Abstract

The fowl pox vector expressing the tumor associated antigens MUC1 and CEA in the context of costimulatory molecules (rF-PANVAC) has shown promise as a tumor vaccine. However, vaccine mediated expansion of suppressor T cell populations may blunt clinical efficacy. We characterized the cellular immune response induced by ex-vivo dendritic cells (DCs) transduced with (rF)-PANVAC. Consistent with the functional characteristics of potent antigen presenting cells, rF-PANVAC-DCs demonstrated strong expression of MUC1 and CEA and costimulatory molecules, CD80, CD86, and CD83; decreased levels of phosphorylated STAT3, and increased levels of Tyk2, JAK2 and STAT1. rF-PANVAC-DCs stimulated expansion of tumor antigen specific T cells with potent cytolytic capacity. However, rF-PANVAC transduced DCs also induced the concurrent expansion of FOXP3 expressing CD4+CD25+high regulatory T cells (Tregs) that inhibited T cell activation. Moreover, Tregs expressed high levels of Th2 cytokines (IL-10, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) together with phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT6. In contrast, the vaccine expanded Treg population expressed high levels of Th1 cytokines IL-2 and IFNγ and the proinflammatory RORγt and IL-17A suggesting that these cells may share effector functions with conventional TH17 T cells. These data suggest that Tregs expanded by rF-PANVAC-DCs, exhibit immunosuppressive properties potentially mediated by Th2 cytokines, but simultaneous expression of Th1 and Th17 associated factors suggests a high degree of plasticity.

Introduction

Tumor cells evade host derived immune surveillance mechanisms through ineffective antigen presentation and the creation of an immunosuppressive milieu that inhibits T cell function. A major area of investigation is the development of cancer vaccines to educate effector cell populations to recognize and eliminate malignant cells. Viral based strategies have been developed in an effort to introduce tumor specific antigen into antigen presenting cells in the context of viral mediated inflammatory signals. A promising strategy involves the use of modified pox viral vectors that are incapable of in vivo replication and contain transgenes encoding for tumor associated antigens (1). When administered directly, these vectors may be taken up by native antigen presenting cells such as DCs and stimulate innate immune mechanisms that amplify DC mediated responses. In animal models, vaccination with attenuated vaccinia or fowl pox vectors encoding for PSA, CEA, or MUC1 results in the development of anti-tumor immunity (2). While cellular and humoral anti-tumor immune responses have been observed following vaccination with attenuated vaccinia, host antiviral responses limit their durability. In contrast, fowl pox vectors do not induce strong anti-viral immunity (1). As such, a prime/boost strategy involving sequential vaccination with vaccinia and fowl pox vectors, respectively has been shown to generate more durable antigen specific responses(3). In addition, insertion of genes coding for the costimulatory and adhesion molecules, CD80 (B7.1), CD54 (ICAM-1) and CD58 (LFA-3) (designated TRICOM) and the ligand binding 4-1BB further enhances immunologic response (4). In clinical studies, vaccination with pox viruses expressing tumor associated antigens has resulted in immunologic responses in a subset of patients (5–6). While patients exhibiting immunologic response had improved long term outcomes, expansion of tumor antigen specific lymphocytes was not associated with disease regression and ultimately the clinical impact of vaccination was not clearly established.

Tumor cells induce an immunosuppressive environment that limits vaccine efficacy. As such, understanding the interaction between virally transduced DCs and reactive T cell populations in this context is crucial to assess their potency as cancer vaccines. Previous studies have demonstrated that introduction of tumor associated antigens in the context of viral infection is associated with stimulation of innate immunity via toll like receptor (TLR) pathways, enhancement of DC function and production of a more effective anti-tumor response (7). However, other studies have demonstrated that viral infection of DCs may inhibit the capacity of DCs to effectively present antigens (8). Activation via Toll-like receptor signaling pathways results in transcription of type I IFN genes and proinflammatory cytokine genes such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 (9). Stimulation of human TLR7, for instance, induces IFN-α from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) important for innate antiviral immunity and the development of adaptive immunity, whereas it induces IL-12 from myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs), associated with the induction of a Th1 response (10). Use of TLR agonists with dendritic cell based vaccines therefore has the potential of enhancing polarization of T cell responses towards a Th1 cytokine profile leading to more robust effector T cell functions.

Immunologic response is defined by the presence of T cell subsets that may exert a pro-inflammatory or inhibitory effect (11). Vaccine efficacy is dependent on the induction of antigen specific T cells with an activated phenotype and the relative depletion of inhibitory elements that suppress primary T cell activation (12). In addition, long term immunity is dependent on the development of a central memory T cell response (13). Effective cellular immunity is classically associated with the relative expansion of Th1 cells that express IL-2 and IFNγ (11). Th17 cells have also been shown to express pro-inflammatory cytokines and contribute to immune mediated responses (14). In contrast, Th2 cells express suppressive factors such as IL-10, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-13 (11). Regulatory T cells play a central role in tumor mediated tolerance and evasion of host immunity (15). They are potent inhibitors of primary T cell activation and are defined by expression of FOXP3, high levels of CD25 expression, and low to absent expression of CD127 (16). DC based vaccines have been shown to paradoxically expand regulatory T cell populations that potentially blunt vaccine response (17).

Signaling via STAT related pathways plays a key role in polarizing DC and T cells towards an activated or inhibitory phenotype. Signaling via the STAT1 pathway induces DC maturation, enhanced antigen presenting capacity, and up-regulation of IL-12Rb2 on T cells resulting in greater responsiveness to IL-12 (18). Expression of Tyk2, a JAK kinase, is crucial for DC production of Th1-promoting cytokines such as IL-12 and IFNγ (19). In contrast, activation of STAT3 and STAT6 by Th2 cytokines, such as IL-6, IL4, and IL-13, promotes the polarization of T cells towards a Th2 phenotype (20). Phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT6 has also been associated with the suppression of effector cell function and the expansion of regulatory T cells (21). Th17 cells represent a subset of CD4+ T helper cells that are characterized by the expression of IL-17A and have recently been defined as a unique subset of pro-inflammatory helper cells whose development is associated with the induction of retinoicacid receptor-related orphan receptor γ-T (RORγt) (22). The potential connection between regulatory and Th17 cells populations is emphasized by the role of STAT3, IL-6 and TGF-β in the development of each population.

In the present study, we demonstrated that rF-PANVAC transduced DCs express the transgenes MUC1, CEA and co-stimulatory molecules in the context of increased levels of Tyk2, JAK2 and STAT1, necessary for the stimulation of Th1 T cells. Consistent with these findings, rF-PANVAC DCs elicit the expansion of activated T cells with anti-tumor cytolytic capacity. As seen in other vaccine models, rF-PANVAC DCs concomitantly induce the expansion of CD4+CD25+highFOXP3+ Tregs that blunt primary vaccine mediated responses However, further analysis of the Treg population revealed a complex cytokine profile that included both Th2 as well as Th1/Th17 derived factors consistent with the potential for immunosuppressive and pro-inflammatory phenotype. Taken together, our observations demonstrate rF-PANVAC DCs elicit a complex response that may exhibit considerable plasticity potentially dependent on the tumor microenvironment.

Materials and Methods

Monoclonal antibodies, reagents and cell culture media

Antibodies used for flow cytometric analysis included mouse PE and FITC conjugated anti-human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against HLA-DR, CD14, CD80, CD83, CEA, CD4, CD25, STAT3 (Y705) and STAT6 (Y641) and matching isotype controls (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA); PE and FITC conjugated mouse anti-human mAbs against CD4, CD69, CD8, and matching isotype controls (BD PharMingen); Monoclonal antibody DF3 (anti-MUC1 N-ter)(23); Anti-human CD4 and CD25TC (tricolor)-conjugated, PE-conjugated anti-human mAbs for IL-10, and IFN-γ, and their respective matching isotype controls (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); PE-conjugated mouse anti-human mAb CCR7, CCR4 and 62L, anti-human mAbs for Perforin, Granzyme B, IL-17A, FOXP3 and RORγt and matching isotype controls and intracellular staining kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA); FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). Recombinant human cytokines used for DC generation were GM-CSF (Berlex, Wayne/Montville, NJ), IL-4, TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). TLR7/8 (MM03) agonist was supplied by 3M Pharmaceuticals (St.Paul, MN). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 culture media containing 2 mmol/l L-glutamine (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) and supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% human AB male serum (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Mediatech) (referred to as complete media). Opti-MEM media was purchased from Gibco BRL (Invitrogen)

Generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DCs)

DCs were generated from PBMCs isolated from leukopaks obtained from normal donors as previously described (24). The enriched adherent fraction obtained from PBMNCs wascultured for 5 days in complete medium containing GM-CSF (1000 U/ml) and IL-4 (1000 U/ml) to generate immature DCs. To induce maturation, DCs were cultured for an additional 48 h in the presence of TNFα (25 ng/ml). In some experiments, 5 day cultured DCs were also exposed to TLR7/8 agonist (10 ug/ml) at the time of maturation.

