Abstract

Amoebic liver abscess (ALA) is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication of infection with the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica. E histolytica is widely distributed throughout the tropics and subtropics, causing up to 40 million infections annually. The parasite is transmitted via the fecal-oral route, and once it establishes itself in the colon, it has the propensity to invade the mucosa, leading to ulceration and colitis, and to disseminate to distant extraintestinal sites, the most common of which is the liver. The authors provide a topical review of ALA and summarize clinical data from a series of 29 patients with ALA presenting to seven hospitals in Toronto, Ontario, a nonendemic setting, over 30 years.

Keywords: Amoebiasis, Entamoeba histolytica, Liver abscess

Abstract

L’abcès amibien du foie (AAF) est une complication peu courante de l’infection au parasite protozoaire Entamoeba histolytica qui peut mettre en jeu le pronostic vital. Le E histolytica est largement répandu dans les tropiques et les subtropiques et peut causer jusqu’à 40 millions d’infections chaque année. Le parasite est transmis par voie orofécale et, une fois établi dans le côlon, il a la propension d’envahir la muqueuse, entraînant une ulcération et une colite, et de se disséminer dans des foyers extra-intestinaux éloignés, dont le plus courant est le foie. Les auteurs proposent une analyse actuelle de l’AAF et résument les données cliniques d’une série de 29 patients ayant un AAF qui ont consulté dans sept hôpitaux de Toronto, en Ontario, un milieu non endémique, sur une période de 30 ans.

The MEDLINE database and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched for articles published between 1983 and 2010. The Cochrane search yielded one relevant article. In the MEDLINE search, the following medical subject headings terms were used: “parasitic liver disease”, “amoebiasis”, “amoebic liver abscess” and “liver abscess”. Case reports were not included in the data synthesis. The search was limited to systematic reviews and the most recent randomized trials conducted in English. All of the abstracts of identified articles were examined for relevance. Retrieved studies were screened for duplication, and additional studies were identified using a manual search of the reference lists of the relevant included articles. Additional references (n=2) were included by contacting clinical experts. Few randomized controlled trials have been conducted; therefore, most recommendations are based on data from retrospective cohorts, case series and expert opinion, unless otherwise stated.

To add local Canadian experience to the published data, we have included a review of retrospective demographic and clinical data from 29 patients who presented to seven Toronto (Ontario) hospitals between 1980 and 2005.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Amoebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the intestinal protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. Globally, it is estimated that 40 million people are infected annually (1,2), although these estimates are confounded by inclusion of the morphologically identical but nonpathogenic species Entamoeba dispar (3). E dispar, also transmitted via the fecal-oral route, is 10 times more likely to cause asymptomatic carriage than E histolytica. E histolytica disease results in 40,000 to 100,000 deaths each year from amoebic colitis and extraintestinal infection (4,5). Amoebic liver abscesses (ALA) are the most common extraintestinal site of infection, and occur in fewer than 1% of E histolytica infections (5,6).

