Abstract

The transcriptional repressor Capicua (Cic) controls multiple aspects of Drosophila embryogenesis and has been implicated in vertebrate development and human diseases. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) can antagonize Cic-dependent gene repression, but the mechanisms responsible for this effect are not fully understood. Based on genetic and imaging studies in the early Drosophila embryo, we found that Torso RTK signaling can increase the rate of Cic degradation by changing its subcellular localization. We propose that Cic is degraded predominantly in the cytoplasm and show that Torso reduces the stability of Cic by controlling the rates of its nucleocytoplasmic transport. This model accounts for the experimentally observed spatiotemporal dynamics of Cic in the early embryo and might explain RTK-dependent control of Cic in other developmental contexts.

Keywords: RTK, Repressor, Signaling, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

The HMG box transcriptional repressor Capicua (Cic) regulates multiple stages of Drosophila development (reviewed by Jiménez et al., 2012). In vertebrates, Cic is expressed in the developing cerebellum and controls matrix metalloproteases in the developing lung (Lee et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2011). Cic has been implicated in human diseases, including several cancers (Kawamura-Saito et al., 2006; Lam et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2008; Bettegowda et al., 2011).

During Drosophila development, genes with Cic-binding sites are expressed in cells with activated RTKs (Roch et al., 2002; Löhr et al., 2009; Ajuria et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011a). Studies with cultured human cells and in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia demonstrated that RTKs also counteract gene repression by Cic in vertebrates (Dissanayake et al., 2011; Fryer et al., 2011), but the mechanisms responsible for this effect are still poorly understood. Here, we investigate the RTK-dependent control of Cic in the early Drosophila embryo, the system where Cic was originally identified (Jiménez et al., 2000). Our analysis of Cic dynamics in living embryos revealed that Torso RTK signaling reduces the stability of Cic. Furthermore, Torso reduces the rate of Cic nuclear import and increases its export rate. Our results can be explained by a model where degradation of Cic is a consequence of changes in the rates of its nucleocytoplasmic shuttling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenes and fly stocks

The Capicua-Dronpa and Capicua-Venus fusion constructs were generated by replacing the HA-tag of the cic-rescuing construct (Jiménez et al., 2000) with the fluorescent proteins Venus (Nagai et al., 2002) and Dronpa (Ando et al., 2004). Both constructs rescue sterility of cic1 females (Jiménez et al., 2000). The trk1 and torD4021 alleles have been described previously (Schüpbach and Wieschaus, 1989; Sprenger and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1992). Unfertilized eggs were generated by crossing cicD;cic1 virgins to sterile males Ms(2)M1 (Bloomington stock 2121). The HA-tagged constructs have been described previously (Astigarraga et al., 2007).

Immunostaining, qRT-PCR and western blot

The spatial distribution of dpERK was analyzed as described elsewhere (Coppey et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010). The anti-HA rat monoclonal antibody (Roche) was used in 1:100 for immunostaining and in 1:1000 for western blotting, which was carried out as described elsewhere (Drocco et al., 2011). To measure maternally deposited mRNA encoding HA-tagged cic, embryos were collected within 30 minutes after egg deposition. Based on qRT-PCR, mRNA of the mutant HMG construct is 2.65±0.3 more abundant than the mRNA of wild-type cic-HA.

Lifetime measurements and FRAP experiments

To measure Cic lifetime, we used a method based on photo-conversion of the Cic-Dronpa fusion protein, as described previously (Drocco et al., 2011). To measure lifetime in the middle of the embryo, fluorescence from 30-70% egg length was used; for lifetime at the poles, the first and last 10% egg length were used. FRAP experiments were carried out with cycle 13 embryos expressing the Cic-Venus construct. Venus was excited with 514 nm and emission was monitored between 525 and 600 nm. Recovery in the bleached nucleus was imaged every 16 seconds, at low levels of excitation light to avoid bleaching. Background levels were estimated from wild-type embryos that do not express Cic-Venus. Analysis of FRAP data is described in supplementary material Appendix S1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Dynamics of Cic in the early embryo

The initial requirement for Cic in Drosophila development involves Torso RTK signaling at the anterior and posterior poles of the egg (Jiménez et al., 2000). The embryo at this stage is a syncytium undergoing rounds of synchronous nuclear division. Locally activated Torso induces phosphorylation and activation of the Extracellular Signal Activated Kinase (ERK), which reduces Cic levels at both poles of the embryo (Furriols and Casanova, 2003).

To analyze Cic dynamics in live embryos, we generated transgenic flies expressing Cic fused to either the photo-switchable protein Dronpa (Ando et al., 2004) or the fluorescent protein Venus (Nagai et al., 2002) and controlled by the regulatory sequences of the cic gene (Fig. 1A). The spatial distributions of Cic resulting from either of these constructs mimic the distribution of endogenous Cic (supplementary material Fig. S1).

