Abstract

Loss of Transforming Growth Factor β Receptor III (TβRIII) correlates with loss of Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) responsiveness and suggests a role for dysregulated TGF-β signaling in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) progression and metastasis. Here we identify that for all stages of ccRCC TβRIII expression is down-regulated in patient-matched tissue samples and cell lines. We find that this loss of expression is not due to methylation of the gene and we define GATA3 as the first transcriptional factor to positively regulate TβRIII expression in human cells. We localize GATA3s binding to a 10bp region of the TβRIII proximal promoter. We demonstrate that GATA3 mRNA is down-regulated in all stages of ccRCC, mechanistically show that GATA3 is methylated in ccRCC patient tumor tissues as well as cell lines and that inhibiting GATA3 expression in normal renal epithelial cells down-regulates TβRIII mRNA and protein expression. These data support a sequential model whereby loss of GATA3 expression via epigenetic silencing decreases TβRIII expression during ccRCC progression.

Keywords: Transcriptional Regulation, GATA3, Type III Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor, methylation, clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 3% of all malignancies reported each year and is the sixth leading cause of cancer death. Even though localized RCCs can be removed by surgery, ~30% of these diagnosed patients will develop metastasis even after nephrectomy (Pantuck et al., 2001). Incidence of RCC is twice as common in males and usual onset is seen in patients between the ages of 50–70. The most frequently diagnosed form of the disease is clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) which accounts for around 80% of the RCCs diagnosed in the US. The development of metastasis greatly decreases the survival of ccRCC patients with 5 year survival rates of <10% in patients diagnosed with stage 4 disease (Motzer et al., 1999). Even though numerous treatments have been tested in addition to surgery such as radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, vaccines and immunotherapy, they have all had very little benefit on being able to reduce metastasis (Wood, 2007). Early diagnosis of this disease is essential for intervention and cure due to the lack of effective treatments available for later stages and metastatic disease.

TβRIII, also known as betaglycan, is the most abundantly expressed TGF-β cell surface receptor and shows affinity for all 3 TGF-β ligand isoforms with highest affinity for binding the TGF-β2 ligand. While it does not contain a functional kinase domain, TGF-β ligands binding to TβRIII affords presentation of the ligand to the type II TGF-β receptor (TβRII), leading to association and phosphorylation of the type 1 receptor (TβRI), which further phosphorylates Smad2 or Smad3 [Reviewed in (Elliott and Blobe, 2005; Gordon et al., 2008)]. Loss of or reduced TβRIII expression has been observed in human prostate, ovarian, endometrial, pancreas, breast, RCC and lung cancer, (Chakravarthy et al., 1999; Copland et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2007; Finger et al., 2008; Florio et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2008; Hempel et al., 2007; Nima Sharifi, 2007; Turley et al., 2007). We and others have previously identified that TβRIII loss promotes decreased cell responsiveness to TGF-β signaling, an important step in tumor progression (Copland et al., 2003; Stenvers et al., 2003). These findings suggest a tumor suppressor role for TβRIII in normal cells, which is further supported by studies in which restoring TβRIII expression resulted in decreased migration, invasion (Copland et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2007; Finger et al., 2008; Turley et al., 2007) and increased apoptosis (Margulis et al., 2008) in vitro and decreased tumorigenesis and metastasis in vivo (Copland et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2007; Finger et al., 2008; Turley et al., 2007). Mechanistically, TβRIII signals through the p38 MAPK pathway to induce apoptosis (Margulis et al., 2008) and through activation of Cdc42 (Mythreye and Blobe, 2009) and inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway (You et al., 2009) to inhibit cell migration.

The GATA protein family can be divided by body distribution. GATA1–3 are primarily expressed in hematopoietic cells while GATA4–6 are expressed in endoderm-derived tissues (Ho and Pai, 2007). GATA3, a protein essential for regulating Th2 development and function, is expressed during human kidney embryogenesis (Labastie et al., 1995) with GATA3 haploinsufficiency responsible for hypoparathyroidism, sensorineural deafness and renal anomalies (HDR) syndrome in humans (Van Esch et al., 2000). Recent investigations show GATA3 maintains differentiation in mammary gland ductal cells (Kouros-Mehr et al., 2006) and that GATA3 expression loss strongly predicts poor clinical outcome, high tumor grade and large tumor size in breast cancer patients (Mehra et al., 2005). In human ccRCC patient samples protein and mRNA expression of GATA3 decreases compared to normal renal tissue (Tavares et al., 2008). Abnormal GATA3 expression is also observed in human pancreatic cancer with GATA3 expression localized to the cytoplasm of the cancer cells (Gulbinas et al., 2006).

Our examination of TβRIII expression levels in all stages of ccRCC compared to normal patient-matched tissues shows that TβRIII expression loss occurs at all stages of ccRCC (localized and metastatic) and this loss is not due to methylation. We cloned and identified a specific promoter region governing TβRIII gene expression and identified GATA3 as a transcription factor that plays a positive role in the expression of TβRIII mRNA in normal renal and ccRCC cells. We also found decreased GATA3 expression in all stages of ccRCC, partially due to methylation silencing of the gene. Our results identify GATA3 as a transcription factor whose loss in ccRCC is responsible for the loss of TβRIII expression. These findings have important biological consequences since re-expression of TβRIII in ccRCC leads to apoptosis via activation of phosphorylated p38.

Results

TβRIII expression is lost in ccRCC

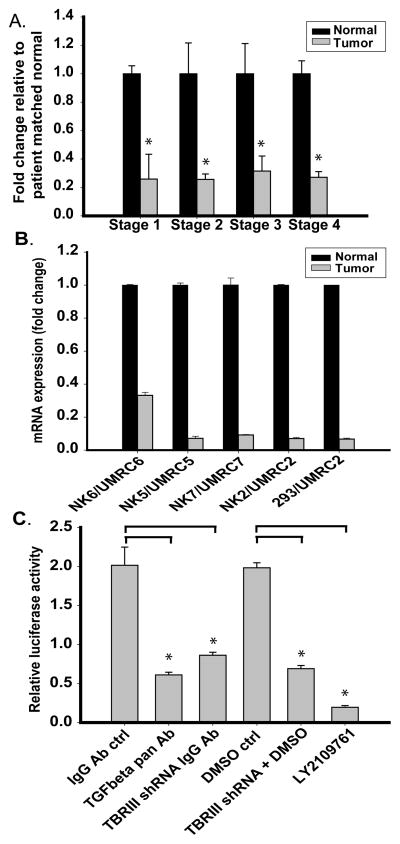

Utilizing Real Time PCR analysis we analyzed TβRIII expression in a cohort of 10 patient-matched normal renal and ccRCC matched samples per stage (1–4) (Figure 1A). We identify that TβRIII expression loss is an early event in ccRCC and remains down-regulated in all stages of ccRCC. We also analyzed TβRIII expression in cell lines previously created from patient-matched normal and ccRCC tissue samples (Figure 1B). A 67% TβRIII expression decrease was observed in Stage 1 ccRCC cells (UMRC6) compared to normal-matched renal cells (NK6). 90% expression loss and greater was observed in Stage 3 (UMRC5 and UMRC7) and Stage 4 cell cells (UMRC2). Due to limited passage potential of normal renal cells (NKs) we analyzed TβRIII expression loss in UMRC2s compared to human embryonic renal cell line HEK293 and showed a comparable expression loss. These results identify loss of TβRIII as an early event in ccRCC.

