Abstract

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that exercise-stimulated muscle glucose uptake (MGU) is augmented by increasing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) scavenging capacity. This hypothesis was tested in genetically altered mice fed chow or a high-fat (HF) diet that accelerates mtROS formation. Mice overexpressing SOD2 (sod2Tg), mitochondria-targeted catalase (mcatTg), and combined SOD2 and mCAT (mtAO) were used to increase mtROS scavenging. mtROS was assessed by the H2O2 emitting potential (JH2O2) in muscle fibers. sod2Tg did not decrease JH2O2 in chow-fed mice, but decreased JH2O2 in HF-fed mice. mcatTg and mtAO decreased JH2O2 in both chow- and HF-fed mice. In parallel, the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) was unaltered in sod2Tg in chow-fed mice, but was increased in HF-fed sod2Tg and both chow- and HF-fed mcatTg and mtAO. Nitrotyrosine, a marker of NO-dependent, reactive nitrogen species (RNS)-induced nitrative stress, was decreased in both chow- and HF-fed sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice. This effect was not changed with exercise. Kg, an index of MGU was assessed using 2-[14C]-deoxyglucose during exercise. In chow-fed mice, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO increased exercise Kg compared with wild types. Exercise Kg was also augmented in HF-fed sod2Tg and mcatTg mice but unchanged in HF-fed mtAO mice. In conclusion, mtROS scavenging is a key regulator of exercise-mediated MGU and this regulation depends on nutritional state.

Keywords: superoxide dismutase, catalase, hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion, high-fat diet

reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated inside and outside the mitochondria. In the mitochondria they are formed when electrons escape electron transport chain and react with ground state oxygen to form the superoxide anion (O2·−). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) converts O2˙− to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is reduced to water (H2O) by the action of glutathione peroxidase or peroxiredoxins. Catalase, an antioxidant enzyme located in peroxisomes also decomposes H2O2 to H2O and oxygen. In the presence of reduced metal atoms H2O2 may be oxidized to the highly reactive hydroxyl (˙OH) or peroxyl (˙OOH) radicals (27, 35). Skeletal muscle generates ROS, and this generation is increased with insulin resistance (1, 2, 24). Paradoxically ROS production is also increased by muscle contraction (35), a condition associated with increased muscle glucose uptake (MGU) and increased insulin action (40). One distinction between insulin resistance and muscle contraction is that in the insulin resistant state increased ROS is due to formation of mitochondrial O2˙− (mtO2˙−) (2, 24), whereas recent work in isolated fibers suggest that the increment in ROS during contraction is extra-mitochondrial (26). In addition to site of origin, the specific ROS species may be significant in metabolic regulation. mtO2˙− has been implicated in insulin resistance (2, 24). On the other hand, H2O2-activated signaling pathways have been proposed to contribute to the stimulation of MGU during contraction (35, 48, 57). The significance of ROS both in insulin resistance and with contraction is controversial and largely remains unresolved.

One important reason the role of oxidative status in MGU remains unclear and conflicting results exist is that the oxidative status of a cell is highly sensitive and subject to the experimental model and design. The role of ROS in contraction-stimulated MGU has been studied ex vivo (48), in situ (34), and in humans (37). These different models have yielded different conclusions (35). Studies of human subjects are obviously of most direct relevance, but can be limited by practical considerations regarding the use of human subjects. Ex vivo and in situ models in rodents are powerful experimental systems, but have limitations. Ex vivo models lack the intact physiological interactions between muscle fibers and surrounding matrix and capillaries, whereas in situ models are usually performed in anesthetized animals using a perfusion protocol. In both cases muscle tissue is reliant on extra-physiological factors to maintain tissue and cell integrity.

Strategies for increasing antioxidant capacity that specifically focus on the removal of mitochondrial O2˙− or H2O2 have rarely been evaluated in the context of contracting muscle. This is important in defining potential mechanisms involved in stimulating MGU. One study showed that overexpression of SOD2, the mitochondrial form of SOD, stimulates MGU in isolated contracting muscle (48). SOD2 overexpression has been shown to enhance mitochondrial antioxidant capacity and provide resistance against factors that induce mitochondrial permeability (39, 51). It has also been shown that high-fat (HF)-fed insulin resistant obese mice, which have accelerated mtROS production (2), have decreased exercise capacity and exercise-induced MGU (15). The aim of the present studies was to test the hypotheses that an increase in mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) scavenging would increase exercise-stimulated MGU in vivo. Mice overexpressing SOD2 (sod2Tg) were used to increase mtO2˙− scavenging (41). Mice expressing a catalase transgene (mcatTg) with a mitochondrial localization sequence (50) were used to increase mitochondrial H2O2 (mtH2O2) scavenging. Mice overexpressing both SOD2 and mCAT (mtAO) were also studied, representing an extremely high mitochondrial antioxidative capacity state. Exercise-stimulated MGU was measured in unstressed chronically catheterized mice, which allows for study of the whole organism and preservation of the physiological milieu. Mice fed chow or a HF diet that accelerates ROS production were combined with the transgenic mouse models to dissect the importance of pathways for ROS scavenging and to test the hypothesis that MGU is improved by increased mtROS scavenging capacity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse Models

All mice were housed in cages under conditions of controlled temperature and humidity with a 12:12-h light/dark cycle. Four lines of sex- and littermate-matched C57BL/6J mice, wild type (WT), mice overexpressing SOD2 (sod2Tg), the mitochondrial isoform of SOD (41), mice overexpressing catalase targeted to mitochondria with a mitochondrial localization signal in the human catalase transgene (mcatTg) (50), and mice with overexpression of both SOD2 and mCAT (mtAO) were used. Mice used in experiment 1 were fed chow and mice used in experiment 2 were fed a HF diet (F3282, BioServ), which contains 60% calories as fat, for 16 wk. mcatTg mice were generously provided by Dr. Peter Rabinovitch of the University of Washington (50). The Vanderbilt and East Carolina Animal Care and Use Committees approved procedures involving animals.

Exercise Stress Test

Two days prior to the exercise stress test, mice performed a 10 min bout of exercise at 10 m/min for acclimation purposes. V̇o2 was measured on an enclosed treadmill using an Oxymax System (Columbus Instruments). Following a 45-min sedentary period, mice commenced running at 10 m/min. Speed was increased 4 m/min every 3 min until exhaustion (30, 31). Sedentary V̇o2 was measured for the last 15 min of the sedentary period, and peak V̇o2 during exercise was achieved when V̇o2 no longer increased despite an increase in work rate.

Exercise Metabolism in Vivo

Metabolic studies were conducted on 149 WT, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice. Experiment 1 used 73 mice fed chow, and experiment 2 used 76 mice fed a HF diet. Catheters were implanted in the left carotid artery and the right jugular vein for sampling and infusions, respectively, >5 days before the study (5, 6). The day before surgery, all mice were acclimated to the treadmill. On the day of the study, tubing was connected to the exteriorized catheters and mice were put in the enclosed treadmill to acclimate (16). At time 0, a baseline blood sample was taken to measure arterial glucose, insulin, non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA), and lactate. Mice remained sedentary or performed a single bout of exercise at 12 m/min for 30 min. This particular speed reflects 30% of the maximal running speed in the chow-fed mice (experiment 1) and 50% of the maximal running speed in the HF-fed mice (experiment 2). The same absolute amount of work and not the relative amount of work was used regardless of diet. This made direct comparison between different diets difficult. On the other hand, mice regardless of diet performed comparable absolute work, creating similar demands on energy producing processes. All mice from the exercise group completed the 30 min treadmill running.