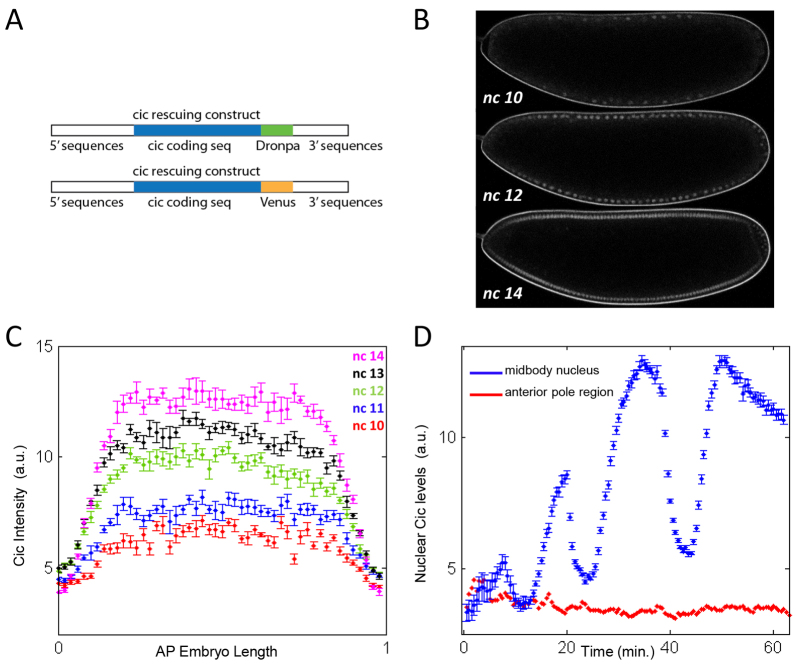

Fig. 1.

Dynamics of Cic in the early Drosophila embryo. (A) Schematics of the fusion constructs. Cic is fused to Dronpa or Venus and flanked by the endogenous 5′ and 3′ regulatory regions. Both constructs rescue sterility of females homozygous mutant for Cic. (B) Live imaging of Cic-Dronpa embryos at different nuclear division cycles. Cic levels are low at the poles and high in the mid-body of the embryo. (C) Quantified average intensity profiles of Cic along the AP axis from cycle 10 interphase (red) to ~15 minutes into cycle 14 interphase (magenta). Error bars correspond to s.e.m. based on five embryos. (D) Dynamics of the nuclear levels of Cic in the middle of the embryo (blue) and at the anterior pole (red) as a function of time; t=0 corresponds to nuclear cycle 10 mitosis. Error bars are s.e.m. for 50 nuclei within the mid-body of the same embryo.

Cic is first detected after the 9th nuclear division (Fig. 1B-D). At this stage, Cic predominantly localizes to nuclei and levels in the middle region of the embryo are already significantly higher than those at the poles. Levels of Cic in the central region drop during mitoses, reflecting protein dispersal into the cytoplasm. During the subsequent interphase, nuclear levels recover and eventually exceed those observed in the preceding mitosis. The levels within individual nuclei increase ~2.5-fold between cycles 10 and the beginning of cycle 14. By contrast, levels at the poles remain low from the first time Cic is detected and until the embryo reaches the cellularization stage.

Torso increases the rate of Cic degradation

Studies in mice suggest that Cic-target gene derepression depends on RTK-dependent reduction of Cic levels (Fryer et al., 2011). To explore this mechanism in the embryo, we examined the degradation rates of Cic at different levels of RTK signaling. Based on the pattern of double-phosphorylated ERK (dpERK), which serves as a reporter of Torso signaling, the central region and poles of the wild-type embryo correspond to zero and maximal levels of Torso activation, respectively. To generate an intermediate level of Torso activation, we used a gain-of-function allele of torso (Szabad et al., 1989) (Fig. 2A,B).