Fig. 1.

Expression and biological activity of TβRIII is attenuated in ccRCC. A. Real Time PCR analysis of the expression of TβRIII in patient-matched tissues for all stages of ccRCC (n=10 samples per stage) using primers specific to translated exon regions of the TβRIII mRNA. B. Real Time PCR analysis of TβRIII mRNA expression in patient-matched normal renal primary cultured cells and cRCC cell lines. (Stage 1, UMRC6; Stage 3, UMRC5 and UMRC7; Stage 4, UMRC2). The human embryonic renal cell line, HEK 293 cells were used as “normal” renal cells. Data is plotted as the mean +/− standard deviation (SD). C. HEK 293 cells were infected with a non-target or TβRIII shRNA before undergoing transient transfection with a Smad 2/3 transcriptional reporter (CAGA12/luciferase). Levels of TβRIII mRNA expression were reduced by 60% after TβRIII shRNA infection (data not shown). These non-target or TβRIII shRNA infected cells were treated with a pan TGF-β neutralizing antibody or 50μM LY2109761 with appropriate controls and analyzed for luciferase activity to demonstrate that TGF-β signaling was mediated via TβRIII.

Loss of TβRIII is associated with decreased responsiveness to TGF-β signaling

We evaluated TβRIII-dependent function in normal and ccRCC cells by examining Smad-dependent transcription (Figure 1C). Normal renal cells infected with lentiviral TβRIII shRNA compared to non-target shRNA-infected controls lead to greater than 60% attenuation of luciferase activity in cells transiently transfected with CAGA12/luciferase (Smad 2/3 reporter). TβRIII mRNA expression levels were reduced by 60% in TβRIII shRNA cells compared to non-target infected controls (data not shown). Addition of a pan TGF-β neutralizing antibody or exposure to LY2109761, a TGF-β receptor I/II kinase inhibitor, decreased luciferase activity to 70% and 90%, respectively (Figure 1C). These results show that loss of TβRIII leads to decreased responsiveness of cells to TGF-β signaling.

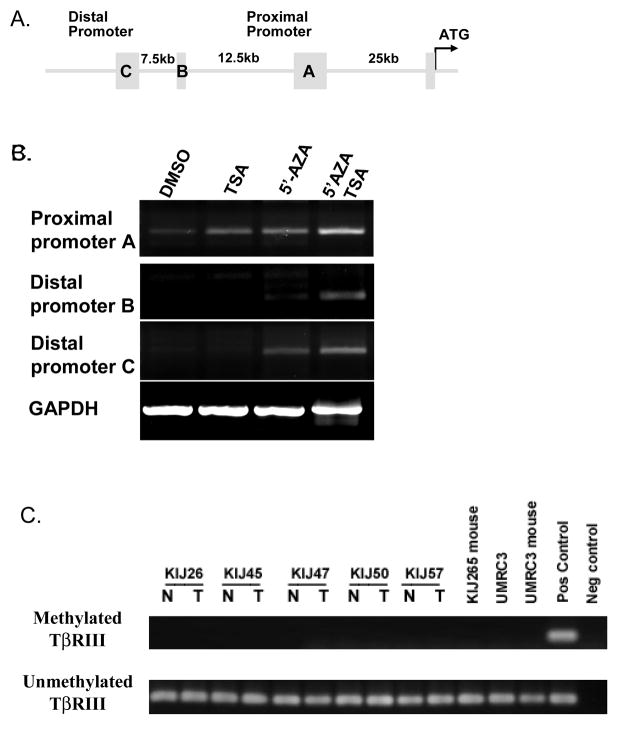

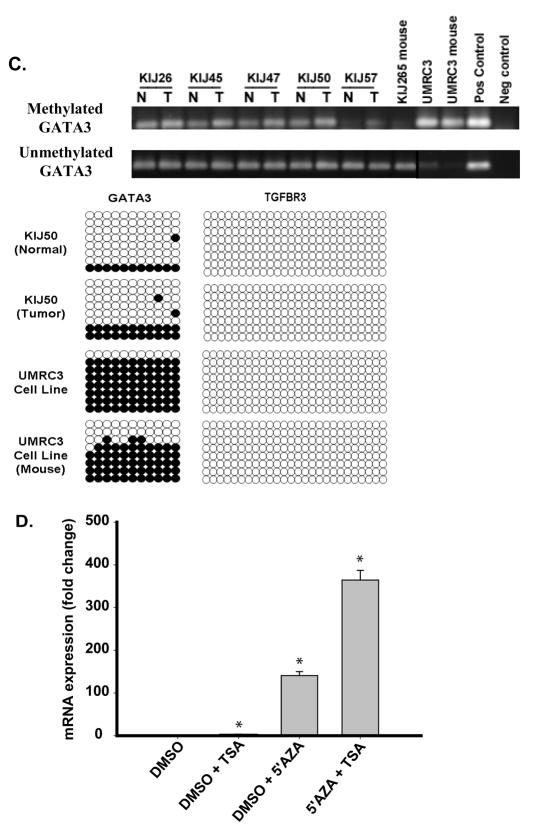

Methylation and HDAC inhibitors restore TβRIII mRNA expression in ccRCC cells

Partial cloning and characterization of the human TβRIII gene promoter has been previously described (Hempel et al., 2008). The promoter contains 2 transcription start sites and three 5′ untranslated regions (5′UTR). The sequence flanking the 5′UTR C is designated as the distal promoter (45kb upstream of the ATG start site) and the region flanking the 5′UTR A the proximal promoter (25kb from ATG) (Figure 2A). Real Time PCR primer and probe sets were designed for 5′ untranslated regions (5′UTR) A, B and C allowing for identification of the active TβRIII gene promoter. Real time analysis of 5′UTR B and C showed little to no expression in the UMRC2 stage 4 ccRCC cell line (Figures 2B) and no expression was observed in all of the patient-matched normal renal and cancer samples at any stage of RCC (n=40). Expression of 5′UTR A, the proximal promoter, was present in UMRC2 cells (Figures 2B).

Fig. 2.

