubmayr RD, Rodarte JR, Walters BJ, Tonelli FM. Regional ventilation during spontaneous breathing and mechanical ventilation in dogs. J Appl Physiol 63: 2467–2475, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hubmayr RD, Walters BJ, Chevalier PA, Rodarte JR, Olson LE. Topographical distribution of regional lung volume in anesthetized dogs. J Appl Physiol 54: 1048–1056, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jor JW, Nash MP, Nielsen PM, Hunter PJ. Estimating material parameters of a structurally based constitutive relation for skin mechanics. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 10: 767–778, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kabus S, Klinder T, Murphy K, van Ginneken B, van Lorenz C, Pluim JP. Evaluation of 4D-CT lung registration. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 12: 747–754, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Killoran JH, Gerbaudo VH, Mamede M, Ionascu D, Park SJ, Berbeco R. Motion artifacts occurring at the lung/diaphragm interface using 4D CT attenuation correction of 4D PET scans. J Appl Clin Med Phys 12: 3502, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kiryu S, Sundaram T, Kubo S, Ohtomo K, Asakura T, Gee JC, Hatabu H, Takahashi M. MRI assessment of lung parenchymal motion in normal mice and transgenic mice with sickle cell disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 27: 49–56, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kurz H, Burri PH, Djonov VG. Angiogenesis and vascular remodeling by intussusception: from form to function. News Physiol Sci 18: 65–70, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Landesberg LJ, Ramalingam R, Lee K, Rosengart TK, Crystal RG. Upregulation of transcription factors in lung in the early phase of postpneumonectomy lung growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1138–L1149, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Langston C, Kida K, Reed M, Thurlbeck WM. Human lung growth in late gestation and in the neonate. Am Rev Respir Dis 129: 607–613, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu m Tanswell AK, Post M. Mechanical force-induced signal transduction in lung cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L667–L683, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marven SS, Smith CM, Claxton D, Chapman J, Davies HA, Primhak RA, Powell CV. Pulmonary function, exercise performance, and growth in survivors of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Arch Dis Child 78: 137–142, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Massaro GD, Massaro D. Postnatal lung growth: evidence that the gas-exchange region grows fastest at the periphery. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 265: L319–L322, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moessinger AC, Collins MH, Blanc WA, Rey HR, James LS. Oligohydramnios-induced lung hypoplasia: the influence of timing and duration in gestation. Pediatr Res 20: 951–954, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moessinger AC, Singh M, Donnelly DF, Haddad GG, Collins MH, James LS. The effect of prolonged oligohydramnios on fetal lung development, maturation and ventilatory patterns in the newborn guinea pig. J Dev Physiol 9: 419–427, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Motoyama EK, Yang CI, Deeney VF. Thoracic malformation with early-onset scoliosis: effect of serial VEPTR expansion thoracoplasty on lung growth and function in children. Paediatr Respir Rev 10: 12–17, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Murphy K, van Ginneken B, Reinhardt JM, Kabus S, Ding K, Deng X, Cao K, Du K, Christensen GE, Garcia V, Vercauteren T, Ayache N, Commowick O, Malandain G, Glocker B, Paragios N, Navab N, Gorbunova V, Sporring J, de Bruijne M, Han X, Heinrich MP, Schnabel JA, Jenkinson M, Lorenz C, Modat M, McClelland JR, Ourselin S, Muenzing SE, Viergever MA, De Nigris D, Collins DL, Arbel T, Peroni M, Li R, Sharp GC, Schmidt-Richberg A, Ehrhardt J, Werner R, Smeets D, Loeckx D, Song G, Tustison N, Avants B, Gee JC, Staring M, Klein S, Stoel BC, Urschler M, Werlberger M, Vandemeulebroucke J, Rit S, Sarrut D, Pluim JP. Evaluation of registration methods on thoracic CT: the EMPIRE10 challenge. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 30: 1901–1920, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nobuhara KK, Fauza DO, DiFiore JW, Hines MH, Fackler JC, Slavin R, Hirschl R, Wilson JM. Continuous intrapulmonary distension with perfluorocarbon accelerates neonatal (but not adult) lung growth. J Pediatr Surg 33: 292–298, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ochs M, Nyengaard JR, Jung A, Knudsen L, Voigt M, Wahlers T, Richter J, Gundersen HJ. The number of alveoli in the human lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169: 120–124, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Olson LE, Rodarte JR. Regional differences in expansion in excised dog lung lobes. J Appl Physiol 57: 1710–1714, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Parameswaran H, Majumdar A, Suki B. Linking microscopic spatial patterns of tissue destruction in emphysema to macroscopic decline in stiffness using a 3D computational model. PLoS Comput Biol 7: e101125, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Paxson JA, Parkin CD, Iyer LK, Mazan MR, Ingenito EP, Hoffman AM. Global gene expression patterns in the post-pneumonectomy lung of adult mice. Respir Res 10: 92, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Politi AZ, Donovan GM, Tawhai MH, Sanderson MJ, Lauzon AM, Bates JHT, Sneyd J. A multiscale, spatially distributed model of asthmatic airway hyper-responsiveness. J Theor Biol 266: 614–624, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rannels DE. Role of physical forces in compensatory growth of the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 257: L179–L189, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rao L, Tiller C, Coates C, Kimmel R, Applegate KE, Granroth-Cook J, Denski C, Nguyen J, Yu Z, Hoffman E, Tepper RS. Lung growth in infants and toddlers assessed by multi-slice computed tomography. Acad Radiol 17: 1128–1135, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ravikumar P, Dane DM, McDonough P, Yilmaz C, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Long-term post-pneumonectomy pulmonary adaptation following all-trans-retinoic acid supplementation. J Appl Physiol 110: 764–773, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Johnson RL, Jr, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Long-term post-pneumonectomy pulmonary adaptation following all-trans-retinoic acid