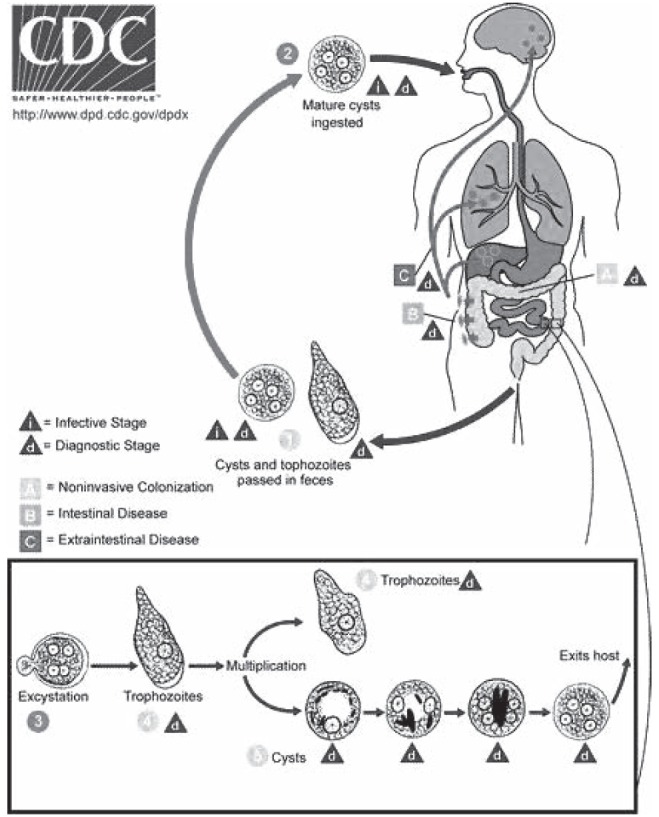

E histolytica infection occurs when mature cysts are ingested, typically through fecally contaminated water or food, most frequently in the developing world. When the parasite reaches the small intestine, excystation occurs, releasing trophozoites (the ‘feeding stage’ of the parasite [Figure 1]), which then penetrate the colonic mucosa. There they can cause flask-shaped colonic ulcerations and gain access to the portal venous system to infect the liver, brain, lungs, pericardium and other metastatic sites. In the liver, the amoebae generate an inflammatory reaction and cause necrosis of hepatocytes, producing an abscess. Interestingly, there is a relative paucity of inflammatory cells from biopsy specimens, which is believed to be due to lysis of cells by E histolytica (7).

Figure 1).

Life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica. Cysts and trophozoites are passed in feces (1). Cysts are typically found in formed stool, whereas trophozoites are typically found in diarrheal stool. Infection by E histolytica occurs by ingestion of mature cysts (2) in fecally contaminated food, water or hands. Excystation (3) occurs in the small intestine and trophozoites (4) are released, which migrate to the large intestine. The trophozoites multiply by binary fission and produce cysts (5), and both stages are passed in the feces (1). Because of the protection conferred by their walls, the cysts can survive days to weeks in the external environment and are responsible for transmission. Trophozoites passed in the stool are rapidly destroyed once outside the body, and if ingested would not survive exposure to the gastric environment. In many cases, the trophozoites remain confined to the intestinal lumen (A noninvasive infection) of individuals who are asymptomatic carriers, passing cysts in their stool. In some patients the trophozoites invade the intestinal mucosa (B intestinal disease), or, through the bloodstream, extraintestinal sites such as the liver, brain and lungs (C extraintestinal disease), with resultant pathological manifestations. Transmission can also occur through exposure to fecal matter during sexual contact (in which case not only cysts, but also trophozoites could prove infective). Content source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (www.cdc.gov/parasites/amebiasis/biology.html), accessed October 31, 2010

Most cases of invasive amoebiasis in developed countries, such as Canada, occur in immigrants from E histolytica-endemic countries, but infection in short-term travellers is also possible. Knobloch and Manweiler (6) found that 35% of travellers spent fewer than six weeks in an endemic area before developing ALA. Mexico, Central and South America, India and Africa are the most highly endemic regions (5). In addition to travel to an endemic region, other risk factors for acquisition include men who have sex with men and institutionalization. Heterosexual transmission of ALA has also recently been described (8). Suppression of cell-mediated immunity increases the risk of invasive disease, such as through corticosteroids, malignancy, extremes of age and pregnancy (9).

Previously unpublished epidemiological data from our 29 patients reflect the typical clinical presentation of ALA in returning travellers that is reported in the literature. In our cohort, the median age was 33 years; 83% were male (Box 1). Nineteen patients were foreign born, and 86% had travelled to the tropics before presentation. The median time between travel and presentation was 28 weeks, with a broad range of one day to 14 years. Forty per cent had travelled to Southeast Asia and the remainder had travelled to various locations in the tropics.

BOX 1. Characteristics of 29 patients presenting to seven hospitals in Toronto, Ontario, between 1980 and 2005.

| Age, years, median (range) | 33 (22–54) |

| Male sex | 24 (83) |

| History of travel to the tropics | 25 (86) |

| Time between travel and symptom onset, median (range) | 28 weeks (1 day to 14 years) |

| Duration of symptoms before diagnosis, days, median (range) | 14 (2–271) |

| Region of travel | |

| South Asia | 10 (40) |

| North Africa or Middle East | 3 (12) |

| South America | 3 (12) |

| Central America or Carribean | 3 (12) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3 (12) |

| Southeast Asia | 1 (4) |

| Pacific Islands | 1 (4) |

| Symptoms at presentation | |

| Fever | 26 (90) |

| Anorexia | 19 (66) |

| Abdominal pain | 16 (55) |

| Weight loss | 14 (48) |

| Right chest pain | 12 (41) |

| Diarrhea or dysentery | 11 (38) |

| Signs at presentation | |

| Fever | 23 (79) |

| Right upper quadrant tenderness | 22 (76) |

| Epigastric tenderness | 15 (52) |

| Right basilar lung signs | 8 (28) |

| Icterus | 7 (24) |

| Diagnostics | |

| Stool trophozoite seen | 7 (24) |

| Serology positive | 27 (93) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