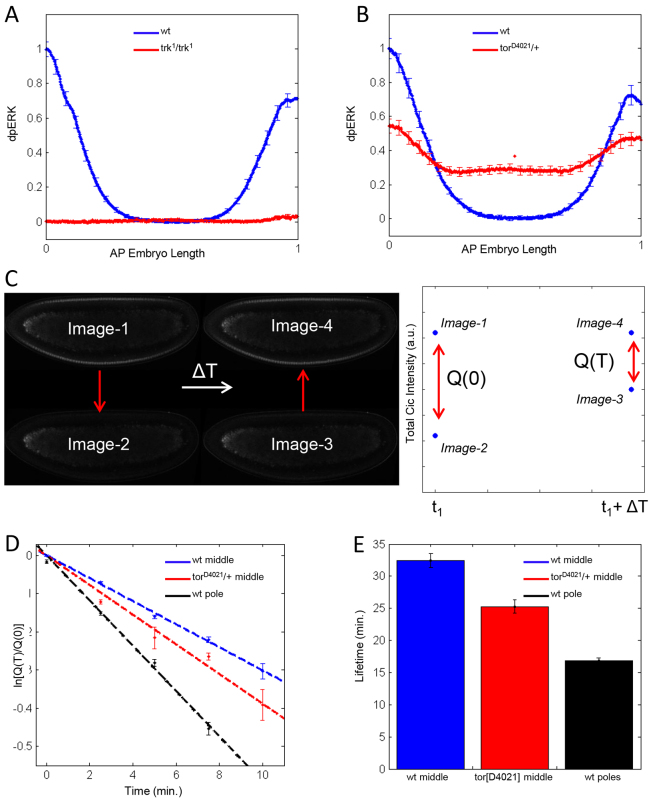

Fig. 2.

Cic lifetime is reduced by Torso signaling. (A) Quantified average dpERK gradients in the control (Histone GFP, blue) and the loss-of-function mutant trk1/trk1 (red) Drosophila embryos. The dpERK levels in the main body regions of the wild-type embryos are the same as in the trk1/trk1 embryos. Thus, the main body region of the wild-type embryos corresponds to zero level of Torso activation. Error bars correspond to s.e.m. Numbers of embryos used in the analysis: nwt=21 and ntrk1/trk1=17. (B) Quantified average dpERK gradients in the control (blue) and gain-of-function mutant torD4021/+ (red). The levels in the central region of mutant embryos are significantly increased. nwt=24 and ntorD4021=24. (C) Outline of the optical pulse labeling experiment. A population of Dronpa-tagged molecules is converted to the dark state at time t1. After a waiting time ΔT, the dark-converted population is converted back to the bright state. The fraction of surviving Cic-Dronpa, Q(T)/Q(0) is a measure of its lifetime. (D) First-order fits to survival kinetics of Cic-Dronpa in the middle of wild-type embryos (blue), in the middle of torD4021/+ embryos (red) and in the pole region of wild-type embryos (black). Error bars are s.e.m., based on a minimum of 40 samples for each waiting time. (E) Cic lifetimes at three different levels of RTK activation. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

If Torso reduces the stability of Cic, its lifetime should be inversely correlated with the level of ERK activation. To test this prediction, we measured the lifetime of Cic using an optical pulse-labeling method, which relies on the photo-switchable fluorescent protein Dronpa. Dronpa is synthesized in a bright state, which can be reversibly converted to the dark state by brief illumination at 496 nm. The dark state is optically stable, but it can be converted back to the bright state by a pulse at 405 nm wavelength. This can be used to label a population of Cic molecules (Fig. 2C). As the dark population is unaffected by the newly synthesized/matured protein, its dynamics reflects only degradation and can be used to estimate the lifetime of Cic (the inverse of the first order degradation rate constant).

Fig. 2D shows the time courses of the surviving fractions of labeled Cic at three different levels of Torso activation. Fitting these curves to a first-order degradation model, we found that at zero level of Torso activation Cic is degraded with a characteristic lifetime of ~30 minutes. At the poles, the lifetime is reduced to ~15 minutes. At an intermediate level of Torso signaling, the lifetime of Cic has a value of ~25 minutes. Thus, the lifetime of Cic is inversely correlated with the level of Torso signaling (Fig. 2E).