An index of MGU was determined using 13 μCi of 2-[14C]-deoxyglucose ([14C]2-DG) administered as an intravenous bolus at t = 5 min. Blood samples were then taken at 7, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min to measure arterial glucose and plasma [14C]2-DG. Plasma insulin, NEFA, and lactate were also measured in blood sample collected at 30 min as the postexperimental parameters. After the last sample, mice were anesthetized and tissues were excised and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Analyses

[14C]2-DG and [14C]2-DG-phosphate radioactivity.

Radioactivity of [14C]2-DG and [14C]2-DG-phosphate ([14C]2-DG-P) was determined as described (4). The fractional uptake of [14C]2-DG (Kg) was calculated by the equation: Kg = [14C]2-DG-Ptissue/AUC[14C]2-DGplasma, where [14C]2-DG-Ptissue is the [14C]2-DG-P radioactivity in tissues (dpm/g), and AUC[14C]2-DGplasma is the area under the plasma [14C]2-DG disappearance curve (dpm·min−1·ml−1).

Plasma insulin and substrates.

Plasma insulin and NEFA were determined as described (28). Plasma lactate was determined enzymatically (33). Blood glucose was determined from ∼5 μl of arterial blood using an ACCU-CHEK monitor.

Muscle glycogen.

Glycogen was measured in neutralized gastrocnemius extracts. Glucose units were determined enzymatically (33).

Muscle nitrotyrosine.

Nitrotyrosine was assessed in the fasted state and following exercise by immunohistochemistry in paraffin-embedded tissue sections (5 μm) with anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Millipore). Images were captured using a Q-Imaging Micropublisher camera mounted on an Olympus upright microscope. Immunostaining was quantified using ImageJ software.

AMPK activity.

AMPK activity was determined as previously described (59). AMPK activity was calculated as picomoles phosphate incorporated into the SAMS peptide per minute per milligram of protein.

Mitochondrial H2O2 Emitting Potential

Mitochondrial H2O2 emitting potential (JH2O2) was measured in permeabilized muscle fiber bundles prepared as described (2). Muscle fiber bundles in a buffer containing 105 mM K-MES, 30 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, pH 7.4, 5 μM glutamate, and 2 μM malate were treated with 20 mM pyrophosphate to deplete adenine nucleotides and to inhibit contraction of the fibers. JH2O2 was measured at 30°C in response to increasing succinate concentrations or 25 μM palmitoyl-carnitine and 2 mM malate during state 4 respiration (10 μg/ml oligomycin) by continuous spectrofluorometric monitoring oxidation of Amplex Red (10 μM). Exogenous Cu/Zn SOD (for the detection of non-matrix sources of superoxide production) was not included in the assay to isolate the effects of the SOD2 transgenic mouse model. JH2O2 was expressed as picomoles per minute per milligram dry weight.

Western Blotting

Isolated mitochondria samples were used for the detection of SOD2 and catalase proteins. Muscle mitochondria were isolated from frozen tissues using the Mitochondria Extraction Kit (IMGENEX). Protein concentration was then measured using a Bio-Rad assay with BSA as a standard. The absence of protein GAPDH was used to document the purity of mitochondria fractions. Protein (30 μg) was applied to 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel using the NuPAGE system (Invitrogen). SOD2 protein was probed using the SOD2 polyclonal antibody (Assay Designs). Catalase was probed using the monoclonal anti-catalase antibody (Sigma). V-DAC was used as a loading control. For the detection of hexokinase II (HKII) and GLUT4, gastrocnemius muscle was homogenized in homogenization buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was then determined, and homogenates were run on SDS-PAGE gels. HKII and GLUT4 were probed using HKII and GLUT4 antibodies (Abcam).

Reduced and Oxidized Glutathione Measurements

Gastrocnemius was homogenized in buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 5 μg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM sodium fluoride. For oxidized glutathione (GSSG) measurement, 5 mM 1-methyl-2-vinylpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate was used to scavenge all reduced thiols in the sample. Total reduced glutathione (GSH) and GSSG concentrations were then measured using the BIOXYTECH GSH/GSSG-412 assay kit (Oxis Research).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using either student's t-test or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc tests as appropriate. The significance level was P < 0.05.

RESULTS

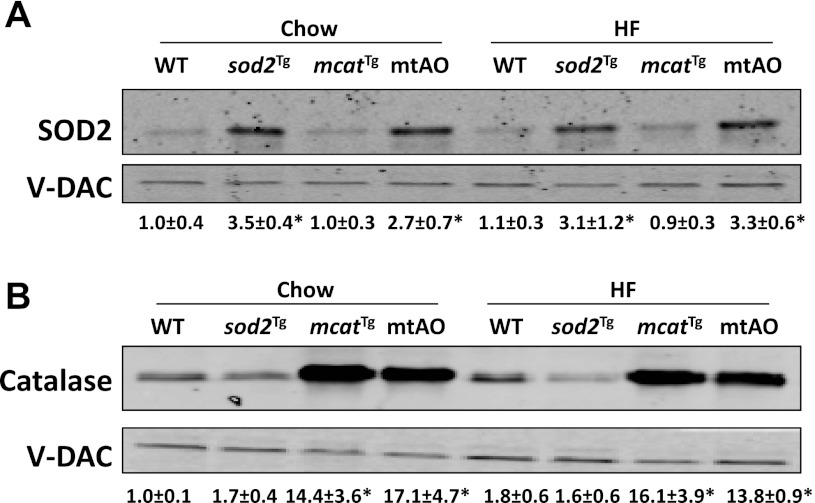

Protein Expression of SOD2 and Catalase in the Transgenic Mice

SOD2 protein expression was increased by approximately threefold in muscle mitochondria of sod2Tg and mtAO mice relative to WT mice (Fig. 1A). SOD2 protein was not affected in the mitochondria of muscle in mcatTg mice. mcatTg and mtAO mice had a ∼15-fold increase in catalase expression in muscle mitochondria compared with WT mice (Fig. 1B). Catalase protein was equal in sod2Tg and WT mice. HF feeding in mice had no effect on SOD2 or catalase expression in muscle mitochondria (Fig. 1, A and B).

Fig. 1.

Protein expression of SOD2 and catalase. Western blotting of SOD2 (A) and catalase (B) in mitochondria isolated from gastrocnemius muscle in mice after chow or high-fat diet (HF) feeding for 16 wk. Integrated intensities of bands are listed below each band and are represented as means ± SE. Data are normalized to chow-fed wild type (WT). V-DAC expression was not affected by genotype or HF feeding and was used as a loading control. N is equal to 3–8, and *P < 0.05 compared with chow-fed WT.

Experiment 1: Increased Mitochondrial Antioxidant Capacity in Chow-Fed Mice

Baseline metabolic parameters.

Body weight was unaffected by genotype (Table 1). Basal arterial glucose, plasma insulin, and NEFA were similar between all genotypes. Basal lactate was similar between genotypes except that mtAO had lower lactate, possibly reflecting a reduced redox state or a more efficient oxidation of pyruvate.

Table 1.

Characteristics of chow-fed sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice in sedentary and exercise states

| Sedentary |

Exercise |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | sod2Tg | mcatTg | mtAO | WT | sod2Tg | mcatTg | mtAO | |

| N (female/male) | 8 (4/4) | 7 (4/3) | 10 (5/5) | 7 (4/3) | 11 (5/6) | 10 (5/5) | 12 (7/5) | 8 (4/4) |

| Body weight, g | 26 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 26 ± 2 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | ||||||||

| Basal | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.3 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 10.0 ± 0.9 | 9.8 ± 0.4 | 9.1 ± 0.7 |

| Postexperimental | 10.0 ± 0.6 | 10.6 ± 0.6 | 10.6 ± 0.4 | 9.9 ± 0.4 | 12.2 ± 0.6† | 13.6 ± 0.6† | 13.1 ± 0.7† | 12.0 ± 1.0† |

| Insulin, ng/m | ||||||||

| Basal | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

| Postexperimental | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.04† | 0.45 ± 0.06† | 0.42 ± 0.05† | 0.38 ± 0.04† |

| NEFA, mM | ||||||||

| Basal | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.25 | 1.46 ± 0.17 | 1.29 ± 0.27 | 1.43 ± 0.41 | 1.36 ± 0.28 | 1.42 ± 0.12 | 1.39 ± 0.23 |

| Postexperimental | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 1.11 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.15 | 0.75 ± 0.13† | 0.73 ± 0.11† | 0.71 ± 0.09† | 1.02 ± 0.10 |

| Lactate, mM | ||||||||

| Basal | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 0.86 ± 0.17 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.07* | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 1.01 ± 0.22 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.03* |

| Postexperimental | 1.02 ± 0.20 | 0.92 ± 0.31 | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 0.55 ± 0.07* | 2.72 ± 0.38† | 2.33 ± 1.24† | 2.35 ± 0.07† | 1.18 ± 0.1†* |

Values are mean ± SE. Basal refers to data from samples collected at 0 min. Postexperimental refers to data from samples collected at 30 min.