Re-expression of the proximal and distal promoters of TβRIII following exposure to methylation and HDAC inhibitors. A. The 3 5′UTR regions (A, B and C) and the distance of these promoters from the ATG start site of the TβRIII gene are shown. B. Using PCR specific forward primers for each of the 5′UTRs (A, B, & C) and a reverse primer located in the first coding exon of the TβRIII gene, we identify that mRNA expression of the 3 promoters are upregulated following exposure of UMRC2 cells to 10μM 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5′AZA) and 0.5μM TSA. C. Patient-matched samples (n=5) and ccRCC derived cell lines (UMRC3) grown in athymic nude mice (KIJ265 mouse and UMRC3 mouse) were examined for methylation of the TβRIII gene (N=normal, T=tumor). Methylation specific PCR was carried out on bisulfite-treated genomic DNA. Specific primers were utilized to amplify methylated or unmethylated sequences of the TβRIII gene.

Previous investigations examining prostate cancer suggest that epigenetic silencing affects TβRIII expression loss (Turley et al., 2007). We treated UMRC2 cells with the methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and/or the pan HDAC inhibitor TSA using treatment protocols as previously published (Hempel et al., 2007). Pre-exposure of cells to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine before TSA treatment induced a robust re-expression of the distal promoter and increased proximal promoter transcript expression (Figures 2B). Basal expression levels of the promoters imply that TβRIII expression is governed by the proximal promoter: no expression of the distal promoter is observed in patient normal renal or ccRCC tissue samples (data not shown). These data suggest that epigenetic changes play a role in silencing these TβRIII gene promoters.

TβRIII gene is not methylated

We examined TβRIII gene methylation status in 5 patient-matched tissue samples and three RCC cell lines. We were unable to detect TβRIII gene methylation in any of these samples (Figure 2C).

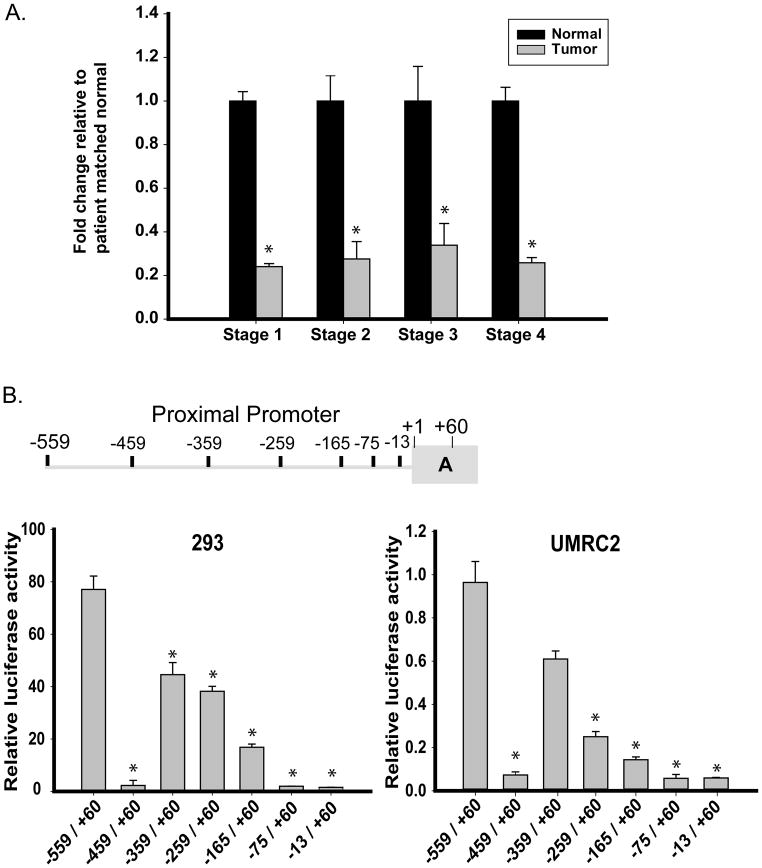

Real Time PCR analysis of patient-matched samples from all ccRCC stages revealed a similar expression loss of the proximal promoter (Figure 3A) compared to TβRIII gene analysis in the same patient samples (Figure 1A). These expression similarities prompted further investigations of the proximal promoter utilizing a luciferase reporter assay.

Fig. 3.

Expression of TβRIII mRNA resides in the proximal promoter. A. Expression of the TβRIII mRNA using PCR primers specific to the 5″ region of the untranslated region of the proximal promoter in patient-matched normal renal and ccRCC tissues identify identical expression patterns to that seen in Figure 1A. B. Deletions within the proximal promoter (identified within the cartoon) lead to a significant loss of luciferase activity. All deletions were created within the pGL3Basic vector and transfected into cells as described in the Experimental Procedures section. Results were normalized to TK renilla luciferase activity, expressed as relative luciferase activity (RLU) and shown as the mean +/− SD (n=3). C. Positive regulator of proximal promoter expression is identified to be within the first 50bp of the −559/+60 promoter. A representative diagram is shown for the sequence of the first 50bp of the −559/+60 proximal promoter identifying putative transcription factor binding sites and areas deleted or mutated within this region. Cells were transfected with the deletion constructs, samples collected and analyzed as in Materials and Methods. The data was normalized to TK renilla luciferase activity and shown as the mean +/− SD (n=3).

The full-length proximal promoter luciferase construct (−559/+60) was transfected into HEK293 and UMRC2 cells identifying high luciferase activity in HEK293 cells compared to UMRC2s (Figure 3B). Deletions of the promoter identified that an enhancer element was present between bases −559 and −459 from the proximal transcriptional start site as seen by the loss of activity in both transfected cell lines (Figure 3B). Further deletions within the −559/−459 region of the proximal promoter identified the enhancer element located between base −559 and −534 of the proximal transcriptional start site (Figure 3C). Potential transcription factor binding sites were identified using the web-based TFSEARCH (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html) and a threshold score of 75% (Figure 3C). All identified transcription factors bind to a similar inner core sequence within the −559/−534 proximal promoter region. Deletions and mutations within this area were created and expression analyzed in HEK293 and UMRC2 cell lines.

Deletion of the −549/−539 TβRIII proximal promoter region resulted in complete luciferase expression loss in HEK293 cells and reduced expression in UMRC2s, verifying that the 10 base pair core region contains the TβRIII proximal promoter activation element (Figure 3C). Using TFSEARCH, mutations within this region negated all identified putative binding sites and demonstrated substantial expression loss of the TβRIII proximal promoter in both cell lines, further verifying that the −549/−539 region contains putative transcription factor binding site(s) responsible for the promoter’s expression.