Torso controls nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Cic

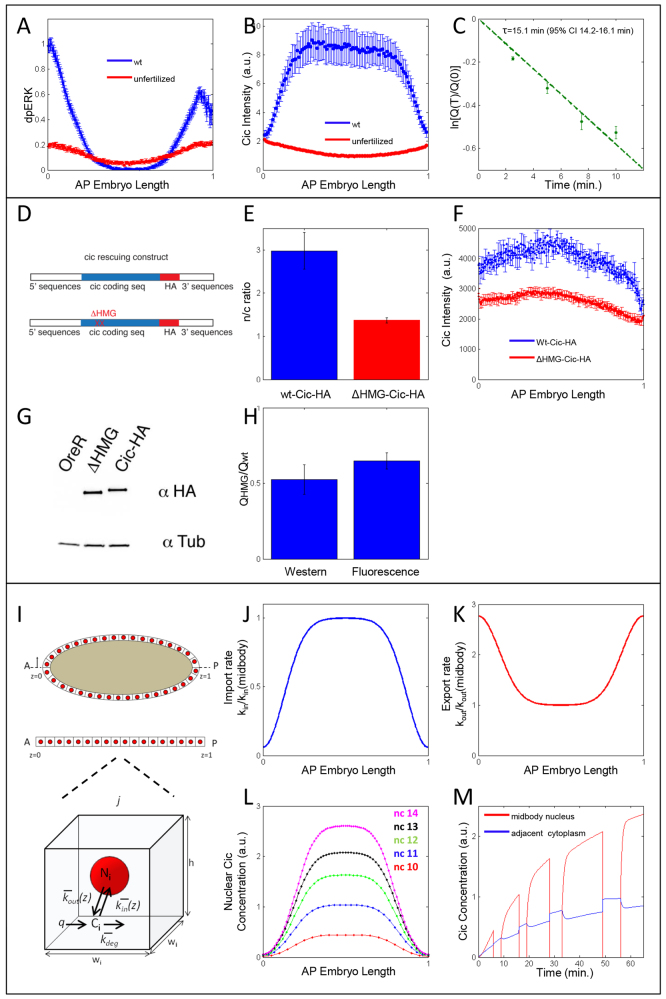

In the central region of wild-type embryos, Cic is predominantly nuclear, with a nucleocytoplasmic ratio of ~9. When the levels of Torso activation are increased, this ratio is reduced to ~3, suggesting that Torso affects the rates of Cic nuclear import and/or export. To quantify these rates, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) (Axelrod et al., 1976).

After nuclear bleaching, nuclear levels of Cic recover only a fraction of their pre-bleached value before the next mitosis (Fig. 3A). We limited our analysis of FRAP kinetics to the first 4 minutes after bleaching, which is considerably less than the time scale of Cic degradation. This allows us to neglect degradation in the analysis of FRAP kinetics. During this time, Cic levels in the cytoplasm remain constant (Fig. 3B). Under these conditions, FRAP can be analyzed using a model in which changes in the nuclear levels reflect export from the nucleus and import from the cytoplasm with constant concentration. Based on this model, we estimated the rate constants of import and export at two different levels of Torso signaling (Fig. 3C,D). Both of these constants are affected by increased Torso signaling associated with the torso gain-of-function allele: the import rate constant is reduced and the export rate is increased. These effects lower the nuclear residency time of Cic and increase the time spent in the cytoplasm. Thus, Torso controls nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Cic.

Fig. 3.

Torso controls nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Cic. (A) Representative FRAP data of a single bleached nucleus taken at the surface of a wild-type Drosophila embryo during early nuclear cycle 13. Quantified average intensities for the bleached nucleus (blue), immediately adjacent cytoplasm (red), a nearby nucleus (black) and cytoplasm remote from the bleached nucleus (purple). (B) Average recovery profiles of 17 bleached nuclei in the mid-body region of embryos with the torso gain-of-function allele. Error bars in B-D correspond to s.e.m. (C) Import rate constant decreases with increasing RTK signaling levels (P=0.015, based on a two-tailed t-test comparison of the means; nWT=16, ntorD4021=17). (D) Export rate constant increases with increasing RTK signaling levels (P=0.05, based on a two-tailed t-test comparison of the means; nWT=16, ntorD4021=17). Data are mean±s.e.m. in C,D.

Nuclei protect Cic from degradation in the cytoplasm

The effects of Torso on Cic lifetime and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling need not be independent from each other: the observed decrease of Cic lifetime might be a consequence of the sizes of the nuclear and cytoplasmic pools. If Cic were degraded only in the cytoplasm, then nuclei would ‘protect’ Cic from degradation. In this case, the effect of Torso on Cic degradation would reflect the relative times spent by Cic molecules in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments.

This model predicts that the lifetime of Cic could be reduced even in the absence of Torso signaling, if its nuclear import is prevented. As a test of this model, we used the fact that Drosophila eggs can be activated without fertilization. Such eggs are blocked at the completion of meiosis and do not undergo nuclear replication, but do initiate activation processes leading to translation of maternal RNAs and establish maternal gradients of positional information (Horner and Wolfner, 2008). As Cic and components of the Torso pathway are maternally supplied, it is possible to characterize their distributions in unfertilized eggs.

In the central region of unfertilized eggs, dpERK levels remain close to the background level observed in embryos (Fig. 4A; Fig. 2A-C). In the wild-type embryo, these low levels are associated with maximal Cic lifetime. If Torso affects Cic lifetime through its effect on nuclear shuttling, then low levels of dpERK should no longer be associated with high levels of Cic, as the protein is entirely cytoplasmic in unfertilized eggs. Indeed, we found that the spatial pattern of Cic in unfertilized eggs is uniform. Moreover, the levels are significantly reduced, compared with the levels in the central region of wild-type embryos (Fig. 4B).