P < 0.05 compared with wild type (WT);

P < 0.05 compared with basal.

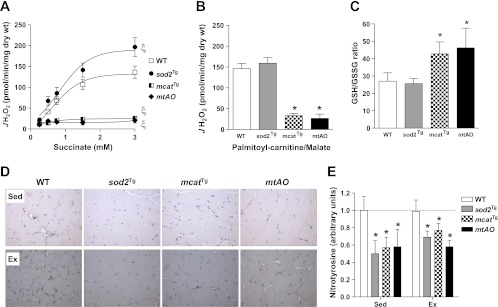

Antioxidant capacity.

Succinate-supported JH2O2 was increased in sod2Tg but decreased to baseline in mcatTg and mtAO mice (Fig. 2A). Palmitoyl-carnitine/malate-supported JH2O2 was unaffected in sod2Tg but remarkably decreased in mcatTg and mtAO mice (Fig. 2B). Results in mcatTg and mtAO mice demonstrate that expression of catalase in mitochondria is effective in scavenging mtH2O2.

Fig. 2.

Antioxidant capacity in chow-fed mice. A and B: muscle mitochondrial H2O2 emitting potential (JH2O2) was measured in permeabilized gastrocnemius fiber bundles prepared from sedentary chow-fed WT, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice. JH2O2 was measured either in response to increasing succinate concentrations (A) or 25 μM palmitoyl-carnitine and 2 mM malate (B) during state 4 respiration (10 μg/ml oligomycin). C: GSH/GSSG ratio was determined in muscle homogenates. D: protein expression of nitrotyrosine was detected by immunohistochemistry in gastrocnemius. Representative images were displayed and the magnification of images was ×20. E: nitrotyrosine protein was quantified by the integrated intensity of staining and normalized to WT chow. Data are expressed as means ± SE and n = 3–9 for each group. ξP < 0.05 for genotype effect compared with WT. *P < 0.05 compared with chow-fed WT.

The ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) was not changed in sod2Tg but was increased in mcatTg and mtAO mice (Fig. 2C). These results are parallel to the JH2O2 data as GSH participates in the detoxification of H2O2 by glutathione peroxidases. In contrast to some findings (20) but consistent with others (34), GSSG concentration was undetectable in mice after exercise.

Nitrotyrosine is a product of tyrosine nitration of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as peroxynitrite anion and nitrogen dioxide, both of which are formed in vivo by the reaction of the free radical O2˙− and the free radical nitric oxide (NO). Nitrotyrosine was decreased in sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice in the fasted stated (Fig. 2, D and E). This relationship was not affected by exercise (Fig. 2, D and E). Together these data show that overexpression of SOD2 and catalase decreases intramyocellular oxidative stress.

Exercise capacity.

Although sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO altered mitochondrial antioxidant capacity, running time to exhaustion during an exercise stress test was unaltered (20 ± 2 min in WT, 15 ± 3 min in sod2Tg, 19 ± 1 min in mcatTg, and 16 ± 1 min in mtAO). Sedentary V̇o2 was similar between genotypes (79 ± 3 in WT, 84 ± 7 in sod2Tg, 73 ± 2 in mcatTg, and 83 ± 3 ml·kg−1·min−1in mtAO). During the exercise stress test, peak V̇o2 was similar in WT, mcatTg, and mtAO mice but was lower in the sod2Tg mice [131 ± 3 in WT, 117 ± 3 (P < 0.05 vs. WT) in sod2Tg, 124 ± 3 in mcatTg, and 128 ± 5 ml·kg−1·min−1in mtAO].

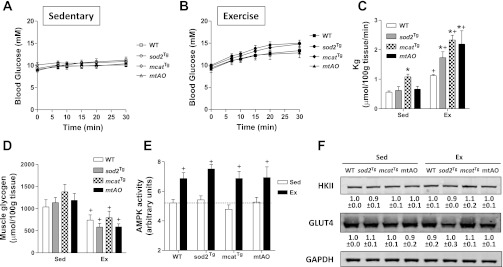

Metabolic responses to exercise.

Mice in the sedentary groups maintained arterial glucose, plasma insulin, NEFA, and lactate constant (Table 1 and Fig. 3A). Thirty minutes of exercise increased arterial glucose and lactate and decreased plasma insulin in all genotypes (Table 1 and Fig. 3B). Exercise arterial glucose and plasma insulin did not differ between genotypes, and exercise plasma lactate in mtAO mice was lower than that of WT mice. Plasma NEFA was decreased to a similar extent in WT, sod2Tg, and mcatTg mice, but was unchanged in chow-fed mtAO mice (Table 1).

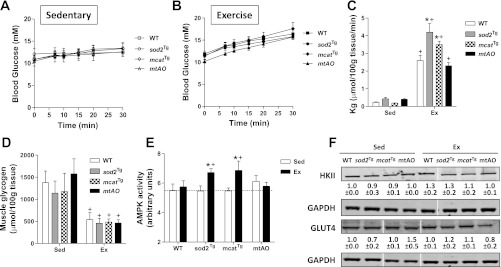

Fig. 3.

Metabolic responses to treadmill exercise in chow-fed mice. A and B: arterial glucose concentrations either at sedentary or during exercise were measured by a glucose meter in chow-fed mice. C: Kg was determined in gastrocnemius using the nonmetabolizable glucose analog 2-[14C]-deoxyglucose during the sedentary (Sed) or treadmill exercise (Ex) study in mice fed chow diet. D: muscle glycogen content was measured by an enzymatic assay in gastrocnemius collected immediately after the sedentary or exercise study from mice fed chow diet. E: AMPK activity was determined in gastrocnemius muscle collected immediately after the sedentary or exercise study. F: HKII and GLUT4 expression in muscle homogenates. Integrated intensities of bands are listed below each band. Data are expressed as means ± SE and n = 7–12 for blood glucose and Kg measurements, 4–5 for muscle glycogen and AMPK activity measurements, n = 3 for HKII and GLUT4 expression. *P < 0.05 compared with WT within Sed or Ex. +P < 0.05 compared with Sed within a genotype.

Sedentary Kg was the same among WT, sod2Tg, and mtAO mice, but was higher in mcatTg mice (Fig. 3C). Thirty minutes of exercise increased muscle Kg in all mice. Compared with WT mice, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice had enhanced exercise Kg in gastrocnemius. Muscle glycogen was similar at rest between all genotypes, and 30 min of treadmill exercise equivalently decreased glycogen in all genotypes (Fig. 3D).

Increased AMPK activity is a well-characterized response to exercise (18, 44, 63). Sedentary muscle AMPK activity was equivalent in all genotypes (Fig. 3E). Thirty minutes of exercise increased AMPK activity similarly in chow-fed WT, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice.