Recombinant virus and infection of monocyte derived DCs with rF-PANVAC

Recombinant poxvirus vector (rF)-CEA(6)/MUC1(L93)/TRICOM (rF-CEA/MUC1/TRICOM also designated as rF-PANVAC) encodes the human CEA MUC1 gene and the genes for the human costimulatory molecules B7-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1),and the leukocyte function-associated antigen-3 (LFA-3) (25) (formerly manufactured by Therion Biologics Corp (Cambridge, MA) in collaboration with the Laboratory of Tumor Immunology and Biology, NCI). rF-PANVAC was supplied at viral concentration titer of 7.9×109 plaque-forming units/ml formulated in PBS containing 10% glycerol. Non-recombinant wild-type fowlpox virus was designated as FP-WT and used a control vector. DCs were transduced with 4 × 107 plaque-forming units (pfu) per milliliter of rF-PANVAC (1). Immature DCs (1 × 106/ml) cultured for 5 days in GM-CSF/IL-4 were harvested washed twice in neat RPMI and incubated in 1 mL of Opti-MEM medium at 37°C with rF-PANVAC or controlavipox virus vector (FP-WT) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 40 pfu/cell. To induce maturation, transduced and untransduced DCs were cultured for 48 h in RPMI complete media, GM-CSF/IL-4 (each 1000 U/ml) and TNFα (25 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of TLR7/8 agonist. DCs transduced with either rF-PANVAC or FP-WT were designated as rF-PANVAC-DCs and FP-WT-DCs respectively.

Flow cytometric analysis of DCs populations

Transduced and nontransduced DCs were incubated with primary mouseanti-human mAbs directed against MUC1, CEA, CD80, CD54, CD58, CD83, HLA-DR and matching isotype controls, washed, and cultured with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 and analyzed using FACScan (BD Biosciences as previously described (24). For dual color analysis, both surface markers and intracellular cytokine analysis were labeled with directly conjugated antibodies and analyzed by bi-dimensional FACS analysis (24).

Flow cytometric analysis and proliferation of stimulated T cell populations

rF-PANVAC-DCs, FP-WT-DCs, and untransduced DCs were cocultured with autologous nonadherent cells in a ratio of 1:10 in a V-shaped 96-well tissue culture plates for 5–7 days. Prior to analysis, CD4+ T cells were positively selected by Miltenyi magnetic beads (>97% purity) as previously described (24). The percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells expressing CD69 and FOXP3 was quantified. As a marker for cytolytic capacity, expression of Granzyme B and Perforin by CD8+ cells was determined. Intracellular cytokine expression was assessed following a 4 hr incubation with GolgiPlug (1ug/ml). CD4+ T cells were selected, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution and thereafter subjected to intracellular staining with PE-conjugated anti-human TNFα, IFNγ, IL-10 or IL-2 or a matched isotype control (24). Transduced and untransduced DCs were cocultured with autologous T cells at a ratio of 1:10, 1:30, 1:100, 1:300, and 1:1000 in 96-well V-bottom culture plates as described above, for 5 days at 37°C. T cell proliferation was determined by incorporation of [3H]thymidine (1μCi/well; 37kBq; NEN-DuPont) (24).

Immunoblot analysis of Jak2/STAT3, STAT1 and Tyk2 signaling in rF-PANVAC transduced DCs

3–5×106 DCs were lysed in cell lysis buffer and prepared for western blotting as previously described (23). Briefly, equal amounts of protein were run on an SDS-PAGE gel, followed by transfer onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was immunoblotted overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against: phospho-STAT1, phospho-STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology), STAT1, STAT3, JAK2, Tyk2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and MUC1 (Neomarkers). To confirm equal loading, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with antibody against β-actin (Sigma). The immune complexes were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) (23).

Determination of antigen specific T cells by Tetramer staining

Following 5 days of stimulation with the DC populations, CD8+ MUC1 tetramer+ T cells were identified using PE-labeledHLA-A*0201+ iTAg MHC class I human tetramer complexes (BeckmanCoulter) composed of four HLA MHC class 1 molecules each bound to MUC1-specific epitopes M1.2 (MUC112–20) LLLLTVLTV (26). An A*0201 irrelevant peptide MHC class I tetramer was used as a negative control (24).

Assay for evaluation of Cytolytic Activity

To assess the cell-mediated cytotoxicity, we utilized the fluorescently based GranToxLux assay kit system (OncoImmune, Gaithersburg, MD). Autologous T cells were harvested after 5 days coculture with rF-PANVAC-DCs or untransduced DCs and enriched using nylon wool columns (24). Target cells consisted of autologous DCs transduced with rF-PANVAC. Transduced or untransduced DC target cells were incubated in APC labeled Medium T (1μL of reconstituted TFL4 in PBS at 1:3000 ratio) at 2×106 cells/ml for 45 minutes at 37°C, and thereafter washed in PBS. Stimulated T cells were washed in PBS and co-incubated in a 1:5 ratio with autologous fluorescently labeled (red) target cells in the presence of a fluorogenic Granzyme B substrate for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) for expression of Granzyme B. In the assay, cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate by Granzyme B results in an increase of green fluorescence in the target cells that experience Granzyme B activity in them.

Cytokine secretion into culture supernatants following DC stimulation of autologous non-adherent cells

The profile of secreted cytokines in the culture supernatant by T cells stimulated with rF-PANVAC-DCs or untransduced DC for 5 days was determined using the Bio-Rad Bioplex system from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) in combination with multiplex cytokine and chemokine kits, accordingly to the manufacturer’s instructions and specifications. Supernatants were collected before cell harvest and frozen at −80°C until analyzed. Cytokine kits of up to 17 cytokines and chemokines were used. The cytokines measured were: IL-1a, IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IL-13,IL-15, IL-17, G-CSF, GM-CSF, MCP-1, MIP-1b, IFNγ, and TNFα.

Phenotypic and functional characterization of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high T cells

rF-PANVAC-DCs and untransduced DCs were cocultured with autologous nonadherent cells in a ratio of 1:10 in V-shaped tissue culture plates. In an effort to segregate activated and regulatory T cell populations based on the expression of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low andCD4+CD25+high, CD4+ T cells were positively selected (>97% purity) from the pooled cells and sorted using a BD FACSAria cell sorting instrument (BD Biosciences) as previously described and stained for intracellular expression of FOXP3, RORγt, IL-17A, STAT3 (pY705), STAT6 (pY641) (24). In a separate set of experiments, CD4+CD25+high T cells were segregated by gating and analyzed for the dual expression of FOXP3 and IL-17. Cell lysates of T cell subpopulations were generated by sonication and analyzed for the expression of cytokines in the Bioplex system. Functional analysis of the CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, or CD4+CD25+high T cells were performed by assessing their capacity to suppress primary stimulation of T cells with rF-PANVAC-DCs.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

In separate sets of experiments, total RNA was isolated from purified CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high population of sorted cells, enriched T cells activated for 48h using CD3/CD28 antibodies and from MCF7 cells using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was converted to cDNA using the One-Step RT-PCR kit with Platinum Taq using the SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with random primers, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR primers were designed based on the sequences reported in GenBank with the Primer Express software version 1.2 (Applied Biosystems) as follows: FOXP3 forward- 5′-CAC CTG GCT GGG AAA ATG G-3′; FOXP3 reverse- 5′-GGA GCC CTT GTC GGA TGA T-3′; PD1 forward 5′-CCG CTT CCA GAT CAT ACA G-3′; PD1 reverse 5′-CTC TGG CCT CTG ACA TAC TTG-3′; human MUC1 forward, 5′-TAC CGA TCG TAG CCC CTA TG- 3′; human MUC1 reverse 5′-CCT GTT TGG GCT GGT GAG- 3′; GAPDH forward- 5′-CAA AGT TGT CAT GGA TGA CC-3′ ; GAPDH reverse- 5′-CCA TGG AGA AGG CTG GGG-3′. PCR amplification of the housekeeping gene encoding GAPDH was performed for each sample as control.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. For comparisons, Student’s t test was used and values of p < 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