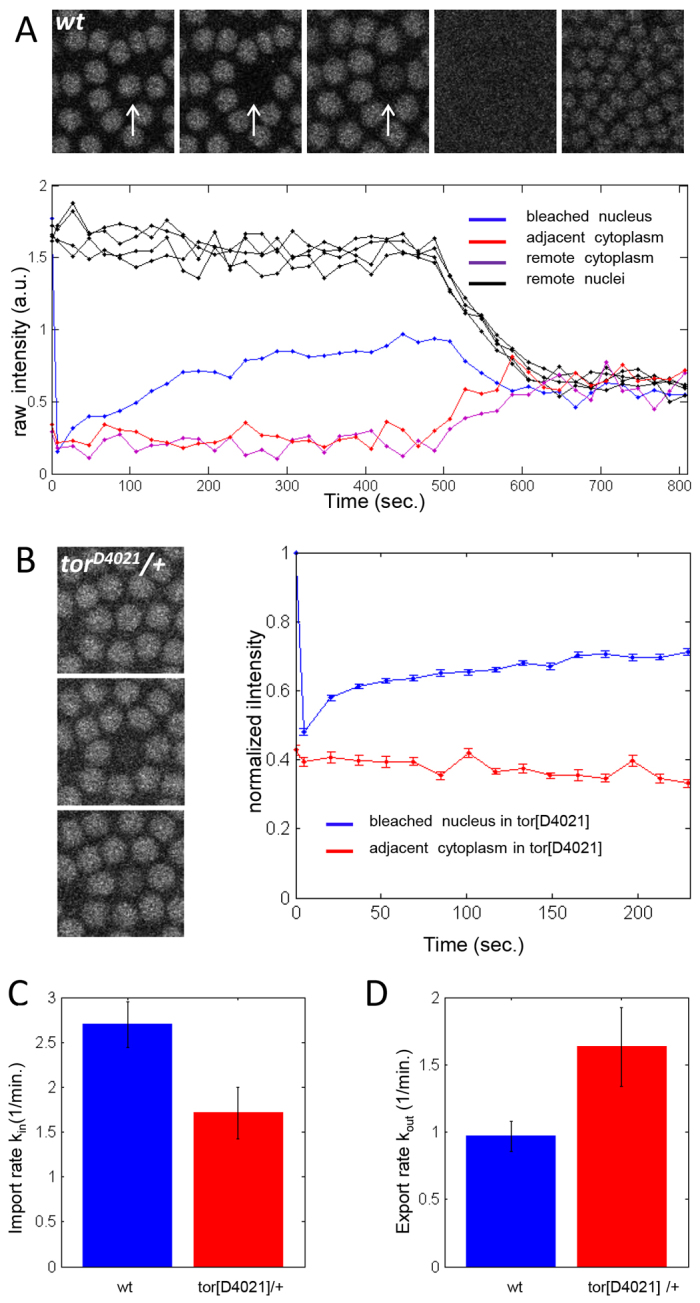

Fig. 4.

Nuclei protect Cic from degradation. (A) Quantified dpERK gradient in wild-type Drosophila embryos (blue) and unfertilized eggs (red). Unfertilized eggs and control embryos were fixed and stained together. Error bars correspond to s.e.m. nWT=21, nunfertilized=37. (B) Quantified average Cic gradient in wild-type and unfertilized embryos expressing Cic-Dronpa. Wild-type embryos were imaged ~20 minutes into cycle 14. Unfertilized eggs were imaged ~2 hours after egg deposition. No significant changes of Cic levels were observed during this time. Error bars at a given position correspond to s.e.m., nWT=10, nunfertilized=80. (C) Survival kinetics of Cic-Dronpa in unfertilized eggs. Error bars correspond to s.e.m. First-order fit results in an average protein lifetime of ~15 minutes (mean=15.1, 95% confidence interval 14.2-16.1 minutes). (D) Schematics of the wild-type and HMG-box-deleted HA-tagged Cic constructs. (E) Nucleocytoplasmic ratios of the wild-type and mutant Cic constructs (n=3). (F) Intensity profiles of the wild-type (blue) and mutant (red) Cic proteins, after correcting for the differential amount of maternally deposited mRNA. The curves are averages based on 16 (wild-type) and 12 (mutant) embryos. Error bars are s.e.m. (G) Western blot detecting HA-tagged Cic. (H) Relative amounts of Cic in embryos expressing either the wild-type or mutant versions of the HA-tagged Cic. The left bar corresponds to the western blot data from the whole-embryo extract (n=8, error bar indicates s.e.m.). The right bar corresponds to the immunofluorescence data, quantified in the mid-body of the embryo [30-70% egg length, n=16 (wild type) and 12 (mutant), error bar indicates s.e.m.]. In both cases, after correcting for the differential amounts of mRNA, the levels of the mutant protein is ~50% of the wild-type levels. (I) Schematic of the model of the embryo in which degradation takes place solely in the cytoplasm. Synthesis and degradation are assumed to remain constant throughout the AP axis, whereas import and export rates change spatially according to measured dpERK profiles (for more details, see supplementary material Appendix S1). (J,K) Spatial distribution of nuclear import (J) and export (K) rates along the AP axis used in the model. Rates are normalized with respect to the measured values measured in the mid-body of wild-type embryos. (L) Model results for the nuclear Cic gradient for nuclear cycles 10 (red) to 14 (magenta). (M) Model results for the levels of Cic in the nucleus (red) and in adjacent cytoplasmic island (blue) located at the center of the AP axis during nuclear cycles 10-14.