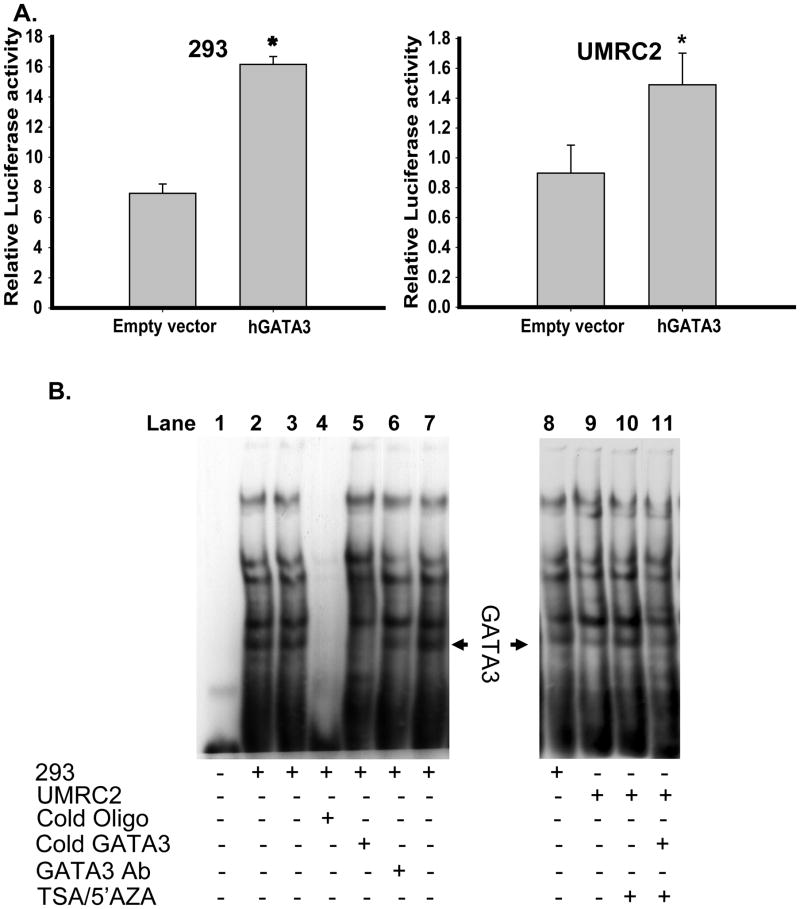

GATA3 binds to the −559/−534 region of the TβRIII proximal promoter

One of the putative transcription factors identified within this region was that of GATA3. Transient transfection of GATA3 and the −559/+60 TβRIII proximal promoter in HEK293 and UMRC2s revealed upregulation of luciferase reporter activity (Figure 4A). We further analyzed GATA3 as a putative transcription factor interacting with the −559/−534 TβRIII proximal promoter region by EMSA techniques utilizing a biotin-labeled probe corresponding to this 25bp region. Addition of HEK293 nuclear extracts to this probe produced multiple protein bands bound to this region (Figure 4B, lane 2, 3, 7 and 8). Competition for binding using excess non-biotin-labeled probe demonstrates loss of all bands (Figure 4B, lane 4). Addition of a non-biotin-labeled GATA3 consensus sequence in excess, or an antibody specific for GATA3 identified a single, specific band whose intensity was decreased by these treatments (Figure 4B, lanes 5 and 6 respectively), indicative of specificity for GATA3 binding.

Fig. 4.

hGATA3 is identified as a transcriptional factor positively regulating TβRIII mRNA via the TβRIII proximal promoter. A. The TβRIII proximal promoter construct (−559/+60 luciferase), TK renilla luciferase, human GATA3 or an empty expression vector control were transiently transfected into HEK293 and UMRC2 cell lines as described in Materials and Methods. After collection, cell lysates were analyzed for firefly luciferase activity and normalized to TK renilla luciferase. Results are expressed as mean +/−SD (* = p<0.05 student T-test). B. EMSA analysis was performed on nuclear extracts from HEK 293 and UMRC2 cells as described in the Experimental Procedures section to identify transcriptional factor(s) binding to the first 25bp sequence of the TβRIII proximal promoter. Incubation with a non-biotin labeled GATA3 consensus oligo sequence or an antibody specific for GATA3 identified a single band corresponding to the GATA3 DNA binding complex. 293 nuclear extracts were used as a control to identify loss of GATA3 binding in UMRC2 cells compared to 293 nuclear extracts and TSA/5′AZA treated UMRC2 cells.

Nuclear extracts from UMRC2s demonstrate decreased intensity of the GATA3-specific band (Figure 4B, lane 9 compared to lane 8). When UMRC2 cells are treated with TSA and 5′AZA, the GATA3 band is restored (Figure 4B, lane 10). Addition of excess cold GATA3 oligonucleotide consensus sequence reduced the band intensity (Figure 4B, lanes 11). Thus GATA3 can bind to the 25bp region of the TβRIII proximal promoter in normal and ccRCC cells.