rF-PANVAC-DCs express MUC, CEA, and costimulatory molecules

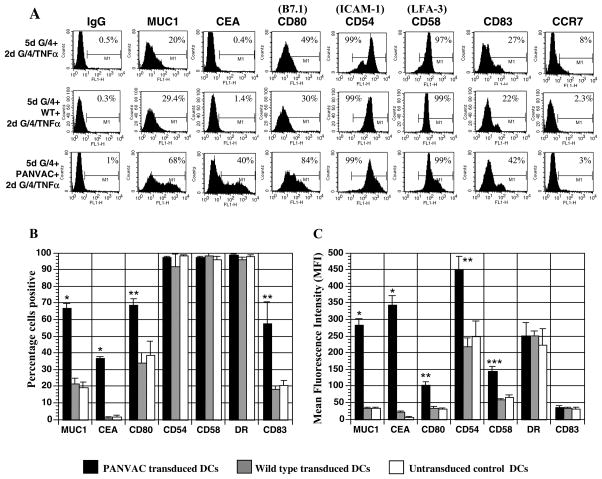

Following transduction with rF-PANVAC, MUC1 and CEA was expressed by 66.9% (SEM±2.7; n=13) and 36.7% (SEM±1.1; n=4) of the DC preparation with a mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of 284.9 (SEM±18.5) and 342.8 (SEM±29.5), respectively. In contrast, FP-WT-DCs or untransduced mature DCs did not express CEA and demonstrated only minimal levels of MUC1 (Figure 1A-C). Transduction with rF-PANVAC resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of DCs expressing CD80 (69% SEM ±8.6; MFI 102 SEM ±9.6) compared to FP-WT-DCs (34.3% SEM±5.2; MFI 34.4 SEM ±5.2) or untransduced DCs (38.9% SEM±8.3 MFI 31 SEM ±2.6) (Figure 1B). Expression of CD54 and CD58 was seen in untransduced DCs but were further upregulated following transduction with rF-PANVAC (Figure 1C). rF-PANVAC-DCs expressed increased levels of the maturation marker CD83 (57.5% ) as compared to 18.2% and 20.5% in FP-WT-DCs and untransduced DCs respectively (p<0.05). These findings demonstrate that transduction with rF-PANVAC resulted in increased expression of the tumor antigens and costimulatory molecules introduced by the viral vector and facilitated maturation of the transduced DC population. There were no significant differences observed in the percentage of surface markers examined in FP-WT-DCs as compared to untransduced mature DCs (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Expression of MUC1, CEA, costimulatory, adhesion and maturation markers on fowlpox transduced and untransduced dendritic cells.

(A) Expression of, MUC1, CEA, CD80 (B7.1), CD54 ICAM-1), CD58 (LFA-3), and CD83 by rF-PANVAC-DCs, FP-WT-DCs and untransduced DCs was quantified by flow cytometric analysis. Depicted is a representative FACS analysis for each set. (B and C) Mean percentage (± SEM) of cells expressing the indicated marker and the corresponding mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is presented. (* p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.05).

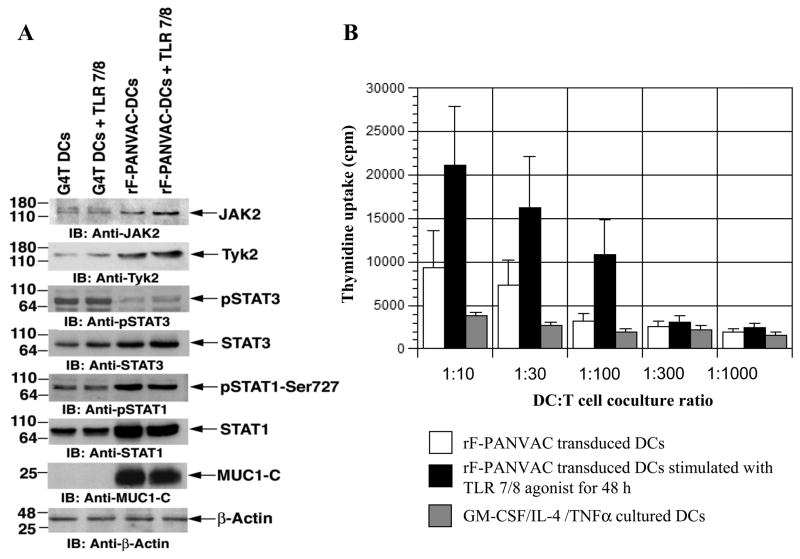

Jak2/STAT3, STAT1 and Tyk2 signaling in rF-PANVAC transduced dendritic cells

To further assess the impact of PANVAC transduction on DC polarization and function, we measured the effect on Jak2/Tyk 2 and the STAT1 signaling pathways that have been shown to be critical for DC maturation and antigen presentation (21, 27). Transduction with rF-PANVAC was associated with increased levels of JAK2, Tyk2, and STAT1 consistent with the promotion of DC maturation (Figure 2A). Consistent with these findings, transduction with rF-PANVAC resulted in decreased levels of phosphorylated STAT3 as an inhibitory pathway (Figure 2A). In an autologous coculture setting, rF-PANVAC-DCs stimulated higher levels of T cell proliferation as compared to untransduced DCs which was further augmented by coculture with a TLR7/8 agonist (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Expression of Tyk2, JAK2, STAT3, STAT1 proteins and autologous T cell proliferative response to rF-PANVAC-DCs and untranduced DCs.

(A) rF-PANVAC-DCs differentiated in the presence or absence of a TLR7/8 agonist for 48 h were harvested, lysed and underwent Western Blot analysis to assess expression of Tyk2, JAK2, STAT3, STAT1 proteins, the phosphorylated forms of STAT1 (pSTAT1) and STAT3 (pSTAT3) and MUC1-C. β-actin antibody was utilized as a loading control. Western blot analysis was also performed for untransduced DCs, untransduced DCs cultured with a TLR7/8 agonist. Depicted are representative results obtained from two independent experiments using DCs generated from different donors. G4T: GM-CSF/IL-4/TNFα cultured DCs; G4T DCs+TLR 7/8: GM-CSF/IL-4/TNFα cultured DCs stimulated for 48 h with TLR 7/8 agonist; rF-PANVAC-DCs: rF-PANVAC transduced DCs; rF-PANVAC-DCs+TLR7/8: rF-PANVAC transduced DCs stimulated for 48 h with TLR 7/8 agonist. (B) rF-PANVAC-DCs and untransduced DCs differentiated in the presence or absence of a TLR7/8 agonist were cocultured with enriched autologous T cells at the indicated DC:T cell ratios. T cell proliferation was determined after 5 days of coculture by incorporation of 3[H] Thymidine (1 μCi/well) added to cocultures 18 h prior to harvesting. T cell proliferation was measured as cpm. Bar graph data (mean cpm ± SEM) is representative of three separate experiments.

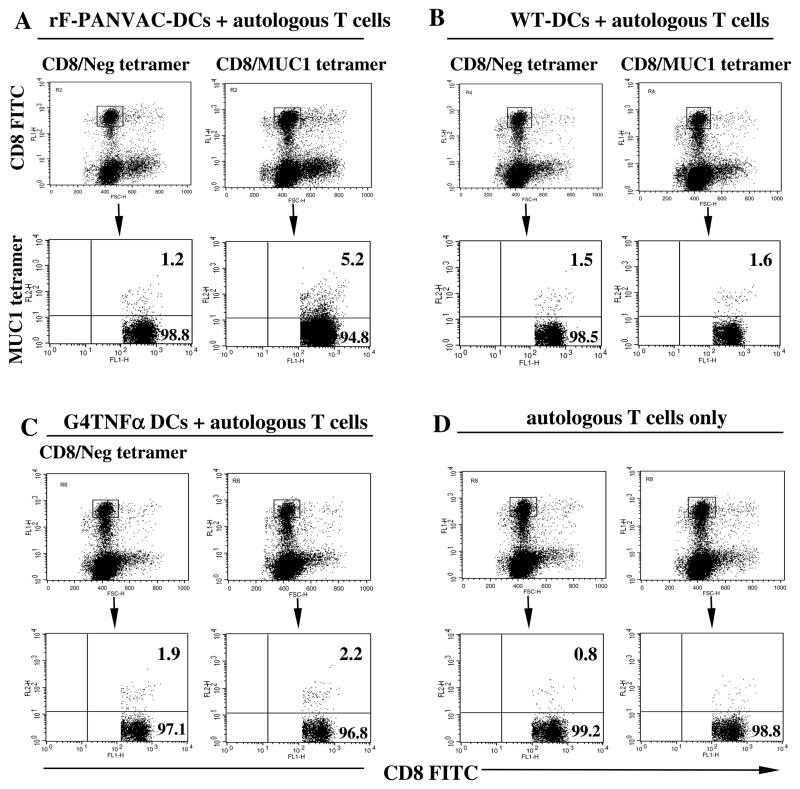

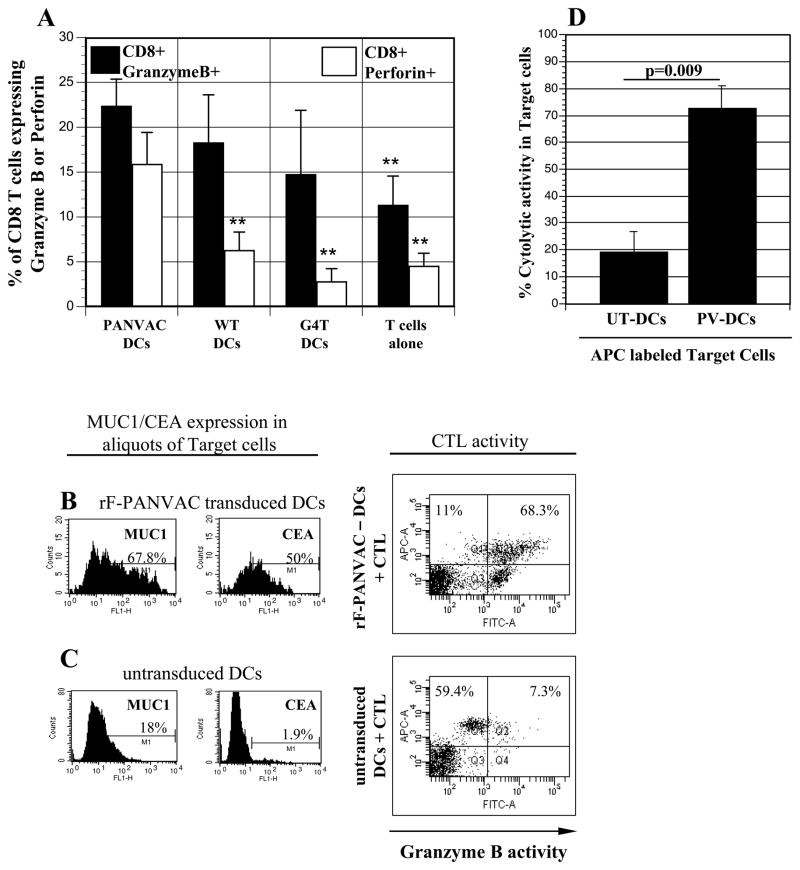

DCs transduced with rF-PANVAC stimulate the expansion of antigen specific T cells