MGU is regulated by the delivery of glucose from the blood to the interstitial space, glucose transport across the membrane by GLUT4, and intracellular phosphorylation of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate by hexokinase II (HKII) (60, 61). Despite increased exercise Kg in the transgenic mice, muscle HKII and GLUT4 expression was similar in chow-fed WT, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice (Fig. 3F).

Experiment 2: Increased Mitochondrial Antioxidant Capacity in HF-Fed Mice

Baseline metabolic parameters.

Body weight was unaffected by genotype (Table 2). Arterial glucose, plasma insulin, NEFA, and lactate were similar in all genotypes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of HF-fed sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice in sedentary and exercise states

| Sedentary |

Exercise |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | sod2Tg | mcatTg | mtAO | WT | sod2Tg | mcatTg | mtAO | |

| N (female/male) | 9 (5/4) | 8 (4/4) | 7 (4/3) | 7 (4/3) | 11 (5/6) | 11 (6/5) | 12 (7/5) | 11 (6/5) |

| Body weight, g | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 3 | 39 ± 3 | 41 ± 4 | 39 ± 2 | 37 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 | 39 ± 3 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | ||||||||

| Basal | 10.9 ± 0.5 | 12.1 ± 1.3 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 11.9 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 0.4 | 11.4 ± 0.7 | 10.2 ± 0.4 |

| Postexperimental | 12.1 ± 0.5 | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 12.5 ± 0.7 | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 14.8 ± 0.7† | 14.3 ± 0.3† | 15.2 ± 0.9† | 13.5 ± 0.5† |

| Insulin, ng/m | ||||||||

| Basal | 1.90 ± 0.04 | 1.92 ± 0.54 | 2.40 ± 0.74 | 2.13 ± 0.93 | 2.29 ± 0.22 | 1.82 ± 0.38 | 1.75 ± 0.34 | 1.88 ± 0.42 |

| Postexperimental | 1.96 ± 0.23 | 1.79 ± 0.64 | 2.88 ± 0.88 | 1.98 ± 1.02 | 1.04 ± 0.15† | 0.64 ± 0.1†* | 0.58 ± 0.1†* | 1.00 ± 0.16† |

| NEFA, mM | ||||||||

| Basal | 1.10 ± 0.20 | 1.01 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.79 ± 0.12 | 1.09 ± 0.19 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.96 ± 0.10 |

| Postexperimental | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.58 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.09 |

| Lactate, mM | ||||||||

| Basal | 0.84 ± 0.14 | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 1.10 ± 0.28 | 0.81 ± 0.32 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 1.05 ± 0.10 | 0.96 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.04 |

| Postexperimental | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 1.25 ± 0.34 | 0.98 ± 0.07 | 2.05 ± 0.22† | 2.85 ± 0.46† | 2.44 ± 0.26† | 3.07 ± 0.2†* |

Values are mean ± SE. Basal refers to data from samples collected at 0 min. Postexperimental refers to data from samples collected at 30 min.

P < 0.05 compared with WT;

P < 0.05 compared with basal.

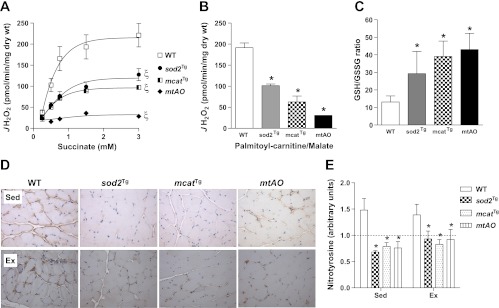

Antioxidant capacity.

HF diet elevated both succinate- and palmitoyl-carnitine/malate-supported JH2O2 in the muscle of WT mice (succinate: 221 ± 28 vs. 136 ± 15 pmol·min−1·mg−1 at 3 mM succinate, P < 0.05; palmitoyl-carnitine/malate: 192 ± 11 vs. 146 ± 13 pmol·min−1·mg−1, P < 0.05). In contrast to increased succinate-supported JH2O2 and unaltered palmitoyl-carnitine/malate-supported JH2O2 in chow-fed sod2Tg mice, both of these were decreased by ∼40% in HF-fed sod2Tg mice compared with HF-fed WT mice (Fig. 4, A and B). Succinate- and palmitoyl-carnitine/malate-supported JH2O2 was decreased by ∼60% in mcatTg mice and was decreased to baseline rates in HF-fed mtAO mice (Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4.

Antioxidant capacity in HF-fed mice. A and B: muscle mitochondrial H2O2 emitting potential (JH2O2) was measured in permeabilized gastrocnemius fiber bundles prepared from sedentary HF-fed WT, sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice. JH2O2 was measured either in response to increasing succinate concentrations (A) or 25 μM palmitoyl-carnitine and 2 mM malate (B) during state 4 respiration (10 μg/ml oligomycin). C: GSH/GSSG ratio was determined in muscle homogenates. D: protein expression of nitrotyrosine was detected by immunohistochemistry in gastrocnemius. Representative images were displayed and the magnification of images was ×20. E: nitrotyrosine protein was quantified by the integrated intensity of staining and normalized to WT chow. Data are expressed as means ± SE and n = 3–9 for each group. ξP < 0.05 for genotype effect compared with WT. *P < 0.05 compared with HF-fed WT.

HF diet feeding decreased GSH/GSSG ratio in muscle of WT mice (13 ± 3 vs. 27 ± 5, P < 0.05). GSH/GSSG ratio was increased in HF-fed sod2Tg, mcatTg and mtAO mice relative to HF-fed WT mice (Fig. 4C). GSSG concentration was undetectable in mice after exercise.

HF diet increased muscle nitrotyrosine in WT mice (1.42 ± 0.19-fold increase, P < 0.05). Nitrotyrosine was reduced in HF-fed sod2Tg, mcatTg, and mtAO mice compared with HF-fed WT mice in the fasted state (Fig. 4, D and E). This effect was not changed with exercise (Fig. 4, D and E). These data show that mitochondria-targeted increase in the antioxidant capacity effectively decreases the oxidative state of muscle in HF-fed mice.

Exercise capacity.

HF feeding equivalently impaired exercise tolerance in all genotypes (12 ± 1 in WT, 13 ± 2 in sod2Tg, 12 ± 1 in mcatTg, and 11 ± 1 min in mtAO). V̇o2 was similar between genotypes in both sedentary (76 ± 5 in WT, 98 ± 7 in sod2Tg, 81 ± 5 in mcatTg, and 91 ± 6 ml·kg−1·min−1 in mtAO) and peak exercise states (101 ± 6 in WT, 117 ± 11 in sod2Tg, 109 ± 5 in mcatTg, and 113 ± 6 ml·kg−1·min−1 in mtAO).

Metabolic responses to exercise.

The running speed of 12 m/min corresponded to 30% of maximal speed in the chow-fed mice and 50% in HF-fed mice. Because HF diet feeding decreased exercise capacity, HF-fed mice ran at a higher relative work rate although they ran at the same absolute speed as the chow-fed mice. Arterial glucose, plasma insulin, NEFA, and lactate remained constant in the sedentary groups (Table 2 and Fig. 5A). Exercise arterial glucose and plasma NEFA did not differ between genotypes (Table 2 and Fig. 5B). Exercise plasma insulin in sod2Tg and mcatTg mice was significantly lower than that of WT mice (Table 2). In contrast to chow-fed mice, exercise lactate was higher in mtAO mice relative to WT on a HF diet (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Metabolic responses to treadmill exercise in HF-fed mice. A and B: arterial glucose concentrations either at sedentary or during exercise were measured by a glucose meter in HF-fed mice. C: Kg was determined in gastrocnemius using the nonmetabolizable glucose analog 2-[14C]-deoxyglucose during the sedentary (Sed) or treadmill exercise (Ex) study in mice fed HF diet. D: muscle glycogen content was measured by an enzymatic assay in gastrocnemius muscle collected immediately after the sedentary or exercise study from mice fed HF diet. E: AMPK activity was determined in gastrocnemius muscle collected immediately after the sedentary or exercise study. F: HKII and GLUT4 expression in muscle homogenates. Integrated intensities of bands are listed below each band. Data are expressed as means ± SE and n = 7–12 for blood glucose and Kg measurements, 4–5 for muscle glycogen and AMPK activity measurements, n = 3 for HKII and GLUT4 expression. *P < 0.05 compared with WT within Sed or Ex. +P < 0.05 compared with Sed within a genotype.