To test whether this reduction is due to changes in protein lifetime rather than a reduced synthesis rate in unfertilized eggs, we used the Cic-Dronpa construct to measure Cic lifetime in unfertilized eggs. The lifetime in the absence of nuclei is reduced to a value that is close to the value measured at the termini of wild-type embryos (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results support the model whereby Torso controls Cic degradation by changing its subcellular localization.

Experiments in unfertilized eggs test the model by changing the medium in which Cic is accumulated. Alternatively, one can keep the medium constant but impair nuclear localization of Cic. Although Cic does not have a canonical nuclear localization signal (NLS), it is known that other HMG box proteins contain a functional NLS within their HMG domains (Qin et al., 2003; Stros et al., 2007; Malki et al., 2010). A previous study established that deletion of the Cic HMG box not only abolishes its repressor activity but impairs nuclear localization (Astigarraga et al., 2007).

To determine whether altered nuclear localization affects protein levels, we compared Cic levels and nucleocytoplasmic ratio in a transgenic line expressing Cic without the HMG box to that in a line expressing a similarly tagged wild-type protein (Fig. 4D,E). Because RNA levels in transgenic lines vary depending on insertion site, we corrected apparent Cic levels by the mRNA levels in each line (see Materials and methods). After this correction, we found that levels of the mutant Cic protein were ~50% of the levels of the wild-type protein (Fig. 4F,G). A similar reduction was observed by quantitative western blot with whole embryo extracts (Fig. 4G). These results provide further support for the model whereby Cic is degraded mainly in the cytoplasm.

Model for Cic degradation

The mechanism whereby Cic stability is controlled by subcellular localization sheds light on the formation of the Cic gradient during the terminal patterning of the embryo. We propose that low levels of Cic at the poles can be explained by a model in which Cic is synthesized in a spatially uniform pattern, but is degraded nonuniformly in space, reflecting the effect of Torso on the rates of Cic nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. To illustrate this mechanism, we developed a computational model of Cic dynamics in the early embryo (Fig. 4I; supplementary material Appendix S1).

Based on the earlier models for the Bicoid and Dorsal gradients (Kanodia et al., 2009; Kavousanakis et al., 2010), the model assumes that Cic is synthesized at a constant rate and degraded only in the cytoplasm, following first-order kinetics with a spatially uniform rate constant. The effects of Torso are modeled by the spatially non-uniform rates of nuclear import and export (Fig. 4J,K), which we assumed to be linearly correlated with the experimentally observed levels of dpERK. When provided with measured rates of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and degradation, the model correctly predicts that the dynamic pattern of nuclear Cic remains low at the poles and increases in the mid-body during each nuclear cycle, a pattern consistent with our experimental data (Fig. 1; Fig. 4L,M).

According to this model, levels of Cic at the poles are downregulated because Cic molecules spend more time in the cytoplasm. This mechanism clearly works when nuclear Cic can rapidly exchange with cytoplasmic Cic, but we expect that it will also work when, as suggested by our FRAP results, only a fraction of Cic can exchange with the cytoplasm and is thus subject to degradation only during interphase. Even in this case, the entire population of Cic molecules would be released into the cytoplasm during mitosis. During the next interphase, nuclear residency of Cic at the poles would be lower than in the middle of the embryo and, hence, the protective effect of the nuclei would be reduced.