rF-PANVAC-DCs induced the expansion of tumor antigen specific T cells as manifested by a significant increase in CD8+ T cells binding the MUC1 tetramer (Figure 3). In contrast, neither FP-WT-DCs (Figure 3B) nor untransduced DCs (Figure 3C) induced the expansion of MUC1 tetramer+ cells. We subsequently assessed the ability of rF-PANVAC-DCs to stimulate functionally competent cytotoxic T lymphocytes as determined by their expression of granzyme B and perforin, key elements in the cytolytic pathway. As compared to resting T cells or those stimulated by untransduced DCs, mean T cell expression of granzyme B was increased following stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs (Figure 4A). Similarly, a dramatic increase in perforin expression was noted in the T cell population stimulated by rF-PANVAC-DCs. These findings suggest that rF-PANVAC-DCs induce the expansion of tumor antigen specific T cells with cytolytic capacity. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity was quantified using cell-based fluorogenic cytotoxicity assay. Aliquots of the transduced DCs as target cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to verify expression of MUC1 and CEA (Figure 4B-C). Granzyme B activity was identified by an increase in the percentage of rF-PANVAC-DCs with green fluorescence in the upper right quadrant that represented dying, Granzyme B-positive target cells (Figure 4B-C). In a mean of three separate experiments, 72.7% (SEM±11.8%) of rF-PANVAC-DCs demonstrated Granzyme B activity as compared to 19.3% (SEM±7.5%) by untransduced DCs (p=0.009) (Figure 4D). This data demonstrates that rF-PANVAC-DCs induce and expand antigen specific CTLs with cytolytic capacity.

Figure 3. Expansion of CD8+MUC1 tetramer+ T cells following stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs.

(A–D) HLA*0201 autologous nonadherent cells were co-cultured with rF-PANVAC-DCs, FP-WT-DCs, or untransduced DCs for five days. CD8+ T cells were analyzed for binding with the MUC1 tetramer or a control tetramer. Unstimulated enriched autologous T cells were analyzed in parallel as controls. Numbers in the upper quadrant of the indicated bi-dimensional dot plots represent the percentage of dual positive CD8+ MUC1 tetramer+ T cells. Dot blot analysis shows representative results obtained from two independent experiments using DCs generated from different donors.

Figure 4. Cytolytic capacity of expanded T cells following autolgous T cell coculture with rF-PANVAC-DCs.

(A) Autologous non-adherent cells were cocultured for 5 days with rF-PANVAC-DCs, rF-WT-DCs, or untransduced DCs at a T:DC ratio of 10:1. T cells alone were cultured and analyzed in parallel. The cells were harvested and CD4+ T cells were positively selected by magnetic bead separation. Bar graphs depicting the mean percentage (± SEM) of CD8+T cells expressing Granzyme B or Perforin from 5 separate experiments. (B–C) Autologous T cells were cultured with rF-PANVAC-DCs or untransduced DCs for 5 days and thereafter enriched using nylon wool columns. rF-PANVAC-DCs and untransduced DCs autologous to enriched T cells were prepared separately and used as target cells in a cell-based fluorogenic cytotoxicity assay. An aliquot of transduced and untransduced DCs were examined for the expression of MUC1 and CEA as shown in the left panel of the figure. Target cells were labeled by a fluorescent dye projecting in the FL-3 channel and co-incubated with enriched autologous T cells in a 5:1 ratio in the presence of a fluorogenic granzyme B substrate. Cell-mediated cytotoxicity results in the uptake of granzyme B by target cells and is detected by the presence of the fluorogenic granzyme B substrate in the FL-1 channel (upper right quadrant) as shown in this representative plot. The proportion of transduced or untransduced DCs targeted by autologous CTLs is calculated as the number of cells in the upper right quadrant divided by the sum of upper left and upper right quadrants. (D) The histograms depict the mean (± SEM) cytolytic activity of three separate experiments of transduced and untransduced DCs by expanded autologous T cells. UT-DCs: untransduced DCs; PV-DCs: panvac transduced DCs (rF-PANVAC-DCs). (** p < 0.01 as compared to rF-PANVAC-DCs).

Expansion of activated and regulatory T cells by rF-PANVAC transduced DCs

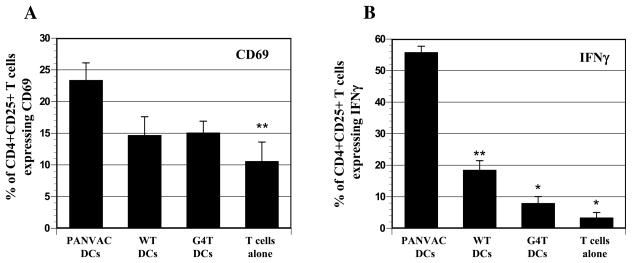

The activation marker, CD69, was observed in a greater number of T cells stimulated by rF-PANVAC-DCs (mean 23.4%, SEM±2.7, n=5) as compared to untransduced (mean 15.1%, SEM±1.8, n=5) DCs (Figure 5A). In contrast, CD69 expression was not increased following stimulation with FP-WT-DCs, suggesting that the expansion of activated T cells requires the presence of the transgenes contained in rF-PANVAC (Figure 5A). Consistent with the expansion of activated T cells, stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs resulted in an increase in CD4+CD25+ T cells expressing IFNγ (Mean 55.8%; SEM±1.9; n=3). In contrast, only a minority of T cells (8%; SEM±2.0; n=3) expressed IFNγ following stimulation with untransduced DCs (Figure 5B). We then quantified Th1 and Th2 cytokines in the supernatant collected after a 5 day stimulation period. As compared to T cells stimulated by untransduced autologous DCs, stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs resulted in a 15.5, 1.75, and 3 fold increase in IFNγ, IL-2, and TNFα expression, respectively (Table 1). Of note, a rise in Th2 cytokines was also observed. As compared to T cells cocultured with untransduced DCs, a mean fold increase of 3.9, 3.4, 2.4, 1.6, and 2.8 was observed for IL-10, IL4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-13, respectively. These data suggest that rF-PANVAC-DCs induce a mixed Th1 and Th2 response and the expression of both pro-inflammatory and inhibitory cytokines.

Figure 5. Expression of CD69 and IFNγ by CD4+CD25+ T cells following stimulation with transduced and untransduced DCs.

(A) The histograms depict the mean percentage of CD4+CD25+ T cells that coexpress the activation marker, CD69 from 5 separate experiments (± SEM). (B) Positively selected CD4+ T cells were stained with CD25-FITC, fixed and permeabilized followed by incubation with PE-conjugated IFNγ or matching isotype controls and analyzed by bi-dimensional flow cytometry. Bar graph shows the mean percentage (± SEM) of CD4+CD25+ T cells expressing IFNγ from 5 separate experiments. (* p<0.001; ** p<0.01 as compared to PANVAC transduced DCs).

Table I.

Cytokine concentration (pg/ml) in culture supernatants of transduced and untransduced DCs cocultured with autologous non-adherent cells following a five day culture period.

| G4T-DCs coculture | rF-PANVAC-DCs coculture | rF-PANVAC-DCs + TLR7/8 coculture | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | 595 ± 117 (n=7) | 2345 ± 1023 (n=7) | 2731 ± 1578 (n=7) |

| IL-12(p70) | 105 ± 14 (n=7) | 331 ± 162 (n=7) | 139 ± 8 (n=7) |

| IFNγ | 202 ± 41 (n=7) | 3141 ± 917 (n=7) | 3112 ± 1536 (n=7) |

| IL-2 | 1265 ± 929 (n=7) | 2208 ± 608 (n=7) | 1891 ± 601 (n=7) |

| IL-4 | 268 ± 49 (n=7) | 911 ± 188 (n=7) | 804 ± 202 (n=7) |

| TNFα | 1094 ± 441 (n=7) | 3223 ± 1759 (n=7) | 1647 ± 454 (n=7) |

| IL-5 | 8399 ± 4324 (n=7) | 19925 ± 3527 (n=7) | 20490 ± 1272 (n=7) |

| IL-6 | 13004 ± 2643 (n=7) | 20962 ± 1175 (n=7) | 22113 ± 1481 (n=7) |

| IL-13 | 6514 ± 3627 (n=7) | 17931 ± 3568 (n=7) | 15677 ± 3167 (n=7) |

| IL-17 | 489 ± 96 (n=7) | 934 ± 114 (n=7) | 778 ± 129 (n=7) |

| MCP-1 | 72 ± 39 (n=7) | 148 ± 34 (n=7) | 171 ± 194 (n=7) |

Transduced and untransduced DCs were cocultured with autologous non-adherent cells for a 5 day culture period. Culture supernatants were harvested and analyzed to determine for Th1 and Th2 cytokine profile. G4T-DCs: GM-CSF/IL-4/TNFα cultured DCs; rF-PANVAC-DCs : rF-PANVAC transduced DCs; rF-PANVAC-DCs + TLR 7/8: rF-PANVAC transduced DCs followed by 48 hr stimulation with TLR7/8 agonist. Cytokine concentration (pg/ml) represents the mean (±SEM) of 7 separate experiments.