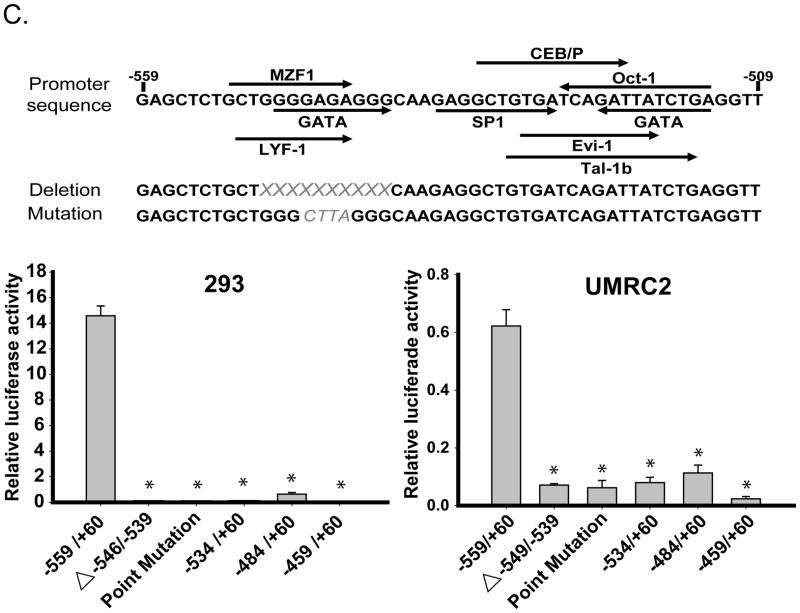

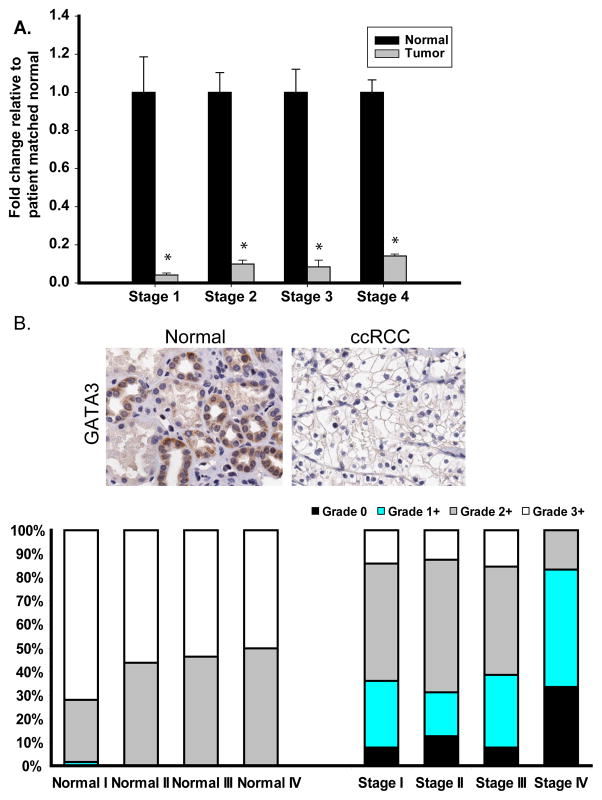

GATA3 expression loss in ccRCC

A recent, publication showed GATA3 mRNA down-regulation in all stages of ccRCC (Tavares et al., 2008). Analysis of our 10 patient-matched normal and ccRCC tissues by Real Time PCR further confirms that GATA3 expression is lost in early-stage ccRCC (stage 1) and is also down-regulated in all other stages (Figure 5A). These finding were confirmed in experimental cell lines comparing Stage 2 and 4 UMRC cells with expression levels of GATA3 in the HEK293 cells (data not shown). Tissue Matched Arrays (TMA) for all stages of RCC were analyzed for GATA3 expression after immunohistochemical staining showing loss of intense GATA3 staining (3+) in ccRCC compared to normal-matched samples (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5.

Expression of GATA3 is down-regulated in ccRCC. A. Real Time analysis of patient-matched normal renal and ccRCC tissue samples identified loss of GATA3 mRNA expression in all 4 stages of ccRCC (10 samples per stage). B. IHC analysis identified loss of GATA3 protein expression in all ccRCC stages compared to normal matched tissue. Representative images from normal and stage 4 ccRCC stained tissue are shown and graded scores were converted into percentage categories and graphed. C. Patient-matched normal renal and ccRCC tissue and ccRCC cell lines were investigated for their GATA3 methylation status as described previously. Methylation of GATA3 was observed to be present in normal (N) and tumor tissues (T) but was more highly methylated in ccRCC tissue samples. Eight clones were sequenced for each sample with open circles representing unmethylated CpG sites and closed circles representing methylated CpG sites. TβRIII bisulphate genomic sequencing was included to confirm negative methylation. D. Treatment of UMRC2 cells with TSA and or 5′AZA increase mRNA expression of GATA3 compared to non-treated controls. Cells were treated (10μM 5′AZA/0.5μM TSA) and collected as described in the Materials and Methods section before undergoing Real Time PCR analysis. Data is shown as mean +/−SD (n=3).

GATA3 expression loss in ccRCC through epigenetic changes

We examined GATA3 genes methylation status in 5 patient-matched tissue samples and 3 RCC cell lines. In all samples the GATA3 gene was methylated but was more strongly methylated in tumor samples (Figure 5C). Results were confirmed by bisulfite genomic sequencing (Figure 5C), determining that methylation of DNA is playing a role in the loss of expression of GATA3 in ccRCC. In contrast bisulfite genomic sequencing determined that DNA methylation was not a cause of TβRIII expression loss in ccRCC (Figure 5C). Treatment of UMRC2s with 5′AZA or 5′AZA plus TSA dramatically upregulates GATA3 mRNA (Figure 5D), similar to the re-expression of TβRIII mRNA (Figure 2). These findings identify loss of GATA3 in all stages of ccRCC and that this loss of expression is in part due to epigenetic silencing of the gene.

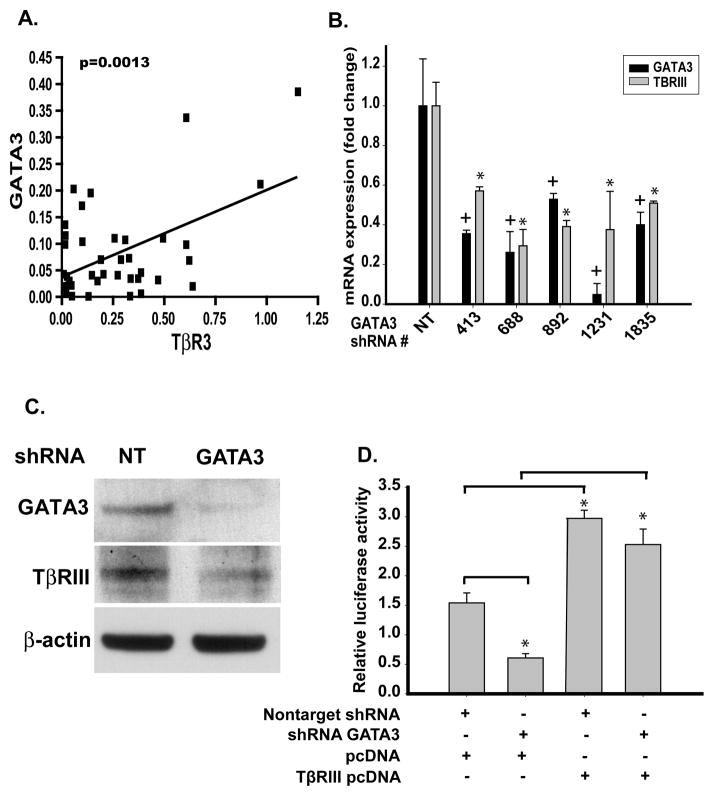

Endogenous GATA3 regulates TβRIII mRNA

In ccRCC patient tissue GATA3 and TβRIII mRNA demonstrated a statistically significant correlation (p=0.0013) intimating a mechanistic relationship between GATA3 and TβRIII (Figure 6A). Silencing GATA3 in HEK293 cells using 5 different lentiviral shRNAs against different GATA3 gene regions led to concomitant down-regulation of TβRIII mRNA (Figure 6B) and GATA3 protein levels (Figure 6C). Furthermore, this decrease in mRNA expression of GATA3 in HEK293 cells lead to decreased expression of TβRIII protein (Figure 6C). This loss of GATA3 expression disrupts Smad signaling as identified by the CAGA12/luciferase reporter assay. This disruption of TGF-β signaling is mediated via loss of TβRIII since re-expression of TβRIII rescues this phenotype (Figure 6D). Repeated attempts to re-express GATA3 in ccRCC cell lines have resulted in no observed upregulation of GATA3 protein expression. These results identify that loss of GATA3 downregulates TβRIII mRNA and protein expression leading to decreased TGF-β signaling responsiveness mediated through TβRIII.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of endogenous GATA3 down-regulated TβRIII mRNA expression in normal renal cells. A. Correlation of TβRIII and GATA3 expression in stage 1–4 ccRCC patient-matched normal and ccRCC tissue samples (p=0.0013). B. Infection of HEK293 cells with non-target and 5 variant shRNA lentiviral constructs specific for GATA3 were harvested before undergoing Real Time PCR analysis. Results are shown as mean fold expression compared to non-target controls +/− SD (n=3). C. Western blot analysis of lentiviral shRNA GATA3 infected 293 cells was used to verify loss of GATA3 protein expression and identify modulations of TβRIII.β-actin was used as a protein loading control. D. Lentiviral knockdown of GATA3 in 293 cells decreases TGF-β/Smad responsiveness in normal cells mediated via the loss of TβRIII. Cells were treated as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Discussion