Sedentary Kg was similar and exercise increased Kg in HF-fed mice of all genotypes (Fig. 5C). Exercise Kg in HF-fed mice was higher than that in the chow-fed mice with the exception of the mtAO mice (Fig. 5C vs. Fig. 3C). This is likely due to increased relative work load in the HF-fed mice. Exercise Kg, however, was enhanced in HF-fed sod2Tg and mcatTg mice compared with HF-fed WT mice but unchanged in HF-fed mtAO mice. Muscle glycogen was similar at rest and with exercise between all genotypes (Fig. 5D).

In WT mice, HF feeding abolished the exercise-induced increase in muscle AMPK activity present in chow-fed mice (Fig. 5E). This increase in AMPK activity was restored in sod2Tg and mcatTg mice. In contrast, muscle AMPK activity in mtAO mice was not restored but remained unchanged as in WT mice. The restoration of AMPK responses to exercise in HF-fed sod2Tg and mcatTg mice paralleled the increases in exercise-stimulated Kg in these mice. The failure to see an increase in AMPK activity in HF-fed mtAO was consistent with the absence of an enhanced Kg in HF-fed mtAO mice.

Consistent with chow-fed mice, muscle HKII and GLUT4 expression was not different between WT mice and the transgenic mice on a HF diet (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

These studies show that increased antioxidant capacity of muscle mitochondria by genetic means can increase MGU during exercise. There are two distinct aspects of these studies that make it particularly novel. First, we used serial genetic manipulations to distinguish mtO2˙− scavenging by SOD2 from changes in mtH2O2 formation. This is significant because H2O2 is an important signaling molecule. Second, we determined the effects of mitochondrial antioxidant capacity during exercise in an in vivo system. This is important because it permitted the study of mitochondrial oxidative status under physiological conditions free of the constraints imposed by in vitro experimental systems. Exercise has been widely used to assess cellular and molecular adaptations in muscle (7). The novel catheterized mouse model we used permits blood sampling during exercise. Exercise intensity and whether stress is induced are extremely important in examining physiological responses to exercise. In the current study we used a treadmill running protocol at 12 m/min at 0% grade for 30 min (30% maximal running speed in chow-fed mice and 50% maximal running speed in HF-fed mice). ROS signaling is highly sensitive to experimental conditions. The use of physiological exercise rather than ex vivo (48) or in situ (34) contractions may contribute to the experimental outcome and explain differing results (35).

Experiment 1: Increased Mitochondrial Antioxidative Capacity on Muscle Glucose Metabolism

Increased mitochondrial antioxidant capacity in mcatTg and mtAO mice was evident by decreased JH2O2 from muscle fibers of sedentary mice. It is important to emphasize that JH2O2 was measured in situ under conditions in which the redox pressure on the electron transport system was progressively increased (succinate titration/palmitoyl-carnitine) and thus only represents a measure of the potential for JH2O2. There are no methods available to measure mtO2˙− or mtH2O2 production in vivo in real time. Increased mitochondrial antioxidant capacity in mcatTg and mtAO mice resulted in increased intracellular antioxidant capacity as shown by increased GSH/GSSG, the major intracellular redox buffer. In contrast to mcatTg and mtAO mice, sod2Tg mice did not increase mtH2O2 scavenging. This is not surprising because SOD2 converts mtO2˙− to mtH2O2 production. Despite unchanged GSH/GSSG in sedentary sod2Tg mice, the expression of nitrotyrosine, the reaction product of mtO2˙− and NO, was decreased. Taken together, these data suggest that overexpression of the antioxidant enzymes SOD2 and catalase in mitochondria induces chronic elevation in muscle antioxidant capacity, which may not uniformly exhibit changes in acute indices of oxidative status.

Despite this increase in the antioxidant capacity, the transgenic mice have unaltered peak exercise capacity when assessed by an incremental exercise test. Results in both rodents (23, 56) and humans (64) have shown that increased antioxidative capacity by antioxidant vitamin C or E supplementation does not alter endurance training adaptation. However, studies by Ristow et al. (46) in humans and Gomez-Cabrera et al. (21) in both humans and rats reported that the same supplementation hampers training-induced adaptive responses of mitochondrial biogenesis, insulin action, and endurance capacity. This is at odds with a rodent study indicating a beneficial effect of vitamin E supplementation on endurance capacity in aging rats (3). These disparities could be due to differences in the dosage of the supplements used or other technical differences. The role of antioxidant capacity in exercise capacity remains to be clearly defined.

An increase in AMPK activity during exercise is well established (18, 44, 63). However, the role of AMPK in the coupling of ROS to MGU is controversial. While one study suggests that ROS accelerates contraction-mediated MGU by activating AMPK (48), another elegantly showed that N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a non-specific antioxidant, inhibits contraction-stimulated MGU independent of AMPKα2 (36). Exercise-stimulated MGU was enhanced in mice with increased mtROS scavenging although the exercise-mediated AMPK activation in chow-fed mice was not. This disassociation of AMPK signaling and MGU is consistent with the finding of Merry et al. (36). The discrepancy between our results and those of Sandstrom et al. (48) could be attributed to differences in the experimental paradigm. NAC was used by Sandstrom et al. to simultaneously reduce both mtROS and extra-mtROS. This approach contrasts with that of the present study where we targeted the mitochondria specifically with increased endogenous antioxidant capacity by overexpressing the antioxidant enzymes SOD2 and catalase. In addition, in vivo treadmill exercise was used in the present study, whereas ex vivo contraction was used by Sandstrom et al. (48).

MGU is regulated by the delivery of glucose from the blood to the interstitial space, glucose transport across the membrane by GLUT4, and phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate by HKII (60, 61). Membrane transport is the primary barrier to MGU in the fasted, sedentary state, as membrane GLUT4 content is low and the membrane is relatively impermeable to glucose. GLUT4 translocation is greatly increased during exercise, resulting in a shift in the barrier of MGU from membrane transport to phosphorylation (13). Indeed, we found no differences in GLUT4 expression between WT mice and the transgenic mice. We did not measure GLUT4 in the plasma membrane; however, it is unlikely based on data obtained in mice (12–14, 17), rats (22), and humans (29, 43) that increased GLUT4 translocation would further increase MGU during exercise. HK exerts greater control of MGU during exercise (13). Although we did not find differences in total HKII expression between genotypes, it has been suggested that HK compartmentation and spatial barriers also determine the ability of HKII to phosphorylate glucose (61). We speculate that these events may be affected in the transgenic mice contributing to increased exercise Kg. It is also possible that overexpression of SOD2 and/or catalase in mitochondria changes the expression of other genes that could conceivably impact our results through undefined mechanisms.

Experiment 2: Effect of Chronic Increase in Antioxidative Capacity in Muscle Mitochondria of HF-Fed Insulin Resistant Mice

The absence of the enhanced exercise Kg in HF-fed mtAO mice contrasts with the enhanced Kg in chow-fed mtAO mice and in other HF-fed transgenic mice. This remarkable finding adds important insight into the mechanisms by which oxidative status influences metabolic regulation. HF diet feeding accelerates JH2O2 and impairs insulin sensitivity (2). The fact that a ∼50% reduction of JH2O2 in sod2Tg or mcatTg mice was associated with enhanced exercise-mediated MGU whereas a more complete reduction of mtH2O2 in mtAO mice fully abolished this effect, suggests that the metabolic surplus of excess dietary fat intake shifts control of MGU by mtROS so that a critical mtROS level is necessary for augmentation of MGU during exercise. This suggests that a critical mitochondrial oxidative status must be present for its role in cell signaling (45, 58).