Conclusions

RTK signaling antagonizes transcriptional repression by Cic at multiple stages of Drosophila development (Jiménez et al., 2000; Roch et al., 2002; Astigarraga et al., 2007; Ajuria et al., 2011), in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia (Fryer et al., 2011) and in experiments with cultured mammalian cells (Dissanayake et al., 2011). We demonstrate that Cic lifetime is reduced in response to Torso RTK signaling in the Drosophila embryo. This effect results from the reduction of time spent by Cic molecules in nuclei, where Cic is protected from degradation. As both dpERK and Cic shuttle between nucleus and cytosol, we speculate that Cic is phosphorylated in the nucleus, which accelerates its export to cytoplasm, from where it is now imported at a slower rate. As a consequence, Cic spends more time in the cytoplasm where it is degraded. A similar mechanism was reported for degradation of Yan (Aop – FlyBase) and Cf2, two other repressors that respond to Drosophila RTKs (Rebay and Rubin, 1995; Mantrova and Hsu, 1998; Hsu et al., 2001; Tootle et al., 2003). In the early embryo, nuclear exclusion of Cic results in its degradation. In the future, it will be important to test whether this mechanism works in other tissues, both in Drosophila and other species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Trudi Schüpbach for comments on the manuscript, Shelby Blythe for help with qRT-PCR, Jitendra Kanodia for help with the computational model, and Gerardo Jimenez, Ze'ev Paroush, Miriam Osterfield, Alexey Veraksa and Ilaria Rebay for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and National Institutes of Health [RO1-GM077599, R01GM086537 and P50-GM-071508]. S.Y.S. acknowledges partial support by the National Science Foundation [grants DMS-1119714 and DMS-0718604]. J.C. acknowledges support by the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Spanish Government and its Consolider-Ingenio 2010 program. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.084327/-/DC1