ALA is 10 times more common in adult males than females (10). The distribution of colonic infection (symptomatic and asymptomatic) is nearly identical between males and females, suggesting a male-related susceptibility for invasive disease. Proposed factors contributing to this sex disparity include alcoholic hepatocellular damage in males, and the protective effect of relative iron deficient anemia or protective hormonal factors in women of child-bearing age (11,12). However, the definitive explanation as to why adult males are more susceptible to invasive disease remains elusive. Other risk factors for invasive amoebiasis, including ALA, are summarized in Box 2.

BOX 2. Risk factors for invasive amoebiasis.

| Host | Agent | Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Malnutrition | Pathogenic strains of Entamoeba histolytica with greater capacity for contact-dependent cytolysis, phagocytosis, proteolysis | Overcrowding |

| Vitamin deficiencies | Poor sanitation | |

| Alcoholism | Low socioeconomic status | |

| Immune suppression due to HIV/AIDS, malignancy, corticosteroid use, neonate status, pregnancy | ||

| Institutional living | ||

| Travel to an endemic region |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

ALA commonly presents with an acute or subacute history of fever and right upper quadrant pain, although in 20% to 50% of cases, a more chronic presentation occurs with a protracted history of diarrhea, weight loss and abdominal pain (3). The median duration of symptoms before presentation was 14 days in our series of patients (clinical presentations are summarized in Box 1). Of note, a history of diarrhea or dysentery was present in 38% of patients; again, consistent with previously reported literature (13). Nevertheless, 50% of patients have been found to exhibit colonic ulceration on colonoscopy with presentation, suggesting a possible portal of entry. Jaundice or icterus is uncommon, occurring in 24% of patients; when present, it may suggest more severe disease such as multiple abscesses (11).

Complications of ALA involve rupture of the abscess causing spread into the peritoneum, pleural space or pericardium. Rupture into the pleuropulmonary system occurs in up to 40% of patients with ALA, while peritoneal rupture occurs in only 7% of patients (14). In our patient population, extension of the abscess into the chest cavity occurred in six individuals. Obstructive jaundice, inferior vena cava obstruction and bacterial superinfection have also been described (15). Rarely, extraintestinal abscesses can also occur via hematogenous spread to the brain, lung, spleen, vagina, uterus and skin.

DIAGNOSIS

Supportive diagnostic features of ALA include an elevated white blood cell count occurring in 75% of patients; eosinophilia is not a feature (16). Liver transaminase levels may be elevated in up to two-thirds of patients, whereas alkaline phosphatase levels are more likely to be elevated, especially in patients with more indolent disease. Anemia is present in more than one-half of cases and hyperbilirubinemia in one-third. Compared with pyogenic abscess, hypoalbuminemia is more common in ALA (17), occurring in up to two-thirds of ALA patients in our reviewed cases. Other compatible features include elevation of the right hemidiaphragm on chest x-ray, which occurs in one-third of cases at presentation.