Insulin resistance and obesity impairs AMPK activation during exercise in skeletal muscle (30, 53). Exercise-induced AMPK activation was absent in HF-fed WT mice, but restored in HF-fed sod2Tg and mcatTg mice to levels in chow-fed WT mice. In contrast, AMPK activity was unaffected in HF-fed mtAO mice. This coincided with the lack of an enhanced Kg in HF-fed mtAO mice. These data show that restoration of the exercise-induced increase in AMPK signaling associates with enhanced exercise-mediated Kg in insulin-resistant mice. Whether there is a causal linkage remains to be defined. The role of mtROS on regulating AMPK activation has not yet been demonstrated. One possibility is that increased mtROS production associated with HF feeding could cause an oxidative modification of the enzyme itself, therefore impairing its activation in response to exercise. It is also possible that increased mtROS associated with HF feeding decreases the upstream kinase of AMPK. Studies have shown that obese insulin-resistant rodents have decreased LKB1-AMPK-PGC-1α pathway (54). PGC-1α is an AMPK-regulated transcription factor that regulates mitochondria biogenesis (25). All these data suggest that mtROS production is associated with the regulation of AMPK activation in the HF condition. However, the effects of AMPK activation are diverse, and increased mtROS scavenging could conceivably act on a range of pathways when it restores AMPK activation. Furthermore, increased exercise Kg in HF-fed sod2Tg and mcatTg mice was not associated with alterations in the expression of GLUT4 or HKII. The contribution of HKII compartmentation and spatial barriers under these conditions remains to be studied.

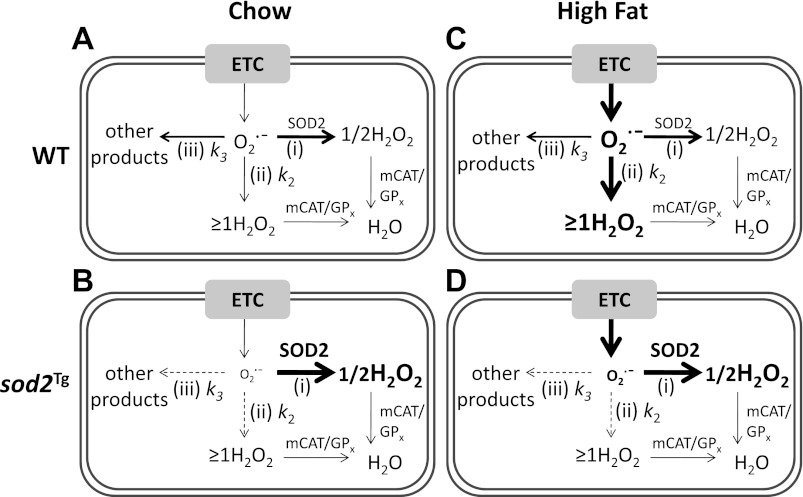

Nutritional State Determines the Route of O2˙− Removal

Effects of increased SOD expression on production of H2O2 are controversial (11, 42, 47, 49, 55, 62). Different paradigms and mathematical models have been used to explain inconsistencies (8, 9, 19, 32). The reason for these seemingly paradoxical findings is that H2O2 production depends on the balance of various processes that react with O2˙− (Fig. 6). These are the 1) dismutation reaction catalyzed by SOD, which produces one-half molecule of H2O2 per molecule of O2˙−; 2) reactions that consume O2˙− to produce one or more molecules of H2O2 (e.g., reactions with [4Fe-4S]-containing dehydratases, hydroquinols, and thiols); and 3) reactions that consume O2˙− without producing H2O2 (e.g., reactions with nitric oxide, ubiquinone, and cytochrome c3+). The finding that chow-fed sod2Tg mice have either increased or unchanged JH2O2 suggests that the rate of O2˙− removal in WT mice through reaction 3 (no H2O2 formation) equals to or exceeds the rate of removal through reaction 2 (≥1 H2O2 formation). Therefore, when SOD2 is overexpressed and the reactions for O2˙− removal are shifted to reaction 1 from reactions 2 and 3, the net balance of H2O2 will be either increased or remain the same. This is because the decrease in H2O2 produced from reactions 2 and 3 is less than or equal to the increase in H2O2 produced by reaction 1. Our results are consistent with the mathematic model of Gardner et al. (19). Gardner et al. (19) analyzed a minimal mathematic model where O2˙− dismutation by SOD is treated as pseudo-first-order processes, and both O2˙− production and the activity of enzymes other than SOD are considered constant. They concluded that at steady state when O2˙− production equals the rate of O2˙− consumption, the overall rate of H2O2 production is dependent on the rate constants of reactions 2 and 3. When rate constant for reaction 2 (k2) is less than rate constant for reaction 3 (k3), H2O2 production increases when SOD concentration increases. When k2 = k3, H2O2 production stays constant when SOD concentration increases. When k2 > k3, H2O2 goes down when SOD concentration increases (see Ref. 19 for detailed model). Therefore, our data support the existing mathematic model for this complex system.

Fig. 6.

Proposed models for how SOD2 overexpression influences mitochondrial H2O2 production in muscle of sedentary chow- and HF-fed mice. A: superoxide anion (O2˙−), predominantly generated from complex I and III of the electron transport chain (ETC) in mitochondria is removed by 3 processes: 1) reaction catalyzed by SOD2 that produces one half of H2O2 per O2˙− molecule consumed; 2) reactions that produce one or more H2O2 per O2˙−; and 3) reactions that do not produce any H2O2 molecules. H2O2 is then broken down to H2O and O2 by antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase targeted to mitochondria (mCAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). A thicker line represents a greater reactivity. k2 and k3 are rate constants for reactions 2 and 3. B: as SOD2 concentration increases, the steady-state concentration of O2˙− decreases and the flux of O2˙− consumption shifts from reactions 2 and 3 to reaction 1. Dashed lines represent reduced reactions and bold lines represent increased reactions. C: on a HF diet, both steady-state levels of O2˙− and H2O2 are increased. We propose that O2˙− removal is reliant on reaction 2 in HF-fed WT mice. Enlarged fonts represent increased concentrations and reduced fonts represent decreased concentrations. D: in HF-fed sod2Tg mice, mitochondrial H2O2 production is reduced compared with HF-fed WT mice, attributable to the shift from reaction 2 that produces one or more H2O2 to reaction 1 that produces only one-half of H2O2 per molecule of O2˙−.

SOD2 activity is normally sufficient to capture >90% of the O2˙− generated in mitochondria attributable to its high activity and abundance, relative to other O2˙− removal processes (32). Hence JH2O2 is only increased by ∼40% in sod2Tg mice that have a ∼300% increase in SOD2 activity (Fig. 2A). The balance of reactions described in Fig. 6 undergoes a transition with a HF diet. In contrast to an increased or constant JH2O2 evident in muscle of chow-fed sod2Tg mice, sod2Tg mice have decreased muscle JH2O2 in HF-fed mice. This reflects a transition so that, compared with chow-fed mice, HF-fed mice consume more mtO2˙− by the reactions that comprise 2 rather than those reactions that comprise 3 (Fig. 6). Furthermore, these data suggest that the main routes of mtO2˙− removal shift with HF feeding from reaction 1 to the reactions that comprise 2. This is supported by the fact that HF diet feeding causes a net increase in JH2O2 (2) with a potential decrease in SOD2 gene expression (52). One could speculate that a redox shift in sod2Tg mice alters the susceptibility of complexes I and III to a HF diet so that excessive oxidation of these complexes could repress their ability to generate mtO2˙−. This is unlikely because V̇o2 in HF-fed sod2Tg mice was not impaired compared with HF-fed WT mice.