References

- Ajuria L., Nieva C., Winkler C., Kuo D., Samper N., Andreu M. J., Helman A., González-Crespo S., Paroush Z., Courey A. J., et al. (2011). Capicua DNA-binding sites are general response elements for RTK signaling in Drosophila. Development 138, 915-924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando R., Mizuno H., Miyawaki A. (2004). Regulated fast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling observed by reversible protein highlighting. Science 306, 1370-1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astigarraga S., Grossman R., Díaz-Delfín J., Caelles C., Paroush Z., Jiménez G. (2007). A MAPK docking site is critical for downregulation of Capicua by Torso and EGFR RTK signaling. EMBO J. 26, 668-677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D., Koppel D. E., Schlessinger J., Elson E., Webb W. W. (1976). Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 16, 1055-1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettegowda C., Agrawal N., Jiao Y., Sausen M., Wood L. D., Hruban R. H., Rodriguez F. J., Cahill D. P., McLendon R., Riggins G., et al. (2011). Mutations in CIC and FUBP1 contribute to human oligodendroglioma. Science 333, 1453-1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppey M., Boettiger A. N., Berezhkovskii A. M., Shvartsman S. Y. (2008). Nuclear trapping shapes the terminal gradient in the Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 18, 915-919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLotto R., DeLotto Y., Steward R., Lippincott-Schwartz J. (2007). Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling mediates the dynamic maintenance of nuclear Dorsal levels during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development 134, 4233-4241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake K., Toth R., Blakey J., Olsson O., Campbell D. G., Prescott A. R., MacKintosh C. (2011). ERK/p90(RSK)/14-3-3 signalling has an impact on expression of PEA3 Ets transcription factors via the transcriptional repressor capicúa. Biochem. J. 433, 515-525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drocco J. A., Grimm O., Tank D. W., Wieschaus E. F. (2011). Measurement and perturbation of morphogen lifetime: effects on gradient shape. Biophys. J. 101, 1807-1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer J. D., Yu P., Kang H., Mandel-Brehm C., Carter A. N., Crespo-Barreto J., Gao Y., Flora A., Shaw C., Orr H. T., et al. (2011). Exercise and genetic rescue of SCA1 via the transcriptional repressor Capicua. Science 334, 690-693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M., Casanova J. (2003). In and out of Torso RTK signalling. EMBO J. 22, 1947-1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor T., Wieschaus E., McGregor A. P., Bialek W., Tank D. W. (2007). Stability and nuclear dynamics of the Bicoid morphogen gradient. Cell 130, 141-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner V. L., Wolfner M. F. (2008). Mechanical stimulation by osmotic and hydrostatic pressure activates Drosophila oocytes in vitro in a calcium-dependent manner. Dev. Biol. 316, 100-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T., McRackan D., Vincent T. S., Gert de Couet H. (2001). Drosophila Pin1 prolyl isomerase Dodo is a MAP kinase signal responder during oogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 538-543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez G., Guichet A., Ephrussi A., Casanova J. (2000). Relief of gene repression by torso RTK signaling: role of capicua in Drosophila terminal and dorsoventral patterning. Genes Dev. 14, 224-231 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez G., Shvartsman S. Y., Paroush Z. (2012). The Capicua repressor-a general sensor of RTK signaling in development and disease. J. Cell Sci. 125, 1383-1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanodia J. S., Rikhy R., Kim Y., Lund V. K., DeLotto R., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Shvartsman S. Y. (2009). Dynamics of the Dorsal morphogen gradient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21707-21712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavousanakis M. E., Kanodia J. S., Kim Y., Kevrekidis I. G., Shvartsman S. Y. (2010). A compartmental model for the bicoid gradient. Dev. Biol. 345, 12-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura-Saito M., Yamazaki Y., Kaneko K., Kawaguchi N., Kanda H., Mukai H., Gotoh T., Motoi T., Fukayama M., Aburatani H., et al. (2006). Fusion between CIC and DUX4 up-regulates PEA3 family genes in Ewing-like sarcomas with t(4;19)(q35;q13) translocation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 2125-2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Coppey M., Grossman R., Ajuria L., Jiménez G., Paroush Z., Shvartsman S. Y. (2010). MAPK substrate competition integrates patterning signals in the Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 20, 446-451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Andreu M. J., Lim B., Chung K., Terayama M., Jiménez G., Berg C. A., Lu H., Shvartsman S. Y. (2011a). Gene regulation by MAPK substrate competition. Dev. Cell 20, 880-887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Paroush Z., Nairz K., Hafen E., Jiménez G., Shvartsman S. Y. (2011b). Substrate-dependent control of MAPK phosphorylation in vivo. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam Y. C., Bowman A. B., Jafar-Nejad P., Lim J., Richman R., Fryer J. D., Hyun E. D., Duvick L. A., Orr H. T., Botas J., et al. (2006). ATAXIN-1 interacts with the repressor Capicua in its native complex to cause SCA1 neuropathology. Cell 127, 1335-1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. J., Chan W. I., Cheung M., Cheng Y. C., Appleby V. J., Orme A. T., Scotting P. J. (2002). CIC, a member of a novel subfamily of the HMG-box superfamily, is transiently expressed in developing granule neurons. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 106, 151-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Fryer J. D., Kang H., Crespo-Barreto J., Bowman A. B., Gao Y., Kahle J. J., Hong J. S., Kheradmand F., Orr H. T., et al. (2011). ATXN1 protein family and CIC regulate extracellular matrix remodeling and lung alveolarization. Dev. Cell 21, 746-757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J., Crespo-Barreto J., Jafar-Nejad P., Bowman A. B., Richman R., Hill D. E., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (2008). Opposing effects of polyglutamine expansion on native protein complexes contribute to SCA1. Nature 452, 713-718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhr U., Chung H.-R., Beller M., Jäckle H. (2009). Antagonistic action of Bicoid and the repressor Capicua determines the spatial limits of Drosophila head gene expression domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21695-21700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malki S. B.-B., Boizet-Bonhoure B., Poulat F. (2010). Shuttling of SOX proteins. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 411-416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantrova E. Y., Hsu T. (1998). Down-regulation of transcription factor CF2 by Drosophila Ras/MAP kinase signaling in oogenesis: cytoplasmic retention and degradation. Genes Dev. 12, 1166-1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T., Ibata K., Park E. S., Kubota M. M., Mikoshiba K., Miyawaki A. (2002). A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 87-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Kang W., Leung B., McLeod M. (2003). Ste11p, a high-mobility-group box DNA-binding protein, undergoes pheromone- and nutrient-regulated nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3253-3264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebay I., Rubin G. M. (1995). Yan functions as a general inhibitor of differentiation and is negatively regulated by activation of the Ras1/MAPK pathway. Cell 81, 857-866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roch F., Jiménez G., Casanova J. (2002). EGFR signalling inhibits Capicua-dependent repression during specification of Drosophila wing veins. Development 129, 993-1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüpbach T., Wieschaus E. (1989). Female sterile mutations on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Maternal effect mutations. Genetics 121, 101-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F., Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1992). Torso receptor activity is regulated by a diffusible ligand produced at the extracellular terminal regions of the Drosophila egg. Cell 71, 987-1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stros M., Launholt D., Grasser K. D. (2007). The HMG-box: a versatile protein domain occurring in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 2590-2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabad J., Erdélyi M., Hoffmann G., Szidonya J., Wright T. R. F. (1989). Isolation and characterization of dominant female sterile mutations of Drosophila melanogaster. II. Mutations on the second chromosome. Genetics 122, 823-835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tootle T. L., Lee P. S., Rebay I. (2003). CRM1-mediated nuclear export and regulated activity of the receptor tyrosine kinase antagonist YAN require specific interactions with MAE. Development 130, 845-857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.