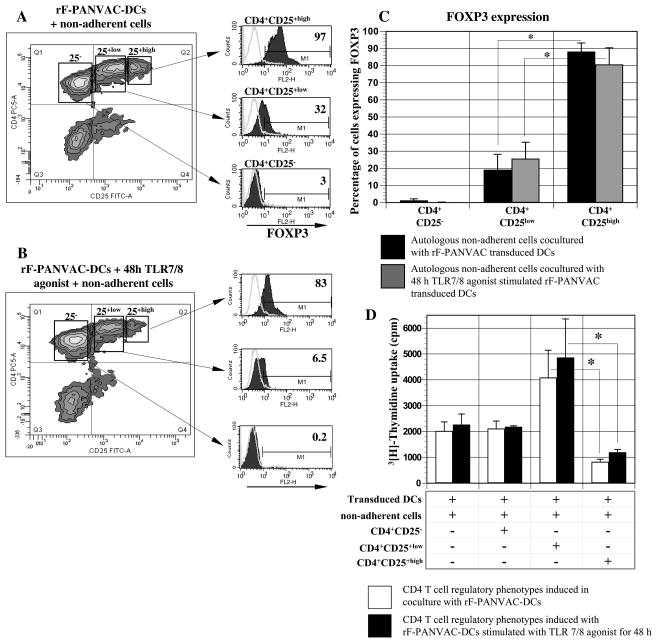

Coculture with rF-PANVAC-DCs induced the expansion of CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high cells. CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high fractions were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (24). CD4+CD25+high T cells demonstrated nearly uniform of FOXP3 expression (mean 88.2%, SEM±5.2, n=3) consistent with Tregs (Figure 6A-C). In contrast, only a minority of the CD4+CD25+low T cells expressed FOXP3, whereas FOXP3 expression was absent in the CD4+CD25− population. Consistent with a regulatory T cell phenotype, the CD4+CD25+high fraction inhibited the proliferation of T cells in response to transduced DCs. Exposure to the TLR7/8 agonist did not effect the ratio of CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high cells or the inhibitory characteristics of the latter population (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Expression of FOXP3 and suppressive function of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high T cells T cells stimulated by rF-PANVAC-DCs.

Autologous non-adherent cells were cocultured with rF-PANVAC-DCs or untransduced DCs in the presence or absence of TLR7/8 agonist at a T:DC ratio of 10:1. After 5 days of coculture, the cells were harvested and incubated with anti-CD4 TC and anti-CD25 FITC. (A & B) T cells were separated into CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high fractions by bi-dimensional FACS sorting as shown in representative dot plots. Cells then underwent intracellular staining for FOXP3. (C) Mean percentage (± SEM) of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high regulatory T cell phenotypes expressing FOXP3 from 3 separate experiments. (D) The capacity of the sorted T cell fractions to suppress T cell proliferation was then determined. rF-PANVAC transduced DCs and transduced DCs exposed to TLR7/8 agonist were cocultured with non-adherent autologous cells in the presence or absence of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, or CD4+CD25+high T cells in an overall DC:T cell ratio of 1:10. T cell proliferation was quantified after 4 days culture by uptake of [3H]Thymidine (1 μCi [0.037 MBq] per well) following overnight pulsing. Bar graph represents the mean cpm (±SEM) of 3 separate experiments. (* p <0.001).

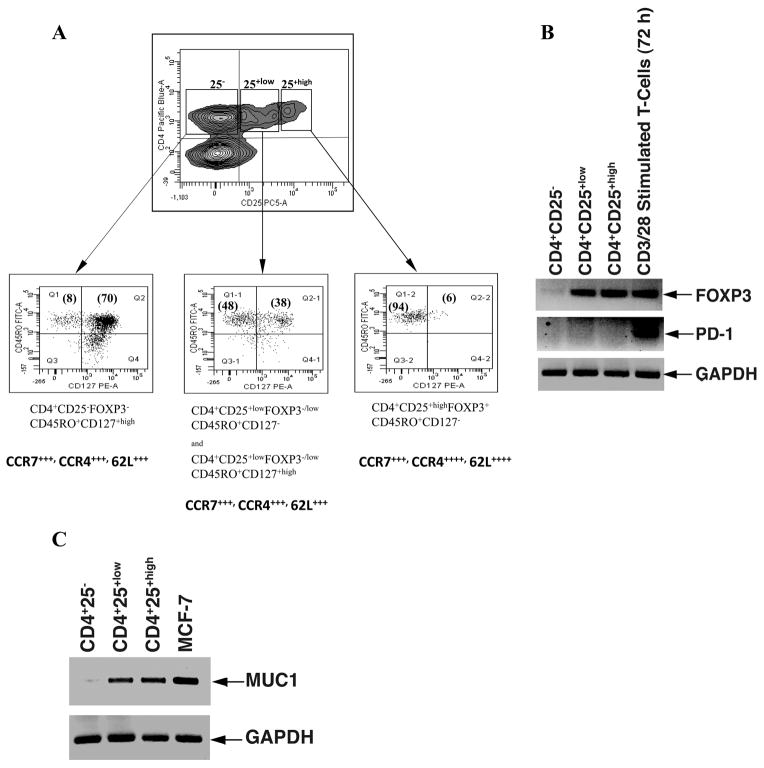

Tregs can also be differentiated by the expression of chemokine receptors presumably reflecting differences in homing. Chemokine receptor CCR4 has been shown to be involved in peripheral migration of T cells and is expressed on at least 20% of circulating CCR4+ CD4+ T cells representing CCR4+ regulatory T cells (CCR4+CD4+CD25+) that exert suppressive functions via the production of immunosuppressive cytokines (28–29). Moreover, CCR4+ Tregs have been shown to represent a memory phenotype (CD45RA−/RO+) and circulate between the periphery (30–31)and secondary lymphoid organs as demonstrated by the additional expression of homing markers CD62L and CCR7 (29). Following stimulation with rF-PANVAC DCs, the CD4+CD25+high fraction were predominantly of memory origin expressing CD45RO+, CCR7, CCR4, and CD62L, did not express CD127, and inhibited the proliferation of T cells in response to transduced DCs (Figure 7A) (16, 32). The CD4+CD25+low population consisted of a mixed population of both the CD127+high (48%) and CD127− (38%) cells (Figure 7A, middle panel) whereas the CD4+CD25− predominantly consisted of CD127+high expressing T cells (Figure 7A, left panel). In contrast to intracellular staining of FOXP3 in the CD4+CD25+high fraction, FOXP3 mRNA transcripts were detected both in the CD4+CD25+low and the CD4+CD25+high fractions, whereas no transcripts were detected in the CD4+CD25− population (Figure 7B). Programmed death-1 (PD-1) has recently been defined as molecule that serves as a negative costimulatory receptor on various cell types including T and B cells as well as myeloid derived cells (33). We decided to examine whether this molecule would be expressed at mRNA levels in the isolated CD4+CD25+high fraction and observed that no PD-1 mRNA transcripts were expressed in these cells (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Expression of CD127 and mRNA transcripts for FOXP3, PD-1 and MUC1 in CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high T cells.

rF-PANVAC-DCs were cocultured with autologous non-adherent cells for 5 days. Cells were harvested and labeled with anti-CD4 Pacific Blue and anti-CD25 PC5, anti-CD45RO FITC and anti-CD127 PE. CD4+ T cells were segregated into CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high fractions as shown in a representative dot plot. Each of the segregated populations of cells was isolated by gating as shown and further analyzed for the presence of CD45RO+ and CD127+ surface markers. In a separate set of experiments, T cells were harvested from the co-culture and labeled with anti-CD4 TC, anti-CD25 FITC, and anti-CCR7 PE, anti-CCR4 PE or anti-62L PE. (A) CD4+ T cells were segregated into three populations of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high and the percentage of these gated isolated cells positive for each of the chemokine and L-select in surface markers was determined. Dot blot analysis shows representative results obtained from two independent experiments using DCs generated from different donors. Numbers in parentheses in the dot plot quadrants indicate the percentage of dual positive cells for the appropriate surface markers. ++++ represents > 90% and +++ > 80% of the cells positive for the indicated markers. (B) RT-PCR for mRNA for FOXP3 and PD-1 and (C) MUC1 for each of the fractions of CD4+ T cells. Enriched T cells stimulated for 48h with CD3/CD28 antibodies was used as controls. MCF7 breast carcinoma cell line was used as positive control for MUC1 as shown. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments.