We identify GATA3 as the first transcription factor known to positively regulate human TβRIII mRNA and protein expression. This is also the first demonstration of the molecular mechanism for the attenuation of TβRIII in ccRCC. We found that TβRIII expression loss is not due to direct gene methylation but by methylation of the transcription factor regulating TβRIII mRNA. Our data uniquely indicates that TβRIII gene expression regulation in the human kidney is via the proximal promoter and that the distal promoter is silenced in normal and tumor tissues. We also mapped the proximal promoter region that confers TβRIII transcription regulation by GATA3. Finally loss of GATA3 attenuates the ability of normal cells to respond to TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway mediated via the loss of TβRIII. These findings reveal a novel positive TβRIII expression regulator in normal renal cells and enhance our understanding of the mechanisms involved in TβRIII loss in ccRCC.

Although little is known about the regulation of the human TβRIII promoter, the mouse TβRIII promoter is positively regulated by retinoic acid and the myogenic differentiation factor MyoD (Lopez-Casillas et al., 2003) and prostaglandin E2 increases expression of TβRIII in rat osteoblasts (McCarthy et al., 2007). Our group was the first to clone the human TβRIII promoter (Hempel et al., 2008) and now we identify that, in normal renal cells, TβRIII expression is governed by its proximal promoter and the area of positive gene regulation is within the −559/−534bp promoter region. These combined data suggest that negative and positive regulatory sites exist within TβRIII’s proximal promoter (Hempel et al., 2008). This is supported by our proximal promoter deletion data that shows a negative regulatory element in the −459/+60 to −359/+60 region; deletion of this region leads to re-expression of the promoter, but not back to the levels observed with the full-length promoter. We have identified the positive regulator of TβRIII expression within normal renal cells as the transcription factor GATA3. Loss of GATA3 leads to decreased TβRIII mRNA and protein expression.

As GATA3 is expressed in the developing human embryonic kidney, and is shown to be expressed in normal renal proximal tubules, the proposed cell type of origin for ccRCC, this would suggest GATA3 has a yet-to-be-described role in normal kidney cell function and/or maintenance. In developing mammary glands, GATA3 has been identified as necessary for differentiation and development of luminal cells (Kouros-Mehr et al., 2008b). Loss of GATA3 expression in the nephric duct of the developing kidney leads to aberrant cellular proliferation and elongation of the nephric duct (Grote et al., 2006) suggesting that GATA3 plays a role in cell cycle regulation of kidney cells. This regulatory effect of GATA3 on cell cycle regulation has been previously identified in the mammary glands with non-proliferating cells showing high expression levels of GATA3 whilst highly proliferative cells have low levels of expression (Kouros-Mehr et al., 2006). Restoration of GATA3 in late breast carcinogenesis mouse models stimulated cellular differentiation and suppressed tumor dissemination (Kouros-Mehr et al., 2008a). Within our data we show high expression of GATA3 in normal renal patient samples compared to low levels of expression in matched tumor samples. This loss of expression of GATA3 is an early event in ccRCC and correlates with loss of TβRIII within patient matched samples which we have identified to be governed by GATA3s transcriptional regulation of the TβRIII proximal promoter. Previous findings from our group have identified that re-expression of TβRIII in ccRCC induces apoptosis mediated via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway (Margulis et al., 2008). We can therefore hypothesize that loss of GATA3 expression via methylation of the gene in normal renal cells is able to induce aberrant cell proliferation whereas loss of TβRIII allows escape of these cells from apoptosis. However, even though GATA3 has been identified to play a role in the developing kidney, nothing is known about the role of GATA3 in adult normal kidney much less the role of GATA3 in ccRCC carcinogenesis and progression. Loss of GATA3 expression in the kidney may lead to de-differentiation of normal renal cells as well as decreasing TβRIII expression leading to loss of TFG-β responsiveness. In general TGF-β/Smad 2/3 signaling promotes differentiation and apoptosis in epithelial cells (Massague, 2008).

Our findings suggest that loss of GATA3 is an early event in the onset of ccRCC, an event that leads to loss of TβRIII expression and subsequent loss of TGF-β regulation. Treatment of ccRCC cells with a methyltransferase inhibitor and a pan HDAC inhibitor induces GATA3 re-expression which in turn regulates expression of TβRIII hypothetically leading to activation of the p38 MAPK pathway and inducing apoptosis within these cells (Margulis et al., 2008). This would suggest that GATA3 should be investigated as a novel molecular target for ccRCC therapies. Current work is directed at identifying mechanisms to selectively re-express GATA3 within ccRCC cells and to identify pathways and cellular processes that are governed by this transcription factor.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

UMRC2 cells were maintained in high glucose DMEM containing 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B. HEK293 cells were maintained in αMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B, non-essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate and sodium bicarbonate. Cell lines were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. UMRC2, UMRC3, UMRC5, UMRC6 and UMRC7 ccRCC cell lines and patient-matched NK2, NK5, NK6 and NK7 normal human primary renal epithelial cells were a kind gift from Dr. E. Barton Grossman, UT M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

To investigate 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine’s and/or TSA’s effect on reversing gene silencing cells were treated with either DMSO for 4 days, DMSO for 4 days with the last 16 hours combined with trichostatin A (TSA, histone deacetylase inhibitor 0.5μM), 4 days 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (10μM) with the last 16 hours combined with DMSO or 4 days 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (10μM) combined with TSA (0.5μM) for the final 16 hours.

RNA extraction and Real Time PCR

Cellular RNA was extracted from UMRC2 and HEK293 cells using the RNAqueous –Midi Kit (Ambion) per manufacturer’s instructions. This purified RNA was reversed transcribed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) using provided random primers. For subsequent Real Time PCR quantifications, 20ng of template cDNA were utilized per reaction. Applied Biosystems’ assays-on-demand- 20× primers and Taqman MGB probes for TβRIII (Hs00234257_m1), GATA3 (Hs00231122_m1), GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1) and 18S (Hs99999901_s1) were used for Real Time PCR. Forty cycles were undertaken on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System. Samples were normalized to either 18S or GAPDH and ΔΔCt methods used to calculate fold expression changes of mRNA (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). For RT-PCR, 200ng of cDNA was used with the ThermalAce DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used were 5′-GAACCGCATGAGCCTGAAGC-3 ′ (5 ′ UTR C), 5 ′-GCAAGGACACAACATCAGAGGG-3′ (5′UTR B), 5′-GTCCGGATGGCGTAGTTTT-3′ (5′UTR A) and 5′-CGTCTCGTCCAGTCACTTCA-3′ (TBRIII promoter reverse primer). Samples were amplified for 35 cycles and visualized by electrophoresis using a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (Invitrogen).