Mitochondria as a Source of ROS During Exercise

It has long been assumed that ROS formation by working muscle is a by-product of increased mitochondrial oxygen consumption (10). Recent work, however, showed that mitochondria are not the major source of ROS during contraction in isolated muscle (38). The mitochondrial ROS production rate is apparently lower than original estimates, and the increase in intracellular ROS is less than the increase in extracellular ROS during exercise (26). Results from the present study, however, show that in the whole organism the mitochondrial oxidative status is critical, as an increase in the antioxidant capacity specifically targeted to mitochondria enhanced MGU during exercise. It is impossible to directly measure the predominant organelle responsible for the increase in ROS in vivo. The approach we used is advantageous in that it does not rely on direct measurements, but rather on functional outcomes of genetic manipulations of mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes. This paper shows a functional role for high chronic mitochondrial antioxidant scavenging capacity in MGU during exercise, despite the probability that extramitochondrial scavenging capacity is unaffected.

Summary

These data show for the first time that a genetic increase in mitochondrial antioxidative capacity increases an index of exercise-stimulated MGU in vivo in mice fed chow or a HF diet that accelerates ROS formation. These results link mitochondrial function to the exercise-induced increase in glucose metabolism. The present studies also emphasize that the regulation of mtROS on MGU is dependent on metabolic state because HF-fed mice are uniquely affected by muscle mitochondrial antioxidative capacity. It is noteworthy that an increase in mitochondrial antioxidative capacity alone reduces nitrotyrosine accumulation by 25–50% regardless of diet, supporting the concept that in vivo the mitochondria are important determinants of total muscle oxidative status. The present studies shed new light on the important role of mitochondrial antioxidative capacity in the physiological response to exercise in healthy and metabolic disease states.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-073488 (to P. D. Neufer), DK-054902 (to D. H. Wasserman), and DK-059637 (Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center; to D. H. Wasserman).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.K., P.D.N., and D.H.W. conception and design of research; L.K., M.E.L., J.S.B., R.S.L.-Y., W.H.M., F.D.J., C.-T.L., C.G.P., and E.J.A. performed experiments; L.K., J.S.B., R.S.L.-Y., C.-T.L., and C.G.P. analyzed data; L.K., J.S.B., R.S.L.-Y., C.-T.L., C.G.P., P.D.N., and D.H.W. interpreted results of experiments; L.K. and C.-T.L. prepared figures; L.K. drafted manuscript; L.K., C.G.P., P.D.N., and D.H.W. edited and revised manuscript; L.K., J.S.B., C.G.P., P.D.N., and D.H.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Melissa B. Downing and Lillian B. Nanney of the Immunohistochemistry Core Laboratory of the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdul-Ghani MA, DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010: 476279, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin CT, Price JW, 3rd, Kang L, Rabinovitch PS, Szeto HH, Houmard JA, Cortright RN, Wasserman DH, Neufer PD. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 119: 573–581, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asha Devi S, Prathima S, Subramanyam MV. Dietary vitamin E and physical exercise: I. Altered endurance capacity and plasma lipid profile in ageing rats. Exp. Gerontol 38: 285–290, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ayala JE, Bracy DP, Julien BM, Rottman JN, Fueger PT, Wasserman DH. Chronic treatment with sildenafil improves energy balance and insulin action in high fat-fed conscious mice. Diabetes 56: 1025–1033, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ayala JE, Bracy DP, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. Considerations in the design of hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in the conscious mouse. Diabetes 55: 390–397, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berglund ED, Li CY, Poffenberger G, Ayala JE, Fueger PT, Willis SE, Jewell MM, Powers AC, Wasserman DH. Glucose metabolism in vivo in four commonly used inbred mouse strains. Diabetes 57: 1790–1799, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Booth FW, Laye MJ. Lack of adequate appreciation of physical exercise's complexities can pre-empt appropriate design and interpretation in scientific discovery. J Physiol 587: 5527–5539, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buerk DG, Lamkin-Kennard K, Jaron D. Modeling the influence of superoxide dismutase on superoxide and nitric oxide interactions, including reversible inhibition of oxygen consumption. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 1488–1503, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buettner GR, Ng CF, Wang M, Rodgers VG, Schafer FQ. A new paradigm: manganese superoxide dismutase influences the production of H2O2 in cells and thereby their biological state. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 1338–1350, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davies KJ, Quintanilha AT, Brooks GA, Packer L. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 107: 1198–1205, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Haan JB, Cristiano F, Iannello R, Bladier C, Kelner MJ, Kola I. Elevation in the ratio of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase to glutathione peroxidase activity induces features of cellular senescence and this effect is mediated by hydrogen peroxide. Hum Mol Genet 5: 283–292, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fueger PT, Bracy DP, Malabanan CM, Pencek RR, Granner DK, Wasserman DH. Hexokinase II overexpression improves exercise-stimulated but not insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake in high-fat-fed C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes 53: 306–314, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fueger PT, Bracy DP, Malabanan CM, Pencek RR, Wasserman DH. Distributed control of glucose uptake by working muscles of conscious mice: roles of transport and phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 286: E77–E84, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fueger PT, Hess HS, Posey KA, Bracy DP, Pencek RR, Charron MJ, Wasserman DH. Control of exercise-stimulated muscle glucose uptake by GLUT4 is dependent on glucose phosphorylation capacity in the conscious mouse. J Biol Chem 279: 50956–50961, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fueger PT, Lee-Young RS, Shearer J, Bracy DP, Heikkinen S, Laakso M, Rottman JN, Wasserman DH. Phosphorylation barriers to skeletal and cardiac muscle glucose uptakes in high-fat fed mice: studies in mice with a 50% reduction of hexokinase II. Diabetes 56: 2476–2484, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fueger PT, Li CY, Ayala JE, Shearer J, Bracy DP, Charron MJ, Rottman JN, Wasserman DH. Glucose kinetics and exercise tolerance in mice lacking the GLUT4 glucose transporter. J Physiol 582: 801–812, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fueger PT, Shearer J, Krueger TM, Posey KA, Bracy DP, Heikkinen S, Laakso M, Rottman JN, Wasserman DH. Hexokinase II protein content is a determinant of exercise endurance capacity in the mouse. J Physiol 566: 533–541, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujii N, Jessen N, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase and the regulation of glucose transport. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E867–E877, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gardner R, Salvador A, Moradas-Ferreira P. Why does SOD overexpression sometimes enhance, sometimes decrease, hydrogen peroxide production? A minimalist explanation. Free Radic Biol Med 32: 1351–1357, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gomez-Cabrera MC, Borras C, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Ji LL, Vina J. Decreasing xanthine oxidase-mediated oxidative stress prevents useful cellular adaptations to exercise in rats. J Physiol 567: 113–120, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gomez-Cabrera MC, Domenech E, Romagnoli M, Arduini A, Borras C, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Vina J. Oral administration of vitamin C decreases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and hampers training-induced adaptations in endurance performance. Am J Clin Nutr 87: 142–149, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Halseth AE, Bracy DP, Wasserman DH. Limitations to exercise- and maximal insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake. J Appl Physiol 85: 2305–2313, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higashida K, Kim SH, Higuchi M, Holloszy JO, Han DH. Normal adaptations to exercise despite protection against oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301: E779–E784, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoehn KL, Salmon AB, Hohnen-Behrens C, Turner N, Hoy AJ, Maghzal GJ, Stocker R, Van Remmen H, Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ, Richardson AR, James DE. Insulin resistance is a cellular antioxidant defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17787–17792, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hood DA, Irrcher I, Ljubicic V, Joseph AM. Coordination of metabolic plasticity in skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 209: 2265–2275, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jackson MJ. Control of reactive oxygen species production in contracting skeletal muscle. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 2477–2486, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones DP. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C849–C868, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kang L, Ayala JE, Lee-Young RS, Zhang Z, James FD, Neufer PD, Pozzi A, Zutter MM, Wasserman DH. Diet-induced muscle insulin resistance is associated with extracellular matrix remodeling and interaction with integrin alpha2beta1 in mice. Diabetes 60: 416–426, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katz A, Sahlin K, Broberg S. Regulation of glucose utilization in human skeletal muscle during moderate dynamic exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 260: E411–E415, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee-Young RS, Ayala JE, Fueger PT, Mayes WH, Kang L, Wasserman DH. Obesity impairs skeletal muscle AMPK signaling during exercise: role of AMPKalpha2 in the regulation of exercise capacity in vivo. Int J Obes (Lond) 35: 982–989, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee-Young RS, Griffee SR, Lynes SE, Bracy DP, Ayala JE, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. Skeletal muscle AMP-activated protein kinase is essential for the metabolic response to exercise in vivo. J Biol Chem 284: 23925–23934, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liochev SI, Fridovich I. The effects of superoxide dismutase on H2O2 formation. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 1465–1469, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lowry OH, Passonneau JV. A flexible system of enzymatic analysis. Starch 25: 322, 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Merry TL, Dywer RM, Bradley EA, Rattigan S, McConell GK. Local hindlimb antioxidant infusion does not affect muscle glucose uptake during in situ contractions in rat. J Appl Physiol 108: 1275–1283, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Merry TL, McConell GK. Do reactive oxygen species regulate skeletal muscle glucose uptake during contraction? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 40: 102–105, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Merry TL, Steinberg GR, Lynch GS, McConell GK. Skeletal muscle glucose uptake during contraction is regulated by nitric oxide and ROS independently of AMPK. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E577–E585, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Merry TL, Wadley GD, Stathis CG, Garnham AP, Rattigan S, Hargreaves M, McConell GK. N-acetylcysteine infusion does not affect glucose disposal during prolonged moderate-intensity exercise in humans. J Physiol 588: 1623–1634, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Michaelson LP, Shi G, Ward CW, Rodney GG. Mitochondrial redox potential during contraction in single intact muscle fibers. Muscle Nerve 42: 522–529, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Motoori S, Majima HJ, Ebara M, Kato H, Hirai F, Kakinuma S, Yamaguchi C, Ozawa T, Nagano T, Tsujii H, Saisho H. Overexpression of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase protects against radiation-induced cell death in the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HLE. Cancer Res 61: 5382–5388, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murrant CL, Reid MB. Detection of reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species in skeletal muscle. Microsc Res Tech 55: 236–248, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raineri I, Carlson EJ, Gacayan R, Carra S, Oberley TD, Huang TT, Epstein CJ. Strain-dependent high-level expression of a transgene for manganese superoxide dismutase is associated with growth retardation and decreased fertility. Free Radic Biol Med 31: 1018–1030, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ranganathan AC, Nelson KK, Rodriguez AM, Kim KH, Tower GB, Rutter JL, Brinckerhoff CE, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Jeffrey JJ, Melendez JA. Manganese superoxide dismutase signals matrix metalloproteinase expression via H2O2-dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem 276: 14264–14270, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Richter EA, Jensen P, Kiens B, Kristiansen S. Sarcolemmal glucose transport and GLUT-4 translocation during exercise are diminished by endurance training. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E89–E95, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Richter EA, Ruderman NB. AMPK and the biochemistry of exercise: implications for human health and disease. Biochem J 418: 261–275, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rigoulet M, Yoboue ED, Devin A. Mitochondrial ROS generation and its regulation: mechanisms involved in H(2)O(2) signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 459–468, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ristow M, Zarse K, Oberbach A, Kloting N, Birringer M, Kiehntopf M, Stumvoll M, Kahn CR, Bluher M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 8665–8670, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodriguez AM, Carrico PM, Mazurkiewicz JE, Melendez JA. Mitochondrial or cytosolic catalase reverses the MnSOD-dependent inhibition of proliferation by enhancing respiratory chain activity, net ATP production, and decreasing the steady state levels of H(2)O(2). Free Radic Biol Med 29: 801–813, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sandstrom ME, Zhang SJ, Bruton J, Silva JP, Reid MB, Westerblad H, Katz A. Role of reactive oxygen species in contraction-mediated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol 575: 251–262, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schmidt KN, Amstad P, Cerutti P, Baeuerle PA. The roles of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide as messengers in the activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B. Chem Biol 2: 13–22, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, Treuting P, Ogburn CE, Emond M, Coskun PE, Ladiges W, Wolf N, Van Remmen H, Wallace DC, Rabinovitch PS. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science 308: 1909–1911, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Silva JP, Shabalina IG, Dufour E, Petrovic N, Backlund EC, Hultenby K, Wibom R, Nedergaard J, Cannon B, Larsson NG. SOD2 overexpression: enhanced mitochondrial tolerance but absence of effect on UCP activity. EMBO J 24: 4061–4070, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sreekumar R, Unnikrishnan J, Fu A, Nygren J, Short KR, Schimke J, Barazzoni R, Nair KS. Impact of high-fat diet and antioxidant supplement on mitochondrial functions and gene transcripts in rat muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E1055–E1061, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sriwijitkamol A, Coletta DK, Wajcberg E, Balbontin GB, Reyna SM, Barrientes J, Eagan PA, Jenkinson CP, Cersosimo E, DeFronzo RA, Sakamoto K, Musi N. Effect of acute exercise on AMPK signaling in skeletal muscle of subjects with type 2 diabetes: a time-course and dose-response study. Diabetes 56: 836–848, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sriwijitkamol A, Ivy JL, Christ-Roberts C, DeFronzo RA, Mandarino LJ, Musi N. LKB1-AMPK signaling in muscle from obese insulin-resistant Zucker rats and effects of training. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E925–E932, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Teixeira HD, Schumacher RI, Meneghini R. Lower intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels in cells overexpressing CuZn-superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7872–7875, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tiidus PM, Houston ME. Antioxidant and oxidative enzyme adaptations to vitamin E deprivation and training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26: 354–359, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toyoda T, Hayashi T, Miyamoto L, Yonemitsu S, Nakano M, Tanaka S, Ebihara K, Masuzaki H, Hosoda K, Inoue G, Otaka A, Sato K, Fushiki T, Nakao K. Possible involvement of the alpha1 isoform of 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase in oxidative stress-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E166–E173, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling. Mol Cell 26: 1–14, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wadley GD, Lee-Young RS, Canny BJ, Wasuntarawat C, Chen ZP, Hargreaves M, Kemp BE, McConell GK. Effect of exercise intensity and hypoxia on skeletal muscle AMPK signaling and substrate metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E694–E702, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wasserman DH. Four grams of glucose. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E11–E21, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wasserman DH, Kang L, Ayala JE, Fueger PT, Lee-Young RS. The physiological regulation of glucose flux into muscle in vivo. J Exp Biol 214: 254–262, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wenk J, Brenneisen P, Wlaschek M, Poswig A, Briviba K, Oberley TD, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Stable overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase in mitochondria identifies hydrogen peroxide as a major oxidant in the AP-1-mediated induction of matrix-degrading metalloprotease-1. J Biol Chem 274: 25869–25876, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Winder WW, Taylor EB, Thomson DM. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the molecular adaptation to endurance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38: 1945–1949, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yfanti C, Akerstrom T, Nielsen S, Nielsen AR, Mounier R, Mortensen OH, Lykkesfeldt J, Rose AJ, Fischer CP, Pedersen BK. Antioxidant supplementation does not alter endurance training adaptation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42: 1388–1395, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]