supplementation. J Appl Physiol 102: 1170–1177, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Johnson RL, Jr, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Regional lung growth following pneumonectomy assessed by computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 97: 1567–1574, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Revel MP, Faivre JB, Remy-Jardin M, Deken V, Duhamel A, Marquette CH, Tacelli N, Bakai AM, Remy J. Automated lobar quantification of emphysema in patients with severe COPD. Eur Radiol 18: 2723–2730, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Riley DJ, Rannels DE, Low RB, Jensen L, Jacobs TP. NHLBI Workshop Summary. Effect of physical forces on lung structure, function, and metabolism. Am Rev Respir Dis 142: 910–914, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ro PS, Bush DM, Kramer SS, Mahboubi S, Spray TL, Bridges ND. Airway growth after pediatric lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 20: 619–624, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rodarte JR, Hubmayr RD, Stamenovic D, Walters BJ. Regional lung strain in dogs during deflation from total lung capacity. J Appl Physiol 58: 164–172, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Russo LA, Rannels SR, Laslow KS, Rannels DE. Stretch-related changes in lung cAMP after partial pneumonectomy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 257: E261–E268, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sakamaki Y, Matsumoto K, Mizuno S, Miyoshi S, Matsuda H, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor stimulates proliferation of respiratory epithelial cells during postpneumonectomy compensatory lung growth in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 26: 525–533, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Takeda S, Hsia CCW, Wagner E, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Weibel ER. Compensatory alveolar growth normalizes gas exchange function in immature dogs after pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol 86: 1301–1310, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Takeda S, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Hsia CCW. Postpneumonectomy alveolar growth does not normalize hemodynamic and mechanical function. J Appl Physiol 87: 491–497, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Takeda S, Wu EY, Epstein RH, Estrera AS, Hsia CCW. In vivo assessment of changes in air and tissue volumes after pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol 82: 1340–1348, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tawhai MH, Hunter PJ, Tschirren J, Reinhardt JM, McLennan G, Hoffman EA. CT-based geometry analysis and finite element models of the human and ovine bronchial tree. J Appl Physiol 97: 2310–2321, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tawhai MH, Nash MP, Lin CL, Hoffman EA. Supine and prone differences in regional lung density and pleural pressure gradients in the human lung with constant shape. J Appl Physiol 107: 912–920, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tebockhorst S, Lee D, Wexler AS, Oldham MJ. Interaction of epithelium with mesenchyme affects global features of lung architecture: a computer model of development. J Appl Physiol 102: 294–305, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Togao O, Ohno Y, Dimitrov I, Hsia CC, Takahashi M. Ventilation/perfusion imaging of the lung using ultra-short echo time (UTE) MRI in an animal model of pulmonary embolism. J Magn Reson Imaging 34: 539–546, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Togao O, Tsuji R, Ohno Y, Dimitrov I, Takahashi M. Ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI of the lung: assessment of tissue density in the lung parenchyma. Magn Reson Med 64: 1491–1498, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Unbekandt M, del Moral PM, Sala FG, Bellusci S, Warburton D, Fleury V. Tracheal occlusion increases the rate of epithelial branching of embryonic mouse lung via the FGF10-FGFR2b-Sprouty2 pathway. Mech Dev 125: 314–324, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Walker GM, Kasem KF, O'Toole SJ, Watt A, Skeoch CH, Davis CF. Early perfluorodecalin lung distension in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 38: 17–20, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Werner R, Ehrhardt J, Schmidt R, Handels H. Patient-specific finite element modeling of respiratory lung motion using 4D CT image data. Med Phys 36: 1500–1511, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wigglesworth JS, Desai R. Effect on lung growth of cervical cord section in the rabbit fetus. Early Hum Dev 3: 51–65, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wilson TA, Olson LE, Rodarte JR. Effect of variable parenchymal expansion on gas mixing. J Appl Physiol 62: 634–639, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wolff JC, Wilhelm J, Fink L, Seeger W, Voswinckel R. Comparative gene expression profiling of post-natal and post-pneumonectomy lung growth. Eur Respir J 35: 655–666, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wu EY, Hsia CC, Estrera AS, Epstein RH, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL., Jr Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy does not abolish physiological compensation. J Appl Physiol 89: 182–191, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yilmaz C, Ravikumar P, Dane DM, Bellotto DJ, Johnson RL, Jr, Hsia CC. Noninvasive quantification of heterogeneous lung growth following extensive lung resection by high-resolution computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 107: 1569–1578, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yilmaz C, Tustison NJ, Dane DM, Ravikumar P, Takahashi M, Gee JC, Hsia CC. Progressive adaptation in regional parenchyma mechanics following extensive lung resection assessed by functional computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 111: 1150–1158, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhang L, Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM. Atlas-driven lung lobe segmentation in volumetric X-ray CT images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 25: 1–16, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhang Q, Bellotto DJ, Ravikumar P, Moe OW, Hogg RT, Hogg DC, Estrera AS, Johnson RL, Jr, Hsia CC. Postpneumonectomy lung expansion elicits hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L497–L504, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhang S, Garbutt V, McBride JT. Strain-induced growth of the immature lung. J Appl Physiol 81: 1471–1476, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]