An immunoregulatory role has been postulated for MUC1 mucin expressed by activated T cells (34–35). It is possible that MUC1 mucin may act as an inhibitory co-receptor in T cells and also serve a role in lymphocyte trafficking due to its adhesion and/or anti-adhesion properties. We therefore, examined the presence of MUC1 mRNA transcripts in the CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low and the CD4+CD25+high fractions of sorted cells to determine whether expression of MUC1 correlated with the functional properties of the cells. We found that mRNA expression for MUC1 was most pronounced in the CD4+CD25+high population of cells in a similar fashion to that of FOXP3 expression (Figure 7C). Following stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs, an increase in IL-10, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-13 was observed, with a mean fold increase of 3.5, 5.3, 42.7, 2, and 25, respectively, as compared to untransduced DCs (Table 2). Of note, exposure to a TLR 7/8 agonist during the period of T cell stimulation abrogated the increase in the Th2 cytokines, IL-10, IL-5, IL-13, and the chemokine, MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattarctant protein-1) (36). Surprisingly, stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs also resulted in a significant rise of Th1 cytokines secreted by CD4+CD25+high T cells with a mean fold increase of 21, 5.3, and 11.5 for IFNγ, IL-2, and TNFα, respectively.

Table II.

Lysate cytokine concentration (pg/ml) in segregated populations of regulatory T cell

| CD4+CD25− | CD4+CD25+low | CD4+CD25+high | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 215 (± 7.8) | 653 (± 228.6) | 1542 (± 433.8) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 208 (± 2.1) | 408 (± 27.5) | 403 (± 77.3) |

| G4T DCs | 211 (± 6.9) | 274 (± 30.7) | 442 (± 57) |

|

| |||

| IFNγ | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 27.5 (± 0.8) | 138 (± 19) | 855 (± 173.3) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 29 (± 1.8) | 118 (± 3.8) | 473 (± 49.8) |

| G4T DCs | 27 (± 1.7) | 30 (± 4.4) | 40 (± 9.4) |

|

| |||

| IL-12(p70) | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 140 (± 13.6) | 247 (± 2.7) | 293 (± 11.2) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 131 (± 0.6) | 210 (± 38.2) | 257 (± 5) |

| G4T DCs | 138 (± 11.6) | 135 (± 19.1) | 135 (± 6.3) |

|

| |||

| IL-4 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 69 (± 3.3) | 178 (± 7.2) | 417 (± 26.5) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 55 (± 1.6) | 128 (± 14.8) | 189 (± 15.6) |

| G4T DCs | 63 (± 1.5) | 64 (± 0.9) | 79 (± 3.4) |

|

| |||

| IL-2 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 43 (± 1) | 986 (± 402) | 769 (± 214) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 36 (± 2.5) | 737 (± 143) | 452 (± 52.4) |

| G4T DCs | 47 (± 9.5) | 145 (± 61.8) | 143 (± 11.3) |

|

| |||

| TNFα | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 66 (± 15.5) | 759 (± 184) | 2192 (± 562) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 52 (± 2.4) | 516 (± 16.3) | 937 (± 149) |

| G4T DCs | 39 (± 7.5) | 76 (± 22.3) | 191 (± 12.7) |

|

| |||

| IL-5 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 14 (± 0.3) | 93.5 (± 42) | 4694 (± 1919) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 15.7 (± 0.9) | 31 (± 0.6) | 272 (± 18) |

| G4T DCs | 16.3 (± 1.5) | 19.2 (± 2.2) | 110 (± 39) |

|

| |||

| IL-6 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 123 (± 21.9) | 182 (± 20.5) | 201 (± 33.5) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 121 (± 8.1) | 174 (± 4.7) | 174 (± 7.4) |

| G4T DCs | 113 (± 32.8) | 148 (± 47.5) | 97 (± 5) |

|

| |||

| IL-7 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 107 (± 1.6) | 122 (± 5.8) | 128 (± 5.6) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 98 (± 2.1) | 122 (± 5.8) | 125 (± 2.2) |

| G4T DCs | 111 (± 4.1) | 88 ( ± 4.2) | 103 (± 13) |

|

| |||

| IL-8 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 103 (± 15.8) | 656 (± 261.8) | 1104 (± 74.6) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 83 (± 2.6) | 514 (± 5.8) | 1518 (± 125) |

| G4T DCs | 114 (± 3.4) | 1061 (± 89.8) | 732 (± 69) |

|

| |||

| IL-13 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 81.5 (± 10) | 340.3 (± 144) | 3459 (± 2576) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 68.3 (± 2.0) | 138 (± 1.7) | 500 (± 141) |

| G4T DCs | 81.3 (± 12.8) | 86.2 (± 24) | 140 (± 37) |

|

| |||

| IL-15 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 123 (± 0.7) | 134 (± 9.3) | 152 (± 13) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 109 (± 1.5) | 126 (± 11.8) | 135 (± 4.8) |

| G4T DCs | 114 (± 3.4) | 1061 (± 89.8) | 732 (± 69) |

|

| |||

| IL-17 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 196 (± 6) | 523 (± 56) | 855 (± 70) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 185 (± 2) | 481 (± 27) | 574 (± 5.7) |

| G4T DCs | 179 (± 3.8) | 200 (± 3.8) | 231 (± 24) |

|

| |||

| MCP-1 | |||

| rF-PANVAC- DCs | 240 (± 44.9) | 3501 (± 503) | 3109 (± 539) |

| rF-PANVAC- DCs+TLR 7/8 | 146 (± 6.1) | 920 (± 206) | 663 (± 191) |

| G4T DCs | 323 (± 50) | 1268 (± 541) | 1412 (± 99) |

Autologous non-adherent cells were cocultured with untransduced and transduced DCs for 5 days. Prior to harvest, the coculture wells were subjected to GolgiPlug treatment (1 μg/ml) for a period of 4–5 h. Cells were harvested, stained and segregated into the three populations of regulatory T cells by FACS sorting and sonicated to collect cell lysate for cytokine analysis as described in materials and methods. rF-PANVAC-DCs: rF-PANVAC transduced DCs; rF-PANVAC-DCs+TLR7/8: rF-PANVAC transduced DCs stimulated for 48 h with TLR 7/8 agonist; G4T DCs; GM-CSF/IL-4/TNFα cultured DCs. Concentration of cytokines (pg/ml) represents the mean (±SEM) of three separate experiments.

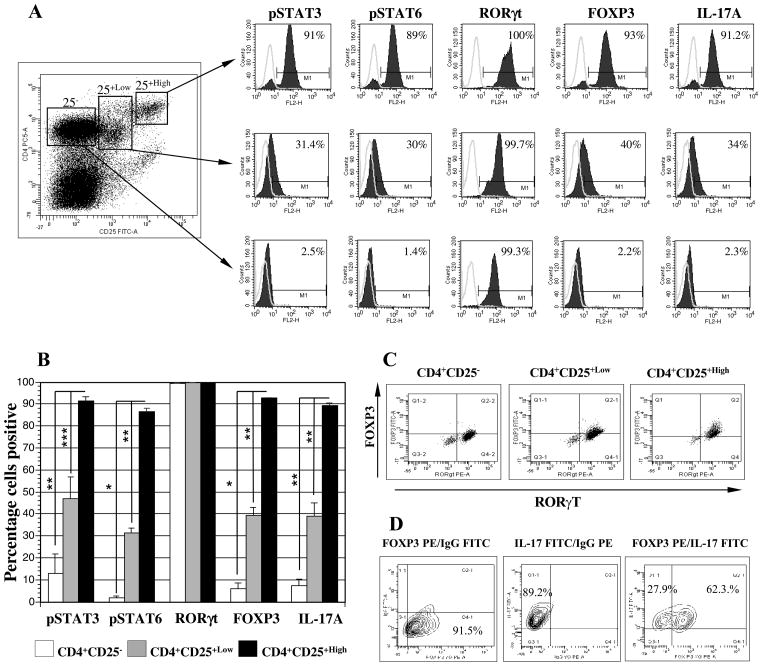

Expression of phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT6, RORγt, FOXP3 and IL-17A in segregated populations of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high T cells

STAT3 supports the expansion of Th2 cells and is critical for expression of IL-10, TGFβ and FOXP3 as mediators of Treg expansion (37–38). Similarly, STAT6 is upregulated by exposure to IL-4 and IL-13 and has been directly implicated in the development and survival of antigen specific CD4+CD25+highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells (39). Expression of phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) was observed in 91.5% (SEM: ±1.7; n=3), 47% (SEM: ±9.76; n=3), and 13.2 % (SEM: ±8.5; n=3) of the CD4+CD25+high T cells, the CD4+CD25+low (p=0.02), and the CD4+CD25− T cells (p<0.01), respectively (Figure 8A and 8B). Similarly, pSTAT6 was highly expressed in CD4+CD25+high T cells, (86.7%; SEM: ±1.3; n=3) as compared to CD4+CD25+low (31.5%; SEM: ±2.1; n=3, p<0.01) or the CD4+CD25− (1.97%; SEM: ±0.7; n=3, p=0.0002) T cells (Figure 8A and 8B).