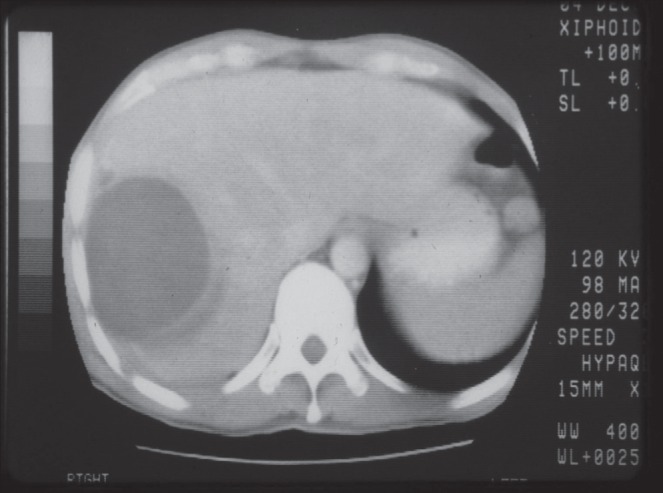

Ultrasonography has previously been reported to have a sensitivity of more than 90% for imaging ALAs (18) and, if available, is a reasonable initial test. A recent retrospective case series (19) found a much lower sensitivity (58%); however, because the accuracy of ultrasonography is operator dependent, this may have accounted for the low sensitivity in this study. Nevertheless, if clinical suspicion is high and the initial ultrasound is reported to be negative, a computed tomography scan is recommended. Compared with pyogenic abscesses, ALAs are more commonly solitary and more likely to involve the right lobe of the liver (Figure 2). However, the presence of multiple abscesses in the liver does not rule out ALA (17). ALAs can vary in size; we found a median diameter of 8 cm, with a ranging of 4 cm to 12 cm.

Figure 2).

Noncontrast computed tomography image demonstrating right-sided amoebic liver abscess in a patient presenting to care in Toronto, Ontario, after international travel. The abscess is homogenous and single, which is a typical finding

In the appropriate clinical setting, a reliable diagnosis can often be made serologically. Strong serum antibody response will develop with infection due to E histolytica but not usually with E dispar infection of the bowel, which, if present, usually elicits a weak response (20). The absence of antibody to E histolytica after one week of symptoms argues strongly against the diagnosis of ALA or invasive bowel disease: serum antibodies are detected in 85% to 95% of patients with ALA after one or more week(s) of symptoms. These antibodies may persist after the acute infection, although this issue is less likely to be a confounding factor in a nonendemic area such as Canada (21).

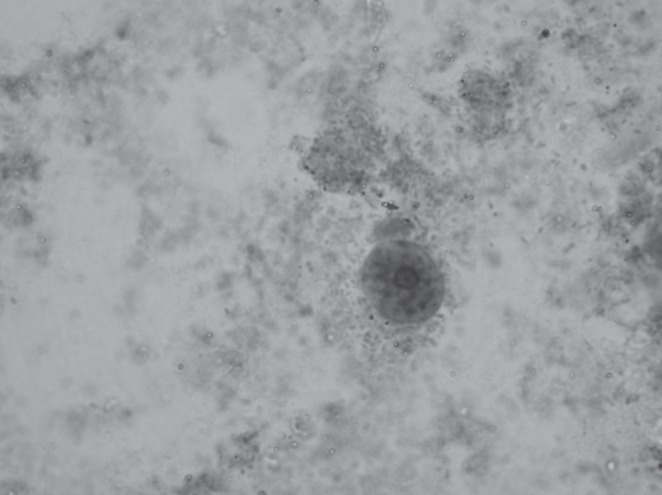

E histolytica cysts or trophozoites in the stool are neither sensitive nor specific but were present in 24% of our series. Furthermore, their presence in the stool may be confused with asymptomatic carriage, particularly of E dispar (3). The two cannot be distinguished by stool microscopy (Figure 3) unless red blood cell inclusions are visualized. The two species can be differentiated by fresh stool antigen testing, which detects the E histolytica Gal/GalNAc adherence lectin, and by serology (3,22,23). Finally, isolation and microscopic demonstration from aspirates of ALAs is possible (24) if the diagnosis is uncertain. If an ALA is aspirated, the classic description of the thick fluid yielded is one of ‘anchovy paste’; however, other colours are also common.

Figure 3).

Entamoeba histolytica cyst (trichrome stain, original magnification ×1000) found in the stool of a patient with amoebic liver abscess. The cysts show a small, centrally located karyosome and regular peripheral chromatin within their nuclei. The cysts are not distinguishable morphologically from Entamoeba dispar

The main differential diagnosis to consider is pyogenic liver abscess, which is more common overall than ALA in nonendemic settings (25). Pyogenic abscesses, unlike ALAs, have no sex bias, are more likely to be multiple, occur in older individuals with underlying hepatobiliary comorbidities, and are generally associated with positive blood or aspirate bacterial cultures (see Box 3 for further comparison). However, Klebsiella pneumoniae, the number one cause of pyogenic liver abscesses in recent reviews, are most commonly not loculated (25). Furthermore, a syndrome of pyogenic liver abscess caused by hypermucoviscous K pneumoniae (most often due to capsular serotype K1) has recently emerged; it is often associated with metastatic ocular or cerebral infection, and is most commonly seen in patients of Asian descent (26). Other diagnoses to consider include hepatocellular carcinoma and cystic echinococcosis (hydatid). Initial misdiagnosis was common in our patient review, with admission diagnoses of subphrenic abscess (10%), hepatitis (10%), cholecystitis (7%) and abdominal pain not yet diagnosed (7%) the most well represented alternative diagnoses among inpatients with ALA.