Lentiviral infection

Lentiviral constructs to package self-inactivating lentiviruses were made in the pLKO.1 vector (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO). We purchased lentiviruses from the human clone set NM_002051 for GATA binding protein 3 from Sigma Aldrich and a random scrambled sequence was used for the non-target vector. Target renal cells were plated in 10 cm plates and grown to 70% confluence before infection along with 7.5 μg/ml polybrene per manufacturer’s protocol. Infected cells were selected using 2.5 μg/ml puromycin (SigmaAldrich).

Genomic DNA isolation

Patient samples were collected and processed by this laboratory as previously described in accordance with Institutional Review Board protocols (Gumz et al., 2007). Patient-matched human RCC and normal tissue collected from distant cortex, along with several cell lines, were lysed for genomic DNA isolation using the Aquapure Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Microarray gene array analyses

Microarray gene expression data on GATA3 and TβRIII in 10 early stage ccRCC samples (5 Stage1 and 5 Stage2 ccRCC) and 10 tumor-matched normal renal samples were analyzed as previously described (Gumz et al., 2007).

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) and bisulfite genomic sequencing (BGS)

Methylation status of GATA3 and TβRIII genes in human RCCs, their matched normal control tissues, and RCC cell lines were first tested with methylation-specific PCR as previously described (Gumz et al., 2007). Primer sequences and annealing temperatures used were ACGATTTTCGATTTTTCGACGGTAGGAGTTTTTC (sense) and GACTATACTCGCGCCCTCTCGCCGA (antisense) for methylated GATA3 at 62°C, ATGATTTTTGATTTTTTGATGGTAGGAGTTT (sense) and TCAACTATACTCACACCCTCTCA (antisense) for unmethylated GATA3 at 58°C, CGTAGTAGTTGTCGGAGTTCGTC (sense) and ACCGACACGTACCTCGAAAACGA (antisense) for methylated TβRIII at 62°C, and TGTAGTAGTTGTTGGAGTTTGTT (sense) and ACCAACACATACCTCAAAAACAA (antisense) for unmethylated TβRIII at 58°C. Bisulfite-treated human genomic DNA (Novagen) and CpGenome™ universal methylated DNA (Chemicon) were positive controls for unmethylation and methylation reactions, respectively.

Methylation status of representative samples was confirmed by bisulfite genomic as previously described (Gumz et al., 2007). BGS Primer sequences and annealing temperatures were GTTGGGTGAGTTATTATTATTT (sense) and ATATTAAAAAACACATCCACCTC (antisense) for GATA3 at 56°C, and GTTTTTTGTAGGAGGTGAGAG (sense) and CAACCTACAAAACCCACAAC (antisense) for TβRIII at 60°C.

Antibodies and Western blot analyses

Cell lysates were collected, quantified and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane as previously described (Copland et al., 2006). Membranes were hybridized with mouse anti-GATA3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or rabbit anti-TβRIII (R&D Systems) overnight at 4°C before treatment with species-specific horseradish peroxidase IgG antibodies (Jackson Laboratory) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Detection was performed using chemiluminescent detection substrate (ECL, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Promoter deletion constructs

Creation of the −559/+60 TβRIII proximal promoter luciferase construct is previously reported (Hempel et al., 2008). Deletions of this construct were created using the QuikChangeII Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) per manufacturer’s instructions using the primers: GATA3 deletion sense 5′-ggtaccgagctctgctcaagaggctg-3′; GATA3 mutation sense 5′-ggtaccgagctctgctgggcttagggcaagaggctg-3′; −534 sense 5′-cgataggtaccggctgtgatcagattatctgagg-3′; −484 sense 5′-cgataggtaccgaaccaaatgaaaatccaactcttcc-3′; −459 sense 5′-cgataggtacccagggagccctggaaag-3′. Deletions were verified by DNA sequencing before purification with PureLink HiPure Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Invitrogen).

Luciferase assays

Promoter constructs were transfected in triplicate (0.5μg DNA/well) with 10ng/well control Renilla luciferase reporter using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche). Cells were lysed 24 hours post-transfection and luciferase activity measured using the Duel Luciferase Kit (Promega) per manufacturer’s instructions. For the CAGA12 assay, 24 hours post-transfection cells were treated with 25μg/ml TGF-β pan neutralizing antibody, 25μg/ml goat IgG control, 50μM LY2109761 (TGF-β receptor I/II kinase inhibitor, gift Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis IN) or DMSO vehicle control for 24 hours.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Oligos for the first 25bp of the TβRIII proximal promoter were purchased (Integrated DNA Technologies) with a 5′-end forward strand biotin label 5′GAGCTCTGCTGGGGAGAGGGCAAGA3′. Control oligos without biotin labeling were purchased as was the same region of the proximal promoter with a GATA3 binding site mutation (5′-GAGCTCTGCTGGGCCCCGGGCAAGA-3′) and a GATA3 consensus sequence (5′-GACCTGAGATAGGGCGGTT-3′). Nuclear extracts were isolated as previously described (Cooper et al., 2005).

For shift assays, 1μg of nuclear protein was incubated in 20μl of a buffer containing 10mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 50mM KCl, 0.1mM EDTA, 2.5mM dithiotreitol, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40 and 0.05μg/μl poly (dI-dC) on ice. Unlabelled probe and/or specific antibody GATA3 sc-268× (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added for 45 minutes on ice. Biotin labeled probe was added 20 minutes prior to gel loading. Samples were resolved on a nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE before transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche) in 0.25× TBE. Transferred DNA was cross-linked to the membrane by 120mJ/cm2 UV light from a Spectrolinker XL1000 UV Crosslinker (Spectronics Corporation). Membranes were treated, activated and exposed to film using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit as manufacturer-directed (Pierce).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Patient-matched normal, renal and ccRCC tissue samples were treated as previously described (Gumz et al., 2007). Sections were immunostained using an antibody against human GATA3 (1:400; IMGENEX). Tissue staining intensity were graded on signal intensity (0, 1+, 2+, 3+ grade) and percentage positive cells (0≤5%, 1+=5–20%, 2+=20–50%, and 3+≥50%). If insufficient tissue existed, samples were excluded from the study. Images were obtained using a Scanscope XT (Aperio) and Spectrum software.