Figure 8. Enhanced expression of phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT6 and RORγt, FOXP3 and IL-17A in isolated CD4+CD25+high regulatory T cells.

rF-PANVAC-DCs were cocultured with autologous non-adherent cells at a 1:10 ratio for 5 days. 3 h prior to harvesting, the cells were treated with 1ug/ml of GolgiPlug, after which the cells were harvested, labeled with anti-CD4 Pacific Blue and anti-CD25 PC5 and segregated into CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high fractions by FACS Aria sorting as shown in a representative dot plot. (A) Each of the segregated populations of CD4+ T cells were fixed, permeabilized and subjected to intracellular staining with the appropriate antibody and its matching isotype control and thereafter analyzed on a single FL2-H channel. Histogram peaks are depicted with an overlay of the matching isotype control for the appropriate antibody. Percentage numbers shown in histogram boxes indicate positive cells for the appropriate marker. (B) The bar graphs show the mean (± SEM) percentage positive cells for three separate experiments. (C) In a separate set of experiments, the cells were labeled with anti-CD4 Pacific Blue and anti-CD25 PC5, fixed and permeabilized and than intracellulary labeled with FITC-conjugated FOXP3 and PE-conjugated RORγt in parallel with matching isotype controls and subjected to four color analysis by FACSAria sorter. CD4+ T cells were segregated into three populations of CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low, and CD4+CD25+high, isolated by gating and analyzed to determine the percentage of dual expressing FOXP3 and RORγt T cells. Numbers in quadrants of the dot plot indicate the percentage of positive cells for the appropriate marker. Dot plots represent similar results obtained from two separate experiments. (D) In a set of three separate experiments, CD4+CD25+high fraction was segregated following coculture with autologous rF-PANVAC-DCs and stained with PE-conjugated FOXP3 and FITC-conjugated IL-17 antibodies. A representative contour plot is depicted showing single FOXP3 and IL-17 with the appropriate IgGs and a dual color stain depicting the presence of dual FOXP3 and IL-17 positive cells.

(* p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.05).

RORγt transcription is critical for Th17 cell development and function (40–41). While, RORγt transcription factor was expressed in the CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25+low and CD4+CD25+high populations, the level of expression was highest (MFI) in the CD4+CD25+high T cells (Figure 8A and 8B). IL-17A and FOXP3 were strongly co-expressed in CD4+CD25+high T cells (Figure 8A and 8B). The transcription factors, FOXP3 and RORγt, were coexpressed most consistently in the CD4+CD25+high T cells (81%) as compared to 39% of the CD4+CD25+low and 14.3% of CD4+CD25− cells (Figure 8C). Consistent with these findings 66% (SEM ± 3.43; n=3) of the CD4+CD25+high T cells was found to co-express FOXP3 and IL-17 on multichannel flow cytometric analysis (Figure 8D). These observations show that the resultant population of CD4+CD25+high T cells induced by PANVAC transduced DCs express very high levels of pSTAT3, pSTAT6, and FOXP3 consistent with Tregs. However, these cells also exhibit properties of pro-inflammatory cells including high levels of expression of RORγt, IL-17, and IFNγ suggesting that these cells may represent a transition state prior to full commitment to effector cell population (42).

Discussion

Vaccination with attenuated pox viruses bearing tumor associated transgenes has been shown to stimulate anti-tumor immunity in pre-clinical studies (43). Insertion of TRICOM results in enhanced responses and increased capacity to stimulate memory T cell responses, thereby augmenting anti-tumor immunity (44). A prime and boost strategy using vaccinia and fowl pox vectors optimizes T cell responses. In several animal models, vaccination results in prevention of tumor formation and regression of established disease (45).

In clinical studies, pox based anti-tumor vaccines have been shown to induce antigen specific immunity in a subset of patients. In a large study of patients undergoing vaccination with rV-CEA/TRICOM followed by rF-CEA/TRICOM, the development of CEA specific T cell responses, but not T cell immunity directed against irrelevant antigens correlated with improved survival (3). In another study, 25 patients with advanced epithelial tumors underwent vaccination with rV-PANVAC followed by serial boosting with rF-PANVAC (46). Antigen specific responses were observed in 9 of 16 evaluable patients and 2 patients demonstrated evidence of disease regression. However, the relationship between vaccine induced expansion of antigen specific T cells and clinical response has not been fully elucidated. In the present study, we sought to define the nature of the interaction of between PANVAC transduced antigen presenting cells and T cells with regard to the expansion of stimulatory and inhibitory T cell populations and the activation of critical pathways to mediate anti-tumor immunologic responses.

We demonstrated that rF-PANVAC-DCs express high levels of CEA, MUC1, costimulatory and adhesion molecules encoded by the TRICOM genes. These results were in keeping with previous reports which demonstrated that transduction of DCs with vaccinia or fowl pox based vectors expressing CEA, MUC1, and the TRICOM molecules resulted in the expression of all of the introduced genes (1). Signaling via Jak2/STAT3 pathways has been shown to be critically important for normaldendritic cell (DC) differentiation (27). Hyperactivation of the Jak2/STAT3 pathway may be responsible for abnormal DC differentiation in cancer patients, while the use of selective inhibitors promotes maturation and differentiation of mature DCs (21, 27). In the present study, rF-PANVAC transduced DCs demonstrated a decrease in phosphorylated STAT3, and an increase in Tyk2 and phosphorylated STAT1, consistent with normal differentiation and function of the transduced DC populations (19, 47). While, TLR7/8 (and TLR9) have been shown to signal through a MyD88-dependent pathway, leading to the activation of NF-κB and IRF-7 and the production of proinflammatory cytokines (48), stimulation with TLR7/8 had no effect on the levels of STAT and Tyk2 signaling proteins suggesting activation of alternative signaling pathways.

rF-PANVAC-DCs strongly stimulated antigen specific immunity as manifested by the expansion of T cells binding the MUC1 tetramer. An increase in CD8+ T cell expression of perforin and granzyme B was observed, consistent with the acquisition of cytolytic capacity. Stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs also resulted in the expansion of CD4+ T helper cells with an activated phenotype. Moreover, we observed an increase in CD4+CD25+ T cells that expressed Th1 cytokines including IFNγ, IL-2, and TNFα.

A potential concern is that cancer vaccines also induce the expansion of Tregs that blunt their capacity to stimulate effective anti-tumor immunity (49). In contrast, depletion of Tregs has resulted in the enhancement of vaccine efficacy in animal models and clinical studies (50). In the present study, stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs resulted the expansion of CD4+CD25+high T cells that express FOXP3 in the absence of CD127 and suppress T cell responses to primary stimulation. These cells also expressed high levels of CCR7, CCR4, and CD62L suggesting a capacity to migrate to areas of primary T cell activation in the lymph nodes (51–52). The CD4+CD25+high cells exhibited a Th2 phenotype characterized by the expression of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13. IL-13 directly activates the CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells to produce TFG-β which acts directly on CD8+ T cells to down-regulate tumor-specific CTL induction (53). IL-13 upregulates B7-DC (PDL-2) expression, a recently discovered member of the B7 family that binds to PD-1 any may play a role in tumor mediated tolerance (54). The presence of high levels of endogenous IL-13 in the CD4+CD25+highFOXP3+ T cells suggests that these cells may play a major role in this immunosuppressive property by directly downregulating the induction of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. Stimulated CD4+CD25+high T cells also expressed high levels of MCP-1, a CC chemokine shown to display immunoregulatory functions by modulating the differentiation of monocytes and inhibiting Th1 development by down regulating IL-12 production by DCs (36).

Consistent with the expansion of Th2 cells, we demonstrated that stimulation with rF-PANVAC-DCs induces high expression levels of pSTAT6 in the CD4+CD25+highFOXP3+ T cells. STAT6 is upregulated by exposure to IL-4 and IL-13 and plays a key role in Th2 polarization of the immune system (55). Upon IL-4/IL-13 binding to the receptor complex, STAT6 becomes phosphorylated by receptor-associated Janus kinases(JAKs) (55–56). The STAT6 pathway has also been directly implicated in the development and survival of antigen specific CD4+CD25+highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells (39). Levels of phosphorylated STAT3 was also significantly increased in the stimulated CD4+CD25+high T cells. STAT3 activation in tumor cells and tumor-associated inflammatory cells is thought to play a critical role in tumor progression by augmenting tumor survival and tumor angiogenesis and suppressing anti-tumor immunity (37). STAT3 activity in T cells supports the expression of IL-10, TGFβ and FOXP3 all of which are mediators of tumor induced expansion of regulatory T cells (37–38). High levels of MUC1 mRNA expression were observed in the CD4+CD25+high fraction of T cells. While the exact role of MUC1 in modulating immune responsiveness has not been fully elucidated, it effect on cell adhesion, trafficking and cell proliferation and apopotsis support the hypothesis that MUC1 expression on T cells may play an important homeostatic function (34).

rF-PANVAC-DCs stimulated CD4+CD25+high T cells also expressed increased levels of the Th1 cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNFα and the Th17 associated IL-17A and RORγt transcription factors (57). This ambiguous phenotype may reflect an early induction state of effector T cells that may exhibit plasticity dependent on microenvironment factors. The identification of IL-17 producing FOXP3+ Tregs in both mice and humans suggests that Th17 and FOXP3+ regulatory T cell lineages are related in ontogeny. Of note, both lineages depend on TGF-β for their differentiation and/or maintenance (58). Our studies demonstrate that the stimulated CD4+CD25+high T cells expressed high levels of RORγt and IL-17. Recent studies have shown that IL-17 may enhance tumor growth by directly acting on tumor cells and tumor associated stromal cells which bear IL-17 receptors (59).