BOX 3. Comparison of epidemiological and clinical features of pyogenic and amoebic liver abscesses.

| Feature | Pyogenic abscess | Amoebic liver abscess |

|---|---|---|

| Sex bias | No | Males |

| Typical age at presentation | Fifth to seventh decade of life | Third decade of life |

| History of tropical travel | Uncommon | Almost universal |

| Underlying hepatobiliary comorbidities | Very common | Uncommon |

| Number of abscesses | Often small and multiple | Usually single; right lobe |

| Hypoalbuminemia | Uncommon | Common |

| Positive blood or aspirate bacterial cultures | Common | Rare |

| Elevation of the right hemidiaphragm on chest x-ray | Uncommon | Common |

| Amoebic serology | Negative | Positive in 90% within 2 weeks of symptom onset |

TREATMENT

Nitroimidazoles, mainly metronidazole, have been the standard of treatment for ALA for more than 40 years and remain the treatment of choice. Metronidazole is given in an oral dose of 750 mg three times daily for seven to 10 days (Table 1) although case series have demonstrated the potential efficacy of a single dose of 2.5 g (27). Side effects including gastrointestinal upset and metallic taste are common, and patients must be cautioned against the disulfiram-like reaction with alcohol use. Following treatment of invasive amoebiasis, 40% to 60% of patients will continue to harbour intracolonic cysts. Thus, it is essential to follow treatment of invasive disease with a lumen-active agent, such as iodoquinol, with an oral dose of 650 mg three times daily for 20 days or paromomycin in an oral dose of 25 mg/kg/day to 35 mg/kg/day in three divided doses for seven days (28).

TABLE 1.

Current treatment recommendations for amoebic liver abscess (ALA)

| Treatment phase* | Drug |

Dose

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Pediatric | ||

| Initial treatment of ALA | Metronidazole | 750 mg PO TID × 7–10 days | 35–50 mg/kg/day DIVIDED TID × 7–10 days |

| Tinidazole (not available in Canada) | 2 g once PO daily × 3 days | >3 years: 50 mg/kg/day (max 2 g) PO in 1 dose × 3 days | |

| Clearance of luminal cysts | Iodoquinol | 650 mg PO TID × 20 days | 30–40 mg/kg/day DIVIDED TID × 20 days (max 2 g/day) |

| Paromomycin | 500 mg PO TID × 7 days OR 25–35 mg/kg/day DIVIDED TID × 7 days |

25–35 mg/kg/day DIVIDED TID × 7 days | |

Select one drug for the initial phase of treatment, which should then be followed by a second drug for clearance of cysts. max Maximum; PO Per oral; TID Three times daily

A Cochrane Review from 2009 concluded that there has been no demonstrable advantage of percutaneous drainage of an uncomplicated abscess due to E histolytica compared with treatment with metronidazole alone (11,29). Cure rates of more than 90% have been reported with medical therapy, with resolution of fever, pain and anorexia within 72 h to 96 h (30,31). Diagnostic uncertainty with a pyogenic abscess, such as absence of clinical response or worsening pain, tenderness and jaundice, or abscesses judged to have a high risk for peritoneal or pericardial rupture (located in left liver lobe or >10 cm), should be considered indications for drainage (3,32).

PREVENTION

Because E histolytica has a fecal-oral route of transmission, similar to many pathogens encountered in developing-world settings, travellers can reduce the risk of acquiring E histolytica by adherence to safe food, water and hand hygiene practices while abroad. While an oral vaccine that stimulates cellular and mucosal immunity has the potential to contribute to the global control of amoebiasis and ALA, presently, putative vaccine candidates are only being tested in animal models.