Statistical Analysis

One outlier each for stage 2 and 3 patient matched samples were observed but removed from analysis due to the value being an extreme outlier as identified using the formula χ>Q3+3(Q3−Q1). Data are presented as the mean ± SD and comparisons of treatment groups were analyzed by two–tailed equal variance Student’s t test. Data for comparison of multiple groups are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed by ANOVA. *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Holly Hammond for her close editing of the manuscript. We also thank Tam How, Brandy Edenfield and Gregory Kennedy for their technical support. This work was funded in part by NIH grant CA104505 (JAC and CGW), Dr. Ellis and Dona Brunton Rare Cancer Research Fund (JAC), NIH grant CA106307 (GCB) and a generous gift from Susan A. Olde, OBE.

Abbreviations

- ccRCC

clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- TβRIII

type III transforming growth factor beta receptor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- HDAC

histone deacetylase inhibitor

- TSA

trichostatin A

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Chakravarthy D, Green AR, Green VL, Kerin MJ, Speirs V. Expression and secretion of TGF-beta isoforms and expression of TGF-beta-receptors I, II and III in normal and neoplastic human breast. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:187–94. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S, Ranger-Moore J, Bowden TG. Differential inhibition of UVB-induced AP-1 and NF-kappaB transactivation by components of the jun bZIP domain. Mol Carcinog. 2005;43:108–16. doi: 10.1002/mc.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copland JA, Luxon BA, Ajani L, Maity T, Campagnaro E, Guo H, et al. Genomic profiling identifies alterations in TGFbeta signaling through loss of TGFbeta receptor expression in human renal cell carcinogenesis and progression. Oncogene. 2003;22:8053–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copland JA, Marlow LA, Kurakata S, Fujiwara K, Wong AK, Kreinest PA, et al. Novel high-affinity PPARgamma agonist alone and in combination with paclitaxel inhibits human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma tumor growth via p21WAF1/CIP1. Oncogene. 2006;25:2304–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, How T, Kirkbride KC, Gordon KJ, Lee JD, Hempel N, et al. The type III TGF-beta receptor suppresses breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:206–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI29293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RL, Blobe GC. Role of Transforming Growth Factor Beta in Human Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2078–2093. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger EC, Turley RS, Dong M, How T, Fields TA, Blobe GC. T{beta}RIII suppresses non-small cell lung cancer invasiveness and tumorigenicity. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:528–535. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio P, Ciarmela P, Reis FM, Toti P, Galleri L, Santopietro R, et al. Inhibin {alpha}-subunit and the inhibin coreceptor betaglycan are downregulated in endometrial carcinoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:277–284. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KJ, Dong M, Chislock EM, Fields TA, Blobe GC. Loss of type III transforming growth factor {beta} receptor expression increases motility and invasiveness associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition during pancreatic cancer progression. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:252–262. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote D, Souabni A, Busslinger M, Bouchard M. Pax 2/8-regulated Gata 3 expression is necessary for morphogenesis and guidance of the nephric duct in the developing kidney. Development. 2006;133:53–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.02184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbinas A, Berberat PO, Dambrauskas Z, Giese T, Giese N, Autschbach F, et al. Aberrant gata-3 expression in human pancreatic cancer. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:161–9. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6626.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumz ML, Zou H, Kreinest PA, Childs AC, Belmonte LS, LeGrand SN, et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 loss contributes to tumor phenotype of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4740–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel N, How T, Cooper SJ, Green TR, Dong M, Copland JA, et al. Expression of the type III TGF-beta receptor is negatively regulated by TGF-beta. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:905–12. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel N, How T, Dong M, Murphy SK, Fields TA, Blobe GC. Loss of Betaglycan Expression in Ovarian Cancer: Role in Motility and Invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5231–5238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho IC, Pai SY. GATA-3 - not just for Th2 cells anymore. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:15–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros-Mehr H, Bechis SK, Slorach EM, Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Ewald AJ, et al. GATA-3 links tumor differentiation and dissemination in a luminal breast cancer model. Cancer Cell. 2008a;13:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros-Mehr H, Kim JW, Bechis SK, Werb Z. GATA-3 and the regulation of the mammary luminal cell fate. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008b;20:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros-Mehr H, Slorach EM, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. GATA-3 Maintains the Differentiation of the Luminal Cell Fate in the Mammary Gland. Cell. 2006;127:1041–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labastie MC, Catala M, Gregoire JM, Peault B. The GATA-3 gene is expressed during human kidney embryogenesis. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1597–603. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Casillas F, Riquelme C, Perez-Kato Y, Ponce-Castaneda MV, Osses N, Esparza-Lopez J, et al. Betaglycan expression is transcriptionally up-regulated during skeletal muscle differentiation. Cloning of murine betaglycan gene promoter and its modulation by MyoD, retinoic acid, and transforming growth factor-beta. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:382–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208520200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulis V, Maity T, Zhang XY, Cooper SJ, Copland JA, Wood CG. Type III transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor mediates apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma independent of the canonical TGF-beta signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5722–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy TL, Pham TH, Knoll BI, Centrella M. Prostaglandin E2 increases transforming growth factor-beta type III receptor expression through CCAAT enhancer-binding protein delta in osteoblasts. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2713–24. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra R, Varambally S, Ding L, Shen R, Sabel MS, Ghosh D, et al. Identification of GATA3 as a Breast Cancer Prognostic Marker by Global Gene Expression Meta-analysis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11259–11264. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2530–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mythreye K, Blobe GC. The type III TGF-beta receptor regulates epithelial and cancer cell migration through beta-arrestin2-mediated activation of Cdc42. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8221–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nima Sharifi EMHBTKWLF. TGFBR3 loss and consequences in prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2007;67:301–311. doi: 10.1002/pros.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Belldegrun AS. The changing natural history of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2001;166:1611–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenvers KL, Tursky ML, Harder KW, Kountouri N, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Grail D, et al. Heart and Liver Defects and Reduced Transforming Growth Factor {beta}2 Sensitivity in Transforming Growth Factor {beta} Type III Receptor-Deficient Embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4371–4385. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4371-4385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares TS, Nanus D, Yang XJ, Gudas LJ. Gene microarray analysis of human renal cell carcinoma: the effects of HDAC inhibition and retinoid treatment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1607–18. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley RS, Finger EC, Hempel N, How T, Fields TA, Blobe GC. The type III transforming growth factor-beta receptor as a novel tumor suppressor gene in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1090–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Esch H, Groenen P, Nesbit MA, Schuffenhauer S, Lichtner P, Vanderlinden G, et al. GATA3 haplo-insufficiency causes human HDR syndrome. Nature. 2000;406:419–22. doi: 10.1038/35019088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CG. Multimodal Approaches in the Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Combining Surgery and Systemic Therapies to Improve Patient Outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:697s–702. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You HJ, How T, Blobe GC. The type III transforming growth factor-beta receptor negatively regulates nuclear factor kappa B signaling through its interaction with beta-arrestin2. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1281–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]