In summary, we have demonstrated that rF-PANVAC transduced DCs stimulate the expansion of suppressor cell populations with the capacity to inhibit primary DC mediated stimulation of antigen specific responses by a collection of inhibitory mechanisms. Vaccine induced expansion of suppressor cell populations may therefore also inhibit the capacity to generate more consistent clinical responses. However, these cells exhibit a complex phenotype with coexpression of inhibitory and pro-inflammatory cytokines. As such, strategies to augment polarization of T cells towards an activated phenotype and deplete the presence of suppressor cells may result in improved clinical efficacy of the PANVAC transduced DCs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Ovarian Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Grant P50CA105009-04

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tsang KY, Palena C, Yokokawa J, et al. Analyses of recombinant vaccinia and fowlpox vaccine vectors expressing transgenes for two human tumor antigens and three human costimulatory molecules. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1597–1607. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kass E, Schlom J, Thompson J, et al. Induction of protective host immunity to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a self-antigen in CEA transgenic mice, by immunizing with a recombinant vaccinia-CEA virus. Cancer Res. 1999;59:676–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall JL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, et al. Phase I study of sequential vaccinations with fowlpox-CEA(6D)-TRICOM alone and sequentially with vaccinia-CEA(6D)-TRICOM, with and without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, in patients with carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:720–731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo-Saito C, Hodge JW, Kwak H, et al. 4-1BB ligand enhances tumor-specific immunity of poxvirus vaccines. Vaccine. 2006;24:4975–4986. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman HL, Kim-Schulze S, Manson K, et al. Poxvirus-based vaccine therapy for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Transl Med. 2007;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pantuck AJ, van Ophoven A, Gitlitz BJ, et al. Phase I trial of antigen-specific gene therapy using a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding MUC-1 and IL-2 in MUC-1-positive patients with advanced prostate cancer. J Immunother. 2004;27:240–253. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smits EL, Ponsaerts P, Berneman ZN, et al. The use of TLR7 and TLR8 ligands for the enhancement of cancer immunotherapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:859–875. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito K, Ait-Goughoulte M, Truscott SM, et al. Hepatitis C virus inhibits cell surface expression of HLA-DR, prevents dendritic cell maturation, and induces interleukin-10 production. J Virol. 2008;82:3320–3328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02547-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito T, Amakawa R, Kaisho T, et al. Interferon-alpha and interleukin-12 are induced differentially by Toll-like receptor 7 ligands in human blood dendritic cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1507–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amsen D, Spilianakis CG, Flavell RA. How are T(H)1 and T(H)2 effector cells made? Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egwuagu CE, Yu CR, Zhang M, et al. Suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins are differentially expressed in Th1 and Th2 cells: implications for Th cell lineage commitment and maintenance. J Immunol. 2002;168:3181–3187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cote AL, Usherwood EJ, Turk MJ. Tumor-specific T-cell memory: clearing the regulatory T-cell hurdle. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1614–1617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, et al. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalinski P, Urban J, Narang R, et al. Dendritic cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines: what we have and what we need. Future Oncol. 2009;5:379–90. doi: 10.2217/FON.09.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson SH, Yu CR, Mahdi RM, et al. Dendritic cell maturation requires STAT1 and is under feedback regulation by suppressors of cytokine signaling. J Immunol. 2004;172:2307–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokumasa N, Suto A, Kagami S, et al. Expression of Tyk2 in dendritic cells is required for IL-12, IL-23, and IFN-gamma production and the induction of Th1 cell differentiation. Blood. 2007;110:553–560. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-059246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Wang T, et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:1314–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:941–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voo KS, Wang YH, Santori FR, et al. Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4793–4798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad R, Raina D, Meyer C, et al. Triterpenoid CDDO-methyl ester inhibits the Janus-activated kinase-1 (JAK1)-->signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) pathway by direct inhibition of JAK1 and STAT3. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2920–2926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasir B, Wu Z, Crawford K, et al. Fusions of dendritic cells with breast carcinoma stimulate the expansion of regulatory T cells while concomitant exposure to IL-12, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides, and anti-CD3/CD28 promotes the expansion of activated tumor reactive cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:808–821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsang KY, Zhu M, Even J, et al. The infection of human dendritic cells with recombinant avipox vectors expressing a costimulatory molecule transgene (CD80) to enhance the activation of antigen-specific cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7568–7576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brossart P, Heinrich KS, Stuhler G, et al. Identification of HLA-A2-restricted T-cell epitopes derived from the MUC1 tumor antigen for broadly applicable vaccine therapies. Blood. 1999;93:4309–4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nefedova Y, Cheng P, Gilkes D, et al. Activation of dendritic cells via inhibition of Jak2/STAT3 signaling. J Immunol. 2005;175:4338–4346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay CR, et al. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:875–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baatar D, Olkhanud P, Newton D, et al. CCR4-expressing T cell tumors can be specifically controlled via delivery of toxins to chemokine receptors. J Immunol. 2007;179:1996–2004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebastiani S, Allavena P, Albanesi C, et al. Chemokine receptor expression and function in CD4+ T lymphocytes with regulatory activity. J Immunol. 2001;166:996–1002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iellem A, Mariani M, Lang R, et al. Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:847–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1693–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Q, Munger ME, Highfill SL, et al. Program death-1 signaling and regulatory T cells collaborate to resist the function of adoptively transferred cytotoxic T lymphocytes in advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2484–2493. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agrawal B, Longenecker BM. MUC1 mucin-mediated regulation of human T cells. Int Immunol. 2005;17:391–399. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasir B, Avigan D, Wu Z, et al. Dendritic cells induce MUC1 expression and polarization on human T cells by an IL-7-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174:2376–2386. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omata N, Yasutomi M, Yamada A, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 selectively inhibits the acquisition of CD40 ligand-dependent IL-12-producing capacity of monocyte-derived dendritic cells and modulates Th1 immune response. J Immunol. 2002;169:4861–4866. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kortylewski M, Yu H. Role of Stat3 in suppressing anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez-Guajardo V, Tanchot C, O’Malley JT, et al. Agonist-driven development of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells requires a second signal mediated by Stat6. J Immunol. 2007;178:7550–7556. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ivanov, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng T, Cao AT, Weaver CT, et al. Interleukin-12 converts Foxp3+ regulatory T cells to interferon-gamma-producing Foxp3+ T cells that inhibit colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:2031–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitz J, Reali E, Hodge JW, et al. Identification of an interferon-gamma-inducible carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) CD8(+) T-cell epitope, which mediates tumor killing in CEA transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5058–5064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang S, Tsang KY, Schlom J. Induction of higher-avidity human CTLs by vector-mediated enhanced costimulation of antigen-presenting cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5603–5615. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hance KW, Zeytin HE, Greiner JW. Mouse models expressing human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as a transgene: evaluation of CEA-based cancer vaccines. Mutat Res. 2005;576:132–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eder JP, Kantoff PW, Roper K, et al. A phase I trial of a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing prostate-specific antigen in advanced prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1632–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pilz A, Kratky W, Stockinger S, et al. Dendritic cells require STAT-1 phosphorylated at its transactivating domain for the induction of peptide-specific CTL. J Immunol. 2009;183:2286–2293. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR, et al. The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:210–29. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews DM, Maraskovsky E, Smyth MJ. Cancer vaccines for established cancer: how to make them better? Immunol Rev. 2008;222:242–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, et al. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneider MA, Meingassner JG, Lipp M, et al. CCR7 is required for the in vivo function of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:735–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan Q, Bromley SK, Means TK, et al. CCR4-dependent regulatory T cell function in inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1327–1334. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1741–1752. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsumoto K, Fukuyama S, Eguchi-Tsuda M, et al. B7-DC induced by IL-13 works as a feedback regulator in the effector phase of allergic asthma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heller NM, Matsukura S, Georas SN, et al. Interferon-gamma inhibits STAT6 signal transduction and gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:573–582. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0195OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hebenstreit D, Wirnsberger G, Horejs-Hoeck J, et al. Signaling mechanisms, interaction partners, and target genes of STAT6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:173–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimura A, Naka T, Kishimoto T. IL-6-dependent and -independent pathways in the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12099–12104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang L, Yi T, Kortylewski M, et al. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1457–1464. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]