Additional reading and resource material on ALA can be found at <www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/amebiasis/default.htm>.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ellen L, Stanley SL. Amebiasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:417–92. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. WHO/PAHO/UNESCO. Consultation of experts on amoebiasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1997;72:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aucott JN, Ravdin JI. Amebiasis and “nonpathogenic” intestinal protozoa. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7:467–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kain KC, Boggild AK. Amebiasis. In: Rakel RE, Bope ET, editors. Conn’s Current Therapy. 56th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2004. pp. 60–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haque R, Huston C, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri W. Amebiasis. N Eng J Med. 2003;348:1565–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knobloch J, Manweiler E. Development and persistence of antibodies to Entamoeba histolytica in patients with amebic liver abscess: Analysis of 216 cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:727–32. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa-Cantellano M, Martínez-Palomo A. Pathogenesis of intestinal amebiasis: From molecules to disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:318–31. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.318-331.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salit IE, Khairnar K, Gough K, Pillai DR. A possible cluster of sexually transmitted Entamoeba histolytica: Genetic analysis of a highly virulent strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:346–53. doi: 10.1086/600298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salanta RA, Martinez-Palomo A, Murray HW, et al. Patients treated for amebic liver abscess develop cell mediated immune responses effective in vitro against Entamoeba histolytica. J Immunol. 1986;136:2633–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maltz G, Knauer CM. Amebic liver abscess: A 15 year experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanley SL., Jr Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scragg JN. Hepatic amebiasis. Semin Liver Dis. 1984;4:277–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misra SP, Misra V, Dwivedi M. Factors influencing colonic involvement in patients with amebic liver abscess. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:512–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02877-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li E, Stanley SL., Jr Parasitic diseases of the liver and intestines. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:471–92. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao S, Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Petri W. Hepatic amebiasis: A reminder of the complications. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:145–9. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32831ef249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed SL. Amebiasis: An update. Clin Inf Dis. 1992;14:385–91. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodhi S, Sarwari AR, Muzammil M, Salam A, Smego RA. Features distinguishing amoebic from pyogenic liver abscess: A review of 577 adult cases. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:718–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura K, Stoopen M, Reeder MM, Moncada R. Amebiasis: Modern diagnostic imaging with pathological and clinical correlation. Semin Roent. 1997;4:250–75. doi: 10.1016/s0037-198x(97)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elzi L, Laifer G, Sendi P, Ledermann HP, Fluckiger U, Bassetti S. Low sensitivity of ultrasonography for the early diagnosis of amebic liver abscess. Am J Med. 2004;117:519–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson TF. Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar are distinct species; clinical, epidemiological and serological evidence. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:181–6. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma MP, Ahuja V. Amoebic liver abscess. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2003;4:107–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SY, Sun HY, Ji DD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of detection of intestinal amebiasis by using serology and specific-amebic-antigen assays among persons with or without human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Micro. 2008;46:3077–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01151-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pillai DR, Keystone JS, Sheppard DC, MacLean JD, MacPherson DW, Kain KC. Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar: Epidemiology and comparison of diagnostic methods in a setting of nonendemicity. Clin Infec Diseases. 1999;29:1315–8. doi: 10.1086/313433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhambhani S, Kashyap V. Amoebiasis: Diagnosis by aspiration and exfoliative cytology. Cytopath. 2001;12:329–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lederman ER, Crum NF. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: An emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:322–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang C, Lai S, Yi W, 2, Hsueh P, Liu K, Chang S. Klebsiella pneumoniae Genotype K1: An emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:284–93. doi: 10.1086/519262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irusen EM, Jackson TF, Simjee AE. Asymptomatic intestinal colonization by pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica in amebic liver abscess: Prevalence, response to therapy, and pathogenic potential. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:889–93. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.4.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes MA, Petri WA. Amebic liver abscess. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:565–82. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chavez-Tapia NC, Hernandez-Calleros J, Tellez-Avila FI, Torre A, Uribe M. Image-guided percutaneous procedure plus metronidazole versus metronidazole alone for uncomplicated amoebic liver abscess. The Cochrane Library. 2009;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004886.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petri WA, Jr, Singh U. Diagnosis and management of amebiasis. Clin Inf Dis. 1999;29:1117–25. doi: 10.1086/313493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravdin JI. Amoebiasis. Clin Inf Dis. 1995;20:1453–66. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Sonnenberg E, Mueller PR, Schiffman HR. Intrahepatic amebic abscesses: Indications for and results of percutaneous catheter drainage. Radiology. 1985;156:631–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.3.4023220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]